|

WE have already seen that up until this

date the early settlers depended almost entirely for their living upon

the produce of their farms. The lumbering industry had barely begun, it

being confined for the most part to the sale of squared pine timber

which found a good market in the Old Country. For instance, in 1802,

when Waugh was in Scotland he had a vessel load sent across. Included in

this cargo were some sticks 52 to 56 feet long and 18 inches square.

This square timber in those days was sold by the ton, so that we find

Waugh ordering “One hundred tons of square pine timber, twenty tons of

hardwood consisting of black birch and maple, oak staves, three dozen

hand spokes and twenty or thirty pieces of yellow pine.” But the middle

“twenties” saw a great change in the industrial life of the community,

for it was then that the shipbuilding industry began, an industry which

for the next fifty y'ears was to be the main stay of the community.

The first registered ship of any description to be built at Tatamagouche,

was the “Fish Hawk”, a small schooner of 16 tons. She was built by James

Chambers and launched on the 1st of May, 1818. This was a small and

modest beginning of the industry which for the next half-century was to

mean much to the people of Tatamagouche. Closely following Chambers in

the business came Alex. McNab of Maiagash who, on November 12th of the

same year launched the “Mary” a schooner of 32 tons. For the next four

years no further ships were built here, but in 1823 the “Dapper,” 22

tons; “Nancy,” 73 tons; and “Lilly,” 28 tons were built by Thomas

Langille, Fred Hayman, and Murray and Samuel Waugh respectively'. These

men all built for personal use in the coasting trade.

But the real founder of the shipbuilding industry at Tatamagouche was

the late Hon. Alexander Campbell, who was the eldest son of William

Campbell, the half-brother of Wellwood Waugh. He was born at Pictou, and

as a young man came to Tatamagouche, first as a clerk for Mortimer and

Smith of Pictou, but in a few years he began business for himself. No

place had at that time better natural advantages for the carrying on of

this industry than Tatamagouche. The two rivers made it particularly

easy to transport from the interior the timber necessary for the

construction of the vessels, and on the shores of rivers and harbours

were to be found many suitable sites for the yards. Then, at that time

there was plenty of labour, for in the vicinity were many able-bodied

men who failed to get the expected returns from farming and welcomed,

indeed prayed for steady employment such as could be had in a shipyard.

Campbell selected a site for his shipyard on the west bank of French

River just above its junction with Waugh’s River. There, in 1824, he

built his first vessel, the “Elizabeth”, a good sized schooner of 91

tons. Three years later, with his partners, he launched the first brig

to be built at Tatamagouche. This was the “Devron” of 281 tons register.

The first vessels constructed in Nova Scotia for the English market were

nearly all large ones, varying from 125 to 700 tons. As a rule, these

were sold outright, the builders seldom, if ever, retaining a share.

Often the vessel remained long unsold in the English market. In the

meanwhile, expenses accumulated so that frequently the returns did not

equal the expenditures. Campbell, however, who had commenced on a small

scale, was always able to keep his business running and make good

profits besides. At one time, after a most successful year, a friend of

his urged him to retire from the business before he met with the severe

losses which seemed bound to overtake all who remained long in this

uncertain industry. Campbell agreed with the wisdom of the suggestion

but added, “What will happen to the room I now employ?” Campbell’s words

were only too true. The people, lured by the prospect of steady

employment, had quickly abandoned the farms which through many

sacrifices they had brought into a state of cultivation. These soon “ran

out,” and it would be years before they could be brought back to their

former degree of fertility. A sudden collapse of the shipbuilding

industry would have brought poverty and suffering to almost every family

in the community. Years after, its gradual decline was accompanied with

much hardship to those who for years had looked to it as a means of

livelihood.

Campbell’s first house was a log one and was situated in what is now the

field of Gordon Clark, close by the railway cut. After his marriage he

removed to his new house where Gavin Clark now resides. He early

attained a position of great wealth and influence in Tatamagouche.

Besides being the employer of many men, he had the local management of

the DesBarres estate, from which, as early as 1837, he had purchased no

less than 2,500 acres of the very best land. He died in 1854 at the

comparatively early age of fifty-nine. A number of years before his

death he had been appointed a member of the Legislative Council and it

was on his return from attending its session at Halifax that he was

stricken with an illness which at once proved fatal. Honest in his

dealings, sound in his judgment, endowed with great natural ability, and

possessing a commanding personality, he was for years the foremost man

in Tatamagouche. Born when the struggle for a bare living was still a

keen one, education found but a small place in his boyhood days. At an

early age he was obliged to work for himself. He thus obtained in

“life’s rough school’’ the training which fitted him to take a most

successful and prominent part in the development of this country. Of his

early days at Tatamagouche, we know but little. A log house was the

first home of the man who subsequently was to count his dollars in

thousands, his lands in square miles and who, during his business career

of thirty years, shipped millions of feet of lumber and built over one

hundred vessels. Within fifteen years after he came to Tatamagouche he

was a wealthy man. He became the possessor of valuable tracts of timber

from which he sold each year large quantities of lumber. From his

shipyards, in which he employed about one hundred men, he launched

annually three or four vessels. As the years went by his wealth and

influence increased. During the “forties” he built each year five or six

vessels. The number of men whom he employed had increased to two

hundred. He was the local magnate of the community and throughout the

whole countryside his word, to a great extent was law. The “fifties” saw

his influence undiminished. Strong physically as he was, the anxieties

and the worries of the treacherous business in which he was engaged were

making themselves felt upon his robust constitution and at the close of

the session of the Legislature in 1854 he returned home only to be

stricken with a fatal illness. It is over sixty years since he passed

away. Men of seventy-five remember him but slightly, yet his name is as

familiar as if he had died only a score of years ago. This is because of

the great position of influence which he held and because of a strong

personality which so impressed itself upon those with whom he came in

contact that his name still lives. His likeness shows him to have been a

man possessing vigor, determination, independence and kindliness.

Indeed, it was for these qualities that he was especially known. As a

business man he was remarkably successful. Financial crises which could

neither be foreseen nor prevented ruined many of the shipbuilders of

Nova Scotia but through them all he steadily increased in wealth On

several occasions, particularly in the last year of his life he suffered

losses which lessened his wealth materially but even then he died a

wealthy man. In public matters the people looked to him for leadership.

Hence his friendship and support were wooed by the politicians of his

day. That at times he used his position of influence in arbitrarily

carrying out his wishes in public matters there seems but little doubt.

But compared with the invaluable services which he rendered his

community and, indeed his province, his public indiscretions are as dust

.n the balance. It was his honour to be a member of the highest branch

of a Legislature which was then performing duties fraught with the

gravest responsibilities. To have been called to sit in this body during

the strenuous times of seventy years ago and to have had a hand in the

governing of this province during one of the most momentous periods of

its history was an honour that could only come to a man of marked

ability.

Mrs. Campbell, before her marriage, was Mary Archibald, a daughter of

Colonel David Archibald,- who was a grandson of David Archibald, one of

the pioneer settlers of Truro and the first to represent that district

in the House of Assembly. She died in 1894 at the advanced age of

eighty-four. She was a most remarkable woman and for years was the

leader in all good works in the community. In the early days she

suffered many hardships and discomforts. On one occasion she rode to

Truro on horseback, carrying; her eldest child (Mrs. Patterson), then a

mere infant, with her. She was kind and hospitable and there are few of

the old people but can say that they have on various occasions

experienced her kindness. In their family were four sons: David, George,

Archibald, and William, and four daughters: Elizabeth (Mrs. Archibald

Patterson), Margaret (Mrs Archibald), Hannah (Mrs. John S. McLean), and

Olivia (Mrs. Howard Primrose). David and Archibald continued in their

father’s business until their deaths in 1887 and 1891 respectively.

Besides being leaders in the business activity of the place, they took

leading parts m ail matters of public interest. Archie was an elder in

the Tatamagouche Presbyterian congregation. George was a member of the

legal profession and until his death in 1897 practised in Truro. William

died as a young man. Of this family, the eldest, Mrs. Patterson, alone

survives, now (1917) in the ninety-second year of her age. For years she

lived at Halifax with Mrs. McLean, whose husband, in his life time, had

been President of the Bank of Nova Scotia.

