|

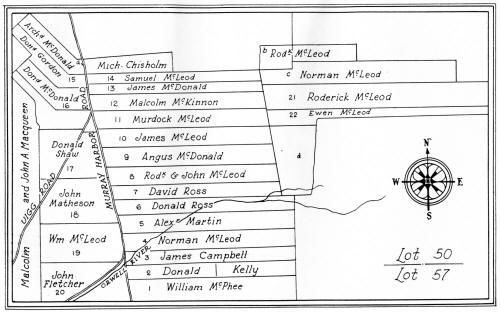

Argosy never sailed with

more precious cargo than that discharged at Charlottetown on June 1st,

1829, from the good ship "Mary Kennedy." There were eighty-four heads of

families in the party. They settled along the Murray Harbor Road, and in

the Back Settlement, later called Lyndale. Each family bought from fifty

to one hundred acres of land. They named the Uigg district after their

birthplace, Uig, in Skye, famed for romantic beauty, and deriving its name

from the Norwegians who held the Western Islands of Scotland for

generations.

The road from Vernon River

to Murray Harbor had been opened shortly before the Uigg settlers arrived.

In that whole stretch of territory there were then only three residents.

One of them was Murdoch Mackenzie, a native of Inverness, who arrived in

Belfast in 1821, accompanied by his wife Mary Mackinnon, and his father

John Mackenzie. In 1822 he took up the farm on which now stands the Orwell

Head church. He died in 1885, aged 100, leaving several children

surviving.

The 1829 settlers found him

dwelling in a log cabin, in the heart of the forest, with only a small

patch of clearing about him. If life was simple and the world's luxuries

few Murdoch Mackenzie had a fine mind. He opened a school in his little

log cabin, and there devoted himself to the improvement of the minds of

the sons and daughters of his near neighbors, who sent their children to

the kindly Scottish schoolmaster to receive at his hands the solid

groundwork of a liberal education.

After the morning lessons

were heard this excellent teacher allotted his pupils their daily tasks.

It was then his habit, on occasions, to seek repose on a bench beside the

wall. Here he lay until gnawing hunger announced to the children the near

approach of noon. All work was then laid aside; a great tumult was created

until finally the master's form was seen to move. Rubbing his weary eyes

he arose, and walked outside. There he gave one fleeting glance at the

declining sun and returned to announce recess.

Later, when the country was

settled farther south, Mr. Mackenzie opened a school in the Grandview

district. Here he taught for many years.

Among the pupils inspired

by Mr. Mackenzie with a love for education was Donald MacLeod, son of

Donald Ban Oig MacLeod, who lived next door to the master. At an early age

he moved to Parkhill, Ontario. His daughter, Katelena, recently told of

her father's practice, continued till old age, of taking a Greek or Latin

Bible to church, and following the reading of the Book in those languages,

both of which he had mastered.

Rev. Donald Macdonald said

of this noble man, that he was the only person in the whole countryside

who possessed a knowledge of Greek. One of his daughters married Alexander

(Garf) Macpherson, of Lyndale, and their descendants still reside in the

district.

Perhaps in the history of

the migration of the race no more highminded and worthy people ever

entered a new land than those who came out on the "Mary Kennedy." Their

heritage of piety persisted undiminished for several generations in their

new home. Like their forebears they were rigid Calvinists. The atmosphere

of the district, like that of all Scottish districts of that age, was

rather sombre. A small group, the Macdonalds, MacLeods, Gordons, Munros

and a few others, were Baptists, who, for conscience sake, had withdrawn

from the Presbyterian Church. Among them was a man of outstanding

personality. Rev. Samuel MacLeod was born at Uig, in the Isle of Skye in

1796, and died at Uigg, P.E.I., in 1881, where he was buried in the

Baptist churchyard. Over the destinies of this church for many years he

presided, with inspiration not only beneficial to those who heard his

earnest message, but also with benefit to that much greater multitude,

who, through the continuing power of precept, and example, are unconscious

heirs of the atmosphere of truth and rectitude that has continued long

years after its inspirer has left the scene of these, his earthly

triumphs.

So far-reaching was the

influence of this small Baptist group in Uigg, that neighbors of other

denominations testify that throughout their lives they have held the

Baptist Church in especial veneration and reverence owing to the

irreproachable lives and blameless character of this small group in Uigg

assembled about their kinsmen and beloved pastor, the Rev. Samuel MacLeod.

If a reason is sought for

the great success and high position attained by so many poor Highlanders,

not only in their own country, but also in lands across the seas,

particularly in India and in Canada, it may be found in their sound

education, and in that poverty, which inured them, from youth, to self

denial. Early in life individual effort was demanded, and the valuable

lesson was soon learned that it matters little what is earned if all is

spent. The man who practises self denial and sets apart a portion of his

earnings to accumulate and work for him in fair weather and foul, is the

man who, in the end, attains wealth with its attendant power, and better

still, character.

The forming of definite

habits of self discipline and control is the guiding star that moulds the

character and directs it into definite channels of self respect,

independence, and integrity. Rarely is a person, who follows this line of

conduct, found committing an unworthy action. The Uigg settlers, in

striking degree, exemplify the fundamental soundness of this theory of

life.

Rev. Donald Gordon

Macdonald, of Vancouver, recently spoke as follows: "I was born beside

Rev. Samuel MacLeod. To say that he was a man of outstanding natural

'ability is no exaggeration. His learning and wisdom were profound; his

character irreproachable; his influence widespread; his example wholesome

and contagious. In all my experience of eighty-six years of life, I look

back upon the character of Rev. Samuel MacLeod as one of the most potent

and signficant things I have met. In speaking of him less than justice

would be done were I to refrain from paying, in my own declining years, a

final tribute to the memory of a group-the small Uigg group-of MacLeods,

Gordons and Macdonalds, who constituted in themselves perhaps the highest

expressions of the human family that it has been my privilege to know.

