|

If

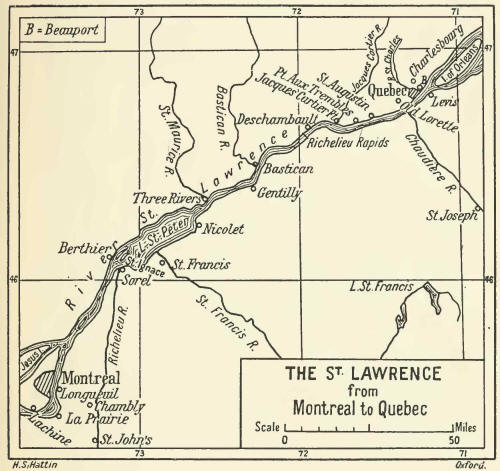

the British supposed that an overwhelming naval

force at Quebec would cause the French to lay down

their arms at once they were mistaken. Levis could

retreat safely to the interior, and he believed that

the difficult navigation of the St. Lawrence would

protect Montreal from attack by the fleet. Since the

incoming ships brought no strong addition to the

land forces, Levis was quite able to cope with the

army at Quebec. Only when the fleet should move

would he be in real danger. He found it impossible,

however, to keep his army together at one point, for

scarcity of provisions followed by desertion would

then be inevitable. Accordingly he distributed his

battalions even more completely than they had been

distributed during the previous winter. He kept a

force of 400 men at Pointe aux Trembles to watch the

English, 300 at Jacques Cartier, and 1,100 farther

up the river at Deschambault. Bougainville remained at Isle aux Noix to check a British

advance on Montreal by way of the Richelieu River. Far above Montreal on

the St. Lawrence, Fort Levis would, it was hoped, block the advance of

the British down the river should they try to come by that route.

In the losing battle now to be fought Levis

was at his best. He had not the slightest hope of succour. His own

military reputation, however, and his chances of promotion in Europe

depended on his holding out as long as possible. The army was only

half-fed and not half-equipped. Assuredly no one who had seen its panic

flight on May 17 would have supposed that it could hold out for nearly

four months still. The officers bore, without much complaint and with

the greatest courage, the terrible fatigue and the starvation which the

campaign involved. Their only hope was that peace might be made before

they should be obliged to lay down their arms. It was almost a matter of

life and death to them that this should be the course of events. If they

surrendered, the conqueror would undoubtedly insist that they should not

serve again during the. war. This might mean that they would be idle for

years, lose all chance of promotion, and starve on the slender half-pay,

or perhaps less, which they would receive from the Court of France.

Accordingly the French longed for peace

and made themselves believe that it was near. Malartic, the French

officer who remained in charge of the French sick at Quebec after the

retreat of Levis, offered to bet Murray that peace would be made by

August. On the British side there were no illusions as to the imminence

of peace, and Murray told Malartic that he would lose, since peace was

not to be hoped for that year. The British general knew something of the

resolve of Pitt to bring France low before he treated with her. But the

French leaders thought with Malartic. Their letters at this period are

full of assurances that peace is near. Those of Vaudreuil glow with an

abounding optimism based chiefly upon his own predictions. Writing on

May 24, 1760, only a few days after the French flight from Quebec, he

declares that the bearing of the British shows depression of spirits,

and that this must be due to some disaster to their cause in Europe

which they are concealing. Still whistling to keep up his own courage,

he wrote on June 1 to Colonel Dumas: 'Canada is drawing near to the

close of her suffering and misfortunes, so everything calls us to

increase our efforts that we may not lose the fruit of the negotiations

which are certainly under way to effect peace.' On June 3, to make

public these cheering hopes, he issued a proclamation to the Canadians

describing recent, but imaginary, French successes in Europe, and adding

that, as a consequence of the

French victory at Ste Foy, the King

of England cannot possibly avoid acquiescing in such terms as our

monarch shall prescribe to him; . . . the colony is nearing the

conclusion of its distress and difficulties.' Even Bigot, a keen man of

business, tried to explain the absence of help from France as wise

economy; so assured was an early peace that the French Ministry had

found it really unnecessary to send new forces to Canada. Levis himself

felt certain that the news of the defeat of April 28 would convince the

British that Quebec had fallen and would lead them to conclude peace at

once. Little did the French understand either the character or the

resources of those they were fighting.

If the French leaders were still

optimists, some of their men were not. Levis, indeed, says that the men

who remained with his force showed a cheerful courage ; but there were

many who did not remain. Some of the regulars had married in Canada,

intending to settle finally in the country when the war was over. Now,

despairing of the lost cause, a good many of these men deserted. The

movement to desert was much more general among the Canadians. They went

off in droves. On the whole they had fought well. Some of the French

officers, indeed, speak ill of their Canadian allies, but the truth

seems to be that they had been useful in a somewhat irregular way. They

did not fight well in the open. But their patience, their activity,

their hardiness made an officer on the French side call them the best

militia in the world.1 When, however, the French had retired from before

Quebec, the Canadians seem to have concluded that the cause of France

was finally lost. They were acute enough to know that, if the struggle

was to be prolonged, it would not be on their account, but on that of

the French officers, thinking of their own military careers in Europe.

Accordingly, with or without leave, the Canadians trooped away to their

homes. On May 21, Levis wrote in his journal that nearly all the

Canadians had left him, and that the officers, instead of checking their

men, had set them a bad example. The Canadian militia consisted chiefly

of farmers. They were sorely needed at home in the month of May, and

this excuse was urged on their behalf. When the French officers would

have dealt sternly with the deserters, and made threats of wholesale

executions, Vaudreuil, as we have seen, would not allow this severity.

The Governor's boast of what he could do with his 'brave Canadians' had

become a byword in the army. He was always sure that, when really

needed, they could be relied upon; he understood the difficulties of

their position and protected them from the consequences of military law.

