|

The

distresses of the British in Quebec during this

winter were surpassed by those of the French in

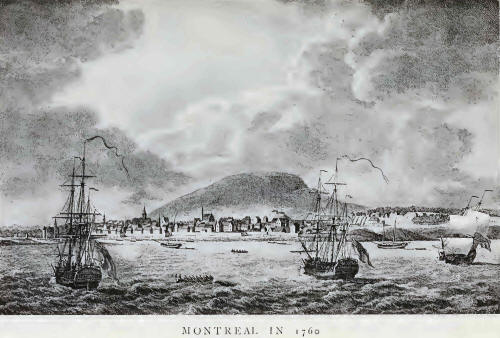

Montreal. In this little town, which was almost the

extreme outpost in New France of European

civilization, the defenders had gathered for the

final rally against the invaders. Usually the town

contained from eight to nine thousand inhabitants;

now, however, its population was greatly increased

by refugees from all parts of Canada. Many of these

refugees had come because they feared not only the

British but also their own Indians, likely at any

time to go over to the enemy and to commit brutal

outrages against their former friends. The savages

were, it was said, particularly incensed against

Vaudreuil, as the cause of the misfortunes in which

they found themselves included, and threatened to

kill him. Leading citizens from Quebec were now in

Montreal, and the Bishop of Quebec ruled his church

from that place. In Montreal was also what remained

in Canada of a Court, which once had imitated

Versailles. An appearance of old-world luxury marked

this town on the edge of the wilderness. 'From the

number of silk robes, laced coats, and powdered

heads of both sexes, and almost of all ages, that

are perambulating the streets from morning till

night,' says Captain Knox, who saw the place in the

autumn of 1760, 'a stranger would be induced to

believe that Montreal is intirely inhabited by

people of independent and plentiful fortunes.' Some

years earlier, the Swedish traveller Kalm had

described the inhabitants of Montreal as 'well-bred

and corteous, kwith an innoccnt and becomming

freedom'; to Knox, who saw them under the shadow of

defeat, they appeared cheerful and sprightly. Their

town stretched in a thin line for two and a half

miles along the river front, 'For delightfulness of

situation,' says Knox, 'I think I never saw any town

to equal it.' Its few streets were regular, though

narrow, and its houses were well constructed. Knox

could find it in his heart to describe the public

buildings as beautiful and commodious, and one of

them at least as 'extremely magnificent'. He thought

Montreal 'infinitely preferable to Quebec'. Quebec,

however, was now associated in his mind with

pestilence and famine. The Chevalier Johnstone, who

served on the defeated side, thought Montreal a

dismal place.

The

picture that we get of the social life of the colony

at this time is not edifying. In New England

Puritanism was still a living force, manners were

grave, life was simple, and the tone of society was

pure and restrained. In New France, on the other

hand, reckless extravagance, corruption in business

methods and immoral licence in social life had long

been characteristics of the upper class of society.

The men who held office in Canada were nominees of

the French Court, and some of them reflected in the

distant colony the abandoned tone of the worst

circles at Versailles. In Canada, as in France,

there were not wanting voices of protest. The Roman

Catholic Church in Canada had always stood for an

austere view of life, and, with hardly an exception,

her priests had supported it by their example and by

their discipline over their flocks. At Montreal the

priests of the Sulpitian Seminary were a powerful

corporation, lords of the whole island under feudal

tenure, and they showed a desire to keep up a

censorship of morals. A hostile critic says that

they asserted a right to supervise what was done in

private houses, and that even the French generals

trembled under their authority for fear of reports

which might be sent to France. The Bishop of Quebec,

Monsignor Pontbriand, now living at Montreal, was a

high-minded and holy man. In this crisis he exhorted

Canadian society to consider its misfortunes as a

call to prayer and to repentance for its sins. There

is, however, no evidence that the call to greater

seriousness was heeded. In time of disaster men are

as likely to fall into reckless licence as to reform

themselves. Montreal during this winter of 1759-60

had the same surface gaiety, the display, and,

beneath all, the ugly self-seeking and corruption

which were gnawing at the heart of the older society

and leading to revolution.

The

real business man in the administration of Canada

was the Intendant, Francois Bigot. Under the system

which had developed in France, each French province

had two high officials, the Governor and the

Intendant, the Governor representing the dignity and

the military power of the Crown, the Intendant

discharging the sober details of civil business. A

similar system prevailed in Canada. The dozen or so

Intendants who had held the office had been on the

whole competent and honest men ; Bigot, the last of

them, was surpassed by none in competence but he was

wholly wanting in conscience, and his career in

Canada was marked by unscrupulous pillage of the

King, his master, and by lavish expenditure, on a

scale that seems hardly credible when we consider

the poverty of the colony.

Bigot

had attractive qualities. He was able and assiduous

in the discharge of his official duties, and during

this winter, when, in some degree, he was forced to

make bricks without straw, he performed wonders in

securing provisions for the army. 'No one shows more

foresight and ingenuity than you to find resources'

Levis once wrote to him. But while a keen man of

business he had also the tastes and ambitions of a

man of fashion, and he made both Quebec and Montreal

scenes of social dissipation, more suited to the

life of a European capital than to that of a town in

a poverty-stricken colony. He belonged to a family

of Guienne, not, it is true, ranking among the

nobility of France, but conspicuous in what had

almost become another nobility, the men of the robe,

the class from which the judges, the lawyers, and

officials like the Intendants were drawn. He had at

court powerful relations who held high official

position—the Marquis de Puysieux, the Marechal

d'Estrees, and apparently, too, the Comte de

Maurepas, a former Minister of Marine. He loved pomp

and it had been his ambition to retire to France to

live in luxury and ease for the remainder of his

life. Already he had bought land; he had grand ideas

of the style in which he should live, and had

purchased furnishings for his house and table on a

lavish scale. When misfortune overtook him and his

effects in France were seized by the King, great

nobles like the Marechal de Richelieu were eager to

become possessors of the plate and other articles in

which he had invested some of his ill-gotten gains.

In

physique nature had not fitted Bigot for the role of

social leader which he aspired to fill. He was small

and fat, with reddish hair and a pimply skin. On the

other hand he had charming manners and he showed a

marked capacity for making himself agreeable. This

social tact was one of his chief gifts. He took

little part in the personal quarrels that had raged

in the colony between Vaudreuil and Montcalm; with

some success, indeed, he had played the part of a

mediator who invariably showed shrewd common sense

in trying to smooth over differences and in advising

friendly co-operation. The villain in the tragedy of

the declining years of New France Bigot undoubtedly

is; but villains would hardly be dangerous did they

not possess some semblance of virtue. Bigot was

loyal and devoted to those who shared in his

pursuits. 'He had great wit and penetration,' writes

a contemporary; 'he was generous and benevolent and

capable of filling a more eminent position than he

occupied; when he had once given his confidence and

his protection it was not easily that he drew back.

. . . His manner of life was unaffected and full of

consideration for those who attended upon or paid

court to him. His table was richly furnished and he

relieved the unfortunate with a generosity that

approached munificence. His love of pleasure did not

keep him from attention to his duty. He was

extremely jealous of his authority and supported too

keenly those who had his confidence and who

unhappily were neither honest nor deserving. To them

only would he listen; their counsels alone would he

follow, and they made him commit stupendous faults.'

