|

LORD SELKIRK - THE FRENCH -

THE POLLY - LAND TENURE

When Jacques Cartier, on

June 20, 1534, discovered L'Isle St. Jean, the present Prince Edward

Island, he found the trees there "Marvellously beautiful and pleasant in

odour - cedars, pines, yews, white elms, ash trees, willows and others

unknown. Where the land was clear of trees it was good, and abounded in

red and white gooseberries, peas, strawberries, raspberries, and wild

corn, like rye, having almost the appearance of cultivation. The climate

was most pleasant and warm. There were doves and pigeons and many other

birds."

Since then North America

has been settled almost entirely by peaceful pioneer groups and

individuals, mainly seeking greater freedom, either civil or religious, or

wider opportunities for economic advancement. They and their descendants

have, in three centuries, transformed a continent. They found a wild waste

of dismal swamp and gloomy forest, abode of stealthy savage and majestic

deer; treeless plain, alternately scorched by summer's blistering sun and

chilled by winter's bitter blast; dark forbidding mountain, temple of

mystery. Where once the buffalo roamed in thundering millions the settler

now garners crops of golden corn. The iron rail and metalled road displace

the labored oar. Nature has been subdued and broken by the will of man,

and today these wastes of yesterday provide the happy home of many

millions. The cost in human toil and anguish of this, an accomplishment so

stupendous, can be estimated only by such as reckon the vast number of

those that shared the toil and now lie sleeping in Earth's bosom.

A settlement of Highland

Scots is believed to have been made in North Carolina as early as 1739.

Following the collapse of the rebellion in 1745, and the breaking down of

the clan system, a great wave of emigration from the Highlands of Scotland

set in. Fifty-four vessels full of emigrants from the Western Isles and

the Highlands sailed for North Carolina between April and July, 1770. In

1772 the great Macdonald emigration began and lasted until the outbreak of

the Revolutionary War in 1776. Boswell in his "Journal of a

Tour of the Western Islands" made with Johnson in 1773, refers to the

eager enthusiasm of the people to emigrate to the American Colonies. Up to

this time no emigrant from Skye had ever gone elsewhere than to North

Carolina. Many people in the Belfast district in Prince Edward Island, are

kinsmen of the Scots in that State.

In 1771 James Macdonald,

merchant, Portree (Skeabost), and Norman Macdonald of Slate (Scalpa), for

themselves and on behalf of Hugh Macdonald, of Armadale, Edmund Macqueen,

John Betton, Alexander Macqueen of Slate, Rev. William Macqueen of Snizort,

and Alexander Macdonald of Cuidrach, in Skye, petitioned the King's

Majesty in Council for a grant of 40,000 acres of land in North Carolina,

upon the usual terms and conditions of such grants. The petition was

dismissed 19th June, 1772, by the Privy Council Committee on Plantation

affairs on the ground that it was not desirable that so many people should

leave the country.

The Revolutionary War put a

temporary stop to the exodus to North Carolina. The Colony, however, was

established firmly, and friends in the homeland soon began to join their

kinsmen beyond the seas, regardless of the political separation from the

Motherland.

The social unrest at the

time of the American and the French Revolutions and the economic

depression during and after the Napoleonic Wars, added further incentive

to the already all-too-eager desire to emigrate, and by 1805 large numbers

were departing to join their relatives and friends in the Carolinas.

During the period of this

great emigration the Army claimed many recruits, and Skye men played a

great part in deciding England's destiny on the field of battle. From

about 1797 to 1837 it is computed that ten thousand private soldiers, six

hundred commissioned officers under the rank of Colonel, forty-five

Lieutenant-Colonels, twenty-one Lieutenant-Generals and Major-Generals,

and one hundred and twenty pipers from the Isle of Skye were in the

British Army. Skye, during the same period, gave four Governors of British

Colonies, one Governor-General of India, and one Adjutant-General to the

British Army In the Battle of Waterloo it is computed sixteen hundred

Skyemen fought in the British ranks.