The uncertainty and misery of a hopeless

campaign were prolonged by the inactivity of the British. They lingered

at Quebec and showed no signs of a forward movement. Murray was, in

truth, waiting for more troops and for the development of the campaign

against Montreal by the deliberate Amherst. Meanwhile, day by day, the

forces of Levis in the interior were being reduced to a pitiable

condition. Perennial famine haunted the French camps. As the summer wore

on, Levis wrote that he would soon have nothing but bread for the

troops, and that it would not be easy to get even bread. He cast longing

eyes on the maturing harvest, but he could not forbear asking whether

the French would be there to gather it. So many officers had died, or

had been wounded or made prisoners, that Levis had not enough to do the

necessary work. Daily the equipment of the army grew worse. Little

powder was left, and the artillery was so hopelessly weak that it was

impossible to defend effectively points on the river where otherwise it

would have been easy to harass, if not to check, the advance of the

British ships. The army was short of both muskets and bayonets. 'The

troops, except [the regiments of] La Sarre and Royal Roussillon, are

entirley naked,' wrote to the Minister of War on June 28. Some of the

men, of course, marched barefoot. The destruction of boats, when Levis

began his retreat, proved a disaster of great moment, for, though urgent

efforts were made, it proved impossible to replace them. The lack of

boats meant that the return towards Montreal must be made by land only,

and this worked a double evil. It led the troops through the Canadian

villages, where they committed depredations on the inhabitants, and it

added to the difficulties of movement, for there were few bridges, and

boats were necessary to cross the rivers. With only a few carpenters

left, Levis could build hardly any new boats. To take their place his

men constructed rafts which proved an unstable means of transport for

troops and stores across the swift Canadian streams.

By June Levis had learned that France had

refused to honour the drafts on her treasury made from Canada in 1759.

This spelled ruin for nearly every one concerned. Even the officers of

the regular army had been paid in these drafts. They had borrowed money

upon them and would now be overwhelmed with debt. Levis issued a private

circular letter to the commanders of battalions telling them what had

happened and outlining a plan for appealing to the King to meet at least

the drafts for the pay of the soldiers. But the Canadians, too, would be

ruined by the action of the Court. Soon the French leaders found that

the failure to redeem the ordinances was fatal. France had no longer any

credit in Canada. Already the peasantry had more than enough of nearly

worthless paper, and yet the French army was without other money for

purchases. The leaders were obliged to pledge their own credit for the

supplies to be furnished to the troops. But, with a failing cause, this

still proved poor security, and usually supplies could be obtained only

under compulsion. When this failed, even officers sold their clothing

for food. Meanwhile Vaudreuil's wordy optimism never slackened, and

Bourlamaque indulges in a little chaff at 'the long and fastidious

dissertations of the personage'. Levis was not so hopeful; he admitted

that he had no means of checking a fleet of frigates and transports in

an advance to Montreal, and that to meet this advance the French would

have to abandon their frontiers. But he wrote simply: 'We shall use

every means to save the colony, though our situation is so frightful

that only a miracle can do it. . . . It is necessary to finish this

business with honour and to delay the loss of the colony as long as we

can.' He kept himself busy inspecting the danger-points, and his

observations led him to conclude that the English would soon have 40,000

men in the heart of Canada.

A momentary gleam of hope cheered the

French when news came that their fleet, so long hoped for, had reached

America. Protected by the frigate Machault, the little convoy had left

Bordeaux on April 10, and had taken more than a month to cross the

Atlantic. On May 14 the Machault captured, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,

a British ship, and learned from her that a British fleet had already

ascended the river. This was grave news, and a council of war decided

that the French ships should take refuge far up the Bay of Chaleur at

the mouth of the Restigouche River. Here they would have the help of

about fifteen hundred Acadians expelled a few years earlier from their

homes in Nova Scotia. On arrival the French sent word at once to

Montreal. ' In the night', wrote Levis in his journal on June 13, 'we

received news from France by a courier sent from Restigouche in Acadia

where our ships destined for Quebec had stopped.' He adds, with a touch

of bitterness, 'They started . . . just when they should have been

arriving.' Vaudreuil was highly excited by the long-looked-for

intelligence which had come, of course, overland. ' At last', he wrote,

' we have the news from France which we have so long desired ; what a

pity that the ships which brought the news did not come earlier ; we

should now |Kve been entirely at our ease. . . . The letters which I

have received from the Minister assure me . . . that we shall have peace

towards the middle of the campaign.' He concludes, with his usual

irresponsible optimism, that the British cannot possibly send any

further help to North America, and that France is about to make in

Europe the most potent efforts to crush her enemy.

The arrival of the French convoy did not

disturb the plans of the British or arouse in them anything but

exultation. British commerce had suffered much from French privateers.

During the war more than two thousand British ships were captured by the

French, while the British took less than half that number. Even in the

year 1759, so disastrous to French power on the sea, the French had

captured 812 British vessels. The explanation is that British prey was

abundant, for, unlike the French, the British had a vast sea-going

commerce which offered easy conquests to privateers. It was the parallel

of the situation during the civil war in the United States, when the

South, with almost no ships on the sea, was able, by means of a single

privateer, the Alabama, to inflict ruinous loss on the extensive

shipping of the North. The French had managed to take a good many

vessels laden with stores for Quebec. Le Blanc, a much-dreaded

privateer, had haunted the waters near the mouth of the St. Lawrence and

inflicted heavy loss on the trade of the British colonies. Now the time

had come for the British to ruin what remained of French naval power in

America.

When news of the arrival of the Machault

and her convoy reached Halifax and Quebec, a squadron set out from each

place eager to be the first to deliver the crushing blow. Captain Wallis

left Quebec, with five ships ; Captain Byron, grandfather of the poet,

left Halifax, also with five ships, himself leading in the Fame. Fortune

favoured Byron's squadron. The Restigouche River empties into the Bay of

Chaleur, a long and narrow arm of the sea. The upper waters of the Bay

are so shallow as to be hardly navigable for large ships. The French

convoy consisted of the frigate Machault, of thirty guns, two large

store-ships, and some twenty smaller vessels, most of them prizes taken

off the coast of New England by the enterprising Le Blanc. The French

had pushed up the Bay to a point where the shallow water seemed a

protection against the great British fighting ships.

