|

"Is not this the fast

that I have chosen? to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy

burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every

yoke?” Isa. lviii. 6.

“A little before winter

set in, I went to Merigomish, a small settlement about ten miles, or

rather fifteen miles, east from Pictou, in consequence of an invitation,

preached to them on Sabbath, and visited several of the families. Having

no prospect of a minister themselves, they begged of me to visit them as

often as I could, and, as far as depended upon them, they put themselves

under my charge. I promised to do for them what I could, and accordingly

I gave them annually less or more supply for nearly thirty years, when

they got a minister to themselves—the Rev. William Patrick. This

application from without the bounds of my own congregation was some

consolation to me. Indeed, I might be called the minister of the north

coast of Nova Scotia, rather than of Pictou, for at that time there was

no other minister along the whole north coast, except one Church of

England clergyman near the east end of the Province.”

Among the first

settlers in Merigomish were some of the Hector’s passengers, but the

greater part of them were disbanded soldiers. From this it may be

understood that they were neither so steady in their habits, nor so

attentive to the duties of morality and religion as the people in the

other sections of the county. In fact they were an extremely wild set.

In particular, drinking

prevailed to an extent which is now almost incredible. An amusing

anecdote is told illustrative of this. On going there once to preach, a

man applied to him to baptize a child for him. Before consenting, the

Doctor made some enquiries among some of his neighbours as to his moral

character. He received the most ample testimonials as to* his good

conduct. “But,” said the Doctor, “does he not drink? I have heard that

he sometimes takes a spree.” “Oh yes,” was the reply, “but we all do

that.” Until the arrival of a second minister in the county, the Doctor

could only give them occasional sermons, but after that event, they

became part of his regular charge, and received a fifth of his services,

until the increase of the other sections of his congregation obliged him

to relinquish the care of them. They were then for several years vacant,

receiving occasional sermons from him and other members of Presbytery,

until the settlement of Mr. Patrick in 1815. His labours among them were

successful, so that a great change took place in the habits and morals

of the community. Yet owing we suppose to the partial ministerial

service he was able to give them, and the strength and inveteracy of

their old evil habits, the change was not so complete as in other

sections, nor did the people for a long time seem as thoroughly imbued

with the spirit of religion as the inhabitants of other portions of the

county.

“In November I received

the first money for preaching in Pictou—a part of the first year’s

stipend. I lived a year and a quarter here without receiving a shilling,

and almost without giving any. I ought to have received forty pounds of

cash for the preceding year (with forty pounds worth of produce), but

twenty-seven was all that I received. The truth is, it could not be

gotten. The price of wheat was then six shillings, and some of the

people offered wheat for three shillings, to make up their share of the

stipend, but could not obtain it. Almost all the twenty-seven pounds

were due by me to some necessary engagements of charity which I was

under. My board, which was my chief expense, was paid from the produce

part of the stipend, winch was not so difficult to be obtained as the

cash part. But even of the produce part there was nigh ten pounds

deficient.

“I plainly saw that I

need never expect my stipend to be punctually paid; indeed, scarcely

anything is punctually paid in this part of the world. It is a bad

habit, ill to forego. But my mind was so knit to them, by the hope of

doing good to their souls, that I resolved to be content with what they

could give. Little did I then think that I would see the day that Pictou

would pay £1,000 per annum to support the gospel. I suppose I have lost

£1,000 in stipends; but I have now ten times more property than when 1

came to Pictou.”

We must here give some

account of the payment of stipend at that time, and during almost the

whole course of his ministry. Iu the first place, the mode of raising

the amount was by assessment. How it was for the first year or two we

are uncertain, but from an early period this plan was adopted under the

following pledge:

“We promise to pay to

James MacGregor, minister, one hundred pounds currency yearly, one half

in cash and one half in produce, as wheat, oats, butter, pork, viz., on

the first Tuesday of March, yearly. And we hereby agree that there be a

yearly Congregational meeting on the second Tuesday of July, to assess

for and collect the stipends, as we are all to pay in proportion to our

polls and estates. We agree that there be four or five assessors and

collectors.”

And the following bond

of adherence was subscribed by those who bad not been parties to the

original call:

“We the underwritten

hereby declare our adherence to the obligation subscribed by the older

settlers of this river for paying the minister’s stipend, that is,

conjointly with the former subscribers, we promise to pay to James

MacGregor, the sum of one hundred pounds yearly, one half in cash, one

half in produce, as wheat, oats, butter, pork, on the first Tuesday of

31 arc h yearly, by an equal assessment upon our polls and estates.

"Witness our hands this

sixteenth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and three, at the

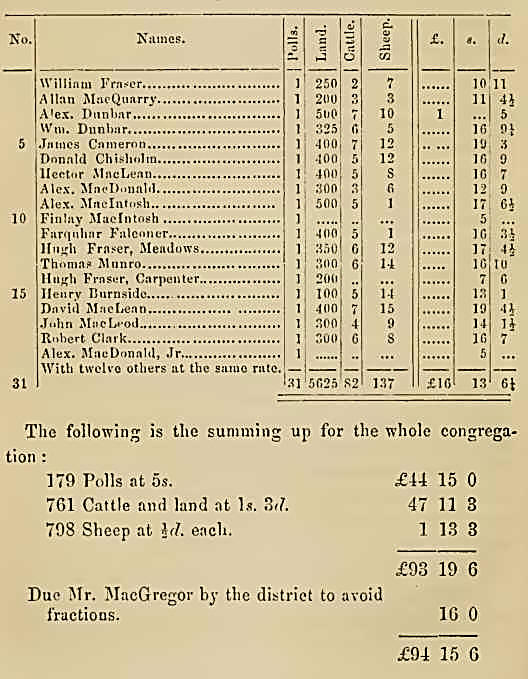

East River of Pictou.” The assessment was made on their land, cattle,

and polls, or adult male heads, one for example being at the following

rate: Polls, 5s. each, cattle, Is. 8d., sheep, 1s., each hundred acres

of land, 1s. 3d. We will give a specimen of one of the assess bills, as

we think it will be deemed a curiosity iu the present day.

