NEWFOUNDLAND (says Mr.

Morris) was a dependency of England, her only colony a century before

Massachusetts, New York or Virginia, emerged from barbarism. When the

‘untutored Indian' uncontrolled by civilized man, roamed through these

now busy marts, redundant with wealth, population, and all the

advantages of civilization, Newfoundland was resorted to by thousands of

British, Spaniards, French and Portuguese; and millions were drawn from

her mines—the fisheries—far more valuable than those of Mexico and

Peru.”

McGregor, in his

British America, says :—

“Newfoundland, although

occupying no distinguished place in the history of the New World, has,

notwithstanding, at least for two centuries and a half after its

discovery by Cabot, in 1497, been of more mighty importance to Great

Britain than any other colony; and it is doubtful if the British Empire

could have risen to its great and superior rank among the nations of the

earth, if any other power had held the possession of Newfoundland; its

fishery having, ever since its commencement, furnished our navy with a

great proportion of its hardy and brave sailors.”

And the first Mr. Pitt,

in declaiming upon the national interests of Great Britain, affirmed

that one point was of such moment, as not to be surrendered, though the

enemy was master of the Tower of London;—the Newfoundland fisheries. The

Europeans first began the fishery on the Newfoundland coast, in 1502.

The Portuguese were the first; and subsequently the Biscayans, and the

French. In 1578, the Portuguese had 50 vessels engaged in the fishery;

the English also 50; and the French and Spanish 150. So important had

this fishery become, that in the year 1(534, France consented to pay a

tribute of Jive per cent, to the British Government, rather than

relinquish the privilege of fishing on the coast; which continued until

the reign of Charles II., a period of forty-one years. In 17(53, France

removed all her -pretensions to Nova Scotia, for the privilege of

fishing on the northern parts of Newfoundland ; from this time the

French fishery rapidly increased. In 1721, France employed 400 .ships in

the Newfoundland fishery. The Grand Bank, or deep sea fishery at one

time, gave employment to 400 British ships, manned by 7,000 men; and

during the last war, 700 ships were employed on the Banks.

This important fishery

is now wholly in the hand of the French and Americans, not a single

British ship is now employed in the fisheries on the Banks of

Newfoundland. Mr. Morris, late Colonial Treasurer of Newfoundland, says:

—“Why do not British ships resort to the Banks as formerly? The reason

is at hand—because under the present unequal and unnatural competition,

nothing but the most certain ruin would be entailed on the British, if

they ventured into the Bank and deep-sea fisheries. The price of fish

reduced far below its intrinsic value, in all the markets of the world,

common to these three nations, by the competition of the French and

Americans, would not pay one-half the outfit. A British merchant fitting

out a ship of 250 or 300 tons for the Bank fishery in the same manner in

which the French fit out their vessels, would, at the present price of

fish, calculate upon a certain loss of $4,000 to $5,000. This cause

operates as the most effectual prohibition.

The French have adopted

a new mode of fishing on the Banks, their vessels anchor, which was not

allowed in former times, they have also adopted what is called the

Bultow system, and which is clearly explained in a memorial presented by

Messrs. Mudge & Co., to the late Governor of Newfoundland, Sir John

Harvey.

“ That the Bultow

system is carried on in the following manner :—The vessel is provided

with two or three large boats, of a size fit to carry out, at

considerable distances, large supplies of rope and line, with moorings

and anchors sufficient to ride at anchor on the open Bank in rough

weather. These boats carry out from five to six thousand fathoms of rope

to which are fastened leads, with baited hooks at certain distances from

each other. These are carried out from the vessels in different

directions and let down and secured with suitable moorings, to prevent

their being carried away by the strong currents that usually prevail on

the Bank. They are then laid out at stated distances from each other,

with several thousand hooks well baited, and frequently occupy several

miles of ground. On the next day they are taken up and overhauled—the

fish taken off, —and, if the berth is approved, the hooks fresh baited

and let down again, and thus successively during the voyage. But should

the berth in which they have anchored not prove a good one, they heave

up and sail about to make another, in doing which, if they chance to see

an English vessel catching fish freely with hook and line, they anchor

near her and lay out their Bultows, which, spreading so large a quantity

of bait, the fish are soon drawn thereby from the few caplin presented

by the English vessel, and the latter is therefore obliged to heave up

and sail away from the good fishing ground, to find a berth elsewhere:

so that not only does the English vessel lose the good fishing in which

she was engaged, but the most valuable part of the season is often lost

in wandering about to find a new berth clear of the French ships; for

they are so numerous, and each covers with its Bultows so large a space,

that it would be difficult to keep clear of them, and any place near

them it is, for the reasons above stated, useless to attempt occcupying;

so that in effect the French have monopolized to themselves all the best

fishing ground.

“Your Memorialists’

vessel fell in with one of these Bultows, which had gone adrift,

measuring 1,500 fathoms.

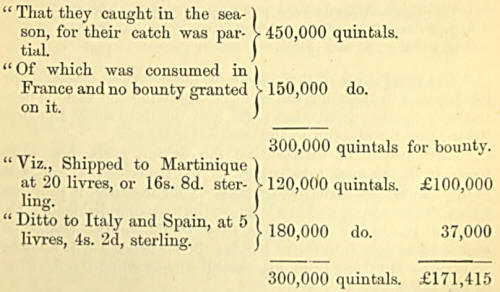

“To show the working of

the French system of bounties in their Newfoundland Fisheries, and to

prove the hopelessness of competition on the part of the British

merchant and fisherman, it is only necessary to exhibit a statement of

the outfit and returns of a French ship of three hundred tons on the

Grand Bank S of Newfoundland, procured by a gentleman who recently

arrived from St. Pierre and Miquelon, and the results of the last

season’s voyage of 1846.

“Vessels of 150 tons

from France are obliged to bring out 30 men and boys, one boy under 15

years of age to every ten men.

“Vessels over 150 tons

are obliged to bring out 50 men and boys.

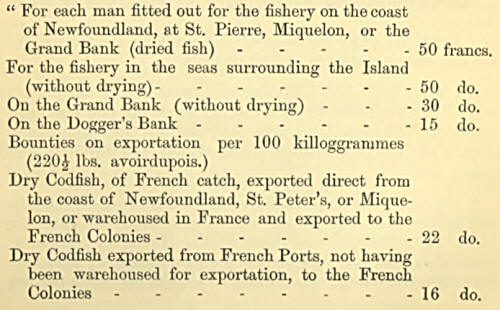

“The bounty on every

man and boy is 50 francs, and on fish 10 francs.