Captain Byron, parted from his other

ships by bad weather, arrived at the Bay in the Fame five or six days

before they came up. His first exploit was to capture an armed schooner,

but her forty-seven men escaped to the shore. Afraid to take his large

ship up the Bay, he anchored and sent boats some dozen miles farther to

learn where the French lay. Though the channel proved to be extremely

narrow and difficult, he resolved, in the end, to bring up his own ship.

The attempt nearly proved fatal; he ran aground and for a time was in

imminent danger of being boarded by the French. But after nine or ten

hours of hard work he was again afloat. His other ships now appeared,

but two of them ran aground before they could reach him. The Repulse and

the Scarborough were, however, able to come on, and they and the Fame

advanced up the narrow channel which the French had tried to block by

sinking some ships. In spite of grounding a dozen times, the Fame at

length opened fire on a shore battery. Its defenders ran away at once,

and the British then landed and not only destroyed the battery but set

fire to the adjacent village of Restigouche containing some two hundred

wooden houses.

The French frigate and transports were

still out of reach, pressing farther and farther up the Bay, but, as the

British observed, running often aground. By lightening two of his

frigates as much as possible, he was able to follow the enemy, and, in

the end, he came within range. Then followed a duel between the British

ships and the French frigate, which lay close to a shore battery. The

duel lasted for two or three hours. The French fought well and were

determined that the frigate should not fall into the hands of the

British. The day went against them. They abandoned the Machault after

taking off the wounded and setting her on fire. The British took, in

all, twenty-two vessels, laden with cargoes valued at not less than two

hundred thousand pounds. Even in these ships was evidence of the

profound corruption which affected Canada : horseflesh and putrid meat

had been sent out. The British removed from the store-ships wine,

brandy, and all else of value, and then burned the whole convoy. It was

a disastrous end of France's effort to aid her perishing colony. The

losses on the British side were only four killed and nine or ten

wounded, while the French had about thirty casualties. The British did

not take a single prisoner, for the French crews landed and escaped. As

Byron's victorious squadron came down the Bay, he met Captain Wallis,

just arrived with his squadron from Quebec and eager for a share in the

struggle. He had, however, come too late and could only turn back to

Quebec with the news of one more British triumph over the French upon

the sea.

Meanwhile Murray had been making himself

secure. He obliged the Canadians to level the works which Levis had

raised to menace Quebec, and he warned them by proclamation to expect

rigorous treatment for any acts hostile to the British. It was no empty

threat. On May 29 Murray seized, in the parish of St. Michel, on the

south side of the river, a captain of militia named Nadeau. After taking

the oaths exacted by Murray, this man had joined and induced others to

join the army of Levis, and now Murray caused him to be hanged in his

own village.

Soon after the retreat of Levis, Murray

drew up his army outside the walls of Quebec. It was, in truth, rather a

pitiable array, for of the seven thousand left in the previous autumn

only about fifteen hundred men were now left fit for duty. But Murray

told them that their task was nothing less than the total conquest of

Canada. They faced it cheerfully enough. Hundreds of worn, sick men were

eager to take their places in the ranks as soon as possible. Murray sent

invalid soldiers to the Island of Orleans to recuperate ; for invalid

sailors the church at the Point of Levy was turned into a hospital.

Great tasks still awaited the army. When,

on May 30, the British had held a solemn thanksgiving service in Quebec,

their gratitude had sprung as much perhaps from a lively sense of

triumphs to come as of those already attained. But waiting had proved

necessary. The British Ministry had decided, early in 1760, that the

former French stronghold of Louisbourg in Cape Breton should be totally

destroyed. Even the harbour was to be so ruined that never again could

it be useful to an enemy. The destruction would release the considerable

garrison still holding Louisbourg, and a good many of these troops were

to be sent to help Murray. But to destroy the massive works at

Louisbourg took time, and aid to Murray was long in coming. Time was

also required for the recovery of the sick at Quebec, and for the

deliberate Amherst to begin his advance on Montreal. Murray chafed under

the delay and cursed Amherst's slowness; Malartic, who sat at Murray's

table, declares that he heard Murray, in his usual impulsive and

somewhat extravagant style, threaten to hang some of his officers who

were trying to justify the impassive deliberation of the

Commander-in-Chief. Not for two months after Levis retired could Murray

begin to advance on Montreal. The French thought that the long delay was

part of a deep-seated plan to advance when the harvest was ripening and

when the Canadians would wish to remain at home to gather it.

Murray's forces were in motion before the

news of the destruction of the French squadron reached Quebec. Amherst

had mapped out a complete plan of campaign, and this plan Pitt had

studied and approved. We know that, during these strenuous days of war,

Pitt worked with fiery energy and so devoted himself to his tasks that

he gave up even the usual attendance at Court. Nothing is more striking

than the precision in regard to detail of this great minister who was

carrying on a world-wide war and might well have left detail to the

professional military man. He knew, however, that in military operations

detail is everything. He must have studied closely the existing maps

which showed the situation in America. The generals send him diaries of

their doings and he follows their movements. The situation of every

obscure post is clear to him. He knows where boats will be needed and

writes anxiously to Amherst to make sure that those used in the previous

year are being properly cared for and that the building of new ones is

looked after. He knows what dangers lie in the path of British success

and points them out clearly. But he rarely finds fault and he never

scolds. He chose men whom he could trust and he trusted them. He was not

superior to the popular view that France was England's natural enemy,

and he exulted in her disasters. When, in November 1759, Hawke delivered

his crushing blow to the naval power of France, at Quiberon Bay, Pitt

wrote to Amherst a glowing account of the 'signal and glorious success'

and of 'the consternation and dejection' of the enemy. He was resolved

so to prostrate France that never again could she assail England.

