|

On the shores of a nameless lake I crouched and shivered

in the wet sage-brush. It was breaking day; the smell of the dawn was in

the air, and a clammy mist enveloped the land, through which, in spots,

individual trees showed as shadows, faintly, if near at hand. Further

than that nothing was visible.

Low, mysterious noises came to my ear, and as the light

waxed stronger these became louder, so as to be distinguishable ; the

leap of a fish; the quacking of a couple of ducks in a reed-bed; the

staccato, nervous tapping of a woodpecker; a distant hollow crash in the

depth of the forest; a slight rustle in the bushes behind me as a weasel

peered out with extended neck, to vanish suddenly, appearing

instantaneously ten feet away almost before his disappearance had been

registered by the eye.

The mist commenced to rise, and a current of air stirred

the poplar leaves to a light fluttering. The ducks became partly

visible, and seen through the vapour they seemed to float on air, and to

be of inordinate size.

I shivered some more.

Under the influence of the slight breeze the fog billowed

slowly back exposing the little sheet of water; the wavering line of the

hills on the far shore appeared and disappeared within its folds, and

the crest of the ridges seemed to float on its surface like long, low

islands. To the East was clear of fog and the streaks of clouds that

hung there, as I watched, turned slowly pink. Not ten feet away, on a

log, a muskrat rubbed himself dry with vigorous strokes, and as he

scrubbed mightily I could hear his little gusts of breath in the thin

air. A flock of whistlers volleyed overhead with bullet velocity,

circled the pond and lit on the water with a slithering splash; a

kingfisher dived like an emerald streak at the rise of a speckled trout,

and, missing his stroke, flew with a chattering laugh to a dry limb. And

at the discordant sound came the first notes of the plaintive song of

the Canada bird, a haunting melody that ceases in full flight, the

remainder of the song tantalisingly left unsung as though the singer had

become suddenly weary: a prelude in minor cadence. And from all around,

and across the pond, these broken melodies burst out in answering

lament, while the burden of song was taken up by one after another

trilling voice. There poured out the rippling lilt of the American

robin, suggestive of the clear purling of running water; the three deep

golden notes of some unknown songster, the first three chords of an

obbligato plucked from the strings of a bass viol. Others, now

indistinguishable for very volume, joined in as the slowly rising sun

rolled up the curtain of the mist on the grand overture conducted by the

Master Musician, that is the coming of day, in the unspoiled reaches of

the northern wilds.

I drew the blanket-case off my rifle and pumped a shell

into the .breech. I was there with a purpose: for the time was that of

the spring hunt, and this was a beaver-pond. Two deer appeared in the

reeds in a little bay, necks craned, nostrils working as they essayed

with delicate senses to detect the flaw in the perfectly balanced

structure of the surroundings which I constituted. I did not need them;

and moreover, did they take flight with hoarse whistles and noisy

leapings all living creatures within earshot would be immediately

absorbed by the landscape, and my hunt ended. But I am an old hand at

the game, and, having chosen a position with that end in view, was not

to be seen, heard, or smelled.

Yet the scene around me had its influence, and a guilty

feeling possessed me as I realized that of all present in that place of

peace and clean content, I was the only profane thing, an ogre lurking

to destroy. The half-grown ferns and evergreen sedge grasses through

which the early breeze whispered, would, if I had my way, soon be

smeared with the blood of some animal, who was viewing, perhaps with

feelings akin to my own, the dawning of another day; to be his last.

Strange thoughts, maybe, coming from a trapper, one whose trade it is to

kill; but be it known to you that he who lives much alone within the

portals of the temple of Nature learns to think, and deeply, of things

which seldom come within the scope of ordinary life. Much killing brings

in time, no longer triumph, but a revulsion of feeling.

I have seen old hunters, with their hair silvered by the

passage of many winters, who, on killing a deer would stroke the dead

muzzle with every appearance of regret. Indians frequently address an

animal they are about to kill in terms of apology for the act. However,

be that as it may, with the passing of the mist from the face of the

mountains, I saw a large beaver swimming a short distance away. This was

my game; gone were my scruples, and my humane ideas fled like leaves

before the wind. Giving the searching call of these animals, I cocked my

rifle and waited.