Campbell was soon followed to Tatamagouche by others who, like himself,

engaged in the shipbuilding industry. Among the first to join him were

his two brothers, William and James. The former had his shipyard on the

east bank of the French River, near McCully’s. The ruins of his old

wharf may still be seen. About 1810 he retired from the business and

devoted himself to farming. He was afterwards appointed Customs

Collector at this port, which position he held until a few years of his

death. He was married to Olivia, daughter of Dr. Upham of Onslow and

grand-daughter of Judge Upham of New Brunswick. They had a family of

four daughters: Mary, who was a teacher m the public schools at Pictou;

Jessie and Margaret, Mho lived on the old homestead; and Bessie (Mrs. W.

A. Patterson). William Campbell died in 1878 and his wife in 1847.

James Campbell lived where James Ramsey now resides and continued from

1831 until 1841 as one of the shipbuilders of Tatamagouche. He died in

1855. His shipyard was near where Bonyman’s factory now stands. One of

his ships, the “Colchester”, was at the time (1833) the largest ship to

be built in the county, and attracted much attention, many coming from

Truro and other places to see her launched. Campbell represented North

Colchester in the House of Assembly for one Parliament, 1851-5. In this

closely contested election he has opposed by the late Judge Munroe. His

wife was Elizabeth Baxter. They had three daughters: Martha (Mrs.

Laird), Eliza (Mrs. Poole,) and Lavinia (Mrs. Daniel Barclay), and two

sons: William and James A. G. William died as a young man. James

succeeded Robert Logan as Collector of Customs and held that position

till his death in 1905.

On October 27th, 1824, Coionel DesBarres died at Poplar Grove, Halifax.

We have already noted his career till the close of the Seven Years’ War

in 1763. An engineer by profession, he engaged himself for the next ten

years in preparing charts of the Nova Scotia coast, some of which are of

the greatest repute. Afterwards he extended his labours and prepared a

more extensive one of North America.

DesBarres, so it is believed, did not consider himself amply rewarded

for his many valuable services to his country. It is true that he

secured grants of enormous tracts of land. But at that time this land as

a revenue producer was a nullity. DesBarres accordingly pressed his

claims and, in 1784, was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the newly

formed province of Cape Breton. He, in the meanwhile, had been living at

Portsmouth, England and, on the 16th day of November of that year,

landed at Halifax from whence he proceeded to Sydney where he remained

till 1804. His stay at Sydney was characterised by violent quarrels with

other government officials. But one thing, which should never be

forgotten, remains to his credit. One winter the settlers of Cape Breton

were in poverty-stricken conditions. DesBarres, failing to obtain proper

relief from the government, spent large sums of his own money in

alleviating the sufferings of the people, and at a time when his own

financial standing was none too sound. In 1805, he was appointed

Governor of Prince Edward Island, which office he held until 1813. While

holding these positions of honour, which required a large outlay of

money, with a comparatively small income, DesBarres was continually in

need of money and determined that his vast estates should furnish him

the necessary amounts. So that, as his financial difficulties increased,

so did the discontent of his Tatamagouche tenants, many of whom, as we

have already seen, left and settled in River John.

DesBarres, in order to prevent the loss of all his tenants, began

granting freehold deeds, but only in a limited number, so that up till

as late as 1820 the number of land owners at Tatamagouche did not exceed

half a score.

He frequently visited Tatamagouche. According to one writer, he found it

a quiet retreat when hard pressed by his creditors. Though the following

incident can hardly be said to have any connection with the history of

Tatamagouche, we think it well worth repeating:

“He and General Haldimand were great friends. They carried on a lively

correspondence mostly in French. There is a letter in the Haldimand

papers at Ottawa which the Colonel wrote from Tatamagouche. The Colonel

wanted a small loan which he could repay. He explains that some sort of

an adventurer whom Haldimand had sent to him with letters of

introduction had victimised him to the extent of a few hundred pounds,

and impaired his credit. So seriously were DesBarri s’ affairs involved

that he had come a little hastily in order to have peace. Tnere is a

modern touch about this incidental remark.”

DesBarres continued as Governor till 1813, when he removed to Halifax,

where he spent the remaining eleven years of his life.

A strong man physically, he endured many hardships and yet lived to be

one month of one hundred and three years of age. It is related that he

celebrated to the great amusement of his friends, his one hundredth

birthday by dancing on a round table.

“It would be difficult to say how far his troubles and services oa the

battlefield shortened his life. . . Given an easy life, ne might perhaps

have completed the second century, on which he entered with good health

and extraordinary vigour. But as he could not forget his losses and mind

his griefs no more, he was cut off at the above early age.”

He was a good and brave soldier; strange that he who never feared any

foe, often fled in terror before an angry creditor. He possessed a fiery

temper. On one occasion, when judgment had been given against him in

Court, he, on the spur of the moment, resulted the Chief Justice,

Jonathan Belcher. For this offence he was severely reprimanded by the

Governor and Council, and forced to apologise. He did so in an evasive

way which, however, seemed to satisfy the Court and Council.

The following is an account of his funeral taken from the “Acadian

Recorder” of November 6th, 1824:

FUNERAL OF THE LATE COL. DESBARRES.

“On Monday last, about three o'clock, p. m., the funeral procession left

his late residence. His Honour, the President, most of the members of

His Majesty’s Council, the gentlemen of the Bar, the officers of the

Army end Navy, and many other respectable inhabitants attended as

mourners by invitation.

“The procession was escorted by a detachment of military and the rear

was closed by a number of carriages. On arriving at St. George’s Church,

where his remains were deposited, the funeral service was impressively

read by the Rev. D. J. T. Twining, at the conclusion of which three

volleys were discharged by the troops. Although the. day was very rainy,

we have seldom seen a greater attendance or more interest excited on

such an occasion. Indeed every reflecting person must have found great

cause for meditation in the departure of this venerable man from our

fleeting and unsubstantial scene. We saw him on the day before the

internment, lying in state. His face was exposed to view, and it

exhibited unequivocal marks of a mind originally east in a strong and

inflexible mould, while the hand of time appeared to have made but a

slight impression on the features. The Chart, which he prepared frc m

his own survey of this Province, will give his memory claims upon the

gratitude of the nautical world, and could only have been produced by a

man of surprising perseverance.

We believe he was a native of Switzerland, and are informed that he held

a Captain's Commission under the great Wolfe tit the reduction of

Quebec. He was within a month of 103 years of age.”

On the death of DesBarres his son, the Honourable Augustus W., who was a

judge of the Newfoundland Bench, took over the management of his

father’s estate at Tatamagouche. We quote the following from the History

of Newfoundland by D. W. Browse:

“The Hon. Augustus DesBarres was a most correct man. . . He was so young

when he received his first appointment as Attorney General of Cape

Breton, that, by the advice of friends he wore a pair of false whiskers

when he went to receive 1 is commission. He was very celebrated for his

ready wit and repartee. Once, when the late Judge Hayward was quoting

Chitty to the Bench, his Lordship retorted, 'Obittv, Mr Havard, goodness

due. what does Mr. Chitty know about this country? He was never in

Newfoundland.’ ”

Augustus DesBarres, either to satisfy his own need for money or to

prevent the tenants from removing to other places, immediately began to

give freehold deeds to the Tatamagouche tenants. Since m many cases they

were unable to pay the agreed price, mortgages were given to DesBarres.

In the year 1828, forty-seven lots of one hundred acres each were

mortgaged back to the DesBarres estate. But the mortgages, in the course

of a few years, were released and the owners acquired an absolute title.

DesBarres, while in Newfoundland, continued to sell the land in small

lots to suit the buyers.2 Alexander Campbell was his local agent at this

place. Campbell was also a Justice of the Peace and his name in that

capacity is to be found in nearly all the early land transactions at

Tatamagouche. In 1858, DesBarres received his pension and retired from

the Bench and returned to spend the rest of his days in England. No

longer wishing to be burdened with the worries of the Tatamagouche

estate, he, in 1859, gave full power of attorney over these lands to

Charles Twining of Halifax, who appointed Samuel Waugh, Esquire, his

local agent. By this time the vast estate had greatly dwindled, but

rents continued to be collected and lands sold until every acre of the

original grant had passed into other hands. Today, DesBarres’

descendants do not lay claim to the title of a single acre of land at

Tatamagouche.

