|

As summer was almost over

when the settlers landed they erected at once rude cabins to shelter them

from the bitter cold of winter then approaching. These were built of logs

squared and dovetailed at the ends. The spaces between were filled with

moss or clay. The seams were covered with birch bark. Over all a ply of

boards was nailed. The roof was covered with pine shingles. The nails used

in this work were of iron, made by a blacksmith in the settlement. The

windows in these little cabins were few and small as glass was dear. It

took iron courage to face the first winter in this inhospitable climate,

and until the harvest was garnered next autumn their minds were harassed

often by the grim spectre of want hovering about their kitchen door.

Entering the humble cottage

of the early settler one found an abode of Arcadian simplicity. If at meal

time, there might be half a dozen healthy blue-eyed children, with their

parents, seated on planks around the rough board table. The simple fare

consisted of potatoes and pickled herring or dried salt cod. Oatmeal

porridge was the staple breakfast dish. It was many years later before

wheat flour was used daily. In the meantime, barley and buckwheat varied

the oatmeal diet. Many meals were partaken without forks and knives, and

those in use were made generally of horn. The teapot was always on the

hearth. The Scots were inordinately fond of tea and drank copious

quantities of that beverage. As soon as a caller entered the house the

kindly housewife, with unbounded hospitality, proffered a cup.

Of adornments there were

none. The walls and ceilings were of untouched native wood. Later it was

customary to whitewash the whole interior with slaked lime. This sanitary

practice continued until wallpaper was introduced.

The bedstead consisted of a

rough hewn frame on which lay a huge home-made linen tick, filled with

grass, and in later years the choicest oat chaff. This made a warm, clean

and comfortable resting place. At least once a year, at threshing, it was

emptied and refilled. As a supply of chaff for ticks was stored in the

barns they could be changed whenever the housewife so desired.

As domestic geese were

raised in large numbers, feather ticks became common and the guest chamber

was generally equipped with one. The houses were cold. The open chimney,

although healthful, allowed most of the heat to pass off without tempering

the air in the chilly rooms. Beside the fireplace hung the boot-jack,

fashioned from the crotch of birch or maple, while over it rested an old

Queen Anne rifle. Newspapers were unknown. Other books were rare, but the

Gaelic Bible was in every home. By the fitful glow of the pine knot on the

fireplace, the father read the nightly lesson from its sacred pages. All

were warmly clothed. The men wore natural grey homespun, the women drugget.

Their shoes were made in neighboring homes from cowhide tanned in the

settlement. Well rubbed with warm sheep's tallow, they were impervious to

water.

The settlers started at

once cutting down the forest. "How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy

stroke." They reserved all marketable timber to be floated to the

nearest shipping point for export the following summer, or to be converted

into ships. The Scots

and Irish lacked the Englishman's deep appreciation of the beauty of the

forest. In their eagerness to clear the land they swept everything bare,

in many cases leaving neither hedges nor even shelters about their homes.

The English settler, with an eye trained to the beauty of landscape,

frequently brought acorns and shrubbery with him, and today one finds well

laid out grounds that testify to the forethought and taste of these

farseeing English pioneers. The Goff homestead at Woodville, Cardigan, is

an example. Only in the past generation have the Scots made consistent

efforts to beautify their homesteads by planting trees, and laying out

their grounds in an orderly manner.

Not being experienced woodsmen the task of

clearing the forest was very laborious and dangerous, occasionally

resulting in serious injury and even death. But with experience they

gained knowledge, and within a few years the young men became skilled in

all the arts of woodcraft. Lumbering was the chief industry for many

years. The choicest timber was used in shipbuilding. In every harbor along

the coast were built ships, which, manned by daring seamen, brought fame

to their native isle in every leading seaport throughout the world. As

early as 1825 large numbers were launched, and in that year forty vessels

of 8,409 tons were built. The shipwrights' hours of labor were long.

Frequently several miles intervened between the shipyard and the workman's

home. One lady recently told of her father, over seventy years ago,

walking daily, six miles to and from his work at Davies' shipyard. His

honesty, so characteristic of the times, was such that on one occasion,

finding a few iron spikes in his pocket when he got home, he insisted on

bringing them back next day, for, as he said, if he did not do so they

might be in his coffin.

