|

Horace Walpole calls the year 1759 the ' great year

the ' wonderful year because of the victories which

it brought to his country. France and Britain were

in the midst of the terrible Seven Years' War, which

involved the loss of nearly a million lives. The

outcome of the war was still uncertain. During the

summer the English people had been uneasy. France

was known to be making great preparations to invade

Britain, and many a good citizen went to bed each

night in dread lest the roar of the cannon of the

invader might be in his ears before morning. Wolfe

had just led a great expedition to Quebec, but

already there were gloomy forebodings that his

attempt would fail. News travelled slowly in those

days, and it was not until the early autumn that

good tidings arrived. Word then came that at the end

of July General Amherst had captured Ticonderoga,

the fort which commanded the entrance to Canada by

way of Lake Champlain, and that at the very same

time Sir William Johnson had captured Fort Niagara,

the key to the whole commerce of the region beyond

Lake Ontario. England was exultant. Horace Walpole

wrote on September 13, 1759, the date, though he did

not yet know it, of another and greater victory in

Canada : ' We have taken more places and ships in a

week than would have set up such pedant nations as

Greece and Rome to all futurity. If we did but call

Sir William Johnson "Gulielmus Johnsonus Niagaricus"

and Amherst "Galfridus Amhersta Ticonderogicus" we

should be quoted a thousand years hence as the

patterns of valour, virtue, and disinterest^ ness ;

for posterity always ascribes all manner of modesty

and self-denial to those that take the most pains to

perpetuate their own glory.'

The

exultation caused by the fall of Ticonderoga and

Niagara soon gave way to new fears. Word came from

Wolfe that Amherst had failed to join him before

Quebec and that he had little hope of capturing the

fortress. This news was made public, and, of course,

caused gloom and depression. Almost immediately

after this came, however, the tidings that Wolfe had

won a great victory and that Quebec had fallen.

Walpole expresses the pride and joy of the time. He

now jested at the fears of invasion and at the

weakness of the French navy: 'Can the lords of

America' he asked, 'be afraid of half a dozen

canoes?' The bells, he said, were being worn thin

with ringing for victories, and one was forced to

ask every morning what success there was for fear of

missing one. ' I don't know a word of news less than

the Conquest of America,' he writes to his friend

Montague, on October 21: 'you shall hear from me

again if we take Mexico or China before Christmas.'

The English, he added, were like Alexander: they had

no more worlds left to conquer. He affected to be

bored by meeting so many people who had won military

honours; it is 'very fatiguing: all the world is

made knights or generals '. There was nothing in all

history, he thought, to equal the victories of this

year.

The

simple-minded public, which received this joyful

news, now assured itself that the struggle was over

and that Canada had fallen. It dismissed America

from its thoughts. The newspapers of the time make

hardly any reference to the later campaign in that

part of the world. Only when, seven months after the

September day of Wolfe's victory, the British met

with bloody defeat on the very ground where he had

triumphed, did the nation realize that France still

fought for the mastery of Canada. the deuce was

thinking of Quebec?' wrote Walpole in June 1760;

'America was like a book one has read and done with

. . . but here we are on a sudden reading our book

backwards.' He mourns over the 'rueful slaughter' of

brave men and concludes sadly that 'the year 1760 is

not the year 1759'. During the year 1760, however,

British arms were to achieve the final conquests in

both India and Canada which the victories of 1759

had left still uncertain. In Canada, with which

alone we are here concerned, the struggle carried on

between September 1759 and September 1760 lays bare

the condition to which France's great colony had

been brought. We find in a survey of those last days

of New France much that helps to explain the later

history of the French race in Canada. We therefore

take up the story from the moment on September 13,

1759, when Wolfe's musketry had shattered the French

lines on the Plains of Abraham and when the fate of

Quebec was still doubtful.

The

game of war has never been played in surroundings

more striking than those at Quebec. The mighty

current of the St. Lawrence, contracted here to a

breadth of about a thousand yards, washes the base

of the high cliffs on which the stronghold stands

and then broadens into a great basin four or five

miles wide. On the east side of the basin the

beautiful island of Orleans divides the river into

two channels, a narrow and intricate one at the

north, a broad one at the south. The deep blue of

the silent, forest-clad mountains, the clear air,

the rushing tide of the spacious river, are all

elements in a scene of entrancing beauty. Quebec

stands at the east end of a plateau seven or eight

miles long and in places two or three miles wide.

Though the fortifications were insignificant, Nature

had made the place almost impregnable. At the north

the River St. Charles flows into the St. Lawrence

near the base of the high ground and constitutes a

natural and difficult ditch for the assailant to

cross. On the east and the south side the plateau

falls in steep cliffs to the strand of the St.

Lawrence. On the west side the drop to the valley of

the Cap Rouge River is not less sheer.

Wolfe's problem had been to reach Quebec on this

plateau, and he had been almost baffled. Soon after

his arrival he had taken possession of the Levis

shore and, across the mile of river, had battered

many houses in Quebec to fragments with his cannon.

Still the cliffs remained impregnable. To attack

Quebec from the front promised destruction. On the

French left flank, along the seven miles of the

Beauport shore, lay entrenched the army of Montcalm,

and here successful attack was impossible, as one

attempt, repulsed with heavy loss, had made clear.

At the other side of Quebec attack seemed equally

hopeless. The high cliffs at Cap Rouge could be

easily defended, and Colonel de Bougainville, one of

the best officers in the French army, had been sent

there with some two thousand men to watch every

movement of the British and to concentrate his force

rapidly at any threatened point. In the end Wolfe

had achieved what seemed impossible. By a secret

movement at night he had landed an army at the base

of the cliffs, had climbed the steep path at the

Anse au Foulon, had overpowered the guard which had

been left criminally weak, and at eight o'clock on

September 13 had drawn up his thin red line on the

Plains of Abraham a mile from the walls of Quebec.

Here Montcalm had attacked him promptly on the same

morning and the battle had been fought which meant,

in the long run, the ruin of French power in

America.

This

momentous battle of September 13 was especially

fatal to the leaders on both sides. Not only was

Wolfe killed ; Monckton, his next in command, was

shot through the body and disabled. On the French

side, to the loss of the Commander-in-Chief,

Montcalm, was added that of the

officer next in rank, the Brigadier Senezergues.

.Montcalm realized on his death-bed that in his

defeat was involved the loss of Quebec. One of the

last acts of the dying leader was to write to

Brigadier Townshend, for the time the British

commander, to acknowledge that the surrender of the

fortress must follow. 'Obliged to cede Quebec to

your arms,' Montcalm wrote, 'I have the honour to

entreat your Excellency's kind offices for our sick

and wounded.' Before the next day broke he was dead.

The

Governor of Canada, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, in

whom resided final military and civil authority, was

with Montcalm before Quebec. Though vain and

boastful, he was yet well-meaning and devoted to the

interests of Canada, his native country. To be a

Canadian was in his view to be a member of a

superior race ; a single Canadian, he once wrote to

the Home Government, was a match for from three to

ten Englishmen. Vaudreuil did not lack a certain

bombastic courage, but he inspired no confidence and

was not the man to lead in a crisis. Montcalm's

impulsive, but probably necessary, march to meet

Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham had come so early on

September 13 that the brief battle, little more than

a skirmish, but big with great issues, had been lost

and won before eleven o'clock in the morning.