In 1826, John Nelson, at the age of twenty-one, settled at Tatamagouche.

His father came from the north of Ireland to Musquodoboit, where he

married an Archibald. John Nelson married Margaret Ilavman, daughter of

William Hayman and settled on Waugh’s River. His son David, who for many

years has been one of the leading merchants of the village, represented

both Waugh’s River and Tatamagouche in the Municipal Council, and for

six years was Warden of the County. Three other Nelson brothers also

came to Tatamagouche: Hugh, who lived where George Millar now resides;

Robert, who removed to Wallace; and David, who settled on the New Truro

Road. The last married Nellie Hayman, who, after his death married

Donald Cameron. His son John continued till his death to live on his

father’s farm.

In the same year, the Rev. Hugh Ross, who was the first Presbyterian

minister to be settled at Tatamagouche, took up his residence on that

point of land which to this day bears his name. He was a native of

Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and in 1813 came to Pictou County, where nis

father had settled at Hopewell. His wife was Flora McKay. He died in

1858, aged sixty-two years. His wife died in 1874, aged seventy-six. In

their family were: Mary Ann (Mrs. Walker); Margaret (Mrs. McGregor);

Caroline (Mrs. Irving); Isabella, who lived till her death a few years

ago on the old homestead; Flora (Mrs. Joseph Spinney) of the village;

Jessie McGregor, who for a number of years was a school teacher in New

Annan; Elizabeth (Mrs. Thornton); James; John; Peter, and Alexander.

Later on we shall deal with the work of Mr. Ross as minister- at

Tatamagouche.

About the year 1828, John Bonyman, who was a son of William Bonyman of

Rothmase, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, settled on the farm on the French

River, now owned by his grandson, William. John Bonyman was a magistrate

and one of the first elders in the Tatamagouche Presbyterian

congregation. He removed to Illinois. One of his sons, James, settled on

the Mill Brook, and another, John, on thf old homestead. A few years

after coming to Tatamagouche, he was joined by his brother, Edward from

Banffshire, who settled on the farm now owned by John Tattrie, on the

New Annan Road. John Bonyman, who erected the woodworking factory in the

village, and Alexander Bonyman, merchant, were two of his sons. About

1836, a third brother, James, settled on the farm now owned by his son,

John. The only sister to come to this country was Susan, the wife of

Robert Cooper.

James Simpson was another early settler of this district. About 1828 he

took up a farm on the hill across the river from Cooper’s where he built

his house on the very bank of the river. John Simpson is his grandson.

The census of 1827 is the first one in which Tatamagouche appears. In

the ones previous to that time, the population of Tatamagouche was

included in the return for the district of Colchester. Even in the year

1827, Tatamagouche is linked up with Earltown, so that it would be

nearer correct to say that it is a return for North Colchester, rather

than for Tatamagouche alone. The following are the returns given for

that year: Population, 1104, number of acres of land under cultivation,

2607; number of bushels of wheat, 1820; number of bushels of other

grain, 3978; number of bushels of potatoes, 37,780; number of tons of

hay, 860; number of horses, 80; number of horned cattle, 818; number of

sheep, 1113; number of swine, 788. The year 1827 was very unfavourable

to the growth of wheat and the return may be considered not more than

one-third of an average crop.

Besides the settlers and their descendants already mentioned, there were

at Tatamagouche, in 1828-9, John Smith, on Waugh’s River, near where the

late Fred Meagher, Esquire, lived; Charles Simpson; Kenneth McDonald,

trader, who had his house in the field of Gordon Clark (where you can

still see its site); Dan Hurley, who settled on the Williamson place;

John Jollimore; George Stewart, on lot 80, east side; and Samuel S.

Tupper, where the late George McConnell lived. These were all the

settlers who, up till the year 1828, had any land in this vicinity, at

least as far as the records at Truro show, but in all probability there

were others who were living here but, as yet, had acquired no interest

in any land, hence their names do not appear in the Registry of Deeds at

Truro.

About 1830, came another Scotchman, William McCully. He first lived up

the French River on the/Donaldson farm which was then owned by the Hon.

Alexander Campbell. He then lived on Ross’ Point for a while, but

finally removed to New Annan. One son, William, came to Tatamagouche,

where he lived on the hill which is still known by his name. Another

son, James is still living on the old farm in New Annan Another son,

John, also lived in New Annan. Mary (Mrs. Kenneth McLeod) was a

daughter. William, Jr., was a ship carpenter at Campbell’s.

During the “thirties” this immigration continued. In 1832, came John

Ross, a native of Rosshire, Scotland. In the old country he had served

his time as a cartwright but, hoping to improve his condition, came to

Nova Scotia and landed at Pictou, whence he came to Tatamagouche.

In Scotland he had known the Lepper family, which previously had settled

on the French River, and on arriving at Tatamagouche, he first visited

them and then went to work in Campbell’s shipyard. He eventually became

foreman but, after building one ship for him. went to work for Edward

Kent, who had commenced shipbuilding up the river near James Campbell’s.

After building two for Kent, he returned to farm life. He bought and

settled down across the river on the lot now owned by his son,

Alexander. He was soon joined by his brothers: Alexander in 1833 and

George, William, Thomas, and Hugh in 1841 Alexander settled at

Barrachois, where his sons William and Jefferson now reside, and the

last three at Waidegrave on the farms now owned by Ross Wetherbie,

William Kennedy, and Mac Ross respectively.

It was in or about the year 1832, that the first hotel was opened at

Tatamagouche. William McConnell was the proprietor and his first inn was

the building now known to us all as the “Stirling Hotel”, though since

that date it has suffered many changes and received many additions.

McConnell, who was a native of Gaiway, was a land surveyor, and before

coming to Tatamagouche lived for ten years in New Annan. At his death he

was a few years under a hundred. His wife was also a McConnell. One

daughter was the wife of the late John Ross. When he left Tatamagouche,

he was succeeded in this hospitable business first by Charles D.

McCurdy, then by a Copp from Pugwash, who was here somewhere about 1848.

Copp in turn gave way to Mrs. Talbot. After she gave up the business,

James Blair, the father of Isaac Blair, took over the charge until about

the year 1860. During the next five years this business passed through

the hands of James Morrison, the Misses Murdoch of New Annan, and Miss

Rood, who, in 1865, sold out to Archibald McKenzie from whom Timothy

McLellan, the father of the present proprietor, purchased it in 1873.

In the early “thirties”, John Hewitt came from Guys-borough to act as

foreman in the shipyards of Alex. Campbell who was then building some of

his vessels on the river below James Bryden’s. Hewitt built the

Williamson house which, until it was torn down a few years ago, was the

oldest house in the village. Subsequently he removed from Tatamagouche.

In 1834, Robert Cooper, who was a native of Aberdeenshire, obtained from

DesRarres a grant of land on the French River where his daughter, Mary,

now resides. He had two sons: James and William, who both moved away.

Ilis brother George settled with him on this farm.

John Lockerbie, who was a native of Castle

Dougias, Kirkcudbright, Scotland, came to Tatamagouche in 1835 and

settled on the farm now owned by his son, David. On this property,

previous to Lockerbie’s arrival, were two log houses. One, between the

present house and the river, was built by David Hayman, and the other,

on the bank of the river opposite the Pride place, by Thomas Henderson

Lockerbie was married in Scotland to Catherine Williamson. Two children,

John and Jane (Mrs. Robert Purves), were born there, and Margaret (Mrs.

Reid), Mary (Mrs. James Bryden), Martha Bell, Cassie (Mrs. Anderson),

David, and Ninian at Tatamagouche.

A few years afterwards came Lockerbie’s brother-law, David Williamson,

who was a descendant of Alex. Williamson*, a leading Covenanter of

Sanquharf, one of the most historic spots in Scotland and the scene of

many a conflict between the Covenanters and their oppressors.

