|

THE winters of

Newfoundland are not by many degrees so cold as in the neighbouring

Provinces, or the Northern States, nor is the climate so changeable. In

Massachusetts the temperature sometimes changes 44 degrees in

twenty-four hours, while in Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia the

thermometer sometimes falls from to 30 and 40 degrees below zero. In

Newfoundland the instances are few of the temperature changing 20

degrees in a day. January and February are the coldest months of the

year, when the thermometer sometimes sinks below zero, but at the

coldest times not more than ten degrees below, and then only for a few

hours. It is an admitted fact that the climate of Newfoundland has

gradually undergone a change within the last forty years, and is now

much warmer than formerly. This change may in part be attributed to the

great improvement in agriculture, the draining of marshes, the clearing

of forests, and, perhaps, the more northerly direction of the Gulf

Stream. Most writers affirm that the northern parts of Europe have

become much warmer than they were a few centuries ago. St. John’s, the

capital of Newfoundland, is in 47° 33' north latitude; London, England,

51° 30'; Dublin, 53° 20', and Edinburgh, 55° 53'. Thus, St. John’s is

nearer the equator than any of the above named places, and yet, instead

of being warmer, it is much colder than Great Britain. One of the

coldest winters ever experienced in Newfoundland, was in 1818, when it

is said the thermometer frequently sank from 18 to 22 degrees below

zero. The following reports of the state of the weather were

communicated to the Yarmouth Herald by electric telegraph, in February,

1858 :—

“February 16th, 9 A.M.

Halifax, N.S.—Wind*N.W.,

thermometer 12°.

Port Hood, N.S.—Wind N.W., thermometer 6°.

Port au Basque, N.F.—Wind W., cloudy, thermometer 26°.

St. John’s, N.F.—Wind W., cold and calm, thermometer 28°.

St. John, N.B.—Wind N.W., clear, thermometer 9°.

Yarmouth, N.S.—Wind W.N.W., thermometer 16°, overcast.

February 17th, 9 A.M.

Halifax, N.S.—Wind

N.W.N., thermometer 12°.

Calais, Maine.—Wind N.W., thermometer zero.

St. John, N.B.—Wind N.W., clear, thermometer zero at 7 A.M.

St. John’s, N.F.—Wind S.W., cloudy, thermometer 31°.

Port au Basque.—Wind W., overcast, thermometer 29°.

Yarmouth, N.S.—Wind N.W., thermometer 8°.

February 18th, 9 A.M.

Halifax, N.S.—Wind W.,

clear, thermometer 16°.

Sackville, N.B.— Wind N.W, thermometer zero.

St. John's, N.F.—Wind W., clear.

Yarmouth, N.S.—Wind N.W., light snow.

The following was the

state of the weather at Amherst (which is at the head of the Bay of

Fundy, on the borders of New Brunswick) on the 30th December, 1859:—

“The current week has

been signalized by unusually cold weather for early winter.

Christmas morning,

thermometer stood 13 below zero.

26th

....................................................................................11

“

27th

....................................................................................12

“

28th

....................................................................................15

“

29th

....................................................................................17

“

30th

....................................................................................21

“

“These readings are

from a self-registering spirit thermometer in a sheltered position.”

The following are the

meteorological observations in Canada during 1875 :—

“This is a goodly blue

book of upwards of 500 pages, showing the readings of the barometer, the

temperature, velocity of the wind, rainfall, &c., as taken at the

various meteorological stations in the Dominion of Canada during 1875.

“There are many very

interesting facts mentioned. The lowest temperature marked at any of the

stations of observation in Canada during 1875 was at York Factory, where

in January the thermometer stood once at —49*5. It must be cold enough

at that station in all conscience. In November, December, January and

February, the thermometer stood there at 40 degrees below zero, and

under. Not by any means that the cold was anything like that regularly

during these months, but that it was so once or oftener during each. The

highest temperature at that station in January was - 4, and in February

— 1. In November and December the highest temperatures were,

respectively, 35*5 and 22.

“It is to be noted, to

shew how severe the month of January, 1875, was, that there was only one

station in Canada where the thermometer did not sink below zero. That

was Esqui-malt, in British Columbia. The variations at different

stations are so strange as to be scarcely explicable. Thus, in the month

to which we refer, the lowest in Cornwall, Ont., was —28*8 ; while in

Kincardine it was only — 1 *5 ; in Toronto, - 8*8 ; in Hamilton, -4*5;

and in Woodstock, —16 5; while in Quebec Citadel it was - 18*5 ; and in

Fitzroy Harbour, - 27. In Newfoundland, the lowest during that terrible

month was - 3 ; and in Manitoba, — 41*3. What was true of January was

equally so of February. With the exception of Esquimault, the

thermometer went below zero at every station in Canada, so much so as to

show that February was a much colder month than any of that year. At

Fitzroy Harbour, the thermometer in this month was as low as -42;

Toronto, -16; Parry Sound, —36*3; Stratford, —23; and Woodstock, —25. In

the Province of Quebec, the lowest was - 35; in Nova Scotia, - 29 ; in

New Brunswick, - 27-8 ; Prince Edward Island, — 17 ; Newfoundland -21;

Manitoba, 5 5 ; British Columbia, — 4 ; and North-west Territory, -41.

“The highest

temperature reached in Ontario during the year in question was in

Hamilton, in J une, when it was as high as 94*8, though Petertorough was

very nearly as high—viz., 94*3 in September.

“In Quebec, the highest

was 91 ; Nova Scotia, 85 ; New Brunswick, 86-3; Prince Edward, 85 ;

Newfoundland, 83*5 ; Manitoba, 94*3; British Columbia, 98 ; and

North-west Territory, 92.

“In Toronto, the mean

temperature for the year was 40-8 ; Hamilton, 44-1, etc. It is curious

to notice that over the whole of Ontario the mean temperature did not

vary above ten degrees, the highest being at Windsor, 44-9, and the

lowest at Seeley, 34-9. The same is true of all Canada.

“In Ontario, there was

a mean of 84*9 days of rainfall; in Quebec, 86*8; in New Brunswick, 87*1

; in Nova Scotia, 91’8; in Prince Edward Island, 115*5; in Newfoundland,

89*7; in Manitoba, 564 ; in British Columbia, 92.”—Globe, September 7,

1876.

It is very probable

that the chilling effects of the ice on vegetation would be felt much

more, were it not for the warm current from the Gulf of Mexico, which

passes along towards the Grand Bank. In Newfoundland, the coldest wind

in winter is from the North-west, from which quarter in fact the wind

generally prevails for about nine months of the year. In spring easterly

winds prevail, and in winter and summer, North-easterly winds are cold.

