|

Modern Territorial

Divisions of York.—Parliamentary Representation. The Rebellion.—Want of

Harmony Among, its Leaders. —Inaction and Defeat.—Execution of Samuel

Lount and Peter Matthews.—The Place of their Interment.—Gallows Hill.—

Origin of the Name.

IN addition to the

statutory territorial divisions indicated in the preceding chapter,

several Acts of partial application only, affecting the County of York,

were passed both before and after the Union of the Provinces of Upper

and Lower Canada in 1841. In 1827, 1832 and 1836, three several

enactments came into operation regulating or affecting the local

boundaries, but in a brief sketch like the present it would serve no

useful purpose to follow minutely the course of Provincial legislation.

Suffice it to say that by the statute 14 and 15 Victoria, chapter 5,

passed during the session of 1851, just before the second Lafontaine-Paldwin

Administration went out of office, it was enacted that the County of

York should consist of the townships of Etobicoke, Vaughan, Markham,

Scarborough, York, King, Whitchurch, Gwillimbury East and Gwillimbury

North. By-4his Act, which came into operation on the 1st of January,

1852, the counties of York, Ontario and Peel were declared to be united

for municipal and judicial purposes. By section 5 provision was made for

the dissolution of unions of counties, and under this enactment Ontario

separated from York and Peel at the close of the year 1853. York and

Peel remained united until 1866, when a separation took place, and they

have ever since been entirely disti ict municipalities.

Several subsequent

partial enactments were consolidated in chapter 5 of the Revised

Statutes of Ontario, the 41st section whereof enacts that the County of

York shall consist of the townships of Etobicoke, Georgina, Gwilhmbury

East, Gwilhmbury North. King, Markham, Scarborough, Vaughan, Whitchurch,

York, the City of Toronto, and the villages of Aurora, Holland Landing,

Markham, Newmarket, Richmond Hill and Yorkville. In a municipal sense,

this the present division, except that the Village of Yorkville was last

year admitted into the City of Toronto under the name of St. Pauls Ward.

The reader hardly needs

to be informed, however, that the municipal divisions are not identical

with the divisions for the purpose of Parliamentary representation. It

has been seen on a former page that in very early times one member was

considered sufficient to represent a tract of territory very much larger

than the present County of Yoik. To trace the progress of Parliamentary

representation for the County of York from that time down to the present

would occupy much space, and would be attended with very little benefit

or entertainment to the reader. It will be sufficient to begin with the

Union, at which date York was divided into four electoral Ridings, known

respectively as the First, Second, Third and Fourth Ridings. During the

First Parliament, which lasted from the 8th of Apr 1841, to the 23rd of

September, 1844, these constituencies were respectively represented by

James Hervey Price, George Duggan, Mr. James Edward Small, Robert

Baldwin, and Louis Hypolite Lafontaine. The Second Parliament lasted

from the 12th of November, 1844, to the 6th of December, 1847. Messieurs

Price, Duggan, and Baldwin continued to represent their various

constituencies. Mr. Small was reelected for the Third Riding, but his

return was declared null and void 011 the 14th of March, 1845, and his

opponent, George Monro, was declared to have been duly elected. Mr.

Monro accordingly represented the constituency from that time forward

until the close of the Second Parliament. As for Mr. Lafontaine, his

representation of an Upper Canadian constituency was merely a temporary

expedient, and after the close of the First Parliament he was returned

for the Lower Canadian constituency of Terrebonne. Before the assembly

of the Third Parliament a re-adjustment and re-naming of the

constituencies had taken place, and they were thenceforward respectively

known as the North, East, South and West Ridings. The North Riding

consisted of the townships of Brock, Georgina, East Gwihuiibury, North

Gwillimbury, Mara, Rama, Reach, Scott, Thorah, Uxbridge, and Whitchurch.