Williamson, his wife, and two children came out in a ship named

“Burnhope Side”, which was laden with bricks for the Citadel at Halifax.

The voyage took over two months. The first person to board the ship at

Halifax was Joseph Howe, who soundly rated all those who were concerned

with the overloading of the ship. David Williamson took up his abode in

what was afterwards known as the Williamson homestead. The sturdy

independence and unfailing hospitality which characterized the

Covenanters descended in full share to Williamson, and for his kindness

and piety he was known throughout the whole countryside. He was an elder

in the Tatamagouche Presbyterian congregation. On one occasion during

family worship, his barn took fire. He left his reading and saw it burn

to the ground without being able to save it, then, returr ng to the

house, he took the books and finished prayers. His wife was Mary

Carruthers. She predeceased her husband twenty-two years, he living to

the good old age of eighty-six. Then son, Alex. Williamson died n Buenos

Ayres and a daughter, Mrs. J. W. Kent, still survives.

In 1835, the Bryden brothers, William and Robert came from Old Bains and

settled at Tatamagouche. They were both born at Maitland, and were

descendants of Robert Bryden, who was one of the Dumfries settlers of

Pictou, and who subsequently settled on the Middle River, Pictou County.

William was a blacksmith and had his place of business where Gordon

Fraser now pursues the same trade. Before purchasing what is now the

Reilly property, he lived in the old house of Alexander Campbell. His

wife was Susan Kent who, after his death, married Charles Reilly. In

their family were: James, of the village; Mary Jane (Mrs. Irvine), who

is living in the States; and Elizabeth (Mrs. McCurdy). He died in 1842,

aged thirty-four years. Robert, his brother, was also a blacksmith, his

shop being directly across from his house in the building now used by

Thomas Bonyman for the same purpose. He died in 1902. His wife was

Christina Reilly, who died in 1913 at the advanced age of ninety-four.

In their family were Charles, Elizabeth, James, Kate, Mary (Mrs.

Hathaway) and Robert. Of these the first, Charles, is a Presbyterian

minister and at present is connected with the Mission Field in the

Canadian West.

About the same time came Neil Ramsey, from Prince Edward Island. He was

a blacksmith by trade and had his house and forge in what is now the

garden of the Misses Blackwood, close to the church lot and near the

Back Street. He did a great deal of the iron work for the ships and

subsequently went, in a small measure, into shipbuilding. He afterwards

removed to the Island. James Ramsey, the present Collector of Customs,

Tatamagouche, is a son.

It was in or about the year 1837, that John Millar, of Pictou, came as a

boy of thirteen years to work as a clerk for Alexander Campbell. He was

a son of Andrew Millar of Pictou, who was a native of Edinburgh,

Scotland In the course of time he was given an interest in the busines

of his uncle, the Hon. Alex. Campbell, which now went by the name of

Campbell and Company. Subsequently he commenced a mercantile business

for himself in the village, his shop being situated at the corner of

Mein Street and the Public Lane. He built and lived his married life in

the house now owned by Miss McIntosh. Mr. Miliar, until his death in

1895, was one of the most prominent men in the village. Until its

dissolution in 1868, he was Colonel of the 6th Colchester Battalion,

Nova Scotia Militia. He was one of the representatives of Tatamagouche

in the Municipal Council and, for at least one term, was Warden of the

County. He was also a Justice of the Peace. A business man of the old

school, he introduced into whatever matter he had on hand, those rules

of punctuality which characterised the business men of that time. In

later years, when he and Henderson Gass drove on week days from their

homes to their places of business in the village, it has been said that

they were so punctual that when they opened their shops in the morning,

it was a signg.1 for the people to set their watches at eight o’clock.

He was married to Louisa Patterson, a daughter of Abram Patterson of

Pictou. Geoige, their third son, is a Presbyterian minister at Alberton,

Prince Edward Island. Alexander, their youngest son, succeeded his

father in business. He was a municipal councillor for Tatamagouche West

for one term. He is n6w residing at Sydney, N. S. Another son, William,

is engaged in railway work in the American West.

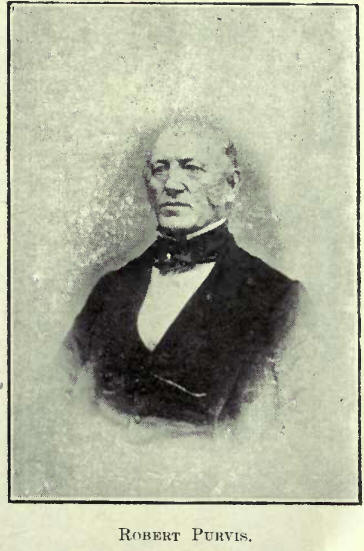

In 1837, Robert Purves came from Pictou to

engage first in lumbering and subsequently in shipbuilding. He purchased

a lot from Mortimer in 1839 and began building along the shore below

where the late W. A. Patterson subsequently lived. He also built a

vessel across the harbour on Oak Island, which then became known as

“Ship Yard” Island. His house was erected close to where the railway now

runs. After conducting business here for a number of years, he removed

to Wallace, but he subsequently returned to Tatamagouche, and built that

large residence known as “Oak Hall”, which remained the property of his

daughter, Mary, till it was purchased a year or. so ago by E. L. W.

Haskett-Smith. In his business transactions he appeared to be most

successful and, at his death in 1872, he was considered a well-off man.

His son, Robert, was for many years the postmaster in the village. He

also conducted a general stoie. A daughter, Mary, lived in the old home

till a few years ago, when she removed to Sydney, where she died In the

winter of 1916. Mrs. Wallis, in England, is another daughter.

It was in or before the year 1838 that Robert D. Cutten came from Onslow

to Tatamagouche. He was by trade both a tinsmith and sparmaker. His

first shop was in what is now the orchard of Gavin Clark. He built the

house now owned by Mrs. Robert Jollimore. He was married to Hannah Pryde.

Three of his sons, Edward, David, and William, are now residing in the

States, wheie the family removed some time in the ‘‘sixties”.

In or about the same year, John Irvine came to Tatamagouche from Pictou

to work at his trade as block-maker in the shipyard of Alexander

Campbell. His first house was built on the west side of the main road, a

little west of Mrs. Crowe’s. About this time a number of men who were

employed in the various yards built residences along this road, so that

it was commonly known as “Mechanic Street”. Subsequently Irvine built

and lived in the house now owned by Arthur Cunningham. He was accidently

killed by falling from a beam in his barn. His wife was Maysie

MacKinnon. Their family of six boys are all dead. William died of yellow

fever while on a voyage to Havana. James moved to the Southern States

where he died only a few years ago. The other members of the family were

George, Joseph, Robert, and Washington.

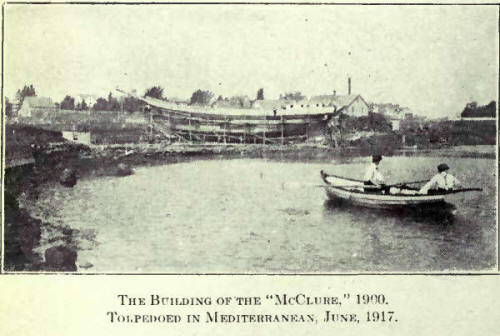

By this time the shipbuilding industry had reached almost gigantic

proportions. A hurried glance at Appendix I, which gives a list of

vessels built at Tatamagouche, will show that during the “thirties”

there were, as a rule, three or four ships, averaging 200 tons each,

built each year at Tatamagouche. The years 1836-7-8-9 were extremely

busy ones. “The Mersey”, a ship of 734 tons, built in 1837, was the

largest one at that time to be launched in North Colchester. The total

tonnage built here in 1837-9 amounted to somewhere around 5,500 tons. .

In 1840-1 there was a serious financial depression which had full effect

in Nova Scotia. Freights were low and there was little or no market for

ships. Many of the Nova Scotian builders went insolvent. At Tatamagouche

though suffering seriously they managed to weather the gale and, in a

year conditions were again normal. From that date, shipbuilding in

Tatamagouche, as elsewhere in Nova Scotia, had a new lease of life, and

during the following years, the population of Tatamagouche continued to

be increased by a number who came here either to build vessels or to

work in the yards. But before dealing with the events of these years, we

may note two or three fatal accidents which occurred in this community

sometime during the years 1830-40.