Occasional trees, especially pine, were of

imposing size. On each farm, for many years after the forest was cleared,

isolated stumps stood in the cultivated fields, silent reminders of the

venerable monarchs that once looked down from imposing heights upon the

meaner growth of maple, spruce, birch, beech and fir around them. On one

of these farms, near a grateful spring, stood a notable stump, six feet in

diameter. This remnant of a lordly pine withstood decay for over half a

century. Finally, about 1900, it succumbed to the annual attacks of fire

and axe. Potato sets,

with one eye, were planted in groups of three or four and lightly covered

with the rich soil and ash from the recent fire. After the young plant

showed above the ground it was "killed." As there were no pests (the

Colorado beetle or "potato bug" attacked them first about 1895), and but

few weeds, they were not touched again. They yielded about twenty-fold

next fall. Whent, oats and barley, which were sewn among the stumps

broadcast also gave bountiful yields.

Until the land was stumped all grain was cut

with reaping hooks. When the clearing was large enough, the back-breaking

cradle was used. This instrument consisted of an iron blade or scythe and

cradle with four hardwood fingers, adjusted to the handle. The grain fell

across the fingers. The cradler strove to lay the grain in an even swath

on the highest stubble to lighten the work of the binder, who followed

with a hand rake. While binding the sheaf the harvester rested the handle

on his shoulder. In this spot the skin was soon calloused. It is reported

of one Neil Campbell, of Peel County, Ontario, that he took a swath eleven

feet wide and cut eleven acres in a day. Five acres was considered a good

day's cradling in average grain not broken or tangled. Cutting started

before the grain was ripe. Ripened straw became so brittle in the hot sun

that sometimes it could not be used for bands. In such cases binding was

done in the evening and morning, when the straw was softened by the dew.

Women cut much grain with the sickle, but

rarely with the cradle. "Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield." They

bound, after the cradle, though hampered by their long skirts and often

barefoot. The torture caused by the sharp stubble and prickly thistles,

was almost unbearable.

The reaper, drawn by two or three horses,

displaced the cradle. A man, standing on the machine, raked the grain off

the table. Later a revolving rake, set on a stand, swept the bundle from

the table onto the ground. It could be adjusted so that, instead of every

fourth rake carrying off the grain, the driver tripped it at will and made

the sheaf the size desired.

Those who, under a burning sun, have bound grain infested with Canada

thistle, will vividly recall the hardship of it. Even horny hands did not

escape festering sores. Each year as the seeded acreage increased the

burden grew heavier. Finally the self-binder brought relief from the cruel

task. To the inventor of this useful machine the grain grower will ever

feel grateful. In all

these tasks the women shared equally with the men. They helped to gather

the stumps, and to burn the piles. They bound, stooked, and stacked grain.

They sheared the sheep and washed the wool beside those pleasant little

brooks, that ran through almost every farm. The water used was warmed in

iron boilers brought from Scotland.

For many years threshing was done with the

flail. This instrument consisted of two hardwood bars loosely tied

together at the ends by a thong, preferably of buckskin. The handle was

longer than the swingle to prevent the latter hitting the hand clasping

the handle. Two parallel rows of six sheaves each, were laid on the barn

floor with heads together and bands uncut. These were beaten with the

flail until the straw began to curl. Then they were turned over with the

flail, and the same punishment administered to the other side. The straw

was stored for fodder and bedding. The grain was thrown into the air to

separate it from the chaff. The lightest and cleanest chaff was carefully

preserved to fill the home-made linen ticks on which the hard worked

pioneers spent their all-too-few hours of hard earned rest.

The horse tread-mill consigned the flail to

museum walls. The open cylinders first used were studded with hardwood

teeth. The straw was passed back with hand rakes and forks and stored in

the loft. After the evening meal was over the threshers returned to the

barn. In an atmosphere clogged with dust, they put through the fanners all

grain threshed that day. There seems to have been less opposition to the

introduction of the fanners into Belfast than into Peel County, Ontario,

where a certain lady tried to expel from the church a neighbor who had

brought into the district one of those "wind machines."

