|

Frederick Maby was a

native of Massachusetts. He appears to have not taken a very active part

throughout the whole of the Revolutionary War, yet there is undeniable

evidence that he had joined the Royal standard previous to 1783, for it

is so mentioned in the official list of United Empire Loyalists

preserved in the Crown Landsí department of the Ontario Government.

Massachusetts surpassed

all other states in the stringency of the laws against the Loyalists

{Vide supra Chap. V.) Immediately after the Treaty of Paris, the power

of the triumphant insurgents being secured, the hatred of the new

government for those that remained loyal showed itself unmistakably.

Sure of immunity the Americans treated the families of the Loyalists

with the utmost severity. Frederick Maby owned a large farm in

Massachusetts and was accounted a wealthy man for those times, for he

was rich in flocks and herds. But night after night the grossest

outrages were inflicted on the unoffending animals of this Loyalist

owner. One night sixteen of his cows had their tails cut off. During

another the sinews and tendons of the hind legs of his horses were cut

and the poor animals had to be shot. Ears were slit, nostrils split

open, and other most dastardly outrages inflicted without the

condemnation of the Legislature. Nothing remained but voluntary exile to

Canada.

Accordingly, in 1785,

the Maby family fled to New Brunswick, settling at St. John along with a

cousin, named Peter Secord. At their home in that province they were

occasionally visited by an English trapper, Ramsay by name, and, as it

was in the tale of one of his adventures the Mabys first heard of the

Long Point district, it may be worth while to relate it.

This trapper was

accustomed to make yearly visits up the lakes for the purpose of trading

with the Indians. On one of these trips he. took his little nephew with

him, a boy at that time about 10 years of age. During his voyage along

the northern shore of Lake Erie with his canoe richly laden with gaudy

prints, and the trinkets so dear to the hearts of the dusky natives, and

also with a considerable quantity of liquor, he came to Long Point and

landed for the night. There they fell in with nine Indians, whose eagle

eyes took an inventory of the contents of the canoe, and in one of those

treacherous outbursts of overwhelming covetousness, seized his boat and

merchandise. It was not long before they got drunk on his fire-water and

resolved to burn him at the stake and hold a war dance round the flaming

body of the unfortunate white man. However, the potent liquor proved

rather too much for the Indians, and when they found themselves able to

stand on their feet only with difficulty, they resolved to leave the

prisoner alive till morning. So they bound the Englishman, his back to a

tree and his hands tied around it by thongs of buckskin, and in the most

blissful unconsciousness of what was in store for them, eight lay down

to sleep, leaving one of their number as guard. This one relieved his

loneliness by copious draughts from the bountiful supply of good liquor

so fortunately provided.

Unfortunately for them,

they had neglected to tie the boy, who was hiding timidly among the

trees on the outskirts of the camp. Ramsay watched his chance, and

calling the boy, asked him to steal a knife and cut the thongs which

bound his hands. The boy did so, and forthwith Ramsay seized the knife,

and making a dash at the already tottering guard, struck him to the

heart. Then seizing a musket he proceeded to brain the whole party, an

easy task, for the Indians had long since passed the stage of

consciousness. The tables being thus successfully turned the Englishman

and his nephew reloaded their canoe and proceeded on their journey.

This tragic tale,

whether it is to be credited or not, is at least believed by the

descendants of the Maby family now living, who say that it has been

handed down from generation to generation in their family as a true

adventure of their friend, in the locality where their family afterwards

settled.

Let us come back,

however, to something which may well be regarded as more authentic by

the sceptical minds of this sceptical age.

On one of his

subsequent trips up the great lakes, Ramsay was accompanied by Peter

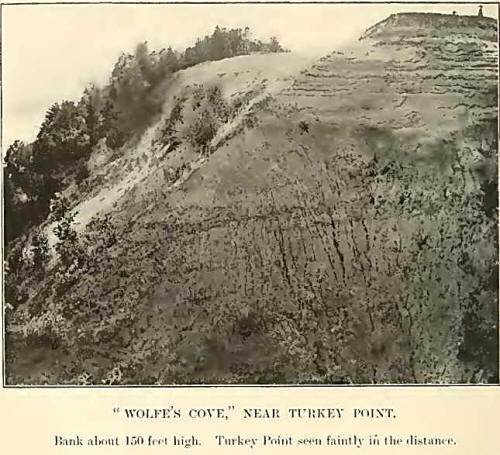

Secord. Together they visited Turkey Point and explored the country

inland for some distance. Secord was very much delighted with the land,

and on returning to New Brunswick persuaded his cousins to move west.

The long journey was accomplished in 1793, and they settled in the

township of Charlotteville, on the high land overlooking Turkey Point.

Mr. Maby, however, died

within a year of his coming to his new home, and was buried on the top

of the high ridge which skirts the lake. In 1795, when

Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe visited the Long Point district he was shown

this grave, the grave of the first white man who had died in the

district, and tfre Governor knelt with reverence by the rudely-shaped

mound.

The wife of Frederick

Maby was named Lavinia. In 1796 she applied for a further grant of land

in her own name. On the 20th of June of the year mentioned, a list of

applicants for lands in the townships of Walsingham, Charlotteville,

Woodhouse, and Long Point settlement generally, was filed in the office

of acting Surveyor-General Smith. The names of some of the applicants

are well known, Ryerse, Maby, Backhouse, Secord and others. In the case

of Mrs. Maby, a widow, about whose patent there was some delay in the

department, Governor Simcoe was very peremptory in his order that she,

being the widow of a Loyalist, must have her application promptly

attended to.

The family of Maby are

connected with the Teeple, Stone, Secord, Smith, Layman and Montross

families. Their descendants live at present in Charlotteville and

Walsingham. |