One of these took place in the year 1836 at the inn of old William

Currie. John Doull, who was one of the early settlers at Brule, had come

on horseback from Halifax, whither he had been on business, and stopped

at the inn for his dinner. After his meal, while he was endeavouring to

unhitch his horse, it kicked him on the head, causing almost immediate

death.

Another tragic death which occurred about the same time, possibly a few

years later, was that of a man by the name of Regan, who had previously

belonged to Halifax. He had been engaged in hauling logs and was

unloading them on the bank of Waugh’s River near the small creek, a

little east of where Abe Currie now resides. He had unhitched one horse

for the purpose of hauling the heavy iogs off the waggon, and while

putting the chain around a stick, the hook caught in his trousers at the

ankle. Before he could free himself, the horse took sudden fright, and

he was dragged helplessly on the ground. All his efforts to loose

himself or stop the horse were in vain, but his cries attracted the

attention of Murray Currie, a son of John Currie, who immediately ran to

the road in an endeavour to stop the horse. Before he could reach the

animal, a small dog which was with him had by barking and biting so

frightened it, that all his attempts were futile. The small brook near

McCullough’s was then crossed by a log bridge, on which repairs were

being made, and while Regan was dragged over it, a loose stick ran into

his side. The frightened animal continued to drag man and stick until it

was finally caught near where Archie Waugh now lives. The unfortunate

man's injuries were most serious and in a short time he died.

But the most shocking accident which ever occurred in the community was

the one that resulted in the death of a young child of Hector

Sutherland, an early settler, who was then living on the farm now owned

by George McKay near the Mine Hole. His house was a small log one close

to which extended the primeval forest. A short time previous to the time

of the accident, there had been a heavy wind storm which had uprooted

several of the large trees near the house. In his spare moments,

Sutherland, with the assistance of a neighbour would saw these trees

into blocks for shingles. One day while they were engaged at this work,

the child was sent bv its mother to call them to their meal. As neither

the child nor the men returned, the mother became alarmed, and, on going

to her husband, she was surprised to learn that they had neither seen

nor heard of the child. Word was at once sent to all the neighbours and

to the village, and a search party organized. Alexander Campbell, so it

is said, not only offered a large reward for the recovery of the child,

but allowed all the men in his yards to join in the search and even sent

provisions (including a good supply of rum) to the men who were

searching in the woods. No trace of the child was found and after a day

or two the search was given up, all knowing that by that time the child

would have perished from Lunger and exposure. Some time previous,

Indians had been seen in the vicinity of the Mine Hole and it was

generally believed that they were responsible for the disappearance of

the child. A few days later, other Indians, induced by the prospect of

obtaining so large a reward, and believing that some of their less

worthy brothers had been guilty of stealing the child, went as far east

as Cape Breton in search of the missing one, but they returned without

accomplishing anything. Several weeks after the mystery was cleared up,

but in a most ghastly manner. A quarrel between a cat and a dog

attracted the attention of the parents, who were surprised and shocked

to find the cause of the quarrel was none other than the hand of their

lost child. When going to call them, it had climbed up on the upturned

root of the tree on which the men were working. When it had been severed

from its trunk, its weight carrying it back, had crushed the child to

death. There the body had remained unknown to all, till the dog,

discovering it, had brought it once more to the sight of the parents.

Among others who, during the late “thirties” and the ‘forties” came to

Tatamagouche and who subsequently became some of its leading citizens,

we may note the following: James McKeen, Edward Kent, Archibald

Patterson, Charles Reilly, Robert Logan, William Fraser, and Henderson

and Robert Gass.

James McKeen was a native of St. Mary’s, Guysborough County, and came to

Tatamagouche to take over the tanning business then operated by James

Campbell and James Hepburn of Pictou. This business he conducted till

shortly before his death in 1894. He was married to Mary, a sister of

Charles Reilly. In their family were John, who was manager of the Bank

of Nova Scotia at Amherst, Ottawa and Halifax, and who in 1915 was

elected a controller of the City of Halifax; James, who is a

Presbyterian minister at Orono, Ontario; Charles, who resides on the old

homestead; and Kate, Jessie, Emily (Mrs. Maxwell), Janie (Mrs. Abram H.

Patterson), Sophia (Mrs. E. D. Roach), Elizabeth (Mrs. McGregor), Annie,

and Hannah.

Edward Kent was the grandson of James Kent, who was born in Alloa,

Scotland, in 1749. His father was John Kent who lived in Lower Stewiacke,

where Edward Kent was born in 1823. Coming to Tatamagouche, he engaged

in blacksmithing first, then in shipbuilding and other mercantile

business. He erected the house now owned by Dr. Murray. In 1851, he

built his first vessel, the “Little Pet”, which was launched up the

river below where Abe Currie now lives. After this, until shortly before

his death in 1870, he continued at the same business. His wife was

Jessie Williamson, who still survives. In his family were David, of the

village; James, in the States; Roach and Alex, in California; Mary (Mrs.

Ingraham); Jeanette; Florence, who was a distinguished actress; Jessie;

and Janie Bell.

Archibald Patterson was a grandson of John Patterson, who was one of the

Pictou pioneers of the “Hector” His father was Abram Patterson, of the

same place. He first came to Tatamagouche and engaged in trading in

lumber and other business, but it was not till 1854 that he built in his

shipyards, where Bonvman’s factory now stands, his first vessel, the

“MacDuff. In 1862, Patterson was appointed a member of the Legislative

Council, a position which he held till Confederation. In 1868 he retired

from business in Tatamagouche and moved to Halifax where he was

Inspector in the Inland Revenue Department. He was married to Elizabeth,

the eldest daughter of the Hon. Alexander Campbell. Mrs. Patterson is

now living in Truro.

A. C. Patterson who, till his death in 1913, was a barrister in Truro,

was a son. Mrs. J. W. Revere was a daughter.

Charles Reilly, of Irish descent, came from Pictou to Tatamagouche and

worked for a while in Campbell’s tannery. His first house was a small

one built in the front of what is now the house lot of C. K. McLellan.

For a number of years he lived there with his sisters until they were

married to James McKeen, Robert Bryden, and James McLearn Reilly was

married to Susan Kent, the widow of William Bryden. Subsequently he

lived on the property now owned by his daughters Misses Annie and Sarah.

Here, till his death, he carried on his trade as a butcher. He was for a

short time in the shipbuilding business and built a few vessels on the

river below where James Bryden now resides. William Reilly, of the

village, is his only surviving son. Another son, John, died in the

States only a year or so ago.

Robert Logan came to Tatamagouche from New Glasgow and was employed for

a number of years as clerk for William Campbell. He became interested in

shipbuilding and built for a number of years on the river a little below

Clark’s wharf. After retiring from business, he was appointed Collector

of Customs at this port. His wife was Mary Bryden, sister of Robert

Bryden. One son, Capt. William, died at sea from an attack of yellow

fever. Another son, Robert, and a daughter, Anna Bell, are now living in

Bridgewater, Nova Scotia.

In 1840, William Fraser, of Pictou, built here a brig, “James”, for

James Cameron of Halifax. In a few years he became foreman for the Hon.

Alex. Campbell and after Campbell’s death he continued to act in that

capacity for the firm till shipbuilding at Tatamagouche was of the past.

He built and lived in the house in Mechanic Street which is now owned by

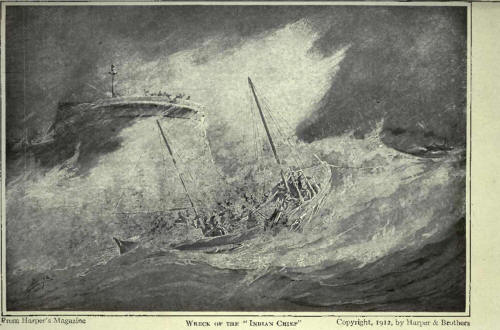

C. N. Cunningham. Ilis wife was a sister of Mrs. Irvine Two of his sons,

Marmaduke and Howard Primrose, met a tragic death by being drowned in

the wreck of the “Indian Chief” on the Goodwin Sands. One daughter,

Elizabeth, was married to Alexander Williamson and lived until her death

in South America. Another daughter, Alice, is now living in Westville.