When one reflects on the disregard for the rights of others so common in

many ranks of society, the record of the Uigg district does much to

restore confidence in human nature. Perhaps in no other place has there

been a more willingly admitted regard for the rights of others. They

seemed to recognize the great truth at the basis of the whole social

structure, that the law is a great man-made institution, not only giving

to each certain rights and privileges, but also placing on each heavy

duties and exacting from each serious obligations. The instinctive grasp

of this truth by the British people gives them their respect for law and

makes them as a nation, in this regard, unique in the annals of history."

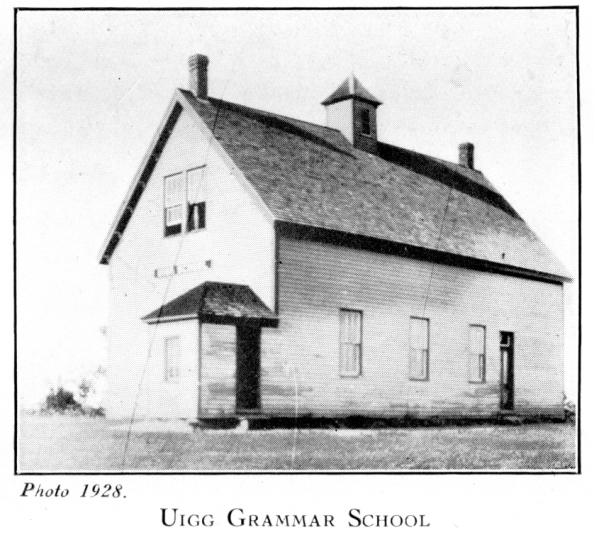

UIGG GRAMMAR SCHOOL

"Again I revisit the hills

where we sported,

The streams where we swam, and the fields where we fought;

The school where, loud warn'd by the bell, we resorted,

To pore o'er the precepts by pedagogues taught."

The first settlers in Uigg

were as zealous for learning as for righteousness. Their descendants of

the next generation were notable for the same qualities. Their school

became a marked one, and in all Canada none of similar grade, has a finer

record for an equal period of time. Since 1878 this school has had two

classrooms, and until 1909 all teachers came from families residing in the

district. During all that time numbers of scholars graduated from it, took

special training and taught in various other schools throughout the

province.

These teachers were

conscientious young men and women. Eager in their pursuit of knowledge,

they inspired those under them with their infectious enthusiasm for

learning. They generally taught for two or three years and then pursued a

course of higher study in universities in the other provinces, in the

U.S.A., and sometimes in Europe.

Dissension in the school

was unheard of. Each family regarded the little academy as in its own

especial care, and whatever service was required, if tending to add to its

honor and success, was given freely with eager enthusiasm and

cheerfulness. The success of the neighbor's child was a personal success

reflecting honor, not only on the school, but on each and every family

belonging to it.

The sympathetic attitude of

the ratepayer stimulated the teachers to do their best. They knew their

efforts were appreciated, and there was thus a bond between teacher and

pupil rarely found in any other public school.

The pupils were tidy, clean

and intelligent. The district being entirely Highland all could speak

Gaelic, but at first all could not speak English. A distinct Gaelic accent

was inevitable, and men from Uigg, who have never spoken Gaelic, carry the

accent through life.

There were two classes in

the Principal's room. The lower of these studied text books on English

history, arithmetic, reading and writing. After passing into the highest

grade Latin, algebra, geometry, French and geography were added. There was

a blackboard for each class, also an atlas. The pupils were given problems

to do at home, especially sketches in geography and short essays on

subjects read or expounded in class.

In the eighties Malcolm

MacLeod, K.C., presented an organ to the school. For many years, until

destroyed by irreverent mice that nested in it, the scholars received

great profit from the half-hour weekly song service. Being exceedingly shy

this service helped to develop a self assurance and confidence which was

often lacking in the country bred child.

The Principal taught the

more advanced pupils for half an hour after the usual time for closing.

They studied Greek, trigonometry, advanced geometry, and other subjects.

Every morning when school opened each pupil in the Principal's room read a

verse from the New Testament. After roll-call the day's work began.

The first building was

erected of logs about 1840, near the present Uigg railway station, but on

"the west side of the Murray Harbor Road, and on the north side of the

brook.

The following reference is

from an old newspaper in the possession of Hon. D. A. Mackinnon, K.C.,

Charlottetown:

A SHORT ACCOUNT OF A LOG

SCHOOLHOUSE AT ORWELL OR UIGG

"The first school houses

were little log huts without any floors except the native earth. For a

chimney two logs standing upright in the middle of the room, about three

feet apart, served as jambs between which the fire was built to warm the

children all around. On the top of these perpendicular logs of about four

feet in height, was constructed the cob and clay work, namely: a mixture

of mud and ferns between sticks, with the ends of each crossing those of

the other like the walls of a log house. This formed the funnel aperture

to throw off the smoke. Around this primitive and odd fireplace marched

the monarch of the birchen rod and sceptre, with as much dignity over his

mud floor as ever did Commodore of a large fleet over his quarter deck."

This building was replaced

about 1849 by a frame structure, which was larger than the average one

room country school of the present day. It stood a few hundred feet south

of the present Uigg railway station, but on the west side of the road.