Vaudreuil had followed the rapid march of Montcalm

from the camp at Beauport. Before he could reach the

field, so fatal to France, crowds of fugitives from

the broken army revealed the ill fortune of the day.

At first Vaudreuil would not believe that all was

lost, and he talked wildly of rallying his Canadians

and of marching up the steep Cote Ste Genevieve to

dispute with the victors their possession of the

Plains of Abraham. Some of the Canadians whom he

sent forward apparently did useful work in checking

the British pursuit of the beaten army. But, for the

time, nothing more could be done. Cadet, one of the

corrupt ring who were making vast fortunes by

robbing New France, besought the Governor not to

risk a second battle. Convinced at length of the

folly of this plan, Vaudreuil took up his position

in an extensive redoubt on the left bank of the St.

Charles River. It was reached from the Quebec side

by a bridge of boats which could be easily destroyed

should the British advance so far. The route from

Quebec was protected in some degree by the cannon of

the town. A boom of logs had been stretched across

the mouth of the St. Charles and the hulks of two

dismantled French frigates lay there in shallow

water. They were armed with cannon which swept the

approaches by water to the bridge.

To

this bridge now came crowding the disorganized

French soldiers, unable to take refuge in Quebec,

because the gates were closed, and anxious to have

the St. Charles River between them and the

victorious foe. The fragments as they arrived

Vaudreuil sent to their old positions at Beauport.

The Chevalier Johnstone, a Scots Jacobite serving

with the French and a close friend of Montcalm,

tells us how he made his way at this time to the

redoubt. He found there at two o'clock in the

afternoon, four hours after the defeat of Montcalm,

'an incredible confusion and disorder; a general

panic and consternation; M. de Vaudreuil listening

to every one, and always to the advice of him who

spoke to him last; not an order given with

reflection or coolness.' Two captains of the

regiment of Beam were shouting out that the redoubt

would be carried in an instant, that they should all

be put to the sword, and that the only thing to do

was to surrender the whole colony at once. Others

were protesting against this course. An alarm was

raised that the ships of the British fleet were

edging in towards the shore. During the panic some

one gave instructions to cut away the bridge of

boats. At the time a considerable part of the French

army was still crowding the road leading from Quebec

and the Royal Roussillon regiment was already on

that side of the bridge waiting to cross. Johnstone

says that he and a colonial officer stopped the

fatuous work of destroying the bridge and drove away

the soldiers who had their axes raised to hew

through the beams. When a council of war met in a

house near the redoubt, Johnstone ventured to enter

the room where seven officers sat with Vaudreuil,

the Governor, and Bigot, the Intendant. The

Intendant was at the table, pen in hand. Johnstone

heard nothing, for Vaudreuil promptly ordered him to

be gone as he had no business there. He went off, he

says, in deep dejection at the loss of Montcalm, and

very tired, but not too tired to stir up some

officers whom he met to protest against surrender.

Various courses were open to the French. They might

stay where they were, rally their strength, and

attack the foe before he could entrench himself or

force Quebec to surrender. A second possibility was

to retire beyond the Jacques Cartier River, thirty

miles above Quebec, where the army would be in touch

with the French ships which had ascended the St.

Lawrence to escape from the British fleet. Here they

might await the arrival of Montcalm's successor, the

Chevalier de Levis, absent at Montreal. Last of all,

the French might accept counsels of despair and end

the struggle by surrendering the colony. Before the

Council met, Vaudreuil had sent a hurried request to

Montcalm for advice and had received a message

naming these three alternatives. Undoubtedly some of

the French officers of the regular army favoured the

surrender of the entire colony and talked openly

before their men in this sense. Vaudreuil declares

that the Chevalier de Montreuil, who had had a long

experience in Canada and was the senior officer

present, insisted upon retreat to Jacques Cartier.

This may well be : Montreuil was an officer who

lacked insight and capacity. It seems that only the

civilians present were for immediate fighting. The

Intendant Bigot warned the officers that, with

winter coming on, it was folly to think of a retreat

that involved the abandonment of the tents and other

needed supplies at Beauport, things which could not

be replaced. He declares that he and Vaudreuil stood

out for attacking the British forthwith, but that

the officers were unanimous against this course.

In

truth the soldiers had no confidence in Vaudreuil as

a leader. During the absence of Levis the young

Colonel de Bougainville ranked next to Vaudreuil,

but he was posted at Cap Rouge and no commander was

present who could speak with authority. It is true

that Bougainville was only a few miles away and that

his opinion might have been secured without much

delay. Some of the officers present were, however,

jealous of this brilliant young friend of Montcalm.

Most of them, while unwilling to fight, were also

unwilling to surrender. Their great fear was lest

the British should cut off the possibility of

retreat up the river towards Montreal. To prevent

this it was quickly decided that immediately after

nightfall the French army should withdraw to Jacques

Cartier. After the council Vaudreuil was full of

bustling activity. He must have kept his secretaries

busy. At half-past four in the afternoon he sent a

dispatch to Levis at Montreal urging him to join the

defeated army at once. To M. de Ramezay, in command

at Quebec, he sent elaborate instructions to

surrender the town rather than to await its capture

by assault, and enclosed a draft of the terms to

ask. At six o'clock, with, as he said, grief in his

heart at the decision to retreat, he sent to the

stricken Montcalm in Quebec a report of what he had

done, courteous regrets at Montcalm's misfortune,

and hopes for his recovery. Thus, even in a moment

of supreme excitement, Vaudreuil forgot none of the

proprieties. But he hated Montcalm; he was glad now

to be rid of him; and soon, to draw blame away from

himself, he wrote a letter to the French Minister of

War full of charges blackening the memory of the

dead leader: ' If I had been sole master, Quebec

would still have been in the King's hands.' About

ten o'clock on the night of the battle, when

Vaudreuil had already fled, Montcalm sent a message

approving of what he had done and of the terms

proposed for the surrender of Quebec. Both leaders

thus agreed that the fortress must yield.

Vaudreuil and his officers now lost their heads in

their deadly fear lest the British should occupy the

lines of retreat towards Montreal and divide the

French forces in Canada into two parts. The

situation of the French was by no means hopeless.

Between the Beauport camp and the victorious British

lay a considerable river, fordable only at one place

and at low tide ; a little west of the Plains of

Abraham, at Cap Rouge, was Bougainville with between

two and three thousand men in an excellent position

to attack the enemy in the rear; in Quebec itself

were as many more men capable of bearing arms and of

aiding the troops from Beauport to attack the

British front. The French could, indeed, rally

something like 10,000 men. But confidence in

Vaudreuil as a soldier was impossible; no commanding

personality was there to weld together the scattered

fragments of this discouraged host; and, lacking

direction, it fled.

Soon

after nightfall the retreat from Beauport began.