At the call he stopped, raising himself in the water to

sniff; and on the summons being repeated he swam directly towards me,

into the very jaws of destruction. At about fifteen feet I had a good

view of him as he slowed down, trying to catch some indication of a

possible companion, and the beautiful dark fur apprised me of a hide

that would well repay my early morning sortie. The beaver regarded me

steadily, again raising himself to catch an expected scent, and not

getting it he turned lazily to swim away. He was at my mercy, and I had

his head snugly set between the forks of my rear sight, when my heart

contracted at the thought of taking life on such a morning. The creature

was happy, glad to be in God’s good sunlight, free after a winter of

darkness to breathe the pure air of the dawn. He had the right to live

here, even as I had, yea, even a greater claim, for he was there before

me.'

I conquered my momentary weakness; for, after all, a

light pressure on the trigger, a crashing impact, would save him many

days of useless labour. Yet I hesitated, and as I finally laid my rifle

down, he sank without a ripple, out of sight. And I became suddenly

conscious of the paeans of praise and triumph of the feathered choir

about me, temporarily unheard in my lust to kill; and it seemed as

though all Nature sang in benediction of an act which had kept inviolate

a sanctuary, and saved a perfect hour from desecration.

I went home to my cabin and ate my breakfast .with

greater satisfaction than the most expertly accomplished kill had ever

given me; and, call it what you will, weakness, vacillation, or the

first glimmerings of conscience in a life hitherto devoted to the

shedding of blood, since the later experiences I have had with these

animals I look back on the incident with no regret.

At one time beaver were to the north what gold was to the

west. In the early mining camps gold was the only medium of exchange;

and from time immemorial at the northern trading posts a beaver hide was

the only currency which remained always at par, and by its unchanging

value, all other furs were judged. It took so many other hides to equal

a beaver skin; and its value was one dollar. Counters were threaded on a

string, each worth a dollar, and called “beaver,” and as the hunter sold

his fur its equivalent in “beaver” counters was pushed along the string.

No money changed hands. So many discs were replaced in settlement of the

hunting-debt, and as the trapper bought his provisions the remaining

“beaver” were run back down again, one by one, a dollar at a time, until

they were all back where they belonged, and the trade completed.

They usually went back down the string a good deal faster

than they came up, and the story is told of the hunter with two bales of

fur who thus paid his debt, spoke twice, and owed a hundred dollars.

Although pelts were cheap provisions were not. I have spoken with men,

not such very old men either, who traded marten, now selling as high as

forty dollars, at the rate of four to a beaver, or twenty-five cents

each.

A hunter must have had to bring in a stupendous amount of

fur to buy even the barest necessities, when we consider the prices that

even to-day obtain at many of the distant posts; a twenty-five pound bag

of flour, $5.00; salt pork, $1.00 a pound; tea, $3.00 a pound; candles,

25 c. each; sugar, 50 c. a pound; 5 lb. pail of lard, $4.5:0; a pair of

trousers, $25.00; and so on. The oft-told tale of piling beaver hides to

the height of the muzzle of a gun in order to purchase the weapon,

although frequently denied, is perfectly true. Many old Indians living

to-day possess guns they bought that way. It is not so generally known

that some unscrupulous traders increased the price by lengthening the

barrels, necessitating the cutting off of a length with a file before

the weapon could be used.

Although beaver do not exist to-day in sufficient

quantities to constitute a hunt, up till ten years ago they were the

chief means of subsistence of an army of white hunters, and thousands of

Indians. Since their practical extermination the Northern Ojibways are

in want, and many of the bands have had to be rationed by the Government

to prevent their actual starvation.

The first, and for over a hundred years, the only

business in which Canada was engaged was the fur trade, of which the

beaver was the mainstay; and its history affords one of the most

romantic phases in the development of the North American Continent.

The specimens of beaver pelts exhibited to Charles of

England influenced him to grant the famous Hudson Bay Company’s Charter,

apportioning to them probably the largest land grant ever awarded any

one concern. Attracted by the rich spoils of the trade, other companies

sprang up. Jealousies ensued, and pitched battles between the trappers

of rival factions were a common occurrence. Men fought, murdered,

starved and froze to death, took perilous trips into unknown

wildernesses, and braved the horrors of Indian warfare, lured on by the

rich returns of the beaver trade. Men_ foreswore one another, cheated,

murdered, robbed, and lied to gain possession of bales of these pelts,

which could not have been more ardently fought for had each hair on them

been composed of gold.