British defeats and victories stirred his deepest emotions. With Wolfe's

victory England, as a whole, had dismissed Quebec from its mind. That

game it thought was won. But, until France's power in America was

completely crushed, Pitt was anxious. The defeat of Murray on April 28

filled him with sadness, the retreat of Levis, not many days later, with

joy. ' Join, my love,' he then wrote to his sister Hester, ' with me in

most humble and grateful thanks to the Almighty. The siege of Quebec was

raised on the 17th of May, with every happy circumstance. The enemy left

their camp standing, abandoned forty pieces of cannon, &c. Swanton

arrived there in the Vanguard on the 15th, and destroyed all the French

shipping, six or seven in number. Happy, happy day ! My joy and hurry

are inexpressible.'

With such a leader the generals in

America were bound to plan something far-reaching. All through the

winter, Amherst, stationed at New York, had been busy with the bringing

together of an army so great that the result could not possibly be

doubtful. It is amazing that New France, with her scanty population,

should so long have fought the British. Her peasantry, however, were

organized into a very effective militia, they were accustomed to

despotic leadership, and they did what they were told. New France was

united. The British colonies, on the other hand, were divided. They were

jealous of each other and of their own independence. The citizen farmers

coming together in their dozen legislatures were somewhat prone to stand

by their own views of the problems of an Empire and to reject the

insistent urgency of Pitt. For the most part the colonial levies raised

for the campaign of 1759 had been disbanded and had returned to their

homes. To secure new levies

Amherst must correspond with each

governor. The governor must, in turn, lay the general's demands before

the legislature of his province. The talk of peace which the French so

persistently indulged in was common also among reluctant legislators as

an excuse for inaction. But the zeal in some quarters was admirable.

Massachusetts, under her enthusiastic Governor, Pownall, one of the most

ardent Imperialists of the eighteenth century, led the van and made

promise of help so generous that Pownall was able to write: 'It has been

hitherto the Merit of this Province to stand foremost in the King's

Service but here they stand alone.' Massachusetts was to put 2,500 men

in the field, New York promised 2,680, New Hampshire 800, and so on. The

remoter colonies were less zealous. The Legislature of Pennsylvania

insisted that, whatever the menace to other colonies, Pennsylvania was

in no danger, and, in spite of Amherst's protests, the colony would

promise only 150 men.

In 1900, when the British colonies sent

contingents to South Africa, the mother country paid and equipped the

regiments. In 1760, the colonies did better, for they undertook not

merely to muster but also to clothe and pay their men. Arms, ammunition,

tents, and food were, however, to be supplied by Great Britain. Pitt

wrote somewhat peremptorily that the King expects and requires colonial

help; yet he promised that the colonies might be compensated by the

British Parliament for their outlay. In the end they put into the field

what were for them considerable armies, and to do so they incurred heavy

financial obligations. But, of course, they were carrying on a war at

their own door and for their own safety.

Pitt had urged Amherst to be ready by the

first of May to begin his campaign. The colonial levies were, however,

not to be hurried. Amherst left New York on May 3 to proceed up the

Hudson River, and, by way of Albany and Schenectady, to advance

ultimately to the shores of Lake Ontario. Three armies were to close in

on Montreal, one from the east, one from the south, and one from the

west. The French could not break through the cordon which surrounded

them, and they must either surrender piecemeal or be driven in upon

Montreal. We may surmise that a single army advancing on Montreal in

great force by way of the St. Lawrence would not have proved less

effective. A slow enveloping movement was, however, in accordance with

Amherst's deliberate and thorough methods. He took one great chance—that

the British fleet would reach Canada before the fleet from France. Had

this not happened, had the French recovered Quebec and been able to hold

it, Amherst's attempt on Montreal might well have proved disastrous.

Bourlamaque, perhaps the ablest officer on the French side, calls the

advance by way of Lake Ontario a foolish chase, and says that Amherst

undertook it only to prove that if Montreal had not fallen in the

previous year it was not his fault but Gage's.

Plans on paper, made remote from the

scene of action, can very rarely be carried out. This plan, however,

worked admirably. Since Amherst had blamed Gage for his failure to clear

the Upper St. Lawrence of the French, he now undertook this task

himself. His delays were many. Not, as had been hoped, in May, but in

July, some ten thousand men were laboriously advancing through the

wilderness from Albany to Oswego, not far from the point where Lake

Ontario discharges into the St. Lawrence, there to embark and descend

the great river to Montreal. At the same time more than three thousand

men, under Colonel Haviland, were to advance by Lake Champlain, the

route which Amherst himself had used in the previous autumn. Haviland

was to keep the French at Isle aux Noix in a state of constant alarm and

thus conceal the chief menace, which was from Amherst's overwhelming

force. A third army, under Murray, was to advance from Quebec. The

movements were so planned that the three forces should arrive before

Montreal at the same time.

It was Murray's advance that the French

leaders watched most anxiously. The really decisive movement was,

indeed, that of Amherst ; but Amherst, far up in the wilderness of the

interior, could not be watched, and only vague rumours of what he was

doing reached the French. They now knew that if the British should

decide to take a fleet up the river they could do little to stop them.

An army they were ready and more than willing to fight, but a fleet they

could only watch impotently from the shore. Murray intended simply to

ignore the French land forces. He was safe on the ships. If the French

wished to remain in his rear they were free to do so, for, should

Montreal fall, any further efforts to hold Canada must collapse. Murray

hoped that the French would surrender to him before the advance began.

'He wished, I think, to pump me this morning,' wrote Malartic to Levis

on May 26 ; 'he asked me what you intended to do, and said that it was

impossible for you to save the colony. You would only ruin it by holding

together your army.' Murray told Bellecombe, a French officer at Quebec,

that he would grant easy terms if the French would capitulate. When

Bellecombe answered with some spirit that the English would have to do

some more fighting before they took Canada, Murray retorted that the

French army could not live on air. The French were, however, able to

keep up a long, losing campaign, and the war could be ended only by an

elaborate campaign.