Orders were given that the army should break into

three divisions and that each division should retire

as silently as possible so that the British might

not become aware of the retreat. There was grave

mismanagement somewhere. Poulariez, the officer

commanding the eastern wing of the army at

Montmorency, was left without instructions. After

long waiting, he sent to Vaudreuil's head-quarters,

only to find that the Governor had run away and that

he himself was left to follow as best he could. The

French marched by way of Charlesbourg and Old

Lorette. It unfortunately happened that brandy was

served out to the soldiers, and this heped to ^pmoy

any semblance of order in the retreat. 'This was

not', says the Chevalier Johnstone, 'a retreat, but

a flight the most abominable; a rout even a thousand

times worse than that of the morning on the Heights

of Abraham, and with so much confusion and disorder

that, if the English had known it, it would not have

required more than three hundred men to cut in

pieces our whole army. Except the Royal Regiment of

Roussillon, which M. Poulariez kept ... in order, I

did not see thirty men of any one regiment together;

all the troops mixed and interspersed and every one

running as fast as his legs could carry him as if

the enemy were pursuing them close at their heels.'

Daine, another French observer, says: 'No rout was

ever more complete than that of our army. Posterity

will hardly believe it.' Not only the Canadian

militia but even some of the regulars were so

panic-stricken that, after calling for refreshments

at the houses of the farmers, they rushed off, too

fearful of pursuit to partake of what was brought.

French Canadian peasants told the British at a later

time that in the retreat Vaudreuil and the officers

took no thought for their men, but went off in such

haste that they ' flew through the air like a cannon

ball'. Though a great part of the army was without

food, Vaudreuil took good care that needed supplies

and excellent cooks should accompany him on the

retreat. Apart from a little ammunition and some

tents and camp kettles, the French abandoned their

cannon, munitions of war, provisions, and baggage.

Since there were few, if any, wagons, not even a

barrel of powder could be taken. Officers and men

alike lost their personal effects.

At

daybreak on the morning of the 14th, Bougainville,

now at Lorette, was first made aware of the retreat

of the French. By that time the whole host had swept

past, panic-stricken and convinced that it would be

safe only beyond the river at Jacques Cartier. That

evening, after a long and weary march, the fugitives

reached Pointe aux Trembles and there rested. By

daybreak of the 15th they were again in motion. When

they reached the Jacques Cartier River they found

the bridge broken down. The army was intent on

putting the river between itself and pursuit. It

managed somehow to cross and that night the weary

men were lodged in the barns on the right bank. They

were now thirty miles from Quebec and, for the time

at least, safe.

Meanwhile, neither in Quebec nor in the British army

had the retreat become known. Before leaving, the

French had broken down the bridge across the St.

Charles so that the British might not cross easily

to the Beauport side. The tents at Beauport remained

standing and the British thought that they were

still occupied. The British were themselves busy in

making sure of their own defences before Quebec. Two

days after the battle a French officer visited the

abandoned camp, found it undisturbed, and, to the

alarm of the British, fired off some cannon that

stood ready charged. Ramezay, shut up in Quebec,

sadly needed the provisions left at Beauport and

could easily have secured them; but he was not

notified of the French retreat, and in the end the

provisions were carried off by the starving

habitants and by the Indians.

The

French hopes now rested in the successor of

Montcalm, the Chevalier de Levis. This leader of a

lost cause was a member of a French family so

ancient that it claimed descent from the tribe of

Levi and cousinship with the Virgin Mary. There was

a picture in the Chateau of Levis in which a member

of the family was represented as addressing the

Virgin as his cousin. The Chevalier was himself

destined to win new lustre for the family by the

high position to which in later years he attained as

Duke and Marshall of Franco. Montcalm had said of

him that, while a man of routine and not very able,

he was practical, sensible, and alert, with an

admirable capacity to think for himself when thrown

on his own resources. During many days while the

French had steadily baffled Wolfe's plans, Montcalm

and Levis had been constantly together, except when

the tireless energy of Levis had worn out Montcalm.

Later, with great regret, Montcalm had been obliged

to part with Levis and to send him to secure the

approaches to Montreal from the south and the west.

Thus Levis had not fought in the memorable battle of

September 13. But the evil tidings reached him

quickly. At six o'clock on the morning of the 15th a

courier arrived at Montreal with the news of the

defeat. At nine o'clock Levis was on his way to

Quebec. He received on the road a letter from the

Chevalier de Montreuil, an old companion in arms,

begging him to use all diligence and saying that he

alone could save the situation. In spite of a storm

and of bad roads he made rapid progress. When he

arrived at Jacques Cartier on September 17 there was

joy in the French camp. It was, however, with bitter

rage that Levis saw on all sides the evidence of

incompetence. Panic had spread everywhere. Officers

and men were alike disorganized. 'I never saw

anything like it,' Levis wrote, ' absolutely

everything— tents, kettles, and all their equipment,

they had left behind at Beauport.' Many Canadians

had deserted and, in disgust, the Indian allies of

the French had already set out on the return journey

to their villages.

The

task of Levis was assuredly a grave one. He strongly

condemned the retreat to Jacques Cartier. But Quebec

still held out, and, at all hazards, he said, its

loss must be prevented ; rather than surrender the

fortress to the English, the defenders should

destroy it and thus leave the enemy no stronghold in

which to pass the winter. The first task of the

defeated army was thus to rescue Quebec, and Levis

gave orders at once that the march back should

begin. Vaudreuil had always been on friendly terms

with Levis and now he was all acquiescence. 'As soon

as the Chevalier de Levis arrived,' he wrote on

October 5 to the French Minister of War, 'I

conferred with him and was charmed to see him

disposed to lead the army back towards Quebec.'

Bougainville still kept a guard at Cap Rouge and Old

Lorette; he had not joined the flight of Vaudreuil

and now stood between him and pursuit. Levis and

Vaudreuil quickly sent messages to Quebec cancelling

the instructions to surrender. Bigot, all energy in

carrying out a plan of which he thoroughly approved,

undertook to get supplies of food into Quebec. One

plan was to send them down by way of the river. He

had done this often before, in spite of the presence

of the British fleet, and he could do it again.

Moreover a route by land was still open. The French

had a depot of provisions at Charlesbourg, and,

since the British had not yet occupied the camp at

Beauport, the path to Quebec was clear. As a matter

of fact, provisions reached Quebec on the evening of

the 17th by both these routes.

All

this time, however, the British were showing great

vigour. Townshend, now in command, had made it his

first duty to strengthen his own camp, and by five

o'clock on the day of the battle he had

entrenchments five feet high on the Plains of

Abraham. Late that night he occupied the General

Hospital on the banks of the St. Charles River,

crowded now with from twelve hundred to fifteen

hundred of the wounded of both sides. On the 14th

both sides agreed to a short truce for the burial of

the dead. The season was late; the fleet must soon

depart or be caught in the ice; and the British well

understood that not a moment was to be lost in

taking Quebec. 'The utmost diligence', says Admiral

Holmes, 'was used and the greatest fatigue

undergone, with Spirit and Cheerfulness by every

Body, to bring the Campaign soon to an End.' Two

thousand men were already busy making fascines and

gabions to protect an approach to the walls. By the

evening of the 13th, many of the trees on the Plains

of Abraham likely to protect an assailant had been

cut down, and the houses near the British camp had

all been fortified. On that night the British slept

within a thousand yards of the walls of Quebec. In a

few days most of the underwood within a mile of

their flank and rear had been cleared away. For a

day or two they were aided by fine weather. They

used the steep road from the strand of the river up

to the heights at the Anse au Foulon, henceforth to

be called Wolfe's Cove, for drawing artillery and

ammunition to the Plains of Abraham. This toilsome

task was carried on with much energy. Sailors as

well as soldiers showed great alacrity ; in this

work on land the word of command was given as on

board ship: 'It was really diverting', says an

eyewitness who saw the men toiling up the hill, 'to

hear the midshipmen cry out "Starboard, starboard,

my brave — boys "

Tragedy meanwhile hovered over Quebec. Montcalm died

early on the morning of the 14th, content, as he

said, to leave the military command in the hands of

Levis, whose talents and capacity he had always

valued. Vaudreuil had agreed that Quebec must

surrender ; so also had Montcalm ; and its defenders

could claim the warrant of both leaders for such an

act. Naturally they now had deep searching of heart.

