|

United Empire Loyalists.—List

of Scottish names appearing in Lord Dorchester's list. — A "Distinguished

Individual's" opinion of the Highlanders of that Generation.—Mr. Croil's

description of the situation and condition of the Loyalist Settlers in the

United Counties.

A reference to the "Old U. E.

List," compiled by Government by direction of Lord Dorchester, shows the

original United Empire Loyalists in the Province. In many instances,

however, instead of the Township being given, it is merely stated that lands

were allotted in the Eastern District. My only plan will, therefore, be to

insert in the appendix the names of all who appear to have settled in that

district, showing the respective Townships when given, and omitting those

who are stated to have settled in Townships outside Glengarry.

This list was prepared in

pursuance of the Order-in-Council of 9th November, 1789, wherein it was

stated that it was His Excellency's desire "to put a Marke of Honour upon

the families who had adhered to the unity of the Empire and joined the Royal

Standard in America before the Treaty of Separation in the year 1783 * * to

the end that their posterity may be discriminated from future settlers * *

as proper objects by their presevering in the Fidelity and Conduct so

honourable to their ancestors for distinguished Benefits and Privileges."

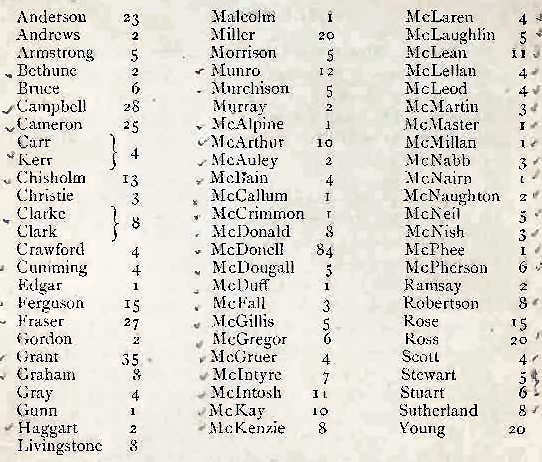

The list is preserved on

record in the Crown Lands Department, and it shows that those of the name of

the Clan which gave its name to Glengarry outranked in number those of any

other individual name in the Province, and that there were more Loyalists of

that name than any three English names combined in the whole Province. But

though there were more Macdonells from Glengarry in Scotland than any

others, there were, as previously stated, representatives of almost every

Highland Clan and every Scottish name. A list of the names will prove it,

and as the statement has been made by one who professes to speak

authoritatively on the subject, and to know whereof he

speaks, and writes that ''the Scotch and Irish element; in the United Empire

Loyalists is too small as compared with the preponderating English and

German to be taken into account," I give it, with the number of each name

I quote from the original

list. Names were subsequently added, from time to time, by Order in Council,

on the special application of those who had omitted to take the precaution

in the first instance. The additions would not alter the proportion of the

above nomenclature. I am satisfied, however, from facts within my knowledge,

that many of the Highlanders never took the trouble of having their names

inserted at all, first or last. Thus Bishop Macdonell (who came to Canada

over twenty years after the Loyalists had settled here) writing

subsequently, states, "I had not been long in the Province when I found that

few or none of even those of you who were longest settled in the country

had. legal tenures of your properties. Aware that if trouble or confusion

took place in the Province your properties would become uncertain and

precarious, and under this impression I proceeded to the seat of Government,

where; after some months hard and unremitting labour, through the public

offices, I procured for the inhabitants of Glengarry and Stormont patent

deeds for one hundred and twenty-six thousand acres of land." When they

would not trouble about taking out their patents, many of them would not

think of having their names inserted on the roll.

The above list is, I submit,

a fair representation of those who to-day comprise what the author of the

essay referred to, Mr. George Sandfield Macdonald, B.A., of Cornwall, is

pleased to designate as the "Keltic" population of the Province of Ontario.