The Fast Riding was composed of the townships of Markham, Pickering,

Scarborough, and Whitby, The South Riding comprised the townships of

Etobicoke, King, Vaughan, and York ;. and the West Riding was made up of

the townships of Albion, Caledon, Chinguacousy, Toronto and the Gore of

Toronto. During the Third Parliament, which lasted from the 24th of

January, 1848, to the 6th of November, 1851, the North Riding was

represented by Robert Baldwin, the East Riding by William Hume Blake and

Peter Peiry, the South Riding by James Hervey Price, and the West Riding

by Joseph Curran Morrison. During the Fourth Parliament an Act was

passed increasing the representation to sixty-five members from each

section of the Province. Thenceforward York was divided into three

constituencies only, the North, East and West Ridings. Without

consecutively following the representation and divisions of the county

any further, it may be said that by the eighth section of the second

chapter of the Consolidated Statutes of Canada, the Count}'' of York is

divided into three Ridings, to be called respectively the North Riding,

the East Riding and the West Riding; the North Riding consisting of the

townships of King, Whitchurch, Georgina, East Gwdimbury and North

Gwilhmbury; the East Riding consisting of the townships of Markham,

Scarborough, and that portion of the Township of York lying east of

Yonge Street, and the Village of Yorkville; the West Riding consisting

of the Townships of Etobi coke, Vaughan, and that portion of the

Township of York lying west of \ onge Street. Py statute 45 Victoria,

chapter 3, passed on the 17th of May, 1882, entitled "An Act to

re-adjust the Representation m the House of Commons, and for other

purposes," it is enacted that the East Riding of the Count) of York

shall consist of the townships of East York (i.e., the portion lying

east of Yonge Street), Scarborough and Markham, and the villages of

Yorkville and Markham ; and that the North Ridingshall consist of the

townships of King, East Gwilhmbury, West Gwilhmbury, North Gwilhmbury

and Georgina, and the villages of Holland Landing, Bradford and Aurora.

Representation in the

Local Legislature is provided for by the eighth chapter of the Reused

Statutes of Ontario, entitled "An Act Respecting the Representation of

the People in the Legislative Assembly/' whereby it is provided that the

County of York shall be divided into three Ridings, to be called

respectively the North Riding, the East Riding and the West Riding; the

North Riding to consist of the townships of King, Whitchurch, Georgina,

East Gwill'mbiiry and North Gwilhmbury, and the Villages of Aurora,

Holland Landing and Newmarket; the East Riding to consist of the

townships of Markham and Scarborough, that portion of the Township of

York lying east of Yonge Street, and the villages of Yorkville and

Markham ; the West Riding to consist of the townships of Etobicoke and

Vaughan, that portion of the Tow nslrp of York lying west of Yonge

Street, and the Village of Richmond Hill Upon the admission of Yorkville

as a portion of the City of Toronto, in 1883, ii was specially provided

that the village should for Parliamentary purposes still remain attached

to the East Riding of York.

Independently of

territorial and Parliamentary divisions, there is not much to record in

the way of purely County history, beyond what is given in the various

Township histories which will be found elsewhere in this volume. The

County played a very conspicuous part in the Rebellion of 38' hut the

details of that dl starred movement are recorded at considerable length

-n the " Brief History of Canada and the Canadian People," with which

the reader of these pages may be presumed to be already familiar. The

merest outline is ail that can be attempted here. The public

dissatisfaction with the many abuses which existed in those days, and

with the high-handed tyranny of the executive, was intensified in 1836

and 1837 by the injudicious proceedings of the Lieutenant-Governor, Sir

Francis Bond Head. That dignitary employed the most corrupt means during

the elections of 1836 to secure the return of members favourable to his

policy, and the leading Reformers of Upper Canada were defeated at the

polls. The most shamelessly dishonest means were employed to secure the

defeat of William Lyon Mackenzie m the Second Riding of York, for which

constituency he had already been returned five times in succession, and

he had as often seen unjustly expelled from membership in the Assembly.

The combined tyranny and abuses of the time had long since aroused a

spirit of resistance, and before the year 1837 was many months old this

spirit had begun to assume an active shape. An enrolment of the

disaffected throughout the Second Riding took place, and the list

included many persons of the highest respectability and intelligence.

Mackenzie's paper, The Constitution, circulated largely throughout the

constituency, and his influence there was paramount. He and his

coadjutors made urgent and repeated inflammatory appeals to the people

of the Province generally, who ware incited to strike for that freedom

which could only be won at the point of the sword. A Central Vigilance

Committee was formed, and Mackenzie devoted all his time to the

organization of armed resistance to authority. Drillings were held at

night throughout nearly the whole of the northern part of the County of

York. It was at last settled that an attempt should be made to subvert

the Government. The time fixed upon for the commencement of hostilities

was Thursday, the 7th of December (1837), at which date the rebels were

to secretly assemble their forces at Montgomery's Tavern, a well-known

hostelry on Yonge Street, about three miles north of Toronto. Having

assembled, they were to proceed in a body into the city, where they

expected to be joined by a large proportion of the inhabitants. They

were to march direct to the City Hall, and seize 4000 stand of arms

which had been placed there. The insurrectionary programme further

included the seizure of U e Lieutenant-Governor himself and his chief

advisers, the capture of the garrison, and the calling of a convention

for the purpose of framing a constitution. A provisional government was

to be formed, at the head of which was to be placed Dr. John Rolph, one

of the ablest men who has ever taken part in Upper Canadian affairs.