Persistent cropping without rotation, soon

impoverished the soil to such an extent that the yield was reduced by

half. To restore fertility, farmers within a radius of several miles

hauled "mussel mud" from Orwell River. This was thrown in small heaps over

the field and in summer scattered in a thin layer. The digger was set up

on the ice over an oyster bed. Those engaged were protected from the

bitter winter winds by spruce trees planted in the ice, about the machine.

An iron shovel worked by horse capstan, was lowered through an opening in

the ice to scoop up and deposit in the sleigh the slimy mass of shells. To

the humble oyster much of the prosperity and consequent happiness of the

Island is due. Among the many resources with which it is so bountifully

blessed this inconspicuous bivalve will ever hold an honored place.

Wooden ploughs with wrought iron mould-board,

share, and colter, were long in use. In the earliest models the share and

mould-board were in one piece. These were later made of cast iron in

separate sections.

Stump fences were never a distinctive feature of Island landscape. Soft

fir and spruce grew in abundance, and as they were easily cut the fences

were made of them. The rails, or "longers" as they were known, were

generally twelve feet long. These fences were built five rails high, then

staked. A rider was placed over the stakes.

The wedding was often a day of jollification.

The men present engaged in feats of physical prowess, running, jumping,

throwing the heavy hammer, shooting at targets, and other Highland games.

It was customary for her parents to tocher the

bride with a milk cow, a few sheep, and bedding for one bed. In the

evening dancing was continued until, with great show and much burlesque,

the assembled guests assisted the newly wedded pair to bed.

As the evening wore to its close a group of

young men from the neighborhood armed with shot guns, tin pans, circular

saws, horns, bugles, and other noise producing instruments, gathered

outside the wedding house for the charivari. Here they kept up a continual

din until, spent with their exertions, they accepted the invitation of the

kindly host to share in the good things on the banquet table, or received

from the groom a gift of money, which, as sometimes happened, they spent

at the nearest tavern before going home.

Dances were usually held in the winter. A

favorite time was at "house warmings," and sometimes at weddings. The

Plain Quadrille, Scotch Reel, Step Dance, and Highland Schottische were

the favorites. Another favorite was Sir Roger De Coverly, also known as

the Virginia Reel.

The musical instrument generally used was the fiddle, gut in default of it

the mouth organ and jews-harp were sometimes used. One talented old lady

with an ear for music, delighted her audience with strains from a

coarse-tooth comb covered with thin paper. She used to be in great demand

at these dances. Much

of the enjoyment at these gatherings was due to the "caller off." He was

responsible for the movement of the various figures, and was often chosen

because of special capacity to provoke merriment. In loud tones heard

above the hum of conversation and the noise of shuffling feet, he called

off the well remembered litany:

Salute your partner -

corner lady -

First four right and left -

Balance four -

Turn partners -

Ladies, chain -

Chain back and half promenade -

Half right and left to place -

It sometimes happened that

the young men and women were present in unequal numbers. The genial

caller-off, or perhaps some wag, to add a note of mirth, often varied the

ritual by calling "swing or cheat." At this some hapless swain quickly

stepped between a dancing lady and her partner and cheated him out of his

swing. This sometimes provoked a jealous suitor to reprisals. On one

occasion an aspiring youth tried to cheat, but for his pains his ears were

boxed soundly by the indignant young lady who would have nothing to do

with him. Mrs.

Alexander Gillis of Kinross, was born on the farm of her father, Donald

Ban Oig MacLeod, beside the Orwell Head church, over eighty years ago.

When recently questioned about amusements in the Orwell district of her

youth, she declared without hesitation that, while geese raffles and other

gatherings provided much fun for the young people, the wauking, or

"thickening frolic" was the happiest day of the year.

These frolics were common in the winter time.

When the web of cloth, containing generally from fifteen to thirty yards,

according to the needs of the family, was ready for thickening word was

sent through the settlement. When those who wished to do so had assembled,

the web, which had been soaking for some time in soap and water, was

"wrung out" by hand. It was then placed on a long table improvised from

boards placed on barrels. The young women lining each side of the table

then grasped the cloth in their hands, at the same time giving a kneading

movement as they advanced along and around it. This was accompanied by a

Gaelic song, the rhythm of which lent itself to the movement. The hilarity

produced by the singing robbed the task of any appearance or sense of

labor. After repeated manipulations the cloth became quite thick. It was

then rolled tightly on a wooden roller and allowed to stand for a few

days. From this it was rolled off onto another roller and allowed to stand

for a short time. When removed it was perfectly smooth and ready to be

tailored by the women or by the community tailor, who was recognized as an

important personage in the district. He went from house to house as his

work called him.

