|

THE year 1860 was

marked by two notable events—the visit of mf H. R. H. the Prince of

Wales, and the Anderson Extradition Case. The first of these took place

early in September, and was occasion of festivities on a scale seldom,

if ever, equalled in Toronto. The Prince, accompanied by the Duke of

Newcastle, Colonial Secretary, the Governor-General, Sir Edmund Head,

and a numerous suite, reached Toronto from the east on the 7th of

September. For days and weeks previous the citizens had been busy with

preparations to do honour to the Royal visitor; a series of magnificent

triumphal arches had been erected on the streets, flags and bunting in

immense quantities had been purchased, addresses had been drawn up,

programmes of banquets and entertainments prepared—in fact neither

trouble nor expense had been spared to make Toronto's reception of the

Prince a brilliant and splendid affair. At half-past six o'clock in the

evening of the 7th of September the steamer Kingston, with the Roval

party on board, reached the landing-place at the foot of John Street,

where a huge amphitheatre had been erected and was now crowded by

thousands of the wealth and fashion of the city. The roadway from the

landing-place to the Esplanade—where a handsome arch had been

erected—was also lined with tiers of seats, in which not a vacant space

was to be found, while the entire neighbourhood was black with eager and

loyal people, who, undaunted by the threatening aspect of the sky, had

turned out to do honour to the city's Royal guest. As the Kingston

approached the wharf a storm of cheers broke from the assembled

multitudes. The Prince, on leaving the steamer, was received by the city

magnates, and an address of welcome was read by the Major, Mr. Wilson.

When the Prince had replied, over a thousand children of the Public and

Sunday schools, who had been specially trained for the occasion, raised

the strains of the National Anthem. The Prince and the Governor-General

were driven to Government House, which had been specially prepared for

their reception. In the evening the city was brilliantly illuminated,

and the royal party drove through the streets amidst the cheers and

acclamations of a vast crowd. The Globe, speaking of the illuminations

at the time declared that" As a whole it is doubted if the display of

that night was ever excelled in America in extent, variety, and

brilliancy of decoration. Speaking of the arches the same journal

remarked: "The arch erected on the crest of the amphitheatre at the

landing will be a lasting monument to the fame of its designer, Mr.

Storm. Fine as were the arches erected at Quebec, Montreal and Ottawa,

the finest of them could not for a moment enter into competition with

it.'"

It would be impossible,

in the space at our disposal, to give anything like an account of the

festivities during the Prince's stay—from the 7th to the 12th. The

entire six days, were one prolonged. The principal features of this

carnival time were a levé at Osgoode Hall, a regatta on the bay, a

review of the active militia force, a visit to the University, and the

formal opening of the Horticultural Gardens by His Royal Highness, who

planted there a young maple which still flourishes, though no longer

young. During his visit the Prince also made a huried trip to

Collingswood, and on the 12th bid the city farewell.

The only untoward event

which occurred during the Prince's stay was a foolish escapade by a few

young hot-heads who assembled on Colborne Street and burnt in effigy the

Duke of Newcastle and Sir Edmund Head. The objects of the demonstration

having set their faces against the exuberant Orange decorations at

Kingston and Belleville, the effigy-burners resorted to this method of

expressing their dissatisfaction.

The second event which

signalized the year 1860—the Anderson Case —was one which will long be

remembered for the intense interest it awakened throughout the length

and breadth of Canada, and scarcely less in Great Britain. Anderson was

a runaway slave from Missouri, who, while making his way to Canada, slew

a man named Diggs, who was in pursurt with intent to capture him. In

April, in the year mentioned, a man who had tracked Anderson to this

country caused his arrest for murder, with a view to extradition. The

case came up at the Michaelmas Term of the Court of Queen's Bench, on a

writ of habeas corpus, Anderson being defended by leading members of the

Bar—for such was the excitement throughout the country that funds poured

in for his defence. The decision of the Court—one of the three Judges

dissenting—was in favour of the surrender of the prisoner. Anderson's

counsel, however, determined to .make a further effort, and a writ of

habeas corpus was obtained from the Court of Queen's Bench in England to

bring the prisoner before the Judges there.

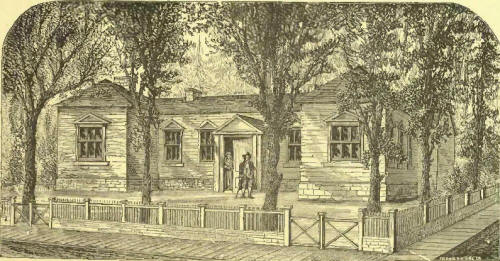

RUSSELL ABBEY.

A decision in his

favour from that quarter being beyond a doubt. A conflict between the

British and Canadian Courts seemed imminent, but fortunately was avoided

by the issue of a third writ of habeas corpus from the Upper Canadian

Court of Common Pleas, which liberated the prisoner upon a technicality,

without entering into the merits of the case. The excitement which had

prevailed while Anderson's case was still stib judice was only equalled

in intensity by the rejoicings over his release. The coloured community

was especially jubilant; but the whole of Canada, Great Britain, and

even New England, shared in their satisfaction.

