|

It is believed that the

first settlers on the Orwell River were the Macdougalls and John Currie,

all of whom took up land on the north bank. They were soon followed, in

1818, by the Macdonalds from Scotchfort, who had received their grant

several years earlier.

On their way to their new home they blazed a

trail from Head of Vernon River through Uigg to Orwell cross-roads,

thereby establishing the course of the present Uigg road. Others soon

followed, and when in 1821 the whole territory from Orwell bridge to

Kinross was taken up by the MacLeods, Macdonalds and Rosses, the district

had definitely emerged from the forest stage.

The marsh lands along the river were of great

value to the early settler for pasture. Farmers came from miles around and

cut the rank marsh grass with scythes. They built a "stance" on upright

posts above the high water mark, and there they built their stacks. In the

winter, when the marsh was frozen over, they hauled these stacks to their

barns, where it was, for the early years of the settlement, the chief

winter food for their cattle.

Wild geese, ducks, brant, upland plover,

curlews, yellow legs, snipe, sand pipers, and other forms of wild game

birds abounded to an extent that seems incredible today. Sea trout were

also in abundance, as well as other varieties of excellent fish.

Altogether it was a delightful spot.

About the same time Donald Nicholson moved to

Orwell from Orwell Cove, and took up the farm through which the Orwell

River winds for over a mile.

In the primeval forest a clearing was soon

made. Margaret MacLeod (Peggy Neil), recalls the original dwelling house

then built near the river on the north bank. It was a long, low,

comfortable house of several rooms. Between it and the river was planted

an orchard of cherry, plum, and apple trees. Later, in this house, modern

wall-paper was used for the first time in the district, being then a great

curiosity. For many years the family lived on this site. After the milling

business went down a home was built by a son, Peter, to the west of the

road near the site of the present bridge, and beside a spring that still

pours out its cooling waters.

MILLS

About 1830 Donald Nicholson erected the first

grist mill on this stream, near his dwelling house, about three or four

hundred yards above the present Orwell bridge. It was built by William

Harris, a skilled millwright from Devon, England, who later married the

miller's daughter. A dwelling for the assistant miller was also built

nearby. Today there is nothing to mark this scene of early activity, but

the scarred hillside and the remains of the dam built to impound the

waters. This grist mill was operated by him for many years, and for a few

years by his son Peter, by his Highland neighbors commonly called "Patrick

Stenscholl," from the locality in Skye where the family originated. Peter

leased the mill to various tenants until it was finally abandoned.

William Gillis, aged 83, now living at Orwell

bridge, worked in the mill as a young man with Mr. Maclean, a tenant. He

recalls that large quantities of oatmeal were ground there at that time.

The flume was wide enough to permit vehicles

to cross, and for many years it was used as the first public highway

across Orwell River. Later, about 1840, a new bridge was built a few

hundred yards farther down stream at the site of the present Orwell

bridge. A half mile

above this mill was a saw-mill built and operated by George Gay from Lot

49, called by the Highland people "Gaieach Cam," variously interpreted as

reflecting on the physical eye or moral character. He had taken up the

adjoining farm before 1829. His son, John Gay, afterwards occupied the

farm and sold it to John Fletcher, who married Caroline, sister of James

"Yankee" Hayden, of Vernon River. He, about 1840 or 1845, built a grist

mill a few hundred yards farther up the stream. This mill subsequently

passed into the possession of John F. MacLeod of Strathalbyn, brother of

D. J. MacLeod, Superintendent of Education, who added a saw mill and

operated it until a few years before his death in 1915, at seventy years

of age. A son of said

John Fletcher, named James H. Fletcher, whose wife was Miss Moar from New

Perth, after leaving Uigg school attended the Central Academy in

Charlottetown about 1868. In 1869 he was editor of the "Island Argus."

From Charlottetown he moved to Pierre, South Dakota, of which State he was

Lieutenant-Governor from 1889 to 1891. In the Western States he was

recognized as an able orator, lecturer, and newspaper editor. From South

Dakota he moved to Gresham, Oregon, where he lived for several years,

until his death in 191,0, over eighty years of age. His funeral service

was conducted in that town by Rev. Malcolm C. Martin, son of Samuel Martin

of Uigg, one of the neighbors and school companions of his youth.