South, and south-easterly winds in winter are generally accompanied with

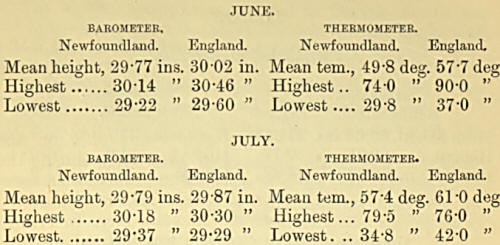

snow or sleet, and sometimes rain, and in summer rain or fog. July and

August are the hottest months in the year, when the thermometer is said

to have attained 90 degrees in the shade, but this rarely occurs. The

usual temperature of those months is from 65 to 79 degrees. The

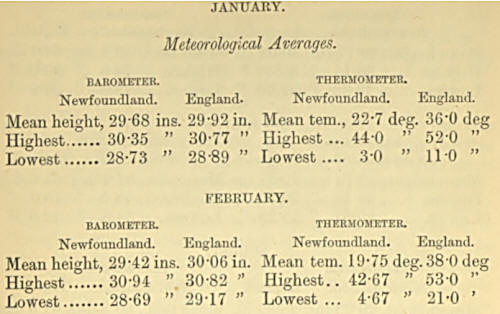

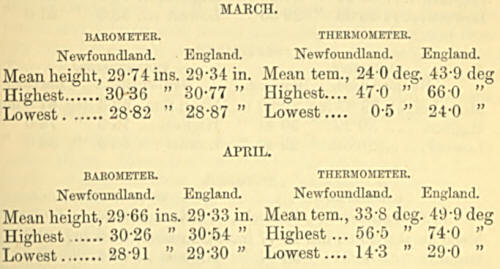

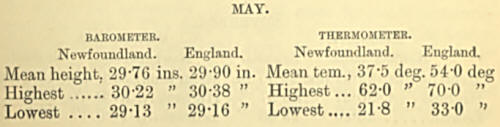

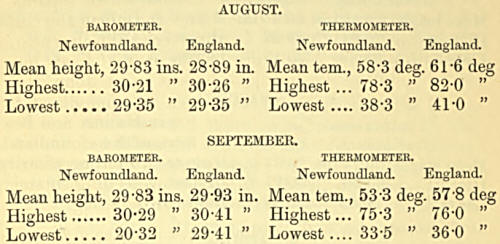

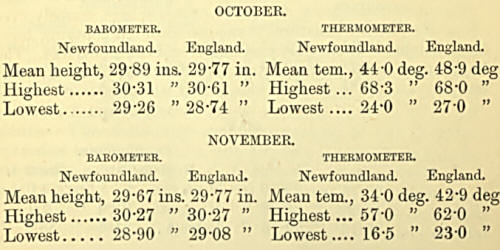

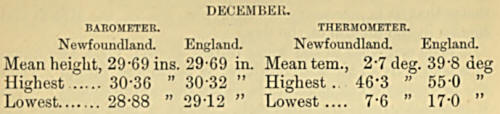

following are the averages of the thermometer and barometer for a number

of years in Newfoundland, compared with England :—

In Newfoundland the

sea-fog prevails only on the eastern and southern shores, and then only

during the summer months. I do not remember to have seen more than two

or three foggy days in a year in Conception Bay, and none on the south

shore of Bonavista Bay. In Trinity Bay, however, it obtains with south

winds, where it is brought over the narrow neck of land, which separates

that Bay from Placentia Bay. The fog along the coast from St. John’s to

Cape race, hardly ever approaches nearer than within one or two miles of

the shore. I saw more dense fog during the fortnight I spent in St.

John, New-Brunswick, than I saw in St. John’s, Newfoundland for years,

and I have seen much more fog in Halifax and Boston than I ever saw on

the eastern coast of Newfoundland. Many persons suppose that a severe

winter necessarily produces a greater quantity of fog the succeeding

summer, and that the more ice is produced—the more fog.

“The production of fog

entirely depends on the difference of temperature. There is abundance of

fog where no ice is found at all. Along the coast of Peru, the

atmosphere scarcely ever possesses sufficient moisture to produce rain;

it contains, however, enough to create widely extended and continued

fogs. The wintry season, in that country, lasts from April to October,

and throughout the whole of this period, a veil of mist shrowds sea and

shore. During the months of August and September, the vapour is

extremely dense, and rests for weeks immovably upon the earth. The fogs

are said to be at times so heavy, that the moisture falls to the earth

in large drops, which are formed by the union of small globules of mist.

England surrounded by a warm sea, is subject to thick fogs, that prevail

extensively in the winter. The London fog is so extremely dense that it

is necessary to light the gas in the streets and houses in the middle of

the day.

Fogs originate in the

same causes as rain, viz.: The union of a cool body of air with one that

is warm and humid; when the precipitation of moisture is slight, fogs

are produced; when it. is copious, rains are the result. When a mist is

closely examined it is found to consist of minute, globules, and the

investigations of Saussure and Kratzenstein, lead us to suppose, that

they are hollow, for the latter philosopher discovered upon them rings

of prismatic colours, like those upon soap bubbles, and these could not

exist if the globule was a drop of water, with no air or gas within. The

size of these globules is greater when the atmosphere is very humid, and

least when it is dry.

“When Sir Humphrey Davy

descended the Danube in 1818, he observed that mist was regularly

formed, when the temperature of the air on shore was from three to six

degrees lower than that of the stream. This is the case on the

Mississippi. During the spring and fall mists form over the river in the

day time, when the temperature of the water is several degrees below

that of the air above, and the air above cooler than the atmosphere upon

the banks. A similar state of the atmosphere occurs over shoals,

inasmuch as their waters are colder than those of the main ocean. Thus,

Humboldt found near Corunna, that while the temperature of the water on

the shoals was 54° Fall., that of the deep sea was as high as 59° Fall.

Under these circumstances, an intermixture of the adjacent volumes of

air resting upon the waters thus differing in temperature, will

naturally occasion fogs."'

“What are called the

Banks of Newfoundland are situated from one hundred to two hundred miles

eastward of the shores of Newfoundland. Mists of great extent shroud the

sea on these Banks, and particularly near the current of the G-ulf

Stream. The difference in the warmth of the waters of the Stream, the

Ocean and the Banks, fully explains the phenomenon. This current,

flowing from the equatorial regions, possesses a temperature 5J° Fall,

above that of the adjacent ocean, and the waters of the latter are from

16° to 18° warmer than those of the Banks. The difference in temperature

between the waters of the Stream and Banks, has even risen as high as

thirty degrees.

“At the beginning of

winter, the whole surface of the Northern Ocean steams with vapour,

denominated frost smoke, but as the season advances and the cold

increases, it disappears. Towards the end of June, when the summer

commences, the fogs are again seen, mantling the land and sea with their

heavy folds. The phenomena of the polar fogs are explained in the

following manner. During the short Arctic summer, the earth rises in

temperature with much greater rapidity than the sea, the thermometer

sometimes standing, according to Simpson, at 71° Fah. in the shade,

while ice of immense thickness lines the shore. The air, incumbent upon

the land and water, partakes of their respective temperatures, and on

account of the ceaseless agitations of the atmosphere, a union of the

warm air of the ground with the cool air of the ocean will necessarily

occur, giving rise to the summer fogs.”

White, in his “Natural

History of Selborne,” says :—

“Places near the sea

have frequent scuds, that keep the atmosphere moist, yet do not reach

far up in the country, making the maritime situations appear wet when

the rain is not considerable. Dr. Huxham remarks that frequent small

rains keep the air moist, while heavy ones render it more dry by beating

down the vapours. He is also of opinion that the dingy, smoky appearance

in the sky in very dry seasons arises from the want of moisture

sufficient to let the light through and render the atmosphere

transparent, because he had observed several bodies more diaphanous when

wet than dry, and did not recollect that the air had that look in rainy

seasons. The reason of these partial frosts is obvious, for there are at

such times partial fogs about; where the fog obtains, little or no frost

appears, but where the air is clear there it freezes hard. So the frost

takes place, either on hill or in dale, wherever the air happens to be

clearest and freest from vapour. Fogs happen everywhere, caused by tlie

upper regions of the atmosphere being colder than the lower, by which

the ascent of aqueous vapour is checked and kept arrested near the

surface of the earth.”

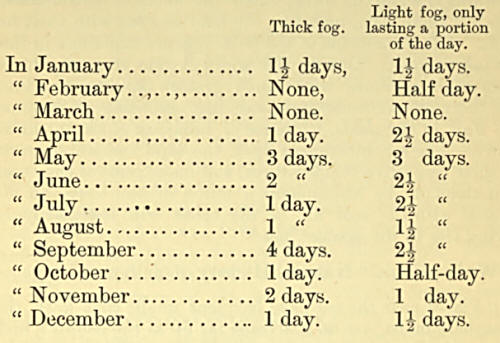

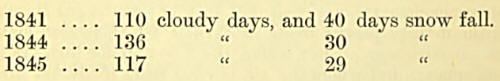

According to a register

kept at St. Johns, Newfoundland, in 1841 (it being more exposed to bank

fog than any other part of the coast), the average of thick fog and

partial light fog extending a short distance inland was as follows:—

It thus appears there

were 1TJ days of thick fog and 19 J days of light fog and mists, making

a total of only 37 days of cloudy weather throughout the year. According

to a Table kept by Dr. Woodward, Superintendent of the Lunatic Hospital,

at Worcester, which lies 483 feet above the level of the sea, and about

the centre of Massachusetts, there were, in

At Waltham, nine miles

from Boston, for 32 successive years, up to 1838, frost first commenced

from the 14th September to the 11th October.

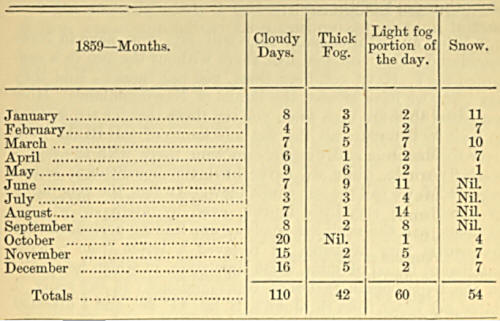

The following Register

was kept at Citadel Hill, Fort George, Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1859,

and very kindly furnished me by Mr. G. Moulds, Staff-Sergeant, Royal

Artillery:—

It will be seen from

the above statement that while in Newfoundland there were only 37 days

of thick and light fog, during the year (1841), there were, in 1859, in

Nova Scotia, 42 days of thick fog, and 60 days of light fog a portion of

the day, making a total of 112 days’ foggy weather, besides 110 days of

cloudy weather.

Bishop Mullock says:—

“By the table furnished

me by Mr. Delaney, I find the highest temperature 90° on the 3rd July;

8° on the 3rd March, and the mean temperature of the year 1859 44°; mean

max. pres, of barometer, 29-74 inch ; rain 63*920 for the year; max.

quan. in 24 hours, 2-098 inch; wind N. N. W. and W.N.W., 200 days; N.E.