For further information on the subject and a comparison of the number of the

''Kelts" with the English and Germans amongst the Loyalist settlers of the

Eastern District I refer him to Lord Dorchester's list, simply stating that

of the three English names most frequently met with Smith, Jones and Brown,

there were, all told, just eighty, or four less than of one Highland Clan,

while of the Germans, taking as a criterion all the names to which the

prefix "Van " is attached, from Van Allen to Van Vorst. there were but

forty-two, exactly half of the number of those from whom the County of

Glengarry took its name.

The statement to which I have

referred, however, is not the only one in this singular essay, which was

read before the Celtic Society of Montreal, which requires explanation and

correction. We are gravely informed that the "Keltic" settlers in Canada of

the period spoken of (the early settlement of Glengarry, 1783-6 had no

mental qualifications to entitle them to take rank with the founders of the

American plantations, that unlike the Puritans of New England, the Catholics

of Maryland, the Cavaliers of Virginia, the Huguenots of South Carolina and

the followers of William Penn, the compelling force leading to change of

country was in contrast to the -motives of a higher order, as in those

cases, that long subjection to the despotism of chiefs and landlords had

numbed the finer qualities and instincts, and that even the physique had

degenerated under oppression. We are told, too, that an analysis is required

of the generations which have succeeded the original settlers, psychological

and sociological no less, to grasp the full significance of the lives and

actions of those he is pleased to consider "distinguished individuals," and

the "people" among whom they deigned to move, which was a very gracious

condescension on the part of these distinguished individuals, seeing that

the experience and ideas of the 'people' were confined within the smoke of

their own bush fires. Now, all this may be very fine writing, and display a

large amount of culture in one doubtless a typical specimen of the modern

distinguished individuals referred to, but it is very grievous rubbish

nevertheless, and a most uncalled for and gross calumny on the men who left

Scotland and settling in Canada, after fighting through the War, were

largely instrumental, not only in preserving it by their prowess, but

developing it from the primeval forest to the fruitful land it is to-day.

Their descendants will neither credit nor relish the unworthy sneers at the

stunted limbs and intellects and ignoble motives of those to whom they have

every reason to look back with pride, and who laid the foundations of the

homes and Institutions we now enjoy.

This, however, is a

digression. The facts are there to speak for themselves, and are themselves

a refutation of the theories and allegations of the essayist—as well might

he tell us that the men of the same generation who entered the Highland

Regiments, and to whom Pitt referred, were feeble and stunted of limb, with

their finer qualities numbed and their instincts dwarfed by years of

oppression and tyranny of "so-called chieftains."

Glengarry, where they

settled, is the most easterly County of what is now the Province of Ontario,

"the upper country of Canada," to the south being the River St. Lawrence, on

the east the Counties of Soulanges and Vaudreuil in the Province of Quebec,

to the north the County of Prescott, and the west that of Stormont.

Alexandria, which may be considered the centre of the County, is about

mid-way between the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers, and is about equi-distant

from the political and commercial capitals of the Dominion or to be precise,

fifty-six miles from Ottawa and fifty-four from Montreal. The United Empire

Loyalists of course settled largely in the front of the County, along the

banks of the River St. Lawrence, the later emigrants locating themselves in

rear of the preceding ones to the north.

Mr. Croil, in his "Sketch of

Canadian History," gives an admirable description of the situation and

condition of the United Empire Loyalist soldier-settler in the adjacent

County of Dundas, equally applicable, of course, to his late comrade in arms

in Glengarry. The circumstances of the officers and their families were

necessarily somewhat better, as having the pensions of their respective

ranks at the date of the reduction of the various corps, they could rely

upon a supply of ready money at certain stated 'ntervals, and though the

amount was comparatively small, yet money went far u those primitive days,

and their families had but few opportunities of indulging any extravagant

tastes they might have acquired from their former circumstances of life.