Owing to economic changes, and the deaths of

the various owners, the lower mills had been abandoned and the dams swept

away, leaving in operation, only the mill highest up the stream. This

continued until about 1910, when it, too, was abandoned and finally swept

away by spring floods.

Some of the stones of the Nicholson mill were

donated by the owner, Peter Nicholson, for use in the imposing Roman

Catholic church then being built in Vernon River. This exhibition of

Christian charity and brotherhood on the part of a neighbor outside the

pale of his church was a source of great satisfaction to the worthy parish

priest, Father James Phalen.

At the noon hour the mill-stream was the

favorite resort of the Uigg school children. There they tied, on

overhanging root or branch, the well-filled flask of precious milk, and,

freed at noon, to it they rushed with headlong speed. The quick lunch

over, along the banks they wandered, in and out among the drooping alders,

eager searchers after hidden mysteries.

The mill-pond was stocked with excellent

trout. In the mind of every Uigg schoolboy of the 80's and 90's is the

picture of the six-foot-two figure of the patriarchal John Roderick

MacLeod, brother of the noted lawyer, Malcolm MacLeod. Each day, about the

end of the noon recess, his tall form might be seen approaching the school

from the north, red beard floating in the breeze and long fishing rod over

his broad shoulder, as he proceeded to his fishing post above the dam. On

their way home from school, the children saw the mighty fisherman poised

on his favorite stump, so far from shore that no one ever understood how

he got there-smoking his pipe, and seeming to enjoy the quiet repose of

that idyllic retreat.

In sharp contrast with this picture of rural

ease was the scene often enacted a little farther down the road, as the

school children passed the mill surmounted by its challenging weathervane.

There the genial owner, covered with flour, provoked beyond endurance by

the patter of stones raining on the roof, was often compelled to rush from

his work to drive off the mischievous school boys then competing to

dethrone the saucy rooster that stood bravely defiant in the breeze.

This beautiful stream was at all times a

favorite resort for those who loved the outdoor life, but particularly in

summer time. The shady forest overhead, with here and there a spring of

purest water issuing from the sandstone rock; the tipping sand piper,

timorous crane, and occasional duck; the eager search under log or

overhanging bank for the elusive and delectable sea trout, which at spring

tides never failed to come, all added a charm and fascination to life that

lifted the ardent dreams of youth from doubtful speculation to satisfied

reality. While

wandering with rod and gun along this stream many a lesson was learned in

hunting and fishing from a parent skilled in both.

Later, along these same haunting banks a

youthful attraction ripened into unbroken friendship with those two genial

and unfailing friends, John G. and William Matheson Macphail, whom The

Ettrick Shepherd might well have had in mind when he wrote:

Where the pools are

bright and deep,

Where the grey trout lies asleep,

Up the river and o'er the lea,

That's the way for Billy and me.

Where the blackbird sings the latest,

Where the hawthorn blooms the sweetest,

Where the nestlings chirp and flee,

That's the way for Billy and me.

Where the mowers mow

the cleanest,

Where the hay lies thick and greenest,

There to track the homeward bee,

That's the way for Billy and me.

Where the hazel bank is steepest,

Where the shadows fall the deepest,

Where the clustering nuts fall free,

That's the way for Billy and me.

Each season had its own

peculiar diversion for the young schoolboy. Fall and winter being the

hunting season for fur bearing animals, the play of human wit against

animal cunning added great zest to those dark and dreary days. The Orwell

River always harbored a few mink. The simple box trap, baited with a

freshly caught trout, first dragged along the ground to the trap, led many

unwary animals to their doom. Their pelts generally sold for three dollars

each, and, where tastes were simple and wants few, the prize was

sufficient to give each member of the household a little token of the

youthful hunter's affection.

Usually at least a dozen trips were made for

each time the trap was sprung. When so found there instantly arose before

the eye the image of a pelt, of size so great, and sheen so rare, that

already in schoolboy fancy much of the fantastic price realized was spent

in additions to the indulgent mother's and beloved sister's all too meagre

wardrobe. But sometimes the quickly formed dreams of youth came to an

equally sudden end. From the momentary, if high, pedestal of delight, the

fall was crushing when, on cautiously peering through the partly opened

door, there was descried two glistening terror-stricken eyes. What could

it be? Surely no mink had eyes like these. With trembling hand the door

was opened wider yet. Then, and not till then, did the friendly meow

issuing from the dark recesses of that evil house dispel all fear, and

reveal a marauding neighbor cat. The disappointment was only surpassed

when, on a subsequent occasion, the same animal was convicted of a

similar, but final, offence.