The Indians, meanwhile, incensed at the wholesale

slaughter of their sacred animal, inflamed by the sight of large bands

of men fighting for something that belonged to none of them, took pay

from either side, and swooped down on outgoing caravans, annihilating

them utterly, and burning peltries valued at hundreds of thousands of

dollars. Often, glad of a chance to strike a blow at the beaver man, the

common enemy, they showed a proper regard for symmetry by also

destroying the other party that had hired them, thus restoring the

balance of Nature. Ghastly torturing and other diabolical atrocities,

incident to the massacre of trappers in their winter camps, discouraged

hunting, and crippled the trade for a period; but with the entire

extinction of the buffalo the Indian himself was obliged to turn and

help destroy his ancient friends in order to live. Betrayed by their

protectors the beaver did not long survive, and soon they were no more

seen in the land wherein they had dwelt so long.

Profiting by this lesson, forty years later, most of the

Provinces on the Canadian side of the line declared a closed season on

beaver, of indefinite duration. Thus protected they gradually increased

until at the outbreak of the World War they were as numerous in the

Eastern Provinces as they ever had been in the West. I am not an old

man, but I have seen the day when the forest streams and lakes of

Northern Ontario and Quebec were peopled by millions of these animals.

Every creek and pond had its colony of the Beaver People. And then once

again, and for the last time, this harassed and devoted animal was

subjected to a persecution that it is hard to credit could be possible

in these enlightened days of preservation and conservation. The beaver

season was thrown open and the hunt was on.

Men, who could well have made their living in

other 146 ways, quit their regular occupations and took the trail. It

was the story of the buffalo over again. In this case instead of an

expensive outfit of horses and waggons, only a cheap licence, a few

traps, some provisions and a canoe were needed, opening up widely the

field to all and sundry.

The woods were full of trappers. Their snowshoe trails

formed a network of destruction over all the face of the wilderness,

into the farthest recesses of the north. Trails were broken out to

civilization, packed hard as a rock by long strings of toboggans and

sleighs drawn by wolf-dogs, and loaded with skins; trails over which

passed thousands and thousands of beaver hides on their way to the

market. Beaver houses were dynamited by those whose intelligence could

not grasp the niceties of beaver trapping, or who had not the hardihood

to stand the immersion of bare arms in ice-water during zero weather;

for the setting of beaver traps in mid-winter is no occupation for one

with tender hands or a taste for tea-fights. Dams were broken after the

freeze-up, and sometimes the entire defences, feed house, and dam were

destroyed, and those beaver not captured froze to death or starved in

their ruined works, whilst all around was death, and ruin, and

destruction.

Relentless spring hunters killed the mother beavers,

allowing the little ones to starve, which, apart from the brutality of

the act, destroyed all chances of replenishment. Unskilful methods

allowed undrowned beaver to twist out of traps, leaving in the jaws some

shattered bone and a length of sinew, condemning the maimed creatures to

do all their work with one or both front feet cut off; equivalent in its

effect to cutting off the hands of a man.

I once saw a beaver with both front feet and one hind

foot cut off in this way. He had been doing his pitiful best to collect

materials for his building. He was quite far from the water and unable

to escape me, and although it was late summer and the hide of no value,

I put him out of misery with a well-placed bullet.

Clean trapping became a thing of the past, and

unsportsmanlike methods were used such as removing the raft of feed so

that the beaver must take bait or starve; and the spring pole, a

contrivance which jerks the unfortunate animal into the air, to hang for

hours by one foot just clear of the water, to die in prolonged agony

from thirst. To inflict such torture on this almost human animal is a

revolting crime which few regular white hunters and no Indian will stoop

to.

I remember once, on stopping to make camp, hearing a

sound like the moaning of a child a few yards away, and I rushed to the

spot with all possible speed, knowing bear traps to be out in the

district. I found a beaver suspended in this manner, jammed into the

crotch of a limb, held there by the spring pole, and moaning feebly. I

took it down, and found it to be a female heavy with young, and in a

dying condition; my attempts at resuscitation were without avail, and

shortly after three lives passed into the discard.

