|

Not long ago I had the

honour of reading before the Institute of Science a paper describing a

number of aboriginal relics found in this province. It was based on a

study of the many excellent specimens preserved in the cases of the

Provincial Museum, Halifax. Since that time, a quantity of undescribed

and very interesting material has been placed in my hands, which I shall

herein describe.

A number of years ago the late Charles W. Fairbanks, Esq., C. E., formed

a collection of stone implements which had been discovered in Nova

Scotia. Most of these relics were given to him by William M. King who

found them while clearing and plowing the land on his farm at the head

of Grand Lake, Halifax County. The place was doubtless a prehistoric

camping ground, but I do not know whether the Micmacs continued to

resort there within the memory of man.

Mr. Fairbanks’s collection is now the property of his son, Charles R.

Fairbanks, Esq., of Halifax, to whom I am indebted for permission to

examine and describe the specimens. Very unfortunately none of them bear

labels, and therefore the exact localities where they were found are

unknown; but there is no doubt that they are Nova Scotian, and probably

nearly all were found on Mr. King’s farm.

I have also to thank several other gentlemen whose names are

subsequently mentioned, for permission to study implements in their

possession.

These specimens, together with some in the McCulloch collection of

Dalhousie College Museum, and others of my own, constitute tire material

upon which the present paper is founded.

Before entering upon a description of these implements, it may be well

to consider the habits of our Indians as described in the writings of

one of the early voyagers. This will help us much to understand the

subject with which we deal. The first exact and extensive account of the

Micmacs, and by far the most interesting, is to bo obtained from the

description of New Franee written by the old French advocate, Mark

Lescarbot, who accompanied Poutrmeourt to Acadie. He dwelt for some time

at Port Royal, now known as Annapolis, which had been founded in the

previous year by Pierre du Guast, Comte de Monts From an English version

of Lescarbot’s rare book, in the library of the late Dr. Akins, I have

made some transcripts which follow in the quaint language and spelling

of the translator. These extracts will be of great interest to any who

are studying the archieology of Nova Scotia, for Lescarbot wrote at the

period when iron implements were only beginning to supplant those of

stone. Dr. J. B. Gilpin has already given us much information gathered

from this writer, but seldom in the hitter’s language.

Speaking of the dress of the Indians, Lesearbot says they wore “ a skin

tied to a latch or girdle of leather, which passing between their

buttocks joineth the other end of the said lateh behind . and for tho

rest of their garments, they have a cloak on their backs made of man}7

skins, whether they be of otters or of beavers, and one only skin,

whether it be of ellan, or stag’s skin, bear, or lucerne, which cloak is

tied upward with a leather ribband, and they thrust commonly one arm

out; but being in their cabins they put it off, unless it be e<Al....As

for the women, they differ only in one thing, that is, they have a

girdle over the skin they have on and do resemble (without comparison)

the pictures that be made of St. John Baptist. But in winter, they make

good beaver sleeves, tied behind, which keep them very warm.... Our

savages in the winter, going to sea, ora hunting, do use, great and high

stockings, like to our boot-hosen ; which they tie to their girdles, and

at the sides outward, there is a great number of points without taggs

...Besides these long stockings, our savages do use shoes, which they

call mekezin, which they fashion very properly, but they cannot dure

long, especially when they go into watry places, because they be not

curried nor hardened, but only made after the manner of butt, which is

the hide of an ellan. As for the head attire, none of the savages have

any, unless it be that some of the hither lands truck their skins with

Frenchmen for hats and caps; but rather both men and women wear their

hairs flittering over their shoulders, neither bound nor tied, except

that the men do truss them upon the crown of the head, some four fingers

length, with a leather lace, which they let hang down behind.

Describing the complexion of the savages, Lescarbot says: “They are all

of an olive colour, or rather tawny colour, like to the Spaniards, not

that they be so born, but being the most part of the time naked, they

grease their bodies, and do anoint them sometimes with oil, for to

defend them from the files, which are very troublesome All they which I

have seen have black hairs, some excepted which have Abraham colour

hairs; but of fiaxen colour I have seen none, and less of red.”

The Indians have

matcichias, hanging at their ears, and about their necks, bodies, arms,

and legs. The Brasilians, Floridians, and Armouchiquois, do make

carkenets and bracelets (called boare in Brasil, and by ours matachims)

of the shells of those great sea cockles, which be called vignols, like

unto snails, which they break ami gather up in a thousand pieces, then

do smooth them upon a hot stone, until they do make them very small, and

having pierced them, they make them beads with them, like unto that

which we call porcelain. Among those beads they intermingle between

spaces other beads, us black as those which I have spoken of to be

white, made with jet, or certain hard and black wood which is like unto

it, which they smooth and make small as they list, and this hath a very

good grace. They esteem them more than pearls, gold or silver.... But in

Port Royal. and in the confines thereof, and towards Newfoundland, and

at Tadoussac, where they have neither pearls nor vignols, tho maids and

women do make matachias, with the quills or bristles of the porcupine,

which they doc with black, white, and red colours, as lively as possibly

may be, for our scarlets have no better lustre than their red dye; but

they more esteem the mutmhias which come unto them from the

Armouchiquois country, and they buy them very dear; and that because

they can get no great qunnity of them, by reason of the wars that those

nations have continually one against another. There are brought unto

them from Franco matachiOfi made with small quills of glass mingled with

tin or lead, which arc trucked with them, and measured by the fathom,

for want of an ell.”

“Our savages have no base exercise, all their sport being either the

wars or hunting ... or in making implements fit for the same, as Ciesar

witnesseth of the ancient Germans, or in dancing . . . or in passing the

time in play.” Lescarbot then describes their bows and arrows, but as I

have elsewhere referred to this account, it may be here omitted. “They

also,” he says, “ made wooden inases, or clubs, in the fashion of an

abbot’s staff, for the war, and shields which cover all their bodies As

for the quivers that is the women’s trade.

For fishing: the Armouchiquois which have hemp do make fishing lines

with it, but ours that have not any manuring of tho ground, do truck for

them with Frenchmen, as also for fishing-hooks to bait for fish; only

they make with guts bow-strings, and rackets, which they tieat their

feet to go upon the snow a hunting.

“And for as much as the necessity of life doth constrain them to change

place often, whether it be for fishing (for every place hath its

particular fish, which come thither in certain season) they have need of

horses in their remove for to carry their stuff. Those horses lie canoes

and small boats made of harks of trees, which go as swiftly as may he

without sails : when they remove they put all that they have into them,

wives, children, dogs, kettles, hatches, matochias, bows, arrows,

quivers, skins, and the coverings of their houses. . . . They also make

some of willows very properly, which they cover with the . . gum of

fir-trees; a thing which witnesseth that they lack no wit, where

necessity pressoth them.”

Lescarbot says that anciently the Souriquois or Miemacs made earthen

pots and also did till the ground; “but since that Frenchmen do bring

unto them kettles, beans, pease, bisket and other food, they are become

slothful, and make no more account of those exercises.”

Elsewhere in the volume the writer also tells us that the labour of

grinding corn to make bread “is so great, that the savages (although

they he very poor) cannot hear it; and had rather to be without bread,

than to take so much pains, us it hath been tried, offering them half of

the grinding they should do, hut they chused rather to have no corn.”

Writing of the women, he says, that “when the harks of trees must he

taken off in the spring-time, or in summer, therewith to cover their

houses, it is they which do that work: as likewise they labour in the

making of canoes and small boats, when they arc to he made: and as for

the tilling of the ground (in the countries where they use it) they take

therein more pains than the men, who do play the gentlemen, and have no

care but in hunting, or of wars. And notwithstanding all their labours,

yet commonly they love their husbands more than the women of these our

parts.”