Some

of the associates of Bigot were, one should suppose,

conspicuously unfit to shine in that social world

which it was his ambition to adorn. Hardly an

ornament for high social circles was Cadet, the son

of a butcher, and himself, in early years, first a

cowherd at Charlesbourg and then a butcher at

Quebec. His early advance was due to his striking,

if unscrupulous, business capacity. In the early

stages of the war there had been difficulties in the

commissariat department and the French Court had

then decided that, to provide adequate control, a

single official should be given the contract and be

made responsible for furnishing supplies to the

army. Cadet's abilities qualified him to fill this

office, and on January 1, 1757, he entered upon its

duties with the title of Munitioner-General. From

that time he had full control. Canadian society was

astonished that the butcher-knife should have given

place so quickly to the sword which it appears his

new office entitled him to wear. No one, however,

could sneer at his capacity.

In

spite of his coarse manners he was generous and

kindly and so prodigal in expenditure that he made

many friends. In the end the complaisant Vaudreuil

recommended him for a patent of nobility, and

members of his family married into some of the most

ancient families in France.

Corruption was an old story in Canada. The French

Court paid meagre salaries to civil and military

officers and it was a common practice, hardly

censured in high quarters, for these men to engage

in trading operations in order to eke out a

livelihood. Since the system of government in Canada

was completely despotic, officials could easily be

placed in a privileged position in regard to some

branches of commerce. Licences to trade in the

interior, for instance, were issued by the

Government at its discretion. The Government also

exercised the right to name the price of wheat and

other staple commodities. Under a man like Bigot a

system with possibilities of fraud was sure to

receive its fullest development. His secretary,

Deschenaux, was the son of a shoemaker at Quebec. In

some way he made himself indispensable to the

Intendant. Bigot gave him his confidence and clung

with great tenacity to this vain, ambitious, and

arrogant parvenu. So greedy was he for gain that he

declared he would rob even the altar itself. As

secretary to the Intendant, and to such an Intendant,

Deschenaux could easily secure official sanction for

his many plans to defraud the Government and the

people. He and Cadet worked together, and their

rascalities were almost incredible.

A

third person was joined with Cadet and Deschenaux in

the leadership of a ring which planned boldly to

master for its profit the whole resources of the

colony. This third person was Major Pean, a Canadian

by birth, the son of a military officer and himself

an officer. In his case no personal quality secured

the favour of the Intendant. His merit consisted in

the charms of his wife. Bigot had shown openly his

admiration for some of the handsome ladies whom he

entertained so prodigally, but he found his

admiration discouraged either by them or by their

husbands. Madame Pean was not beautiful but she was

young, lively, and witty. When she received the

Intendant's advances, he vowed to make her the envy

of the other women in Canada. In the end the

pleasure-loving Intendant became her slave. ' He

went regularly to spend his evenings with her,' we

are told,2' and she formed

a little court of persons of her own stamp who

gained her protection by their deference and, since

the Intendant could refuse her nothing, made

fortunes. This went so far that those who had need

of promotion or employment could get what they

desired only through her. Domestics, lackeys, and

other persons of no account became storekeepers at

the posts. Ignorance and depravity proved no

obstacle. Employments were, in brief, given to those

she named, without discrimination, and her

recommendation was worth as much as the greatest

merit.' It would not be easy to find, though the

scale is smaller, a more exact parallel of Madame de

Pompadour at the Court of Louis XV than this of

Madame Pean at the Court of Bigot on the confines of

the Canadian wilderness. There is the difference,

however, that the great lady in the Old World had

little part in vulgar corruption and showed

sometimes a sense of responsibility in the use of

power which her copy in the New World lacked. Pean

profited by his own complaisance. Cadet and

Deschenaux found it wise to make him the third

member of the triumvirate, which existed for the

sake of plunder. Among other things Pean was given a

commission to buy grain for the King's service.

Bigot lent him the money for this enterprise. Pean

bought the grain at a low price for ready money. A

little later, Bigot, using his authority, issued a

regulation which named a high price for Brain, and

when Pean sold his supplies he made a great profit.

In

the early days it was Bigot who led in the frauds.

At that time he and one Breard, the Controller of

Marine at Quebec, had worked together in systematic

plunder. They imported goods from France and then

sold them to the Government at a very extravagant

price. Bigot thus used his official position to rob

the King whom he served. At first Cadet was Bigot's

pupil, but he proved to be a pupil so apt that he

soon became the master. It may be that Bigot drew

back from this distorted image of himself. At any

rate the two men quarrelled. Bigot poured contempt

on Cadet as base-born and at last denounced him as a

criminal. Certainly Cadet plundered on a colossal

scale and Bigot's achievements in fraud pale before

his. When both men were found guilty, Cadet was

ordered to pay back from his spoils four times as

much as was required of Bigot.

If

Vaudreuil was not in collusion with the thieves he

was certainly very blind. There was, at times, a

reckless candour in Bigot. Himself corrupt, he

invited corruption in others. Vergor, an army

captain, bad in manners as well as in character,

dull and uneducated, became the friend of Bigot,

probably by sharing some of his vices. Bigot had

secured for him the command at Fort Beausejour, and

this is the style in which the man next to the

Governor in authority wrote, on leaving for France

in 1754, to an officer in a position of trust:

'Profit, my dear Vergor,' wrote Bigot, 'by your

place; trim, lop off; all power is in your hands; do

it so that you may be able soon to come and join me

in France and buy an estate near mine.' Villany is

not often as refreshingly frank and reckless as

this; we almost admire Bigot for his occasional

candour. To Vaudreuil, however, he professed to be a

model of virtue. It seems certain that Vaudreuil

himself was more a fool than a knave. His secretary,

St. Sauveur, was, however, a rascal. When secretary

to an earlier Governor, St. Sauveur had begun to

amass a fortune by securing a monopoly of the brandy

trade with the Indians. Murray spoke of him as a

swindler and traitor, who abused his master's

confidence, and wondered that Vaudreuil could be so

blind. Vaudreuil was, indeed, precisely the kind of

man whom a schemer like St. Sauveur could manage.

Whatever the limits to Vaudreuil's blame, he was, no

more than Bigot, a check to corruption in Canada. He

must at least have seen his own relations profiting

by fraud. It is specifically charged that he made a

large fortune, but his acquittal, when tried in

France after the fall of Canada, leaves the door

open to the belief that he was innocent of anything

but incompetence.

It is

not now possible to fix the share in the frauds of

each of the persons concerned. Towards the end, as

we have seen, Bigot was less active in plunder than

Cadet, but he must have known what Cadet was doing.

There were other great thieves and lesser thieves.

Some members of the ring formed a society that

carried on extensive trade. They had a great

warehouse at Quebec; there was a similar warehouse

at Montreal; and in both places the people came, in

the end, to understand what these warehouses stood

for and named each of them 'La Friponne', the

swindle. One of the Intendant's special friends was

Varin, a vicious libertine, tiny in stature,

insignificant in appearance, but perversely

ingenious to secure dishonest gain. He was an

official in the Government service at Moptreal and

the chief leader in fraud at that place. The ring

had friends and accomplices in France. Some of these

could meet and perhaps silence complaints made to

the Court, others could assist in trading operations

and in sending out supplies. They did some swindling

on their own account. Bigot himself complains of the

inferior quality of goods which they sent out from

France.