The joy at capturing a mink was measured to a

certain extent by the price received for its pelt. In the case of the

captured fox it was different. The thrill experienced by one who for days

and weeks has matched his wit, and won, against the craft and cunning of

the red fox cannot be imagined. The woods at the back of the old farm

extended for several miles in an unbroken crescent from Orwell North to

Uigg and Dundee. This stretch of heavy woods harbored many of the most

cunning members of the fox family. They preyed on the neighbors poultry

and were outlawed by everyone. Those who were not interested in the chase

looked upon those who captured them as public benefactors. Fox pelts, if

taken in season, were generally sold for about five dollars each. On one

occasion an eager hunter was following hard on one of these raiders when

the track led into a hollow tree lying on the ground. Immediately blocking

one end of the log with his coat, he filled the other end with snow.

Cutting a hole in the centre Reynard was soon a prisoner. Nor was the joy

confined to the human family. There was much competition for the privilege

of gun bearer on these expeditions. The moment the chosen one sprang on

the table to reach the old gun, Husk was seen to tremble and his sleepy

eyes to open. When the outstretched arm had seized the gun his quivering

form and frenzied bark argued trouble for the nimble red squirrel and

fleet rabbit, game in which the woods abounded.

The Nicholson home was a noted stopping place.

The genial host and hostess made everyone welcome. Among those who

frequently slept under its hospitable roof was George Munro Grant, later

the illustrious Principal of Queen's University, then a missionary in

Alberry Plains and adjoining districts.

Angus A. MacLean, K.C., ex-M.P., of Charlottetown, recently told of how as

a little boy he used to see Peter Nicholson, elder, in his pew in church

every Sunday, rain or shine. Six miles of miserable roads had no terrors

for these early churchmen. He recalls also that Mr. Edward Robinson, of

Newtown, came to church with the first wagon (as the buggy was then

called) in the district. Peter Nicholson had the second. Up to that time

people either walked, or drove in carts or gigs. After the introduction of

this new type of vehicle few, if any, had the moral courage to use the

farm dump cart or two-wheeled truck on Sunday. Their proud Highland nature

would not admit poverty, and rather than have their possessions seem mean

by comparison they walked.