Mr. Fraser was a most efficient foreman, and some of his ships were of

the finest built in Nova Scotia. He was one of the most highly respected

men in the village and from 1860 till he removed to Pictou, was an elder

in the Tatamagouche Presbyterian congregation.

Henderson and Robert Gass were brothers, sons of John Gass who came from

Dumfries, Scotland, and settled at Pictou in 1816. The former, a saddler

by trade, came to Tatamagouche about 1848 and took up his residence on

the street next to John Millar’s. He was captain of the Lake Road

Company of the Nova Scotia Militia. His wife was Eliza Irish. He died in

the winter of 1912. Among his children are: Mrs. James Ramsey of the

village; Miss Kate Gass, Cambridge; George, of Trenton; and William, of

Sackville.

Robert Gass was a shoe-maker and came to Tatamagouche about the same

time as—perhaps a little later than—his brother. He died n 1894. One

son, Robert, is now living in the United States.

Later on, it may be noted, there came another Robert Gass, who took up

the Blockhouse farm and to distinguish him from his cousin, Robert the

shoe-maker, they were commonly called “Shoe-maker Bob” and “Blockhouse

Bob”. Robert (Blockhouse) Gass was a son of Joseph Gass, who came to

Pictou from Dumfries with his brothers Robert and John in 1816, but who

removed to Cape John in 1842. Robert Gass was twice married to sisters,

Misses Perrin of River John. Several children by his first marriage

still survive. They are: Will, in Bass River; Mrs. Till and Mrs. Elwood,

of Boston; and Mrs. McLellan in the West.

Among others, who in the early “forties” lived on Mech amc Street, we

may note William Higgins, a shoe-maker, and James Grant, a blacksmith.

Both subsequently removed to Wallace.

Until the time of the arrival of these families, nearly all the houses

and places of business at Tatamagouche were on the west side of French

River in the vicinity of Campbell’s shipyards, and there seemed every

indication that the site of the future village would be there. From

Campbell’s to Waugh’s there were houses only at rare intervals and

outside the cluster of buildings at the former place, there was nothing

that could assume even the name of a hamlet. In fact, as late as the

“forties” there were only four buildings between Wm. Campbell’s and

McConnell’s tavern. These were the houses of Neil Ramsey and Mungo

Heughan. the old Presbyterian meeting house and the small shop of John

Blackwood. Alex. Campbell, however, who either owned or controlled

nearly all the land near the French River, was averse to selling, and

men found it difficult, if not impossible, to obtain land from him.

James Campbell and others who owned the lots where the present village

is situated, had no such aversion. They were willing and ready to

dispose of their land. Then the shore along these lots was well suited

for shipyards, as a comparatively deep channel ran close to the bank. It

was for these reasons that the shipbuilders and others who came in the

"forties”, located where they did, and thus, in a great measure,

determined the location of the present village.

A man named Young is said to have been the first to erect a shop in the

present village. He came here interested in shipbuilding, and built a

small store near the site of Thomas Bonyman's forge. This store was

afterwards purchased by Robert Logan and moved down to the corner of

Main Street and New Annan Road where, enlarged and with frequent

repairs, it stands till this day, still in use as a place of business.

One of the first tailors to come to Tatamagouche was Mungo Heughan. He

had been employed aboard a man-of-war and, after leaving the sea,

settled down for the rest of his days at Tatamagouche. He had his shop

and house on the east corner of the present Manse property. For years he

was Superintendent of the village Sunday School; in all probability of

the first regular Sunday School to be held here. John Heughan, who

settled on the New Annan Road, and James Heughan, of Cariboo are two of

his sons.

John McDowl. who came here in 1841 from River John, wras another tailor.

He lived in the house now owned by J. T. B. Henderson, Esq. Previous to

his coming, one Telfer, who came in the eariy “thirties,” and who also

was a tailor, had his shop in this building. John McDowl, the veteran

engine driver is a son.

It was about this time, that Stephen Rood, a ship carpenter, settled in

Tatamagouche. He built and lived in the house now owned by Charles

Brown, Charles Rood, of New Glasgow, is a son.

It was in 1810 that the Rev. Robert Blackwood came to Tatamagouche. He

first lived in a house near where Mrs. Crowe now resides but

subsequently he removed to the house now owned by Charles Brown. His

wife was Anne McCara, daughter of the Rev. John McCara of Scotland. In

their family were Jessie, who was the wife of Rev. Dr. Smith of Upper

Stewiacke; David who lived in Halifax; and William who remained in

Tatamagouche. The last was one of the best known men and merchants in

North Colchester. For a time he was in public life and represented the

Northern District of Colchester in the House of Assembly from 1863 to

1867. In politics he was a strong Liberal and an opponent of

Confederation.

About the same time (1840) David Murdock and his wife, Sara Wilson, both

from Scotland, settled at what has since been known as the Murdock farm,

on Waugh’s River. The property, as we have seen, had previously been

owned by William Currie. Murdock had been a game keeper in the estate of

a Scotch nobieman, and his wife had been the house-keeper. He came out

first and then she joined him. He met her in Truro and conveyed her over

the mountain in a cart. They had no children and the farm was given to

his nephew, David Murdock, father of the present owner John Murdock.

One of the last families that came directly from Scotland to settle at

Tatamagouche, was the Clark family of Aberdeen. It would be sometime

around 1842-3, when two brothers, John and James, who were the first to

come out, arrived at Tatamagouche. They landed at Halifax, and from

there walked to Tatamagouche. Often, in later years, they used to relate

how, on a Sunday morning, when the people were coming from the church,

they reached the village in their bare feet, and had their first meal in

what was to be their future home, at the house of Mungo Heughan.

John settled on the Mill Brook, near what is known as the Peugh Bridge.

At the time of the gold rush to Australia, he, in company with his

brother, went and remained for a number of years in that colony. On his

return he lived for a year on the Hubert Bell farm at Waidegrave, and

then went into business in the village. In 1871, he built the shop now

owned by J. M. Bonyman & Company. In 1860, he was elected elder in the

Tatamagouche Presbyterian congregation, a position which he faithfully

held until his death. For years he was superintendent of the village

Sunday School, to which office he gave his unfaltering attention till

advancing years made it impossible for him to perform its duties. Ilis

venerable figure and kindly word will always be remembered by those who,

as boys and girls, sat on Sundays beneath his charge. In August, 1901,

he met a sudden death, by being drowned while bathing in the river below

his house.

James Clark, on his return from Australia, settled on the farm now owned

by his son, Sydney, at Bayhead. He for number of years was one of the

representatives of Tatamagouche in the Municipal Council. He was also a

Justice of the Peace. He died in 1891.

There were four other members of this family who also settled in

Tatamagouche: George, Charles, Robert, and William. The last three took

up farms on the Mill Brook. George early entered into business for

himself in the village. Beginning in a small way, he built up a

prosperous business and soon became the leading hardware merchant of the

village. So successful was he, that at the time of his death he was the

most influential and probably the wealthiest man in North Colchester. In

politics he was a strong Liberal and a firm believer in the principles

of Free Trade. In 1886, and again in 1890, he was elected to represent

Colchester in tue House of Assembly. He died in May, 1905.

The last settler to come directly from Scotland to Tatamagouche was

David Donaldson, of Perthshire. In 1819, he left Scotland and, after a

voyage of six weeks, landed at Pictou. He first settled at Brule, on the

farm now owned by his grandson. A. P. Semple. He built his first log

house close to the creek which ran through his farm. At the time of his

arrival, this fine property was heavily wooded with hemlock. He appears

to have been particularly successful as a farmer. The land there is very

fertile and it is said that in a few years, He was able, one winter to

sell a ton of flour made from the wheat grown on his own place. After

remaining for seven years at Brule, he removed to French River, near the

bridge now known by his name. At the same time there came to

Tatamagouche with Donaldson, his sons-in-law, Wm. Menzie and James

Semple. The former went first to Fox Harbour, Cumberland County and then

to the “Back Road” to River John. Subsequently he came to the village to

live. James Semple remained on the farm at Brule. Six years later came a

third son-in-law, Thomas Malcolm, who settled at Brule where his son,

Robert D. Malcolm, now resides.