One

chief source of Cadet's profits sprang from the

supply of rations for the troops. As the war went on

the number of regular soldiers in the service tended

to decline. No considerable reinforcements arrived

from France, and owing to death, illness, and, above

all, desertion, the troops decreased in number by

nearly one-half. Yet Cadet continued to take payment

for rations for the original number. When there were

only eight thousand men in actual service he was

paid for rations for thirteen thousand. Moreover,

rations charged as containing two pounds of food

contained only a pound and a half. As long ago as

the time when the Romans conquered and plundered

Britain a favourite device of extortion had been to

secure control of the food supply of the people,

then to enhance the price, and finally to sell the

needed grain at a great profit. The triumvirs bought

up as much grain as they could and placed it in

great storehouses on Pean's seigniory of St. Michel

on the river a few leagues below Quebec. To make

sure of scarcity they shipped some of their stores

to other countries. When grain was already becoming

scarce, Cadet secured from Bigot an order to make a

levy on the farmers of grain for the King's posts.

Bigot fixed the amount to be levied, but the ring

went beyond this and took all the grain they could

find. An army of Cadet's employes would descend upon

the parishes in turn. They made each habitant

surrender what they chose to take of his grain or

cattle with no regard whatever to his own needs. For

the grain he would receive the low price named by

the Intendant. For the cattle he received nothing at

the time. The clerks merely made a note of what they

took and the Munitioner fixed the price later,

usually at not more than one-third of what it would

cost to replace the animals. Sometimes the clerks

failed to make a note of all they had taken and the

habitant found redress practically impossible. If he

went to Quebec to make a direct appeal to the

Intendant—upon whose kind heart his distress would

probably have had some effect— he would find it

impossible to see Bigot or to reach him in any way

with the story of his wrongs. A too persistent

complainant might find himself helpless in prison.

When, by such methods, all the available supplies

had been secured and the cry of scarcity had begun,

the Intendant would come forward as the champion of

the needy. He would issue an ordinance, apparently

"preventing extortion by naming a price for wheat,

but fixing a price much higher than that paid by

those who now held the grain. At this price the

Government would buy what it required; the wretched

inhabitants would be obliged to do the same ; and

the conspirators would make a great profit.

Another type of fraud worked equally well. Under

official pressure the import trade of the colony was

easily concentrated in the hands of members of the

ring. By Bigot's influence they imported their goods

free of duty, on the ground that they were for the

King's service. It was Bigot's custom each year to

send to France requisitions for the supplies of the

army and of the civil government in Canada. The

Intendant took good care to order less than was

needed, and when the inevitable deficiency in

supplies appeared the Government was obliged to buy

heavily from the swindlers, and it bought, of

course, at a great advance in price. But this was

not all. The King not merely paid high prices; he

paid for what he did not get. Corrupt officials

certified accounts for goods which were never

delivered, and these accounts were paid in the

regular way. The King paid, too, for goods which

were delivered but which could not possibly be

required for his service. Expensive silks and

velvets, mirrors mounted upon morocco, and similar

articles were included in the commodities said to be

necessary at the posts in the far interior. They

were sold to the King by the corrupt ring, and if

furnished at all were no doubt used by the

plunderers or their mistresses at no cost to

themselves.

The

fur trade was the back bone of the commercial life

of Canada and its profits were very large. Step by

step, the French traders had penetrated farther and

farther into the interior until, about twenty-five

years before the fall of Canada, the Canadian

brothers La Verendrye had actually reached the

foot-hills of the Rocky Mountains. The fur-traders

needed military protection, and to provide this

France had built forts and trading posts on the

chief rivers and on the Great Lakes as centres of

trade with the Indians. The forts were in command of

military officers and were of course a part of the

military equipment of Canada, supported by the

Government. To them supplies were carried at the

King's expense; to them also presents were sent for

the Indians, in order to keep them friendly.

Obviously such a situation furnished the opportunity

to plunder. The route to the interior was at best

difficult and exposed to accident. The transport was

by canoes, and those who set out from Montreal even

early in the spring would be unlikely to make the

long journey and to return to Montreal before the

autumn. The rivers and lakes were often stormy.

Heavy sacks had to be carried across portages on

men's backs. On such journeys, even with an honest

accounting, the King's stores were likely to suffer.

But there was not an honest accounting. What was

easier than that kegs of brandy should become more

than half water on the long journey? What was more

simple than to sell a keg of the King's brandy or a

package of the King's goods to some trader met by

the way and then to report that it had been thrown

overboard to save the canoe while crossing a stormy

lake? In the hands of Cadet and his friends it was

sure to be the King's goods that suffered by such

mishaps.

The

pillage in connexion with the forts and posts in the

interior was so rich that positions of influence at

these places came to be much coveted. An

unscrupulous man could make requisitions and certify

bills for many times the amount of the goods he

received, and he and the officials at Montreal and

Quebec would share in the profits of the robbery.

The so-called presents for the Indians were in

reality sometimes sold to them. Goods sent as

supplies for the King's troops were also sold. Furs

bought with the King's money and worth great sums

were appropriated by dishonest officials and sold

for their own benefit. It is clear that some of the

military officers at the forts took part in this

plunder. But the officers who fell were, for the

most part, in the colonial service and long resident

in the colony; few officers of the regular army who

served in the regiments of Montcalm and Levis were

involved. Courage and honour were not passports for

securing or holding a position at a fort or trading

post. Those who would not lend themselves to the

plans of the leaders were likely to be turned out of

their places. It happened that men too persistently

honest were imprisoned on some trumped-up charge. A

year or two in the interior gave time for amassing a

considerable fortune.

Another opportunity for fraud was found in the

contracts for transporting supplies to the forts in

the far interior or from Quebec and Montreal to

adjacent points. We have details of what happened in

connexion with transport from Montreal to St. Johns

and Chambly, forts not many miles away, on the

Richelieu River. In the name of persons who, in

reality, had only a slight interest in the contract,

Pean and others undertook this work. The King

furnished the boats ; they were taken to the mouth

of the Richelieu River at Sorel by the King's

soldiers, and from there up the river to their

destination by habitants impressed in the King's

name, under what was known as a corvee. For such

service the contractors paid out almost nothing, but

they charged the King a high price. In addition to

this their accounts against the King were sometimes

paid more than once.

The

plunderers made profit even out of the misfortunes

of the Acadians, people of their own blood. These

had been driven from their homes in what is now Nova

Scotia, partly by the policy of the French, who did

not wish them to remain and accept British rule, but

more completely by the British, who expelled them

from their farms because they would not take the

oath of allegiance. Those who, helpless and poor,

found refuge within the frontier of Canada, were in

an especial degree the wards of the King of France.