The breaking up of the

ice in the Don in the spring of the following year (1861) solved a

mystery which for sixteen months had seemed impenetrable. A battered,

bruised and partially decomposed body was discovered in the water near

the mouth of the little river, entangled in some weeds. Upon examination

it was identified as that of John Sheridan Hogan, a prominent Toronto

journalist and Reform member of the Legislature for the County of Grey,

who had unaccountably disappeared in December, 1859. No end of theories

had been broached to account for his disappearance— among others that he

had tied to the United States to avoid the importunities of his

creditors ; but the idea that he might have been foully dealt with does

not seem to have struck the public mind. Such, however, upon

investigation, proved to have been the case. From the evidence it

appeared that on the night of his disappearance the murdered man crossed

the Don bridge in pursuance of an intention to visit a friend who lived

on the Kingston Road. When in the act of crossing the bridge he was

accosted by a woman who engaged him in conversation, while a second

female struck him on the head with a stone placed in the foot of a

stocking. Both women belonged to a notorious band of ruffians who

infested a wood on the east side of the Don—from which they took their

name, the Brooks' Bush Gang. Other members of the gang then came up, a

considerable sum of money was taken from the body of the murdered man,

and the body itself was thrown over the bridge railing into the river.

Although several members of the gar were arrested, there can be no

manner of doubt that the really guilty parties escaped punishment, while

a comparatively innocent man underwent the extreme penalty of the law.

One of the ruffianly set turned Queen's evidence, others succeeded in

proving an alibi, while one, named Brown, less successful, was found

guilty and hanged. Brown, although present at the murder, does not seem

to have had any actual hand m it. The revelations at the trial had the

effect of completely dispersing the gang, one member of which, 18 an

infamous woman, is now said to be a notorious resident of Buffalo.

Another member, also a woman, was, until comparatively lately, an inmate

of Toronto gaol.

The year 1861 witnessed

the death of William Lyon Mackenzie, one of the most prominent figures

in the history of the city of which he was the first Chief Magistrate.

The story of the great agitator's declining years is a sad one. From the

time of his return to Toronto in 1849, he continued to reside there till

his death, supporting himself chiefly by journalism. From 1851 to 1858

he represented the County of Haldimand in the Provincial Legislature,

but in the latter year he resigned his seat, and devoted himself

entirely to the management of his journal, Mackenzie's Weekly Message.

The profits, however, were small, and the editor's life was one of

hardship, debt, and deprivation. Some of his Reform friends, becoming

aware of his unfortunate situation, opened a subscription—ostensibly for

the purpose of presenting him with a testimonial in recognition of his

services; really with the object of relieving his necessities—not an

easy object to attain without wounding his feelings of independence and

self-respect. A considerable amount was raised, and with a portion of

this a house and lot on Bond Street were purchased and presented to Mr.

Mackenzie. Another sum was handed to him as a loan—nominally, of

course—by the subscription committee; bur as no small part of this was

employed by him in paying debts, it was not long before he was again in

distress. But the end was not far off. Utterly broken down in body and

mind, careless of the approach of death, refusing medical aid, the great

Reformer gradually sank, till, on the 28th of August, death put an end

to the restless, busy life—within less than four years of the allotted

span of three-score and ten.

Towards the close of

1861, Toronto was in a ferment. The seizure of the Confederate envoys,

Messrs. Mason and Slidell, on board the British mail steamer Trent, had

just taken place, and every one was discussing the probabilities of a

war with the United States. The entire population seemed to burn with a

sudden military ardour; thousands of volunteers enrolled themselves as

recruits ; drill was a regular every day matter; new companies. were

added to existing regiments ; and speculations were freely indulged in

as to the probability of Toronto becoming the great military centre for

Upper Canada, and even a naval station, in view of the probability of

operations by water. Sympathy with the South, in which, previous to the

Trent affair, the citizens of Toronto, like Canadians generally, were by

no means a unit, now became general, and a war with the United States

would have been extremely popular. Happily there was no occasion to put

to the test the enthusiasm of Canadians; the Confederate envoys were

surrendered, and the excitement in Toronto, as elsewhere, cooled down.

But the seed had been sown, the emergency had taught the people a

lesson; and from the crisis brought about by the Trent affair, the

military spirit which has given Canada its present militia force may be

said to date.

Outside of the events

just related, the local history of Toronto from i860 to 1865 was that of

the proverbial happy country that has no history. The close of the

decade of the fifties had witnessed commercial depression, stagnation in

trade and manufactures, starvation and misery. The first half of the

decade of the sixties brought commercial vigour, activity in trade and

manufactures, abundance and prosperity. It was the story of Pharaoh's

reversed. The cause of this state of things was to be looked for in the

American civil war. The country was overrun with commissariat agents

purchasing stores for the army. American gold poured in, in a stead)

stream, and produce of all kinds could not be supplied with sufficient

rapidity to meet the demand. Farmers and merchants—wholesale and retail—

reaped a golden harvest, and many a fortune was accumulated by trader

and speculator. Toronto of course had its share of the general activity,

and the condition of the city, in those days when war prices ruled, was

one of unexampled prosperity.