William M. Macphail, of

Portland, Oregon, has a clear recollection of the building. A retentive

memory under any circumstances, there was imprinted on his mind an image

of the building, doubly clear from the fact that, as a child, his first

day in school was spent in it. This was the last day it was used as a

schoolhouse. There, with awe, he was shown the aperture in the ceiling

through which offending Youth was forced to climb, and, in the Stygian

darkness of the low-roofed garret, atone in glommy silence and alone for

misdemeanors done below. The menacing forms of ravenous rats and hungry

mice, eagerly gnawing the surplus scraps from pupil's ample meal, assumed

vast proportions and dreadful form in the innocent mind of the terrified

child. The prescribed period of atonement over Guilt descended to the room

below, there to meet and suffer an even more unendurable fate, the

scornful merriment of inconsiderate Youth.

Captain Neil Murchison of

San Rafael, California, who was for a short period an attendant at this

school, recently related the following incident:

One of the most noted

masters of this old academy had decided on a visit to Charlottetown. He

arranged that the school should be conducted by one of the older pupils in

attendance during his absence. Circumstances, however, rendered the

contemplated trip unnecessary, but so great was his interest in, and love

for those under his care, that he could not refrain from attendance at his

post of duty.

Arriving at the old school

before even the most ardent football enthusiast appeared, he secreted

himself in the dark forbidding garret, undismayed by hungry host of

cunning rats and timorous mice. There he remained in secret silence, his

mind noting with matchless grasp the actions of the various pupils in

whose welfare he had such profound paternal interest. Not until the noon

hour came and all had disappeared did he withdraw from his retreat,

undiscovered by those whose actions he had so critically appraised.

This, the second Uigg

schoolhouse, was used for the purpose for which it was erected until 1878,

when it was vacated. Shortly thereafter it was moved to Kinross corner,

and there used as a store by the owner, John J. MacLeod. The upstairs was

converted into a hall, and within its walls the youth of the neighborhood

received instruction in the value of sobriety and the folly of

intemperance. It was also used by Thomas Richards, the music master of

Alberry Plains. Here, on winter evenings, he taught his classes the

rudiments of the science of music. It was in a very real sense a modern

community centre, and for many years the various lectures, concerts,

socials, magic-lantern shows, and other forms of amusement held in it,

brought much happiness to the youth of the district. It was later moved to

the farm of Mr. MacLeod in Uigg, where it now stands.

In 1878 the school trustees

of the district, with the wisdom characteristic of those who have held the

office for generations, erected a new frame schoolhouse, twenty-four feet

wide by forty-five feet long, divided into two classrooms below, and

public hall above, which they built that summer. This well proportioned,

comfortable building, between 1878 and the present day has been the home

of an educational institution, of its kind unsurpassed in the annals of

Canada.

This building was erected

by Peter Martin of Newtown, on the front of James Campbell's farm, about

three hundred yards north of the site of the old schoolhouse. Probably the

most imposing country school in the province when erected this structure

is today, after the lapse of over fifty years, a modern building, suitable

in every respect for the purpose for which it is used. Enshrined about it

are memories dear to the hearts of those who received instruction within

its walls; memories of the kind that hold its former pupils, wherever they

may be, with bonds of the deepest affection.

In the hall above the

school classrooms, were held a debating society and occasional social

gatherings in the winter evenings. The political meetings held there from

time to time were attended by the men within a radius of many miles. The

simple honest audience was greatly impressed by the learning displayed by

the various candidates, generally inconspicuous country lawyers. Their

ready flow of vigorous language, punctuated by occasional sallies of wit,

amused, even if it did not instruct the hearers.

Of the descendants of the

Uigg colonists now living no one is so well equipped to connect the

present with the past as Rev. Donald Gordon Macdonald, who was born in

Uigg, February 1843. At eighty-six years of age Mr. Macdonald's memory is

unimpaired. He preaches' almost every Sunday in various Baptist churches

in and around Vancouver, where he now resides with his wife, Minnie Jane

Schurman, a member of a notable Canadian family, the Schurmans of Bedeque,

Prince Edward Island. Her brother is Jacob Gould Schurman, at present

American Ambassador to Germany.

In recent conversation Mr.

Macdonald recalled some of the well known characters in the settlement

during the time of his youth.

"While quite a young boy,"

he said, "I lived with my brother, Malcolm, a merchant of Belfast Cross,

now Eldon. Here I was known as `Little Donald at the Cross.' While living

there I was well acquainted with the Belfast minister, Rev. Alexander

MacLean. He was an able preacher and well-liked minister.

"While living in the

community I attended the small Baptist meeting house near `the Cross,'

which was attended by the few Baptists in the district. There was `Big

Rory' McLeod and family, a few Frasers, Martins, and Macdonalds. The

latter family lived at Pinette, and were marked in that there were four

Johns in the family-the father and three sons all bearing the same name.

To distinguish them they were known as John the Baptist (the father), John

Small, John Ban, and John. John Ban became a Doctor of more than average

skill, and a preacher of more than average ability. At an early age he

moved to the U.S.A.

"At this time my old

neighbor in Uigg, Rev. Samuel McLeod, frequently preached in the Baptist

church near by. He traversed the six miles from Uigg on horseback seated

on a saddle of plaited straw, made by himself . Passing a group of young

boys one day they laughed in derision at his humble saddle. His only

comment was `you need not laugh at my saddle, boys; every cent of it is

paid for.'

"Samuel McLeod, like the

other immigrants who landed in Charlottetown on the 'Mary Kennedy,' May

31, 1829, had adhered to the Presbyterian Church in Scotland. While

engaged as a schoolmaster in Skye, for conscientious reasons, he had

allied himself with the Baptists, and made a public confession of his

faith by immersion. For this he was waited upon by the school trustees and

asked to resign. Owning the chair on which he sat, he replied 'I am more

independent than His Majesty, our King. If he is dethroned he must leave

his throne behind, but I take mine with me.' With his chair upon his

shoulder he joined the departing settlers, and in the new land exerted an

influence for good over a whole countryside.