“Boys receive as wages

50 francs for the season. Men receive a portion of the voyage and from

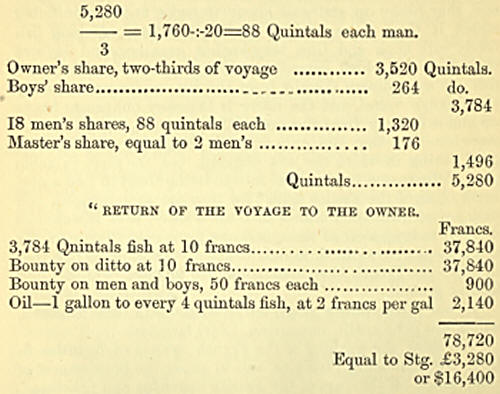

50 to 100 francs each. The voyage is divided by three, two-thirds to the

owners, and one-third to the crew. The master, in addition to his wages,

which vary from 70 to 100 francs per month, receives two men’s share of

fish; for example, one ship in 1846 landed 132,000 fish; equal to 5,280

quintals, with a crew of 18 men.

“According to the

statement, the French merchant obtains in the form of bounty, 10 francs,

say 8s. 4d. sterling, which, with the bounties for the men and boys, and

the drawbacks on the necessaries for the supply of the voyage, raises it

to at least 10s. stg. per quintal. If he obtains 10s. for the fish at

market it will realize 20s. per quintal. Let the case of the British

merchant, who fits out a ship for the Grand Bank, be placed in

juxtaposition; he has to sell his fish in the markets of the world, open

alike to both, the price is regulated for him by the sale of the bounty

fish of the French. He receives 10s;, while the French merchant realizes

20s. Such disparity puts an end to all competition, the Biitish

merchant, as a matter of necessity, has to surrender the Fishery

altogether into the hands of his protected rivals. In the year 1838, the

writer had the honour of an interview with Sir George Grey, at the

Colonial Office. In bringing this subject under his consideration, he

supposed an example of two cloth manufacturers, having warehouses for

the sale of their wares at Cheapside, one had a bounty of 5s. per yard

for every yard of cloth he manufactured, the other no bounty; the

competition could not be maintained without a ruinous sacrifice on the

part of the latter. This is not an inapt simile to show the ruinous

competition which the British in the Newfoundland Fisheries have to

maintain with their foreign and more favoured rivals.”

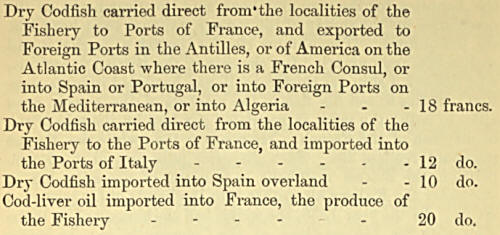

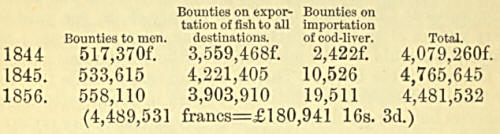

The following Return of

the French bounties was obtained by the British Ambassador at Paris, in

1848 :—

“Total Bounties Paid in

1844, ’45, '46.

“Drawback of all duties

on salt used in the curing of the fish, except 50 centimes (4½d. stg.)

per 100 kilog. on foreign salt imported for the coast of Newfoundland,

St. Pierre and Miquelon fishery.

“Drawback of all duties

on all the outfit for the fishery, including vessels employed and all

utensils.”

In May, 1830, the

Chamber of Commerce of St. John s sent Mr. Sweetland to the French shore

on the northern coast of Newfoundland, who laid before the Chamber a

report of his proceedings, from which the following is taken:—

“The number of ships

employed this season by the French in this fishery were 266 in all,

viz.—From Granville, 116; St. Malo, 110; Paimpol and Bennick, 30; Havre,

4; Nantes, 6. Total 266, from 100 to 350 tons burden, having 51 men and

boys each, amounting in the whole to 13,566, one tenth portion of whom

were boys. This number surpassed considerably the Governor’s estimate, a

very good one, which was assigned to me by the French gentleman from

whom I received the information. Each establishment had two. some four,

cod seines from sixteen to thirty fathoms deep, and 200 fathoms long.

Their caplin seines were from twenty-one feet to fifty in depth; two

were held by each establishment. The cost of a cod seine crew amounted,

for the season, to 6,000 livres, and the catch thereof to 1,200

quintals. The allowance for each man for the season, commencing at the

first day of May and ending on arrival in France, on or about the first

day of November, 35 lbs. pork, 35 lbs. butter, 3J cwt. bread, 40 lbs.

peas, 6 gallons of brandy, f tierce cider— in all equal to about £8.

sterling ; boat-masters, or principal men, are paid about £10 as wages,

an ordinary fisherman £7, and boys £3 less, a sum equal to £2 10s.

allowed on each man as a bounty by their government. In 1829, their

catch of fish amounted to 350,000 quintals—45 quintals for each person

employed—an average catch and good voyage.

“At this period their

bounties were extremely liberal, therefore, supposing the merchants were

allowed on each man employed 60 livres, or 50s. each on 13,566 men,

£33,915.

“£171,415 sterling paid

in bounty, besides materials granted the fisherman in addition. In fact,

the fishery is for the purpose of training seamen for their navy, and

consequently is a national undertaking rather than the pursuit of

private individuals.”

The following account

of the French fisheries is given by Commander Fortin to the Canadian

Government in 1862

“France looks upon the

Newfoundland fisheries as the true school for the French marine, and it

is here that she forms the nursery of hardy sailors whom she requires to

man her fleets ; and of so great importance does she consider them to

be, that she every year employs for their protection three steam war

vessels and two armed schooners.

“Numerous laws,

regulations and decrees of the commandant of St. Pierre regulate the

French fisheries at Newfoundland; but I do not consider it necessary to

dilate here upon any of them except those which relate to the cod

fishery carried on on the coast of that island, and the possession of

the land necessary for the working of this branch of industry.

“The vessels which are

fitted out in France for the New foundland fishery are divided into

three classes:

“1st class.—Vessels

over 158 tons and under 400 tons.

“2nd “ — “ “ 100 “ “ 158 “

“3rd “ — “ under 100 “

“The proprietors of the

vessels of these various classes draw lots every five years for the

right of occupying the various fishing settlements on the coast ; the

best numbers select the best fishing posts, and so on to the least

advantageous.

“This system of

distributing the fishing posts has been found to be the most

satisfactory to the fishermen, although it is not unattended with

inconvenience; for instance, it prevents rich outfitters from making

large well-fitted establishments, because, at the end of five years,

they would run the chance of seeing them pass into other hands; for no

fisherman is allowed to remove anything from his establishment when the

drawing of lots takes place.

“The last drawing took

place this spring, and there were one hundred and eleven vessels in the

first class, and nearlj as many in each of the other two.

“Vessels of the first

class should have a crew of at least sixty-five men and boys; of the

second, forty-five; and of the third, thirty ; which give a total of ten

or twelve thousand fishermen employed in the French fisheries on the

coast of Newfoundland, from Cape St. John on the east to St. George’s

Bay on the west.

“The principal

regulations which relate to the cod fishing are those which forbid the

use of deep sea or trolling lines in the taking of that fish, and only

allow the use of cod fish nets afloat; all fishermen are strictly

forbidden to draw or land a cod fish net, or even a caplin net on the

shore, without doubt, in order that those fish may not be disturbed

while engaged near the shore in the reproduction of their species.