In 1771 Thomas Douglas,

youngest of the seven sons of the 4th Earl of Selkirk, was born. By 1799

his father and all his brothers were dead and he had succeeded to the

title. He was destined for the law, and in Edinburgh was an associate of

Jeffrey, Fergusson, Scott, and others of the leading spirits in that

shining age. He was deeply interested in the problems of his time, and

longed to ameliorate the hard lot of his fellow countrymen. He spent ten

years abroad in travel and study, and in 1802, on his return home,

proposed a national scheme designed to remedy the social unrest. The next

eight years, from 1802 to 1811, were spent by him in an effort to divert

the tide of emigration from the Carolinas to Eastern Canada. Thereafter

his life was occupied in his endeavors to found the Selkirk Colony on the

banks of the Red River. He wished his fellow countrymen to establish

themselves in circumstances providing full scope for their industry, and

under the British flag. He first directed his efforts to Prince Edward

Island. Three ships were chartered and about eight hundred passengers

embarked to found a new home on his estate on this island. The "Polly" had

the greatest number of passengers, most of whom were from Skye. On her was

Dr. Angus MacAuley, agent for Selkirk. She arrived in Orwell Bay, Prince

Edward Island, on Sunday, August 7, 1803, and disembarked her passengers

near the present Halliday's Wharf. The "Dykes" arrived on August 9, and

the "Oughton" with the Uist men on August 27. At this time the total

population of the island was but little over five thousand. Selkirk, who

was a passenger on the "Dykes," had planned to arrive before the others so

that preparations might be made for their reception, but before he

appeared on the scene the "Polly" had disembarked her complement. "I

arrived," he writes, "late in the evening, and it had then a very striking

appearance. Each family had kindled a large fire near their wigwams, and

round these were assembled groups of figures, whose peculiar national

dress added to the singularity of the surrounding scene. Confused heaps of

baggage were everywhere piled together beside their wild habitations, and

by the number of fires the whole woods were illuminated. At the end of

this line of encampment I pitched my own tent, and was surrounded in the

morning by a numerous assemblage of people whose behaviour indicated that

they looked to nothing less than a restoration of the happy days of

Clanship-" To obviate the terrors which the woods were calculated to

inspire, the settlement was not dispersed, as those of the Americans

usually are, over a large tract of country, but concentrated within a

moderate space. The lots were laid out in such a manner that there were

generally four or five families, and sometimes more, who built their

houses in a little knot together; the distance between the adjacent

hamlets seldom exceeding a mile.

Each of them was inhabited

by persons nearly related, who sometimes carried on their work in common,

or at least were always at hand to come to each other's assistance.

"The settlers had every

inducement to vigorous exertion from the nature of their tenures. They

were allowed to purchase in fee simple, and to a certain extent on credit;

from fifty to one hundred and fifty acres were allotted to each family at

a very moderate price, but none was given gratuitously. To accommodate

those who had no superfluity of capital they were not required to pay the

price in full till the third or fourth year of their possession.

"I left the Island in

September, 1803, and after an extensive tour on the continent, returned in

the end of the same month the following year. It was with the utmost

satisfaction I then found that my plans had been followed up with

attention and judgment.

"I found the settlers

engaged in securing the harvest which their industry had produced. They

had a small proportion of grain, of various kinds, but potatoes were the

principal crop. These were of excellent quality, and would have been alone

sufficient for the entire support of the settlement."

That his schemes of

settlement were to be a panacea for all the ills disturbing the State was

not the expectation of the generous-minded Selkirk. "I will not assert,"

he says, "that the people I took there have totally escaped all

difficulties and discouragements, but the arrangements for their

accommodation have had so much success that few people perhaps in their

situation have suffered less, or have seen their difficulties so soon at

an end."

Although the circumstances

under which Lord Selkirk settled the Red River district in Rupert's Land,

and the Belfast district in Prince Edward Island had much similarity, the

peculiar isolation under which the Red River settlers lived for upwards of

sixty or seventy years led to an intense loyalty to the founder of the

colony, and to the colony itself as a social and political institution. A

thousand miles of wilderness, of lakes, forests, and rivers, lay to the

east; the great plains to the south and west, occupied by warring tribes

of hostile Indians. There was left one road only of ingress to and egress

from the colony. This meant a trying journey by boat and canoe from the

settlement through Lake Winnipeg, and the Hayes or the Nelson River to

Hudson's Bay. From there, an ocean voyage in stormy ice-beset northern

latitudes to England. All but the bravest shrank from such a journey. From

1812 until 1870 the Selkirk colonists on the banks of the Red River lived

largely unto themselves, and to this day they are as loyal to the Selkirk

settlement and to the Selkirk tradition as is any Highlander to his clan

chief.