The Court was ready to help them and at great cost

sent food and supplies for this purpose. Here was an

unexpected opening for fraud. These supplies were

forwarded to the Acadians from Quebec, and from

Louisbourg, before it fell. The King paid for good

food for them ; but they were fed with bad food or

not fed at all. Some goods disappeared entirely on

the way. With what seems to us grim humour these

starving Acadians were supposed to need for their

comfort damasks, satins, and other articles of

luxury. These were accordingly bought for the King

at heavy cost, and were then sent at great cost to

points far remote, there to be sold at a low price

to the Acadians in order to help them. Not the

Acadians, however, but representatives of the

corrupt ring bought them, for almost nothing, and

sent them back to Quebec to be sold at their real

value. It was, we are told, 'a pretty woman' (une

jolie femme), to whom Bigot could refuse nothing,

who managed this fraud. Many of the unhappy Acadians

were brought to Quebec in the year after their

expulsion. It was a time of scarcity. They were

denied bread and were fed on horse-flesh. Many of

them died. These homeless people were not allowed to

go to the places in Canada which offered the best

chance of success. Those who were willing to settle

near Quebec on Madame Pean's seigniory and also on

Vaudreuil's seigniory were given the adequate help

denied to others. Misfortune was no protection

against the cruelty of the plunderers.

When

the Acadians presented paper money at Quebec,

Bigot's secretary, by delay in redeeming it, forced

them in the end to accept one-half or one-third of

its face value. Later he himself received from the

Government the full amount.

It

must not be supposed that no voices of protest were

raised against this system. Montcalm had seen what

was going on. Some of the officers in the French

service were, he said, 'stealing like mandarins',

and the pettiest ensign was growing rich. The mode

of living in Canada in Bigot's circle attracted

attention, for it became extravagant beyond measure.

In a country chiefly remarkable for the poverty and

want of its people, men were building large houses,

driving expensive equipages, and gambling for

excessive sums. Cases of the rapid accumulation of a

fortune were much talked of. A certain Pillet at

Lachine made 600,000 livres in a single year by

transporting the King's goods. Another inhabitant of

Lachine made a fortune out of charges for storing

the King's goods in his house; needless to say, the

King's goods placed in his custody were plundered.

The Church, to her credit, spoke out against the

scandals. The author of the most scathing account of

these evils 3tells us that

he was himself present in a parish church when a

priest described and attacked the frauds. He called

those who received the stolen goods thieves, blamed

the Intendant and the Governor for what was going

on, and demanded restitution to those who had

suffered. A whole battalion of troops was present to

hear this sermon, as were also many of the

inhabitants. The fact that those who shared in the

frauds were either natives of the colony or had been

resident in it for some time is best explained when

we remember that its life had long been corrupted by

this system and that permanent residents in the

country were in better position than were new-comers

to share in the plunder.

Very

little gold or silver was in circulation in Canada

and business was carried on with the medium of paper

money. A part of this was in the form of cards

issued by the authority of the French Court. But,

since the total amount of the card money was only

one million francs, this was not enough to carry on

the business of the country, and the Intendant had

supplemented it by a system of his own. As occasion

arose he issued what were called ordinances. These

were the equivalent of the modern banknotes and

ranged in amount from one franc to a hundred francs.

They were accepted everywhere for purchases by the

Government and they formed the chief currency of the

colony. If a holder wished to have his ordinances

redeemed, all he had to do was to present them in

October at the government offices. In return he

received drafts on the royal Treasury in France

which were duly honoured. As long as the credit of

France was good and it was certain that the drafts

would be met, all went well. Until the autumn of

1759 the ordinances seem to have been accepted

everywhere without much question.

But

now the system was breaking down. In October 1759

France herself suspended payment for a time on no

less than eleven descriptions of stock, and Horace

Walpole says that on the list of bankrupts drawn up

in all seriousness in England was the French King,

under the name of 'Louis le Petit, of the city of

Paris, peace broker, dealer, and chapman.' The

drafts from Canada, due in this year, were not paid,

and the Government announced that none would be paid

until the peace. This of itself would have

discredited the ordinances. But there were other

causes of unrest. For some years the French Court

had protested against the excessive amount of the

drafts of Bigot. Repeated charges of corruption had

already been made against him, and an official, M.

Querdisien-Tremais, was now in Canada to inquire

into Canadian finance. Matters had gone beyond the

Intendant's control. M. Querdisien-Tremais wrote to

the Minister on September 22, 1759, only a few days

after the fall of Quebec. He says that he has found

it difficult to get information. The greatest

disorder exists. Every kind of officer from the

highest to the lowest engages in trade, and the

greed for gain is insatiable. Discipline in the army

is relaxed and the common soldiers are given the

greatest licence.

Bigot

was in the power of those who had aided him in

rearing the stupendous fabric of fraud, and they now

showed increased eagerness to lay hands on all they

could get before the final collapse. From the fall

of Quebec to that of Montreal the only thought was

of brigandage. There was a torrent of corruption.

When Bigot could no longer gratify his partners in

dishonesty they began to abuse him. His generosity

had made for him not friends but ingrates. To keep

them quiet, the Intendant was obliged to let them do

what they liked, and he found their demands

insatiable. In this autumn of 1759 new plunderers

were sent to the interior posts to make what they

could while yet there was time. Soon staggering

demands came in from the posts— accounts with the

proper amount multiplied by five or six. Levis, new

to the supreme command, received invoices amounting

to great sums for supplies for the King's service.

He was in no position to verify them and he let them

pass. He moved freely, too freely some of his

friends thought, in the society that profited by

fraud. His relations indeed with the wife of one of

the chief swindlers were such as to cause scandal.

The demands upon the Treasury became ever more

excessive, the volume of outstanding ordinances was

greatly increased, and it was more than doubtful

whether the Court could or would honour the drafts

now to be made upon it to redeem the ordinances.

Bigot, who, after the fall of Quebec, made his

headquarters at Montreal, was in a desperate

position. It was October, the month when he must

redeem the ordinances and issue the drafts on France

for sums that would startle the Court. With the

British fleet in command of the river it was very

doubtful whether any communication with France was

possible. Early in October, using what was, in the

circumstances, not an invalid excuse for haste, the

Intendant sent a crier through the streets of

Montreal to announce that only three days would be

allowed for presenting the ordinances at the

Government offices and securing drafts on France. Of

course those who did not present them within that

time must keep them for at least another year, and,

with Quebec in the hands of the English, another

year would probably see the entire ruin of the

colony. The Intendant's plan caused commotion. Many

of the ordinances were held outside of Montreal and

it was impossible to present them during the limited

time that had been named. After some days Bigot's

house was assailed by those who had brought their

paper money, only to find that the days allowed by

him had expired. Vehement were the curses upon the

Intendant. His course meant ruin for nearly every

one and especially for those who held these

ordinances as their only pay for supplies sold to

the Government. It was double robbery to have their

goods taken at a low price and to be paid in money

now rendered worthless. But Bigot persisted; a

precipice was before him, a wolf behind ; if he

failed to take up the ordinances in Canada the

Canadians would be against him; but if he took them

up by heavy drafts on France the Court would be more

alarmed than ever and might repudiate him entirely.