“The French do not make

much use of the line in the cod fishery on the north coast of

Newfoundland. They use chiefly very large nets which are nearly all 150

fathoms long and 30 fathoms wide. Nearly forty men are required to

handle them successfully ; they are very costly. But on the other hand

vast quantities of fish are taken with these immense nets ; 50, 100, and

even as many as 200 quintals of cod, or 5,000, 10,000 and 20,000 fish.

“But it is a necessary

condition that the fish should run in shoals and be plentiful on the

fishing grounds; unless this is the case, the net fishing yields but

little, and the outfitter’s loss is then enormous.

“The cod this year was

not plentiful on the coast of Quirpon, and the fishermen of that place,

including Messrs. Robinot and Durand, had in consequence suffered a

proportionate loss, as they have but little cod to export, and will

accordingly receive but a small sum as premium.

“There are at Quirpon

seven fishing establishments belonging, for the most part, to St. Malo

and St. Servan; these employ eighteen ships of from two to five hundred

tons. We saw one of them, a fine ship of 500 tons, sail with a cargo of

dried cod fish for the Bourbon Islands and the Mauritius, which are in

great part supplied with fish by the French.

“The French fishermen

are compelled to bring from France almost everything which they require

in carrying on their business ; lumber, boards, planks, pieces of elm

aril oak to repair their boats and vessels, flour, pork, butter, &c.,

&c., the island of Newfoundland not producing any of these articles.

And of these they

consume every year a very large quantity, and the cost of such articles

in France is generally much greater than in Canada ; and it certainly

would bo greatly to the advantage of the French fishermen to come and

buy of us the greater part of the supplies which they require.

“But it may be asked :

if there is any profit to be made, how is it that the French shippers

have not before now taken advantage of the low prices in our market, and

why, on the other hand, have not the Canadian traders entered into

commercial relations with the French fishermen, and despatched to them

cargoes of flour, provisions and wood, suitable to supply their

requirements

“To this I reply that

it results from two principal causes. In France little is known of the

varied resources of Canada, and here, until late years, the nature,

extent, importance and requirements of the French fisheries at

Newfoundland have been ignored.

“For more detailed

information on this subject, my report of 1S58 on St. Pierre and

Miquelon may be consulted.

“I do not pretend, and

I do not wish to be understood, to say that very important commercial

relations could be established between the Canadian traders and the

French shippers and fishermen of Newfoundland; but what I consider quite

possible, and what I am desirous of seeing realized for the mutual

benefit of shipper's and traders, both Canadian and French, in

Newfoundland, is that Canada, and principally Quebec and (laspc, should

supply the latter with the wood and the provisions which are

indispensable to them, and should in return receive French products,

especially French cordage, which is of superior quality, and of which

the consumption on our ships would be very great.

“This trade would give

employment to ten of our schooners to begin with, and at a later period

that number would increase.’'

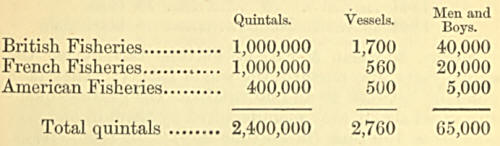

The French annually

employ about 560 vessels in the Newfoundland fishery, of from 100 to 500

tons burthen, manned by upwards of 20,000 fishermen. About half of this

number prosecute the Bank fishery from the French Islands of St. Pierre

and Miquelon, on the south-west coast; the other half at the French

shore on the northern coast. The quantity of fish taken by them is

estimated at over 1,000,000 quintals annually. The amount of bounties

paid in 1828 is said to have been $625,000; in 1832, $300,000; and in

1846, $905,000. (For an account of the fisheries of St. Peters’, see

Fortune Bay).

The British Fisheries

of Newfoundland, in some places, commence in May, and at other places,

not until the middle of June. About the beginning of June the vessels

sail for the Labrador Fishery. The manner of catching and curing the

fish has been so often described, and is now so well known, that it is

unnecessary for me to repeat it here.

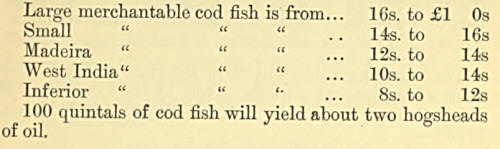

The price of fish is

regulated by the demand of the foreign markets.

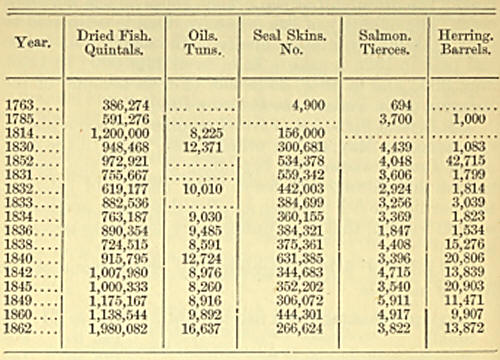

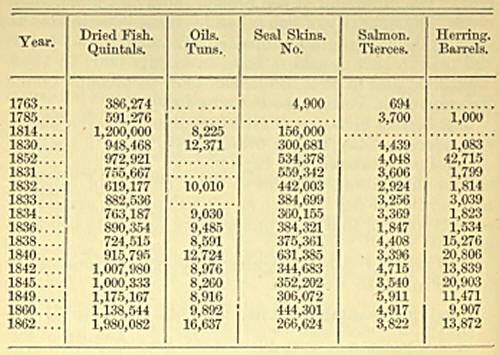

The following is the

produce of the British fisheries of Newfoundland at different periods,

all of which were exported:

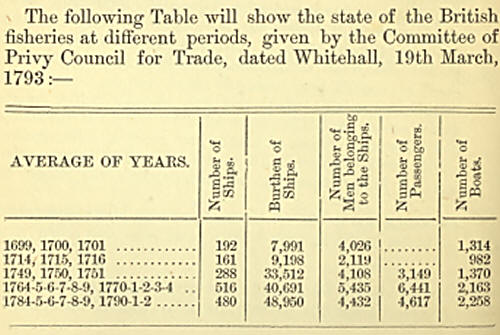

The following Table

will show the state of the British fisheries at different periods, given

by the Committee of Privy Council for Trade, dated Whitehall, 19th

March, 1793

The number of vessels

employed in the Fisheries is about 800, from 80 to 180 tons burthen,

besides coastwise. There are 1,300 more vessels employed in the Foreign

Trade, principally in carrying fish and oil to market. The number of

boats employed in the fishery is 11,693, capable of carrying from 4 to

100 quintals of green fish. The number of persons employed in the

Newfoundland and Labrador Fishery, is about 50,000. The Labrador Fishery

is principally carried on from the Ports of St. John’s. Harbour Grace,

Carbonear, and Brigus. (For a more detailed account, see Labrador).