Once Lescarbot saw meat cooked by an Indian in the following manner. The

savage “did frame with his hatchet, a tubb or trough of the body of a

tree,” in which he boiled the flesh by "putting stones made red hot in

the fire in the said trough,” and replacing them by others until the

meat was cooked.

Speaking of some Indians who followed the French vessel along the sands,

"with their hows in hand, and their plovers upon their hacks, always

singing and dancing, not taking euro with what they should live by the

way,” the worthy advocate exclaims with enthusiasm, “Happy people! yea,

a thousand times more happy than they which in these parts made

themselves to be worshipped; if they had the knowledge of God and of

their salvation.”

We shall now leave the old French narrator and proceed to discuss the

examples of aboriginal skill with which this paper is chiefly concerned.

In classifying the specimens, I have principally adopted the arrangement

given by Dr. Charles Han in his account of the archaeological collection

of the United States National Museum (Washington, 187(5.) In a few

cases, however, I have found it necessary to depart slightly from his

nomenclature.

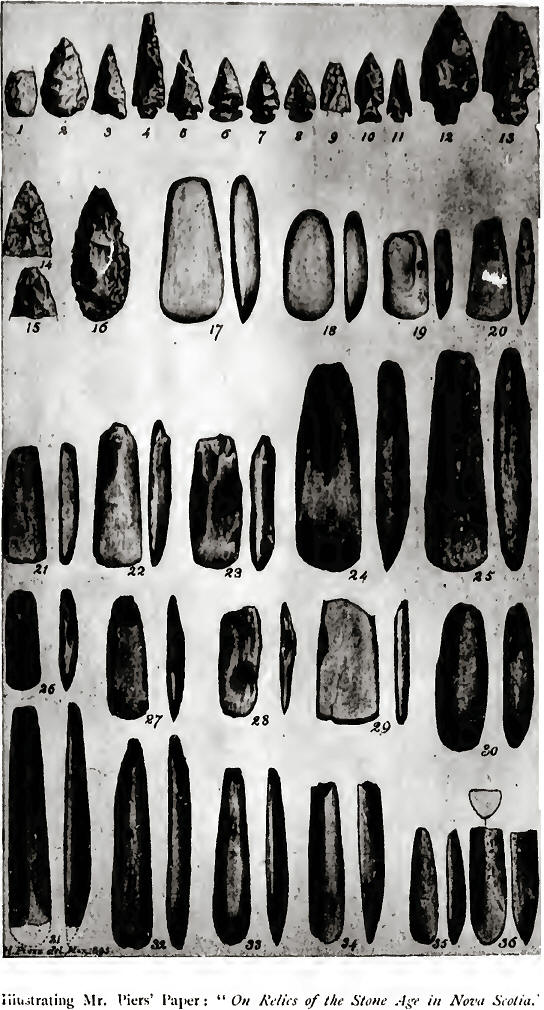

A.—FLAKED AND CHIPPED STONE.

Arrow-hetids.—The collection before me contains eleven specimens which I

have so denominated. This is rather a small number, but it is very

likely that several have been lost or given away since the formation of

the collection. Some of the implements are flaked with great skill. With

one exception, to be hereafter noted, all are formed of silicious

stones, mostly jaspideous, such as are found in the western parts of the

province. None have been polished in any degree. All are the result of

the ordinary process of flaking by pressure. The points are mostly

unfractured. In length the specimens vary from 125 in. (Fig. 8) to

nearly 2’75 ins. (Fig. 4). Larger implements of this kind are

denominated “ spear-heads.” The distinction, however, is an arbitrary

one; for without the handle, which almost invariably has utterly

decayed, there is no means by which an archaeologist, in the present

state of our knowledge, can form a fixed rule by which he may assert

positively whether a given head was used as a spear, an arrow, or a

knife. It is very likely that some of the larger so-called arrow-heads,

as well as many of the “spear-heads,” were hafted and employed as

cutting tools. Owing to this uncertainty as to the method of use, Dr.

Wilson of the U. S. National Museum, in his Study of Pro-historic

Archaeology (1800), treats of all those implements under the general

head of “arrows or spear-heads, or knives.”

The specimens (Figs. 1—2) are leaf-shaped with rounded (convex) bases.

The proportions and finish of one of these (Fig. 2) makes it possible

that it may have been a leaf-shaped implement either intended to lie

hufted as a knife, or else inserted in the head of a club. In uppeurunce

it resembles some of the pabrolithic implements of Europe, and it

probably belongs to that hitherto much neglected class of aboriginal

remains which. Dr. Wilson considers to be indicative of a palaeolithic

period in American archaeology. Professor Wilson’s researches in this

direction are most interesting and important, and open a new and wide

field for investigation.

Another specimen is straight-sided with a slightly concave base (Fig.

8). Five well-formed specimens (Figs. 4-8) are notched at the sides near

the base. This class includes both the largest and the smallest example

(2’75—1’2 ins.). The former (Fig. 4) would have been grouped with the

spear-heads but for its slight proportions. A sixth specimen (Fig. 0) is

broken, but possibly belongs to this class. Only one (Fig. 10) is

stemmed and has a slightly concave base. The stem, like the notched

sides before mentioned, was to facilitate the attachment of the head to

a shaft. The last specimen to be considered, is barbed and stemmed (Fig.

11). It is two inch in length, and is neatly chipped from an olive-green

or slightly smoky-coloured material, which from the smooth, curved

surface of one side, und other appearances, seems to be nothing but

bottle-glass.

An interesting account of the bows and arrows of our Indians is found in

the quaint account of the old French advocate before quoted. The bows,

saith Lescarbot, “be strong and without fineness.” “As for arrows,”

continueth he, “it is an admirable thing how they can make them so long

and so strait [sic] with a knife, yea with a stone only, where they have

no knives. They feather them with the feathers of an eagle’s tail,

because they arc firm and carry themselves well in the air: and when

they want them they will give a beaver’s skin, yea, twain for one of

those tails. For the head, the savages that have traffic with Frenchmen

do head them with iron heads which are brought to them; but the

Armouchiquois, and others more remote, have nothing but bones made like

serpents’ tongues, or with [sic] the tail of a certain fish called mcium.

As for the quivers, that is the women’s trade.” Bow-strings, according

to the same authority, were made of intestines, and snow-shoes or

rackets were strung with the same material.

Spear-heads (or Cutting Implements— Two stemmed specimens (Figs. 12-13),

one perfect, the other without the point, are in the Fairbanks

collection. The uninjured one is three inches long, and the other,

without doubt, was the same length. Two fragments (Figs. 14-15), one of

which (Fig. 14) had been a very beautiful and delicate weapon, may also

be placed in the present class. A fifth specimen (Fig. 16), 3'50 inches

long and somewhat thick, formed of an argillaceous stone, roughly fiaked,

may be a spear-head or else a leaf-shaped implement for use as a cutting

tool or for insertion in the head of a club.

The McCulloch collection, Dalhousie College, Halifax, contains a few

stone implements, among which is a stemmed and slightly barbed

spear-head (Fig. 82), 4 inches in length and k ±5 inches in greatest

breadth. The same collection also contains a leafshaped implemement

(Fig. 81) of white quartz, 475 inches long and 2 inches in greatest

breadth.

There remain to be described a couple of implements which may best be

considered here, although, strictly speaking, they are of polished

stone. The inconsistency of placing them under the general head of

flaked implements, is immaterial and may be pardoned.

Ur. Henry Sorette, of Bridgewater, N. S., has sent me a drawing of a

very remarkable implement of unusual length which was found with other

relics while excavations were being made for a canal at Milton, Queen’s

County, N. S. The implement may be likened to a poniard blade.