“Assess Bill of the

Minister’s Stipend from 81st July 1S03, to the 31st July 1S04. West

Branch.”

In making these

assessments there was sometimes difficulty in adjusting the proportion

due by the different sections. This we have on the back of the assess

bills, such notes as the following, “East River, Pictou, June 1st,

1801:—Sir, I made the Sess-Bill long ago, but the upper part of the

Settlement says, they will not pay you till they get better convenience

of the sermon, and I did not send it down till now, and you will excuse

me;—Your humble Servaut, I. C.” “And again, I, H. F., have assessed all

them that is above Angus MacQuarry, and we want our share of the sermons

at Charles Macintosh’s, as we will pay, till such time as we will agree

about the meetinghouse.”

The plan of raising the

stipends by assessment was liable to objection, and in practice attended

with a number of difficulties. Accordingly, in the year 1807 an attempt

was made to raise the minister’s stipend by voluntary subscription under

the following heading:—

“The manner of raising

the minister’s stipend by assessment being attended by several

inconveniences, and it being thought probable, that it may be more

conveniently raised by subscription, we, the subscribers, in order to

make a fair trial, which of the two ways is best, have agreed to a

subscription for three years. Wherefore we promise to pay or cause to be

paid yearly, for three years, to the Rev. James MacGregor for his

ministerial labours, the sums annexed to each of our names respectively

at his house, on the first Tuesday of March, one-half in cash, and

one-half in merchantable produce, at market price. Done at Pictou,

October 26th, 1807.”

The result of this

effort was a subscription on the Upper Settlement, East River, of

£56.0.2, and on the Lower Settlement of £56.19.0. But assessments were

resumed as early as the year 1810. In the year I815, however, the system

of voluntary subscription was at length finally adopted under the

following heading :—

“On account of the

complaints and difficulties attending assessment, the Congregational

meeting in July last resolved to raise the minister’s stipend by

voluntary subscription, the subscription to be reduced or changed after

three years, as the Congregational meeting shall direct. Of the half

belonging to the (Upper) Settlements, amounting to seventy-five pounds

currency, we, subscribers, promise to pay our shares annually, for three

years, on the first Tuesday of March, to the Rev James MacGregor, for

his ministerial labours among us, viz., the sums annexed to our names.

N. B.—It was agreed by the Congregational meeting, that if the

subscription should amount to more than seventy-five pounds, the

overplus shall be deducted from the sums of those who subscribe highest,

according to their circumstances, as the men appointed for that purpose

shall decide. The sermons at the East and West Branch meeting houses

shall be in proportion to the subscription belonging to each, March 1st,

1815.”

Such were the plans

adopted for raising the amount. With these there was not so much reason

to complain, but in every other respects, the arrangements were most

deficient. During the greater part of his ministry the amount promised

was entirely inadequate, even if it had been regularly and fully paid.

After the breaking out of the war the prices of almost every article

were very high, flour being often as high as five pounds per barrel, and

upwards, and yet his salary for a long time was only £100 currency,

$400. Even if this amount had been regularly and punctually paid, it

would have been entirely insufficient for his comfortable maintenance,

but this was very far from being the case. There were no regular times

of payment observed. There were dates fixed at which the amount ought to

be paid, but nobody thought the worse of himself, if he were weeks and

eveu months behind the tiiue. Ilis first year had expired in July, yet

it was November before any part of the salary was paid, and though their

arrangements were not always so bad, and though there were always

individuals who paid with some regard to the stated times appointed, yet

more or less of this irregularity continued till the end of his life.

But the deficiencies

were no less remarkable as to the amount. There was no sense of joint

responsibility, except in the apportioning of the amount among the

different sections of the congregation. As a congregation they did not

feel any obligation to raise a fixed sum, but each man thought he had

done remarkably well, if he had paid the amount of his own assessment.

Thus he received the contributions of good payers, but those of the bad

he bad to lose altogether. It must be observed that the large majority

of his congregation were Highlanders, who are said “to have a decided

preference for gratis preaching.” They had generally belonged to the

Established Church in Scotland, where they had not been accustomed

directly to contribute to the support of the gospel, and thus they were

wanting to some extent in the inclination, and entirely in the habit of

discharging that duty. Besides a large proportion of his flock continued

to be new settlers, who had not the ability to pay if they were ever so

willing. In this way a large amount was lost entirely. On the first year

when the salary was only eighty pounds nominally, there were ten pounds

short of the produce part and thirteen of the cash. The same thing

continued every year. Among his accounts we find such entries as the

following, regarding individual subscriptions. “A Mak. owes 14s, am

willing to forgive.” “All due by former lists and more, but I forgive

it.” “'With 6s. 8d., perhaps to be forgiven.” “I forgive 6s. 11d” “Paid,

that is, forgiven.” In this way he might well say that he had lost

upwards of £1000 of stipends.