25 days; W. and W.S.W. 38 days ; S.S.W. and S.E. 102 days; rain fell on

110 days; snow 54 day8 ; thunder and lightning 5 days. We have all the

advantages of an insular climate, a mild temperature with its

disadvantage, uncertain weather. I may remark likewise what Abb6 Raynal

recorded already, that the climate of Newfoundland is considered the

most invigorating and salubrious in the world, and that we have no

indigenous disease.”

Again the Bishop says:—

“What an awful climate,

they will say, you have in Newfoundland ; how can you live there without

the sun in a continual fog? Have you been there, you ask them? No ! they

say; but we have crossed the Banks of Newfoundland. How surprised they

are then when you tell them that for ten months at least in the year,

all the fog and damp of the Banks goes over to their side and descends

in rain there with the southwesterly winds, while we never have the

benefit of it unless when what we call the out winds blow. In fact, the

geography of America is very little known, even by intelligent writers,

at home, and the mistakes made in our leading periodicals are frequently

very amusing. I received a letter from a most intelligent friend of mine

some time since, in which he speaks of the hyperborean region of

Newfoundland; in my reply, I dated my letter from St. John's, N. lat.

47° 30', and I directed it to Mr. So and So, N. lat. 52°.”

Thunder storms

sometimes occur in the northern parts of Newfoundland, but are hardly

ever known in the southern and eastern parts, unless, perhaps, once or

twice in four or five years. I have never seen forked lightning in

Newfoundland, and I never heard of any one being killed by lightning in

the country. Newfoundland is admitted by all who have ever resided there

to be the healthiest country in the world. Not a fever of any kind is

generated in the country, and that fatal disease, consumption, so common

on the American Continent, is hardly known there.

From the foregoing, the

reader will perceive that the climate of Newfoundland has been

misrepresented by almost every writer.

The Aurora Borealis, or

Northern Lights, are almost constantly to be seen in the evenings, and

loaming, which is of the same nature as the mirage, is very frequent.

Admiral Sir John Ross

read to the British Association the following paper “On the Aurora

Borealis: ”—

“The communication I

had the honour of making to the British Association for the Advancement

of Science, at Belfast, on the interesting subject of the aurora

borealis, was verbal; and, therefore, not entitled to a notice in the

Association’s valuable Transactions of that period ; but, having

subsequently repeated the experiments I then verbally mentioned, I can

now confidently lay the account of them before the public, trusting

that, when taken into consideration, they will be found corroborative of

the theory which I published in the year 1819, and which led to a

controversy that shall be hereafter mentioned. It having occurred to me

that, if my theory was true, namely, ‘ that the phenomena of the aurora

borealis was occasioned by the action of the sun, when below the pole,

on the surrounding masses of coloured ice, by its rays being reflected

from the points of incidence to clouds above the pole which were before

invisible/ the phenomena might be artifically produced; to accomplish

this, I placed a powerful lamp to represent the sun, having a lens, at

the focal distance of which I placed a rectified terrestrial globe, on

which bruised glass, of the various colours we have seen in Baffin’s

Bay, was placed, to represent the coloured icebergs we had seen in that

locality, while the space between Greenland and Spitzbergen was left

blank, to represent the sea. To represent the clouds above the pole,

which were to receive the refracted rays, I applied a hot iron to a

sponge; and, by giving the globe a regular diurnal motion, I produced

the phenomena vulgarly called ‘The Merry Dancers,’ and every other

appearance, exactly as seen in the natural sky, while it disappeared as

the globe turned, as being the part representing the sea to the points

of incidence. In corroboration of my theory, I have to remark that,

during my last voyage to the Arctic Regions (1850-1), we never, among

the numerous icebergs, saw any that were coloured, but all were a

yellowish white ; and, during the following winter, the aurora was

exactly the same colour: and, when that part of the globe was covered

with bruised glass of that colour, the phenomena produced in my

experiment were the same, as was also the aurora australis in the

antarctic regions, where no coloured icebergs were ever seen. The

controversy to which I have alluded was between the celebrated Professor

Schumacher, of Altona. who supported my theory, aud the no less

distinguished M. Arago, who, hav ing opposed it, sent M. G. Martens and

another to Hammerfest on purpose to observe the aurora, and decide the

question. I saw them at Stockholm on their return, when they told me

their observations tended to confirm my theory ; but their report being

unfavourable to the expectations of M. Arago, it was never published ;

neither was the correspondence between the two Professors, owing to the

lamented death of Professor Schumacher. I regret that it is out of my

power to exhibit the experiments I have deseribed, owing to the peculiar

manner in which the room must be darkened, even if I had the necessary

apparatus with me; but it is an experiment so simple that it can easily

be accomplished by any person interested in the beautiful phenomena of

the aurora borealis.”

One of the most

beautiful appearances of nature is what is called in Newfoundland, the “

Silver Thaw,” which is also frequent in America. It is produced by a

shower of rain falling during a frost, and freezing the instant it

reaches the earth, or comes in contact with a.ny object. A most

magnificent scene is thus produced, every object is clad in a silver

robe, every twig and tree is bedecked with glittering pearls, and the

whole surface of the snow becomes a beautiful mirror. But this crystal

sheen is short-lived; a sudden breeze of wrind ends its reign ; great

damage is done to the trees by the weight of ice encrusting them,

Meteors or meteoric stones, of a most extraordinary size have been seen

falling from the atmosphere into the sea on the coast of Newfoundland2

The sparkling or phosphorescence of the waters is sometimes remarkably

beautiful in some of the deep Bays of Newfoundland.')' Newfoundland is

behind the age in not having a Meteorological Society. Such societies

are now established throughout Great Britain and Ireland, the other

British Provinces and the United States. The Board of Trade

Meteorological Department was presided over by Admiral Fitzroy, and so

perfect were the observations for detecting the approach of storms, that

information was sent daily by telegraph to the principal towns, as to

the probable weather for the next twenty-four hours. Out of nirw

warnings in 1861, only one was wrong, and that only in the direction in

which the storm came. These warnings have prevented a number of

shipwrecks, and are consequently of great commercial value to a maritime

people. Observatories ought to be established at different points of

Newfoundland, aided by the Government.

In the London Quarterly

is an article on Humboldt's Kosmos, which contains several interesting

scientific speculations. The following is a description of the wonders

of the atmosphere:—

“The atmosphere rises

above us with its cathedral dome arching toward the heavens, of which it

is the most familiar synonym and symbol. It floats around us like that

grand object which the apostle John saw in his vision, ‘a sea of glass

like unto crystal/ So massive is it that when it begins to stir it

tosses about great ships like playthings, and sweeps cities and forests

like snow-flakes to destruction before it; and yet it is so mobile that

we have lived years in it before we can be persuaded that it exists at

all, and the great bulk of mankind never realize the truth that they are

bathed in an ocean of air. Its weight is so enormous that iron shivers

before it like glass; yet a soap ball sails through it with impunity,

and the thinnest insect waves it aside with its wings. It ministers

lavishly to all the senses. We touch it not, but it touches us. Its warm

south winds bring back colour to the pale face of the invalid ; its cool

west wind refresh the fevered brow, and make the blood mantle in our

cheeks ; even its north blast braces into new vigour, and hardens the

children of our rugged climate. The eye is indebted to it for all the

magnificence of sunrise, the full brightness of midday, the chastened

radiance of the gloaming, and the clouds that cradle near the setting

sun. But for it the rainbow would want its ‘ triumphant arch,’ and the

wim|s would not send their fleecy messengers on errands round the

heavens; the cold ether would not shed snow feathers on the earth, nor

would drops of dew gather on the flowers ; the kindly rain would never

fall, nor hail storms nor fog diversify the face of the sky. Our naked

globe would turn its tanned and unshadowed forehead to the sun, and one

dreary, monotonous blaze of light and heat, dazzle and burn up all

things. Were there no atmosphere, the evening sun would in a moment set,

and without warning plunge the earth in darkness. But the air keeps in

her hand a sheath of his rays, and lets them slip but slowly through her

fingers, so that the shadows of evening are gathered by degrees, and the

flowers have time to bow their heads, and each creature space to find a

place of rest and to nestle to repose. In the morning the garish sun

would at once bound forth from the bosom of night, and blaze above the

horison; but the air watches for his coming, and sends at first but one

little ray to announce his approach, and then another, and by and by a

handful, and so gently draws aside the curtain of night, and slowly lets

the light fall on the face of the sleeping earth, till her eyelids open,

and, like man, she goeth forth again to her labour till the evening.”

GEOLOGY AND MINERALOGY.