Owing to the number of officers whoa settled in the Eastern District of the

Province they formed among themselves a society quite equal to that of any

portion of the Province, while their birth and education enabled them to

hold their own with the official circles at York or among the largely

mercantile aristocracy of Montreal when occasion arose for them to visit

either of those places. Such was their number that a Board of Officers,

composed of Colonel John Macdonell (Aberchalder), of Glengarry, Captain John

Macdonell (Scotus), of Cornwall, and the Reverend John Stuart (formerly

Chaplain Second Battalion, King's Royal Regiment of New York), of Kingston,

was required to administer the necessary oaths to enable them to draw their

pensions from time to time.

Mr. Croil states the

Proclamation of Peace between Great Britain and the United States of America

witnessed at least a partial fulfilment of the prophecy that men shall beat

their swords into plough-shares and their spears into pruning hooks. The

brave and loyal subjects, who during the fierce struggle which then

culminated had remained faithful to the British Crown, being no longer

required to fight their country's battles, were now destined in a very

different way to add to their country's greatness. It was determined that

liberal grants of land should be freely given to the disbanded soldiers.

This was simply characteristic of that principle of high honour and justice

which, in every period of its history, has distinguished the British

Government. The properties of all who had withstood the Republican

Government in the States were of course confiscated, and peace being

proclaimed, not only was the soldier's occupation gone, but his farm and all

his earthly possessions were-forfeited for ever.

Having arrived at Cornwall,

or ""New Johnstown " as it was then called, in compliment to Sir John and

the capital of their former settlement in the fertile Mohawk Valley, the

soldiers found the Government Land Agent, and forthwith proceeded to draw by

lottery the lands that had been granted to them. The townships in which the

different corps weir io settle being first arranged, the lots were numbered

on small slips of paper, and placed m a hat, when each soldier in turn drew

h>s own. As there was no opportunity for examining the comparative quality

of the lands, so there was little choice in the matter ; but by exercising a

spirit of mutual accommodation, it frequently resulted, that old comrades

who had stood side by side in the ranks, now sat down side by side, on the

banks of the St Lawrence.

With what feelings of intense

interest, mingled even with awe and melancholy, must these settlers have

regarded this introduction to their new wilderness home ! How impatient each

to view the particular spot where his lot had been cast ! Everywhere save in

the neighbourhood of the Longue Sault Rapids the landscape wore an aspect of

wild and gloomy solitude : its solemn stillness interrupted only by the deep

murmuring of the mighty river as it rolled along its flood to the ocean. On

leaving the river, the native grandeur of the woods, tenanted only by the

Indian hunter and his scarce more savage prey, must have filled them with

amazement. Well might they exclaim, is this our inheritance, our future home

! Are these to be at once our enemies and our associates ! Can it be that

these giant denizens of the forest are to succumb to our prowess, and that

this vast wilderness is to be converted into fruitful fields!

The first operation of the

new settler was to erect a shanty. Each, with his axe on his shoulder,

turned out to help the other, and in a short time every one in the little

colony was provided with a snug log cabin. All were evidently planned by the

same architect, differing only in size, which was regulated by the

requirements of the family, the largest not exceeding twenty feet by fifteen

feet inside, and of one storey in height. They were built somewhat similar

to the modem back-woodman's shanty. Round logs, roughly notched together at

the corner, and piled one above another, to the height of seven or eight

feet, constituted the walls. Openings for a door, and one small window,

designed for four lights of glass seven by nine were cut out—the spaces

between the logs were chinked with small splinters, and carefully plastered

outside and inside, with clay for mortar. Smooth straight poles were laid

lengthways of the building, on the walls, to serve as supports for the roof.