Murray managed so to keep in touch with

Amherst's plans that he knew the proper time to set out. In the end he

started without waiting for the reinforcements from Louisbourg. They

would, however, follow him quickly. Colonel Fraser was to remain in

command at Quebec, and both Murray and his second in command, Colonel

Burton, were to go up the river with the army. Officers and men who had

gone toNew York and elsewhere to recruit their health now returned. Some

others were able to leave the hospitals at Quebec. But three thousand

sick and wounded remained, and, in the end, Murray could array for

active service only about twenty-five hundred men of all ranks. Officers

and men, really too ill for such service, none the less begged to be

allowed a share in the final glory of the conquest of Canada. They had

borne, they said, the burden and heat of the day, and now, it seemed,

they were to be left at Quebec and deprived of their reward; the glory,

due to them, others would secure. But Murray was firm and gave strict

orders to his officers not to take with them any one unfit for full duty

in the field. So insignificant seemed the French power for attack that

Quebec was left defended by only 1,700 men fit for duty; but, of course,

some ships remained, and, in case of need, others could hurry down the

river to the rescue.

On July 11 the baggage of the troops was

put on board the transports. Levis, with his army half starving, heard

with hungry desire that the British were taking a prodigious quantity of

food supplies. On the 12th Murray reviewed his force. Next day at five

o'clock in the morning the right brigade embarked and at five in the

afternoon the left did the same. The men had just received a part of

their pay, long overdue, and had been guilty of some irregularities,

but, in spite of this, the embarkation was made in good order. At three

o'clock on the next morning, the 14th, everything was ready ; the fleet

weighed anchor and began its momentous advance. The array on the St.

Lawrence was imposing. Four British men-of-war provided the escort. The

men-of-war, floating batteries, and transports, made up a fleet of some

eighty vessels. Considerable fleets had often sailed up as far as

Quebec, but this was the first time that one had set out to attack

Montreal. The array made a profound impression upon the people who

surveyed its advance from the shore. ' The habitants are frightened to

death at the sight of the fleet,' wrote Levis on August 7; 'they are

afraid that their houses will all be burned.' Some of them already knew

by experience what the British could do in this respect.

On the first night the fleet anchored

opposite Pointe aux Trembles. On the 15th it was before Jacques Cartier,

the stronghold which the French had held during the winter. The fort

stood on a bold eminence, and an abattis of felled trees, stretching

down to the water, made assault from that side almost impossible. The

garrison fired some shot and shell at the ships. But the channel was far

away, near the south bank, and the fleet passed on untouched, leaving

the fort in the rear. Murray now showed that he intended to do precisely

what Levis most dreaded—to advance to Montreal without attempting to

fight on land. Dumas, who commanded at Jacques Cartier, was instructed

to follow Murray up the river. ' If the enemy', Vaudreuil had written,

'should decide to penetrate to the heart of the colony and to leave you

where you are, you will not hesitate, in such a case, to withdraw your

outposts, to summon the militia of your neighbourhood . . . and to

proceed to join M. de Lon-gueuil and the forces which he will have

assembled at Three Rivers.' Vaudreuil added that if the British should

try to land at Three Rivers they were, in his accustomed fine phrasing,

to be resisted even at the cost of the total annihilation of the French

defending force.

The British rarely ventured to land on

the north shore, but on the south they repeatedly threw out parties of

rangers. This was a challenge to the Canadians. However weary they might

be of the contest, they could not refrain from the guerrilla warfare in

which they excelled. Now they had an occasional brush with the British.

Sometimes the rangers marched on shore for days together, advancing with

the fleet. On leaving Quebec Murray had issued a proclamation saying

that Canadians who laid down their arms had nothing to fear. He required

only an oath of neutrality. On July 25 Captain Knox describes a scene

that was often duplicated:

'The parish of St. Antoine have this day

laid down their arms, and taken the oath of neutrality; as the form of

swearing is solemn, it may not be improper to particularize it. The men

stand in a circle, hold up their right hands, repeat each his own name,

and then say,—

' ... Do severally swear, in the presence

of Almighty God, that we will not take up arms against George the

Second, King of Great Britain, &c., &c., or against his troops or

subjects; nor give any intelligence to his enemies, directly or

indirectly ; So Help me God.'

The oath was mild enough and Murray

insisted that it should be scrupulously observed. From time to time he

himself went ashore. Since he knew French well he could speak to the

people in their own tongue. He told them that, while the cause of France

was hopeless, the might of Britain as shown in her ships, artillery, and

other equipment was resistless. He added that he would in no way molest

the persons and property of the men who were attending to their duties,

but that he would burn all the houses from which the men were absent.

This resolution caused extensive desertions from the French army. Many

of the militia returned to their parishes in order to avert the

destruction by the British of their houses, should they not be there. In

village after village the whole male population took the oath, saying,

in some cases, that they were glad to have the excuse of Murray's demand

for so doing.

Some Canadians, however, showed

irreconcilable hostility, and Murray blamed the clergy for this

attitude. To a priest brought before him he said: 'The Clergy are the

source of all the mischiefs that have befallen the poor Canadians, whom

they keep in ignorance, and excite to wickedness and their own ruin. No

doubt you have heard that I hanged a Captain of Militia ; that I have a

Priest and some Jesuits on board a ship of war, to be transmited to

Great Britain: beware of the snare they have fallen into ; preach the

Gospel, which alone is your province.' Early in the advance up the river

the French sent a party of Indians to the south shore to harass the

British with their barbarous methods of warfare. The result was a stern

message from Murray, sent under a flag of truce to the officer

commanding at Deschambault, that if the savages were not instantly

recalled, and if they committed any barbarities, no quarter would be

given even to regulars and that the country would undergo military

execution wherever the British landed.

Along the river the houses were numerous.