"The following incidents

may help show the moral authority exercised by Mr. McLeod over those who

came within his influence.

"Two Roman Catholics, one

of them a neighbor of Mr. McLeod, were engaged in heated controversy.

Finally the neighbor said to his opponent `It is folly for you to deny it,

for with my own ears I heard Samuel McLeod say so.' The Irish disputant

said 'Begorra, if Samuel McLeod said so, I believe it.'

"On another occasion two

serious minded young boys were discussing the Day of Judgment. One said to

the other, 'Where would you like to be on the Day of Judgment?' 'Inside

Samuel McLeod,' was the prompt reply.

"Like his neighbors this

noble man worked with his hands, six days in the week, to clear the

primeval forest and create a home for himself and his family. On the

seventh day he preached to them the Gospel, and by counsel and advice

strove to lighten their load and improve their lot in the land of their

adoption.

"Another man whom I recall

vividly was the talented Daniel McKinley from a district near

Charlottetown, who, about 1853, taught for a few months in the Uigg school

and preached in the Baptist church. He posessed much more than average

ability. Overstudy broke his health, and thereafter his life was devoted

to a study of the Bible almost to the exclusion of every other interest.

He could read it in seven different languages. The question of believer's

immersion for baptism, instead of infant sprinkling, became for him a

subject of supreme importance. He preached it everywhere, but his favorite

method was to attend the church services of other denominations and sit

near the door in order to be first out. He took his stand outside and

preached to the retiring congregation. To any question asked he was ready

with a reply, frequently to the amusement of the assembled crowd.

"On one occasion he

attended the Murray Harbor Road church on Sacramental Sunday. Rev. Donald

Macdonald, the minister, was conducting the service. McKinley began

preaching by the roadside, and drew away some of the congregation from the

service. Two of the elders advised him to desist. When he continued they

carried him away bodily. In his clear stentorian voice, heard above the

voice of the minister, conducting the service, he cried aloud, `I am more

highly honored than my Blessed Master. He was carried on one ass; I am

carried on two.'

"At the close of a meeting

in Pownal, the pastor (I think his name was Berry) whose limb had been

amputated in England, to break the force of McKinley's argument for

complete immersion, said: `You could not carry out your theory in my case,

for my limb is in England, and I am here.' `It is better,' said McKinley,

`for you to enter into life maimed than having two limbs to be cast into

hell fire.' To this the pastor replied, `The only immersion I find in the

Bible is the immersion of swine. They ran down into the sea and were

choked in the water.' McKinley replied, `The swine themselves had more

sense than you Methodists. They went into the water to get clear of the

devil, but you won't.'

"On another occasion

McKinley went to St. Peter's Anglican church, Charlottetown, then, as now,

noted for its High Church practices. What he heard and saw so grated on

his sensitive mind that he could not endure it to the close of the

service. Taking hat in hand he started for the door. On reaching it he

turned, and' facing the officiating clergyman said in a loud voice,

'That's what I call the fag end of Popery.'

"On another occasion I had

a serious talk with McKinley over this question of baptism. I suggested to

him that he was putting too much emphasis upon it. I pointed out that

baptism is not a condition of our salvation, but rather an evidence of it.

We are baptized because we are saved, not in order to be saved. 'Yes,'

said McKinley, 'but you must ask them to go farther than is necessary in

order to get them to go far enough.' "

For generations the

acknowledged leaders at the bar, and in medicine on P.E.I. came from Uigg.

Thence also came Sir Andrew Macphail, great in scholarship, distinguished

in letters. His grandsire, William Macphail (1802-1852) of Nairn, Scot.,

together with his wife, Mary Macpherson (1804-1888) of Kingussie, and

family, emigrated to Prince Edward Island in 1833. Their gifted son

William (1830-1905), and his wife, Catherine Smith (1834-1920), parents of

Sir Andrew, had the unique distinction of having a family of ten children

of whom five sons and two daughters were university graduates of unusually

distinquished records. At an early age he possessed a mind stored with the

richest treasures of Scottish history, and a character moulded in the

definite and fixed standards of a nation in which character building was

one of the chief preoccupations of the people. From the first he was a

conspicuous man. His acute mind, terse and vigorous speech, marked him for

preferment, and soon, as school inspector, by his zeal, eager enthusiasm,

and unselfish devotion to the cause of education, he laid, not only the

district in which he lived, but the whole province, under heavy obligation

to him for the impetus given to that sacred cause. His success in

inspiring those who came under his influence with a love of the higher and

nobler things of life was great, and many men and women in later life have

testified to the great debt they owe that remarkable man.

REV. DONALD MACDONALD

The Macdonaldites

The majority of the

Presbyterians who settled in Murray Harbor Road and in Uigg in 1829 became

followers of Rev. Donald Macdonald. This extraordinary man was the son of

Donald Macdonald and his wife, Christine Stewart. The father's Jacobite

sympathies were strong enough to lead him to face the King's troops at

Culloden. Later he settled in Perthshire.

In addition to Donald,

there were among other issue, Robert, of Perth; Duncan, and Findlay, of

Orwell.

Donald was graduated from

Saint Andrews University in 1816, and was ordained the same year. He

emigrated to Nova Scotia in 1824 and settled in Cape Breton Island. He

came to Prince Edward Island in 1826.

His brother, Findlay, had

emigrated to Prince Edward Island about 1825, and settled near Georgetown.

In 1829, or early in 1830, Rev. Donald was invited to Murray Harbor Road

to preach to the newly arrived settlers, and liking the locality induced

his brother, Findlay, to move to the two hundred acre farm half a mile

east of Orwell Bridge, on the road to Kinross. Rev. Donald died February

21st, 1867. Findlay was then eighty-six years of age.