His action in demanding the sudden presentation of

the ordinances made worthless those that remained,

and speculators will soon able to buy them at about

one-fifth of their face value. A cynic might say,

indeed, that this collapse hardly mattered, for the

complete ruin of the colony was imminent in any

case. The Government's credit was gone. Since no one

would take the paper money, Levis, when he needed

resources, was obliged to borrow what gold and

silver his officers and men possessed. This left

them in a pitiable plight. Some of the officers sold

even their clothes to supply their wants.

In

such a situation it is obvious that at Montreal in

the winter of 1759-60 the Gallic gaiety was

subjected to some strain. Vaudreuil was already

there when Levis arrived in person to make it the

centre of his plans against Quebec. Reports reached

the British that Montreal was facing its tasks

cheerfully. Dim echoes of the gossip of the time

reach us. Vaudreuil's personal conduct appears to

have been immaculate ; in regard to him and his

devout wife scandal is silent. Levis, on the other

hand, was no better, and probably no worse, than the

average courtier of his age. His favourite saying

that ' one must be on good terms with every one ',

shows that he could adjust himself to his

surroundings. With his conspicuous graces of person

he made himself agreeable to the ladies of Montreal.

In spite of the shadows hanging over this society,

it managed to amuse itself. The Intendant, the

officers, and the ladies all alike gambled with a

passion and on a scale startling even to those

familiar with gambling scenes in France. They danced

: Montreal was as gay as Versailles. We hear

sometimes of bitterly cold weather, but, since no

opposing army was near to cut off access to the

forests, Montreal was not in the same distressing

straits for firewood as Quebec. Prices were,

however, high. A cord of wood, which usually cost as

little as six livres, was now sold for from eighty

to a hundred livres. Provisions were so scarce that

even persons who had money found it difficult to buy

what tv needed. WhenBent drew near there was

unconscious humour in the Bishop's permission to

omit the usual Lenten abstinence. He commanded

instead prayers for a happy issue from adversity and

for a speedy and enduring peace between the two

crowns.

Perhaps to inspire his followers Levis professed no

misgivings about the future; he talked as if he had

only to present himself before Quebec to ensure its

falling into his hands. In words the French could

hardly have been more certain had Quebec already

fallen. Any one expressing misgivings was denounced

as ' English '. An amusing comment upon this

gasconade was furnished when Montreal fell into a

panic in March at reported traces in the adjacent

forest of an English camp. The alarm was needless.

What had been discovered was an old camp abandoned

by the French. Sometimes Levis spoke of a wild

scheme, which Montcalm had also cherished, of

leaving Canada to its fate and of leading his forces

farther into the interior, past Lake Ontario and

Lake Erie and down the Ohio and the Mississippi to

Louisiana. This was, however, in his darker moments.

What he really hoped for was to keep up the fight

until, at an early date, as he expected, peace

should be concluded. Meanwhile he faced his tasks

cheerfully enough.

There

were disagreements with the British over the effects

which the French officers had left in Quebec. The

British had agreed that these should be returned to

their owners. Vaudreuil sent some schooners down to

Quebec bearing his own maitre d'hotel, Bigot's

valet, and other servants to recover and bring back

the numerous trunks and packages. On the plea that

these servants might be officers in disguise, who

would take military notes, the British refused to

allow them to go about freely in the town. The

garrison sent to France had been allowed only one

day to claim their belongings, and the British at

first insisted that only this time could now be

allowed for the later claimants. The effects must,

they said, be collected in the morning and examined

and sealed and shipped the same afternoon. M.

Bernier, the commissioner, was in despair. There

were not fifteen carters in the whole town. ' One

might as well try to seize the moon with one's

teeth,' he said, as to do what was required. He had

lost his horse and had worn himself out going on

foot from the General Hospital to the town. In the

end the British relaxed the conditions somewhat. A

crier went through the town to order those who had

effects to embark to get them ready. A good many

people had requested M. Bernier to claim their

property for them. In some cases these belongings

had been moved to other places. It happened, too,

that owners had given inadequate directions. ' I

should have needed a thousand legs if I had done all

that was asked of me,' Bernier says. Two British

officers accompanied him from eight o'clock in the

morning until five in the evening. ' I did nothing

but run from the Upper to the Lower Town with the

two examiners, going from house to house.' He put

his seal on not less than three hundred trunks and

felt, he declares, like an excise officer. He admits

that some of the trunks thus sealed contained

merchandise on which their owners expected to make a

profit of 300 or 400 per cent, when it was sold at

Montreal and other points.

Vaudreuil was fussily busy during these last days of

his rule. He must have kept occupied a small army of

secretaries, for he wrote interminable letters and

memoirs full of petty comments upon events from day

to day, of boastful promises as to what he should

still do to save the colony, and of efforts to prove

to his correspondents his own competence. He was

ignoble enough to attack in a scurrilous way the

memory of the dead Montcalm. So jealous was he of

his rival that he did not shrink from planning to

examine his private papers—a proposal which Levis,

in whose custody they had been left, checked by a

stern letter. Even after this Vaudreuil did not hold

his hand. On October 30, 1759, he wrote a long

letter to the Minister piling up grave charges.

'From

the moment of M. de Montcalm's coming to the colony

until his death he did not cease to sacrifice

everything to his boundless ambition. ... He

tolerated among the soldiers every kind of

outrageous talk against the Government and allied

himself with the most disreputable persons. . . .

Upon the people he or his regular troops laid a

terrible yoke. He abused those who were honest,

supported insubordination, and shut his eyes to the

pillage which the soldiers carried on; he even

allowed them to sell before his face the provisions

and cattle which they had stolen from the habitants.

I am in despair, Monseigneur, to be obliged to paint

such a portrait of the dead Marquis de Montcalm, but

it contains only the exact truth. I should have said

nothing had I remembered only his personal hate to

myself, but I am too deeply grieved by the fall of

Quebec to conceal from you the cause which is

generally recognized by the public.'

At

Montreal Levis had taken up his residence in the

house formerly occupied by Montcalm. The officers

who surrounded him were not a happy family.

Adversity had not brought them to sink minor

differences. Vaudreuil reports to the Minister on

November 9 a case in which officers came to blows.

There were keen jealousies. Vaudreuil's brother, M.

Rigaud, who held the post of Governor of Montreal,

was bitterly incensed because Levis had been placed

over him in authority. He declared that it had been

done by Vaudreuil because Levis, unlike himself,

would shut his eyes to Cadet's frauds. This was a

pretty family quarrel and, in the end, Rigaud

refused any longer to remain under the same roof

with Vaudreuil and sought quarters elsewhere. We

hear echoes of spiteful talk about the liaisons of

Levis ; he boasted that his family was related to

the Virgin Mary, and he relied more upon that, it

was said, than upon attention to his religious

duties. It was an old story that Bougainville's

rapid advancement was attributed to the favour of

Madame de Pompadour; and Vaudreuil's pompous ways

and interminable flow of words come in for some

guarded satire. Many of the officers were, like

Vaudreuil, inveterate letter-writers, and their

correspondence shows how keen were their discords.