'From the Island of Coudre,' says Captain Knox,' below Quebec, to that

of Montreal, the country on both sides of this river is so well settled,

and closely inhabited, as to resemble almost one continual village ; the

habitations appear extremely neat, with sashed windows, and, in general,

washed on the outside with lime, as are likewise their churches, which

are all constructed upon one uniform plan, and have an agreeable effect

upon the traveller.' When the British landed and entered the houses

which, from the river, looked so charming, they suffered disillusion,

for the peasantry were, Knox declares, ' intolerably dirty'. As the

fleet advanced farther from the regions about Quebec desolated by war,

the condition of the people improved. ' I have been in a great many

farm-houses since I embarked on this expedition,' says Knox, ' and I may

venture to advance, that in every one of them I have seen a good loaf,

two, or three, according to the number of the family, of excellent

wheaten bread ; and such of the inhabitants as came on board our ships,

from time to time, in order to traffick disdained our biscuits, upon

being offered refreshments. . . . Notwithstanding all that has been said

of the immense distresses and starving condition of the Canadians, I do

not find that there is any real want.'

Black cattle, sheep, and pigs seemed

numerous, and sometimes this plenty was too great a temptation to the

British seamen allowed to go on shore. On one occasion they pillaged

houses and offered violence to some Canadian women. The result was a

stern threat from Murray that death by hanging would be the penalty for

a repetition of the offence. The men had more innocent diversion in

fishing and in paddling the Canadian canoes. To the British sailor these

were a great novelty. He knew little of their use and would sometimes

stand up in them to fish, with the inevitable result of an upset. The

current was very swift and a good many soldiers and sailors were drowned

as a result of their own carelessness.

The point on the river probably most easy

of defence was Deschambault, some nine or ten miles above Jacques

Cartier. There the Richelieu Rapids made passage difficult, for the

channel was shallow and full of rocks, which at low tide appeared above

the surface. Powerful batteries at this point could have checked an

ascending fleet. Murray had, indeed, planned to seize this place in the

spring so as to make impossible the further ascent of French ships which

might reach Quebec.1 The French had placed a battery in the church at

Deschambault, and this began to play on the British ships as they tried

to work their way up the channel. Adverse winds helped the French to

delay for about ten days a part of the fleet. A lieutenant and three

privates were killed by their fire. But, owing to bad powder and to bad

guns, the resistance was really weak, and when, on the 26th, there was a

favourable wind, the fleet sailed on without further injury. At no other

point on the river had the French the slightest chance of retarding the

British advance. Indeed, though the ascent of the St. Lawrence involved

difficult and intricate navigation which taxed the skill of Captain

Deane, the officer in command, not a single ship was lost or even

damaged during the entire journey.

Day by day as the fleet advanced it was

'politely attended', as Knox expresses it, by a French force which

marched along the north shore abreast of the ships. The French feared

that the British would try to land at Three Rivers, the most important

place in Canada, after Quebec and Montreal. Here M. de Longueuil was in

command, and he with Pontleroy, the engineer, had long been busy

preparing for defence. It was the capital of one of the three

subdivisions of Canada, and the French considered it a garrison town of

great importance. Knox, however, calls this 'open straggling village' a

'wretched place', and notes with satisfaction that part of it lay so low

on the north shore as to be an admirable object for bombardment. He saw

what strikes visitors to French Canada to this day : the poor wooden

houses of the inhabitants in vivid contrast with the massive stone

church and convent buildings. The place was defended by extensive

entrenchments and redoubts, 'indicating', as Knox says, 'an intention to

have disputed every inch of ground with us, if we had made a descent

there, which it may be presumed they expected.' It was here indeed, that

Vaudreuil had said that rather than let the British land the French must

die to the last man. But the British had no thought of landing. The

Canadians, as distinguished from the French, invited them to do so in

what seemed no unfriendly way. When some armed British boats went

forward to examine the channel before the town, a body of Canadians

drawn up on the bank called out to them, 'What water have you,

Englishmen? 'The reply was given with true British brusqueness:

'Sufficient to bring up our ships, and knock you and your houses to

pieces.' The answer of the Canadians showed the temper to which some o.

these unfortunate people had now come. A man, supposed by the British to

be an officer, called out that the Canadians, if left alone, would offer

the British no annoyance, and ended by inviting the officers to come

ashore and refresh themselves.

Two channels led past Three Rivers, that

near the north shore commanded by the batteries of the town, that on the

south side out of range. The ships passed quite safely by the south

channel. The day—the 8th of August—was clear and pleasant, and Captain

Knox, who had an eye for beauty, thought that the ' situation on the

banks of a delightful river, our fleet sailing triumphantly before them,

in line of battle, the country on both sides interspersed with neat

settlements, together with the verdure of the fields and trees,

afforded, with the addition of clear pleasant weather, as agreeable a

prospect as the most lively imagination can conceive'. The French

troops, who seemed to number about two thousand, lined the works as the

British ships filed past. 'Their light cavalry, who paraded along shore,

seemed to be well appointed, clothed in blue, faced with scarlet ; but

their officers had white uniforms.' Knox, aided by a glass, discerned

among the troops fifty naked savages with painted faces. Even at this,

the most carefully defended spot on the river, the French could only

stand impotent on the bank and see the hostile fleet pass. It mattered

nothing to the British that Three Rivers, like Jacques Cartier, was left

in their rear, untaken. Even its defenders soon abandoned it to march

along the north shore in the wake of the advancing fleet.

When the fleet reached Sorel at the mouth

of the Richelieu River, a new embarrassment appeared for the French

defenders. Haviland was advancing down Lake Champlain to the head of

this river. Would Murray try to ascend the river and catch as in a vice

the fort at Isle aux Noix, which would be assailed at the same time by

Haviland from the south? This was what the French most dreaded and what

they were resolved, if possible, to prevent. Bourlamaque,

now in command at Sorel, was puzzled.