Mr. Macdonald was preaching

at Birch Hill, Lot 48, when John Martin, Donald MacIan Oig McLeod, Murdoch

Mackenzie, and other settlers, heard of his ministry. They conferred

together and decided to send Donald MacIan Oig and Murdoch Mackenzie to

hear him preach. If they reported favorably a "call" was to be extended to

him to organize a church in their district. These emissaries were

captivated by the magnetism, fiery enthusiasm, and obvious sincerity of

the man. A feature of his service with which they were unacquainted was

the "works" or trancelike ecstasy, accompanied by gesticulation and

shouts, which overcame many of the audience. Donald took it upon himself

to give the neighbors who gathered in his house to hear the report of the

delegates, a physical demonstration of what he had seen. Donald MacIan Oig

was a tall man. The ceilings were low. The beams were knotty. His first

leap brought him in violent contact with the timbers overhead. His wife

rushed for bandages, but he had caught already the infection of a religion

he never forsook, and forbade her, saying "This guilty head, let it

bleed."

The new minister came and

preached in the barn on Angus Martin's farm, later Peter Musick's. His

magnetism was infectious. Soon a body of loyal followers gathered about

him and the Murray Harbor Road church became the nerve centre--of a parish

which extended from end to end of the Island. Some, like the Lamonts, came

and settled in the district to be near their beloved leader. Rarely has

any pastor ever had a more loyal and faithful congregation than that

gathered around Rev. Donald Macdonald, and rarely has a congregation been

ministered to by a more tireless, enthusiastic, and effective leader.

While he lived, and for years after his death, it was the practice in this

church for the men to sit on one side of the church, while the women sat

by themselves on the other side. In the long journeys between his various

preaching stations he endured discomfort and great hardship. He never

failed a waiting congregation, although frequently beset by the violent

buffetings of the tempestuous island winter. Bitter cold, driving snow, or

lashing rain were only a challenge to his unquenchable zeal.

Mr. Macdonald believed in

celibacy, and in this and other respects was able to, and did, practice

what he preached. The advantage of this condition, to a man ministering to

so widespread a congregation, was incalculable. No man subject to the

various distractions of married life could possibly have accomplished what

he undertook and did. Cut off, as he was, from the refining and mellowing

influences of wife and family, he developed a reserved dignity of exterior

while yet retaining a warm and tender heart within. When a member of his

congregation started out with her crying child, he called after her "sit

down woman, and teach your child obedience." The kindly gentle mother sank

into the nearest pew overcome, but so well understood was the greatness of

the man that no resentment was harbored by the one whom he had rebuked.

When Angus Joiner (McLeod),

while yet a young man, became a convert of Mr. Macdonald, he was

admonished by him to put aside the violin he loved to play "as belonging

to the flesh." Angus took it out and destroyed it with an axe.

Every man was influenced by

his environment and so was Mr. Macdonald. His place was with the afflicted

and distressed, with the sick and the dying. He was not called where there

was gaiety and merriment. He took on the atmosphere in which he lived, as

do all men. But if he was not their intimate in joy, he was in that

emotion that is even more universal-sorrow. Through this common bond he

entered their inmost hearts and became the constant friend and confidant

of all.

Whenever grief entered the

home the form of the beloved pastor followed close behind to chase away

their sorrows, with the sunshine of an understanding sympathy, and a

desire to serve that knew not labor.

Hence it was that when the

body, broken in the service of others, was carried to Orwell, to the home

of his brother, Findlay, there to die, tears coursed down the furrowed

cheeks of stern men, as they looked for the last time upon the austere

face, guardian of the tender heart, that never failed them in the hour of

their adversity and of their sorrow.

On the monument erected to

his memory in the Orwell Head churchyard is the following inscription with

a Gaelic translation:

In Memory of

REV. DONALD MACDONALD

Minister of the Church of Scotland, who was born

January 1st, 1783, in the Parish of Logierack

Perthshire, North Britain. Educated in the University

of St. Andrews, and ordained by the Presbytery of

Abertaill in 1816.

He emigrated to America in

1824, and laboured

in his Master's cause on the Island for nearly forty

years, with many tokens of acceptance.

He died on the 22nd day of

February, 1867,

in the eighty-fourth year of his age, and the fiftieth of

his ministry.

Rev. Mr. Macdonald was the

first person interred in the Murray Harbor Road churchyard. James Campbell

of Uigg was the first interred in the kirk cemetery on the front of Samuel

Martin's farm, near the junction of the Dundee road and the Murray Harbor

road.