Apparently it had been ground into shape. It is 18 inches long and

tapers regularly from 175 inch in width at the base, to about 75 of an

inch (according to the drawing) in width at a distance of about

three-quarters of an inch from the end, where it suddenly diminishes to

a point. Mr. Sorette’s drawing seems to indicate a central line of

elevation from base to point. My informer thinks it is made of hard

slate. While being taken from the ground, it was broken into four

pieces. Doubtless this relic was a ceremonial implement, such as some of

the exquisitely flaked blades, long and delicate, which have been found

in California. Its fragile character would forbid any rough usage such

as that of war or sport. Strange to say, one or more other implements of

this type were discovered with it at Milton. Mr. John S. Hughes of the

Milton Pulp Company, in a letter to me relative to this discovery, says,

‘ quite a number of relics were found when we were excavating for the

canal; they consisted of stone chisels, gouges, and ‘ swords or

fish-spears ’ about 20 to 24 inches long [i. e., poniard-shaped stone

blades, one of which has just been described]. The articles were

generally kept by the finders. Out of the lot I got one gouge, and Mr.

Sorette has one of the swords.”

In the McCulloch collection already referred to, there is a polished

slate “spear-head” with a stem notched on the sides to facilitate the

attachment of a handle or shaft (Fig. 83). A portion of the point,

probably about three-quarters of an inch, is missing. It measures nearly

6 50 inches in length, by 135 inch in width at the base of the blade,

from which place it tapers very gradually to the broken point. The

central portion of the blade is flat. This flat part is bordered on both

sides by conspicious bevels, thus forming the edges. The specimen is

unlabelled, but all of the implements in the collection of which it

forms part are understood to have been found in Nova Scotia. Ground

stone implements of this kind are extremely rare in the province. Dr. J.

B. Gilpin in his aecount of the stone age of Nova Scotia (Transactions

N. S. I. N. S., vol. iii.) mentions an arrow-head which was polished

like a celt and made of hardened slate ; and a spear-head also of slate,

similarly fashioned, is referred to in my account of the aboriginal

remains in the Provincial Museum. These are all which have come to my

notice.

Before passing to the next class, I may repeat that I consider it

extremely unlikely that the implements now under notice were actually

used as spear-points. Arrow-shaped implements more than 275 inches in

length, have been denominated spear-heads in this paper more from the

general custom of archaeologists than my own inclinations. Lescarbot

makes no mention of spears as one of the weapons of the Micmacs or

Souriquois of his day, although he enumerates with a good deal of detail

their other implements of war, such as bows and arrows, and clubs. This

negative evidence has not been sufficiently noted. It is far more

probable that most of the so-called spear-heads and leaf-shaped

implements found in Nova Scotia, are knives. Our Micmacs had stone tools

for fashioning bows and arrow-shafts and for skinning animals, and yet

they are seldom reeognized by collectors. This indicates that the Indian

knife has been confounded with some other implement which it resembles.

“Collectors are very ready,” says Dr. Rau, to class chipped stone

articles of certain forms occurring throughout the United States as

arrow-and lance-heads.” Such has been much the habit of our local

writers. The spear-shaped implements mud be considered as being fairly

adapted for cutting. The Pailltes of Southern Utah, up to the present

time employ as knives, blades

made of chipped stone and identical in form with what are too frequently

termed spear or arrow-heads. These are inserted into short wooden

handles. According to Major J. W. Powell, these knives are very

effective, especially in cutting leather. The natives of Alaska still

occasionally use knives formed in a similar manner, which they carry in

a rough wooden scabbard. A most .significant fact is mentioned by the

late Dr. Gilpin. An admirable Indian hunter named Joe Glode, once shot a

moose in Annapolis County. Not having a knife, he immediately took the

flint from his gun, and without more ado, bled and dressed the carcass

therewith. Lescarbot, in a sentence before quoted, mentions the

occasional use of a stone in fashioning arrow-shafts.

13.—PECKED, GROUND, AND POLISHED STONE.

Polished Stone Hatchets or Celts, and Adzes.—These two groups I have

classed together, for although the tools I shall here describe are

usually termed celts or, more correctly, stone hatchets, in most

archaeological books, yet after a careful examination of a great many

specimens found in this province, 1 have come to the conclusion that

nearly all of those specimens, in form or otherwise, bear evidence of

having been used as adzes, mostly hafted to wooden handles in the manner

still or until recently exemplified in the stone implements of the South

Sea Islands and elsewhere. This was accomplished in the following

manner. A branch of sufficient stoutness was obtained, together with

part of the stem from which it sprang. The stem portion was then split,

forming a flat surface, and the superfluous wood having been trimmed

therefrom, the flat portion was applied to the face of the stone tool

which was then lashed to it by means of raw-hide thongs or possibly

withes. Owing to the tapering form of the stone head, every blow would

tend to tighten the hold of the binding. A piece of skin was perhaps

interposed between the handle and the stone, as the Indians of Dakota

have been known to do in fashioning their bone hoes or adzes. There

cannot be a doubt that most of the specimens, hereafter to be described,

were so hafted and used as adzes, their form making it very manifest.

Some may have been encircled a couple of times with the central portion

of a withe, the ends of which when bound together would form an

adze-handle, but one not so convenient as that just described.

Occasionally they may have been held directly in the hand, and used as

an adze, but I do not think it is at all probable.

The evident adze-like form of so-called celts or polished stone hatchets

found in Nova Scotia, has been largely or entirely overlooked by writers

upon the subject; neither Dr. Gilpin nor Dr. Patterson having paid

sufficient attention to this most interesting fact. To me it seems of

much importance. Scarcely a “celt” can be found which does not give rise

to a suspicion that it had been used as an adze. Further attention will

be drawn to this in the pages which follow. Our Indians, like some

oriental peoples, seem to have preferred a drawing cut or one made

toward the body. This is very evident and remarkable in the present

drawing-rnethod in which the Micmacs use their home-made steel knives, a

method which is entirely at variance with the practice of those about

them. This of course is the survival of a very ancient habit, and must

not be lost sight of by investigators.

In answer to an inquiry upon the subject, Dr. Bailey tells me that in

all New Brunswick celts there is a difference of curvature on the two

sides—one being flat than the other; but the amount of difference varies

a good deal, and in some cases is hardly perceptible.

Mr. David Boyle, whose name is prominent in Canadian archaeology, also

writes me that about nine-tenths of the “celts” found in Ontario are

flat, or comparatively flat, on one side, which is more or less

indicative of their having been adzes. One thousand stone axes or adzes,

at least, are in the museum of the Canadian Institute, of which Mr.

Boyle is curator.

He furthermore mentions a significant fact which shows how prevalent

among the Eskimo is the adze method of hafting. “It has been recently

observed,” he writes, “that when European hatchets have been given to

these people, they invariably take out the handle and attach another

sidewise, by binding it with thongs or sinews through and around the

eye.”

Murdoch also says that the Indians of the north-west coast of America

always re-haft as adzes any steel hatchets which they obtain by trade.

In some cases they even go to the great trouble of cutting away parts of

the implement in order to better adapt it to the new method of use.

Lieut. T. Dix Bolles in his catalogue of Eskimo articles collected along

the north and north-west coast of America, mentions no axes among the

many thousands of objects noted. There were, however, twenty adzes,

eighty-seven adze-blades, and eleven adze-heads. Dr. Wilson, of the U.

S. National Museum, says that the same condition exists all down the

coast to Lower California, no stone tools—save in one instance— having

been found which undoubtedly had been used axe-\vise. Among certain

tribes, I understand a grooved implement is found which is used as an

axe, but among the Eskimo it is replaced by the grooved adze. The line

between these two implements is now being investigated. Does the

prevalence of the adze-form in Nova Scotia indicate in any way the

influence or presence of the more northern race? There is evidence to

show that the latter people once inhabited the country much to the south

of the region in which they now dwell, and the Micmacs at one time waged

war upon them, as described by Charlevoix.