The scheme promised

well enough, but there was no efficient organization among the

insurgents, who were from the beginning doomed to failure. The details

seem to have been largely deputed to Mr. Mackenzie's management, and if

active energy could have insured success at the outset, the insurgent

programme would have been fully carried out. Sir Francis Head, though

kept continually informed of treasonable meetings in various parts of

the Home District, treated all such intelligence with contempt, and made

no preparation to defend his little capital. There was absolutely no

possibility of failure on the part of Mackenzie and his forces, if they

had manifested the least ability for conducting an armed insurrection.

But the leaders had no common plan of operations, and were out of

harmony with each other. No one seems to have been invested with

undivided authority. Mackenzie reached the house of his friend and

co-worker Mr. David Gibson, in the neighbourhood of Montgomery's, on the

evening of Sunday, the 3rd of December, when, to quote his own words:

"To my astonishment and dismay, 1 was informed that though I had given

the captains of townships sealed orders for the Thursday following, the

Executive had ordered out the men beyond the Ridges to attend with their

arms next day (Monday) and that it was probable they were already on the

march. Instantly sent one of Mr. Gibson's servants to the north,

countermanded the Monday movement, and begged Colonel Lount not to come

down, nor in any way disturb the previous regular arrangement. . . . The

servant returned on Monday with a message from Mr. Lount that it was now

too late to stop; that the men were warned, and moving, with their guns

and pikes, on the march down Yonge Street—a distance of thirty or forty

miles, on the worst roads in the world—and that the object of their

rising could no longer be concealed. I was grieved, and so was Mr.

Gibson, but we had to make the best of it. Accordingly, 1 mounted my

horse in the afternoon, rode in towards the city, took five trusty men

with me, arrested several men on suspicion that they were going to Sir

Francis with information, placed a guard on Yonge Street, the main

northern avenue to Toronto, at Montgomery's, and another guard on a

parallel road, and told them to allow none to pass towards the city. I

then waited some time, expecting the Executive to arrive, but waited in

vain. No one came, and not even a message. I was therefore left in

entire ignorance of the condition of the capital, and, instead of

entering Toronto on Thursday with 4,000 or 5,000 men, was apparently

expected to take it on Monday with 200, wearied after a march of thirty

or forty miles through the mud, in the worst possible humour at finding

they had been called from the very extremity of the county, and no one

else warned at all."

This was certainly a

disheartening state of affairs, though as a simple matter of fact there

is no doubt that the city might easily have been taken vast then, even

with a less force than 200, if the rebels had been efficiently

commanded. But the change of date from Thursday to Monday seems to have

completely disheartened Mackenzie, who from that time forward seemed to

act without either energy or judgment. Instead of proceeding into the

city, he actually kept his forces at Montgomery's until Thursday in a

state of complete inaction. By that time the authorities in Toronto had

of course become aware of the movement. Assistance had been summoned

from Hamilton and elsewhere, .and all hopes of success for the

insurrection were at an end. On Thursday the loyalist forces advanced

northward and met the rebels a short distance north of Gallows Hill. A

skirmish followed, but was of very short duration, as the rebels were

altogether outnumbered, and fled in all directions. Mackenzie and the

other leaders succeeded in making their escape to the United States; all

except poor Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, who were captured and

executed at Toronto on the 12th of April following. Their remains are

interred in the Toronto Necropolis.

As, owing to their

tragical ending, much interest ,s felt in these unfortunate persons, it

may not be amiss to give some account of them. The following is

condensed and adapted from "Canada in 1837-38, a work written by Edward

Alexander Theller, an Irish-American citizen who acted as a

"Brigadier-General in the Canadian Republican Service." Samuel Lount was

born in the State of Pennsylvania, and lived there until he migrated to

Upper Canada, which event took place when he was about twenty-two or

twenty-three years of age. He settled near the shores of Lake Simcoe, in

what was then a wilderness. By industry and frugality he in course of a

few years amassed considerable property. To the many poor settlers wdio

came from Europe and obtained grants of land from the Government he was

a friend and adviser, and in cases of necessity he frequently supplied

their wants from his own purse or his own granaries. He saw and deplored

the many grievances which afflicted his adopted country. In 183411c was

elected a member of the Provincial Assembly, in which he served until

1836, when, owing to the machinations of Sir Francis Head and his

advisers (who did not scruple to employ the most corrupt means to

achieve such a result), he was defeated at the polls by a brother of

Chief Justice Robinson. Like Mackenzie, Rolph and other leaders of the

Reform party, he despaired of accomplishing anything of importance by

further constitutional agitation, so he allied himself with the

insurrectionary movement, and marched a body of men to Montgomery's.