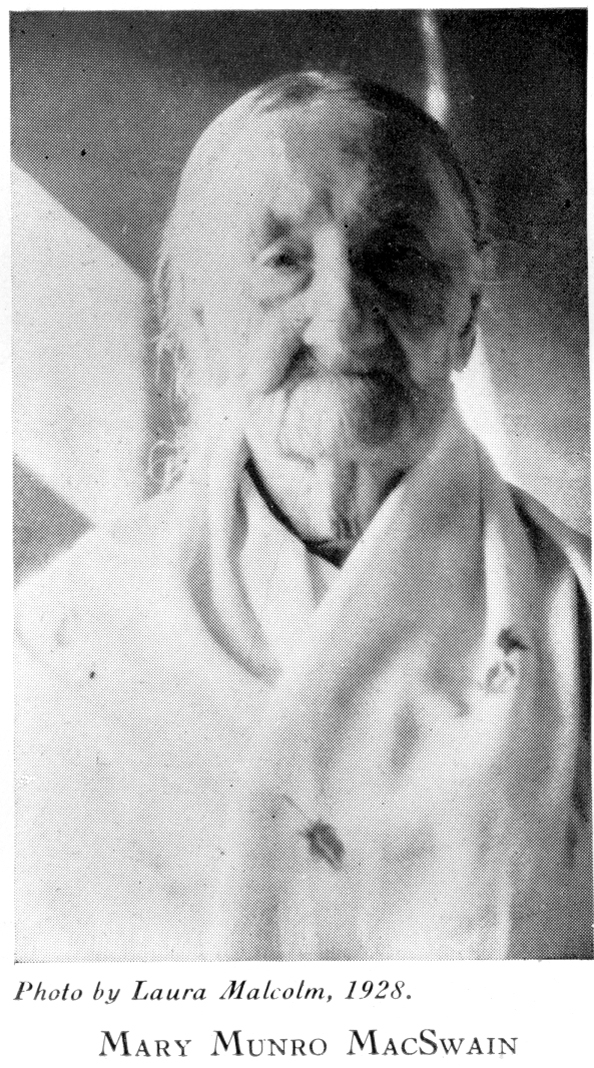

One of the oldest women

living today is Mary Munro, widow of Allan MacSwain of Lorne Valley. She

was born at Shawbost, Parish of Lochs, Lewis, in 1834, and emigrated with

her family to the Orwell district in 1842. Her twin sister Anne, died only

two years ago. For a person of her age she possesses remarkable hearing

and memory. Few people have had her variety of experience. Pioneering for

almost a century, few now living know more of early days on the Island

than she.

Quite recently several

friends visited this gentle old lady at the home of her nephew, Daniel

MacSwain, in Lorne Valley. Her interest in the things of every day life

was a surprise to those who met her. Although it is almost ninety years

since she left the land of her birth, with true Highland sentiment her

mind returned to those early days of happy childhood in the glens of far

off Lewis and Skye.

"Although born in Lewis,"

said she, "my father was a native of the Parish of Kilmuir, Skye. He was

one of that noble band of Scottish schoolmasters and catechists, who held

aloft the torch of learning and religion in their own and in foreign lands

to such purpose that the name Scotland became synonymous with intelligence

and honor the world over. For many years he taught and preached in Skye,

but when I was born he was teaching in Lewis. The schoolmaster's wage was

small, as is proved by various receipts signed by my father in a little

Day Book, once owned by a Skye shopkeeper, but now possessed by my nephew,

Dr. Alexander Allan Munro of New York.

"`Received from Alexander

Duncan, Esq., Treasurer to the Honorable Society in Scotland for

propagating Christian Knowledge, the sum of seven pounds ten shillings

sterling, being the amount of my salary from the first day of May to the

first day of November last, as schoolmaster at Fernlea, in this Parish,

which sum I hereby discharge the said Treasurer.

"'Witness my hand at

Fernlea, Parish of Bracadale, this 29th day of January, eighteen hundred

and twenty-two years.'

Sgd. ALEX MUNRO.

"For generations the Munros

were preachers and teachers and many of them follow these vocations

today."

"The first recollection I

have, certainly the first that can be fixed definitely," continued Mrs.

MacSwain, "was the death of King William IV. My father came into the room

where we were sitting and spoke to mother. She raised her apron to her

face and burst into tears. This was the first time I ever saw my dear

mother cry, so I became alarmed and cried too. This started my twin

sister. Mother then took us both in her arms and petted us. `The king is

dead,' she said, `don't mind, everything is all right, we are going to

have a little girl Queen.'

"I recall that everyone was

talking America and how prosperous their friends there were. There seemed

to be dissatisfaction and unrest. Times were hard and getting harder.

Finally, after much anxious thought, my father decided to sever the

age-long tie that bound us to the Hebrides, like oaks to the very ground.

We packed up the few indispensable worldly goods and started for Prince

Edward Island."

"I can yet see," she went

on, "the coast of that land of promise looming up ahead of us as we

approached its shores. After visiting relatives in Orwell and Alberry

Plains, we took up land with other Gaelic speaking settlers in Brown's

Creek. We were not long in our new homes before father, ever following the

lure of education, helped to organize a school. A Free Church congregation

was also soon established. The ardor of the people for it almost partook

of hostility to the neighboring Established Church at Murray Harbor Road.

The 'Disruption' had recently taken place in Scotland. The newly arrived

immigrants were keen partisans, and bitter foes of the Establishment."

"But," said Mrs. MacSwain,

"our Highland blood kept us moving and once again we broke up our home.

With several neighbors we moved to the Head of Cardigan, then one of the

most heavily wooded districts on the whole Island. No one can realize the

toil involved in clearing the maples. The stumps never seemed to die.

However, we stuck and this move proved our last. We liked to visit our old

Brown's Creek neighbors, and we frequently drove across country on

Saturday for the Sunday service, staying with friends over the weekend.

Among the adherents of this congregation was William Lamont, the only

member of that devoted church family not a follower of Reverend Donald

Macdonald. Although not a gifted singer William Lamont was an expert

`liner.' This was an important part of the precentor's duty, and it was

well performed by him. At a time when each person in the audience did not

possess a book, it was necessary, if all were to sing, for someone at the

beginning of each line or two to intone the words in a voice heard by the

whole audience. This was known as `lining.' Once done each person had the

words, and was thereby enabled to raise his voice in song. All sang, and

sang fervently, and if all did not pray, those who did appropriated the

time that would have been taken up by others had all prayed. The result

was hearty, refreshing singing, and long tedious prayers.

"On one of these occasions

the Cardigan visitors were holding a service on Saturday evening at the

home of one of their Brown's Creek friends. William Lamont was lining, and

all present were entering with the greatest fervor into the song. It was

fall, and Boreas smote the log walls of the humble cottage with bitter

blasts. The household dog had been driven from his accustomed haunt beside

the open hearth, to make way for the press of visitors. Towards the end of

the first song, a dismal howling was set up by the faithful Achates

without, his spirit moved as much by the mournful and unusual harmony

within, as by the bitter blasts without. At length the song was ended. The

last note had scarcely died away before the precentor, in the same

wavering tone, and with the same fervid expression, carried on in Gaelic,

'Chaidh Satan a steach do'n choin' (Satan has entered into the dog).