Following the thickening, the evening was spent in step dancing and reels.

When instrumental music was lacking a jigger chanted his wavering melody

to the amusement and great delight of the whole party. Some of these

jiggers had a ready fund of humorous anecdotes and an uncanny gift of

mimicry. They were always welcome guests and did much to improve an

evening. At this

early period the reel and step dance were the only ones she ever saw. Mrs.

Gillis believes that for the first generation the Belfast people never

danced the quadrille. It came into favor later.

The Gaelic songs most often sung around the

thickening table were:

Mo Roighinn s'mo Run

(The Choice of My Heart).

Thainig An Gille Dubh (My Laddie Came to This Town).

Oran Luaigh (Wauking Song).

Songs were composed to

commemorate striking events in the district. Some were in Gaelic, others

in English. One of the most popular of the latter was "The Belfast Riot."

The authorship is in doubt, but it gives a fairly complete history of that

exciting event. It consisted of twelve stanzas. The first two were:-

THE BELFAST RIOT

"Come, brethren all, lend an ear to my story,

And naught but the truth unto you will I tell,

Concerning a fight that's recorded in story,

And of that brave hero who on that day fell.

Yon place in Belfast, with lilt and claymore

The old sons of Scotia in plenty were found,

With thistle and lion and bright banner flying,

And piper's long streamer and pibrochs resound.

"The first of March was the day of election,

And the year forty-seven I heard them all say,

The Irish assembled from every direction,

Each one with his weapon concealed in his sleigh,

To drive from the hustings with cudgel well shapen

All who for brave Donald should vote on that day,

But that day, three to one, they were sadly mistaken

Our noble Scotch heroes made them all run away."

During the long winter evenings young and old

gathered in neighboring homes to "ceilidh," drawn by the genial atmosphere

that pervades certain homes in every community. There they told stories

and sang folk-songs. These were in Gaelic, and among them, according to

Roderick C. MacLeod, the Gaelic scholar of Dundee, the favorites, all

brought from the Homeland, were:

Fhir A' Bhata (O, My

Boatman).

Cabar Feidh (Clan Song of Seaforth Mackenzies).

An Gleann' San Robh Mi'og (The Glen Where I was Young).

Oidhche Mhath Leibh (Good Night-Parting Song).

Posadh Puithir Ian Bhain (Highland Wedding Song).

Horo Mo Nighean Donn Ohoidheach (My Nut-Brown Maiden).

Bu Chaomh Leum Bhi Mirreadh (My Young Brunette).

Bha Mi'n Raoir An Coille Chaoil (Last Night in the Hazel Wood) .

Mo Run Geal Dileas (My Faithful Fair One).

Cumha Mhic Criomain (MacCrimmon's Lament).

Between 1827, when Dr.

Macauley died, and 1840, when Donald Munro, of Alberry Plains, arrived

from Skye, there was no one in the district trained in medicine. During

that period each district had one or more unselfish neighbors of practical

skill, who prescribed simple remedies for the various ailments. Through

their intelligent interest and devoted care many lives were saved, but the

death toll from tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, croup, pneumonia,

and epidemics that frequently swept over the country, was heavy. These men

did valuable work, but the midwives of Belfast exhibited a skill beyond

all praise. They were equal to every emergency. They never turned a deaf

ear to a call for help and without thought of reward they braved miles of

miserable roads and bitter storms. Finally, when they made way for the

modern practitioner, they left behind a record of unselfish care and

skill, rarely, if ever, equalled under similar circumstances.

To every school boy the sea captain is a hero.

In the fall of the year the docks were lined with ships loading cargoes of

the famed McIntyre potatoes, or the equally famed black oats. The summit

of the young boy's desire was gratified if permitted to bring a discarded

whisky bottle full of milk to proffer the captain for the privilege of

inspecting the hidden mysteries of the ocean Leviathan. Returning home,

the assembled family heard of the wonders seen - the captain's cabin with

its reeky lamp, the tiny sweating forecastle, and the cavernous hold in

which was spied the dripping puncheon of Barbadoes molasses, nectar

destined for the children's daily porridge.