The Government of Ontario imposed a limit on the number

to be killed, and attempted, futilely, to enforce it; but means were

found to evade this ruling, and men whose allowance called for ten hides

came out with a hundred. There is some sorcery in a beaver hide akin to

that which a nugget of gold is credited with possessing, and the

atmosphere of the trade in these skins is permeated with all the romance

and the evil, the rapacity and adventurous glamour, attendant on a

gold-rush. Other fur, more easily caught, more valuable perhaps, may

increase beyond all bounds, and attract no attention save that of the

professional trapper, but at the word “ beaver,” every man on the

frontier springs to attention, every ear is cocked. The lifting of the

embargo in Ontario precipitated a rush, which whilst not so

concentrated, was very little, if any, less than that of ’98 to the

Yukon. Fleets, flotillas, and brigades of canoes were strung out over

the surface of the lakes in a region of many thousand square miles,

dropping off individually here and there into chosen territories, and

emerging with spectacular hunts unknown in earlier days. The plots and

counter-plots, the intrigues and evasions connected with the tricks of

the trade, resembled the diplomatic ramifications of a nation at war.

History repeated itself. Fatal quarrels over hunting

grounds were not unknown, and men otherwise honest, bitten by the bug of

greed and the prospect of easy money, stooped to unheard-of acts of

depravity for the sake of a few hides.

Meanwhile the trappers reaped a harvest, but not for

long. Beaver in whole sections disappeared and eyes were turned on the

Indian countries. The red men, as before, looked on, but this time with

alarm. Unable any longer to fight for this animal, which, whilst no

longer sacred was their very means of existence, they were compelled to

join in the destruction, and ruin their own hunting grounds before

others got ahead of them and took everything. For ten years the

slaughter went on, and then beaver became scarce.

The part-time hunter, out for a quick fortune, left the

woods full of poison baits, and polluted with piles of carcases, and

returned to his regular occupation. The Indian hunting grounds and those

of the regular white trappers had been invaded and depleted of game. The

immense number of dog-teams in use necessitated the killing of large

numbers of moose for feed, and they also began to be scarce.

Professional hunters, both red and white, even if only to protect their

own interests, take only a certain proportion of the fur, and trapping

grounds are maintained in perpetuity. The invaders had taken everything.

To-day, in the greater part of the vast wilderness of

Northern Canada, beaver are almost extinct; they are fast going the way

of the buffalo. But their houses, their dams, and all their works will

long remain as a reproach and a heavy indictment against the shameful

waste perpetrated by man, in his exploitation of the wild lands and the

dwellers therein. Few people know, or perhaps care, how close we are to

losing most of the links with the pioneer days of old; the beaver is one

of the few remaining reminders of that past Canadian history of which we

are justly proud, and he is entitled to some small niche in the hall of

fame. He has earned the right to our protection whilst we yet have the

power to exercise it, and if we fail him it will not be long before he

is beyond our jurisdiction for all time.

The system that has depleted the fur resources of Canada

to a point almost of annihilation, is uncontrolled competitive hunting

and trapping by transient white trappers. .

The carefully-farmed hunting territories of the Indians

and the resident white trappers (the latter being greatly in the

minority, and having in most cases a proprietary interest in the

preservation of fur and game, playing the game much as the Indian played

it) were, from 1915 on, invaded by hordes of get-rich-quick vandals who,

caring for nothing much but the immediate profits, swept like the

scourge they were across the face of northern Canada.

These men were in no way professional hunters; their

places were in the ranks of other industries, where they should have

stayed. The Indian and the dyed-in-the-wool genuine woodsmen, unsuited

by a long life under wilderness conditions to another occupation, and

unable to make such a revolutionary change in their manner of living,

now find themselves without the means of subsistence.

Misinformed and apparently not greatly interested

provincial governments aided and abetted this destructive and

unwarranted encroachment on the rights of their native populations who

were dependent entirely on the proceeds of the chase, by gathering a

rich if temporary harvest in licences, royalties, etc. A few futile laws

were passed, of which the main incentive of enforcement often seemed to

be the collection of fines rather than prevention. Money alone can never

adequately pay the people of Canada for the loss of their wild life,

from either the commercial, or recreational, or the sentimental point of

view.

We read of the man who opened up the goose to get all the

golden eggs at once, and the resultant depression in the golden-egg

market that followed. The two cases are similar.

We blame the United States for their short-sighted policy

in permitting the slaughter of the buffalo as a means of solving the

Indian problem of that time, yet we have allowed, for a paltry

consideration in dollars and cents, and greatly owing to our criminal

negligence in acquainting ourselves with the self-evident facts of the

case, the almost entire destruction of our once numerous fur-bearing and

game animals. Nor did this policy settle any Indian problem, there being

none at the time, but it created one that is daily becoming more

serious. The white man’s burden will soon be no idle dream, and will

have to be assumed with what cheerful resignation you can muster.