Few of them had any interest in or cared about

Canada. To them the ' wretched colony ' as they

often called it, meant nothing. On the whole,

however, these officers were brave men willing to do

a soldier's duty wherever they were placed. Their

letters are dignified and we have from them no real

complaints. But promotion in France is what they

were always aiming at. To secure it they prepared

interminable petitions. One of the chief anxieties

of Levis himself was to secure not merely

decorations as distinguished as those of Montcalm

but something beyond this—the cordon bleu—and his

keenest hopes at this time are, he says, not for a

money reward but for this honour. Talk as he might,

he had little real hope that the colony could be

saved by anything but peace. He could only strive

that he and the other officers should win glory even

from disaster.

Upon

the Intendant fell the responsibility of

provisioning the army in Canada, and he gave orders

to Cadet for supplies which that clever person, now

at war with Bigot, declared he could not possibly

fill. It was at best 'a difficult task to feed the

army and it would have been more difficult had all

the troops been kept at Montreal. They were

accordingly distributed to different points and a

good many of them were quartered on the inhabitants.

These were to be paid fifteen livres a month for

each soldier whom they received. Cadet, while paying

this price, drew from the Government much larger

sums than he paid and was thus able to reap a

corrupt profit for his comfort in a time of

adversity. Sometimes with pay, but also sometimes

without it, When appropriate inhabitants were

obliged to furnish whatever they had that the army

desired. Levis, who admits that he took nearly all

their cattle, at the same time urged his men to

treat them with gentleness. M. Querdisien-Tremais

declares, however, that the French soldiers treated

the Canadians with great brutality, devastating in

the most deplorable way the fields in which their

crops were ripening, robbing them of vegetables,

poultry, and cattle, with a waste that was pitiable

in view of the impending famine. The Chevalier

Johnstone says that the Canadians were 'devoured by

rapacious vultures', who fattened while their

victims starved. 'The gentlemen and officers are

very devils at taking the cattle of the

inhabitants,' Bigot wrote. Plundering was not the

less unwelcome to the habitants because it was done

by nominal friends. When their cattle were carried

off in the name of the King, the owners received so

poor a price that the seizure amounted to

confiscation. On the other hand, when the people who

received so little wished to buy, they found prices

excessive; a pound of butter cost from twelve to

fifteen livres (the livre being substantially the

equivalent of the modern franc), a pound of mutton

three livres, a hen twelve livres, a pair of woollen

socks sixty livres, a pair of shoes thirty livres,

and so on.

In

time the Canadians must have learned, in some

districts, at least, to conceal their cattle from

the plunderers, for the British found an adequate

supply in the country in the autumn of 1760. Murray

says, indeed, that horse-flesh was served to the

troops in Canada when cattle were not scarce,

because the supposed famine would justify the

charging to the King of great sums for provisions.

At Quebec, compared with Montreal, provisions seemed

abundant and cheap. Murray was quite willing that

Levis and his officers should be supplied with

wines, coffee, sugar, and other luxuries from

Quebec. Matters went, however, far beyond this.

Johnstone says that French officers at Montreal, '

whom one would have taken for merchants rather than

for military managed, during the winter, to carry on

an extensive trade with the British at Quebec. These

officers brought provisions to Montreal and sold

them there at such prices as to make fortunes.

Murray remarked that their conduct gave him a poor

opinion of their characters. The French officer,

Malartic, even declared that, in spite of famine at

Montreal, provisions were sent down the river from

that place in exchange for large quantities of wine

and brandy. So heavy was this traffic that, while

food remained dear, wine and spirits fell in

Montreal to one-fourth of their former price.

Careful soldiers saw danger to French interests in

the visits of traders to Quebec. They would divulge

the French plans, wrote Colonel Dumas, since the

terror which General Murray inspired would make the

best-intentioned tell everything.

It is

not easy to determine what were the wishes and hopes

of the inhabitants of the country as a whole.

Already there was a deep cleavage between the colony

and the motherland, and probably the majority of the

Canadians would have seen gladly the end of the war,

even at the cost of conquest by the British. As soon

as Quebec fell the unwillingness of the Canadians to

serve longer became very marked. Nor need we wonder

at their attitude. About four thousand of their

houses had already been burned by the British enemy.

Now a more savage enemy threatened them, for, as

long as the war endured, every village had a

haunting dread of the Indians. The French leaders

had never checked with sufficient rigour these

uneasy allies and now in the days of France's

adversity they were likely to commit bloody

excesses. A few outrages did occur. The losses which

they caused were, however, trifling compared with

the exactions and privations which the Canadians had

to bear at the hands of their own defenders. The

Chevalier Johnstone wondered indeed at the brave

endurance of the people who 'suffered their

oppressors without a murmur'. Vaudreuil could still

speak of their goodwill and zeal. Yet many served

sullenly enough. Most of the Canadians had returned

to their homes for the winter, and now when summoned

for any special service they employed every device

to escape the unwelcome duty. The frequent excuse

was that they were ill. If these answers represent

the truth we must conclude that during the winter

whole villages were stricken simultaneously with

some malady. 'All the world is ill,' wrote Bigot of

the Canadians. Famine was indeed a universal cause

of illness. The Chevalier Johnstone describes the

wan and starving appearance of villagers, whose

supplies of food were carried off without payment to

the owners. At the military centres it was

noticeable that the Canadian soldiers were more

subject to illness than the French, owing, no doubt,

to inadequate nourishment and want of proper

clothing to meet the severe weather. The civilian

population suffered fearfully. Those who dwelt in

Montreal were hardly better off than the farmers in

the outlying villages. Commerce was ruined, and the

daily auction sales of personal effects showed

either the pressing need of money or the desire to

get rid of encumbrances and to quit the distressful

land as soon as possible.

In

spite, however, of discouragements we still find in

this demoralized community the supreme desire to

retake Quebec. Every one had a plan, including, as

the Chevalier Johnstone says contemptuously, 'women,

priests, and ignoramuses.' Long memoirs on the

all-important subject were prepared and submitted to

the leaders. Even the Bishop of Quebec joined in

showing how Quebec could be taken. One memoir

suggests that, since exact information of what is

being done in Quebec is needed, the Jesuits should

be asked to furnish spies. 'They are able to inspire

the necessary zeal to risk even life in a task to

which the motive of religion may properly be

related.' All the plans agreed on the main points

that a large force—not less than 8,000 men—would be

required and that the army must take with it a

supply of ladders to aid in scaling the walls of

Quebec. The writers discuss such small details as

that the ladders must be sharp at the bottom in

order to hold in the frozen ground, and that they

must have hooks at the top so as to rest firmly on

the walls ; their exact length is also to be

prescribed. Some hoped that with the aid of spies

Quebec could be surprised ; others, with more

reason, despaired of this and thought that the only

way would be to attack it openly, to tire out the

garrison by repeated alarms until they surrendered,

or until, with the aid possibly of a snow-storm, the

town could be carried by assault. Should this

happen, the garrison must be put to the sword since

there were not provisions to feed them; the French

could then live on the supplies of the British and

await in security the arrival of succour from

France.

The

engineer Pontleroy criticized adversely these plans

for attack. He thought them certain to fail. After

this failure would come famine more acute, the

discouragement, perhaps the revolt, of the

Canadians, and desertion among the regular troops.