David Donaldson was married to Mary Hutchinson, of Perthshire. He died

in 1891, aged eighty-four, and his ‘wife in 1895, aged ninety-two. Their

sons were Robert, John, and George, who removed to New Zealand and

Australia, and William and David who remained on their father’s farm.

The daughters were Agnes (Mrs. Menzie), Elizabeth (Mrs. Malcolm),

Cecelia (Mrs. Semple), Jane (Mrs. Langille) of the village, and Mary

(Mrs. Wm. Langille), French River The last three are the only surviving

members of the family. Mrs. Menzie, being the eldest, had reached

maturity before leaving Scotland, and was the only member of the family

to speak the Scottish dialect.

Along with shipbuilding came also the sister industry, lumbering. As we

have already noted, the commencement of this industry was the sale of

square pine timber in the Old Country. It was soon eclipsed in

importance by shipbuilding but, nevertheless, it continued to give

employment to many men, particularly in the winter months. At first the

lumber was manufactured entirely by hand, the large logs being sawn into

boards or other material by the laborious efforts of two men on a whip

saw. With the open ng of the English market, and the introduction of

water mills, the industry went forward in leaps and bounds. Small mills,

we have already noted, were constructed by the French, but these were

probably used for grinding grain more than for sawing purposes. William

Waugh, the Bon of old Wellwood Waugh, is said to have been about the

first to build a water mill at Tatamagouche far sawing lumber. Certain

it is that he erected one at a very early date on the small stream which

is still known as the “Mill Brook”. Later on the Hon. Alex. Campbell

built a small mill on the Black Brook, just a little east of where it is

now -crossed by the road to Balfron. The remains of the old dam can yet

be seen. During the "thirties,” a number of others were constructed.

William Campbell built one on the French River on the lot now owned by

James Ramsey. Abram Patterson, of Pictou, also built a small mill on the

Mill Brook branch of the French River. During the subsequent years, a

dozen or so of similar mills were erected at various places on French

and Waugh Rivers and up till the time of the introduction of steam mills

they did all the sawing.

About the early “fifties” Abram Patterson, who was now actively engaged

in the lumbering industry, came to live at Tatamagouche. He bought the

property subsequently owned by his son, the late W. A. Patterson.

Engaged with him in this business was James Primrose of Pictou. For a

time they operated a mill at Porteoues, French River. They then

commenced cutting some of the larger and better lumber on the mountain

lots and erected a mill near Farm Lake. They were the first to commence

here the planing and other manufacturing of lumber.

Aoram Patterson was a son of John Patterson (who came to Pictou in the

“Hector”) and was married to Christina, the eldest daughter of Dr.

MacGregor, the pioneer Presbyterian minister in Pictou. One of his sons,

Archie, as we have noted, was engaged for a number of years in

shipbuilding at Tatmagouche. His youngest son, W. A. Patterson, Esq.,

continued in the lumber business. In 1874 he was elected as a

Conservative to represent Colchester in the Provincial House. He was a

member of that House till 1886, being re-elected in 1878 and 1882. In

1891 he was elected to the Dominion House of Commons and sat in that

House till his retirement from political life in 1896. He died June,

1917.

The year 1847 was a hard one for this community. A financial depression

caused the bottom to fall out of the ship market and, consequently,

there was no profitable sale for ships of any kind. Many of the

shipbuilders of Nova Scotia lost heavily. With scarcely a moment’s

warning, thousands of dollars and the wealth of years were swept away.

It is said that Alexander Campbell was the only timberer on the North

Shore who remained solvent, but this is probably an exaggeration. He,

though he suffered severely, was able to continue his business. This

depression, as the ones of ’25 and '40, soon passed away and times in a

year or so were better than ever.

These years from 1825 to 1847 were crowded with many events and crowned

with much prosperity' for the people of Tatamagouche. Every year, as the

log cabins decreased, the frame dwellings increased. The settlers no

longer struggled for the necessaries of life alone, for into their homes

had already had a few of the simplest luxuries. No longer was it

necessary to carry provisions through the woods from Truro, or along the

shore from Pictou, for a dozen or more merchants were here with their

stores full of various goods and commodities. Labor was abundant and

wages, for those days were good. Tatamagouche was yet to see darker days

by far than those of 1825-47.

One great improvement was in the roads. When the first settlers came

here the only road, or rather trail, was across the mountains to Truro.

If we can rely upon the old French records, this road was then in good

condition, and in all probability its course was followed by the

subsequent settlers. To Pictou there was no path whatever, and as late

as 1793, people went to that place by following along the shore to River

John and from there they would either strike through the woods or

continue along the shore. We have been unable to ascertain when the road

from Pictou to Tatamagouche was opened, but in 1833, we find that the

sum of Ł40 was granted by the Assembly for a bridge at Currie’s

(.Murdock’s). The road must have been opened a considerable time before

this date as, for a number of years, the river was forded at that place.

The first road through the village ran south of the present main road,

somew'here back of where James Ramsey now resides. What is now commonly

known as the “Back Street” is a continuance of the old road.

The first bridge across the French River was built about the same place

as the present one. The next one was placed higher up on the bank and

nearer the main river. It must have been constructed at the early period

before shipbuilding had become of any great importance. The bridge, as

then located, did away with the long and inconvenient Campbell’s and

McCully’s Hills, but its position prevented the launching of any large

ships from Campbell’s yards and consequently it was, when being rebuilt,

moved further up the river to its former site. It was, of course, a

wooden structure. The writer has been unable to ascertain in what year

it was built but, in 1839,4 the sum of Ł1U0 was granted for the erection

of a bridge over the French River and it was, in all probability, during

that year that this bridge was built. At the time of its construction, a

petition was presented to the Government praying that a draw be placed

in the bridge so that those who lived further up the river would not be

precluded from shipbuilding. The petition stated that the river was

navigable one mile above the bridge for ships of twenty feet draught. We

rather fear that the then citizens of Tatamagouche were more eager to

obtain the draw than to sustain their accustomed reputation for

veracity. The present steel structure, which is on the same site, was

built sometime during the “eighties”. The first bridge at Lockerbie’s

was built on the site of the present one, some time about 1840, possibly

a year or so later.

In 1825 people at Tatamagouche had little intercourse with the outside

world. They were a little colony by themselves. In 1847 this was no

longer true. Her ships sailed to every quarter of the globe, and to her

harbour came vessels bearing the Hags of a score of nations and manned

by sailors of various nationalities and speaking a dozen different

tongues. With the exceptions of Halifax, Yarmouth, Sydney, Pictou, and

possibly a few others, Tatamagouche had as much intercourse with the

outside world as any other port in Nova Scotia. Improved reads, too, led

to more communication with nearby places.

In regard to early postal service, we have little information. Wellwood

Waugh was, as we have seen, the first courier between Truro and

Tatamagouche. At that time the only interprovmcial mail coming from what

is now the Upper Provinces, was landed at Tatamagouche. The sailing

vessel “Mercury” made regular trips to and from Quebec. It was evidently

this mail which Waugh carried as far as Truro. Who succeeded him in this

responsible duty is unknown, After a time this method of bringing the

mails from Quebec was abandoned, and apparently they were brought all

the way by land for, we find that in 1821, the inhabitants of Pugwash,

Wallace, and Tatamagouche presented a petition to the House of Assembly

for a sum to be set aside to defray the expense of a weekly mail service

to those places from the main post road that ran over the mountains in

the vicinity of Westchester. There is no record to show that the prayer

of this petition was ever granted, and we have never heard of any mail

route running through those places to Tatamagouche.