We must not fail to remember that we are still our

brother’s keeper, and having carelessly allowed this same brother to be

robbed of his rights and very means of existence (solemnly agreed by

treaty to be inalienable and. perpetual, whereby he was a

self-supporting producer, a contributor to the wealth of the country and

an unofficial game warden and conservationist whose knowledge of wild

life would have been invaluable) we must now support him. And this will

complete his downfall by the degrading “dole” system.

At a meeting I attended lately, it was stated by a

competent authority that there were more trappers in the woods during

this last two years than ever before. The fact that they paid for their

licences does not in any way compensate either the natives or the

country at large for the loss in wild life consequent on this wholesale

slaughter.

The only remedy would seem to be the removal from the

woods of all white trappers except those who could prove that they had

no alternative occupation, had followed trapping for a livelihood

previous to 1914 (thus eliminating the draft evaders and others who hid

in the woods during the war) and returned men of the voluntary

enlistment class. It is not perhaps generally known that the draft

evaders in some sections constitute the majority of the more destructive

element in the woods to-day. Forced to earn a livelihood by some means

in their seclusion, and fur being high at the time, they learned to trap

in a kind of way. They constitute a grave menace to our fur and game

resources, as their unskilful methods make necessary wholesale

destruction on all sides in order to obtain a percentage of the fur,

leaving in their path a shambles of unfound bodies, many of them

poisoned, or crippled animals, which, unable to cope with the severe

conditions thus imposed on them, eventually die in misery and

starvation.

Regulations should be drawn up with due regard for

conditions governing the various districts, these to be ascertained from

genuine woodsmen and the more prominent and responsible men of native

communities. Suggestions from such sources would have obviated a good

deal of faulty legislation. Those entrusted with the making of our game

laws seem never to become acquainted with the true facts until it is

almost too late, following the progress of affairs about a lap behind.

Regulations, once made, should be rigorously enforced,

and penalties should include fines and imprisonment, as many illegal

trappers put by the amount of a possible fine as a part of their

ordinary expenses.

There is another point of view to be considered. If the

depletion of our game animals goes on much longer at the present rate,

specimens of wild life will soon be seen only in zoos and menageries.

How much more elevating and instructive is it to get a

glimpse—however fleeting—of an animal in its native haunts than the

lengthy contemplation of poor melancholy captives eking out a thwarted

existence under unnatural conditions? Fur farms may perpetuate the fur

industry eventually unless the ruinous policy of selling, for large and

immediate profits, breeding animals to foreign markets is continued. But

these semi-domesticated denatured specimens will never represent to the

true lover of Nature the wild beauty and freedom of the dwellers in the

Silent Places, nor will they ever repopulate the dreary empty wastes

that will be all that are left to us when the remaining Little Brethren

have been immolated on the altars of Greed and Ignorance, and the

priceless heritage of both the Indian and the white man destroyed for

all time.

In wanderings during the last five years, extending

between, and including, the Districts of Algoma in the Province of

Ontario and Misstassini in the Province of Quebec, and covering an

itinerary of perhaps two thousand miles, I have seen not over a dozen

signs of beaver. I was so struck by this evidence of the practical

extinction of our national animal, that my journey, originally

undertaken with the intention of finding a hunting ground, became more

of a crusade, conducted with the object of discovering a small colony of

beaver not claimed by some other hunter, the motive being no longer to

trap, but to preserve them.

I have been fortunate enough to discover two small

families. With them, and a few hand-raised specimens in my possession, I

am attempting the somewhat hopeless task of repopulating a district

otherwise denuded of game. It is a little saddening to see on every hand

the deserted works, the broken dams, and the empty houses, monuments to

the thwarted industry of an animal which played such an important part

in the history of the Dominion.

Did the public have by any chance the opportunity of

studying this little beast who seems almost able to think, possesses a

power of speech in which little but the articulation of words is

lacking, and a capacity for suffering possible only to a high grade of

intelligence, popular opinion would demand the declaration of a close

season of indefinite duration over the whole Dominion.