This was composed of stripes of elm bark, four feet in length, by two or

three feet in width, in layers, overlapping each other, and fastened to the

poles by withs. With a sufficient slope to the back, this formed a roof

which was proof against wind and weather. An ample hearth, made of flat

stones, was then laid out, and a fire back of field stone or small boulders,

rudely built, was carried up as high as the walls. Above this the chimney

was formed of round poles notched together, and plastered with mud. The

floor was of the same materials as the walls, only that the logs were split

in two, and flattened so as to make a tolerably even surface. As no boards

were to be had to make a door until they could be sawn out by the whip saw,

a blanket suspended from the inside for some time took its place. By and by,

four little panes of glass were stuck into a rough sash, and then the shanty

was complete; strangely contrasting with the convenient appliances and

comforts of later days. The total absence of furniture of any kind whatever,

was not to be named as an inconvenience by those who had lately passed

through the severest of hardships. Stern necessity, the mother of invention,

soon brought into play the ingenuity of the old soldier, who, in his own

rough and ready way, knocked together such tables and benches as were

necessary for household use.

As the sons and daughters of

the U. E.'s became of age, each repaired to Cornwall, and presented a

petition to the Court of Quarter Sessions, setting forth their rights; when,

having properly identified themselves, and complied with the necessary

forms, the Crown Agent was authorized to grant each of them a deed for two

hundred acres of land, the expenses incurred not exceeding in all two

dollars. In addition to the land spoken of, the settlers were otherwise

provided by Government with everything that their situation rendered

necessary—food and clothes for three years, or until they were able to

provide these for themselves; besides, seed to sow on their new clearances,

and such implements of husbandry as were required. Each received an axe, a

hoe and a spade; a plough and one cow were allotted to two families; a whip

and cross cut-saw to every fourth family, and even boats were provided for

their use, and placed at convenient points of the river. They were of little

use to them for a time, as the first year they had no grists to take to

mill.

But that nothing might seem

to be awanting, on the part of Government, even portable corn mills,

consisting of steel plates, turned by hand like a coffee mill, were

distributed amongst the settlers. The operation of grinding in this way, was

of necessity very slow; it came besides to be considered a menial and

degrading employment, and, as the men were all occupied out of doors, it

usually fell to the lot of the women, reminding us forcibly of the Hebrew

women of old, similarly occupied, of whom we have the touching allusion in

Holy Writ, ''Two women shall be grinding at the mill, the one shall be taken

and the other left."

In most cases, the settlers

repaired to Cornwall each spring and fall, or during the winter, and dragged

up on the ice, by the edge of the river, as much as he could draw on a hand

sled. Pork was then, as now are staple article of animal food; and it was

usual for the settlers, as soon as they had received their rations to smoke

their bacon, and then hang it up to dry; sometimes it was thus left

incautiously suspended outside all night: the result not unfrequertly was

that, while the family was asleep, the quarter's store of pork would be

unceremoniously carried off by the wolves, then very numerous and

troublesome, and in no wise afraid of approaching the shanty of the newly

arrived settler. Frequently too, during the night, would they be awakened by

these marauders, or by the discordant sounds of j pigs and poultry

clustering round the door to escape from their fangs.

There was in former times a

deal of valuable timber standing in the Counties. Huge pine trees were cut

for ship's masts, measuring from ninety to one hundred and twenty feet in

length, and from forty to forty-eight inches in diameter, when dressed for

market. One such piece of timber must have weighed from twenty or

twenty-five tons. These mast tress were dragged from the wood by from twelve

to sixteen pairs of horses. A single tree was sold in Quebec as a bow-sprit

for $200. Of white oak, averaging when dressed from forty five to sixty-five

cubic feet, and of the best Canadian quality, there was abundance; this

found a ready market at from 2s. 6d. to 3s. per foot. Iinferior quality of

this timber was converted into stave blocks, and also shipped to Quebec. At

a later period, large quantities of elm and ash were sent to market from

this County, while beech and maple, then considered worthless, were piled up

in log heaps and burned, the ashes being carefully gathered and sold to the

merchants, to be made into potash.