These sailors were courageous, stern men.

Inured to hardship and facing danger as their daily lot, they were

disciplined and self controlled. If, in moments of dire peril, the mate's

voice boomed above the fury of the storm, it was not a characteristic of

the sailor. The same man, especially if a Highland Scot, was urbane

ashore, speaking in that quiet undertone that is recognized as a

characteristic peculiar to all sailors, and also one marking the speech of

all the inhabitants of that beloved isle.

For the first sixty or seventy years of the

settlement's existence there were notable fishing grounds stocked with a

plentiful supply of cod, herring and mackerel within a few miles of their

homes. To these grounds the young men used frequently to go for a few

weeks, each summer. Erecting huts on St. Peter's Island they made it their

headquarters, and did a thriving business with American shipowners who

used to buy their catch. Unfortunately, these grounds no longer provide

this near source of pleasure and profit to the people.

Among the few Lowland families who settled

among the Highlanders, and taught them improved methods of farming, were

the Andersons of Orwell Cove, who emigrated from Perth, Scotland, in 1808

to New Perth, P.E.I., and settled in Orwell Cove about 1819. They were,

like most Lowlanders, more thrifty than the Highlanders. About 1842 or

1843 Alexander Anderson II built up-to-date mills on the Newtown River to

which people carried grain from long distances.

The first iron plough in the district was

brought from Scotland by Alexander Anderson I. He also brought the first

cart wheels, and gig, and what did even more for the prosperity of the

community, the famous black oats. All he grew for years was sold to the

neighbors for seed. The daughters in this splendid family were equally as

notable as the sons. Their skill in husbandry and in the domestic arts,

made them outstanding women. The heckle they brought from Scotland, was

the first used in Orwell Cove. They taught their neighboring Highland

women not only how to use it, but also how to plant and harvest the flax

on which to use it.

Another Lowland family of unusual parts was the Irving family of Vernon

River. From the first they exhibited those sterling qualities of thrift,

industry and originality that inspired others and made them leaders in the

district since first they entered it.

THE FIRST MILL IN BELFAST

The mills were among the most important

factors ministering to the comfort of the early settlers. Each favorable

stream had one or more. The first mill in Belfast was built by Lord

Selkirk on the Pinette River near the church. Various parties operated it

until finally, in 1839, John Douse sold it to Alexander Dixon, a miller

from Bowport, Northumberland, England, whose grandson, Joseph Dixon, owns

and operates it today in keeping with the fine tradition handed down

through succeeding generations of that worthy family.

Oatmeal was ground in it for several years

before the first wheat flour was made. In addition to the grist and

saw-mill originally built, both carding and shingle mills were added at an

early date. Prior to the installation of the carding mill, probably by Mr.

Dixon, wool was carded in the settlers homes by small wooden cards studded

with iron bristles. Holding the handle of the card, which was about five

inches by eight inches or ten inches„ in each hand the wool was pulled and

rolled into the required form for spinning.

THE KIRK

The First Church

The Belfast settlers, like their kinsmen of

the Red River Settlement, for many years were without a settled minister.

They regarded this as a heavy cross, but bore it with patience. They

longed to have observed, in the form they loved, the sacred rite of

baptism, of marriage, and the final rites at death. They looked forward

eagerly to the day when, in Gaelic, they might hear in their own church

the voice of their own minister. For this day many waited in vain. At last

in 1823 there was sent to minister to them the much revered John MacLennan.

In the meantime the observance: of religion was not neglected, and nothing

shows more clearly their reverence for the Sabbath than their strict

observance of that day.

The church was the lodestone around which

centred the life of the people. Young and old alike presented themselves

at divine service clothed in their best, and comported themselves in a

manner befitting the sacred nature of the service. There was no endowment,

but all reasonable demands were met. The people contributed willingly of

what they had. The minister's stipend may seem trifling today, but it was

adequate at that time. He was easily able to support himself and family in

a manner befitting his station. No one was rich and it was proper that he

should not have luxuries while his parishioners dined on humble fare.

There was thus complete fellowship in the community.