Did the Provinces collaborate on any such scheme, there

would be no sale for beaver skins, and the only source of supply being

thus closed, poaching would be profitless. Even from a materialistic

point of view this would be of great benefit, as after a long, it is to

be feared a very long, period a carefully regulated beaver hunt could be

arranged that would be a source of revenue of some account.

It is generally conceded that the beaver was by far the

most interesting and intelligent of all the creatures that at one time

abounded in the vast wilderness of forest, plain and mountain that was

Canada before the coming of the white man.

Although in the north they are now reduced to a few

individuals and small families scattered thinly in certain inaccessible

districts, there has been established for many years, a game reserve of

about three thousand square miles, where these and all other animals

indigenous to the region are as numerous as they were fifty years ago. I

refer to the Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario. This game sanctuary

is guarded in the strictest manner by a very competent staff of Rangers,

and it is a saying in the region that it would be easier to get away

with murder than to escape the consequences of killing a beaver in their

patrol area.

This little worker of the wild has been much honoured. He

ranks with the maple leaf as representative of the Dominion, and has won

a place as one of Canada’s national emblems, by the example he gives of

industry, adaptability, and dogged perseverance; attributes well worthy

of emulation by those who undertake to wrest a living from the untamed

soil of a new country. He is the Imperialist . of the animal world. He

maintains a home and hearth, and from it he sends out every year a pair

of emigrants who search far and wide for new fields to conquer; who

explore, discover, occupy, and improve, to the benefit of all concerned.

The Indian, who lived by the killing of animals, held his

hand when it came to the beaver. Bloody wars were waged on his behalf by

his red-skinned protectors, until the improvements of civilization

raised economic difficulties only to be met by the sale of beaver skins,

with starvation as the alternative. _ _

The red men considered them as themselves and dignified

their Little Talking Brothers with the name of The Beaver People, and

even in these degenerate days of traders, whiskey, and lost tradition,

there are yet old men *54

The beaver arrives at the top of the house, with his

load, still erect. He places his armful of mud, packing it into the gap

with his hands, a?id forcing the stick into a crevice by the same means.

The tail is never used for this or any other purpose save as a support

in walking. This beaver house is 22 ft. long, 18 ft. wide and 8 ft.

high. Built by two beavers in less than two months. amongst the nations

who will not sit to a table where beaver meat is served, while those who

now eat him and sell his hide will allow no dog to eat his bones, and

the remains, feet, tail, bones and entrails, are carefully committed to

the element from which they came, the water.

It would seem that by evolution or some other process,

these creatures have developed a degree of mental ability superior to

that of any other living animal, with the possible exception of the

elephant.

Most animals blindly follow an instinct and a set of

habits, and react without mental effort to certain inhibitions and

desires. In the case of the beaver, these purely animal attributes are

supplemented by a sagacity which so resembles the workings of the human

mind that it is quite generally believed, by those who know most about

them, that they are endowed to a certain extent with reasoning powers.

The fact that they build dams and houses, and collect feed is sometimes

quoted as evidence of this; but muskrats also erect cabins and store

food in much the same manner. Yet where do you find any other creature

but man who can fall a tree in a desired direction, selecting only those

which can conveniently be brought to the ground? For rarely do we find

trees lodged or hung up by full-grown beaver; the smaller ones are

responsible for most of the lodged trees. Instinct causes them to build

their dams in the form of an arc, but by what means do they gain the

knowledge that causes them to arrange that curve in a concave or a

convex formation, according to the water-pressure?

Some tame beaver objected strongly to the window in my

winter camp, and were everlastingly endeavouring to push up to it

articles of all kinds, evidently thinking it was an opening, which it is

their nature to close up. That was to be expected. But they overstepped

the bounds of natural impulse, and entered the realm of calculation,

when they dragged firewood over, and piled it under the window until

they had reached its level, and on this improvised scaffold they

eventually accomplished their purpose, completely covering the window

with piled-up bedding. Whenever the door was open they tried every means

of barricading the opening, but found they could never get the aperture

filled. One day I returned with a pail of water in each hand to find the

door closed, having to set down my pails to open it. I went in, and my

curiosity aroused, watched the performance. As soon as I was clear, one

of the beaver started to push on some sacking he had collected at the

foot of the door, and slowly but surely closed it. And this he often did

from then on. Instinct? Maybe.