Every stone has a

history. What says the author of the “Contemplation of Nature?” “There

is no picking up a pebble by the brook-side without finding all nature

in connection with it.” Hear, too, Lavater about a less object than a

stone: “ Every grain of sand is an immensity; ” and Shakespeare talks of

“ sermons in stones.” The study of geology opens to us a page of one of

God’s books—the book of nature, and teaches us to believe that He who

has wrought so many wonders in our globe, to fit it for man’s

habitation, will never cease to watch over man’s happiness—“will

withhold no good thing from him that walks uprightly:”

"Men’s books with heaps

of chaff are stored;

God’s book doth golden grains afford;

Then leave the chaff, and spend thy pains

In gathering up the golden grains ”

The general surface of

Newfoundland is undulating and hilly, and perhaps there is no country

whose surface bears such marks of disorder and ruin. Almost everywhere

indications of the effects of earthquakes and volcanoes are to be seen.

Immense quantities of diluvial drift are scattered in all directions

over the face of the country, consisting of gravel, and large boulders

of granite, porphyry, gritstone, slate rock, &c.

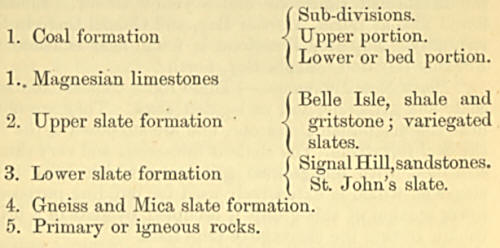

The rock formations of

Newfoundland have been arranged by Mr. Jukes into tive geological

systems, which are in the descending order, or proceeding from the newer

to the older formations, as follows :—

“The Coal Formation—The

rocks composing this formation in Newfoundland are brown, yellow, and

red sandstones; grit stones, shales, red marl, green marl and gypsum,

conglomerates, flag stones, and clunch*

“The coal of

Newfoundland is bituminous and caking, and is identical with tlie coal

of Sydney, Cape Breton. It is found on the western coast, at St.

George’s Bay, and Bay of Islands, occupying an extent of 30 by 10 miles,

and three feet in thickness.

"Gypsum, or Plaster of

Paris, is the sulphate of lime, and is part of the coal formation. It is

found in large fibrous veins passing through the marls, and also in

thick beds. It is soft, powdery, and finely laminated. Gypsum abounds in

large quantities in the cliffs of Codroy Harbour, near Cape Ray.

“Conglomerate consists

of gravel or rounded fragments of stone cemented together, which often

form rocks of great thickness and hardness. Excellent building material

of this stone was dressed during the last war, some of which are now to

be seen on Signal Hill, at St. John’s.

“Sandstone consists of

silicious sand cemented into stone, which varies in colour and hardness.

“Shah is thin layers of

clay, of different degrees of hardness and colour.

“Magnesian

Limestone.—This stone is classified as distinct from the coal formation.

The portion examined in St. G-eorge’s Ray had a thickness of fifty feet,

in beds of from two to three feet. One which was a bed of carbonate of

lime of grey colour, while the magnesian limestone had a yellow colour.

Limestone is found also at Burin, Mortier Bay, and Chapel Gove in

Conception Bay. Superior limestone is fouud near Harbour Breton, Fortune

Bay and Canada Bay, north.

“Upper Slate Formation.

— These rocks consists of -Belle Isle Slate and gritstone, and

variegated slate. They are not found near the magnesian limestone, and

are supposed to lie beneath the coal formation. The shale is micaceous

and very thin, interstratified with fine-grained gritstones, which have

a natural cleavage, which is extensively used for building purposes. The

lower portion of this group is occupied by slate of a bright-red colour,

having the cleavage of true slate.

“The Lower Slate

Formation. — These cousists of the Signal Hill sandstone, and

conglomerates with beds of light-grey gritstone, having a thickness of

800 feet, and passing down into slate rocks, which are estimated about

3,000 feet in thickness. The formation is often interspersed with white

quartz and porphyry.

“Gneiss and Mica,

Slate.—The mica slates are found interstra tified with the gneiss. Mica

slate is a mix ture of mica and quartz, and generally has a cleavage

like common slate. The walks about Newman & Co’s., premises at Gaultois

are paved with this material. Primary limestone, quartz rock, and

chlorite slate also belongs to this group. In this class of rocks

generally, organic remains first make their appearance. Mr. Jukes

discovered no organic remains, except a few imperfect vegetable

impressions in the coal.

“Primary or Igneous

Rock.—These iu Newfoundland consist of granite, serpentine, quartz,

greenstone, porphyry, sienite and traprock. These formations are

principally found on the Northern and South-west coasts. The granites

are generally newer than the gneiss and mica slate on which they repose,

and the mass of the unstratified rocks are more recent than the slate

formation. The coal formation is the newest group of rocks to be found

in Newfoundland. Of building materials, excellent fine grained granite

is obtained at St. Jacques, Fortune Bay ; at Belle Isle and Kelly’s

Islands, in Conception Bay—fine grained gritstone is obtained ;

sandstone and conglomerates are found at Signal Kill and Flat Rocks,

near St. John’s. The soft sandstones of St. George’s Bay would furnish

excellent freestone. The limestones of the various localities where they

are found, would make beautiful building stone.

“Marble of every

quality and colour can be obtained on the West Coast, fit for statuary

or any ornamental use. Excellent building stone of the porphyry and

sienite, at the head of Conception Bay could be obtained.”

Bishop Mullock, late

Roman Catholic Bishop of Newfoundland, says of this building stone :—

“We have in the

neighbourhood of Conception Bay, inexhaustible quarries of sienite or

red granite. The front of the Presentation Convent is built of this

material, and though it has not been quarried, but only taken from the

boulders on the surface, it is imperishable. In the same locality I have

seen on the road and in the garden fences the most splendid blocks of

Oriental porhyry, that rare material that we see in Rome alone, of green

serpentine and of cipollino. The traveller is astonished at the richness

of the altars in the Roman Churches, constructed in what the Italians

call pietra dura ; the brilliancy of the colour and the high polish of

the variegated material. Well, between this and Holyrood, at the head of

Conception Bay, there exist materials enough to ornament all the

churches and palaces of the world. It will, however, be long before

these rich but in-tractible materials will be turned to any account.

Grey granite is found in great abundance in almost ever locality of the

island ; slate of a superior quality in Trinity Bay, plastic clay and

brick clay abound in our immediate neighbourhood. That most useful

material, lime, is most abundant in the north and east; west, the shore

about Ferroll in the Straits of Belleisle, is almost entirely composed

of it; it is plentiful also in Canada Bay, and lately deposits have been

found in many. other places. I recently saw a quarry in the Harbour of

Burin in the side of a cliff. Codroy would furnish plaster of Paris for

all the purposes of building and agriculture, and one of the most

beautiful sea views I know of is the painted plaster cliffs near Codroy.”

Of minerals, lime,

copper, and lead are abundant. Bog iron ore is found in almost every

part of the country, and red oxide of iron is found at Ochre Pit Cove,

in Conception Bay, and iron stone in Trinity Bay. In the sand stone at

Shoal Bay, near St. John’s, a vein containing crystals of sulphuret and

green carbonate of copper, was worked in 1775, by some English miners,

but was afterwards abandoned in consequence of not paying the expense

attending the working of it. Captain Sir James Pearl, of the Royal Navy,

re-commenced the working of this mine in 1839, but his death occurring

in 1840, the work has ever since been suspended. A copper mine is said

to exist at the head of Fortune Bay.

On the western side of

the Harbour of Great St. Lawrence, in the sienite there is a vein

containing crystals of galena or lead ore, and fluate of lime,

containing silver. At Catalina, in Trinity Bay, iron pyrites are found

embedded in greywacke, or slate rock, in square pieces of from one to

three inches. These pyrites are a combination of iron and sulphur. It is

very probable that some valus able mineral springs exist at Catalina, as

mineralogist-attribute the hot temperature of almost all the hot mineral

waters to the springs running through pyrites. This mineral is also

found in other parts of Trinity Bay, at Broad Cove near St. John’s, and

other parts of the Island. At Harbour Le Cou, on the west coast, lumps

as big as a man’s head are found lying at the foot of the cliff. Pyrites

were the fire-stones of the Red Indians, from which they used to obtain

fire by striking two pieces together like flint and steel. It is said

the earlier adventurers who visited Catalina supposed the radiated

pyrites to have been gold, and that Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in 1853,

loaded his vessel with it. Springs containing a portion of iron in

solution, or Chalybeate springs, are found in various parts of

Newfoundland.