To return once more to the form and use of the so-called celts found in

Nova Scotia, it may be said that the few specimens which are not

distinctly more convex on one side than on the other, possibly were

inserted in clubs or used as hatchets. With a wooden mallet they could

be used without a haft as wedges to split wood, which might sometimes be

necessary; but they could never be struck with a stone hammer as some

suggest. The more common adze-like form, however, was well adapted for

very many uses to which it might be put by savage man, such, for

instance, as clearing away the charred wood in the process of forming

various hollow vessels by the action of tire, cleaning fresh skins of

adhering particles of flesh, and numerous other operations. Lescarbot

mentions that the Armouehiquois (Indians inhabiting what is now called

New Hampshire and Massachusetts), Virginians, and other tribes to the

south, made wooden canoes by tin. aid of fire, the b**rnt part being

scraped away “with stones.”

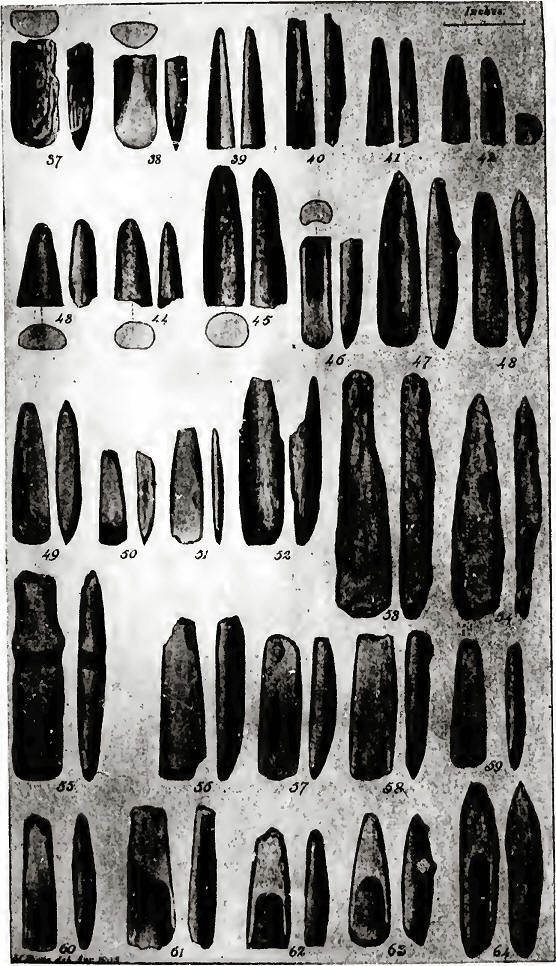

Thirty-eight of these so-called celts or adzes, either complete or

fragmentary, are in the Fairbanks collection (Figs. 17-54), and nearly

all show some indications of the adze-form to which I have drawn

attention. This will be seen by reference to the side views of the

implements shown in the accompanying plates. In size they vary from 4.50

to about 11.75 inches in length. All taper more or less toward the butt

or end farthest from the edge. The latter is nearly always much rounded,

producing a gouge-like cut, well suited to such uses as forming hollows

in wood, dressing skins, etc.

Two typical specimens may be selected in order to exemplify differences

in form. The first (Fig. 17) which illustrates the broader form,

measures nearly 7*50 inches in length and .‘125 in width near the

cutting edge, thence tapering to 210 in width close to the butt, where

it rounds off. The greatest thickness is 1.60 inch. The implement has

been intentionally formed somewhat flatter on one side than on the

other. This is quite noticeable. The flattened side is more polished

than the other, probably from the friction of a haft.

About eight or nine specimens resemble this form pretty closely, a few

others less so (Figs. 17 to 30). One (Fig. 25) is nearly 11 inches long

by 325 in greatest breadth, and weighs 57 ounces. Another specimen (4 50

X 2 25 x 75 ins.) is formed of a greenish-tinted stone, line in texture,

and capable of bearing an excellent polish and a fine edge (Fig. 19). It

differs in material from all other specimens in the collection, but

resembles in this respect, as well as in shape, a small felsite

implement from Summerside, P. E. I., which is described in my paper on

the aboriginal remains in the Provincial Museum.

To illustrate the second or move elongated form, I shall take a fine,

well-formed specimen (Fig. 31), the production of which must have cost

its maker much skilful labour. It was originally about 11-75 inches

long, but an inch of the end bearing the edge has been broken off. At

the brotder extremity, it measures 2 inches in width, from which it

lapers gradually and gracefully until it measures 1'20 in breadth at the

butt. The thickest portion—about 4 inches from the cutting edge previous

to being fractured—measures 125, from which it becomes rapidly thin in

order to form a sharp edge, and very gradually thinner toward the

opposite end or butt. Its weight is about 26 ounces. One side of the

tool is almost perfectly fiat, contrasting greatly with the rounded form

of the other side. In the present specimen and some others which

resemble it in this respect, the central line of elevation from end to

end, on the convex side, is very noticeable and adds not a little to the

beauty of the implement; others are more regularly rounded and do not

exhibit this ridge. A section at right angles to the length would be

plano-convex in outline. The specimens which most nearly resemble this

typical one. have the edge very much rounded or nearly semicircular, and

so produce a deep cut like that made by a gouge.

Some twenty specimens (Figs. 31-50)—eleven of them being parts of broken

implements—may be described as evidently of this form, and a few others

resemble it more or less. They are without the slightest doubt adzes,

and aie more plainly adze-like in shape than those of the first type.

Both forms grade into each other.

One incomplete specimen of the second type bears a longitudinal groove

on the flat side, extending to within nearly 2‘50 inches of the cutting

edge (Fig. 46). I have never before seen a groove thus cut on a Nova

Scotian implement of this kind. It may have been intended to lodge the

crooked portion of a handle, thus gaining greater firmness, or possibly

it once extended so as to form a gouge at the missing end, as remarkably

instanced in two gouges, referred to hereafter. The latter explanation,

however, does not seem probable. It may be that the tapered end or butt

having been broken off, the groove was formed in order to again haft the

remaining part in the manner just suggested ; otherwise the re-hafted

fragment would doubtless have slipped in its lashings. A short

transverse groove, however, would have answered the purpose, and

probably could have been more easily made.

A well-formed specimen (Fig. 47) of the second type, proportionately

broader than other implements of the kind, has a boss near the middle of

the convex side, which would help to retain the lashing in place. At the

point of the butt there is a slight prominence for the same purpose.

This is additional evidence of the adze method of hafting. An implement

of the first or broader type, exhibits a similar knob on the same side,

near the butt (Fig. 22). A gouge (Fig 63) in the collection also has two

well-defined bosses, one near the butt and the other near the middle.

One or two other gouges have slightly raised transverse ridges for the

same purpose. This indicates that some form of gouges, at least, were

hafted like adzes.

A couple of implements resembling the second type, are somewhat

rectangular in transverse section (Figs. 49 and 50). A thin celt, 6

inches long and ’65 of an inch thick, shown in Fig. 51, was possibly

used as a chisel. Two other specimens (Figs. 53 and 54), measuring

respectively 1125 and 12 inches, are very rough. One palaeolithic in

appearance, is merely chipped into form. The other (Fig. 53) is

doubtless a natural form, and would have been rejected from the present

account were it not for indications that the larger end had been

artificially brought

to nn edge. These two implements may belong to an older period than

those of finer workmanship. Attention has recently been drawn to

supposed evidences of n palaeolithic age in America, and Prof. Thomas

Wilson of tho Smithsonian Institution has dealt with the subject in a

paper entitled “Results of an Encpiiry as to the existence of Man in

North America during the Paleolithic Period of the Stone Age” (Report U.