Not so the Selkirk colony

on Prince Edward Island. Three years before they arrived the total

population of the Island was about five thousand; that of Charlottetown

about two hundred and fifty to three hundred. Only a few miles distant

from them to the north, a settlement of Loyalists from the American

colonies had been founded along Vernon river in 1792. They preferred to

endure the hardships incident to founding a new home in the virgin forest

under the flag they loved, than live under a government they regarded as

alien to the political principles they espoused. The Selkirk colonists,

after a generation, ceased to look upon themselves as a separate

institution, and merged their lives in the larger life of the little

province in which they lived. Today the Selkirk tradition is largely

forgotten except by those who pursue it historically for intellectual

diversion.

In culture and civilization

the Scots and Irish were much behind the English. Even to this day they

have not reached the same degree of culture as their more wealthy

neighbors. Owing to the poverty of his country the Highlander is unable to

acquire many of the comforts essential to cultural development. From a

state almost bordering on naked barbarism, in a comparatively short time,

they had settled down to an ordered social life. Even before the great

migration began after "the Forty-five" raids on neighboring clans to

avenge either some real or fancied personal or clan injury, or to fill the

empty larder, had become of but infrequent occurrence.

Steady unremitting toil is

alien to the Highland nature. The drudgery of the farm makes less appeal

to him than does work in the mysterious forest, on the changing ocean, or

in any other calling responsive to a spirit emotional and imaginative. His

highly sensitive and superstitious nature, tinged with brooding

melancholy, requires change and diversity. As a consequence we find him at

his best in a vocation which appeals to his restless spirit, and makes

frequent calls upon his ardent sentiment and ready intuition. Seafaring,

because the Viking ancestral spirit is in his blood, and the learned

professions, because of the diversity of work, suit him best. In these he

has been a notable success, and has left the imprint of sturdy Scottish

character and Scottish integrity upon society in every part of the world

in which his lot has been cast, and where duty has called him.

How much these qualities in

the Scot have had to do with the success of the major public enterprises

in Canada is a matter of interesting speculation. The Scot himself may

claim the chief honor. Many others will willingly grant him a very large

share of the credit where success has been achieved. Certainly in the

opening up and development of Canada, and of Western Canada in particular,

the Scot has played a dominant part.

In the City of London,

under the presidency of that swashbuckling ruffian, Rupert of the Rhine,

there was incorporated on the 2nd of May, 1670, "the Governor and Company

of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay." Being primarily fur

traders this Company strove to retain for themselves, as was their legal

right, exclusive control of the trade of the vast territories granted to

them. They always looked askance at settlement, and regarded with jealous

eye the advent of anyone from outside their employ. It is true that their

policy retarded the settlement and development of the country for

generations, and that of late years it has been the practice, though an

unworthy one, to disregard their monumental services to Canada, and,

ignoring history, to condemn the Company, as if in their long and enviable

record there was nothing to commend. In the annals of trade and commerce

the name "Hudson's Bay Company" will ever stand apart, conspicuous alike

in romance of origin and honorable achievement. A beacon of honesty for

more than al quarter of a thousand years, it has stood between the

rapacity of the white man and the credulity of the simple minded native,

to whom it has ever been the visible token and symbol of justice, of

humanity, and of fair dealing. The "true and absolute Lords and

Proprietors," it set and adhered to a fixed standard of barter between

itself and those over whose lives it was Destiny personified. By frugal

distribution it raised the supply of food and clothing, the absolute

necessities of human life, from precarious uncertainty to definite

certainty, and thereby saved the simple minded native from the misery and

degradation of alternate feast and famine.

To the poor Indian, whose

standard of living has been fixed by an unchanging system of just and

honest exchange for hundreds of years, the advantage has been

incalculable. The assurance of certain and ample reward for service, the

unvarying justice, the fixity of value in the system of barter, raised him

from a creature of momentary splendor and as swift poverty, to definite

self respectability and dignity. Nor has the world ever seen a more

fitting and constant appreciation and return for paternal care and self

assumed responsibility on the part of the Company than it has received

from its willing wards during the full course of its beneficent history.

True to its watchword -pro pelle cutem - the Company soon became, as

indeed it was and continued to be in the person of its agents, the

physical symbol of justice, order and authority. In place of the frequent

outbreaks of cruel lawlessness and open warfare between the red and the

white man, so common in regions less fortunately governed, and not so far

distant, there is here presented the spectacle of an institution, with

posts scattered over a territory ranging from two thousand to three

thousand miles square, manned by a few whites, living with the natives not

only in peaceful harmony and perfect safety, but on terms of willingly

admitted superiority and authority. Nor in the long history of the Company

has this moral authority ever been challenged. Rarely, if ever, has the

fair name "Hudson's Bay Company" been besmirched by cruelty, injustice or

fraudulent practice. Never has the sovereign power of which it was the

visible agent, been demeaned in the eye of the credulous native by any

lawless act of theirs. Not by statutory authority, but rather by humane

treatment and fair dealing, did it become the living symbol of British

authority, and of British justice, and as such was it recognized by them.