Thinking him still `lining,' the congregation, swept along by the

enthusiasm of the occasion, took up the refrain, and from every throat

there arose, loud in unison, 'Chaidh Satan a steach do'n choin.' But if

His Satanic Majesty had entered into the dog, as alleged by the respected

precentor, his sojourn in the canine host was of short duration, for there

was ample evidence in the frequent fistic encounters between the more

quarrelsome members of the two rival religious factions, at casual

meetings over the flowing bowl, that he soon freed himself from the

restraints of his shaggy habitation, and invaded the more congenial soil

of the human heart."

"What do I think of our

young folk today?", said Mrs. MacSwain, repeating the question of one of

her visitors. "Well, although I do not read many periodicals or

newspapers, I do not agree with the criticism I sometimes hear and read of

the character of the modern girl. After almost a century of association

with my friends and neighbors I must say that human nature does not differ

appreciably today from what it was when I was a child, or during any

period since. The fact of the matter is, too much stress is laid today on

formal education. I have met women in rude surroundings possessed of as

much refinement of mind and gentility of manner as is found in those

reared today in luxury. Youth makes its mistakes, no matter what the

circumstances."

Mrs. MacSwain does not look

like a person who ever endured great physical hardship. When one of her

guests referred to the freshness of her complexion, her face lit up with

animation.

"My continued good health,"

she said, "is due to the simplicity of our lives. We never indulged

ourselves. Our surroundings were healthful and natural. We were taught to

face the future with a fortitude that is not looked for in women of the

present age. For women to give way to tears was considered unseemly. In my

early years it seems to me that women were almost as strong physically as

men. I have seen cases of harrowing misery caused by intemperance. The

curtailed use of intoxicants has already done more to lighten the burdens

of the poor than any single agency operating in the century of my

existence."

Mrs. Norman MacLeod, of

Vancouver, when discussing early Belfast shortly before her death about a

year ago, told of herself and two sisters having received collegiate

training. Her brother, Angus MacSwain, was graduated in arts and medicine

from McGill, and Harvard, and later took post graduate courses in European

universities. Other families had a similar record.

"Parents in those days,"

said Mrs. MacLeod, "were anxious to educate their daughters, but the times

were hard, and it was difficult to pay for the education of more than one

or two members of a family. At that early time the economic freedom of

women had not been realized; it had not even been attempted. The only

vocation in which she could hope to use a specialized training was school

teaching. The few who received high school training became teachers."

Mrs. MacLeod was of the

opinion that though the vast majority of the women of early Belfast went

to the common country schools only, they were thoroughly grounded in the

fundamentals of education. "The first lesson," said Mrs. MacLeod when

questioned on that point, "impressed upon the mind of the young girl was

never to strive to do or to think as men did or thought, but to do and to

think in a way befitting the physical and mental character of those of

their sex. It was considered quite enough if a girl was able to do well

those things that more fittingly fell within their province. Women of past

generations were not as cultivated as are modern women, but they were

endowed with equal refinement. Their influence in the home was as potent

as is that possessed by their modern sisters."

"In looking back,"

continued Mrs. MacLeod, "over the list of Belfast women, there comes to

mind the names of many of great charm and refinement. Among them none made

a more indelible impression on my mind than did Mrs. Donald A. MacLeod of

Eldon, formerly Miss Ann MacKenzie, sister of Findlay MacKenzie, [Father

of Dr. David `'V. MacKenzie, the eminent surgeon of Montreal. ] and

Captain Roderick MacKenzie of Flat River. Never in my life have I met a

woman of higher culture and greater charity than that wonderful woman.

About her there centered to the end, which came only a few years ago, when

she was over ninety-one years of age, the distinguished and charming

family of sons and daughters, who gathered each summer at the old home,

attracted by one of the most beautiful characters it has ever been my

privilege to know."

The Mackenzies of Belfast

as a clan were noted for nobility of looks and character. Even among them

Mrs. MacLeod was pre-eminent.

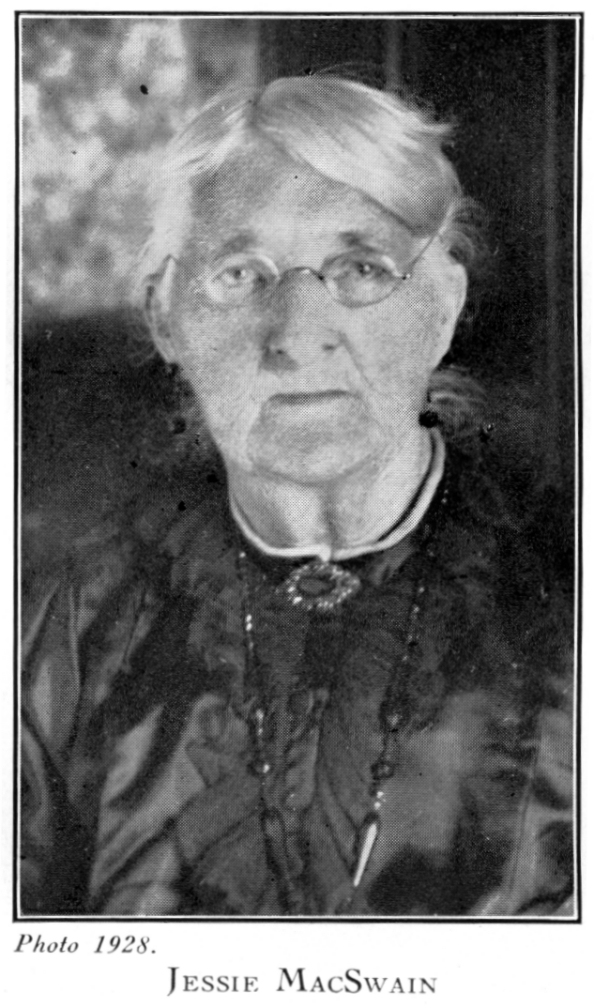

Another interesting old

lady, full of the lore of old Belfast, is Jessie, daughter of William

MacLeod, of the Glashvin, Pinette family of that name. Her father fought

in the Napoleonic Wars, and from his own lips she heard many romantic

tales of stirring scenes in foreign lands. Although eighty-nine years of

age her memory and hearing are unimpaired.