S. National Museum, 1887-88) which has been referred to on a previous

page. Collectors in Nova Scotia should search closely for the ruder

forms of implements, which from their apparently unwrought appearance

may have hitherto escaped notice.

The collection contains an interesting implement which possibly is an

adze (Fig. 55). It measures 10'50 inches in length, 2 50 inches in

breadth near the cutting edge, and 2T5 at the butt, and its greatest

thickness is about 1’70. It is elliptical in section ; and does not

appear to be noticeably more fiat on one side than on the other. The

cutting edge is battered and very dull, and the butt is somewhat

shattered from a blow. What makes it particularly remarkable, is a

slight groove which encircles it entirely, a little more than six inches

from the cutting edge. Just above the groove are two prominences or

shoulders, one on each lateral edge of the tool, and from thence to the

butt the edge is slightly hollowed; all of which would assist in the

attachment of a handle. I do not remember ever to have seen a similar

example from Nova Scotia. It forms a link between the celt or adze and

the ordinary grooved axe.

Besides the celts or adzes in tho collection just referred to, some

other undescribed examples which have come to my notice may be here

described.

The McCulloch collection contains eight specimens(Figs.84,85, 87-92),

all presumably from this province. Two (Figs. 89 and 90) are

fragmentary, the rest entire. About five of them (respectively 10-50, 9

50, 7, G, and 475 inches in length) may be likened to the first or

broader type (Figs. 84-85, 87-88, 92). One of these (475 x 2 25 inches),

showing the transition to the grooved axe, is slightly indented on the

two lateral edges midway in the length (Fig. 12). This was for the

purpose of holding the lashing which hound tho haft adze who agrees in

size and shape with a syenite implement in the Pro .end Museum, a

description of which will be found in a previous paper. The adze-like

form is more or less noticeable in the specimens in the McCulloch

collection. It is difficult to decide to which typo the two fragments

belong. Thu collection also contains an extremely small and frail “celt”

(Fig. 91)—the most slightly proportioned ono which I have seen. It is n

t quite 4 25 inches long, an inch in greatest breadth, and 50 of an inch

in greatest thickness. Its form is very symmetrical. Possibly it was

intended for the use of a child, or else for some finer work than that

for which the larger tools were adapted. In the Fairbanks collection,

the shortest complete specimen, which is distinctly of the second type,

measures a little more than 525 inches in length (Fig. 35). An implement

(Fig. SG), eight inches in length, found near Margarie, Cape Breton, has

been shown to me by E.C. Fairbanks, Esq., of Halifax. It is evidently an

adze, and belongs to the broader form.

From my examinations of Dr. Patterson’s large collection in the museum

of Dalhousie College,]: I find that nearly every so-called celt or axe

therein, exhibits, more or less distinctly, one side which is

intentionally more convex or rounded than the other ; which, with other

occasional indications, tends to raise a suspicion that they had been

used as adzes. An adze (No. 40) in that collection, labelled a “stone

axe, Middle River Pt., Pietou Co.” (length 9'50 inches, greatest breadth

2G5), still retains the worn places, on the Hatter side, made by contact

with the adze-luindle. Indications of this are also to be found in other

instances. No. 53 in the same collection, labelled a “celt or chief,” is

nearly Hat on one side, while around tho other side is a depression or

shallow groove wherein where lodged the thongs which hound it to an adzo-haft.

In nearly every case tho cutting edge is more or less rounded; very

rarely is it nearly straight. Indications of the prevalence of the

adze-form of tool, are very frequent, and in many cases they leave not a

doubt as to how the implement was used. In an axe or hatchet the flat

side would have little or no advantage, except that it would allow the

tool to lie closer to the wood in making cuts in one direction.

Chisels.—There is no implement before me which I care so to designate,

although one thin celt, before mentioned, might be so considered by some

(Fig. 51). It seems doubtful whether our Indians ever used an implement

in the manner in which we handle a chisel. A limited implement for

striking blows would be far more useful to a savage people.

Gouges.—Dr. Ran, in his description of the archaeological collection of

the U. S. National Museum, says that these implements occur in the

United States far less frequently than the celts, and that they appear

to be chiefly confined to the Atlantic States. The latter circumstance

suggests that the work in which they were employed, was principally

necessary or possible in the country bordering tho eastern coast. They

may have been used in making canoes, but we would then expect to find

them abundant on the Pacific Coast, unless another implement was there

applied to the purpose, which is quite likely. Their employment by

certain tribes may account for their more frequent occurrence in

particular parts of the continent. Of course it is not probable that all

gouges were put to the same use. Doubtless many of them, perhaps even

all, were hafted adzewise, and employed in forming hollows in wood which

had previously been charred by fire and so rendered capable of being

worked by such fragile tools. They would thus he useful in making wooden

canoes, or in fashioning various utensils from the same material. I

cannot agree with those who consider that some of these

easily-destructible implements (those with the groove from end to end)

were employed in tapping and gathering the sap of the rock maple. Surely

tho axes or adzes were well adapted to making the requisite incision in

tho hark, and this having been done, a piece of birch-hark, always

available, was without doubt employed to conduct the fluid so it .should

fall into a receptacle beneath. Dr. Gilpin also was mistaken in

supposing that gouges, etc., were used in making arrow-heads. We must

never lose sight of the fact that tho Indian had a fragile material from

which to form his tools, and he had therefore to handle them with much

care. The fair, and frequently very excellent state of preservation in

which we find tho edge of most cutting implements, shows that they were

not often taxed beyond their strength.

Seventeen gouges are in the Fairbanks collection (Figs. 56-72). in

length the perfect specimens vary from 5.50 to 10,50 inches. With

perhaps one or two exceptions, nil taper more or less toward the

extremity furthest from the crescent-shaped edge. The one which most

plainly exhibits this tapered form, measures 2 inches in width near the

latter edge, and thence tapers regularly to a small rounded end at the

other extremity; its total length being 650 inches (Fig. 63). These

implements are often of noticeable symmetry, and probably were once

well-polished. They are 1‘oimed of stones of only moderate hardness.

The extent of the groove which gives them their characteristic form,

varies much. Such variations, doubtless indicate different uses to which

the tool was to be put.

In some, the groove is almost entirely indistinguishable and confined to

the vicinity of the cutting edge. They thus pass gradually into the

adze-form, which this tool otherwise greatly resembles. Three or four of

the gouges before me, are of this unpronounced shape (Figs. 56-58, 6O).

They vary from 8.50 to a little more than 6 inches in length.

Six specimens have the groove extending about half the length (Figs. 59,

61-65). They vary from 6 to 10 50 inches in length. Another specimen of

this kind is in my own collection, and was found at Waverley, near

Dartmouth, by Mr. Skerry (Fig. 94). It, together with three of the six

just mentioned, are wide and exhibit a very deep, broad groove. Another,

narrow and 0 inches long, is very interesting (Fig. 04). Although the

groove is quite evident and extends for half the length, yet the end of

the tool hears no cutting edge, that portion being blunt. The other

extremity, however, has boon rubbed into a narrow adze-like edge. The

implement may ho a disabled gouge which had been altered into an adze;

the gouge groove, having been utilized as a convenient resting place for

the T-shaped portion of a handle, which was then whipped round with

thongs. Or possibly the groove may have been intentionally made in order

to assist in maintaining the position of the haft. Another specimen

(Fig. 05) much resembles the one just described, but the gouge-edge is

less blunt. Both may have been limited in the middle like a modern

pick-axe, and so used both as a gouge and and as an adze; but this is

not probable. As a slick-stone for dressing skins, the combination of

two forms would not bo without advantage. The fragment of an adze-like

implement (Fig. 40) which has been referred to in my description of

polished stone hatchets and adzes, resembles tho two tools I have just

noticed, inasmuch as although the edge is undoubtedly adze-like in

shape, yet the upper portion of the fragment boars a shallow but

distinct groove. Among the specimens in the cabinet of the Canadian

Institute, Toronto, is an implement having a gouge at one extremity and

a chisel at the other. It was found in Simcoe County, Ontario, and will

be found figured in the report of the Institute for 1891, page 38.