In regard to the

collecting the stipend, another circumstance must be mentioned, that

during the principal part of his ministry the greater part of the

accounts for stipend were kept by himself. During the first few years

they were kept by the late John Patterson thus far, that a good

proportion of the produce contributions were paid into his hands, and he

sent them to market, or otherwise disposed of them, supplying the

Doctor, in return, with goods or it might be some cash. But after his

marriage, all accounts were kept by himself. If there were such officers

as collectors or committee of management, it was but little they did,

for he had still to deal with every individual contributor in his

congregation. This involved a great amount of trouble, rendering it

necessary that he should keep accounts with one or two hundred

individuals, for sums from 5s. upwards, and receiving payments in a

quarter of veal from one, a cake of maple-sugar from a second, or a

bushel of wheat from a third.

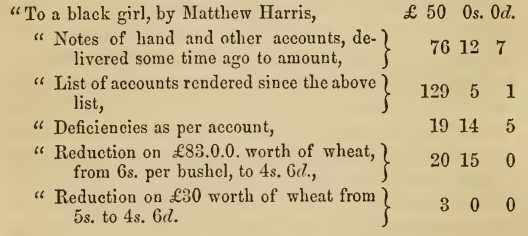

We have before us John

Patterson’s account up till the time of his marriage ; nine years after

his arrival, and a few of the charges are curious. Witness the following

items, with the exception of the first, all at the close of the account:

Some of our readers may

have heard of stipend being paid in some curious ways, but we arc

certain that the first item in the above list will be something new to

them, at least as occurring this side of Mason & Dixon’s line. We shall

have some explanations to give regarding it presently. In this account

wc must notice the large deficiencies, not only the amount stated as

such, but also the large amount of accounts and notes of hand, amounting

to over £200, the greater part of which we may safely presume was never

paid.

Then the real value of

the produce part of the payments was far short of the nominal. This

appears on the above, where there appears a discount of nearly 25 per

eent, on that portion of the payments. We have before us piles of his

accounts, which are full of such credits as the following :—(C. M‘K.

10Jibs, tallow.” “P. G., 3 bushels of wheat.” “I. T., 2s. Gd. in birds,

and 131bs. in butter, and 191bs. sugar.” “ D. F., 26£ weight of butter;

gave him a Gaelic Bible.” “P. F., paid in 1787, dogs,1

6s.; 1788, cash, Gs.; 1789, wheat, 11s. 6d.” W. owes paid by a sheep,”

while another has the following credit, u paid two brooms.” Now, while

many such payments were the full money value, at which they were

estimated, yet many others were far from being so, and on the whole such

a mode of payment was far from equal to cash. Often an inferior article

was brought, an article which was unsaleable in the owner’s hands,—at a

time when the minister did not need it, or could not convert it into a

profitable use,—and yet he was expected to take it as a matter of

course, and not only so, but to allow for it the highest price. He could

not say much about its quality, or refuse it altogether, or chaffer

about the price, without the risk of giving a serious affront. And the

length to which some would go in taking advantage of him may appear in

such credits, as the following, “121bs. ram-mutton,” or “361bs.

beech-pork.”

When all other means

failed, persons had an easy and never failing resource, viz., giving

their notes. Such was the credit system then prevailing, that persons

actually considered, that they had paid their accounts, when they had

given their notes. A person once meeting another asked him where he had

been. “Oh, I have been up at Mr. Mortimer's, paying my account.”

“Indeed, how did you pay it?” “I gave him my note.” In the lists of

arrears we find a number marked “paid by note.”

Few of these would be

paid. A person has told me that he has seen him looking over his old

papers, and as he came across such notes quietly putting them into the

fire.

Though these notes were

legal obligations, it would never have answered for him to enforce them

by the civil law. We may mention here that many years afterwards an

attempt was made to force payments for the minister’s salary—not by

himself, for he would rather have lost all, than have pressed any

person, but by the collectors on his behalf. For the honour of the

voluntary principle, it may be mentioned that the effort was attended

with most injurious consequences. Not only did the man who was

prosecuted become his most determined enemy, but it lost him, for a time

at least, one of his staunchest supporters. When the man was sued he

came with a poor story to the Doctor, who with his usual kindness

forgave the amount, and at his request gave him a receipt. The Doctor

enjoined him to show this without delay to the collector, who had taken

out the writ against him, in order that the process might be stopped.

Instead of doing this, the man kept the receipt until the day of trial,

and then after the collector had stated the case, produced the receipt.

It was natural enough that the collector should feel annoyed, but being

a man of high temper, though a great friend of the Doctor’s, he was

highly indignant at him, although he was perfectly innocent in the

matter, and it was some time, notwithstanding all the explanations he

received, before his wrath was averted. It may be mentioned that the

whole question of prosecuting for ministers’ stipend was tried in

another case before the courts of law, when it was found that the laws

of the Province did not sustain the practice, in reference to dissenters

from the Church of England.