For a day or two Ramezay kept up the appearance of a

resolution to hold the place. His shot and shell

greatly annoyed the British on the Plains of Abraham

and forced them on the 15th to change their line of

encampment ; even after this, British batteries on

the south side of the river, more than a mile away,

were disturbed by Ramezay's ceaseless fire, as were

also the boats carrying munitions of war from the

Point of Levy to Wolfe's Cove. There was, however,

no heart in the defence of Quebec. Disorder and riot

soon broke out. Those within the town had not

realized at first that now they were left to their

own devices. Across the basin they could see the

white tents of the French at Beauport, and since, as

they supposed, the French army was still there,

rescue seemed not impossible. Disillusion came with

the news of the headlong flight to Jacques Cartier

and not unnaturally it produced a panic.

The

Chevalier de Ramezay, who commanded at Quebec, was a

Canadian by birth and had spent his whole life in

the service of the colony. He was the fifteenth

child of Claude de Ramezay, who had been Governor of

Montreal. Three of his brothers had perished in the

service of the French King. As early as in 1720

Ramezay had attained the rank of ensign. Later he

had seen almost every variety of service in the

country. Since he was only a colonial officer he was

rather despised by the officers from France. One of

these, Joannes, town-major of Quebec, declares, for

instance, that, as Ramezay had only known rough

backwoods fighting, he had no conception of the

proper way to defend a fortress. The Governor,

Vaudreuil, a fellow Canadian, did not like Ramezay

and had mortified him by putting another officer,

the Chevalier de Bernetz, in command of the Lower

Town. The courage of Ramezay is not, however, to be

doubted. Now, face to face with a difficult problem,

he required both courage and wisdom. Even though

Montcalm and Vaudreuil had admitted that the

fortress must surrender and had outlined the terms

to be demanded, it was for Ramezay himself to decide

when the moment to yield should come. As Montcalm

lay dying Ramezay went to him for orders. The

stricken leader was, however, resolved to leave such

decisions to those who should survive to see the

future. His time was short, he said, and he had

business to attend to of more moment than the

affairs of a ruined colony.

As, a

few months later, the British themselves found, to

defend Quebec against assault would not be easy. The

French Government had always shrunk from the great

cost of proper fortifications, and the strength of

Quebec was due less to what man had done than to

natural position. It had been hitherto immune from

assault only because of the difficulty of scaling

the steep heights rising from the river, but now

these heights had been gained by a triumphant foe.

Montcalm himself had called ridiculous the defences

on the landward side before which the British were

entrenched. The wall, not yet really finished, which

confronted the British encamped on the Plains of

Abraham, was commanded by high ground only a few

hundred yards away. It was better fitted for defence

against muskets and bows and arrows than against

artillery. For fear of shaking the rest of the

fortifications, the French engineers had not used

the necessary explosives to make excavations in the

rock. There was thus no ditch. There were no

outworks. The walls, if bombarded by the powerful

batteries which the British were erecting, could

probably not resist a cannonade for two hours. To

meet attack from this side the defenders had not a

single battery capable of action.

The

town itself was a ruin. The Lower Town, curving for

a mile or two along the strand of the river and

inhabited by the traders and poorer classes, was a

dismal sight. No less than five hundred and

thirty-five houses had been burned, hardly a dozen

remained standing, and some of the narrow streets

were impassable owing to the debris caused by the

British bombardment. The part of the city known as

the Upper Town, where dwelt the Governor, the Bishop

and other ecclesiastics, and the leading citizens,

had fared somewhat better. Its principal buildings

were, however, in ruins. The Governor's

residence—the Castle of St. Louis the Bishop's

palace the Cathedral, Marchalls' College, had all

been in range of cannon on the opposite shore, and,

of the first three, at least, the British batteries

had left little but the walls. In the Seminary, a

college for the training of priests, standing near

the Cathedral, only the kitchen was left, and here

the Cure of Quebec was living as best he could.

Wolfe's guns had dismounted some batteries in the

Upper Town and these were now filled with debris.

Even walls six feet thick had not withstood his

furious bombardment.

After

the defeat of the 13th of September Ramezay had

asked that a French engineer should be sent into

Quebec to help him make the best of its shattered

defences; but the disorganized leaders had not

heeded the request. During the siege no stores of

provisions had been kept in Quebec, because of the

danger from the British fire. Supplies had been

brought daily from the camp at Beauport and from the

surrounding country. No doubt there was food in

private houses, but most of it was now kept

concealed by the owners. With supplies for only a

few days in sight, Quebec seemed on the verge of

starvation. There were a good many mouths to feed.

Among the civilians were two thousand seven hundred

women and children and a host of clerks, workmen,

and domestic servants. The French, too, must feed

their many invalids at the General Hospital. In

addition to these were the forces in the town,

numbering perhaps two thousand six hundred. About

eleven hundred and fifty were regular soldiers; the

rest were untrained militia—peasants, mechanics, and

merchants.

As

early as on the morning of the 14th the citizens of

Quebec held a meeting to consider their position.

Headed by the Mayor, they then entreated Ramezay to

surrender. They had been prepared, they said, to

face the loss of their homes and their property.

During the prolonged bombardment they had not

murmured. Now, however, the British had won a signal

victory. Quebec, face to face with famine, could no

longer be defended. Under the rules of war, if

Ramezay should wait till it was taken by assault,

not only men but helpless women and children would

be put to the sword. Some there were who opposed

these views and declared that the citizens of Quebec

seemed more anxious to save their goods than their

country. But the wish to surrender was not confined

to unarmed citizens. Many of the Canadian militia,

an amateur soldiery, were fearful that, if found

fighting, they would be treated with the rigour

meted out, under the rules of war, to civilians in

arms; or that, if treated as soldiers, they would,

upon surrender, be transported to France. They now

declared that they would no longer serve and that

they looked upon themselves as civilians only. When

the drums beat for muster they refused to take their

places, much to the wrath of the officers of the

regular service. They abandoned even the exposed

posts of which they had charge. A French officer,

enraged, proposed to fall upon them sword in hand;

but menaces, promises, even the experiment of

serving out brandy, failed to inspire them with

courage. They deserted in bands. Flight by way of

Beauport was still possible. Within a day or two

some nine hundred had gone off, a few to the

British, but most of them to find refuge with the

inhabitants of the surrounding country. The spirit

of the men in the regular force was nearly as bad

and it was soon apparent that even the officers were

almost unanimous in desiring surrender.

What

was Ramezay to do? On the 15th of September he

called a council of war. By this time Vaudreuil's

flight to Jacques Cartier had become known to all.

At the council of war Ramezay read the instructions

in regard to surrender which he had received from

Vaudreuil ; he made also a statement as to the

famine imminent in the town. Then he asked each

officer, with these naked facts before him, to give

in writings independent view of what should be done.