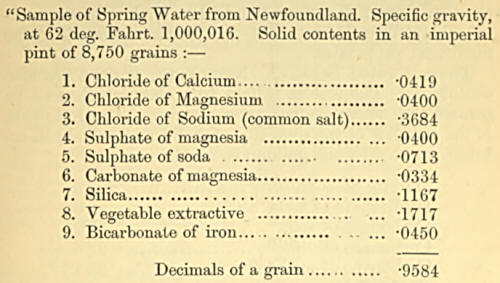

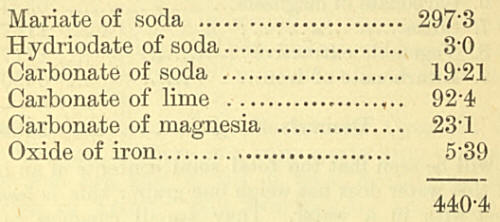

The following is an

analysis of a Chalybeate spring at Logie Bay, near St. John’s.

“It will be seen that

the total solid contents of an imperial pint of this water does not

weigh one grain : this is less than I ever met with in a water. They are

all common to spring water except the 1st, 8th, and 9th. The latter it

is which will give a character to the spring. It is chalybeate to rather

a greater extent than the waters of the “ King’s Bath,” in Bath,

England—(the King’s bath is the principal spring of the Bath waters).

The Newfoundland spring contains 45-1000ths of a grain in a pint—the

Bath spring 30-1000tlis ; and the chloride of calcium (or muriate of

lime when in the water) will contribute to the tonic effect of the iron,

while the sulphates of soda and magnesia, although not in sufficient

quantity to produce aperient effects, may prove enough to prevent the

action which chalybeates have on some constitutions. Upon the whole, I

should say that the water might be used with advantage as a general

bracer, if arrangements could be made for the accommodation of invalids

near the spring ; for it must be remembered that where iron is sustained

in water by carbonic acid, as in this case, there is always a tendency

for it to fall down as insoluble carbonate of iron, leaving the water

without its chalybeate properties.

“William Herepath,

“Mansion Rouse, Old Park, Bristol.”

The above analysis was

obtained by Captain Prescott, • the Governor of Newfoundland; Dr.

Kielley having previously informed him that the water contained some

medicinal properties.

The celebrated

Saratoga, New York, springs are also chalybeate. The waters belong to a

class which may be termed the acidulous saline chalybeate. The following

is the analysis of the quantity of solid matter held in solution by it.

In one gallon are found :—

with a minute quantity

of silica and alumina, probably 0*6 of a grain, making the solid

contents of a gallon amount to 441 grains. The gaseous contents of the

same, quality are :—carbonic acid gas, 316 cubic inches, and atmospheric

air, 4. In all, 320 cubic inches of gas in one gallon. The temperature

at the bottom of the spring is always 50°. The springs are found useful

chiefly in cases of dyspepsia, chronic rheumatism, and diseases of the

skin.

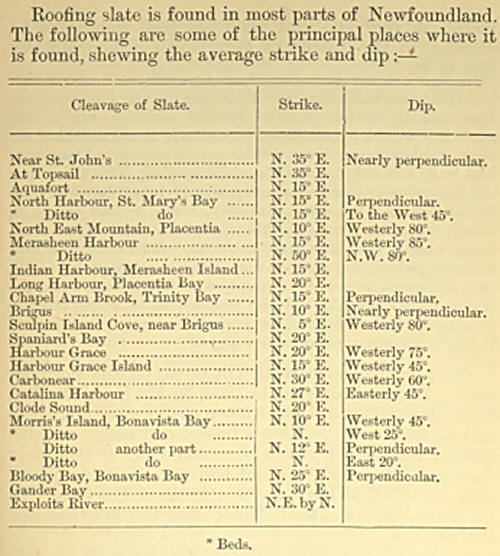

According to the

returns made to the Government in 1857, 55,000 slates, valued at

$25,000, were obtained from a quarry at the head of Trinity Bay. During

1SG9, the quantity of lead taken from this mine was 210 ton ; in 1870,

250 tons. Lead has also been discovered in Port-au-Port, on the western

shore. At the head of Conception Bay, there was shipped from Turk’s Head

Mines 20 tons, and from English head 16 tons of copper ore. The samples

of ore sent to England proved to be good specimens. A very fine lead

mine lias been worked at La Manche, in the district of Ferryland. Bishop

Mullock says of it:

“It is remarkable that

the fishermen in the lower part of Placentia Bay used to go to La Manohe,

take the pure galena, smelt it, and run jiggers out of it, and still the

existence of the mine, though almost every pebble on the shore had

specks of lead in it, was either unknown or disregarded. This shows how

much we require that the country should be explored by competent

persons. Since the discovery, three or four years ago, many thousand

pounds worth of lead has been shipped off. Once, while I was there,

sixty five tons, valued at £45 a ton, were shipped off, and another time

I saw several, perhaps 100, tons of dressed ore in barrels, prepared for

exportation ; and still so little knowledge did the people possess of

the treasure existing in their midst that for generations the only use

made of it was to dig out a bit to make a jigger.”

The principal mine is

at Tilt Cove, on the northern coast. It was discovered in 1834, by Mr.

Smith McRay. This mine yielded in 1868, 8,000 tons of copper ore, which

sold for $256,000. In 186!), a fine, vein of nickel was discovered

intersecting the copper, from which in two years ore was taken "which

realized 838,600. Another copper mine is worked at Burton’s Fund, south

of Tilt Cove. In his annual report of the Colonial Office in 1868,

Governor Hill says:—

“In the past year the

exportation of copper ore of a very superior quality was commenced, and

at this time more than 2,000 tons have been shipped. On my recent visit

to Labrador 1 stopped at Tilt Cove in Notre Dame Bay, for the purpose of

seeing a mine which is now in most successful operation, and which I

trust is only the first of many which will soon be worked with profit to

the proprietors, and great advantage to the population, in affording new

employment which is so often sorely needed in the winter season. I was

much interested in •h hat 1 witnessed. The quality of the ore is said to

be equal to the best known from any other place. The fine kinds are

worth as much as £20 per ton, and the average value of the sales of

shipments to England, is equal to about £10 per ton. Before the end of

the year, it is expected that a quantity worth from £80,000 to £100,000

will be shipped, and the ore now being extracted is even better than

that first obtained. One hundred and seventy men and boys are now on the

new pay list, and about 500 people altogether now reside at the

settlement, which was not in existence three years ago. Some of the men

make as much as £17 per month, the average being from £10 to £21.

Seventeen of the men employed, including the captain of the mine, are

Cornish miners, but the remainder are Newfoundlanders. I spoke to

several and found them well pleased with their position and

circumstances, which are indeed greatly preferable to those in which

they had frequently been placed in seasons when the fishery had been

unsuccessful, and their subsistence depended wholly on its result. If,

as I believe, will be the case in a very short time, many other mines

equally productive should be worked, it will scarcely be possible to

overvalue the beneficial effect of this new industry upon the

circumstances of the labouring population.”

It is said that Tilt

Cove mine was purchased by an English company for $75,000.

Alexander Murray, Esq.,

formerly of Sir William Logan’s staff in Canada, was employed by the

Government, to make a geological survey of the Island in 1866 and 1867,

and is still continuing it. He found a vast exposure of gypsum, between

Codroy Island and Codroy River, which may be quarried to any extent,

while the same material occurs in various parts of St. George’s Bay. He

found that the carboniferous formation of St. George’s Bay, is an

extension of the same rocks which constitute the coalfields of Cape

Breton. Mr. Murray concludes, that within the area supposed to be

underlaid by the seam coal, spoken of by Mr. Jukes, there were 54,000

chaldrons. A friend of mine in Newfoundland says :—

“Whilst the mineral and

lumbering capabilities are in their infancy—the north side of Green Bay

seems to be a deposit of copper ore—and every day new discoveries are

being made. I visited Bett’s Cove mine in the early part of September,

1876, there were 500 men at work and fifty to sixty horses, the daily

yield of ore was 140 tons, at £10 per ton. Since then mines have

commenced at Southern Arm ; Range Harbour ; and Ben-tun Pond ; at

present it is a difficulty to prognosticate what the future of this

country will be.”

Professor Selwyn says

:—

“The rule applied in

the coal-fields of South Wales, in the United Kingdom, to calculate the

productiveness of coal-seams, gives 1,000 tons for every square foot in

each acre of a seam, one foot thick, leaving a sufficient quantity for

pillars to support the roof.”

Mr. Murray says :—

“Whilst in the

neighbourhood of Port-au-Port, I was in formed that a bituminous

substance resembling petroleum had been observed on the middle Long

Point, on the west side of the Bay, and also that native copper occurred

on some parts of the main coast further north.”

Petroleum was known to

the ancient Greeks and Romans. In the Island of Zante, one of the Ionian

group, there is a spring of liquid bitumen, which has been flowing more

than two thousand years. It is said that wherever the word “pitch”

occurs in the English version of the Bible it refers to bitumen, which

was used in its natural state for many purposes. Perhaps the Ark was

“pitched” with crude petroleum. Scientists have attributed the origin of

petroleum to a variety of causes, but the most probable is that it is

the normal or primary product of the decomposition of marine animal or

vegetable organisms.