William Saighdear, as he

was commonly called by his Gaelic speaking neighbors in Uigg and Orwell,

was a sergeant in the 42nd Highlanders-the famous Black Watch. He enlisted

when sixteen years of age, and continued with the colors for twenty-one

years, when he was honorably discharged with several medals and a pension.

After returning from the wars he married Catherine Macpherson. In 1831 the

family emigrated to Uigg, P.E.I., and here in 1840 Jessie, the youngest

and sole survivor of their ten children, was born. Her husband, Angus R.

MacSwain, Lorne Valley, died a few years ago, and she now resides with her

daughter, Christine A. Gurney. She is perhaps the only woman now living

whose father fought at Corunna. She recently spoke of him as follows:

"He stood six feet three

inches, and was a magnificent specimen of manhood. Skye gave many such men

to the British Army. Their bravery did much to augment Britain's glory. He

had many harrowing experiences in the Peninsular War, through which he

fought under Sir John Moore and Wellington. On three occasions bullets

were extracted from his body, and on one occasion he received a sabre

wound in the shoulder. At Corunna he was left badly wounded on the field.

An English officer and orderly came upon him. The orderly examined the

wounded Highlander and told the officer that he was too far gone to do

anything for him. On hearing this, father, turning to the orderly, said,

`If I had a bullet you would lie with me.' The brave and compassionate

officer was so struck by the undaunted bearing of the man that he said,

`This is a brave man, we will take him.' So saying he dismounted and

together they placed the disabled soldier on the horse. Coming to a house

near which goats were feeding, they asked a woman for milk for the

suffering man, and a bandage for his wounds. She immediately tore a strip

from her chemise, and with this his wound was bound. After recovering he

fought in many more of the bloodiest battles of the War, receiving wounds

but finally returning to England.

"In Waterloo he was shot

through the abdomen, and thought his end had come. He recovered, however,

and returned to Skye. In Uigg and Head of Cardigan, he underwent the many

and varied hardships of pioneer life without complaint. Finally his

powerful frame and masterful spirit succumbed to the hardships he had

undergone. They carried him from Lorne Valley to the Belfast churchyard,

and there they left his remains among the clansmen he had followed to

their home in the new land. His devoted wife, my ever kind mother, rests

by his side."

UIGG OF TODAY

For three generations after

its settlement Uigg, like Belfast, remained a remote, isolated district.

Untouched by the surging mass of humanity that swarmed over the continent,

its frugal and industrious residents retained the customs and beliefs of

their forefathers to a degree rarely found elsewhere. Those who never left

its shores thought the little isle on which they lived the centre of all

things, and those living beyond its shores were looked upon and referred

to as foreigners. Their business was done with Boston, and that home of

culture was better known by many of them than hamlets a few miles distant

from their birthplace. It was in the U.S.A. that the surplus population

sought and found employment, and there were few Belfast homes but had sons

and daughters prosperous and loyal citizens of that great republic. The

bond of sympathy for America was strong, and for years many hoped for

political union with the States.

About twenty years ago,

when the first train steamed into Uigg, the district awoke from its long

sleep. It is no more a remote, out-of-the-way, isolated district. Trains,

automobiles, telephone and telegraph have brought it into close touch with

the outside world.

The entire population

devotes itself to farming. Each homestead generally consists of one

hundred acres. The dwelling houses are commodious and comfortable. Most of

them are built of native spruce and fir, which is sawn in local mills. A

few have hot-air furnaces, some of which burn hardwood from the little

groves wisely preserved on almost every farm. The early settlers grew oats

so persistently that the soil became greatly impoverished. In late years

it has been restored to its former fertility through rotation of crops,

fertilizers, and raising of stock. For the past few years large quantities

of certified seed potatoes have been grown. These are shipped to points as

far afield as Cuba, and the Carolinas. Co-operative marketing has

superseded individual effort, and now eggs, cattle, sheep, pigs, potatoes,

and all the products of the farm are handled through the various pools

organized for the purpose.

One of the most notable

changes in Uigg is that in the home. In the early days a family of ten

children was not uncommon. There were several of twelve and one of

fifteen. Today a family of half a dozen is rare. The effect on school and

church is depressing. The old enthusiasm is lacking and there is a

slackening in effort and attendance.

But nothing can rob Uigg of

the glory of its past, and there will cling to it always something far

above material things. The memory of its pious, law-abiding, God-fearing

men and women will long be cherished by such as love nobility of character

and upright conduct. The high tradition of the founders has been in large

measure maintained by succeeding generations, and now a century after the

first settlers set up their temple in the wilds of Uigg, their descendants

may proudly claim that, in the century of its existence, no resident of

that much loved spot has ever been charged before a court with the

commission of a crime.

"But if, through the course

of the years which await me,

Some new scene of pleasure should open to view,

I will say, while with rapture the thought shall elate me,

`Oh! such were the days which my infancy knew!' "

|