As we have referred to

the modes of paying ministers’ salary, it is but just to remark, that

the whole business of the country was at that time conducted in a

similar manner. The system of credit universally prevailed, and there

were no regular times of payment. This continued for many years, even

when money became abundant, and, strange to say ! all parties loved to

have it so. The purchasers hesitated not to take goods freely, the day

of payment being so far off, they felt as if they were getting them

without paying for them. It seemed so easy a way of getting what they

wanted, that any system of ready payment they would have regarded as

harsh and cruel. On the other hand, traders actually encouraged people

to go in debt, either for the sake of retaining their custom, or the

power which it enabled them to exercise over them. The credit system

would not have been so bad if there had been regular times of

settlement. But so far from this being the case, it was often difficult

to get an account from the merchant, particularly if he thought it was

to be settled. lie considered it his interest to keep persons in debt to

him, that he might oblige them to bring their articles to him, and that

thus he might be enabled to have them at his own price, while at the

same time he charged the highest price for his goods.

The system was a

ruinous one for all parties. The farmer was led into extravagance,

purchasing articles with which he might have easily dispensed, and which

he would not have purchased, but that the time of payment faded so far

into the distant perspective, as scarcely to be perceptible. He made no

effort to clear off pecuniary liabilities, and sat easy under a load of

accumulated debt. Many thus became involved in such a way, that they

were scarcely out of debt till the end of their days, many had to

mortgage their farms, which in many instances were never redeemed. On

the other hand, the merchant had a large amount due him according to his

books, and fancied himself making money. But when he came to settle up

his business, the pleasing delusion was dissipated. The sums due could

not be had when wanted, and after distressing the people by legal

proceedings, many of them were never paid at all, and the merchant was

sometimes ruined, while his books presented an array of figures, which

showed him to be a rich man.

Besides, the system

induced a lax sense of obligation regarding pecuniary engagements, which

to some extent has continued to the present day. The merchant would not

pay the country people cash for their produce, hut would insist on their

taking their payment in goods, and those at the highest price. The

farmer felt this an injustice to him, as the goods were not equivalent

to their rated money value, he learned to regard the interests of the

merchant as opposed to his own, and came to feel himself justified in

evading obligations—in palming off inferior articles, or in taking

advantage as he could. This became so habitual with many, that it

extended to all their dealings— with the minister as well as others; but

the latter was under the most unfavourable circumstances, as he could

not higgle or dispute about the justice of charges made, or the quality

of articles presented. Altogether we have no hesitation in saying, that

next to the free introduction of rum, nothing has been so injurious to

the social and moral interests of the Province as the credit system so

long prevalent.

In this account of the

payment of stipend and of the mode of dealing in the country, we have

rather described the state of things some years later. We therefore

return to the time at which his narrative was interrupted, to remark,

that here as before, “his deep poverty abounded to the riches of his

liberality.” Prom the very first he was distinguished by his charity.

During the early part of his ministry there came a spring, which proved

very hard upon the poor settlers. Soon after he had received a payment

on account of stipend, Donald MacKay, with whom he lodged, entering his

room on a Saturday, found him with several small piles of money before

him. “Ah,” said Donald, in his free and off-hand manner, “is that what

you are at, counting your money when you should be studying your

sermons?” “Oh,” said he in reply, “this is for such a person, and this

is for such another, to enable them to buy seed.” “But,” said Donald,

“they will never pay you back.” “Well, if they don’t, lean want it.”

Those who were acquainted with the circumstances used to say, that not

one half of it would ever have been repaid.

But the most

distinguished act of charity perhaps of-his whole life took place in the

first year of his ministry, and is referred to in the paragraph quoted

above. He there remarks regarding the money part of his first year’s

stipend, “Almost all the twenty-seven pounds were due by me to some

necessary engagements of charity which I was under.” The act of charity

here referred to we venture to say has rarely been equalled, and as he

so slightly refers to it, we must describe it more in detail. Strange as

it may appear at this date, the settlers who had come from the Old

Colonies to several parts of Nova Scotia had brought with them slaves,

and retained them as such for a number of years.2

Among others, the late Matthew Harris was the owner of a coloured girl,

who afterwards went by the name of Die Mingo, and a mulatto man, named

Martin. The question of the slave trade had just previously to the

Doctor’s leaving Scotland begun to agitate the public mind of Britain.

He had entered heart and soul into the discussion, and now when an

opportunity was afforded, he gave practical proof of his benevolence and

love of freedom. He immediately interested himself to secure the liberty

of these unfortunate individuals, and for this purpose actually agreed

to pay £50 for the freedom of Die. Of the £27 received in money the

first year, £20 was paid toward this object, and for a year or two, a

large portion of his produce payments went to pay the balance.

The poor creature was

extremely grateful, and continued till her death to have the warmest

feelings of veneration and affection for him, which feelings were

retained by her family after her. She was afterward married to George

Mingo, also a coloured person, who had served during the first American

war. They were both in full communion with the congregation of Pictou,

till their death, and esteemed as very pious persons, such as might have

served as models for Uncle Tom and Aunt Chloe. They, as was customary at

that time, used to travel round to the various sacraments, and I have

been informed by persons now old, that when children, though black

people were then generally despised, yet George and Die every where

commanded respect. She died some years ago, and the late Rev. John

MacKinlay, her pastor, used to state that he had attended the deathbeds

of but few persons, from whom he had received more satisfaction.

By the Doctor’s

influence, Mr. Harris was also persuaded to give Martin his freedom

after a certain term of good service. He afterward married a woman

belonging to River John, of Swiss descent, and removed to St. Mary’s

where he had a family. He bore an excellent character, and seemed also

to have profited spiritually by the Doctor’s instructions. On one of his

missionary excursions, the latter was afterwards at his house, and

baptized his family. He subsequently removed to the United States.