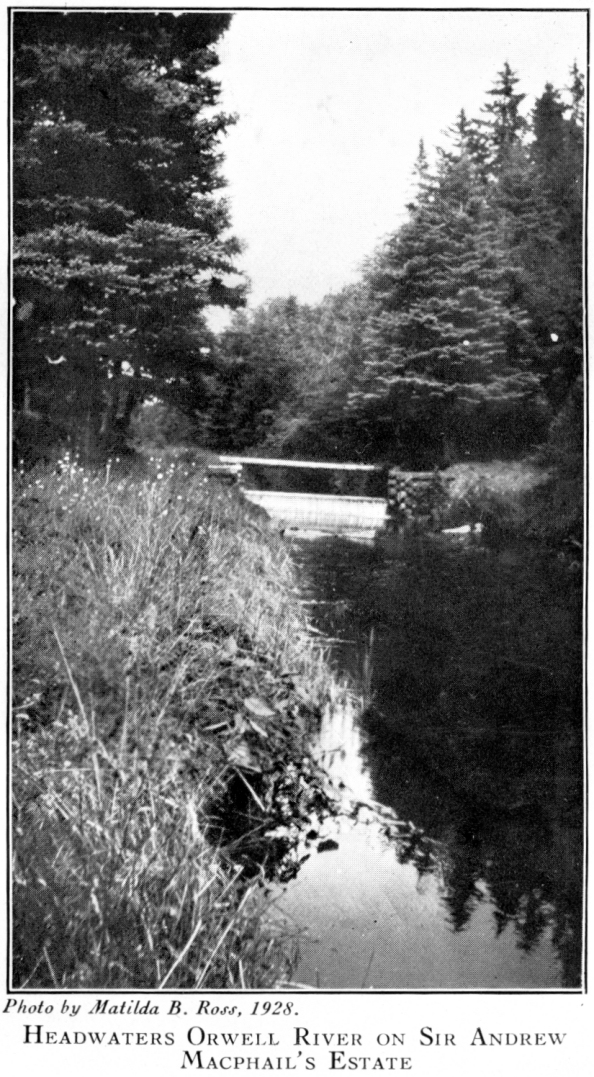

Beloved by all for his genial good nature,

Peter Nicholson left this charming estate of 250 acres to his widow,

Marion Munro, and three daughters. Marching for over a mile along both

banks of the river from the Murray Harbor road westerly towards the sea,

this tract of land was then, as it is today, a spot unsurpassed for quiet

natural beauty. A few years ago it was purchased by Sir Andrew Macphail,

who, using it as a summer retreat, indulges his poetic fancy along its

shady banks in pursuit of the delectable sea trout for which, from time

immemorial, it has ever been famed.

La Grande Ascension was the' name of the

abandoned French settlement of about eighteen families, near the mouth of

Orwell river. The Scottish settlers corrupted this into Sentie or Sengie.

On the point was a shipyard owned by Benjamin Davies of Charlottetown, a

Welsh shipowner, who there built many barques, brigs and smaller craft.

Around this shipyard, as a boy, played his son Louis, who later, as Sir

Louis Henry Davies, was for many years Chief Justice of Canada. He was

born in 1845. His interest in the scenes of his boyhood escapades never

abated, and a few years before his death in 1924, on his annual summer

visit to Orwell, which he had not missed in forty years, he recalled with

great amusement an occasion when his brother, in a fit of youthful rage,

foiled in his attempt to catch him, threw a hatchet at his head. Had the

missile found its mark Canada might have lost the services of a gentleman

who, throughout his whole career, gave the best efforts of which he was

capable to the public service of his country. He was always distinguished

for his gracious manner, polished speech, and loyalty to friendships.

These qualities contributed greatly to advance his career.

Farther up the river at the mouth of Currie's

Creek as late as the early sixties John MacQueen and Donald Shaw built a

schooner, and within the memory of several now living Donald "Stonehouse"

MacLeod, of Orwell, launched several schooners and brigs on the shore of

the Stewart farm at Orwell bridge, where schoolboys now wade across the

stream. These ships were built for sale. Many of them were loaded with the

famed black oats or with potatoes, and sold with their cargoes to English

and American investors.

Since those days the rivers have diminished in

volume. The snows which formerly lay deep in the woods fed the streams for

months, whereas today it is carried off by warm winds in a few hours,

sweeping away bridges and mill dams in its mad course to the open sea.

ORWELL SCHOOL

The first school in the Orwell district was

built of logs about 1825. It stood on the south side of the river, a few

hundred yards below the site of the present bridge.

The first teacher in it may have been Samuel

Martin, from Orwell Cove, or Donald Graham. The teacher boarded for a week

at a time in each family, going through the settlement in this way. In

1839 or 1840 it is known that William Ross, from Pictou, N.S., was

teaching in the log school on Murdoch McLeod's farm, a little west of

Orwell cross-roads. This school site was later abandoned for the present

site of the church at Orwell cross-roads. This was about 1850. The first

teacher in the school at this location was Alexander Maclean, who was born

in 1831, and had attended the old log school while living with his sister

Catherine, wife of John McQueen, in Orwell North. He was later graduated

in Medicine from McGill University, and practiced in Montague. The second

teacher in this school was probably Allan McDougall.

After a few years this building was moved to a

point in Orwell North, on the farm later owned by Alexander MacKinnon.

The first teacher in this location was John

Brooks from Murray Harbor, who taught in the years 1855 and 1856. The next

building was of frame construction, on the same site.

When the boundaries of the Vernon River and

Orwell districts were rearranged, the school site was again changed back

to Orwell cross-roads, and here in 1895 a new one-room frame building was

erected where it now stands, on the south-east corner opposite the Orwell

church, where an earlier one had been built half a century before.

About 1850, when some of the oldest residents

now living in the district attended school, the subjects taught were,

Reading in English, Arithmetic, Geography, Spelling and Writing. No

instruction was given in History.

When Mrs. Alexander Gillis, now living at

Kinross, went to the Back Settlement (Lyndale) school about seventy years

ago the master was Ewen Lamont, a worthy member of a talented family. The

above subjects were the only ones taught then. The master lined the copy

books in Gaelic, and also in an English translation of the Gaelic.