The following account

of the Labrador Fishery is given by Mr. McGregor:

“During the fishing

season, from 280 to 300 schooners proceed from Newfoundland to the

different fishing stations on the coast of Labrador, where about 20,000

British subjects are employed for the season. About one-third of the

schooners make two voyages, loaded with dry fish, back to Newfoundland

during the summer; and several merchant vessels proceed from Labrador

with their cargoes direct to Europe, leaving, generally, full cargoes

for the fishing vessels to carry to Newfoundland. A considerable part of

the fish of the second voyage is in a green or pickled state, and dried

afterwards at Newfoundland. Eight or nine schooners from Quebec frequent

the coast, having on board about 80 seamen and 100 fishermen. Some of

the fish caught by them is sent to Europe, and the rest carried to

Quebec; besides which, they carry annually about £6,000 worth of furs,

oil and salmon to Canada. From Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, but

chiefly from the former, 100 to 120 vessels resort to Labrador: the

burden of these vessels may amount to 6,000 or 7,000 tons, carrying

about 1,200 seamen and fishermen. They generally carry the principal

part of their cargoes home in a green state.

“One-third of the

resident inhabitants are English, Irish, or Jersey servants, left in

charge of the property in the fishing rooms, and who also employ

themselves, in the spring and fall, catching seals in nets. The other

two-thirds live constantly at Labrador, as furriers and seal-catchers,

on their own account, but chiefly in the former capacity, during winter,

and all are engaged in the fisheries during the summer. Half of these

people are Jerseymen and Canadians, most of whom have families.

“From 16,000 to 18,000

seals are taken at Labrador in the beginning of winter and in spring.

They are very large ; and the Canadians, and other winter residents, are

said to feast and fatten on their flesh. About 4,000 of these seals are

killed by the Esquimaux. The whole number caught produce about 350 tons

of oil—value about £8,000. There are six or seven English houses, and

four or five Jersey houses, established at

Labrador, unconnected

with Newfoundland, who export their fish and oil direct to Europe. The

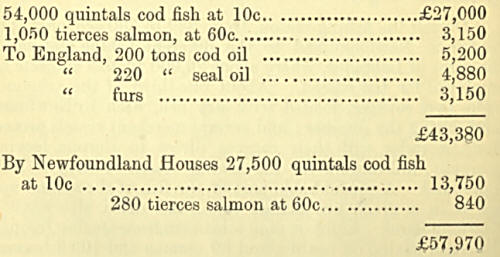

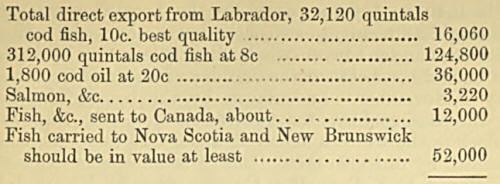

quantity exported in 1831 to the Mediterranean was about—

Estimated value of the

produce of Labrador, exclusive of what the Moravians send to

London£302,050

“These statements are

made at the most depressed prices, and not at the average prices, which

would increase the gross value to £342,400.”

It is estimated, that

the Americans employ about 500 vessels, of from 50 to 180 tons burthen,

manned by 5,000 men, on the Newfoundland and Labrador coast, and the

quantity of fish taken by them is 400,000 quintals of cod fish.

The total quantity of

cod fish, taken on the Newfoundland coast annually, may be fairly

estimated as follows:—

The Whale Fishery on

the Newfoundland coast is not important. From 1795 to 1807 Massachussets

employed twelve vessels on the south-west coast. But when the war

commenced with Great Britain, the American whale fishery on the

Newfoundland coast was discontinued.

In 1840, an Act was

passed by the Local Government, offering £200bounty to each of the first

three vessels landing not less than ten tons of whale oil, or fifteen

tons of whale fat or blubber, between the first day of May and the tenth

day of November. Encouraged by the bounty afforded by the passing of

this Act, two vessels were sent from St. John’s to the western shore, of

about 120 tons each, and manned by nineteen men. One of these vessels

was sent by Messrs. C. F. Bennett & Co., the other by Messrs. Job

Brothers & Co.

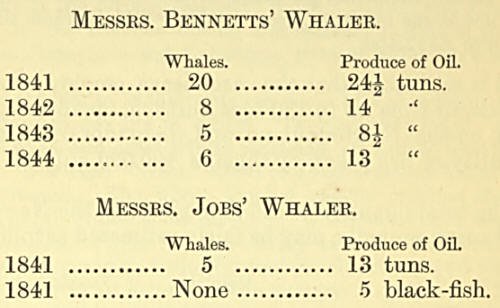

The result of each

year’s fishery was as follows :—

Messrs. Newman &; Co.,

at Fortune Bay, during the above years, also pursued the whale fishery.

They take annually between 40 and 50 whales. The greatest quantity of

whale oil ever manufactured by them in one year was about 150 tuns (in

Fortune Bay). In 1866, Messrs. Ridly, of Harbour Grace sent a vessel to

Greenland whale fisheries, she returned in September with about 50 tuns

of oil. The seal fishery of Newfoundland has assumed a degree of

importance far surpassing the most sanguine expectations of those who

first embarked in the enterprise, and is now become one of the greatest

sources of wealth to the country. The interest of every individual is

interwoven with it, “ from the bustling and enterprising individual,

that, with spy-glass in hand, paces his wharf, sweeping ever and anon

the distant horizon for the first view of his returning argosy, to the

emaciated little broom-girl that creeps along the street, hawking her

humble commodity from door to door.”

The return of a ‘‘Seal

Hunter” reminds one of Southey’s beautiful poems, “Madoc,” and

“Roderice, the last of the Goths.” “The Return to Wales” is thus

described :—

“Fair blew the wind, the

vessel drives along,

Her streamers fluttering at their length, her sails

At full; she drives along, and round her prow

Scatters the ocean spray. What feelings then

Fill’d every bosom, when the mariners,

After the peril of that wary way,

Beheld their own dear country! Here stands one

Stretching his sight towards the distant shore;

And as to well-known forms his busy joy

Shapes the dim outline, eagerly he points

The fancied headland, and the cape and bay,

Till his eyes ache o’er straining. This man shakes

His comrade’s hand, and bids him welcome home,

And blesses God, and then he weeps aloud:

Here stands another, who, in secret prayer,

Calls on the Virgin and his patron Saint,

Renewing his old vows, and gifts and alms,

And pilgrimage, so he may find all well.

* * * *

Fair smiled the evening,

and the favouring gale

Sung in the shrouds, and swift the ready bark

Rush’d roaring through the waves.”

In the commencement,

the seal fishery was prosecuted in large boats, which sailed about the

middle of April; and as its importance began to be developed, schooners

of from 20 to 40 tons were employed in it. These sailed on the 17th of

March. The vessels employed in this fishery are from 50 to 160 tons,

manned by from 25 to 40 men each, according to the size. They sail from

the 1st to the 10th of March. The length of time spent on the voyage is

from three to eight weeks, sometimes, however, a “trip” is taken in a

fortnight, of 5,000 seals, amounting in value to nearly £3,000. The

owner supplies the vessel with provisions and every other necessary. One

half the product of the voyage is equally divided among the crew, the

other half goes to the owner of the vessel. The crew have to pay from

ten to thirty shillings each for their “berths.” A hired master receives

from four pence to six pence per seal, and sometimes five pounds per

month besides. A man’s share is allowed to the master, which, however,

goes to the owner of the vessel. What is called the seal is the skin

with the fat or blubber attached, the carcase being thrown away. Some

years back these pelts were sold for so much apiece, varying in price

according to the size and quality; but in consequence of the practice of

leaving behind a portion of the fat, it became necessary to purchase

them by weight. The price of the young seals is usually twenty-two

shillings, and the old twenty shillings per hundred weight; the price,

however, is regulated by the value of oil in the British market. The

sailing-vessels have now been mostly superseded by steamers. The

following account of the seal fishery is very truthfully and beautifully

given by Mr. Nugent, formerly Member of the House of Assembly, and late

High Sheriff of Newfoundland.