Petroleum is found in

most countries, in the stratified, and also in the volcanic and

metamorphic formations. Rock oil is found in the United States by boring

the slate and sand rocks. I think it probahle petroleum will be found

contiguous to the deposits of coal and slate of St. George’s Bay.

Mr. Murray found that

the Lauzon division of the Quebec group of rocks exists in Newfoundland,

which is the great metalliferous zone of North America.

Mr. Murray found

organic remains in several places, and also indications of gold. It is

probable gold will be found in many parts of Newfoundland, as it is not

confined to rocks of any geological period. The gold of Colorado occurs

in veins traversing crystalline rocks of oezicage, while the deposits of

North Carolina are found in paleozoic strata, similar to the Ural

Mountains and the Alps. In Nova Scotia the ore is met with in slates and

sandstones, which appear to belong to the Cambrian or Laurentian

formations, the same age being also attributed to the auriferous strata

of Australia and Wales. According to Professor Whitney, the gold bearing

quartz of California is found in the strata of the cretaceous period.

Gold is found in the aqueous and igneous rocks. It is sometimes

difficult for the inexperienced to tell the difference between yellow

mica, or iron pyrites, and gold. To detect iron pyrites it is only

necessary to pulverize the mineral and throw it upon a red-hot stove;

gold will not produce any odour or flame when tested in this way, but

the pyrites will emit fumes of sulphur. Another simple test by which

gold can be detected from iron and copper pyrites is to give a little

bit of it a hard rap with a hammer—if it be gold it will merely flatten,

but if it be pyrites it will smash into little bits; this test applies

to the smallest atom.

Yellow mica may be

easily known from gold, by its non-metallic lustre, its foliated

structure, its low specific gravity, and the harsh, scraping sound made

when a knifepoint is drawn over it. Indeed, it will crumble under the

pressure of the fingers. Gold is not acted upon by any simple acid, but

when nitric and muriatic acids are mixed they decompose each other,

producing chlorine, and a mixture of these two acids, called

nitro-muriatic acid, or aqua regia, has the power of dissolving gold.

Professor Lyon Playfair gives the following directions for examining a

mineral to ascertain whether it contains gold :—

“Supposing you have

auriferous quartz, reduce it to a powder and boil with aqua regia. After

diluting it with water, pass the solution through a filter, allow it to

cool, and add a solution of carbonate of soda until it ceases to

effervesce. Filter again, and add oxalic acid until the effervesence

ceases, and it tastes sour, then boil, and if there be any gold present

it will be precipitated as a black powder.”

The following method

for detecting gold is suggested by Professor Pepper :—

“Aqua regia, composed

of two measures of muriatic acid and one measure of nitric acid, is put

into three phials. Some tin and hydrochloric acid are placed in a fourth

phial, and some nails and sulphuric acid in a fifth. The five phials are

then arranged in a sauce-pan, and half covered with cold water. The

water is gradually heated, so as not to crack the phials. In about

half-an-hour the sauce-pan may be removed from the fire, and the

contents of each of the three phials containing mineal poured into

tumblers half full of pure rain water. To each tumbler add a portion of

the solution of tin-foil. If gold is present in any of them, a purplish

precipitate, darkening the whole fluid, is perceptible. This colour is

called the purple casius, and is used for imparting a rich ruby colour

to glass. It affords a very delicate test for the presence of gold.”

Gold has a rich, yellow

colour, is always found in metallic state, rarely pure, and has a

specific gravity of 19'5 in its most compact and pure form. The great

duc-tibility of gold is a subject of remark on the part of all writers

on the subject. The extreme maleability is well known; it has been

strikingly illustrated, by comparing the leaves into which it can be

hammered, with sheets of paper. 280,000 leaves of gold, placed upon each

other,, would be one inch in thickness; whereas the same number of

sheets of paper would extend 250 feet high. Gold has been formed into a

wire 5-0Voth part of an inch in diameter, 550 feet of which only weighed

one grain; it has also been beaten into leaves only aooooo^h of an inch

in thickness. It is said that a twenty dollar gold piece can be drawn

into a wire sufficiently long to encircle the globe.

It is said that the

entire production of the world, in 1873, was estimated at $100,000,000,

and that the total amount of gold existing in various forms in 1873,

appears to have been $4,000,000,000.

ZOOLOGY.

Of the zoology of

Newfoundland very little is known. It is a remarkable fact that neither

frogs, toads, lizards, nor snakes of any kind, have ever been found in

the country. In this respect it has been called the Ireland of America.

A distinguished Norwegian naturalist, Professor Stuwitz, spent three

years in examining the natural history of Newfoundland, where he died in

1842, while prosecuting this delightful study with intense interest.

Professor Stuwitz discovered many specimens not found in any part of

Europe. The scientific researches of this gentleman in Newfoundland

have, I believe, not yet been made public by the Norwegian Government.

The Vertebrated

Animals, forming the first division of the animal kingdom, are

distinguished by possessing an internal bony skeleton, and may be

arranged in four classes: 1st. Mammals, or those which bring forth their

young alive, and suckle them with milk ; 2nd. Birds; 3rd. Reptiles; 4th.

Fishes.

Class 1st.—Mammals.

The animals of this

class that are indigenous to Newfoundland, belong to the following

orders:—

1st.—Carnivora, or

flesh eating animals.

2nd.—Rodentia, or gnawing animals.

3rd.—Ruminantia, or ruminating animals.

4th.—Cetacea, the whale tribe.

Order 1.—Carniva.

The common rat and

field mouse are found infesting every place. The Bat (vespepertilio

primosus) is small, and is occasionally, in the evenings, seen skimming

the air on leathern wings, in search of insects on which it principally

preys. The Black Bear (Ursus Americanns). This quadruped passes the

winter in a state of torpour, concealed in the woods. In the summer it

chiefly subsists on roots and berries. Several of these animals are

killed on the northern coast during the spring and summer. These animals

are of a ferocious disposition, but when taken young are, to a certain

extent, tamed. Young ones are sometimes brought to St. John s from the

northward. The Weasel (JMustela Martes) in summer is brown, but in

winter turns white. The Marten or Wood-cat (Mustela Martes).— Formerly

great numbers of these animals were killed by the Indians, but they are

now seldom met with. The Otter (.Lutra Canadensis) has been so much

sought after, for the value of the fur, that it is now become

comparatively scarce in the country. The most formidable animal in

Newfoundland is the

Wolf (Cani\s Lupus

Americanis). In some parts of the island they prove destructive to the

cattle.

The Rev. B. Smith, of

Trinity, gives the following account of the narrow escape of one of his

people from wolves, in his report to the Society for the Propagation of

the Gospel, in London, in 1857:—

“He had gone in his

punt to a point about a mile from his house, to cut firewood, and when

returning with his load of sticks, at a short distance from the shore,

he heard a howling, which at first he did not understand; hut after

going a little farther, on looking round he saw the animals, at some

distance, in full cry towards him. He threw down his load and ran to his

punt, which was fortunately moored but loosely by the painter thrown

round a rock. In his haste he caught up the rope, and leaped into the

punt, which, with his motion, bounded off; and by the time he had

distanced the shore some twenty yards, the ravenous creatures reached

the water, and, disappointed of their prey, were howling and foaming at

the mouth hideously. He had no guu or other weapon, and was overpowered

with emotion for his narrow escape.”

A few years ago these

animals were rather numerous in the neighbourhood of St. Johns, prowling

about so near the dwellings as to endanger the lives of the inhabitants.

An Act was passed by

the Local Government entitled,

“The Wolf-killing Act,”

under the provisions of which every person killing a wolf, on the

presentation of the head and skin, was to receive a reward of five

pounds. About eight or ten wolves were annually killed on the northern

and western coasts. In proportion as the popu- . lation increases, so

will the monarch of the Newfoundland forest disappear, until at length,

as in England and Ireland, its existence will be no longer known. The

history of almost every nation furnishes us with proofs, that in the

same ratio as the empire 6f man has been enlarged, so has the animal

kingdom been invaded and desolated. The history of Newfoundland bears

evidence, that some of the tenants of the ocean and of the feather

tribes, have become extinct by the agency of the destroying hand of man.

The Newfoundland dogs,

for the most part, are poor spurious descendants of the once noble race.