Fifteen officers were present and we have still the

record, solemnly made, of each man's opinion. For

continuing the fight one officer alone stood out.

The Captain of the town artillery, M. Jacquot de

Fiedmont, who had elsewhere shown conspicuous

courage, wrote his advice ' to put the garrison on

still shorter rations and push the defence to the

last extremity '. All the others, however, advised

an opposite course, and the council of war decided

that the best thing to be hoped for was an

honourable surrender, and that, should there be

delay, even this might not be possible. The hapless

commander, with whom rested the final word, may well

have been perplexed as to his duty. Ill health did

not make his burden lighter. On the 15th he asked

permission from the British to send the women and

children past their lines, but the request met with

a stern refusal.1 His foe would not allow him to be

relieved even of this difficulty.

Scarcity of provisions caused the most serious

problem. Since the French tents were still standing

at Beauport, Ramezay sent thither, hoping to find

provisions ; but, as we have seen, the inhabitants

and the Indians had already made help from this

quarter impossible. What portion of the abandoned

supplies they could not carry off they had wasted,

and Ramezay's messengers found strewn about in the

wildest disorder flour and other stores that might

have saved Quebec. Just at this time came one gleam

of hope. News arrived from the defeated French army.

A letter from Vaudreuil, which must have been

written during his wild retreat, reached Ramezay

with the tidings that he was sending into Quebec

both provisions and troops.

The

hapless commander in Quebec had to ask himself if

such a promise could be fulfilled. He said nothing

about the letter but, in order to get more light,

sent out two officers, Joannes, of the French

regular service, and Magnan, of the Canadian

militia, to learn for themselves what the prospect

of succour by the panic-stricken French army really

was, and, if possible, to see Vaudreuil in person.

By this time, however, the Governor was far away.

Joannes pledged himself to go out and return in a

single night, that of the 15th. He went some nine or

ten miles towards Jacques Cartier; and then sent

forward an urgent letter to Vaudreuil to say that

there was a bad state of feeling in Quebec and that,

if no word was received from him by ten o'clock on

the morning of the 17th, negotiations for surrender

would be opened. What Joannes saw and heard, perhaps

from Bougainville at Lorette, led him to believe

that rescue was by no means impossible, and he

returned to Quebec convinced that the defenders

should hold out. In this he was supported by the

brave Fiedmont. But Ramezay was of stuff less stern.

Levis had not yet arrived at Jacques Cartier and a

distressing account of the lack of discipline and

order in the French army had reached Ramezay. Help

from such a force was, he thought, hardly to be

expected. By this time, indeed, he had decided to

give up the fight. Vaudreuil charges that Ramezay

reached this decision without having informed

himself of the conditions in Quebec, and declares

that there were cattle and horses in the town which

would have prevented famine.

It

must be said that Ramezay had no good reason to

believe that the demoralized French army could now

render effective help. It is, of course, easy to

suggest what he might have done, but from one urgent

fact he could not escape ;— about him were women and

children now in panic fear and clamorous for food.

Vaudreuil had instructed him not to hold out until

the British should assault Quebec. Now, because the

foe had worked with fiery energy, this assault was

imminent. By the morning of the 17th the British had

a hundred and eighteen guns mounted in their

batteries and were almost ready to open fire upon

the feeble walls. Just at this time, too, the

line-of-battle ships shifted to a position nearer

the town and prepared for a bombardment. A renewed

panic followed in Quebec. Ramezay himself describes

his situation :

'It

was no longer possible for me to hold any post

securely. The batteries had been abandoned and the

weak points were no longer guarded. I had not

officers enough to carry out my orders ; I could no

longer count upon the militia officers since the

request [to surrender] which they had made. My

situation soon became only too clear. On the 17th .

. . there was an alarm, and I learned that an

English force was coming in small boats to land in

the lower town. At the same time we saw all the

war-ships get under sail to come nearer the shore. A

strong English column advanced [by land] towards the

Palace gate where the entrance was unguarded. I

ordered a general alarm and every man to take his

place. While I was in the square with several

officers, an officer whom I had sent to carry out my

orders returned to tell me that none of the militia

would fight. At the same moment the militia officers

came to me. They said that they were in no temper to

sustain an assault; that they well knew I had orders

to the contrary; and that they intended to replace

their weapons in the armoury, so that, when the

enemy entered Quebec, the militia should be found

without arms and should not be put to the sword.

Henceforth, they said, they should regard

themselves, not as soldiers but as civilians. If the

army had not abandoned them they would have

continued to show the same devotion that they had

shown throughout the siege ; now, however, with no

further resources left, they did not feel obliged to

face a useless massacre ; such a sacrifice would not

delay by one hour the taking of the town. All this

time the enemy drew nearer and my situation was

cruel. I took the opinion of several officers near

me, and, in particular, that of my second in

command, the Chevalier de Bernetz. By their advice I

raised the flag, according to the orders I had

received, and sent to the enemy's camp M. de Joannes,

aide-major, with the terms of capitulation which M.

de Vaudreuil had sent to me.'

Not

only the militia had fallen into a state of abject

terror. ' To my great regret' says the French

officer, Bernetz, 'I saw this same unhappy spirit

working in the hearts of the regular soldiers. I

shed tears of grief over it.' He mourns, indeed,

that he had not been killed earlier in the campaign,

instead of living to see this final humiliation.

At

three o'clock on the afternoon of the 17th, in

pouring rain, Joannes, despite his vigorous protests

against surrender, was sent to the British general

to ask for terms. Townshend and Admiral Saunders

took counsel together, made moderate demands, and

gave Ramezay the four hours from seven to eleven

o'clock of that night for consideration. Joannes had

secured as long a time as possible, in order to

increase the chance of rescue, and now he and

Fiedmont, on their knees even, entreated Ramezay not

to yield. They begged him, if he could do no more,

to evacuate the Lower Town and concentrate his force

in the Upper Town, where he would be almost safe

from the fire of the British ships. It was too late;

Ramezay's spirit was gone. His forces were utterly

discouraged. Wholesale desertion was taking place

and starvation seemed imminent. The heavy rain added

to the discouragement, for it would retard any

rescuing movement. Ramezay reasoned, moreover, that

even if the British were in Quebec, they would still

be as vulnerable there as in their fortified post on

the Plains of Abraham. In fact, when seven months

later the French attacked Quebec, the British

preferred to fight on the open plain.

A

little before eleven o'clock at night, Joannes was

sent out again to the British camp with a final

acceptance of the terms offered, terms, it should be

noted, better than those which Vaudreuil had told

Ramezay to accept. Each side was to take a hostage

from the other in pledge of good faith. While this

arrangement was being carried out a singular thing

happened. Ere the dejected Joannes had left Quebec

to return to the British head-quarters with the

final surrender, help reached Quebec. A force of

fifty mounted men, under Captain de la Rochebeaucour,

sent by Bougainville, entered the town from the side

towards Beauport, and brought with them some sacks

of provisions and the news that other supplies were

coming by water and that rescue was near. When

Ramezay had signed the capitulation he had not been

aware of La Rochebeaucour's arrival. This brave

officer now went to Ramezay and, like others, begged

on his knees for delay. Whether, had Ramezay known

sooner of this succour, he would have drawn back,

and whether within the next few days France and

England would again have grappled in deadly strife

on the Plains of Abraham, who can say? The help had

come too late. Ramezay had already signed the

capitulation and would not draw back. La

Rochebeaucour rode off, carrying with him some of

the provisions that he had brought for the relief of

Quebec and bitterly angry at the conduct of Ramezay.