Each morning the New Testament was read, and

one short period each week was spent on the Shorter Catechism, and on the

rudiments of singing.

Mrs. Norman Samuel MacLeod of Uigg, now

ninety-two years of age, recalls that in her youth the New Testament was

the Reader used in the school she attended.

FOUNDING OF CHURCHES

At Orwell and Murray Harbour

Road The population

of Orwell had increased so much that the Presbyterians in that district

decided to build a church at Orwell cross-roads on land donated to them by

Peter Nicholson. Accordingly, in 1861, they erected the frame building

which stands today. It was forty feet long by twenty-six feet wide,

plastered throughout. The tower was ten and one-half feet square. It was

surmounted by a low spire, on which stood a weather vane, unadorned by

crowing cock. The parishioners supplied all the material, and most of the

labor, free. In August, 1891, a frame structure twenty by forty feet was

added. One-third the cost was paid by that good citizen, Alexander

MacLeod, commonly called the Old Captain. The builder was Donald Martin of

Uigg, brother of Martin Martin, Grandview, who built the first church.

For the first few years after the church was

built, until permanent seats were installed, the congregation sat on

planks placed for seats. Whatever these planks may have been they could

not be more uncomfortable than the narrow straight-backed seats that were

substituted for them. But this was not all. The painter, whoever he was,

so mixed his materials that the worshippers stuck fast to the seat.

Especially embarrassing was it for the ladies, who never knew whether

their more delicate apparel would remain on themselves or adhere to the

seat. Margaret Neil

MacLeod recalls, but cannot say that it was at the formal opening of the

church, that the minister, Rev. Alexander Maclean, called on her brother

James to lead the singing. He demurred. Mr. Maclean urged him, saying "It

will be easier next time." The pastor's importunity prevailed and Mr.

MacLeod led, and for some time thereafter was "precentor" in that church.

The writer recalls a few occasions in youth,

watching with admiring eye, this same gentleman (then an aged man) feeling

for the note, when yielding to the call of necessity he filled the absent

precentor's place. If, late in life, Mr. MacLeod opposed the introduction

of an organ into the same church, it was with the same gentle urbanity

that ever characterized his life and marked him as one of nature's

gentlemen. Beloved by all who knew him Mr. MacLeod passed to his reward

two or three years ago, at ninety-two years of age.

The Orwell church was known to some as

"Findlay's" church. Robert Findlay preached there occasionally. The

Belfast minister used to conduct services in the church on every third

Sunday. The Church Minute Book of 1872 occasionally mentions "Sermon read

today." Mr. Findlay, on the occasions referred to, read a sermon and

expounded the Scripture, sometimes to the amusement of the bashful, if

irreverent, youths who clung to the back seats near the door, where they

might not be denied the soporific pleasure of their favorite nicotine.

In the Minute Book of the congregation for

1872 Hugh Findlay is described as secretary of the Orwell section of the

Belfast congregation.

The list of ratepayers with amounts agreed to

be paid is set out. The first half dozen are as follows:

Peter Nicholson £1 0 0

Capt. A. McLeod 12s 6

Mal. & John McQueen 6s 3

John McLeod (Sentie) 7s 6

John McQueen 12s 6

Angus McQueen 12s 6

The first interment in the Orwell churchyard was that of Dr. Archibald

McLeod, son of the Old Captain, in October, 1884.

A few years subsequent to 1829 the followers

of Rev. Donald McDonald erected a log church at Murray Harbor Road, now

known as Orwell Head. About 1840 or 1842 this building was replaced on the

same site by a large frame structure, plastered within. There was no

tower. It was later found inadequate to accommodate the vast throngs that

gathered there to hear their beloved pastor, so the building was sold to

Duncan McDonald, son of Findlay, the minister's brother, who lived and

died, unmarried, on the farm beside the church, formerly occupied by Murdo

McKenzie, the schoolmaster. The said building is now used as a barn on

said farm. In or

about 1864 the present imposing, but inartistic, frame church, was erected

where the last one stood. It is sixty-two feet long by forty-two feet

wide, with tall tower and taller spire, which was built on the ground and

hoisted to position on the tower. There is a gallery at both ends and at

one side. Although a

few members remained out, this congregation was received into the

Presbyterian Church in Canada on July 7, 1886.