In estimating the honorable part which this great Company has played in

preserving huge territories to the nation, and attempting to hold other

valuable areas which were lost through causes not within its control,

tribute in unstinted measure must be paid to that noble band of Scots who,

since they first entered the e Company's employ to the present day, have

been recruited and sent overseas to man those remote outposts of Empire in

the hidden wastes of a vast continent, unseen and unheard except by those

whose destiny they held in sacred trust. Whatever the future may hold in

store for fair Scotia, those of her blood may look back with unfeigned

pride upon the record of her sons' great share in guiding the Company's

affairs with success so signal, and in moulding the early life of a new

nation on the sure footing of justice, law and order.

This humane and historic

Company, throughout its whole career, adapted itself to changing

circumstances and surroundings. It assumes new shape and form to meet the

varied circumstances of the passing hour, and thus lives on, symbol of an

honored past and inspiration to a greater future.

Intimately connected with

this Company is that other great institution carried on with unvarying

success through a period of over a century by men largely of Scottish

blood and tradition - The Bank of Montreal.

It commands a position of

the highest honor not only in Canada, but in the world. The cardinal

policy of this bank through the whole course of its long existence has

been never to compromise fundamentals for any questionable gain, however

great. On this firm foundation the sagacity of its directors and managers

has built up an institution which today is an honor to the foresight of

its counsels, to the character of the people, and to the Government of

Canada.

The same Scottish tradition

inspired the founding and guided the early operation of that other great

institution, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The fact that men of

Scottish race have fashioned these three world-encompassing institutions

brings a glow of well merited pride to the cheek of everyone possessing

Scottish blood.

Being an enlightened

reformer Selkirk threw the greatest possible responsibility on the

shoulders of the settler, and "the industry of the individual settler was

allowed full scope to exert itself."

The Island had been divided

into sixty-six Lots or Townships. In 1767 it was granted to various

persons, some of whom were officers in the Army and Navy, others were

merchants and members of Parliament. These Lots, which were acquired by

ballot, went in some cases to one person, in others to several. When one

person was to get a whole Lot his name alone appeared on a slip of paper,

otherwise several names appeared on the slip as sharers in one Lot. Lot 57

fell to Sam Smith and Captain James Smith, R.N. of the "Seahorse." It

later became part of the Selkirk Estate, and on the shore of this Lot the

Scottish settlement was made in 1803. Lot 50, adjoining, fell by lot to

Lieut.-Colonel H. Gladwin and Peter Innis. The various proprietors were

required to settle the land, but few carried out the conditions of the

grant. The quit rents to which these lands were subject were adjusted on

the basis of 6s., 4s. and 2s. per hundred acres. For the first five years

after the grant no quit rents were payable. For the next five years

one-half the fixed rents were payable. After ten years the whole amount

was payable. Even though these rents were later reduced, they were still

an intolerable burden on the new settlers, and for generations there was a

growing discontent with the leasehold tenure of land, culminating in an

agitation of such intensity that it was not stilled until 1860, when the

Government appointed a commission of enquiry. This led to the Government

purchase of the land from the landlords, and the sale of it to the various

purchasers. Leasehold tenure was changed to freehold, and with its

assurance of permanency the owner had every incentive to improve his

property. This he speedily did, with results so satisfactory that material

prosperity and mental content advanced hand in hand. In 1860 the Selkirk

Estates in Lots 53, 57, 58, 59. 60 and 62, containing 62,059 acres, were

purchased by the Government for £6,386 17s. 8d. sterling, or £ 9,880 6s.

6d. currency.

The settlement, afterwards

called Belfast, a corruption of the French "La Belle Face," was founded on

the abandoned site of a French colony whose members were deported to

France after the surrender of Louisburg in 1758. Their settlement extended

along the coves and creeks from the mouth of Charlottetown harbor to the

Pinette River. A French naval officer who visited the various French

settlements on the Island in 1752 reported that the number of settlers in

this area was not less than five hundred. Later the whole territory from

Vernon River to Wood Islands extending inland a few miles was, and is now

known generally as, the Belfast District.