The British, on the other hand, with their

confidence revived, would be more aggressive than

ever. Moreover, if peace came, as he expected,

during the winter, the generals would have vain

regrets over the futile sacrifice of brave men. But

even Pontleroy saw that the British must be kept in

fear of imminent attack. Vaudreuil, full of

bombastic courage, was reported to have said that if

Levis would not undertake the attack, he would

himself execute it ' at the head of his brave

Canadians'. Reckless self-confidence led some to

offer a practical demonstration of the way to take

Quebec. In one district, where a supply of ladders

had been secured, practice in escalade was made on a

neighbouring church. People flocked from the

parishes to see the gallant performance. But the

would-be assailants of Quebec were too impetuous.

They rushed headlong to the mock attack; some

ladders slipped, others gave way, and broken heads,

broken arms, and broken legs were numerous. 'These

accidents' writes Captain Knox, '... so effectually

chilled the enterprising natives, who were the first

promoters of this Quixotic undertaking, that they

positively refused, upon the ladders being replaced,

to make further trial, concluding it would be

impracticable to recover the town by insult or

escalade.'

The

French outposts near Quebec had some trying

experiences. At Jacques Cartier the officer whom

Levis had placed in command, Colonel Dumas, a

competent man, but timid about taking

responsibility, spent the winter in deadly fear that

Murray would advance and overwhelm him. The

inhabitants of the neighbourhood circulated wild

rumours which changed from day to day. When he

called upon the people for service he found that

every one was ill. So uncertain was he of his own

men that he lived in daily dread lest the British

should bribe some of them to burn the fort. In March

1760, a fire did break out in the bakery, by

accident it should seem, and it was little short of

a miracle that the flames did not reach and explode

the magazine. When Dumas tried to muster the

inhabitants for an attack on Quebec, only four came

from a village which had been expected to furnish

fifteen. To his comfort, however, the four brought

with them provisions to last ten days. When he

brought in the few cattle that his district

furnished the poor creatures were so lean that it

was hardly worth while to kill them for food. A

remnant of the Indians of St. Francis, who, owing to

absence with the French, had escaped the massacre by

Rogers, deserted the south side of the river and,

crossing to the north, reached Dumas at Jacques

Cartier. When he rebuked them for having abandoned

M. Hertel, who was trying to organize the French

forces in their own district, they went off in a

rage, killing some of the wretched inhabitants as

they went. The incident is characteristic of the

slight control which the French had maintained over

their savage allies throughout the war.

We

have seen Bourlamaque's efforts at Isle aux Noix to

check any English advance from the south. Far up on

the St. Lawrence, near the head of the rapids, the

French still held the mission station known as La

Presentation. No longer did they rely, however, upon

its weak defences. During the autumn and winter they

built a new fort on an island a few miles below the

place which Gage had feared to attack in the autumn

of 1759. This fort was named Fort Levis, in honour

of that general. The officer in command at Fort

Levis found it almost impossible to get work done on

the defences. By the end of October, 140 men of his

small force had deserted, and after this others

continued to go off with impunity. Demoralization

was general. The workmen, ready to do everything but

their proper tasks, spent the time in providing for

their own comfort and amusement rather than in

building the fort. Chimneys built with great labour,

but without proper mortar or other material, came

clattering down when a fire was built, and there was

the imminent prospect that the barracks would be

without heat during the severe winter. Desandrouins,

the engineer in charge, was so inconsolable at this

disaster that, for a time, he would take no food and

seemed likely to fall ill. A great need of the

builders was sawn planks. A Jesuit at a neighbouring

Indian settlement, St. Regis, said that if men and

supplies of food were given him he would furnish the

needed planks. When seven men were sent the Jesuit

used their labour for his own purposes and sent them

back empty-handed. Later he had the temerity to

plead that twenty men were really necessary, but

were not supplied. 'We have always been the dupes of

the Church,' writes a French officer in disgus; 'now

we must be on our guard against her seductions.' In

the end, owing to scarcity of provisions, Levis was

forced in January to withdraw two-thirds of the men

whom he had sent to build the new fort.

In

the end the French centred their hopes in two

designs: they would attack Quebec while the frost

was still in the ground and Murray could not throw

up defences on the Plains of Abraham; and, once in

Quebec, they would await the succour from France

without which every plan must fail. Upon this aid

from France all hopes centred. After the fall of

Quebec Vaudreuil had sent Le Mercier, the chief of

the Colonial Artillery, as an envoy to France. He

succeeded in getting away in one of the French ships

which were able to leave Canada after the departure

of the British fleet. Twenty years earlier this man

had gone to Canada as a private soldier. He was

suspected of sharing Bigot's frauds ; certainly he

had secured both riches and promotion in Canada, and

he was not likely to encourage adverse inquiries

into a system by which he had greatly profited. He

must have carried with him a heavy packet of

dispatches, for those that remain to us are

voluminous. He took, of course, the apologia of

Vaudreuil for what he had done. Both the Governor

and Levis wrote that the prime need was food and

that the sheer force of famine, more dangerous than

the enemy, must compel them to surrender by May if

help were not forthcoming. In any case the King

would lose some of his subjects by starvation during

the winter. The fleet for Canada should set out not

later than In February, so that it might be waiting

at the mouth of the St. Lawrence to ascend the river

at the first moment possible after the breaking up

of the ice. Ten thousand men, provisioned for two

years, and a full equipment for aggressive war would

be necessary to save the colony; but, with such aid,

Levfop said he could retake Quebec. He now based his

plans on the expectation that Le Mercier would

succeed and that, at the proper time, the required

help from France would be forthcoming.

France, however, showed no resolve to aid her

perishing colony. The nation was engaged in a

titanic struggle in Europe not only against the

genius of Frederick the Great, but also against the

wise recklessness of Pitt. There was bitter irony in

the remark of 'Junius', that England owed more to

Pitt than she could ever repay, ' for to him we owe

the greatest part of our national debt, and that I

am sure we can never repay.' In order to humble

France Pitt spent money with appalling profusion; in

1760 alone he demanded votes for £16,000,000. Lord

Anson, the first Lord of the Admiralty, is one of

the ablest organizers in the whole history of the

British Navy. To Pitt's impatience, however, he

often seemed slow and, on one occasion, Pitt had

threatened to impeach him if his action was not more

rapid. With Pitt driving Anson something was certain

to be done. The display of naval force in America

was to be overwhelming. Commodore Lord Colville

remained at Halifax during the winter with five

ships of the line and four frigates. In the early

spring these were to join in the St. Lawrence a

squadron of equal strength under Commodore Swanton

sailing from England, while/ at the same time,

Captain Byron was to take five warships to

Louisbourg. Such vast outlay and energy France could

not rival.

French policy was, moreover, becoming adverse to

adventures over the sea. The disastrous defeats of

1759 in both Europe and America, together with

impending defeat in India, may well have led France

to conclude that she was fighting her foes on too

extended a front. Powerful voices like that of

Voltaire were raised for the abandonment of Canada.