“The Seal Fishery of

Newfoundland is confessedly one of the greatest sources of wealth of

which this country can boast, and in its prosecution are combined a

spirit of commercial enterprise, a daring hardihood and intrepidity

without parallel.

Towards the close of

the month of February, and in the beginning of March, the seal usually

whelps, and in the northern seas they gather around the ice fields and

deposit their young upon the ice in myriads. In order, therefore, to

arrive at the haunts of the seal at <? time when the cubs are some three

weeks old, for then are these animals easiest caught, and their fat is,

at the same time, purer and in greater quantity than when they are more

grown—the sealing vessels leave, our southern ports about the first of

March, and proceed to the northward to seek those icebergs and floating

fields of ice, which by all other mariners are looked upon with terror

and dismay, and, once coming up to the seals, they plunge into the midst

of the ice.

“The intrepid seal

hunters now pour forth upon the expanse of ocean, and rush upon their

prey far away from their vessel, bounding from mass to mass along the

glassy surface of the frozen deep. Here you see one leap across a chasm

where yawns the blue wave to engulph him. There, another, amid the mist,

mistakes a mass of slob or soft snow for an ice-pan and is buried in the

ocean, whence, sometimes, he is rescued from his peril by the timely aid

of his associates, if they be near, at others, he sinks to rise no more.

Anon comes the thick freezing snowdrift, that shuts out all ken of

neighbouring objects, and the distant ship is lost. The bewildered

sealers gather together, they try one course, then another, but in vain,

no vessel appears: the guns fired from the vessel are unheard, the

lights unseen : night comes on and with it hunger, and the blasting

wind, and the smothering snow overwhelm the stoutest, and many, very

many, yielding to fatigue and mental misery, sink into despondency, and

the widow’s wail and the orphans’ cry, are the only record of the

dreary—of the dreadful death of the sealer.

“We speak not of the

peculiar tempestuous season in which they are engaged—the Vernal

Equinox. We speak not of the vessel crushed between the icebergs,

consigning all to a tremendous fate, or of the thousand other disasters

to which even these iron-bound ships are liable, but may say, in a word,

that scarce a season passes that we have not to deplore the loss of

vessels, of crews, or of individuals, leaving many a bereft mother, a

widowed wife and orphaned child, to heave a heart-rending sigh o’er the

memory of the sealing voyage.

“But, even when death,

in its most fearful form, puts not a sudden period to the sufferings of

the sealer, the toils, and hardships, and perils of this voyage are

indescribable ; while he has nought to sustain him, nought to buoy him

up, but the fond hope of being able, by the produce of his industry, to

realize a temporary provision for an affectionate wife and children.

“Never, indeed, was

there an adventure in the prosecution of which are combined more of

commercial enterprise on the one hand, and of nerve, of strength, of

vigour, perseverance and intrepidity—manly and dauntless daring—on the

other. The merchants adventurously contribute the outfit—consisting of

the vessel with all her materials fully equipped and victualled. The

fisherman contributes his toil, his dangers, his life— all the hopes,

the fortunes, the fate of his family. Thus is the Seal Fishery a

lottery, where all is risk and uncertainty, but still, the risk, we must

confess, is not equally, or even proportionally distributed.

“We shall take for

instance one vessel of about 120 tons. In her success is involved the

success of one merchant—he may gain £1,000 or more, if the voyage

prosper. In her success is involved the success of some thirty

fishermen—they may gain each from £20 to £30 ii the voyage succeed. The

merchant to run the chance of gaining £l,000 has risked a capital of per

haps £2,000. The sealer to gain from £20 to £30 has devoted an

incredible amount of toil and suffering—he has risked all— his life. If

the voyage fail, the merchant has still his ship, &c., lie has suffered

an actual loss of the provisions consumed on the occasion. If the voyage

be unsuccessful the poor man returns with the loss of his labour,

pennyless. If the vessel founder, or be dashed to pieces in the ice, the

insurance officer relieves this one merchant by compensating him for his

actual loss. If the vessel founder, thirty valuable lives are

lost—thirty widows, anil perhaps one hundred orphans shriek their curses

upon a fishery that brought upon them miseries that cannot be

compensated—the grave of all their hopes—the dawn of every misfortune.

“Thus, then, is the ri&k

to all great—to the poor man immense. The property of the merchant is

perilled, the life of the fisherman, infinitely more valuable than any

amount of property ; and if* this, piincipally, consists the disparity

of the hazard at both sides. Let us, now, enquire after what maimer each

party is compensated for his respective risk.

“Upon the return of the

sealing vessel, one half of the proceeds of the industry of the men is

handed over to the merchant, in remuneration for the capital he had

advanced in the first instance. The other half is divided amongst the

men, whose toil and daring procured it; but then, the merchant’s half is

given perfectly clear and unencumbered of all charges, of every

deduction—the poor man’s half is clipped and curtailed—he is, first,

obliged to pay hospital dues; and, further, beside giving the merchant a

full and undiminished half of the entire voyage, he is still further

taxed by the merchant, to whom he is obliged to pay a sum of money, not

only for the very materials used in its prosecution, but actually, a

further sum for the privilege of being allowed to hazard his life to

ensure a fortune for the merchant, and both of these latter charges

combined are here both technically denominated ‘Berth Money.’

“The question of the

amount of berth Money has agitated the sealing population for many

years, and still, was its tendency rather to increase than diminish ;

but, at length, the sealers determined to procure a reduction of the

charge, and, in order to effect this, they, on Monday last, held a

meeting on the Barrens, and passed a number of resolutions pledging

themselves to ‘ the adoption of every constitutional means ’ to ‘defend

their rights’.— to refrain from entering upon the voyage until the

merchants should consent to reduce the Berth Money from £3 10s. per man,

to £2 for common or ordinary hands, called bat’s men, £1 for after

gunners, and bow gunners free; and to this they added a resolution

pledging themselves ‘ not to use any coercive means ’ for the operation

of their object.

“From that day forward

the whole body, probably, amounting to from 1,000 to 2,000 men, as fine

fellows as could be seen in any country, marched through the streets

cheered by a fiddle and drum, aud with colours flying, and so far was

there not the slightest infraction of the law, and the exemplary

sobriety that distinguished them, gave hope to all who felt an interest

in them, that the peace and order of the community would not be

disturbed.”