There

is no doubt that, had the surrender been delayed

even another day, the British would have been in a

dangerous situation. Levis was marching back to

Quebec with an army that trusted him as a leader,

and the British had good reason to be nervous about

their position. They were thus eager to enter the

town. The weather, which had been delightful for a

day or two after the battle, was now cold and wet.

Rain had made the roads so bad that only with

difficulty could the troops drag up further

artillery to the Plains of Abraham. It was desirable

that the British should occupy Quebec before it was

further injured by bombardment, for they might have

to find winter quarters there. Accordingly they were

ready to grant easy terms. On one thing only were

they unbending : the garrison in Quebec should not

serve longer in Canada. When Ramezay asked leave to

join the French army under Levis, Townshend's answer

was that all but the militia must be embarked at

once for France. The British agreed that the

garrison, bearing arms, with drums beating and

matches lighted, should march to the ships with the

honours of war; they agreed further to respect

private property, to leave the inhabitants of Quebec

undisturbed in their houses, and to permit the free

exercise of the Roman Catholic faith, until this

question should be finally determined by a treaty of

peace.

These

arrangements were completed on the 18th. Then the

grenadiers, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Murray,

took possession of the gates of the Upper Town. At

the same time a naval force, under Captain,

afterwards Sir Hugh, Palliser, occupied the Lower

Town. On the Grand Parade, with all the pomp of war,

Townshend himself received the keys of the fortress

from its former masters and the British flag was

raised over Quebec. The French garrison which

marched out made a brave showing and left only a

ruined city to their foes. Since the day of the

battle the numbers in the French ranks had declined

; now rather less than two thousand men, of whom

more than nine hundred were militia, surrendered.

All but the militia were to be taken at once to

France.

The

fatal intelligence of the surrender of Quebec

reached Bougainville when he was less than two miles

away. Levis heard it near Cap Rouge, less than ten

miles from Quebec, when his army had already covered

the greater part of the return march. 'The news,' he

writes, 'which rendered useless all that I had done,

affected me infinitely. It is unheard of that a

place should surrender which had been neither

attacked nor invested.' Bourlamaque, in command at

Isle aux Noix, wrote that the blow was

incomprehensible, terrible. The fall of the fortress

meant, indeed, as time was to show, the loss to

France of an empire.

The;

surrender of Quebec caused in the French army the

natural and stern resolve that before spring came

they would recapture the fortress. To this

everything else must give way. Levis would have

wished to close in at once on Quebec and to harass

the victors without delay. For this task, however,

his resources were slender. He had no artillery and

but little ammunition. Even food he could get only

with great difficulty. Wolfe's cruel policy of

desolating the parishes was now justified ; the

country about Quebec could not support an attacking

army. Levis soon resolved that for the moment a

siege was impossible. To be safe from attack, he

decided to return to Jacques Cartier, whither the

French had fled so precipitately on the night of the

13th. With the river of that name as his frontal

defence against a further British advance, he could

make plans in some security.

Once

more, therefore, in bad weather and over roads heavy

with recent rains, the discouraged and defeated

French army dragged itself away from Quebec. By the

24th of September the second retreat was completed

and many of the French soldiers, turning their

swords into pruning-hooks, were helping the Canadian

farmers to reap the scanty harvest. A high bluff on

the right bank of the Jacques Cartier River, where

it joins the St. Lawrence, furnished a site little

inferior to that of Quebec for a fort. The French

leaders were quickly busy with plans. By September

26 engineers had begun to lay out new works. In the

end, the works proved so strong that, as a matter of

fact, Jacques Cartier was the last point on the St.

Lawrence where the French flag was lowered.

For

the time, however, little more could be done. The

foraging parties could secure little, and famine was

imminent. When, on October 4, some Canadians brought

in twenty cattle which they had secured in the

neighbourhood of Quebec, the rejoicing was great

over what proved, after all, but a mouthful for so

considerable an army. Levis sent to the French

frigates still lying in the river some distance

above Quebec to ask for food, but his boats returned

empty. By October 15 the army at Jacques Cartier had

in sight provisions for only nine days. With such

scant resources it was impossible to keep a great

force at that point. The French quickly found that

they could not hold together their Indian allies,

unless they could supply them with food. Since this

was impossible, the Indians soon scattered to their

own villages. For the moment at least Quebec was

safe in the possession of its new owners.

With

the fall of Quebec the outlook for France in North

America was indeed gloomy. She had made magnificent

claims to hold the vast region stretching from the

mouth of the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the

Mississippi. From the early days of discovery the

sons of France, more imaginative than their English

rivals, had been haunted by the mystery of the

interior. While the English had rarely ventured far

from the sea-coast, the French pioneers had pressed

inland. Champlain had reached the Great Lakes ; La

Salle had linked the St. Lawrence with the

Mississippi in his dream of a far-reaching French

Empire ; La Verendrye had gone still farther afield

and had penetrated to the foothills of the Rocky

Mountains. Fur-traders had followed the explorers.

To this day, in regions far remote, regions which

have passed to another race, French geographical

names and some lingering remnants of French speech

often furnish a reminder of the far-reaching

energies of the explorers and traders of New France.

To assert her claim and to protect the richest

fur-trade in the world, France had built forts at

the chief points of vantage. At the forks of the

Ohio, commanding the commerce of that river, the

fleurs-de-lis had waved over Fort Duquesne. At

Niagara, commanding the passage from Lake Ontario to

Lake Erie, stood another French stronghold. Fort

Frontenac commanded the point where Lake Ontario

narrows into the River St. Lawrence. These were the

chief forts, but at many other places, even in the

far west on the Red River and beyond it, the energy

of France was represented by posts, where her

traders gathered the harvest of furs from half a

continent.

"Now,

however, this fabric which France had reared was

tumbling down. One by one the British had mastered

the vantage points. The summer of 1758 had been

disastrous to the outposts of France. With the fall

of Louisbourg in July she was stripped of power east

of Quebec. At the end of August in that year the

British had captured Fort Frontenac at the head of

the St. Lawrence and cut off communications between

Quebec and the West. A little later, in bleak

November, they had struck a vigorous blow on the

Ohio, captured Fort Duquesne, and were now rearing

in its place Fort Pitt, named after the great

minister. Niagara had still held out defiantly, but

in the summer of 1759 it too had fallen. Thus,

except at a few scattered points where surrender

must come whenever the British should demand it, the

whole power of France in the interior had fallen.

After the disaster at Quebec, only the central

region about Montreal remained to her.

This

place was now the point of danger. Vaudreuil, though

vain and bombastic, was not a coward, and he soon

resolved to take up his head-quarters in Montreal.

Accordingly, on September 28, he issued a pompous

ordinance placing Levis in command 011 the lower

river, and then set out from Jacques Cartier. On the

first of October he arrived in Montreal, in company

with the Bishop of Quebec, and was soon planning

with feverish energy to meet the expected attack on

this last foothold of France in Canada.