We now come to one of

the saddest chapters in the whole of Toronto's history—a story of events

winch threw the entire city into mourning. During the morning of Friday,

the 1st of June, 1866, intelligence was received mi the city that a body

of one thousand Fenians had crossed the Niagara River at Black Rock,

landed near Fort Erie, and were ravaging the country in the Vicinity.

Regular troops were at once despatched to the spot, and the city

volunteers were called upon to furnish their quota to repel the invader.

It was now that the military spirit evoked among the citizens during the

Trent excitement came into play. The call was promptly responded to, and

by two o'clock in the afternoon a force of six hundred men of the

Queen's Own—many of them University students— had embarked on board the

steamer City of Toronto, which was to convey them across the lake. The

force was under the command of Major Gillmor, and consisted mainly of

young men. With what happened on the banks of the Niagara River we have

nothing to do here—it is matter of Canadian history, with which every

Canadian is familiar. A conflict took place at Ridgeway, the brunt of

which had to be borne by the volunteers, owing to the failure of the

regulars to put in an appearance 111 time, and some of the Toronto

contingent lost their lives on the battle-field. The news, in an

imperfect form, reached the city on the Sabbath morning and it was a sad

Sabbath that the Toronto people spent. A writer m the 'Varsity for June

2nd, 1883, gives the following graphic description of that memorable

day: "That Sunday was one such as Toronto had never seen before. The

most contradictory rumours were afloat m the city, /he churches

presented a most extraordinary spectacle. Instead ot the usual

attendance of quiet worshippers-of the hymn of praise, the calm

discourse-the attendant throng was assembled in deep humiliation and

earnest prayer. I doubt whether a single sermon was preached in Toronto

that day. Excited people came rushing into the churches and announcing

the latest news from the front. Then a prayer would be offered up by the

pastor, or the congregation would bow their heads in silent

supplication. The merchants, on lord being received that the volunteers

were suffering from want of food, ransacked their warehouses for

supplies to be sent to the front by the steamer that was to go to Port

Palhousie that afternoon for the dead and wounded; and all the young men

were hastening to the from.

About ten o'clock that

night the steamer above alluded to, with her mournful freight, reached

the Yonge Street wharf, where an immense throng had congregated, and

where several hearses and stretchers borne by men of the 47th Regiment

were in waiting. A writer in the Globe of the following day thus

describes the scene on board the steamer: "At one end of the vessel lay

arranged together the rough coffins enclosing the dead. Near the other,

laid on couches and shakedowns, tenderly and thoughtfully cared for,

were the wounded. No word of complaint escaped them as they were

severally moved by strong arms and feeling hearts to the cab or the

stretcher., as their case might require. Ten were .severely wounded and

were carefully sent to the hospital; the. remainder were sent to their

respective homes. While the wounded were being thus disposed of, the

dead were deposited in hearses and carried to their several

destinations. The coffins in which they were enclosed were formed of

rough plain timber, the name of the sleeping occupant being chalked on

the cover." The following are the names of ihe dead who were brought to

the city: Ensign Malcolm McEachren, No. 8 Company, Q.O.R.; Private

Christopher Alderson, No. 7 Company; Private William Fairbanks Tempest,

No. 9 Company; Private Mark Defries, No. 3 Company; and Private William

Smith, No. 3 Company.

On the following

Tuesday, the 5th, the remains of the five heroes were accorded the

honours of a public funeral. During the forenoon of that day the five

bodies lay in state in the Drill-shed, which was draped m black, the

coffins being covered by flags. About four o'clock the procession

started for the cemetery, headed by the band of the 47th Regiment.

Following the private mourners came the funeral committee, the troops—

regular and volunteer—the mayor and corporation, and a long procession

of citizens on foot and in carriages. All the shops were shut, the bells

tolled, the streets were lined by silent crowds, many people wearing

badges of mourning. And so the solemn procession wended its way to St.

James's Cemetery, where the bodies were committed to the earth.

A week after the

funeral two of the wounded, Sergeant Hugh Matheson and Corporal F.

Lackey, of No. 2 Company, Queen's Own, succumbed to their injuries. They

also were buried with public honours. In addition to these, two other

members of the regiment, who were not residents of Toronto, had fallen

on the battle-field, and were burled at the places to which they

respectively belonged. Thus the total death-roll of the Queen's Own on

this fatal occasion was nine. It is almost unnecessary to add that their

devotion to their country was suitably honoured. Pensions were granted

by the Province to the bereaved widows and orphans, and the monument in

the Queen's Park—of which a description will appear hi its proper

place—testifies to the loving regret with which the country cherishes

the memory of her devoted sons.

The Chief Magistrate of

the city in these stirring times was Mr. Francis H. Medcalf, who had

succeeded Mr. Bowes in 1864, and who retained office until the close of

1866. In the latter year the municipal law of the Province again

underwent a change. The election of mayors in cities by popular vote was

discontinued, and a return was made to the system of election by the

Council. The office of councilman was also abolished, and three aldermen

were allowed to each ward. The first Mayor of Toronto elected under the

new Act was Mr. James E. Smilh, in 1867. |