The minister's stipend for the first year was

$600.00. At the

annual meeting held on December 12th, 1891, it was decided to buy an

organ. This was installed in the church in the following spring, but not

without opposition. At this time John S. Martin, later Speaker of the

local legislature, was official precentor.

At the annual meeting held on December 12th,

1892, a letter was read from a member asking the meeting to vote the

Presbyterian Hymnal into the church, but so great was the opposition that

a vote was not taken. A year or two later it was introduced without

opposition. In June,

1928, the Orwell section of the congregation united with the Methodist

churches at Vernon River and Cherry Valley, and the Orwell Head section

united with the Valleyfield congregation, both in the United Church of

Canada. The following

is a list of ministers of the Orwell Congregation:

Donald Ban McLeod (M.A. Park, Mo.; Lane Theo.

Sem.) July 28, 1887, to April 11, 1899.

Alexander J. MacNeill (B.A. Queen's), November 21, 1899, to January 27,

1906; born in Whycogamah, Cape Breton.

H. M. Michael (Glas. Univ.) December 23, 1906, to September 15, 1907; born

in Scotland.

Donald Ban McLeod (M.A. Park; Lane), June 20, 1908 to November 2, 1913.

W. H. MacEwen (Dal. B.A. Omaha Univ.; D.D. Buena Vista, Iowa), October 1,

1914, to March 25, 1923. Born in St. Peters, P.E.I.

G. A. Grant (M.A. Dal.; B.D. Pine Hill), April 2, 1924, to June 1, 1928;

born in Pictou Co., N.S.

Henry Pierce (B.A. Mt. Allison) October, 1928; born in Winsloe, P.E.I.

Donald Macdonald, Thomas Boston Munro, Malcolm

MacLeod, and their respective families, left Murray Harbor Road in 1874,

and settled in Schuyler, Kansas. Here they took up land and became

valuable citizens in inculcating a respect for law and order, and in

exercising a restraining influence on the turbulent spirit then dominating

the opening of that State. Among the flood of immigrants then pouring into

Nebraska, they played an honorable part, and many churches and schools in

that state are living monuments to the unselfish labor, timely interest,

and zeal of the two well educated Skye men, Donald MacDonald and Thomas

Boston Munro, and of their respective wives and families.

One of the nine sons of said Malcolm MacLeod

was Donald Ban, who later returned to Orwell and was minister of united

Orwell and Orwell Head congregation from 1887 to 1899.

He was graduated M.A. from Park College,

Missouri, in 1881, and in 1883 from Lane Theological Seminary, Cincinnati,

first honor man of his class. The same year he married Miss Stella Dyer,

of Columbia, Missouri, a charming Southern lady. Their daughter,

Elizabeth, is wife of Rev. William C. Wauchope, now of Buford, Georgia.

His first charge was at Nortonville, Kansas.

From there he moved to Water Street Presbyterian church, Quincy,

Massachusetts, and while there in 1886 his devoted and much beloved wife

died. From 1887 to 1899 he was minister of the Orwell congregation: from

1899 to 1903 of Zion church, Charlottetown; from 1903 to 1908 of Union

Square church, Somerville, Massachusetts, and again from 1908 to 1913

minister in Orwell. From 1913 to 1915 he was back in Quincy,

Massachusetts, and from 1915 to 1918 he was pastor of his last

charge-Upper Stewiacke, Nova Scotia-when failing health compelled him to

retire from active work.

He started for Orwell, the place he loved so

well, but his strength declined so rapidly that he was unable to continue

the journey, and on May 23, 1918, while in Charlottetown, he passed away

before he could reach the beloved district where he spent so many years of

unselfish and devoted labor. Few clergymen have held the affection and

esteem of their congregation in as high degree as did Mr. MacLeod. His

influence on the youth of the community for a generation was profound.

Urbane and cultured, he was at all times the most agreeable of companions.

To Youth he was a companion, to Age a mentor. A man of broad tolerance,

not too censorious of human frailties, he was not of that narrow and all

too common class of churchmen who "attack prevailing fashions without any

sense of proportion, treating follies on the same footing as scandalous

vices." A bronze

tablet on the wall of the Orwell church, records the death in the Great

War of the following members of the community:

1. Pte. ANGUS MACLEOD,

Winnipeg Mounted Rifles,

born Feb. 20, 1875, died Sept. 15, 1916.