The meeting of the

sealers referred to in the preceding article by Mr. Nugent, took place

in St. John’s on the 18th March, 1842. The berth money that year had

been raised by the merchants and owners of vessels to three pounds, and

three pounds ten shillings currency for “ batmen,” and one pound for bow

or chief gunner, who had hitherto gone free. Some of the parties

committed a trifling breach of the peace and were imprisoned for a short

time; the berth money, however, was lowered, to two pounds for batmen,

one pound ten shillings for after gunner, and the bow gunner free as

before. The batman is the person who kills the seal with a long handled

gaff* similar to a boat hook. The number of vessels usually employed in

the Seal Fishery is about 350, from 60 to 180 tons, manned by 10,000

men. The number of seals taken per annum is 500,000, amounting in value

to 1,500,000 dollars.

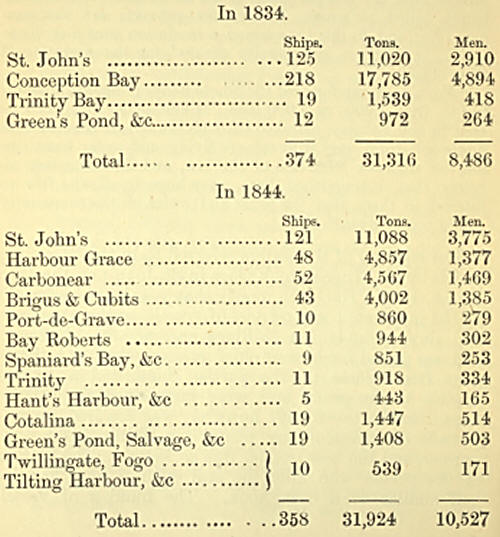

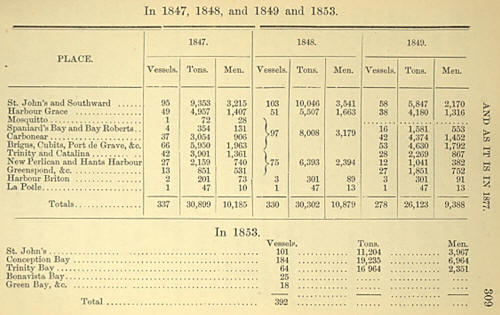

The following tables

will show the number of vessels employed in the Seal Fishery throughout

Newfoundland from 1834 to 1849, and in 1853.

In 1866, there was a

great falling off in the outfit for the Seal Fishery. The Messrs.

Grieve, and Bearings, of St. John’s, and Messrs. Ridley & Sons, of

Harbour Grace, sent a steamer each, which returned well filled.

In the year 1871, there

were 201 sailing vessels and 13 steamers, manned by 9,791 men.

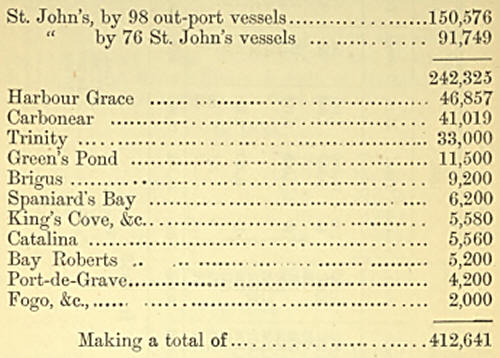

The following is the

number of seals landed at the several ports of the island in the spring

of 1839:—

NUMBER OF SEALS

MANUFACTURED AT THE SEVERAL PORTS OF THE ISLAND, UP TO 31ST MAY, 1845.

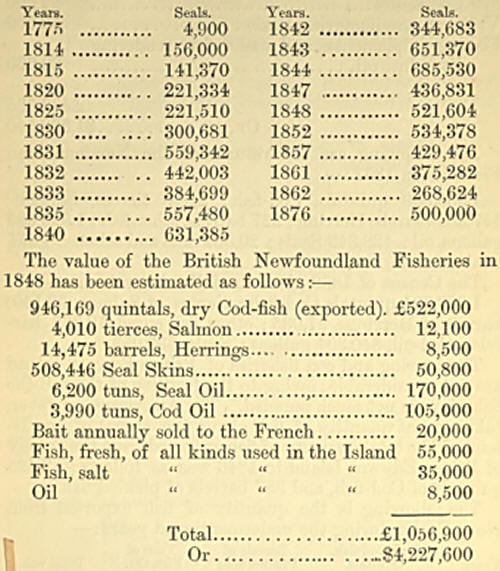

The number of seals

taken at different periods was as follows:—

The produce of the

fisheries in the District of Gaspd, and the Magdalen Islands in 1836,

consisted of Cod, 100,542 quintals ; Cod oil, 37,162 gallons; Whale oil,

25,120 gallons, besides salmon and other fish, the whole amounting in

value to £86,624, or $336,496.

Captain Fair of H.M.S.

Champion, in 1839, says, when speaking of the Magdalen Islands,—

“We found tlie herring

fishing had commenced, and was in active operation in the several parts

of the Bay (chiefly in the little harbours of Amherst and House Harbour)

by about 146 sail of American fishing schooners, of from sixty to eighty

tons, and each carrying seven or eight men. Among them were not more

than seven vessels belonging to the British possessions, and they

chiefly from Arichat. The quantity of herrings was very great, exceeding

that of any former years, and the expertness and perseverance of the

American fishermen were far beyond that of the Arichat men* It is

computed that the American fishing schooners average nearly 700 barrels

each, and the barrel is valued at one pound sterling, making, for the

146 sail then in the Bay, a presumed product of 100,000 barrels, value

£100,000 sterling ; the tonnage employed about 10,000 ; and the number

of men about 1,000.

“Between the last end

of Prince Edward Island, to within seven leagues of the Bay of Chaleur,

we passed through a fleet of from 600 to 700 sail of American fishing

schooners, all cod fishing ; it had not been a fortunate season for them

and great numbers had gone towards the Straits of Belle Isle for better

success.

“The house of Janvrin &

Co., at Gaspd, exported in the year 1836 from 15,000 to 20,000 quintals

of Cod-fish, chiefly for the Brazils and South America. Other minor

establishments export largely also—perhaps from Gasp6 and its

neighbourhood the whole export may be about 40,000 quintals.”

In the District of

Gasp6, Cod-fishing is divided into the summer and fall fishing. The

former begins in May, and last till the 15th of August. The fall fish is

either dry, salted or pickled in barrels, the greater part of which is

sent to the Quebec Market.

When the writer

arrrived at Paspebiac in the Bay of Chaleurs, District of Gasp6, in

1864, he found over a dozen barques, brigs and schooners, most of them

taking in fish for the foreign markets.

Here is situate two of

the largest fish establishments in Canada. The business is conducted in

the same manner as the large out-harbour establishments in Newfoundland

in the olden times. Here is the well known firm of Charles Robin & Co.,

of St. Helier’s, Island of Jersey, which was established in 1768. They

have branch establishments at Perc£, Caraquette and other places. They

export from 40,000 to 45,000 quintals of dried codfish, to the various

markets of Spain, Portugal, Brazils, West Indies and Mediterranean

Ports, besides 30,000 gallons of oil, herring, salmon, etc. The Messrs.