About 1843, a tri-weekly mail was established between Halifax, Pictou

and various points along the northern shore of Nova Scotia. A man by the

name of Arnison drove this mail from Pictou to Tatamagouche. Many can

yet recollect him as, driving into the village over Lockerbie’s Hill, he

would announce his coming by the blowing of a horn. Subsequently, James

Ulair, who came to Tatamagouche about the middle “fifties”, drove the

mail from Pictou to Tatamagouche, In Belcher’s Almanac this mail,

running to Pictou, Wallace and Amherst, is said to have run tri-weekly,

but those whose memory reaches back into those years say that at that

time the mail came through Tatamagouche but once a week There was also a

mail from Truro which at first came at irregular intervals, usually

brought by a man or boy on horseback One of the last drivers was Tim

Archibald, who drove two horses tandem.

During the “sixties”, when the “Heather Bell” was plying between Brule

and Charlottetown, mails were received here twice a week from both

Halifax and the Island.

In 1867, “Blair’s Express”, owned by James Blair, ran over the mountain

to Truro. We take the following from Belcher’s Almanac of that date:

“Blair's Express, a taal waggon, leaves Truro tor Tatamagouche, Waliaee

and Pugwabli on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, returning on the

intervening days.”

With the opening of the railway to Pictou and the main line through

Wentworth, we received regular mails from those places.

As far as we are aware, the first postmaster at Tatamagouche was Wm.

McConnell, who, as we have seen, conducted a tavern where the "Stirling

Hotel" is now situated. The writer has seen a letter bearing date 1843

addressed “c/o Wm. McConnell, postmaster”. About 1855, possibly before,

John Lombaid was appointed postmaster. Four years later the office was

moved up the road and kept by James McLearn In 1863, Wm. Fraser* became

postmaster and, in 1866, Isaac Blair was appointed. Three years later,

Robert Purves became postmaster, and held the position till his death

when he was succeeded by his widow. At her death, in 1904, Dr. Johnson

was appointed.

The years following the depression of 1847 were busy ones for the

shipbuilders at Tatamagouche. The English market was good and there

arose a demand in Newfoundland for vessels of about 100 tons built

especially for seal fishing. Several who had not previously gone into

the business began at once building vessels of this type. The year 1857

was long known, indeed to this day, as the "big year” at Tatamagouche.

In that year fourteen vessels were on the stocks at one time. Campbells,

Purves, Logan, Kent, Patterson, Reilly, Robert Bryden, Wm. Blackwood,

and B. F. McKay all built that year. Some had two or three. The whole

shore from Lockerbie’s to Ross’ Point was one busy hive of industry. One

vessel was built on the shore across from Campbell’s Point, another one

on Ross’ Point, two or three at Campbells’, one at the mouth of the

small creek which runs through Cordon Clark's field, three or four in

the yards of Kent, Logan and Patterson, and two up below James Bryden’s,

where Reilly and McLaren were building. This was the high water mark for

shipbuilding at Tatamagouche. For a few years markets continued good and

all went well. But every few years there came a repetition of the

financial crises which we have already noted and then the entrance of

steamers into the work of ocean transportation was gradually ruining the

market for wooden sailing vessels.

On the first day of April, 1854, there occurred an unusually heavy

freshet. The exceptionally heavy snow-fall of the winter had all

remained on the ground until the beginning of a heavy rainstorm which

commenced on one of the last days of March. Many of the bridges on

Waugh’s and French Rivers were swept away, and a large jam of ice formed

fiom Patterson’s wharf across to Steele’s Island. The waters, in rising,

engulfed the island and flooded the barn of John Steele which was built

on the low slope of the mainland near the island. All his cattle were

drowned. The following account of the storm is taken from the diary of

the Rev. Robert Blackwood:

“A most tearful storm and freshet on the first, of April, 1854. It

melted the snow, raised the ice, and carried before it bridges to an

claiming extent on Waugh’s River. Campbell’s, Murdock’s and Lockerbie’s

bridges were carried away with one general sweep. The river must, with

'he ice, have raised eight or ten feet. One poor man, Steele, lost

thirty head of sheep, twelve head of cattle, one horse, and his

buildings, to which the freshet never rose before.”

One who, during the “fifties”, entered into business at Tatamagouche,

and who was the first to erect a shop of two stories in the viiiage, Was

Stewart Kislepaugh. His was such a peculiar character that we must give

him more than passing notice. His father had been a French soldier who

during the retreat from Moscow had served under Napoleon. After the war,

the old soldier came to Nova Scotia and finally settled on Tatamagouche

Mountain. There, one of his neighbours was a man who, during the same

wars had fought under the banner of England, and the old warriors rather

than forget their quarrels of the past, showed a disposition to fight

them over once again. Stewart, as a young man, came to work in the

village, first as a clerk for Robert Purves and then for James Campbell,

who ran a small store near where J. R. Ferguson now resides. Eventually

he commenced business for himself His shop was destroyed by fire.

Stewart had just opened a cask of turpentine and some of the contents

had been spilled on the floor, A number of men were in the store at the

time, and one of them who was smoking remarked “Stewart, you don't know

the great risk you are running with that turpentine.” He was alluding to

the danger of the. At the same time a lighted match fell from his hands,

and, before the men could think or act, the interior of the building

burst into flames. He rebuilt, this time a building of two stories,

where the store of James Bonyman & Co. now stands. In 1862 this shop was

also destroyed by fire. Stewart was left a poor man and, for a number of

years was absent in South America. Returning, he found himself in

poverty. Gone was all his former prosperity and, like King Lear, he was

content to live in a mere hovel. He was a man of much intelligence, was

well read and possessed a great deal of public spirit. Perhaps more than

anything else he was noted for his ready wit and practical jokes. Many

of his sayings and stories are still remembered and retold, always with

appreciation. During his last years he lived in an old shop across the

road from where D. W. Menzie now resides. A great part of his time he

used in doing acts of kindness to those whom he could in any way assist.

There are many today who regard his memory with the warmest feelings,

and think with sadness that a personality which had so much of the

finest qualities accomplished so little. “Stewart’s” pump, which, due

mainly to his labours, was preserved for the public, stands as his

monument, and daily recalls the memory of this peculiar but zealous

citizen. He died in the winter of 1894.

About 1850, James Blair came from North River to take over the hotel at

Tatamagouche. He also ran the stage from Truro to Tatamagouche and

Wallace. His wife was a Miss Lyons. Isaac Blair is his son.

In 1854, William McKenzie came, as a young man, from Pictou to act as a

foreman in the shipyard of Archibald Patterson. He was a man strong in

body and in mind, and in every way typical of the splendid, "virile

people which at that time Nova Scotia and Pictou County in particular,

seemed able to produce. As a ship foreman he had few equals, being at

all times able to hold the confidence of his men and employers; and it

has often been sail that he was able to get more work out of his men

than any other foreman of his time. In later days, when he retired from

active work., his advice was readily sought after m matters relating to

the construction of wooden ships. He died in the winter of 1911, aged

eighty-seven.

The first carriage builder to come to Tatamagouche was John A. McCurdy,

of Onslow. In the early “fifties”, he commenced business in a shop about

opposite the present Post Office. He was married to Elizabeth Bryden and

lived in the house now owned by Dr. Sedgwick. His two children are Mrs.

C. N. Cunningham of the village, and Gordon, who is Police Inspector of

the Rainy River District. About 1860, McCurdy moved back to Onslow and

Alex. McLeod commenced the same business in the shop now owned by James

Perrin.

In 1854, James McLearn came from Halifax to Tatamagouche. He built the

house now owned by Mrs. Menzie. He engaged in shipbuilding and built a

number of vessels in the yards below where James Bryden now resides. He

also bad charge of the first telegraph office to be established in the

village. His wife was a sister of Charles Reilly. He removed, first to

California, then to Halifax, where he died.

Those who, during the subsequent years, have come to live at

Tatamagouche are so well known to the public of today that to deal with

them individually would be superfluous. Some are still with us; others

have but recently passed away. Of those who, during or about the years

1855-65, came to Tatamagouche from various places in Pictou County, we

may mention: Daniel Barclay, Alexander Matheson, and David Eraser,