The clearing had again

grown up, but various evidences of the former occupation, the shallow

well, the ditch, still existed. The old cemetery that knew the voice of

the Cure, M. Gerard, with its pathetic reminders of the transitory career

of man, was soon requisitioned by the newcomers to fill the purposes for

which it was dedicated, and today former members of a district settled

with similar hopes, but alien in race and religion, sleep in undisturbed

repose within the sacred confines of the common hallowed spot.

The majority of the 1803

settlers were from Skye, a fact of high significance. In that inhospitable

island, from the dawn of its recorded history, was bred a race of men and

women of unconquerable will and indomitable spirit. They were inured to

hardship and unspoiled by luxury. Living in a land distant and

inaccessible, they there maintained in their isolation, to an unusual

degree, racial purity and distinctive racial characteristics. These

qualities were carried across the seas to America, and there they were

further developed. In the environment peculiar to their island, Skyemen

developed into a military aristocracy undaunted by hardship or danger.

Having been tried in the fires of adversity for generations they were a

band well chosen to tame the arrogance of nature in the forests of

Belfast. But this was not accomplished without toil and self-denial

unknown to those who attempt a similar work in an age ministered to by all

the comforts provided by modern science. The isolation of their new home,

and the persistent intermarriage between members of the same stock, have

tended to maintain those characteristics peculiar to them, to a degree

almost unknown in other parts of English speaking Canada.

Although the Belfast

settlers were to a large extent isolated in their new homes, they never

wholly forgot the land of their forefathers. In song and story, to this

day, one finds constant evidence of the strong spiritual bond uniting the

two islands, and the intense loyalty of the early settlers to the Skye

tradition burns in the breast of the present generation with a flame as

steady as it did in any that has gone before. All are haunted by the same

dreams.

"From the lone shieling of the misty island

Mountains divide us and the waste of seas;

Yet still the blood is strong, the heart is Highland,

And we in dreams behold the Hebrides."

The recent call to battle

met a ready response, and many of the youth of Belfast sleep in "Flanders

Fields" beside their Skye kinsmen, fired by the same purpose, all "brave

sons of Skye." Thus was verified almost two hundred years after, the

character ascribed to these people by the great Pitt (afterwards Earl of

Chatham), in addressing the House of Commons, when he said: "I have sought

for merit wherever it could be found. It is my boast that I was the first

Minister who looked for it, and found it in the mountains of the North. I

called it forth, and drew into your service a hardy and intrepid race of

men; men who, when left by your jealousy, became a prey to the artifices

of your enemies, and had gone nigh to have overturned the State in the war

before last. These men in the last war were brought to combat on your

side; they served with fidelity, as they fought with valour in every

quarter of the globe."

Perhaps no quality

characterized the Scottish race more than their love of education. They

realize, as few other peoples, that knowledge is the sesame that opens

wide the magic door to a life of wider prospect with all the increased

privileges and added sorrows that go with it. Every family strives to give

higher education to at least one son. The parents and other children

patiently undergo all the privations necessary to attain this desired end.

The religious outlook of Scotland, of which their school system is an

expression, has done more, perhaps, than any other agency to inculcate

that proud spirit in the race which encourages the young to feel that

there is no position in society to which the individual may not aspire.

For this reason the Scot is distinguished for his independence,

fearlessness, and self-reliance. As an organizer and administrator he is

imaginative, far-seeing and resourceful. As an empire builder he is

without a superior. In whatever part of the world one may go, wherever the

English language is spoken, one finds in the forefront in every walk of

life descendants of that sturdy stock of pioneers who owe their start in

life to the sound example set before them in youth, of sobriety, industry

and integrity.

It may be expected that the

Selkirk settlers brought with them to their new home this ardent desire

for the better and higher things of life. If they could not have such for

themselves they were all the more anxious that their children should have

what they themselves were denied. During the first few years in the colony

facilities for formal education were of the most meagre kind. Soon,

however, well trained Skye schoolmasters opened up, in private homes,

their little academies of learning, and here the neighboring children

gathered, eager for instruction. The name of the first teacher is not

definitely known, but it is alleged by some that the first school in the

settlement was conducted in a log cabin in the Pinette district by Donald

Nicholson, a Skye man, who arrived on the "Polly" in 1803. Others maintain

it was beside the French cemetery. It was not until 1821 that the

Government prepared to open national schools.