2. Lieut. ANGUS NICHOLSON,

16th Canadian Scottish,

born Feb. 13, 1895, died March 5, 1918.

3. Sergt. HAROLD MACPHEE,

105th Battalion,

born April 5, 1895, died Sept. 29, 1918.

4. Pte. JOHN MACLEOD,

20th Engineers U.S.A.

born Aug. 1, 1894, died Nov. 9, 1918.

The following Gaelic message from Rev. John

MacLeod, a Scottish minister, was carried to the elders at Orwell by

Annabella, widow of Dr. James Munro of Kilmuir, Skye, in 1840:

A few lines to the church.

Tha lain MacLeoid bhur brathair agus bhur

cosheirbhaisach anns an tighearn, a cur beanachd a chum na seanair agus

na'm braithrean dilis ann a'n Griosda ann a'm Braith Orwell, agus a

dh'ionnsuidh nan uille thaag aideachadh ainm Iosa a guidhe gu durachdach

aig caihear na'n Ghras, gu'm biodh an t-iomlan dhin air bhur gleidhadh gu

tearuinte trid air turai Tre an t-shoaghal thrioblaideach so.

Oir ged nach h-urrain sibhse mo ghuth a

chluinntean tha Neach eile ann a tha cluinntean ar 'n uirnuighean uille.

Air an Aohbar sin that miag' iaridh bhur 'n

uirnuighean air bhur sonninne anns an site so.

You will present this among the Elders.

A few lines to the church.

John MacLeod, your Brother and co-worker in

the Lord, sends a blessing to the Elders and the Faithful Brethren in

Christ in the Parish of Orwell, and to all who acknowledge the name of

Jesus, and earnestly prays at the throne of Grace that all of us be kept

safely during our journey through this troublesome world.

Though it is not possible for you to hear my

voice there is Another who hears all our prayers, and for that reason I

beseech your prayers for us who are living in this place.

You will present this among the Elders.

Margaret McLeod, daughter of Neil McLeod, of

Orwell Bridge, when recently interviewed in Orwell spoke with eager

interest of the early history of the settlement. Peggy Neil, as she is

familiarly and affectionately known to the whole countryside, is possessed

of a keen eye and a memory that would mark one with distinction at any age

in life. Eighty-seven years spent wholly within the confines of her native

Orwell have made her mind a repository from which those seeking to unravel

the devious intricacies of family relationships, and local history, may

dip but never sound the depths. The minutest details of the public and

private life of the people are at her finger tips to give or withhold

according as her wise discretion or fancy dictates. No one could be more

willing to give than she, of this valuable store of knowledge, to those

whose interest or pleasure it is to hand down to future generations an

accurate record of the community as it was seen and understood by her.

"I recall," said Miss MacLeod, when recently

seen at her home, "many of the original settlers. A more honest, upright,

God-fearing people it would be hard to find. They all conversed in Gaelic,

but most of even the original settlers later acquired English as well.

"Although times were hard our wants were few

and simple, and I do not recall that we had to deny ourselves more than we

do today. It may be that not knowing luxuries we never craved them. The

only pleasures women engaged in were the 'ceilidhs,' which I suppose

correspond to the modern `teas.' The neighboring men and women gathered at

each other's homes. The Highlanders were all fond of singing and music.

The flute, fiddle and mouth organ were the usual musical instruments.

There was always someone with an ear for music. At these 'ceilidhs' tales

of witches and ghosts were told so vividly that we were often afraid to go

home in the dark. Many of the women used snuff and some smoked the pipe.

People were hospitable and one could always count on a warm welcome in

every home. The church was the great meeting place, where old friends saw

each other on Sunday. In spite of all the comforts of the present age I do

not look back on the period of my youth as a too severe one, even if women

did work more in the the open field than they do today."

Few, if any, of the old timers now living in

Orwell have minds so stored with the history of past events in Belfast as

Margaret Macqueen, who is now approaching eighty-four years of age. Her

mother was a notable woman in her day. Born in Uig, Skye, in 1819, she

emigrated to Prince Edward Island in 1829.