The Doctor also

relieved a woman who was in bondage for a term of years, paying some

nine or ten pounds for her freedom. He also paid for the board and

education of her daughter; but she proved a worthless character.

Yet with that freedom

from ostentation which characterized him in all his good deeds, he never

mentioned the circumstances to any of his friends at home, except barely

alluding to it in a letter to his father. One of his relatives, writing

to him, says, “Your father is at a loss, you did not signify in your

last to him your end for giving away £20 for some people in hardship,

nor what they were to you. He wishes to know.” But his good friend, Mr.

Buist, having obtained intelligence of what he had done, took measures

to give it publicity, as will appear by the following extract of a

letter from him dated March 18th 1791.

“I am much obliged for

the six copies,3 but you were not so good as to

tell me you had freed some slaves, but Mr. Fraser told me you had done

so as to two. I got Mr. Elmsley to tea, he did not know of this, but

spoke of an old woman very useful among the sick. I thought such

goodness should not be concealed, and sent to the Glasgow Advertiser,

and had inserted the following, ‘The Bev. Mr. James MacGregor, Gaelic

Missionary from the Antiburgher Presbytery of Glasgow to Pictou, Nova

Scotia, has published in that country against the slave trade, and has

since recommended his doctrine by a noble and disinterested

philanthropy, in his devoting a part of his small stipend for purchasing

the liberty of some slaves. Such is the modesty of that gentleman, that

he has not given his friends in this country the pleasure of this news,

so honourable to his society and to the Highland emigrants from

Scotland) but authentic information is received that he has purchased

and liberated two young persons, adding to the favour education at

school, and that he is in treaty for the liberty of an old woman, who

may be very useful as a nurse to the sick.’ I hope I have not offended,

nor will I beg pardon unless I have sent a false account or

misapprehension. It was copied in the newspapers through Britain, and

your name is famous. Luckily it appeared in that Glasgow paper that the

resolutions and subscriptions by David Dale for £10 and other Glasgow

gentlemen to the amount of £170, for carrying the Bill for abolishing

the slave trade appeared, and was just placed a few lines before their

advertisement requesting others to subscribe. I have virtually approved

your book.”

The letter from which

the above is taken has the following in short hand on the back, “

Received this on the 31st of May, read the account of the advertisement

with trembling and (sweat?)”

It may be mentioned

that the question of slavery was afterward settled in Nova Scotia in the

following way. Difficulties arose in an action of trover brought for the

recovery of a runaway slave, which induced the opinion that the courts

of law would not recognize a state of slavery as having a lawful

existence in the country, and although this question never received a

judicial decision, and although particular clauses of some of the early

acts of the Province corroborate the idea that slaves might be held, yet

the slaves were all emancipated.

As we have referred to

the subject of slavery, we shall here give an account of his controversy

on the subject, though it did not take place till the following year.

(1788). At the time of his intercourse with the Truro brethren on the

subject of union already referred to, he learned that the Rev. Mr. Cook

had been the owner of two female slaves, a mother and daughter. We have

been informed that he obtained the mother as a gift from a person in

Cornwallis, when on a visit there. At all events be afterwards sold her

in consequence of her unruly conduct. The daughter he seems to have

obtained by purchase. There is no evidence that Mr. Coek treated either

of them otherwise than with Christian kindness. Indeed such was his

gentleness of disposition, that it could not be otherwise. But to the

Doctor, fired with the controversy then agitating Britain on the slave

trade, the very idea of a minister of Christ retaining one of his fellow

beings in bondage was revolting, and he made this a special ground of

refusing all communion with a Presbytery, whieh tolerated such conduct

in one of its members. He also addressed to Mr. Cock a long and severe

letter on the subject. Though called a letter it was more like a

pamphlet. This was received with a sort of bewildering surprise.

Immediately after perusing it, Mr. Cock took it over to a friend, one of

the Archibalds, who had also a slave. What was the result of their joint

deliberations we know not. But in a short time they were still more

astonished by the appearance in print of a similar letter entitled,

“Letter to a clergyman, urging him to set free a black girl he held in

slavery.” This publication excited great attention. The members of the

Truro Presbytery were very indignant, as well as many of their friends,

but many throughout Colchester not only read it with deep interest, but

cordially approved of its contents.

We have published this

letter among his remains as we are certain that it will be read with

interest, not only for its subject matter, but also for its style and as

a curiosity of the times. The spirit of this production will doubtless

be regarded as deficient in Christian charity oven by many -who approve

of its principles. Indeed it presents a remarkable contrast to that

gentleness of spirit which characterized his later years, and must be

taken as exhibiting the fervour of youthful feeling. In his subsequent

letters he explains, that his strong language was meant to apply to the

acts of buying and selling our fellow men, and not to Mr. Cock

personally, and that in what lie had said he did not refer to his

motives. Whatever may be said of the spirit of this production, wc

venture to say as to its matter, that it contains, in a clear and

forcible style, a thorough discussion of the principles at issue. Though

other writers may have supplied many additional facts regarding the

nature and workings of slavery, there is very little to be added upon

the Scriptural question. It may indeed, be objected, that he confounds

slave trading and slave holding, but both involve the same principles.