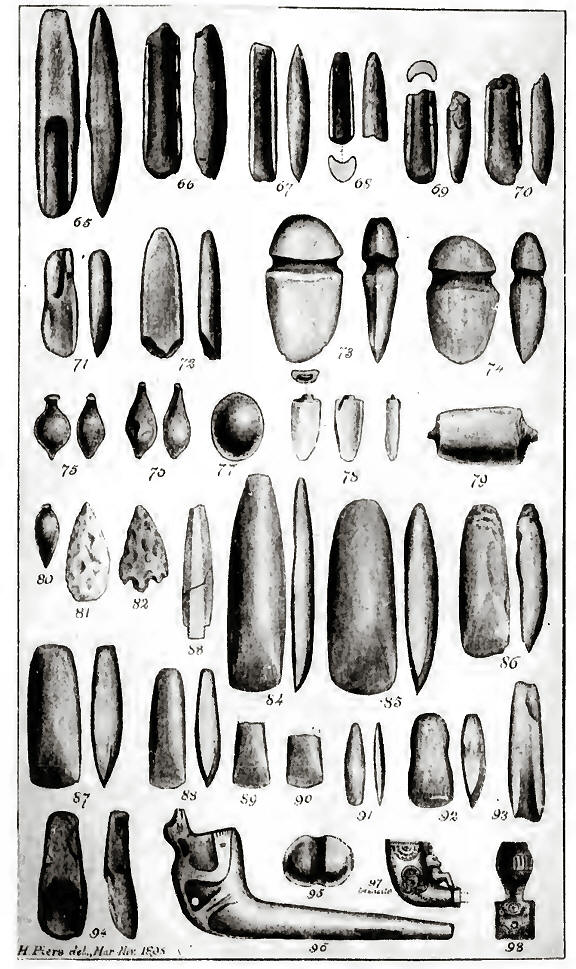

An examination of at least three gouges (Figs. 01, 03, 94,) of the

second or half-grooved form, puts it beyond doubt that these three were

hafted like adzes, with the concavity facing the user. My own specimen

(Fig. 94) from Waverley shows plainly on the convex side two ridges for

retaining the lashing, and another (Fig. 03), well proportioned,

exhibits two prominent nodules for the same purpose. One or two

adze-like “colts” bear similar nodules (Figs. 47 and 22). Probably many

other gouges were thus liffted. Without doubt it was the most reasonable

method of handling these tools when delivering excavating blows.

We shall now pass to those gouges in which the groove extends throughout

the entire length. Five well-defined examples (Figs. G6-70) are in the

Fairbanks collection, together with two (Figs. 71, 72) which arc rough

and very poorly formed. The groove varies in depth from about OH of an

inch (Fig. 72) to more than .50 of an inch (Fig. 60), and in width from

a little over '75 to nearly 1'50, Three of the five well-formed examples

are fragmentary, having been transversely broken near the middle. The

adze-like manner of hafting would not be quite so well adapted to this

particular form.

Grooved Axes.—These implements are rarely found in Nova Scotia. Dr.

Patterson has succeeded in obtaining but one specimen (7'2o inches long

by 3 25 wide) which was discovered at St. Mary’s, Guysborough County.

Two examples are in the Provincial Museum, Halifax, and have been

previously described. One of them is double grooved. In this respect it

is probably unique in Nova Scotia. The second groove was very likely

formed in order to shift the haft and so improve the balance of a faulty

implement. These, together with the examples which I am about to

describe, are all which have come to my notice in Nova Scotia. It is

quite possible that they were only introduced through trade with other

tribes or as trophies of war. They are also rare in Ontario as compared

with Ohio, Kentucky, and some neighbouring states. Dr. Bailey informs me

that of six axes in the museum of the University of New Brunswick,

Fredericton, four are grooved, and he has seen others of the same kind

in the St. John collection and elsewhere in that province.

Two well-formed, perfect specimens (Figs. 73-74) each with a single

groove, are in the Fairbanks collection. They agree in outline and

general proportions, and their form may be considered typical. The

larger one (Fig. 73) is 7 50 inches long and 4 inches in greatest width,

and weighs 491 ounces. The smaller one is 6'75 inches in length and 3'70

in greatest breadth, and weighs 40 ounces. Both appear to have been

formed from oval quartzite boulders such as are found on beaches. From

near the groove, to the edge, they are neatly “pecked” into shape, while

the whole of the butt, above the groove, is smooth, being evidently the

original surface of the boulder. The aboriginal worker in stone, was

doubtless always ready to take advantage of such material as nature had

already partially shaped, thus lessening his labour. The edges do not

show signs of rough usage. The butt of the smaller one is intact, but

that of the larger hears the marks of many light blows which probably

were the result of its use in cracking hones in order to extract the

marrow.

These axes could have been employed in detaching birch bark and in

girdling trees and so killing them preparatory to felling them by the

aid of fire, the axe being again used in order to remove the charcoal as

it formed. The tool would also constitute a formidable weapon.

Prehistoric man made his few implements answer as many purposes as

possible.

An axe very similar to those I have described, is figured by Dr. Rau (Archadogical

dollection of U. S. National Museum, figure 72). It was found in

Massachusetts. I have never seen a Nova Scotian axe with the groove only

on three sides, as shown by that writer in figure 73 of his work.

Hammers,—A beautiful hammer-head (Fig. 95) is in my own collection. It

is formed from an egg-slmped boulder, very slightly compressed on

opposite sides. Its length is 3'50 inches, greatest breadth 250 inches,

and its weight a little more than 19 ounces. Midway from either end, it

is entirely encircled by a “pecked” groove, which has not been smoothed

by friction. This groove was formed in order to attach a handle. Its

roughened surface would tend to increase tho hold of the haft and its

lashings, and the interposition of a piece of hide, which was quite

probable, might account for the absence of any smooth surfaces in the

groove. Each end shows distinctly the denting marks of numerous blows,

hut there are no large fractures. This condition of the ends and the

formation of the groove, are evidences of the hand of man, hut the oval

shape of the stone is the work of natural agencies, perhaps slightly

improved by the skill of the aboriginal craftsman. The implement was

probably used as a weapon in time of war, while in the peaceful

occupations of savage life, it was put to any uses to which it was

adapted.

Grooved stone hammers are very rare in Nova Scotia, in truth I do not

remember to have met with another. They are also, I believe, rare in the

neighbouring province of New Brunswick. My specimen was found in July,

1894, while the foundation was being dug for a manse, two or three rods

to the northward of St. James’s Presbyterian Church at Dartmouth. A

great number of human skeletons have been unearthed at that spot, but

after careful inquiry and personal search for anything which might serve

to identify those who are there buried, I have only succeeded in

obtaining this hammer and a linear-shaped piece of iron, 950 inches

long, which 1 think must have been a dagger-shaped implement, or

possibly7 a spear-point. A second iron relic of the same kind was

discovered, but I did not see it. The bones were from one foot to two

and a half or three feet below the surface of the ground. In one

instance I succeeded in finding the remains of a nailed wooden box or

rough coffin. It was almost entirely disintegrated and chiefly appeared

as a dark-coloured line in the soil. The grooved-hammer was found close

to one of the skulls. After a good deal of investigation, I have come to

the opinion that there is no evidence whatever to to show that this was

an Indian cemetery, except the presence of the above-mentioned relics.