There being ample employment

on the father's farm, yet uncleared, for all his sons, there was little

inducement for them to think of setting up for themselves; as a consequence,

the lands the children had drawn were of little value to them in the

meantime. U. E. rights became a staple article of commerce, and were readily

bought up by speculators, almost as fast as they came into the hands of the

rising generation. A portion of what remained to the farmer or his family

was soon sold in payment of taxes, at sheriff's sales, and these lots, too,

usually fell into the hands of land jobbers. Many of the lots had never been

seen by the parties who drew them, and their comparative value was

determined either by their distance from the river, or the pressing

necessity of the party holding them. It thus happened that lands in the rear

townships, which in a very few years brought from twenty to thirty dollars

per acre, were then considered worthless ; and lots even more favourably

situated, in respect to locality, were sold, if not for an old song, at

least for a new dress, worth perhaps from three to four dollars in cash. We

have even been told credibly that two hundred acres of land, upon which now

stands a flourishing village in the adjoining County of Dundas, was, in

these early days, actually sold for a gallon of rum. The usual price of fair

lots was from $25 to $30, some even as high as $50 per 200 acres. At $30 the

price would be fifteen cents per acre. The same lands were even then resold

to settlers, as they gradually caine i.i from Britain and the United States,

at a price of from $2 to $4 per acre, thus yielding a clear profit to the

speculator of 1000 per cent, on his investment, a profit in comparison with

which, the exorbitant interest of later days sinks into utter

insignificance.

The summer months were

occupied by the early settlers in burning up the huge logs that had

previously been piled together, and in the sooty and laborious work of

reconstructing their charred and smouldering remains into fresh heaps; the

surface was than raked clear of chips and other fragments, and in the autumn

the wheat was hoed in by hand. During winter every man was in the woods,

making timber, or felling the trees to make way for another fallow. The

winters were then long, cold and steady, and the fall wheat seldom saw the

light of day till the end of April-' the weather then setting in warm, the

dormant breaks of wheat early assumed a healthy an^ luxuriant vegetation.

Thistles and burdocks, the natural result of slovenly farming, were unknown,

and neither fly nor rust, in these good old days, were there to blight the

hopes of the primitive farmer. The virgin sold yielded abundantly her

increase ; ere long there was plenty in the land for man and beast, and,

with food and raiment the settler was contented and prosperous.

There was in the character of

the early settlers that which commanded the admiration and respect of all

who were brought into contact with them. Naturally of a hardy and robust

constitution, they were appalled neither by danger nor difficulties, but

manfully looked them fair in the face, and surmounted them all. Amiable in

their manners, they were frugal, simple and regular in their habits. They

were scrupulously honest in their dealings, affectionate in all their social

relations, hospitable to strangers, and faithful in the discharge of duty.

While we say this much of the

early settler, let us not be understood as wishing to hold them up as

paragons of perfection—as examples iri all things to their descendants. They

had their failings, as well as their virtues, but we must make allowances

for the circumstances in which they were placed. They were charged by the

early missionaries, and perhaps with some degree of truth, "as wofully

addicted to carousing and dancing," but these were the common and allowed

amusements of the times in which they lived It may, however, be said with

truth, that forms of licetiousness and profligacy, which are not uncommon in

the present day, would have aroused the indignation of the early settler,

and met with reprobation, if not chastisement at their hands. It is true,

they were not of those who made broad their phylacteries, or were of a sad

countenance, disfiguring their faces, and for a pretence made long prayers.

Innured to a life of hardship and toil,—without the check of a Gospel

ministry, and exposed to the blunting influence of the camp, the barrack and

the guard room, we must be content to find them but rough examples of

Christian life. The scrupulous and uistrustful vigilance, however, with

which modern professors of every creed eye their fellow men, and require

every pecuniary engagement, no matter how trivial, to be recorded in a

solemn written obligation, stands out in striking contrast to the practice

of the early settlers, among whom all such written agreements were unknown,

every man's word being accounted as good as his bond. Lands were conveyed

and payments promised by word of mouth, and verbal agreements were held as

sacred as the most binding of modem instruments.