Mr. Cock was a man of

very mild temper, and sat quietly under the castigation he received, but

the Rev. David Smith, of Londonderry, being of a more pugnacious turn of

mind, took up the cudgels, and several communications passed between

them. The most of this correspondence has perished, but we have in our

possession two long communications of Mr. Smith’s containing a full

exhibition of his views. We may give a summary of his arguments. Indeed

they are just such as are commonly urged by the friends of slavery in

every age. The following are the principal—that the relation of master

and bond servant implied no such power on the part of the master over

his slaves, as over his cattle, but that they were merely in the

situation of indentured servants, and that all that those who purchased

them did, was to secure a title to their services in lawful commands for

life, coupled with an obligation to instruct them in the doctrines and

duties of religion— that the slaves had been originally sold by public

authority in the states from which they came, having duly forfeited

their liberty—that Abraham had servants born in his house and bought

with his money—that there were slaves in the early

Christian Church, as

appears from Paul’s directions to masters and servants in the Epistles

to the Ephesians and Colossians, from Paul’s directions to Timothy, 1

Epis. vi. 1, 2, and also from 1 Cor. vii. 20, 21—that Paul sent hack

Onesimus a runaway slave to Philemon his master—that the relation is of

the same kind as parent and child, master and servant, ruler and

subject, and that cruelties inflicted in particular instances, did not

argue against the relation in one case more than in the other—and that

the immediate emancipation of slaves would be for their injury rather

than their good.

In reference to this

particular case, he argues that Mr. Cock, so far from being guilty of

any ill usage of his slave, treated her in the most Christian manner. We

give his statement:

“I can assure you that

Mr. Cock’s girl never was nor is still wanted by him as a slave in the

sense you understand it, but merely as a bond or indentured servant, and

from the very first time he got her and her mother, he from time to time

told me and many others, that he had no intention of always detaining

them, if they behaved themselves well. And to my own knowledge, they

were, and his girl still is, more tenderly dealt with, than the most of

hired servants in these parts.

“Notwithstanding your

confident assertions, I see no inconsistency in vour Rev. Brother’s

(Air. C.) having ground to say, ‘He hath not shunned to declare all the

counsel of God,’ and as a Christian discharged his duty to his fellow

creatures as faithfully as he could, and at the same time retaining his

bond servant; for I charitably hope iliat he is far from attempting to

lord it over her conscience, but endeavours to instruct her in the same

manner as he doth his own children, having given and daily giving her

the same opportunities with the rest of his family both as to the more

private and public means of instruction. And if all that keep bond

servants had been or were disposed to treat them in the same manner that

he hath done his—they would have reason to esteem it a happy privilege,

that ever they came under the direction and protection of such masters.

What baleful influence his example hath had or may have upon others I

cannot see.

“What were his motives

or reasons for disposing of the girl’s mother, he best knoweth, but as

far as I can learn she turned so unruly, sullen, and stubborn, as to

threaten to put hands on her own life, in which case she certainly

forfeited her liberty, and so he disposed of her to another, who had

been more accustomed to the management of such; and though she attained

to enjoy a licentious liberty, as the event verified, yet she again made

a desperate attempt both on her own life and the life of the fruit of

her womb, which laid her new master under the necessity of confining her

more than ever.”

Mr. Smith also shows

considerable adroitness, though not always fairness, in catching at

particular statements and expressions in the Doctor’s letter, as for

example, when the latter solemnly charged Mr. Cock to liberate his

slave, because till he did so, none of his services could be acceptable

to God, he (Mr. S.) represents this as teaching the doctrine of securing

acceptance with God by our own good works. The following specimen of his

argumentation is of a similar character. “Did not your own conduct in

purchasing a negro girl make you as deeply guilty as the Rev. Mr. Cock?

It is in vain to plead, you purchased her freedom, for if it was such a

heinous sin in Mr. Harris to keep her; is it not as heinous a crime in

you to pay for her freedom? According to your principles her price is

the wages of iniquity, and surely the giver is as deeply guilty as the

receiver.”

He also complains much

of the bitter spirit of the Doctor’s letter, and accuses him of

“exciting a spirit of faction and party, respecting such things as

neither directly respect the faith and practice of the church.” He also

indulges in personal recrimination, which we need not farther notice.

We have given the facts

on this subject, so far as we have been able to gather them, as from the

prominence which the affair had in his life at that time, it could not

be omitted, and because we regard it as a curious episode in the history

of the Province. "We have done so with no feelings against the other

party concerned. Mr. Cock was undoubtedly a good man, and acted on his

light, and when we consider the large number of excellent men, who even

in the present day defend slavery, we need not wonder, that a minister

at that time should have followed a practice, the wrongfulness of which

had only begun to be exposed. The girl who from that date was commonly

called Deal MacGregor, in consequence of the Doctor’s speaking of her in

his letter as his sister, continued with Mr. Cock as long as he lived.

It is commonly said by those who knew the facts of the case, that it had

been well for his family, if she had never been admitted into it.

The subjects we have

now been discussing have carried us ahead of his narrative. We therefore

return to it.

"As soon as the

meeting-houses were built, the people set themselves to make roads to

them, that they might be as accessible as possible by land. But these

roads were nothing more than very narrow openings through the woods, by

cutting down the bushes and trees that lay in their line of direction,

and laying logs, with the upper side hewed, along swampy places and over

brooks, which could not be passed dry, by way of bridge. The stumps and

roots, the heights and hollows, were left as they had been. The chief

advantage of this was, that it prevented people from going astray in the

woods. During winter, the roads and meeting-houses both were totally

useless; for the preaching was in dwelling-houses, with fire.