Levis was moving from post to post and the couriers were kept busy. Even

though paper was now hardly to be had, Bourlamaque sometimes sent to his

leader three letters in a single day. On August 12, impotent on the

shore at Sorel, Bourlamaque watched the long array of ships file past.

It was useless to fire upon them, he said, as he could do no real

damage. ^ He could only count the ships, and write to Levis how many

there were : five ships with three masts, nineteen with two, ten with

one mast, twenty-one armed bateaux, and a seemingly endless number of

smaller craft. What should he do ? he asked. He could not for ever keep

marching his barefooted men along the shore to points where the English

might possibly land. He had only seven hundred troops, and three hundred

and fifty of them were militia, not well-disposed. He had no one to look

after the stores, no secretary even for the necessary clerical work, no

smith to repair damaged muskets. If he had had one or two naval officers

they could have told him what to expect from the movements of the

British ships. 'I am worn out, I have no one on whom I can depend, I can

get no sleep,' he wrote.

It is interesting to contrast with this

despairing utterance the thoughts of the British officer, Captain Knox.

On this same day, August 12, Knox describes in glowing terms the scene

which he surveyed as the ship approached Sorel :

'I think nothing could equal the beauties

of our navigation this morning, with which I was exceedingly charmed ;

the meandering course of the channel, so narrow that an active person

might have stepped a-shore from our transports, either to the right or

left ; the awfulness and solemnity of the dark forests with which these

islands are covered, together with the fragrancy of the spontaneous

fruits, shrubs, and flowers; the verdure of the water by the reflection

of the neighbouring woods, the wild chirping notes of the feathered

inhabitants, the masts and sails of ships appearing as if among the

trees, both a-head and a-stern . . . formed, all together, ... an

enchanting diversity.'

There were other things to please a

British officer, for while the fleet lay before Sorel it was joined by a

second squadron bringing two regiments from Louisbourg, long expected by

Murray. Lord Rollo, its leader, had not tarried at Quebec, but had

hurried up the river to join Murray's expedition. Opposite Sorel is the

island of St. Ignace, and here the troops were landed that the

transports might be cleaned and aired. The strip of water separating

them from the mainland was an adequate protection from attack. Since the

male Canadians seemed to be absent serving with the French army, the

British took freely as the spoils of war what provisions they could find

in the houses.

The Canadians in this district had seen

as yet no real war, and they had not learned, what those near Quebec had

learned, how sternly the British would punish acts of hostility on the

part of the civil population. A church at Sorel had been fortified under

the direction of the cure, and many of the male inhabitants in the

neighbourhood were in arms. A stern lesson seemed necessary.

Accordingly, on August 22, about two in the morning, a British force

under Lord Rollo dropped down the river from the island of St. Ignace,

and, landing a little below Sorel, began the work of devastation. They

burned the houses of the men who were absent from home, but spared the

others. This destruction was the result of the same policy that Wolfe

had carried out near Quebec. 'I was . . . under the cruel necessity of

burning the greatest part of these poor unhappy people's houses,' Murray

wrote to Pitt; 'I pray God this example may suffice, for my nature

revolts, when this becomes a necessary part of my duty.' It was

effective' Bourlamaque wrote to Levis at six in the evening of that very

day: 'Protests and menaces are unavailing to keep the inhabitants of

this parish from giving up their arms to the English. At this moment

they tell me that twenty men of the company of Cormier are going off

with their muskets. I am writing to M. Denos to try to stop this by

announcing that I will burn down the house of the first man who does

it.' Fifty or sixty Canadians, sent from Montreal to take some vessels

down the river, abandoned them and ran off to their homes, and a company

of militia broke out into open pillage in their own camp. They declared,

says Rocquemaure, in command at St. Johns, that they would stay with the

French army as long as it suited them, some until Tuesday, some until

Friday, and that then they should go home. Since whole companies were

guilty, punishment was really impossible. It was useless, Bourlamaque

says bitterly, to write to Vaudreuil about any misdoings of the

Canadians. The Governor gave no heed, and would probably write to the

Court that Bourlamaque had two or three thousand Canadians who were

doing wonders. These poor people had meanwhile a hard fate. If they went

away from home the English burned their houses, on the supposition that

they were serving with the French; if they stayed at home the French

threatened to do the same thing, on the supposition that they were not

fighting for their country.

By this time Isle aux Noix had become

untenable. Already, on August 2, Bougainville, in command there, wrote:

'I expect the enemy to unmask to-morrow a great devil of a battery,

which is hardly a musket-shot from us. They have made immense abattis

... It doesn't matter: we shall do our best.' On August 9, three

vessels, representing the vanguard of Haviland's force, appeared before

the place, and soon shot and shell were pouring into it pitilessly.

Bougainville had done what he could ; he had made elaborate works and

entrenchments and had stretched booms across the two branches of the

river enclosing the island. But the British carried on a furious

bombardment, and they managed to work round with some mortars and cannon

so as to attack the fort from the rear. They pushed up their works so

close that they were able to kill soldiers on the ramparts with muskets.

Moreover Bougainville was likely before long to be face to face with

famine. The seven or eight oxen which he had were killed by the British

fire. The river was full of fish, but the British fire made it

impossible to resort to this source of supply.

Bourlamaque thought that Isle aux Noix

should be abandoned ; so did Vaudreuil; but Levis, who wished to prolong

the fight and to delay surrender, opposed retreat until the very last

moment. He ordered La Pause, an able and tactful officer, to send

forward, if possible, help to Bougainville from St. Johns, a few miles

lower down the river towards the St. Lawrence. On August 3 La Pause

could hear firing at the distant fort. It was raining heavily. The

Canadian scouts would not volunteer to carry dispatches to Bougainville,

and, in the end, Nogueres, an officer of the Royal Roussillon Regiment,

was obliged himself to undertake the task, and but one Canadian could be

induced to accompany him. On August 25 a critical event happened. The

British suddenly pushed forward some cannon and opened a hot fire on the

five French ships which lay at the foot of the island. The ships were

riddled by the fire. Some of the sailors escaped by swimming to shore,

the rest surrendered. After the protecting ships had been captured, the

British would soon break the boom, or at least carry across boats so as

to attack the fort from points below as well as above the island. They

could also go down the river and attack St. Johns and other places.