Those fine samples of the race to be met with in the United States, are

rarely found in Newfoundland. No animal in Newfoundland is a greater

sufferer from man than the dog. This animal is employed during the

winter season in drawing timber from the woods, and he supplies the

place of a horse in the performance of several offices. I have

frequently seen one of these creatures drawing three seals (about one

hundred and thirty pounds weight), for a distance of four miles, over

huge rugged masses of ice, safe to land. In drawing wood, the poor

animal is frequently burdened beyond his strength, and compelled to

proceed by the most barbarous treatment. My friend T. Drew, Esq., one of

the editors of the Spy and Christian Citizen, published at Worcester,

Mass., United States, relates the following instance of the sagacity of

the Newfoundland dog, which was communicated to him by a female friend

of his, who had been spending the summer of 1850, at Halifax, N. S.:—

“Tige is a splendid

Newfoundland, and possesses good sense as well as good looks. He is in

the habit of going every morning with a penny in his mouth, to tlie same

butcher’s shop, and purchasing his own breakfast, like a gentlemanly dog

as he is. But it so happened upon one cold morning, during the past

winter, the shop was closed, and the necessity seemed to be imposed upon

Tige, either to wait for the butcher’s return, or look for his breakfast

elsewhere. Hunger probably constrained him to take the latter

alternative, and off he started for another butcher’s shop, nearest to

his favourite place of resort. Arriving there, he deposited his money

upon the block, and smacked liis chops for breakfast as usual; but the

butcher, instead of meeting the demand of his customer as a gentleman

ought, brushed the coin into his till, and drove the dog out of the

shop. Such a disgraceful proceeding on the part of a man, wy naturally

rullied the temper of the brute ; bnt as there was no other alternative,

he was obliged to submit. The next morning, however, when his master

furnished him with the coin for the purchase of breakfast, as usual, the

dog instead of going to the shop where he had been accustomed to trade,

went immediately to the shop from whence he was so unceremoniously

ejected the day before —laid his penny upon the block, and with a growl,

as much as to say, ‘ you don’t play any more tricks upon travellers,’

placed his paw npon the penny. The butcher, not liking to risk, under

such a demonstration, the perpetration of another fraud, immediately

rendered him the quid pro quo, in the shape of a slice of meat, and was

about to appropriate the penny as he had done the day previous, to his

own coffers; but the dog, quicker than he was, made away with the meat

at one swallow, and seizing the penny again in his mouth, made off to

the shop of his more honest acquaintance, and by the purchase of a

double breakfast, made up for his previous fast.”

The species of fox

usually taken in Newfoundland are, the common red or yellow fox (Canis

Fulvus); and the patch or cross fox (Canis Decussatus) ; the black or

silver fox (Canis Argentatus) being seldom seen.

The kind of seals most

plentiful passing along the Coast of Newfoundland with the field-ice,

are the harps, or halfmoon seals, (phoca Groenlandica). About the latter

end of the month of February these seals whelp, and in the northern seas

deposit millions of their young on the glittering surface of the frozen

deep ; at this period, they are covered with a coat of white fur,

slightly tinged with yellow. I have seen these beautiful “ white coats ”

lying six and eight on a pan of ice, resembling so many lambs, enjoying

the solar rays. These animals grow very rapidly, and in about three

weeks after their birth begin to cast their white coats; they are now

easily caught, being killed by a slight stroke across the nose with a

bat or gaff* At this time they are in prime condition, the fat being in

greater quantity, and containing purer oil than at a later period of

their growth.

It appears to be

necessary to their existence, that they should pass a considerable time

in repose, on the ice ; and, during this state of helplessness, we see

the goodness of

Providence in providing

these amphibious creatures with a thick coat of fur, and a superabundant

supply of fat, a defence against the chilling effects of the ice, and

the northern blasts. Sometimes, however, numbers of them are found

frozen in the ice; these “ cats ” are highly prized by the seal-hunters,

as the skin, when dressed, makes excellent caps for them to wear while

engaged in this perilous and dangerous voyage. At one year old, these

seals are called “ bedlamers;” the female is without dark spots on the

back which form the harp; and the male does not show this mark until two

years old. The voice of the seal resembles that of the dog, and when a

vessel is in the midst of myriads of these creatures, their barking and

howling sounds like that of so many dogs, causing such a noise, as in

some instances to drive away sleep during the night. The general

appearance of the seal is not unlike the dog; hence some have applied to

the seal the name of sea-dog, sea-wolf, &c. These seals seldom bring

forth more than one, and never more than two, at a litter. They are said

to live to a great age. A respectable individual informed me that he saw

a seal which was caught in a net; it was reduced to a mere skeleton,

consisting of nothing but skin and bone; the teeth were all gone, and

its colour a white grey, which he attributed to old age. Buffon, the

French naturalist, says :—

“I am of opinion that

these animals live upwards of a hundred years, for we know that

cetaceous animals in general live much longer than quadrupeds ; and as

the seal fills up the chasm between the one and the other, it must

participate of the nature of the former, and, consequently, live much

longer than the latter.”

The hooded seal (phoca

cristata) is so called from a piece of loose skin on the head, which can

be inflated at pleasure, and when menaced or attacked this hood is drawn

over the face and eyes as a defence from injury, at which time the

nostrils become distended, appearing like bladders; the female is not

provided with this hood. An old dog-hood is a very formidable animal;

the male and female are generally found together, and if the female

happens to be killed first the male becomes furious; sometimes it has

taken fifteen or twenty men hours to despatch one of them. I have known

a half-dozen handspikes to have been worn out by endeavouring to kill

one of these dog-hoods; they will snap off the handles of the gaffs as

if they were cabbage-stumps; and they frequently attack their

assailants. When they inflate their hoods it seems almost impossible to

kill one of them; shot does not penetrate the hood. Unless the animal

can be hit somewhere about the side of the head, it is almost a hopeless

task to attempt to kill him. These animals are very large; some of their

pelts which I measured were from fourteen to eighteen feet in length.

The young hoods are called “ blue backs ; ” their fat is not so thick

nor so pure as the harps, but their skins are of more value ; they also

breed further to the north than the harps, and are generally found in

great numbers on the outer edge of the ice ; they are said not to be so

plentiful, and to cast their young a few weeks later than the harps. The

square fipper, which is, perhaps, the great seal of Greenland (phoca

barbata), although there it does not attain to so large a size as the

hooded seal, while in Newfoundland it is much larger, is now seldom

seen, The walrus (tricheens ro&marus), sometimes called sea-horse,

sea-cow, and the morse, is now seldom met with; formerly this species of

seal was frequently captured on the ice. This animal is said to resemble

the seal in its body and limbs, though different in the form of its

head, which is armed with two tusks, sometimes twenty-four inches long;

in this respect much like an elephant. The under jaw is not provided

with any cutting or canine teeth, and is compressed to afford room for

these enormous tusks, projecting downwards from the upper jaw. It is a

very large animal, sometimes twenty feet long, and weighing from 500 to

1,000 pounds; its skin is very thick and covered with yellowish brown

hairs.

The harbour seal (phoca

vitulema), frequents the harbours of Newfoundland summer and winter.

Numbers are taken during the winter in seal nets. The Newfoundland seals

probably visit the Irish coasts. Mr. Evans, of Darley Abbey, near Derby,

gives an account of a number of seals killed on the west coast of

Ireland in 1856 ; amongst them an old harp. Sir William Logan discovered

the skeletons of whales and seals near Montreal.

The white, or polar,

bear (ursus maritimus) is sometimes seen on the coast, regardless of the

ocean storm and the intense cold. This animal roams among the rifted ice

in search of food. A few years ago, one of these animals was killed near

St. John’s. It seldom, however, travels in the woods more than a mile or

two, and then only by accident, arising, perhaps, from the

inconveniences of the weather.

Order 2.—Rodentia.

The Beaver (Castor

Fiber, Americanus), once so abundant in Newfoundland, is now scarce. An

account of the ingenuity of the beaver in building his house, is given

in almost every book of natural history. The Musk Rat or Musquash, (Aviola

Hibethicus) is plentiful in Newfoundland, and its flesh is frequently

eaten. The Hare (Lepus A'ttiericanus) is to be found in great numbers,

on the west and northern coasts of Newfoundland. They are white in

winter, but turn brown in summer. The American Rabbit is not found in

Newfoundland.

Order 3.—Rwminantia.

The Cariboo or

Reindeer, (Cervus Tarandus). On the western coast of Newfoundland, these

are found in droves of from two to three thousand. Great numbers are

killed. The red Indians used to have fences 30 miles long for entrapping

the deer. They are also abundant on the northern coast, during the

summer season. It is very probable that the reindeer of Newfoundland

could be domesticated, and, as in Lapland, be useful to man. Of the

Lapland deer, it has been said:—

“The foot and eye of

this creature are beautifully adapted to the country it is destined to

inhabit. The hoof is very widely cloven, and when pressed on the ground

the two parts expand, thus forming a broad surface, and preventing it

from sinking in the snow, amidst which it spends a greater portion of

its life. On the foot being raised, the divisions again fall together,

making a curious crackling noise, resembling repeated electric shocks.

Besides the usual eyelids, he is provided with a nictitating membrane

extending over the eyes, through which, in snow storms, he can see

without exposing those delicate organs to any injury.”