Those who are buried there, are doubtless white men. The theory that

they were the victims of the massacre at Dartmouth in 1751, cannot be

maintained. Various reasons make me strongly of the belief that this

spot bears the bones of many of the Due d’Anville’s plague-stricken

followers, others of whom were interred near the shores of Bedford

Basin. For further information on this point, the reader may refer to a

footnote on page G of Mrs. Lawson’s History of Dartmouth. It is known

that the Micmacs assembled about the French camp, and the presence of an

Indian implement in the burial-ground of their allies is not to be

wondered at. The weapon may even have been placed in one of the coffins

as a savage mark of respect for the alien dead.

Pendants and Sinkers.—Two well-formed specimens of this class—one

perfect, the other nearly so—are in the Fairbanks collection (Figs.

75-70). They are both somewhat pear-shaped and much resemble plummets.

The lower extremity is pointed, and the upper end expands into a knob to

facilitate suspension. They thus resemble figure 100 in Dr. Rau’s

description of the archaeological collection of the U. S. National

Museum The larger one (Fig. 7G) is formed of dark red sandstone, and

measures four inches in length. The greatest diameter is toward the

lower end. The other is made of a dark hard stone. Its length is three

inches, and the largest part is situated about midway between the ends.

It is not so elongated as the other example. The two sides, including

the knob, are somewhat com. pressed, thus making the diameter T40 ine'

in one direction and 170 in the other.

A third “sinker” (Fig. 80) has been kindly lent me by W. C. Silver,

Esq., of Halifax. It was found in the bed of the Salmon River, adjoining

that gentleman’s property at Preston, about seven miles to the east of

Halifax. He informs mo that the place where it was discovered was an old

spawning ground. The specimen is a very beautiful and perfect one,

fashioned with great pains from a reddish stone, like sandstone,

containing small particles of mica, Its length is 325 inches, and its

greatest diameter is near the upper end or point of suspension. The

groove just below the knob at the top, is distinctly smoothened by a

thong bv means of which it must have once been suspended. The discovery

of the stone in a river, tends to strengthen the view that it had in

some way been employed in connection with fishing. Whatever may have

been its use, it shows what skilful work our Indians bestowed upon the

manufacture of some of their implements.

These so-called “plummets” or “sinkers” are very rare in Nova Scotia,

Dr. Gilpin figures one in his paper on the stone age. There are but two

in the Patterson collection: one, 375 inches long, well-shaped, with a

pointed lower end, being from Annapolis County ; the other, two inches

long, quite light in weight, with a rounded end, from Lunenburg County.

There are none in the collection in the Provincial Museum. Dr. Bailey in

his “Relics of the Stone Age in New Brunswick,” figures four or five

which had been found in that province.

It is worthy of remark that the sides of such specimens as I have

examined, exhibit more or less a tendency toward compression, as has

been already noted of one example. This slightly flattened form was

probably intentional. Dr. Patterson’s Annapolis “sinker” has been ground

down in one or two places on the side, but I have not found any others

in this condition. I may say that although all specimens are carefully

fashioned, and of the same general appearance, yet they differ much

among themselves in detail of form. In no case have I noted any with a

hole for suspension, although such would have been a more secure method

of hanging them had they been used as weights for fishing-lines.

These pear-shaped objects have long perplexed archaeologists who have

attempted to define their use. We find them variously denominated

sling-shots, sinkers for fishing-tackle, stones used in playing some

game, personal ornaments, sacred implements for performing some

religious ceremonies, plummets, spinning-weights, etc.

In a paper entitled “Charm Stones; Notes on the so-called ‘Plummets’ or

‘Sinkers,’” Dr. Lorenzo G. Yates has presented the very interesting

results of his investigation into the uses of such implements. For

reasons given in the paper, he discards all the stated theories on the

subject, except that relating vo their employment in sorcery.

A Santa Barbara Indian, California, when asked by Mr. H. W. Henshaw why

one of these stones could not have been used as a line sinker, replied

with much common sense, “ Why should we make stones like that when the

beach supplies sinkers in abundance? Our sinkers were beach stones, and

when we lost one we picked up another.”

A very old Indian chief, of the Napa tribe of California, told Dr. Yates

that the plummet-shaped objects were charm-stones, which were suspended

over the water where the Indians intended to fish. A stick fixed in the

hank, he said bore a cord which sustained the bewitched stone. In a

similar manner they were employed in order to obtain good luck while

hunting. Napa Indians also state that they were sometimes laid upon

rocks or peaks, from whence it was supposed they travelled through the

water during the night and drove the fish to favourite spots for

catching them, or in other cases, drove the game of the woods to the

most advantageous hunting grounds.

Other Indians of California say they were medicinal stones, and describe

the method in which they were used by sorcerers for curing the sick,

bringing rain, extinguishing fires, calling fish up the streams, and for

performing ceremonies preparatory to war. A perforated stone was said to

make its wearer impervious to arrows.

The above statements may help us to form our own opinion as to the use

of these very curious stones in Nova Scotia. Many still hold to the

belief that they were sinkers, but most of the evidence seems to be

against that theory.

Pipes.—Smoking utensils are somewhat rare in Nova Scotian archaeological

collections. Only three complete examples, and one in course of

construction, are among Dr. Patterson’s specimens in the museum of

Dalhousie College. Four are in the cases of the Provincial Museum,

Halifax, and will be found described in a previous paper by the writer.

One of these is probably of European manufacture. Dr. Bailey mentions

but a single specimen in his article on the stone-age in New Brunswick.

The Fairbanks collection, as now before me, contains no example.

Hon. W. J. Ahnon, M. D., of Halifax, possesses a large, well-formed pipe

(Fig. 96), which is without doubt the most remarkable one yet found in

the Maritime Provinces. The circumstances of its discovery are as

follows. In 1870, an upturned copper kettle was unearthed by Mr. John J.

Withrow in a piece of woodland to the westward of Upper Rawdon and

within ten rods of the line of an old French trail or road from

Shubenucadie to Newport, Hants County. The kettle was about eighteen

inches or two feet under the surface. Beneath it, when lifted, were

found the stone pipe just mentioned, two iron tomahawks, five or six

iron implements about eight or nine inches long, very much rusted, and

having a slight prominence near the middle of their length, also about,

seven dozen oval blue beads ornamented with lines, etc.. each bead

nearly the size of a sparrow’s egg, and lastly a tooth which seems to

have been the curved incisor of a beaver. There were no human bones or

other indications of a burial. The five or six iron implements Mr.

Withrow thinks were knives, hut they were so corroded as to make

identification very difficult or impossible. The kettle was fifteen

inches or so in diameter and about nine inches in depth, and it had a

handle for suspension. Close to where the kettle was found, was a

hemlock, two feet in diameter. With the exception of a few of the beads,

which Mr. Withrow retained, the relics subsequently belonged to J. W.

Onseley, Esq., barrister of Windsor. Half of the beads were criven by

this gentleman to the late Judge Wilkins, the remainder are still in his

possession. Dr. Almon obtained the pipe from Mr. Onseley.

The bowl and stem of this splendid example of aboriginal skill, are

formed of one piece, thus somewhat resembling a clumsy modern clay pipe.