Levis was still most anxious to hold the fort. 'I count much on your

post', he had written on August 19 to Bougainville, ' to prolong our

defence and to do honour to our arms. The place could not be in better

hands.' Later he sent a verbal message through La Pause, at St. Johns,

that Bougainville should hold out. But Vaudreuil was of a different

mind. On August 26, when the news of the capture of the ships reached

him, he wrote to say that if Bougainville could not check the advance of

the British down the river, or if in danger of being captured he should

spike his cannon and retire. Levis, he said, knew the purport of his

letter. Bougainville was sorely puzzled what to do. He held a council of

war on August 27, and they reached a unanimous decision to retire.

This had become no easy task, for the

British were now encamped above and below the fort on both banks of the

river. Bougainville planned a ruse. While withdrawing his men he would

keep up the appearance of strenuous defence. Some forty invalids, under

a colonial officer, La Borgne, were to continue firing the seven or

eight pieces of cannon as long as ammunition lasted.. Meanwhile the

retreat would be effected. At ten o'clock at night all the available

boats were gathered at the chosen point and silently the garrison

crossed to the mainland. The plan succeeded. The British did not learn

of the retreat until noon the next day. Then La Borgne, who kept up a

vigorous fire, had no more ammunition, and he raised the white flag.

Meanwhile Bougainville was marching through the forest towards Montreal,

as he thought. He had counted on Indians as guides, but they had

deserted a losing cause, and, without guides, he lost his way. From

midnight to midday the army toiled through frightful swamps, only to

find in the end that it was still near the British camp before Isle aux

Noix. Bougainville now tried to reach St. Johns,, a few miles down the

river from Isle aux Noix, and at four in the afternoon his bedraggled

force arrived at a clearing not far from that place. 'I was so overcome

with fatigue,' writes the Chevalier Johnstone, who took part in this

terrible march, ' and so totally exhausted, not being able but with the

greatest pain to trail my legs, that I thought a thousand times of lying

down to finish my days ; but the fear of falling into the hands of

savages connected with the English, and the idea of the cruelties and

torments which they exercised over their prisoners, making them die

under the severest sufferings, at a small fire, . . . the terror of that

gave me from time to time new strength. ... I have very often found

myself in . . . painful and fatiguing positions but never in any where I

experienced so much suffering as in this cruel journey.' The weather was

very hot, and when he reached the river and had sufficiently recovered,

he plunged in, still wearing his uniform, and remained for more than an

hour with only his head above water. The French lost twenty-four men on

the march.

La Pause, at St. Johns, was distressed

when he heard of Bougainville's retreat. Since but few men had been lost

at Isle aux Noix, he thought that greater sacrifices should have been

made to support the glory of the French arms. Bougainville's answer to

these reflections was a demand to be judged by a council of war. La

Pause himself had now to retire, for no one at St. Johns, not even the

officers, wished to fight. He postponed his retreat to the last moment,

that he might help to rescue the poor fellows lost in the woods. But

when, on the night of the 29th, the British began an advance in force on

St. Johns, the French set it on fire and marched the dozen miles to La

Prairie, opposite Montreal. Misfortunes did not come singly. Just at the

same time word was received that Fort Levis, far up on the St. Lawrence,

had fallen to Amherst.

The Indians, alert to see how the wind

was blowing, were now treating independently with the British and

deserting the cause on which their own misdeeds had brought such

discredit. On September 2, Levis met some of them at La Prairie,

opposite Montreal, on the south side of the river. While he was

haranguing them a messenger arrived to say that the Indian tribes had

made peace with the British. At once the savage audience ran off without

listening further. The moment the Indians who had negotiated the peace

with the British had completed their work they gathered on the beach

opposite Montreal, and brandishing knives and hatchets and picked

war-cries in token that they had now become the enemies of the French.

The British did not find that their new allies mingled well with their

own savages. While Murray was occupied, apparently at Longueuil, with

the French Indians, two Mohawks entered the room. They gazed intently at

the others and then dashed at them with fury. When separated the two

groups continued to mutter reproaches and threats. The Mohawks recalled

outrages by their old enemies and swore that 'the cowardly dogs' should

pay for it. 'We will destroy you and your settlement, root and branch; .

. . our squaws are better than you ; they will stand and fight like

men—but ye skulk like dogs.' At this the French chief raised what Knox

calls 'a horrid yell'. Murray kept the peace only by threats of stern

chastisement from Amherst if any violence was done.

The French debacle was now almost

complete. Place after place near Montreal surrendered to the British.

Levis could not hold together his forces. ' The regulars now desert to

us in great numbers,' wrote Knox on September 3, ' and the Canadian

militia are surrendering by hundreds.' Those who did not surrender

deserted in bands and ran off to their homes. Even when they did not

desert they refused to obey orders. 'I gave orders to M. de Bellecour',

says Roquemaure on September 3, ' to lead his mounted men to Longueuil,

but not one would follow him. The militia attached to the Royal

Roussillon battalion refused to march.' Even the regulars went off half

a dozen at a time. The officers harangued the troops and appealed to

their honour, but with little effect. Everywhere was raised the cry for

'Capitulation'.

Meanwhile Murray was pressing up closer

to Montreal. By September 4 he had disembarked most of his troops on the

island of Ste Therese, near the lower part of the greater island on

which Montreal stands. ' From this point he could easily land in force

on either the north or the south side of the river. Haviland was

advancing steadily from St. Johns to Longueuil, immediately opposite

Montreal, and news had come that Amherst was near on the upper river.

The word now went forth on the French side that all the regiments should

close in on Montreal. Their forces on the south bank crossed the river

as best they could, and by September 3 the sadly diminished ranks of the

dispirited army had been reunited in that place. |