“I followed the same

plan this winter that I did the winter before; I took the opportunity of

visiting and examining, and did so with much the same success, for with

many an evident progress was discernible. As I went round from river to

river, I saw much diligence in attending public ordinances; many taking

pleasure in religious conversation, and numbers under great anxiety

about the state of their souls; but numbers were also careless and

ignorant, and not a few were irritated.

“When summer arrived, I

had to set my face to the dispensation of the sacrament of the Supper,

without an assistant. The best members of my congregation were willing

to have the assistance of one or both of the Colchester ministers, but I

could not get over my scruples to invite them, and happy was it for me

that they (the congregation) were so temperate. It was no small grief to

me that I could not accept of the assistance of my brethren, but, except

to a few individuals who were previously irritated, it caused no offence

in the congregation. They were more sorry for my own fatigue than for

any thing else.

“The session appointed

the sacrament to be dispensed on the 27th of July, a little above the

head of the tide on the Middle River, the most central place that could

be found. It was ;i beautiful green on the left bank of the river,

sheltered by :\ lofty wood and winding bank. There, in the open air, the

holy Supper was administered annually, as long as I was alone. Though it

is thirty years since its last administration there, I never see the

place without an awful and delightful recollection of the religious

exercises of my youth, and of my young congregation, when, if I mistake

not, we had happier communion with God than now, when our worldly

enjoyments are ten times greater. Jer. ii. 2, ‘Go and cry in the ears of

Jerusalem, saying, Thus saith the Lord, I remember thee, the kindness of

thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in

the wilderness, in a land that was not sown.’

“The day for dispensing

the sacrament was published five weeks beforehand, that there might be

sufficient time for examining intending communicants; and they were all

particularly examined. It was agreed that the preceding Thursday should

be observed as a day of public humiliation and prayer for preparation ;

and that the English should be first this year, and the Gaelic the next

year, and so on alternately. On the humiliation-day I earnestly exhorted

the congregation to examine themselves impartially and thoroughly, to

renounce hypocrisy and self-righteousness, to lay hold on the hope set

before them in the gospel, and implore the gracious and merciful

presence of God on the ensuing occasion, as I was a young and

inexperienced minister, and the most of them were to be young and

inexperienced communicants; and the first dispensation of the sacrament

might have lasting effects of good or evil. I preached first in English,

then in Gaelic, on the Thursday, the Saturday, and the Monday. On

Sabbath I preached the action-sermon, fenced the tables, consecrated the

elements, and served the first two tables in English, at which all the

English communicants sat. The singing in English continued till all the

Highlanders, who were waiting, filled the table. I then served two

tables, gave directions, and preached the evening sermon in Gaelic. The

work of the day was pretty equally divided between the two languages.

But the Highlanders wanted the action-sermon, and the Lowlanders the

evening sermon. This, however, could not be helped, but the want was

partly supplied by previous instructions and directions.

“This was the first

sacred Supper dispensed in Pictou; and though some, no doubt,

communicated unworthily, yet I trust that a great majority were worthy.

There have been some instances of apostasy, but they are few.

Four-fifths of them have given in their account to the great Judge, and

I hope few of them made shipwreck of faith; many of them adorned their

profession, living and dying. The number of communicants was one hundred

and thirty, of whom one hundred and two were heads of families, ten

widowers and widows, living with their children, eight unmarried men,

and ten strangers from Merigomish.'”

We shall speak more

particularly hereafter of the dispensation of the Supper in the early

years of his ministry. It may be interesting to add here such an account

as we can give of the discourses preached on the occasion. For several

Sabbaths previous he preached with reference to the observance of the

Institution. The following are some of the subjects : on June 14th, 1

Cor. x. 16, “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion

of the blood of Christ?” 1 Cor. x. 17—26: on June 28th, 1 Cor. v. 6, 7,

8. Two discourses; July 5th, 1 Cor. xi. 28, “But let a man examine

himself and so let him eat of this bread and drink of this cup and Psal.

xv.; on July 12, 1 Cor. 11-28,—Psal. xxvi. 1-7. On the Saturday previous

to the dispensation of the ordinance he preached on Josh. iii. 5,

“Sanctify yourselves; for to-morrow the Lord will do wonders among you;”

and on Psal. x. 17, “ He will prepare your heart.” His action sermon was

on Song ii. 16, “ My beloved is mine and I am his;” and on the evening

of Sabbath his text was Psal. cxvi. 12, “What shall I render unto the

Lord for all his benefits toward me ?” We find a sermon on Luke vi. 40,

“ The disciple is not above his master, but every one that is perfect

shall be as his master,” marked, “ intended for Monday j” while on the

Sabbath succeeding he preached on Psal. cxvi. 18, “ I will pay my vows

unto the Lord, now in the presence of all his people,” and lectured on

verses 12—19 of the same Psalm. It will be seen that he occupied mueh

time and labour in preparatory discourses. More of this was necessary,

than would have otherwise been, in consequence of the preaching being in

different places, and it being requisite on each day to have one sermon

in English and one in Gaelic. We shall give an outline of one of his

Saturday sermons, and of his action-sermon :—

“Josh. iii. 5.—Sanctify

yourselves, for to-morrow the Lord will do wonders among you.”

“I. Of the wonders

which God will do.