Their general system of working is similar in most cases,

and the methods used are the same. However, in the bush no two places

are alike, and it requires no little ingenuity on the part of a man to

adapt himself to the varying circumstances, yet the beaver can adjust

himself to a multiplicity of different conditions, and is able to

overcome all the difficulties arising, meeting his problems much in the

way a man would.

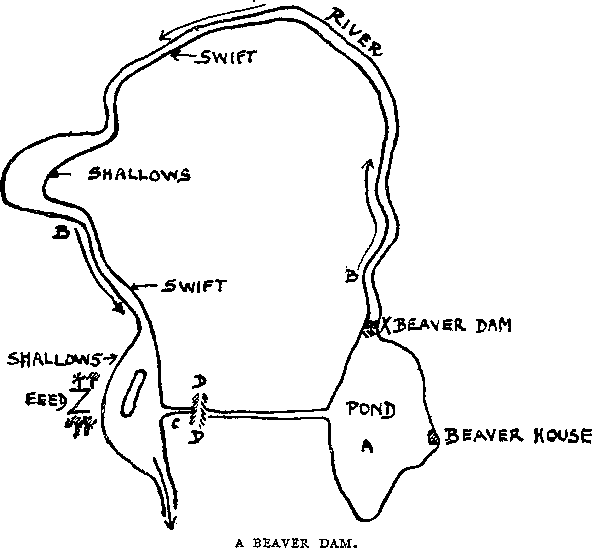

In the accompanying sketch will be seen a lake A,

representing a pond well-known to me on which there was a beaver family.

There was much feed at the place marked Z on the further bank of the

river B,but none on the lake, which had been very shallow, but was

dammed at X. Between the spot on the river marked Z and the lake was a

distance of two hundred yards. The problem was to get the feed across to

the pond. The river route was too far, and to draw it such a distance in

a country bristling with dangers was not to be considered, so the beaver

dug a canal towards the river. Now this stream had run swiftly two miles

or more before it reached the point Z, therefore, naturally at that

place would be much lower than the level of the lake. On the completion

of the canal C the lake would consequently be drained. This the beaver

were well aware of, and to avoid this contingency, the channel was dug

as far as D, discontinued for a few yards, and continued on to the

river, leaving a wall, which being further heightened, prevented the

escape of their precious water.

Thus they could float their timber in ease the full

dis-156 tance, with the exception of one short portage. A problem not

easily solved.

Their strength is phenomenal and they can draw a stick

which, in proportion, a man could not shift with his hands; and to move

it sideways they will go to each extremity alternately, poise the end

over their head and throw it an appreciable distance. I have seen two

small beaver struggling down a runway with a poplar log, heaviest of

soft woods, of such a size that only the top of their backs and heads

were visible above it.

Shooting them when they are so engaged, a common

practice, somehow seems to me in these latter days, like firing from

ambush on children at play, or shooting poor harmless labourers at work

in the fields.

The beaver is a home-loving beast and will travel far

overland, around the shores of lakes and up streams, searching for a

suitable place to build. Once settled where there is enough feed, and

good opportunities to construct a dam, a family is liable to stay in

that immediate district for many years. The young, at the age of two

years, leave home, and separating, pick each a mate from another family,

build themselves a house and dam, and settle down to housekeeping;

staying together for life, a period of perhaps fifteen years. At the end

of the third year they attain full growth, being then three feet and a

half long with the tail, and weighing about thirty-five pounds. In the

spring the mother has her young, the male making a separate house for

them and keeping the dam in repair. The last year’s kittens leave the

pond, going always downstream, and wander around all summer, returning

about August to assist in the work of getting ready for the winter. The

first part of these preparations is to build a dam, low to begin with,

and being made higher as needed. The main object of this structure is to

give a good depth of water, in which feed may be kept all winter without

freezing, and heavy green sticks are often piled on top of the raft of

supplies, which is generally attached to the house, in order to sink it

as much as possible. Also by this means the water is flooded back into

the timber they intend to fall, enabling them to work close to the water

and facilitating escape from danger.

Much has been said concerning the timber they are

supposed to spoil in this way, but the shores of a lake are hardly ever

low enough to allow any more than the first narrow fringe of trees close

to the water to be drowned, and that is generally of little value

commercially.