The intervening portion forms a curve. The most noticeable feature of

the article is a bold representation of what is undoubtedly a lizard,

placed with its ventral surface on that side of the bowl which is

farthest from the smoker. The fore and hind legs clasp the bowl, while

the long tail lies upon the lower surface of the stem. The broad head

extends upward beyond the rim of the bowl. Two dots at the extremity of

the somewhat pointed snout, represent the nostrils of the animal. The

mouth is closed, and reaches around to the side of the head, beneath the

eyes. The latter arc represented by large, well-defined, circular

cavities. Across the back of the neck appear a row of five elliptical

cavities, their greatest length being in the direction of the length of

the body. The long fore-legs are bent upwards at right angles, and the

toes rest on the sides of the bowl’s rim. Incised lines divide the

forefeet into rather long toes, seven of which are on the right foot.

The hind legs are shorter, slightly broader, and are gradually lost in

the contour of the bowl, without any indication of toes. A longitudinal

line extends from the thigh to the vicinity of the hind foot. A round

hole, about '25 of an inch in diameter, is drilled from side to side of

the bowl, at the ventral surface of the lizard and just anterior to the

hind-legs. This hole was doubtless for fastening the pipe, by a thong,

to the smoker’s dress, in order to prevent its being lost or broken; or

else for the attachment of an ornament. The rim of the bowl is decorated

oil top by groups of from four to seven incised radiating lines. The

eavity for the reception of the narcotic is nearly circular, and is an

inch in diameter. It gradually tapers downward for about an inch and a

half, where it is somewhat suddenly constricted to nea-ly the size of a

lead pencil, after which it extends nearly an inch further downward

until it meets the perforation of the stem at a little more than a right

angle. The total depth of the cavity, therefore, would be nearly two and

a half inches. One side of the cavity is continuous with the throat of

the lizard.

The length of the stem from the extremity to the edge of the bowl

nearest the smoker, is about five inches. Its diameter at the mouth

piece is '40 of an inch ; and at the further portion, near the bowl, a

trifle more than an inch. The diameter of the perforation at the

mouth-end is '2S of an inch. The bowl rises 1'80 inch above the stem.

The thickness of the bowl at the thinnest part, is about ‘17 of an inch.

Taken generally, the whole pipe may be said to be about seven inches

long, but from the mouthpiece to the tips of the figure’s snout, it

measures 7.60 inches.

The entire specimen is in a very excellent state of preserve tion, and

without a flaw. It is formed of a fine gray stone* different from any

found in the province, and closely resembling the material of the

remarkable stone tubes in the Provincial Museum (Vide “Aboriginal

Remains of Nova Scotia Travs. N. S. I. W. S., vol. vii.) It bears a fine

polish. I did not observe any tooth-marks upon the stem, as would

probably have been the case hail it always been placed in the mouth

without some protective material. A short tube of wood may have

originally served as a mouth-piece.

It is a unique specimen in this part of the Dominion. I consider it

almost beyond question that it is not the work of Micmacs, but probably

came into Nova Scotia as a trophy of war or else by trade with some

distant tribe. The stone tubes, just mentioned, probably owe their

presence here to tho same agency. Trade was not uncommon among the

prehistoric tribes, and Lesearbot mentions that our Micmacs, or

Souriquois as ho called them, greatly esteemed the sittings of shell

beads, which came unto them from the Armouchiquois country, or the land

of the New England Indians, and they bought them “very dear.” Tobacco

itself must have been obtained by trading with nations by whom it was

cultivated.

Strange to say, in Dr. Rau’s account of the collection of the U. S.

National Museum (cut 192) is figured a pipe about four and a, half

inches long, which bears an extremely close resemblance to the Nova

Scotian specimen, both in the attitude of the animal upon it and in

general shape. Apparently, however, it is much less boldly carved. It

was found in Pennsylvania, and is described by Dr. Ran as a very

beautiful, highly polished steatite pipe, carved in imitation of a

lizard, the straight neck or stem forming the animal’s tail, and its

toes being indicated by incised lines. The similarity between the two

specimens is therefore remarkably pronounced.

Mr. David Boyle, in the report of the Canadian Institute (session 1801,

page 29), figures a similar pipe found in a grave in the Lake Baptiste

burying-giound, Ontario. Mr. Boyle speaks of it as exceedingly rare. It

is made of a soft “white-stone.” The animal whoso form extends above the

howl and more than half-way along the stem, he considers was probably

intended to represent a lizard.

Mr. Boyle also figures another pipe (Report Canadian Institute, session

1886-7, page 29,) which may he likened to our specimen, although the

resemblance, owing to the different position of the figure and the

absence of a distinct bowl and stem, is not nearly so grout as in the

two instances we have just given. It was discovered at Milton, Halton

County, Ontario. The material of which it is formed is a light-grey

stone, very soft and porous, containing minute specks, probably

micaceous, and (pute unlike anything in the geological formation of that

province. The cavities on the body and long tail, resemble those on the

neck of the Nova Scotian specimen they are probably intended to

represent spots of colour such as the aboriginal artist had open on the

animal he imitated. Several lizaids hear clearly-defined spots of bright

colour upon their bodies. Notwithstanding the length of the snout, Mr.

Bovle thought that the resemblance of the head to that of a monkey was

very striking. I am rather of the opinion that, like the figures on

other pipes mentioned, the carving was intended to represent a lizard.

Dr. Alnion possesses another stone pipe (Fig. 98), which, although most

beautifully ornainented and very symmetrical in outline, is nevertheless

of secondary interest, for the reason that it is doubtless of

comparatively modern manufacture. It was purchased from a Micmac on the

Dartmouth ferry-steamer. In general appearance it closely resembles one

found at Dartmouth in January, 1870, described by me in a paper on the

aboriginal remains in the Provincial Museum (page 287), or another from

River Dennis, Cape Breton, which is figured in the plate appended

thereto. This form is considered by Dr. Patterson to be the typical one

adopted by our Indians. The bowl, somewhat barrel-shaped, rises from a

base, laterally flattened. In the present specimen, this battened base

or keel, when viewed sideways, is square, not lobed, in outline, and

below the centre it contains a round bole for the suspension of an

ornament or to facilitate attachment to the owner’s dress by means of a

thong. The bowl and keel are most tastefully ornamented with single and

double straight lines, dots, very short diagonal dashes, and

conventional branches of foliage, all arranged in neat designs which

entitle the carver to much credit for his excellent work. I have never

seen a more comely Micmac pipe. The style of ornamentation much

resembles that of a very graceful pipe of fine argillite which belongs

to my father, Henry Piers, Esq. This, for the sake of comparison, I have

illustrated in Fig. 07. It is made by a Maliseet Indian of New Brunswick

and bears the date March 5th, 1850. The figure on the fore part of tho

bowl is excellently carved, and represents a long-haired Indian, seated,

with arms across his breast. The other decorations manifest much taste

on the part of their swarthy the signer.

Dr. Almon’s specimen, last referred to, is made of a blackish stone,

probably a close grained argillite. The total length is nearly 2.0

inches; and the height of bowl, 1.40. It is in a fine state of

preservation, and everything seems to indicate that it was formed with

modern metal tools. Possibly it is not a century old.

Dr. Almon’s lizard pipe and the Hat-based specimen from Musquodoboit in

the Provincial Museum, are the most interesting examples of this class I

have yet see?) in our province. Neither, however, are to be considered

as typically Micmac.

Three specimens, which cannot be treated under any of the preceding

heads, yet remain to be described. A singular, roller-shaped object,

presumably of aboriginal workmanship, which I find in the McCulloch

collection, is shown in Fig. 79. The ends have evidently been cut off

while the stone was rotating. Another curious object (Fig. 78) is in the

Fairbanks collection. One face thereof is slightly bowed, while the

other is correspondingly convex. The wider end has been partially cut

away so as to leave a short neck. I shall not venture an opinion as to

the use of these two relics. An oval boulder (Fig. 77), very regular in

shape, is in the same collection. Not the slightest importance, however,

can bo attached to it, for it is merely a natural form bearing no marks

of man’s workmanship.

|