The colony, it was claimed, cost France large sums

and took from her, to plant amid harsh conditions

and in a severe climate, people whom she needed at

home. Canada would be ever at the mercy of the

enemy. England, with a large population in her

colonies in America, could always seize Canada and

exact from France sacrifices in Europe in order that

she might get back her possessions in America. It

was said, moreover, that in the vast spaces of

Canada republics, not monarchies, would ultimately

be formed and these would prove a menace to the

monarchy in France. On the other side, the devout

urged that if France let Canada go the Protestant

heresy would prevail everywhere in North America and

many souls would be lost. Moreover, the English

would take not only Canada; they would become

undisputed masters of the sea ; they would expel

France from the chief nursery of her navy, the cod

fisheries ; they would drive her from the West

Indies. And it was not merely France that they would

check; they would seize the possessions of Spain and

Portugal. In a word, if France lost her footing in

Canada the whole world would be handed over to the

Anglo-Saxon, and America in particular to

Republicanism and to heresy.

Such

arguments, fervid and ingenious as they were, proved

of little weight to secure effective help. At the

ministry of war was the Due de Belle-Isle, Marshal

of France. Born in 1684, he was a veteran who had

frequented the court and had served in the wars of

Louis XIV. Though a man of ability and decision, he

was now seventy-six years of age, weary of the tasks

from which death was soon to call him, and

ineffective compared with an adversary possessing

the fiery energy of Pitt. A year earlier, in

February 1759, Belle-Isle had written to Montcalm to

show that France was on the horns of a dilemma which

made help impossible. If she sent aid the British

would either capture it en route or they would be

incited by France's efforts to greater efforts of

their own. So Montcalm was told to shift for

himself. Levis now fared a little better. On

February 9, 1760, Belle-Isle wrote to say that the

King had been much touched by the death of Montcalm

but that the cause of France was in good hands with

Levis in command. Rescue, in the shape of food,

munitions of war, and men, would be sent so that

Levis should be in a position to dispute Canada foot

by foot with the English.

The

event proved, however, that France could do little

or nothing which involved the power to cross the

sea. From the first her policy in this war had been

fatal to her best interests. Her reasons for taking

so fatuous a course will probably always remain

something of a mystery. At a time when, on the

continent of Europe, she was menaced by no dangers,

but when, across the sea, she was in vital danger of

losing all her possessions, she had chosen so to

embroil herself in a land war in Europe that she

could not build up her navy. Sometimes the weak and

inefficient Louis XV, out of a mere love of secrecy,

would himself carry on important negotiations

without the knowledge of his ministers. Perhaps it

is chiefly to this that we owe the inept policy of

France. Austrian policy was at this time directed by

an able Minister, Kaunitz, and in some way he had

lured France from her real interests. For

generations France and Austria had been enemies.

Suddenly, with nothing to gain by her course, France

had abandoned her old alliances and had joined

Austria in an attack on Prussia ruled by the

greatest soldier of the age, Frederick the Great.

Austria had demanded ever new sacrifices from her

ally, and France, facing eastward to help Austria,

failed to meet the attacks of her one dangerous

enemy, Britain. During this war Britain kept France

in a state of alarm similar to that of an earlier

age when the hardy Norsemen had perpetually

threatened the same coasts. Over and over again the

British landed in France and wrought havoc. At last

the French were goaded to make one supreme effort.

They would land a force in Essex, march on London,

and dictate terms of peace before the British

capital. It was this plan which had kept the

Londoner uneasy during the summer of 1759. But his

peace of mind was to return to him. At Quiberon Bay,

in November, Hawke shattered the power of the French

fleet at the very moment when Saunders was arriving

in England from the triumph of Quebec. It is true

that even after Quiberon, in February 1760, the

French privateer Thurot landed near Belfast in

Ireland and made that city pay an indemnity. This

was, however, merely a flash in the pan. After

Quiberon France could do almost nothing on the sea.

It is

thus clear that the hopes of Levis for rescue by a

fleet in the spring of 1760 were hardly, in any

case, justified. They were rendered less likely of

fulfilment by the character of Berryer, the

Secretary of the Navy in France. French naval policy

had long been indecisive in character. There were

five secretaries between 1749 and 1759, each with a

policy of his own. Under Machault (1754-7) the navy

was directed with vigour and success. La

Galissonniere defeated Byng in the Mediterranean in

1756 and, as a result, the French took Minorca. But

Machault was so incautious as to say unflattering

things about Madame de Pompadour and he was

dismissed in 1757. In 1759 that lady was able to put

one of her friends in charge of the navy. Berryer

had been a Lieutenant of Police and knew nothing

about naval matters. The Chevalier de Mirabeau,

vigorous in expression after the manner of his

famous family, once declared in a rage that Berryer

was the enemy of all that was honest and as black in

soul as he was in skin. The words call up a physical

as well as a moral image and are probably not too

just. Certainly, however, Berryer was coarse,

brutal, and incapable. Belle-Isle, competent even in

his extreme old age to plan for the army, hoped to

find Berryer an effective colleague in the navy. He

supported his appointment but soon learned his

mistake. Berryer would take no advice and was too

strong in favour at Court to be dismissed. His one

idea of naval policy was to reduce expenditure.

Since Britain, with her life dependent on sea power,

would use her whole resources to maintain her fleet,

France, said Berryer, could not rival her and need

not try to keep up a navy. He sold to private

shipping interests some of the naval stores in the

arsenals. His taste for detail was such that we find

him inquiring why twelve sous are charged a day for

feeding cats to kill rats in the arsenal at Toulon.

Since money would be saved he saw no reason, he

said, why officials who had served even as long as

thirty years should not be summarily dismissed

without a pension. Though we are tempted to admire

any one who practised economy in these extravagant

days at the French Court, the economy of Berryer was

misplaced. He reduced expenditure on the navy with

such effect that the navy almost ceased to exist.

When,

therefore, early in 1760, Berryer wrote to Levis

words of pious exhortation we know that Levis had

not much to expect that would be effective. The

King, said Berryer, counted on the courage, zeal,

and experience of Levis, and was sure he would do

his best. This was less encouraging than the

positive promises now made by Belle-Isle. The words

of Berryer were written six months before Levis

received them, but they show that he was justified

in expecting adequate and prompt help. Yet, in

reality, while Pitt was moving Heaven and earth to

make sure that his next blow should be final, France

did very little, and this little came too late.

Berryer was so indifferent to the real nature of the

crisis that the scale of his preparations was

ludicrously inadequate. We see to what depths

France's naval power had fallen when we learn that

she had no frigate of her own to send to Canada and

that she was obliged to purchase one from a private

owner. The frigate was the Machault (it had, at

least, a good name), the private owner was Cadet,

the high priest of corruption in Canada; and we may

be reasonably certain that not the King but Cadet

profited by the deal. Some legal obstacles were put

in the way of securing the services of a crew for

the frigate, and there was interminable delay. As

late as on April 4, 1760, long after Pitt had the

fleet for Canada at sea, the President of the Navy

Board is pained to hear that the Machault with the

unarmed ships that were to accompany her has not yet

sailed. On April 25 he learns that the convoy had

left Bordeaux some days earlier. Two English

frigates encountered the Machault. In the end she

escaped from them. But before she could arrive at

her destination three powerful British squadrons

were already in Canadian waters and were joyfully

looking for the arrival of the French squadron as

their prey. |