It

seemed possible that Montreal might be won by the

British befpre winter set in. It was menaced from

the west and from the south. At Oswego, near the

point where

the

St. Licence River flows out of Lake Ontario, General

Gage had gathered an army to descend the river to

Montreal. His path was not clear, for the French had

a fort called La Galette at La Presentation, some

seventy miles down the river from Oswego, at a point

commanding the St. Lawrence and near the Mohawk

Valley, leading to the heart of the colony of New

York. The fort was a centre from which the Indians

in alliance with the French had made numerous forays

and caused much trouble. Its defences were, however,

weak and Gage could easily have overpowered it. It

was not this problem but another which chiefly

troubled him. If he descended to La Galette, could

he winter his force there, in case it was impossible

to advance to Montreal? If Gage had known what was

happening at Quebec, he would probably have made a

start for Montreal. Communications in this campaign

were, however, extremely difficult. It is actually

true that the news of the fall of Quebec reached

England, three thousand miles away, on October 16

and did not reach General Amherst, who was on Lake

Champlain, less than two hundred miles away, until

October 18. Gage heard nothing of it for a long

time, and in the end, ' to my great concern,' says

his superior officer, Amherst, decided not to make

any advance towards Montreal during that season. In

slow deliberation he was more than a rival of his

chief.

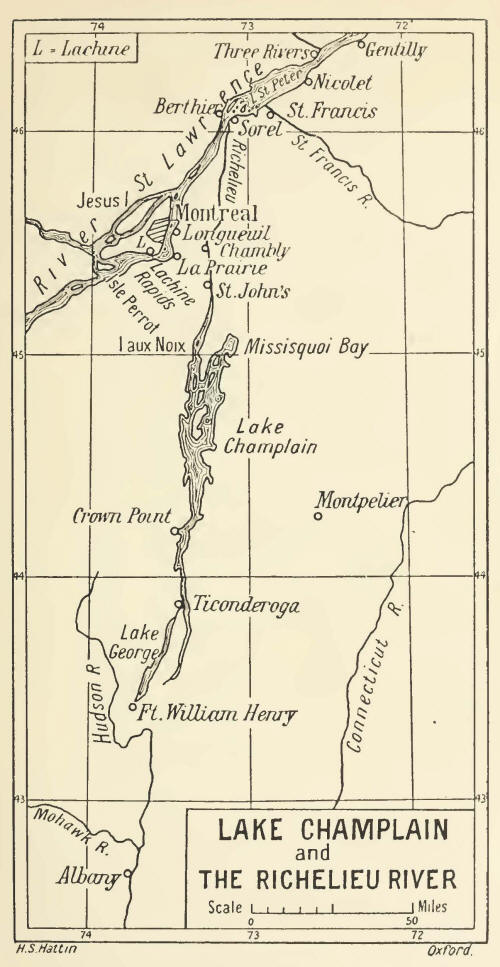

Amherst himself was approaching Montreal from the

south along the war-worn route by Lake George and

Lake Champlain. It had been hitherto a line of

advance fatal to British arms. In 1757 Montcalm had

captured a British army at Fort William Henry at the

foot of Lake George. In the next year at Ticonderoga

Montcalm had again inflicted a bloody defeat on the

British trying to advance by this route into Canada.

Now Amherst himself, the Commander-in-Chief, was

using it for his advance. He had set out from Fort

William Henry at the south end of the lake on July

21, 1759. The French did not try to check his

progress up Lake George and Lake Champlain.

Ticonderoga, where the British had been beaten with

such heavy loss in the previous year, the French

blew up at Amherst's advance ; Crown Point, on Lake

Champlain, they also abandoned. All this had been

done by August 1, and it was the news of these

successes which had led to an outburst of rejoicing

in England and to the humorous suggestion by Horace

Walpole that Amherst should be given the title of

Ticonderogious. But, having done so much in the face

of a fleeing enemy, Amherst paused to make sure of

his ground. At Crown Point he found what he thought

the best situation in America for a fort, and he

decided to build there a massive structure which

might defy the enemies of Britain for all time. Soon

he had three thousand men engaged in the task. He

worked with untiring energy and all that he did was

good. But during these weeks after August 1 the

crisis of Wolfe's attack on Quebec had come, and the

appearance of Amherst on the St. Lawrence would have

been of inestimable service to the despairing

British leader. Help did not appear. What Wolfe

achieved, he achieved alone; Amherst gave him no

aid.

Without doubt Amherst was an efficient officer. '

There does not exist', wrote General Yorke in this

year, of Amherst, 'a worthier nor a more modest man

than that nor a plainer or better soldier.'

But, he added, 'Wolfe has more fire,' and this

difference really explains the slow policy of

Amherst. He would run no risks. Even at the cost of

much time, he must be secure in every step he took.

To himself the reasons for not advancing at once

from Crown Point were all-sufficient. His scouts

reported that the French had three or four armed

vessels on the lake. To take forward his army and

its equipment by land was impossible because of bad

roads and of the danger of ambush in the forest ;

and he could not take it by w^r in small boats

unless he was able to drive off the armed ships of

the French. He paused, accordingly, to build the

necessary vessels and a floating battery.

The

military task before him was formidable. Montcalm

had sent one of his best officers, Bourlamaque, to

guard this route. With Bourlamaque were now about

thirty-five hundred men in a strong position. Lake

Champlain discharges its waters into the Richelieu

River. A few miles after leaving Lake Champlain this

river is divided by an island which the French

called Isle aux Noix. On this island they had built

a strong fort. Its cannon swept the approaches by

way of the river. To reach the St. Lawrence Amherst

must pass this fort. If he attacked it from the

water, the French cannon could demolish his small

vessels. If he advanced to the attack with a land

force, he would find the island fort protected on

all sides by the river.

Amherst's problem had been made more difficult by

lack of communication with the British before

Quebec. Hardly any news trickled through the French

lines. As early as August 7 Amherst had sent a

letter to Wolfe by way of Nova Scotia and the

Kennebec River. Since it would be long in arriving,

he had made next day a more direct attempt. He sent

Captain Kennedy, a kinsman of General Murray, with

some companions to go through the forest to the St.

Lawrence by way of the Indian settlements on the

south shore. If Kennedy encountered Indians he was

to promise them a liberal reward for bringing him to

General Wolfe. Kennedy encountered the Indians of

St. Francis, but, instead of honouring his flag of

truce and acting as friendly guides, they treated

him and his party as spies, put them in irons, and

carried them to the French. The first news that

reached Amherst came on September 10 in the form of

a letter from Montcalm saying that they were his

prisoners.

The

conduct of the St. Francis Indians to Captain

Kennedy brought to a head the resolve of the British

to punish these savages. There was not only this but

an older score to settle with them. For well nigh a

century they had been a terror to the people of New

England and had carried on murderous warfare against

the helpless frontier settlements. Amherst now

authorized a party of two hundred and twenty picked

men, called in frontier warfare ' Rangers ', under a

well-known leader, Major Rogers, to go by forest

pathways to the head-quarters of the savages and

inflict on them summary punishment.

The

expedition set out on September 13, the very day of

Wolfe's great victory. 'Take your revenge' wrote

Amherst, 'but don't forget that though these

villains have dastardly and promiscuously murdered

the women and children of all ages, it is my orders

that no women or children are killed or hurt.' We

have Rogers's own account of what he did. In some

way the intrepid ranger managed to get past the

French armed vessels patrolling Lake Champlain. He

hid his boats on the shores of its northern inlet,

Mississquoi Bay, left two friendly Indians on watch,

and then began a long and painful march through the

forest. His goal, St. Francis, was distant a march

of many days. When Rogers had been out two days,

friendly Indians warned him that a strong party of

the enemy had found his boats and was pursuing him.