In 1826 a general School

Act was passed. It was re-enacted in 1830. Section four of said Act enacts

that "any person who may be a candidate for the office of master or

teacher in any grammar or district school within this Island shall, on one

of the days of said meetings, or on such other days as any three of the

said Board shall appoint, present himself for and shall submit to an

examination of his qualifications in the following branches of

education-that is to say, candidates for the office of master or teacher

of any district school, in reading the English language, writing,

practical arithmetic and the elements of English grammar; and for the

office of master or teacher of a grammar school in the Latin and Greek

classics usually taught in schools, the elements of English grammar,

reading the English language, writing, arithmetic, practical mathematics

and geography -And if the Board shall be satisfied with the candidate's

proficiency, they shall give him a certificate of his having passed such

examination which certificate shall express the nature of the school for

which the candidate has passed examination."

Prior to 1826 there were no

prescribed subjects of study, but Mr. John Anderson, at present Provincial

Auditor of P.E.I., who was born in Orwell Cove, recalls hearing in

fireside conversation when a young boy, that reading lessons were given

from whatever books were available. Needless to say the Bible and the

Shorter Catechism were used most. The value to the pupil of daily

instruction in the Bible by a man who prized it as a literary masterpiece

no less than as an infallible guide to conduct, was priceless. The ether

subjects, Writing, Spelling, Grammar, Geography, and Arithmetic were no

doubt taught without the aid of textbooks.

In 1823 Rev. John MacLennan

became the incumbent in Belfast. From the day when that noble spirit

arrived in the district until he departed from it, his strength was given

without stint to aid and uplift those among whom he lived and labored. He

soon opened a school at Pinette, and in addition to his many other arduous

and trying duties, he taught there for years. Strange as it may seem,

there were even then, in the humble homes of Belfast, pupils who craved a

knowledge of the classics. Mr. MacLennan taught them Latin in addition to

the ordinary subjects. His work was highly commended by John MacNeill,

Inspector of Schools, in his report to the government, in 1841.

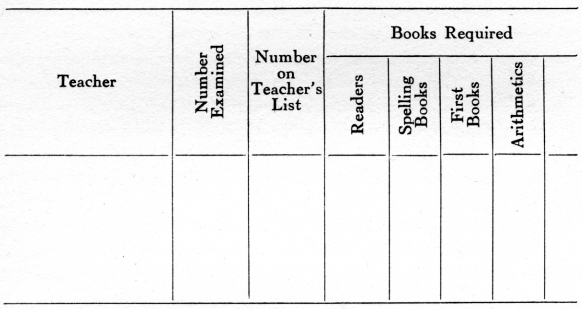

In reporting to the

government in 1838 Mr. MacNeill uses a table which shows the limited

curriculum of that time.

Before two generations had

passed the number of professional men coming from this district proved

that the spirit of their forefathers had taken deep root in the soil of

the new world. Many families contributed members, in some cases as many as

seven, to the learned professions and to business life. No self-denial on

the part of any member of the household was considered too great if

thereby one of the family, who desired it, was enabled to pursue his

studies at a seat of higher learning. Medicine and engineering were looked

upon with great favor, and the career of any youth who entered one of

these professions was watched with eager interest. The Church too was

favored by many, and the early organization of a highly devotional

congregation, presided over by ministers of wide knowledge and broad

sympathy, did much to hold it in the esteem and affection of the people

long after it had begun to lose its power in other parts.

Few congregations of similar size have given as many sons to the active

ministry of the Church. The highly imaginative Highlander, with his love

of meditation, found in the pulpit a fitting medium to express without

reserve, the intensity of the gloomy forebodings which ever characterized

his theory of life and religion.

Owing to the prospect, not

always remote, of political preferment incident to the legal profession,

it was looked upon by many as a most desirable calling. Coupled with this

was the more fixed home life of those following this vocation. Its

vagaries and opportunities for disputation made it congenial to the

peculiar mental constitution of the Highlander, with his alternate periods

of brooding melancholy and infectious gaiety. They were farseeing enough

to recognize the high value of a legal training as a matter of mental

discipline, and the consequent benefits accruing to the student of law in

any calling one might choose. They also realized the great truth expressed

by Edmund Burke, "The law is a science which does more to quicken and

invigorate the understanding than all the other kinds of learning put

together." It is not therefore to be wondered at that, with such an

outlook on life, this district gave a large number of men of high

integrity and skill to the bench and bar.

But the great majority, as

in other parts, were unable to attain a formal higher education. In the

ranks of these, one finds men and women of the highest honor and fidelity,

whose lives have been not only a credit to themselves and a source of

pride to their families, but an honor to their native land. |