There is a tradition in Belfast that John

Gillis, a Skye-man who settled in Orwell Cove in 1803, built a log

structure near the French cemetery, probably in 1804, which for years was

used both for church and for school. It is believed that Dr. Aeneas

Macaulay, who had been an army chaplain before studying medicine,

frequently conducted religious service during the early years of the

settlement in that building, and also in private homes.

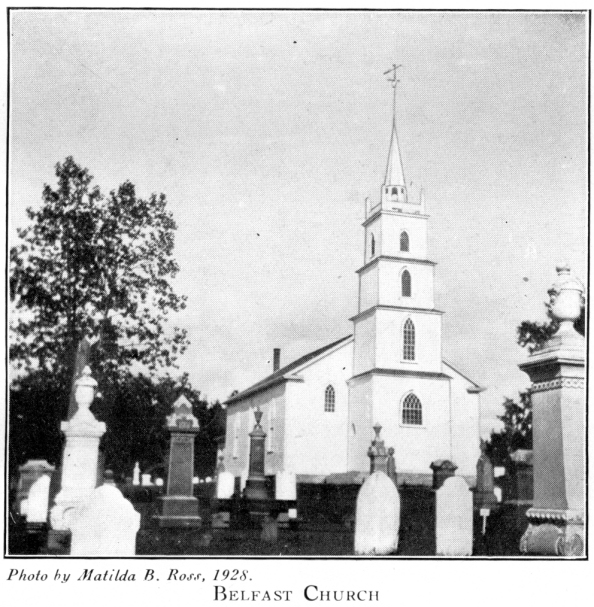

The church records seem to indicate that the

present church was erected in 1823, where it now stands, near Pinette

River, on land granted for the purpose by Selkirk; but it is held by some

that it was built in 1824. It is an imposing and beautiful structure, a

tribute alike to the high value put upon spiritual things by the early

settlers, and to their unbounded confidence in the future of their

settlement. They had early taken firm root in the new land. With the

speedy improvement in their financial condition their contentment grew

apace, and no regrets were felt over their migration from the home of

their forefathers.

The building is sixty feet long by forty-two feet wide. The Wren steeple

is composed of a tower fourteen feet wide by sixteen feet long, surmounted

by a spire of unusual beauty eighty-five feet high. The spire was built by

the two brothers, Neil MacLeod and Malcolm MacLeod (father of Donald Mor

MacLeod of Orwell). They had both worked in the U.S.A., and after

returning to their old home at Murray Harbor Road, about 1860, erected the

spire. There is a gallery on both sides and one end.

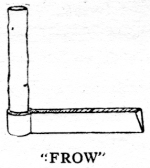

Up

to the time the church was built and for a couple of generations later,

shingles were made by hand from the choicest wood, free from knots. The

instrument used in making them - the "frow" - had a wedge-shaped iron blade

about a foot long attached to which was a short stout handle. The block of

wood was stood on end and the "frow" driven by a wooden mallet into the

end of the block so as to give the shingle, or barrel stave, as the case

might be, the required thickness. With the block braced against the knee,

the handle was then pulled sideways and the required piece split off. The

piece thus severed followed the grain of the wood. Up

to the time the church was built and for a couple of generations later,

shingles were made by hand from the choicest wood, free from knots. The

instrument used in making them - the "frow" - had a wedge-shaped iron blade

about a foot long attached to which was a short stout handle. The block of

wood was stood on end and the "frow" driven by a wooden mallet into the

end of the block so as to give the shingle, or barrel stave, as the case

might be, the required thickness. With the block braced against the knee,

the handle was then pulled sideways and the required piece split off. The

piece thus severed followed the grain of the wood.

This was then planed by hand. The result was a

shingle which endured until completely worn off by the elements. The

shingles now on the churches at Belfast, Orwell and Orwell Head are of

this variety. In the former case, although exposed to the elements for

almost three quarters of a century, they are still sound.