At Montague River, in 1839, she married John Macqueen of Orwell. At that

time the roads were simply a "blaze" through the forest. It was regarded

as no hardship that the eight or nine mile drive from Montague River to

their new home in Orwell North was made on horseback, bride and groom

riding on the back of the same animal. This delightful old lady lived to

be almost ninety-six years of age, passing away in 1915, with faculties

unimpaired to the end. Though she was almost a centenarian she never

conversed except in Gaelic. But in Belfast this was not unusual. In 1915

she was sprightly, cheerful, and fond of life; her kindly, lovable nature

bursting forth in her favorite expression "Oh, mo ghaol, mo ghaol" (my

dear).

"But," said Miss Macqueen,

when recently talking about these events, "this drive was not considered

any hardship. I recall myself as a young girl walking to Charlottetown and

back the same day. This journey meant going up to the Head of Vernon

River, for there was then no bridge at what was later called Vernon River

Bridge. Many neighboring women did likewise. Among them I recall two of

the most remarkable ladies whom I ever met. Rachel Gordon of Uigg, wife of

John MacLeod, who lived to be almost ninety-eight, was one. The other was

Miss Gunn from Miramichi, wife of his brother, Big Murdoch MacLeod. She

lived for a century, all but three months, and up to her death a few years

ago enjoyed perfect health. She thought nothing of starting on foot to

Charlottetown, even at middle age, with shopping basket over her arm. She

always completed the forty mile trip the same day in time to prepare the

evening meal for her family.

"On these journeys along the Town Road we

frequently met the New Perth and other settlers living along that road.

They used a mode of conveyance that we never saw in use elsewhere. They

called it a `sliding car.' This device was made of two poles fastened to

the hames with the rear ends on the ground. Across these poles were

fastened boards, on which the kindly father carried over the weary twenty

mile trail from town, to his anxiously waiting family, the meagre supply

of provisions necessary to meet the simple demands of the frugal lives

they lived. "In our

district, in those early days, produce was generally carried in huge home

made linen sacks thrown across the horse's back. Grain was often taken in

open row boats to Acorn's grist mill near Pownal. We often cut our grain

at night. Young men and women gathered in crowds and worked with reaping

hooks in the small fields surrounded by woods. Lit up by flaming birchbark

torches on the end of long poles, the scene was an animating one. Many of

the settlers made notable cheese. They cured it in grain stacks. This

treatment gave a distinctive flavor greatly relished by those who partook

of it. "Although

times were hard there were but few beggars. As there were no public

institutions for the weak-minded, they wandered about the country, a

constant source of anxiety to others. Everyone was busy. There was no

reason or excuse for idleness when even the women and children could be

usefully employed gathering slash from the cut-over land, when seasonal

work failed. Only the wilfully idle had an easy time.

"Social conventions assumed a more important

part in the life of the district as wealth increased. When the famous

Highland minister, Roderick MacLeod (known as Maighstir Ruairidh), then

visiting at the Nicholson home in Orwell, came down to breakfast in bare

feet, the daughters of the house were so surprised at the strange sight

that they ever recalled it with amusement.

"The early settlers had few holidays.

Christmas passed unnoticed. New Year's Day was the great day of the year.

On the Eve of that day `striking parties,' composed of young folk of the

district, armed with sticks, marched through the settlement. When they

arrived at a house they surrounded it, and to the accompaniment of music

from the sticks beating the log walls, vigorously sang a Gaelic refrain,

which may be translated:

Get up auld wife, and

shake your feathers,

Dinna think that we are beggars,

We're jist bairns come oot to play,

Get up and gie us oor hogmanay.

"If, as happened but

rarely, there was no 'Scotch' on hand, they were given cakes. But these

were poor substitutes for what they sought, and the eager haste with which

they directed their fleet footsteps to the light beckoning from the

nearest neighbors' window, revealed an intention to ignore substitutes,

and an anxiety to slake their inherited thirst by the only means known to

them and to their forefathers for generations. When the log houses were

replaced by shingled ones, these parties were discouraged and finally

abandoned. "There was

no market for farm produce. The result was that laborers were paid paltry

wages, as the following entry in an old Minute Book will show: 'Dec.

20/61. Norman McPherson began working with John McQueen for three years to

serve at rate £2 for first year, £2 4s. for second year and £4 for third,

and if proves well gets £6 for third year.'

"We were as content with our lot then as we

are today. We denied ourselves what we knew we could not afford. This was

an excellent training, and did much to build in the poor but proud

Highlander a character marked by integrity and honor, virtues that he

prized above life itself." |