Le Boutillier Brothers have also branch establishments at Bonaventure

Island and Labrador, and export altogether about 25,000 or 30,000

quintals dried codfish, besides herrings, salmon and furs. Here is also

the firm of Daniel Bisson, and several minor establishments.

Besides the Canadian

ocean fishery, a very extensive fishery, in salmon trout, white fish,

pickerel, pike, bass etc., is caried on in the Canadian great fresh

water lakes and rivers. The Canadian codfish is small compared with

Newfoundland and neither so firm nor so fat, and the reason of the Gaspd

fish commanding a higher price in the foreign market, is because it is

taken and cured in smaller quantities, and less salted than the

Newfoundland fish.

The river fisheries

carried on off the coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and of the Lower

St. Lawrence, at the island of Anticosti, at the Magdalen Islands, and

on the Gasp6 coast, form an extent of over 900 miles of sea coast,

inhabited by a population of over 35,000 English, Scotch, Irish,

Jerseymen, and French Canadians; the last named predominate. The coast

is frequented each year between the opening and closing of navigation by

more than 1,500 fishing schooners from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick,

Prince Edward Island, and the United States, manned by at least, 20,000

sailors, 'who go there for the purpose of carrying on the cod, herring

and mackerel fisheries.*

The amount of fishing

bounties paid by the Canadian Government in 1863, was 9,769 dollars.

The fishery expenditure

from the 1st July, 1864, to 30th June, 1865, was in Lower Canada 17,500

dollars, including a sum of 6,938 dollars paid for fishery bounties for

the year 1864; and in Upper Canada, 1,053 dollars. The collections made

in Lower Canada (from fishery licenses), during the same period amounted

to 4,854 dollars; and in Upper Canada, 816 dollars.

M. H. Perley, Esq., Her

Majesty’s British Commissioner for the Fisheries at St. John, New

Brunswick, very politely sent me a copy of his Report on the Fisheries

of New Brunswick, from which I make the following extracts :—

“Just within Shippagan

Gully, on Shippagan Island, in a well sheltered and very convenient

position, is the fishing room of Messrs. Wm. Fruing & Co., of Jersey, of

which Captain George Alexandre, of Jersey, was found in charge. At this

place there were sixty boats engaged in fishing, averaging two men and a

boy to each boat. It was stated, that each of these boats would probably

take 100 quintals of fish during the season, but that the boats

belonging to the firm, manned by Jer-seymeu, would take more. On the

21st August there were at this ‘ room ’ 2,500 quintals of dry fish,

exceedingly well cured. On the day it was visited there were 600

quintals of cod spread out to dry; they were exceedingly white and hard,

of the finest quality, and were about to be shipped to Naples, lor which

market the very best fish are required. They are shipped in bulk, and

the manner in which they are stowed in the holds of the vessels is very

neat and compact. It requires great skill and care to stow them without

breaking, and in such a manner as to prevent their receiving damage on

so long a voyage; but long practice and experience have conquered these

difficulties, and cargoes are rarely injured by bad stowage.

“The ling cured at this

establishment are sent to Cork tor the Irish market; and the haddock to

the Brazils. The first quality cod cured here in 1848, instead of being

sent to Naples were shipped to the Mauritius; it was not stated what

success had attended this adventure.

“Nearly all the

fishermen at this establishment were French settlers, who had small

farms, or patches of land, somewhere in the vicinity, which they

cultivated. It was the opinion of Captain Alexandre, that the fishermen

could not live unless they possessed land, and obtained something from

the soil; if they did not, they nearly starved. Those who are too poor

to own boats hire them of the firm for the season, that is, until the

15th of August, when the summer fishing ends. If the boats are used for

the autumn or ‘ fall' fishing, there is, of course, another hiring.

“The fishing usually

continues until the 15th October, and it was expected that the whole

catch of the season of 1849 would amount to 3,500 quintals—if the

weather proved favourable, probably 4,000 quintals.

“The boats come in here

directly to the ‘stage head,’ upon which the fish are thrown ; they are

at once split and cleaned by the fishermen, on tables provided for the

purpose; and 300 lbs. of fish fresh from the knife, are weighed off as

sufficient to make a quintal of dry fish, with the allowance of

One-tenth for the curer. If the fish are split and salted in the boats,

and lay one night, then 252 lbs. are weighed as a quintal. The fishermen

are allowed for a quintal of cod thus weighed, ten shillings, and for

ling and haddock, five shillings,—the amount payable in goods at the

store of the firm, on Point Amacque, where a large quantity of foreign

goods is kept of every variety. Here were found Jersey hose and

stockings—Irish butter— Cuba molasses—Naples biscuit, of half a pound

each—Brazilian sugar—Sicilian lemons—Neapolitan brandy—American

tobacco—with English, Dutch, and German goods,—but nothing of Colonial

produce or manufacture, except Canadian pork and flour.

“Some of the residents

at Shippagan, who are in more independent circumstances, prosecute the

fisheries in connection with their farming, curing the fish themselves,

and disposing of them at the close of the season to the Jersey

merchants, or to others, as they see fit.

“All the men engaged in

this fishery are also part farmers ; they cultivate some portion of land

wherever they reside on the coast. Of the quantity of dried fish above

stated, it is estimated that 15,000 quintals were cod, and the rest

haddock and ling.

“The ling is a fish

known in the Bay of Fundy by the name of ‘ Hake.’ In the Gulf this fish

is taken of very large size, especially by fishing during the night. In

appearance it corresponds precisely with the drawing in Mr. Yarrell’s

admirable work on British Fishes, (vol. 2, page 289,) and its

description is the same as there given of the forked hake ; or phycis

furcatu8 of Cuvier. Owing to the length, breadth and thickness of the

ling when split, they are, at the best ‘ rooms,’ dried on large flakes,

raised about eight feet from the ground, which have a greater

circulation of air underneath. The cod of larger size are also dried on

these flakes.

“Of the quantity of

fall herring taken on this coast, it is quite impossible to give any

estimate which may be relied upon as accurate. The principal fishing

ground is at Caraquette, and the whole quantity taken there in 1849,

would probably amount to two thousand barrels, or perhaps exceed that

quantity. The catch at other localities along the coast, would perhaps,

amount to one thousand barrels more.

“The quantity of

mackerel caught and cured, is so small as scarcely to be taken into

account, in giving an estimate of these fisheries. It was said that

mackerel had at times been imported from Arichat for the use of the

inhabitants on this coast, near which thousands of barrels, of the same

fish, are annually caught by fishing vessels from Maine and

Massachusetts.”“ The value of all imports at the port of Gasp6 in 1849,

was £32,286 currency ; the value of exports the same year, was £51,880

currency. At New Carlisle, the value of imports from abroad, in 1849,

was £12,511 sterling; the value of exports was £37,250. The imports and

exports to and from Quebec are not stated in the return from New

Carlisle. The exports include birch and pine.

Fisheries of the United

States.