Bourlamaque, at Isle aux Noix, had in fact discerned

the purpose of the expedition and had sent a warning

to the priest at St. Francis—a warning apparently

not heeded. Rogers pushed forward, hoping to

outdistance his pursuers, who moved leisurely, since

they thought they should catch him on his return

journey. On the tenth day of a toilsome progress

through wet spruce bog, where the water was usually

about a foot deep and where the men could be dry at

night only by swinging themselves in hammocks made

of the branches of trees, he readied the River St.

Francis about fifteen miles above the village. Since

the village lay on the opposite bank of the river,

it was necessary to cross. At the ford the water was

five feet deep and the current very swift. Rogers

put the tallest of his men up stream and, by holding

on to each other, they crossed over with the loss of

only a few muskets. The force had now good dry

ground on which to march and it crept towards the

village. When three miles distant, Rogers halted his

party and climbed a tree, to take his bearings.

Then, in the early evening, he and Lieutenant Turner

and Ensign Avery went farther forward to reconnoitre.

They

found the Indians engaged in a dance. Rogers drew

his force nearer to the village until, at three

o'clock in the morning, he was distant but five

hundred yards. By this time the noisy festivities

were over and the quiet of night and of sleep had

settled down upon the savages. At half an hour

before sunrise the signal for attack was given. The

savages had no time to take arms in defence and an

appalling massacre followed. With the exception of

three houses, where was stored corn which Rogers

reserved for the use of his party, all the houses

were soon on fire. Many Indians who had concealed

themselves in the cellars and lofts of their houses

were burned to death. Others who tried to get away

in canoes were either shot or died by drowning.

Among those who thus perished was the priest. By

seven o'clock in the morning the grim work was

completed. Some two hundred Indians had been killed,

including, it should seem, a good many women, in

spite of the instructions of Amherst to the

contrary. Rogers himself had lost but one man, an

Indian from New England. The church, a fine one for

the time, was burned and a rich collection of

manuscripts relating to Indian life was destroyed.

One ornament, a silver statue, was carried off by

the victors to New England.

There

is no doubt that the massacre was looked upon by the

British as a righteous judgement. These savages,

Rogers says, were ' notoriously attached to the

French and had for nearly a century past harassed

the frontiers of New England, killing people of all

ages and sexes in a most barbarous manner . . . and

to my own knowledge in six years' time, carried into

captivity and killed on the before-mentioned

frontiers, four hundred persons. We found in the

town hanging on poles over their doors, &c., about

six hundred scalps, mostly English.' Rogers set out

for home by a circuitous route. He met with terrible

hardships. Some of his men starved to death, others

found on their route corpses of their own countrymen

scalped and horribly mangled by the enemy, and were

obliged to eat this ghastly food. Ten, it is said,

were taken and carried back to St. Francis, where

they were tortured to death by furious Indian women,

whose lives they had probably spared. For some time

haggard and worn men continued to drift into the

various French and English posts half dead with

exhaustion. Rogers himself returned in the end to

Crown Point and made his triumphant report to

Amherst.

The

savage exploit of Rogers was only side-play. It was

still Amherst's intention to be master of Montreal

before winter. He was now confronted by a

discouraged enemy. The news of the death of Montcalm

had reached Bourlamaque at Isle aux Noix on

September 18. He managed to keep it from the English

and for some days he tried to keep it even from his

own men. But rumours of what had happened began to

be whispered about. When, a little later, to the

news of the death of Montcalm was added that of the

fall of Quebec, there was general consternation.

Bourlamaque tried to restore confidence by saying

that the British, few in number and with winter

coming on, were themselves in an untenable position

and could take no further aggressive action. He says

that the return of Vaudreuil to Montreal was a new

discouragement to the French army; we are left to

conjecture whether it was the impending presence of

the volatile governor or the fact that he was

obliged to fall back from Quebec which caused this

feeling.

Bourlamaque's health was bad; he was worn out by the

fatigues of the campaign of the summer and had been

ill for months with fever, asthma, and other

ailments. Now he hardly undressed to go to bed, and

an old wound kept him from sound sleep. During each

night he made four or five rounds of inspection. The

tone of his letters is naturally despondent. But he

writes : 'We shall fight to our utmost, come what

can.' The Canadians were now discontented and

unwilling to serve. When enrolled, they deserted by

hundreds; a force of five hundred men which Levis

sent to Bourlamaque numbered on its arrival only one

hundred and twenty. The Indians were no better. They

had little taste for the operations of regular war

and went off to their homes regardless of the fate

impending over New France. Bourlamaque says that

even the offer of a keg of brandy would not tempt

them to do scouting work for him.

The

autumn proved stormy and the gales stirred up heavy

seas on Lake Champlain. The season was at its worst

when, at last, Amherst began his advance in force.

On October 13, he embarked his army in whale-boats

and, defended by a miniature navy consisting of a

brig, a sloop, and a floating battery, well armed,

he advanced down Lake Champlain. The array of about

seventy boats was striking enough to have attracted

attention; yet, owing to what must have been glaring

incompetence, M. de Laubara, the naval officer in

command of the French ships on the lake, was not

aware of the approach of the enemy until his own

retreat by the river to Isle aux Noix was cut off.

In face of the overwhelming superiority of the

English he fled down Mississquoi Bay and, when night

came on, sank two of his vessels, stranded a third,

landed his force, and took to the woods. My party

was without food and, in the end, the men were

reduced to eating their own shoes. The sailors

proved helpless on shore and the refugees would

probably have perished in the wilds had it not been

for some Scottish prisoners whom they had with them.

These men, at home in the forest, led the party

safely to Montreal. The fourth vessel of Laubara's

squadron ultimately reached Isle aux Noix, but the

loss of the ships took from the French any

possibility of action by way of the water.

Had

Amherst now pressed in on Isle aux Noix it would

probably have yielded. His foe was delighted at his

inactivity. 'In spite of my belief,' wrote

Bourlamaque, 'that he risks his head by doing

nothing, I begin to think that he will make no

movement during this campaign.' In fact Amherst had

delayed too long. Gales made the lake no longer

navigable to his whale-boats loaded down with men.

He was forced to land on the west shore, there to

wait for better weather. Just at this time news

reached him of the fall of Quebec. It might well

have furnished an added inducement to press forward.

But he did not see-it in this way. Certain now that

Canada must yield, in any case, he turned back to

Crown Point, in order to spare his men the perils of

a needless campaign. It was a thoughtfulness for

which they were not grateful, for it robbed them of

the glory of the final conquest of Canada. 'I do not

know how he will be able to save his head,'

Bourlamaque wrote to Levis concerning Amherst;

'assuredly he is making a stupid campaign.' Yet he

had done something. The French ships on the lake had

been destroyed or captured and the English could no

longer be kept from pressing in when they liked on

the feeble defences at Isle aux Noix. Active

campaigning was now suspended by the approach of

winter. The best that each army expected to do was

to hold its own during that season and to be ready

for effective work in the early spring. |