1. He will let you see

the evil of sin. Christ the beloved Son of God was brought by it to

death. This was done by your thoughts, words, and actions. If yon can

understand the whole sufferings of Christ, you may understand all the

evil and all the desert of sin.

2. He will show the

severity of God’s justice. He would not be satisfied with thirty-three

years’ obedience. He required all the sufferings of his soul till his

body was broken. “ Awake, O Sword, &c.” God loved him and was gracious

to him, but that would not do. What will become of self-flattering

sinners?

3. The love of God: of

the Father in giving his Son whom he infinitely loved to be broken for

us, and the Son in suffering for us, and the Holy Ghost in coming into

sueh hellish hearts to prepare us for eating the broken body of Christ.

4. The virtue of

Christ’s blood, to take away the guilt of sin, to give peaee to the

conscience, in spite of sin and hell, to purify the heart, to strengthen

it for God’s service, to fill it with the joy and peace of believing, to

prevent our fears and exceed our hopes, to feed our souls.

II. Of our

sanctification.

1. This says that we

should understand something of God’s holiness. He is so holy that lie

cannot keep communion with sinners—that the angels cover their faces,

and that no unclean thing is meet to come before him.

2. That we are sensible

of our unholiness, our original and actual transgressions, and that by

these we are altogether as an unclean thing, a lump of hell.

3. That we are to

depend on the Spirit for sanctification. We cannot sanctify ourselves.

The Spirit is promised to sanctify us, and there is influence in

Christ’s blood to sanctify us, and we must apply to this in the diligent

use of means.

4. We are to retire

from the world, and to examine our hearts, that we may part with

whatever displeases a holy God, and that we may get a suitable frame of

spirit to attend upon him. We are to cast out pride, the world,

unbelief, malice, and vain thoughts. We arc to be in a humble,

spiritual, fixed, loving, lively frame.

III. Of the reasons of

it.

1. Because of the

deceit of our hearts, which would outwit us if wc are not diligent, ‘

The heart is deceitful above all things.’

2. God’s jealousy for

his holiness. He would break forth upon us. Ex. xix. Iii, 21, 24.

3. Because God delights

himself in them that arc sanctified. Psa. lxxxvi. 2. ‘Holiness becomes

God’s house.”’

Outline of action

sermon on Song ii. 16. “ My beloved is mine and I am his.”

“I. My beloved is mine.

1. His righteousness is

mine to pardon my sins, and make me be accounted as righteous in God’s

sight, Jer. xxiii. 6; 2 Cor. v. 21. From blackness of hell he will make

me fair as heaven. Isa. lxi. 10.

2. All his gracious

promises are mine to quicken, sanctify, and save me. Faith puts all the

promises of grace in my possession, and then all the grace in the

promise is my property. Quickening grace, John v. 25, reviving grace,

Hos. xiv. 7, sanctifying grace, Ezek. xxxvi. 25, 26, saving grace, Isa.

xlv. 17, grace to overcome sin, Satan, and the world, 2 Cor. ix. 8;

Phil. iv. 19.

3. His Father is mine,

John xx. 17, to pity me, Fsa. ciii. 13, 14, to protect me, Jer. iii. 4,

to accomplish all the promises of the covenant of grace, Psa. lxxxix. 4;

John xvi. 27, to be my portion for ever, Psa. lxxiii.

4. His Spirit is mine,

Rom. viii. 9, to teaeh me to pray, Rom. viii. 26, 27, to give me

knowledge, Eph. i. 17, to sanctify me, 2 Thess. ii. 13, to apply a

complete redemption to me, John xvi. 14.

5. My beloved’s person

is mine, and all that he hath is mine. He is mine as God, and mine as

Mediator; his divine perfections are mine, as power, wisdom, and

holiness. The obedience and sufferings of the human nature are mine, to

free me from the wrath to eome. As Mediator he is mine, to be my example

to which I must strive to be more and more conformed, and to be mine

eternal portion.

II. And I am his.

1. All my sins are his,

Isa. liii. 6, my original sin and all my actual sins are his by

imputation, 1 Pet. ii. 24, and so the punishment of them is his, Isa.

liii. 4, 5 ; 1 Pet. iii. 18. My unworthy communicating is his.

2. All my sins, and

infirmities, and failings, and afflictions, in a state of grace, are

his. When I was nothing to him he took me and all my faults, Hos. ii.

19, 20 ; Psa. xcix. 8.

3. All my graces are

his, for they are from him and shall be to him. 1 Cor. xv. 10. * By the

grace of God I am what I am.’ I\ly fuith glorifies the truth and

faithfulness of his promise, my love is the reflection of his, all my

humility is the reflection of his condescension, and my patience the

effort of his strength, 2 Cor. xii. 9.

4. My person, and my

ability, and my talents, and all that I have and can do are his for

ever, 1 Cor. vi. 19, 20; Matt. x. 37, 38; Isa. vi. 8: Psa. cxvi. 16.

Hence sec:

1. That persons need to

look what they are doing, when they take and profess our religion. They

then give themselves away, Matt, x. 39.

2. What is the proper

work for a communion Sabbath, to be saying, ‘ My beloved is mine and I

am his.’ God is for him in his soul. Give you yourselves to him in your

soul.

3. What will make us

worthy communicants. Christ is the fountain of grace. Go to him for all

that you need.

4. How foolish they are

who despise Christ. ‘ All that hate me love death.’ They lose the best

jewels that exist for nothing.” |