White, in his “Natural

History of Selborne” says :—

“There is a curious

fact not generally known, which is, that at one period the horns of

stags grew into a much greater number of ramifications than at the

present day. Some have supposed this to have arisen from the greater

abundance of food, and from the animal having more repose, before

population became so dense. In some instances these multiplied to an

extraordinary extent. There is one in the Museum of Hesse Cassel, with

twenty-eight antlers. Baron Cuvier mentions one with sixty-six, or

thirty-three on each horn. If you would procure the head of a fallow

deer, and have it dissected, you would find it provided with two

spiracula, or breathing places, besides the nostrils, probably analogous

to the puncta lachrymalia in the human head. When deer are thirsty, they

plunge their noses, like some horses, very deep under water, while in

the act of drinking, and continue them in that position for a

considerable time, but to obviate any inconvenience, they can open two

vents, one at the inner corner of each eye, having a communication with

the nose. Here seems to be an extraordinary provision of nature worthy

of our attention, and which has not that I know of been noticed by any

naturalist \ for it looks as if these creatures would not be suffocated,

though both their EE mouths and nostrils were stopped. This curious

formation of the head may be of singular service to the beasts of chase,

by affording them free respiration, and no doubt these additional

nostrils are thrown open when they are hard run.”

Order 4.—Cetacea.

The Whale tribe, though

called fishes, are true mammalia, producing from one to two cubs at a

time, which are suckled in the .same manner as land animals. The kind

appearing on the Newfoundland coast, is the sharp-nosed whale {Balaena

Acuto Rostra). Pike-headed species (Ba laena Boops). The kind most

plentiful is the fin-backed whale (Balaenoptera Jubartes), which lives

on capelin, lance, &c. No less than fifty of these are sometimes seen

spouting at one time. The great Greenland whale (Balaena Mysticetus) is

occasionally seen oh the coast. Probably the whole tribe of whales

frequenting the Greenland seas, sometimes visit the Newfoundland coast.

Great numbers of what some call Black-fish, and others Pot-heads, are

killed during the autumn along the shores. They are of the species (Delphinus

Dephis); the colour of the whole body is a bluish black, except a

portion of the under part which is bluish white, the head is round and

blunt, and the blow-liole very large. They are from sixteen to

twenty-five feet in length, with a forked tail. The fat is from one to

three inches thick, and they each yield from SO to TOO gallons of oil.

The Porpoise (Delphinus

Phoceana Communis) is plentiful in Newfoundland. Its length is from four

to six feet; the colour of the back is bluish-black, the sides grey, and

the under part white. The flesh is considered a sumptuous article of

food.

The Sword-fish (Dephinus

Gladiator) or grampus, is an untiring persecutor of the smaller whales.

Class II.—Birds.

These consist of six

orders, as follows :—

1st.—Raptor es, or

birds of prey.

2nd.—Insessores, or perching birds.

3rd.—Scansores, or climbing birds.

4th.—Rasores, or scraping birds.

5th.—Orallatores, or wading birds.

6th.—Natatores or Palmipedes, swimming or webfooted.

Order 1st.—Raptores.

The Sea Eagle (Falco

ossifragus) is occasionally seen. The Fish Hawks are plentiful on the

coast of Newfoundland ; also the Sparrow Hawk and Pigeon Hawk (Falco

Columbarius). Of owls there are great numbers and varieties. The Snow

Owl (Strix Nyetea) is plentiful on the northen coast, where great

numbers are killed. The flesh is considered delicious.

Order 2nd.—Insessores.

The Shrike, or

Butcher-bird (Lanicus Collurio) is sometimes seen. The Crow (Corvus

Corone) is found all over the country. The American Robin, or Thrush of

Pennant (Turdus Migrator us), called the Blackbird in Newfoundland,

generally appears about the beginning of May, and often, while the

ground is covered with snow, they congregate in flocks on some garden

fence and pour forth their wild and sonorous notes. They are the

best-known and earliest songsters of Newfoundland. They are very

plentiful, and during the spring great numbers are killed for table use.

The Snow Buntings (Emberiza Nivalis) are to be seen in flocks dressed in

their silvery plumage, hopping about the snow ; also the fine grosbeak (Loxia

Enuclea-tor), which is one of the handsomest birds which visits

Newfoundland. They, with the Crossbill (Curvirostra Americana), are,

however, seldom seen. The little black-capped Titmouse (Paras

Artrieapillus) is seen enjoying the summer sun and braving the winter

storm. Tlie Jay (Corvus Canadensis) is mostly found in the thick woods.

The earliest warbler that visits Newfoundland is the Sparrow (.Fingilla

Nivalis), called in America snow-bird, and known by its single “ chip.”

The white-throat sparrow (Fingilla Albicollis) and the fox-coloured (Fingilla

Rufa) are plentiful. The Swallows (Hirundiniedce). Of this family there

are several varieties ; the most plentiful is the Sand Martin (Ilirundo

Ripariu). The Night Hawk is occasionally seen.

Order 3rd.—Scansures.

Of Woodpeckers, there

are several kinds, the threetoed (Ficus Trydactylus) are the most

abundant.

Order 4th —Rasores.

This order includes the

Peacock, Turkey, and domestic fowls. “White’s Natural History of Selbome,”

says:—

The pied and mottled

colours of domesticated animals are supposed to be owing to high,

various and unusual food. Food, climate, and domestication, have a great

influence in changing the colour of animals. Hence the varied plumage of

almost all our domestic birds. In a wild state, the dark colour of most

birds is a safe guard to them against their enemies. Natural ists

suppose that this is the reason why birds which have a very varied

plumage, seldom assume their gay attire, until the second or third year,

when they have acquired cunning and strength to avoid their enemies. A

few years ago I saw a cock bullfinch in a cage which had been caught in

the fields after it was come to its full colours. In about a year it

began to look dingy, and blackening every succeeding year until at the

end of four years it was coal black. Its chief food was hempseed. Such

influence has food on the colour of animals.”

The Ptarmigan or Grouse

(Tetras Lag(ypus), called in Newfoundland, partridge, are plentiful.

They are white in winter, and of a reddish brown in summer.

Order 5th.—Grallatores.

The Snipe (Scolopax

Gallinago) is found in all parts of the country. The Beach Bird (Tringu

Hypolareus) and other Sandpipers are abundant.

Curlew (Americanus) and

Plover (Charadius), are found in great numbers on the northern coast.

The Bittern (Ardea

Minor) is only occasionally seen.

Order 6th.—Natatores.

The Goose (Anser

Canadensis), and the Common Wild Goose (Anas Anser), with other species

are found in Newfoundland. Of Ducks there are several varieties, among

which are the Black Duck or Mallard (Anas Bosehas), and (Anas Marila)

fresh-water Duck, also the Eider Duck (Avas Mollissima). The Sheil-drake

(Anas Tadoma), the Long Tailed Duck and the Teal (Anas Cressa). The

common Tarn or Sea-swallow (Sterna Hemndo), is plentiful. Of Gulls,

there are a great variety. The Wagel or Great Grey Gull (Larus Naocius),

the Arctic Gull (Larus Parasiticus), the Common Gull (Larus Canus), and

many others. The Stormy Petrel, or “ Mother Cary’s Chickens” (Procellaridce

Pelagica), breed in great numbers on the rocky lonely islands of the

northern coast.4

The Gannet or Solan

Goose (Pelicanus Bassamus). and the Cormorant (Pelicanus Carbo), are

found on all parts of the coast. The Loo, Loon, or great Northern Diver

(Colymbus Glacialis), is occasionally seen.

Puffins (Alca Arctica)

are abundant*. The furs or merrs (Colymbus Triole) are generally called

by the inhabitants of the east “Bascalao birds.” They breed in great

numbers on the islands of Basalao and Funk. They make no nests, and lay

their eggs, which are pyriform, of a greenish colour and great size, on

the bare rock. Great quantities of eggs are taken from these islands in

the month of June by the fishermen. The penguin, or great auk (A lea

Impennis, Linn.), about seventy years ago, was very plentiful on Funk

Island, but has now totally disappeared from the coast of Newfoundland.

Incredible numbers of these birds were killed, their flesh being savoury

food, and their feathers valuable. Heaps of them were burnt as fuel, to

warm the water to pick off the feathers, there being no wood on the

island. The merchants of Bonavista at one time used to sell these birds

to th poor people by the hundred-weight, instead of pork. It was thought

that guano might be found on Funk Island. I procured a sample of what

was supposed to be the birds’ dung, but it proved to be nothing more

than bones and turf. There are islands on the northern and western

coasts of Newfoundland called the Penguin Islands, so named, probably,

from the number of penguins at one time breeding on them. The penguin is

from the size of a goose to double as large; its wings are short,

resembling the flippers of the seal, and its feet broad and webbed. It