It is not known when the first bell was hung,

but it was cracked in the collapse of the belfry, and sent to England to

be recast. The one now in the tower is inscribed "St. John's Church,

1834." Whether it was paid for by the parishioners or not is uncertain,

but there is a tradition among the older living residents that one of the

early governors had something to do with it. The site is one of surpassing

beauty. On a high hill, surrounded by a grove of beautiful maples, the

church, which has stood for over one hundred years, commands one of the

finest prospects in the whole province. It is a constant reminder to those

who worship in it, of the discernment and discretion of those farseeing

ancestors who chose the spot, so many years ago, and who now, their life

work ended, sleep in hallowed peace in the little graveyard surrounding it

on all sides. Perhaps no church in the whole province has so much of

interesting history and romance enshrined in its annals as the famous old

Belfast church. Ministering to a congregation extending around it to a

distance of five or six miles, it has known over a century of active

prosperity and of inestimable usefulness.

In a copy of the Monthly Record of the Church

of Scotland in Nova Scotia, and the adjoining Provinces, for October, A.D.

1864, in the possession of Miss Bella Macdonald, postmistress, Eldon,

Belfast, appears the following, written no doubt by the minister:

"ST. JOHN'S CHURCH, BELFAST"

"This church, one of the oldest buildings

among our places of worship, is now undergoing a thorough renovation. At a

meeting of the Congregation held a few weeks ago, it was resolved to make

extensive repairs, so as to secure comfort and the respectability of

appearance which should distinguish everywhere the House of God. A large

and very liberal subscription was made on the spot, and although but a few

weeks have passed since the work was resolved on, a large portion of it

has already been accomplished. Before the end of October the whole will be

finished, and it includes, besides other necessary repairs and changes,

the shingling and plastering of the whole building, with the addition of a

large vestry. "This

church, when originally built about forty years ago, was one of the best

of the Protestant churches in the Island. It is now again about to resume

its original position, and to become what the church occupied by a

congregation like that of Belfast should be. In the meantime, and for some

weeks to come, public worship must be held in the open air, which,

although not always very comfortable, is cheerfully submitted to by pastor

and people, from the pleasure and comfort anticipated when again permitted

to occupy the sacred building. To complete these extensive repairs will

require an amount of upwards of £250. A short time ago, another church was

erected at Orwell, for the accommodation of that section of the

congregation residing there, at a cost exceeding £300. This has been done

amid difficulties caused by an almost entire failure in the crops. For two

successive seasons they were subjected to this severe trial, and the debts

then incurred in providing food for themselves and families still continue

to embarrass many of them. The efforts which, in these circumstances, have

thus been made, and the vigour with which especially this last one is

being carried on, speak well for our people, and afford some evidence that

they value the means of grace."

(Signed) A Belfaster.

Following the above article is an account of a

presentation to Rev. Alexander Maclean, the able and highly respected

minister of the Belfast congregation, of a set of silver mounted harness

and whip, gift of a number of gentlemen of the congregation. The address

is reproduced. It is signed by the following committee on behalf of the

donors:

John Macleod,

Elder.

James Nicholson, Elder.

Daniel Fraser, Major.

Donald Macleod.

William Maclean.

Joseph M. Dixon.

George Young, Junior.

The minister's lengthy

reply, dated August 22nd, 1864, is also given.

The Belfast church was thoroughly repaired

again in 1922. Mr. R. E. Macdonald, of Pinette, Secretary-Treasurer of the

congregation, in a letter dated May 21, 1927, reports as follows:

"The first foundation of the Belfast church

was stone blocks, which, after ninety-nine years of service, were, in

1922, as good as new, but not high enough for present needs. We raised the

whole building twenty-eight inches, and replaced the stone blocks with

concrete, enlarged the cellar, built a new vestry, replaced the two small

windows in the east end with one large one, installed two new pipeless

furnaces, shingled one side of roof with cedar, and affixed new eaves to

the main building. Many people considered it impossible to raise this

building, it was done in three hours by forty-eight men, and an equal

number of jack screws and several other helpers. It was a memorable day to

see this beautiful and historic building with its high tower and two large

chimneys raised so easily without crack or break of any kind. The jacks

cost 50 cents each per day, and the men $2.00 per day.

"The total cost of the work was $3,856.01. Of

this sum $3,161.49 was paid out in cash, whilst $694.52 was given in

voluntary labor. "In

the summer of 1926 we painted the whole structure and attached new eaves

on the tower at a cost of about $550.00.

"The cemetery, which was heretofore managed by

a Committee, is now under the control of the Board of Trustees, who are

going to make an effort to maintain the sacred spot in that degree of

respectability pleasing to all who have loved ones interred in it." |