In course of a few years the

settlers were enabled to supply themselves with the necessaries of life from

the mid and the store, and the roving and dissipated life of the soldier was

forgotten, in the staid and sober habits of the hard working farmer. A few

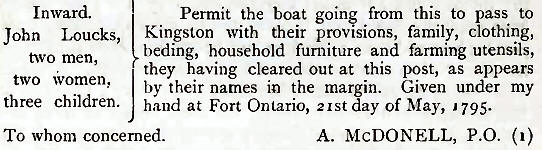

of a more adventurous turn of mind at times would man a boat, and, ascending

the river to Oswego, take a circuitous route by lakes and rivers, betimes

carrying their boats shoulder high for miles at a stretch, and finally reach

the green valley of the Mohawk, dear to them still in memory. Returning,

they brought such articles of merchandize with them as they could transport,

and, providing themselves with a passport at Carleton Island, they swiftly

glided down the river. The following is a copy of such a passport:—

Having sufficiently

trespassed on Mr. Croil's pages, 1 shall now quote from those of Judge

Pringle.(2) The latter is himself a descendant of a United Empire Loyalist

family, and has certainly done much towards collecting such records relating

to them as are at this late date accessible :

It is unfortunate that no

effort was made in the early days of the settlement to preserve records of

the services, the labours and the sufferings of the U. E. Loyalists both

before and after their coming to Canada.

One can easily understand why

such records are so few. For many years after 1784 there were but few who

were able to keep a diary, and they, in common with the rest of the

settlers, were too busy, too much engaged in the stern work of subduing the

forest and making new homes, to have much time for anything but the struggle

for existence.

Each U. E. Loyalist had some

story to tell of the stirring times through which he had passed. Some of the

older men could speak of service in the French war, under Howe, Abercrombie,

Wolfe, Amherst or Johnson; perhaps of the defeat of Braddock, or of the

desperate fight at the outworks of Ticonderoga, where Montcalm drove back

Abercrombie's troops; of success at Frontenac or Niagara; of scaling the

Heights at Quebec, and of victory with Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham; of

the long and perilous voyage down the St. Lawrence with Amherst, and of the

capitulation of Montreal. There were but few who could not tell of

adventures in the Seven Years' War from 1776 to 1783, and of loss of home,

property and friends, for the part they took in it; while many could speak

from personal experience of cruel wrong and persecution suffered by them as

a punishment for their loyalty. No doubt when neighbours met together on a

winter evening to chat beside the great fireplace tilled with blazing logs,

many an hour was passed in the telling of tales of the troubles and

adventures they had encountered. These stories have gradually faded and

become dim in the recollection of the people; here and there a few facts can

be got from some family that has cherished the remembrance of them as an

heirloom. A Fraser could tell of the imprisonment and death of a father; a

Chisholm of imprisonment, and escape through the good offices of a brother

Highlander in the French service; a Dingwall of the escape of a party

through the woods, of sufferings from cold and hunger, of killing for food

the faithfal dog (1) that followed them, and dividing the carcase into

scanty morsels; a Ferguson of running the gauntlet, imprisonment, sentence

of death, and escape; an Anderson of service under Amherst, of the offer

first of a company, then of a battalion, in the Continental Army, as the

price of treason, of being imprisoned and sentenced to death, and of escape

with his fellow-prisoner to Canada.

It is probable that not a few

of the Highlanders could tell of service on one side or the other in the

abortive rising under "Bonnie Prince Charlie" in 1745, which, after

successful actions at Preston Pans and Falkirk, was quenched in blood on

Culloden Muir in 1746. Some, like John McDonell (Scotus), might be able to

show a claymore with blade dented by blows on the bayonets of Cumberland's

Grenadiers. |