The number of persons

employed in the New England States before the revolution was about

4,000, which was prosecuted in small craft. The quantity caught was

about 350,000 quintals, of the value of £200,000,

“The Americans follow

two or more modes of fitting-out for the fisheries. The first is

accomplished by six or seven farmers or their sons building a schooner

during the winter, which they man themselves (as all the Americans on

the sea-coast are more or less seamen as well as farmers), and after

fitting the vessel with necessary stores, they proceed to the banks,

Gulf of St. Lawrence, or Labrador, and loading their vessels with fish,

make a voyage between spring and harvest. The proceeds they divide,

after paying any balance they may owe for outfit. They remain at home to

assist in gathering their crops, and proceed again for another cargo,

which is salted down and not afterwards dried—this is termed mud-fish,

and kept for home consumption. The other plan is, when a merchant, or

any other owning a vessel, lets her to ten or fifteen men on shares. He

finds the vessel and nets. The men pay for all the provisions, hooks and

lines, and for the salt necessary to cure their proportion of the fish.

One of the number is acknowledged master, but he has to catch fish as

well as the others, and receives only about twenty shillings per month

for navigating the vessel; the crew have five-eighths of the fish

caught, and the owners three eighths of the whole.”

For a more detailed

account of the fisheries of Massachusetts and the United States, see “A

Peep at Uncle Sams Workshop, Fisheries, &c.,” by the Author.

The annual quantity of

cod-fish exported from the United States is about 200,000 quintals,

which is principally sent to Cuba, Hayti, West Indies, and Madeira. In

1851, 502 ships, 24 brigs, and 27 schooners of the aggregate tonnage,

171,971, were employed in the whale fishery of the United States. An

important fishery is carried on in the interior lakes of America,

principally on Lake Huron, Lake Superior, Mackinac and Detroit River.

The kind of fish caught is sturgeon, salmon-trout, Maskinonge, pickerel,

mullet, white-fish, bass, pike, perch, &c. Some of these fish weigh from

one to 120 lbs. The quantity of fish taken on these lakes in 1840 was

35,000 barrels, amounting in value to 256,040 dollars.

Mr. McGregor, in his

“Progress of America,” says :—

“The British whale

fishery, formerly so very extensive, has, from causes which have

developed their effects during the last ten years, declined rapidly ;

and there is every probability that both the northern and southern

British whale fishery will be discontinued from the ports of the United

Kingdom. The substitution of vegetable and lard oils, and stearine from

lard, the great outlay of capital in the southern whale fishery, the

long period which must expire before any return can be realized for the

expenditure, constitute the chief causes of the decline of the whale

fishery from British ports. The Dutch whale fishery disappeared in the

early part of the present century ; the French whale fishery is only

maintained by bounties taken from the national taxes, and we can

scarcely hope that it can ever be revived so as to constitute a

profitable pursuit from any port in Europe. The bounties paid in support

of the British whale fishery, according to McPherson, from 1750 to 1788

amounted to £1,577,935 sterling; and Mr. McCulloch estimates that more

than £1,000,000 has been paid after that period, so that more than

£2,500,000 sterling have been paid by the nation for bounties to the

whale fishery.”

The number of ships

engaged in the northern and southern whale fisheries during the years

1843, 1844 and 1845 were as follows:—

|

Northern

Fishery. |

Southern

Fishery. |

|

Years. |

No. Ships. |

Years. |

No. Ships. |

|

1843 |

24 |

1843 |

50 |

|

1844 |

32 |

1844 |

47 |

|

1845 |

34 |

1845 |

44 |

Twenty-one ships are

engaged in the southern fisheries from the Australian colonies. Six

ships from St. John, New Brunswick, and one ship from Halifax, Nova

Scotia.

The next important

fisheries to those of America are those of Norway in Europe.

“The fisheries of

Norway supply an important branch of exportation, and for these

pursuits, their extensive seas and deep, commodious bays afford

unlimited opportunities. In the neighbourhood of the Lofoden Isles more

than 20,000 men find employment during the months of February and March

in taking herrings and cod. At that season the fish set in from the

ocean and settle on the West Fiord banks, which run from three to ten

miles out into the water, at a depth of from sixty to eighty fathoms.

Such swarms collect for depositing their spawn, attracted by the

shelter, or perhaps some special circumstances in the temperature, that

it is said a deep sea-lead is frequently interrupted in its descent to

the bottom through these shoals (or fiskebierg, mountains of fish, as

they are called) which are found in layers, one over the other, several

yards in thickness. From North Cape to Bergen, all the fishermen who

have the means assemble at the different stations in January.

Every twenty or thirty

of these companies have a yacht or large tender to bring out their

provisions, nets and lines, and to carry their produce to the market.

Their operations are regulated by statutes contained in several ancient

codes, and, more lately by that of the 4th of August, 1827. These laws

prescribe the order and limits to be observed in fixing the stations,

the time for placing and removing the nets, and also for preparing,

salting and drying the fish. Nets, and long lines of L20 hooks at five

feet distance are used, but there is a difference of opinion which of

the two outfits is the more advantageous. The period when the season

ends is appointed by law on the 12th of June, when Lofoden and its busy

shores become deserted and desolate. The fish are prepared in two ways.

They are cured as round or stock-fish until April, after which they are

split, salted and carried to the coasts above Trondheim, or other

places. There are large flat rocky mountains, with a southern aspect,

upon which they are spread and exposed to the sun to dry. This

preparation is called klip fish, and in fine seasons is completed in

three or four weeks. The livers are used for oil, one barrel of which

may be the produce of from 200 to 500 fish according to their fatness.

The number taken is immense. In a medium year (1827) there were 2,916

boats employed in 83 different stations, accompanied by 124 yachts, with

15,324 men. The produce was 16,456,620 fish, which would be about 8,800

tons dried; there were also 21,530 barrels of cod-oil, and 6,000 of

cod-roe. Sir A. Brooks reckoned the quantity taken in a year at 700,000,

worth about £120,000, but other writers value them at £250,000 or even

£300,000. An English lobster company was established some years ago on

the west coast, and twice or thrice a week their packets sailed from

Christiansand to London. In 1830 the number of these animals exported

was 1,196,904; of roes, 21,682 barrels; of dried fish, 425,789 quintals

; and of salted fish, 300,218 barrels. The herring fishery is also an

important and thriving branch of industry. In 1819, the exports were

240,000 tons. But in 1835, which was more productive than the five or

six preceding years, they amounted to 536,000, an increase the more

remarkable considering that the population and the internal consumption

had both been augmented during that period.’’

Considerable fisheries

are carried on at British Columbia, Puget’s Sound, Alaska, and adjacent

places. Hudson Bay, at some future day, bids fair to rival the

Newfoundland fisheries. For several years past, American vessels have

resorted there for cod fishing. Salmon, herring, caplin, and other

varieties of fish abound there. At Two Rivers the Hudson Bay Company

carried on porpoise fishing for several years, where 7,749 porpoises

were taken, giving an aggregate of 193,689 gallons, or 768\ tons of oil,

worth in England upwards of £27,000 sterling.3

A new market has recently been found for herring in Sweden, several

cargoes having been shipped there from Gloucester, Massachusetts, U.S.,

and found remunerative.