When the collapse of the movement came, he fled, with others, to the

neighbourhood of Gait, whence, accompanied by a friend named Kennedy, he

made his way to the shores of Lake Erie. Having secured a boat, they

attempted to cross to the United States, but their little craft was

driven ashore by floating ice. They were at once captured and forwarded

to headquarters at Chippewa, where Colonel MacNab's camp was. Lount had

no sooner reached Chippewa than he was recognized. He was next sent to

Toronto and placed in jail until his trial. There was no question as to

his guilt, in a legal and technical sense, and he attempted no defence.

He was found guilty, and sentenced to death. The sequel has already been

told.

Peter Matthews was a

wealthy farmer, possessed of great influence among the people in the

neighbourhood of his residence. He had served as a Lieutenant in the

incorporated militia of the Province during the War of 1812, '13 and

'14, and had signalized himself by his bravery. He made common cause

with Mackenzie and Lount, and raised a corps in the neighbourhood of his

home, at whose head he marched to Montgomery's. On the morning of that

fatal Thursday he proceeded with a company of men to the Don Bridge, for

the purpose of creating a diversion in the east end of the city. While

there he heard the noise of the engagement at Montgomery's, and was

compelled to vacate his position. He fled from the scene, and took

refuge in the house of a friend, where, a few days later, he was

discovered and captured. He adopted the same policy as Lount, and made

no defence. He suffered the extreme penalty of the law, as has already

been related. "He was," says Theller, "a large, fleshy man, and had much

of the soldier in his composition; and sure am I that he demeaned

himself like one, and died like a man who feared not to meet his God."

Mackenzie, in his "Caroline Almanac," bears testimony to the same

effect. "They behaved," he remarks, "with great resolution at the

gallows; they would not have spoken to the people had they desired. He

adds: "the spectacle of Lount after the execution was the most shock ing

sight that can be imagined. He was covered over with his blood, the head

being nearly severed from his body, owing to the depth of the fall. More

horrible to relate, when he was cut down, two ruffians seized the end of

the rope and dragged the mangled corpse along the ground into the jail

yard, some one exclaiming: This is the way every d—d rebel deserves to

be used.

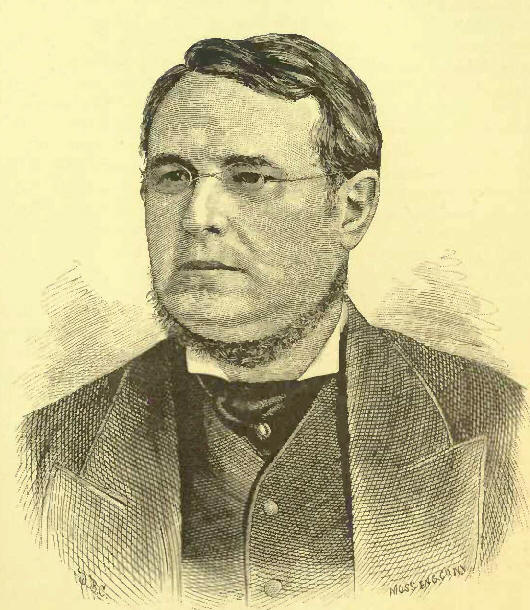

HON. EDWARD BLAKE.

A word upon the subject

of Gallows Hill, near which the engagement between the loyal and

insurrectionary troops took place. Every "person living in or near

Toronto is fami1 ar with the spot, but comparatively few are acquainted

with the tragical circumstances to which it is indebted for the name it

bears. In the early years of the present century a rude wagon track

ascended the hill a short distance west of where the road now&is. Near

the top was a narrow notch, with high banks on each side, caused by

excavations. Lying directly across the notch, and at a sufficient height

to admit of the passing of loaded wagons beneath, was a huge tree, which

had been blown down by a violent storm, and which lay there undisturbed

for many years. In the late twilight of a summer evening a belated

farmer, driving home from attending market at York, was horrified to

find ari unknown man hanging by a rope from the tree which spanned the

roadway. No clue was ever obtained, either as to the identity of the

man. or as to the circumstances under which he met his death, though it

was commonly believed that he must have committed suicide. The name of

Gallows Hill soon afterwards came into vogue as applied to the spot, and

it has been perpetuated ever since. Such is the origin of a phrase which

has been a household word in and around the Upper Canadian capital for

more than seventy years. |