The immense amount of work that is put into a dam must be

seen to be realized. Some of these are eight feet high, a hundred yards

long, and six feet through at the base, tapering up to a scant foot at

the water level. Pits are dug near the ends from which are carried the

materials to prevent seepage, and a judicious admixture of large stones

adds the necessary stiffening at the water-lines. Canals are channelled

out, trees felled near them, neatly limbed, cut up, and all but the

heavier portions drawn to the water and floated away. The heightened

water facilitates this operation, and besides thus fulfilling his own

purpose, the beaver is performing a service for man that, too late, is

now being recognized. .

Many a useful short-cut on a circuitous canoe route,

effecting a saving of hours, and even days, a matter of the greatest

importance in the proper policing of the valuable forests against fire,

has become impracticable since the beaver were removed, as the dams fell

out of repair, and streams became too shallow for navigation by canoes.

The house alone is a monument of concentrated effort. The

entrance is under water, and on a foundation raised to the water level,

and heightened as the water rises, sticks of every kind are stacked

criss-cross in a dome shaped pile some eight feet high and from ten to

twenty-five feet in width at the base. These materials are placed

without regard to interior accommodation, the interstices filled with

soil, and the centre is cut out from the inside, all hands chewing away

at the interlaced sticks until there is room enough in the interior for

a space around the waterhole for a feeding place, and for a platform

near the walls for sleeping quarters. The beds are made of long

shavings, thin as paper, which they tear off sticks; each beaver has his

bed and keeps his place.

Pieces of feed are cut off the raft outside under the

ice, and peeled in the house, the discarded sticks being carried out

through a branch in the main entrance, as are the beds on becoming too

soggy. Should the water sink below the level of the feeding place the

loss is at once detected, and the dam inspected and repaired. Thus they

are easy to catch by making a small break in the dam and setting a trap

in the aperture. On discovering the break they will immediately set to

work to repair it without loss of time, and get into the trap. When it

closes on them they jump at once into deep water and, a large stone

having been attached to the trap, they stay there and drown, taking

about twenty minutes to die; a poor reward for a lifetime of useful

industry.

Late in the Fall the house is well plastered with mud,

and it is by observing the time of this operation that it is possible to

forecast the near approach of the freeze-up.

And it is the contemplation of this diligence and

perseverance, this courageous surmounting of all difficulties at no

matter what cost in labour, that has, with other considerations, earned

the beaver, as far as I am concerned, immunity for all time. I cannot

see that my vaunted superiority as a man entitles me to disregard the

lesson that he teaches, and profiting thereby, I do not feel that I have

any longer the right to destroy the worker or his works performed with

such devotion.

Many years have I builded, and hewed, and banked, and

laboriously carried in my supplies in readiness for the winter, and all

around me the Beaver People were doing the same thing by much the same

methods, little knowing that their work was all for nought, and that

they were doomed beforehand never to enjoy the comfort they well earned

with such slavish labour.

I recollect how once I sat eating a lunch at an open fire

on the shores of a beautiful little mountain lake, and beside me, in the

sunlight, lay the body of a fine big beaver I had just caught. I well

remember, too, the feeling of regret that possessed me for the first

time, as I watched the wind playing in the dead beaver’s hair, as it had

done when he had been happy, sunning himself on the shores of his pond,

so soon to become a dirty swamp, now that he was taken.

In spite of his clever devices for protection, the

beaver, by the very nature of his work signs his own death warrant. The

evidences of his wisdom and industry, for which he is so lauded, have

been after all, only sign-posts on the road to extinction. Everywhere

his bright new stumps show up. His graded trails, where they enter the

water, form ideal sets for traps and he can be laid in wait for and shot

in his canals. Even with six feet of snow blanketing the winter forest,

it can be easily discovered whether a beaver-house is occupied or not,

by digging some snow off the top of the house and exposing the large

hollow space 160

melted by the exhalations from within. The store of feed

so carefully put by, may prove his undoing, and he be caught near it by

a skilfully placed trap. Surely he merits a better fate than this, that

he should drown miserably three feet from his companions and his empty

bed, whilst his body lies there until claimed by the hunter, later to

pass, on the toboggan on its way to the hungry maw of the city, the home

he worked so hard to build, the quiet and peace of the little pond that

knew him and that he loved so well.

This then is the tale of the Beaver People, a tale that

is almost told. Soon all that will remain of this once numerous clan of

little brethren of the waste places will be their representative in his

place of honour on the flag of Canada. After all an empty mockery, for,

although held up to symbolize the Spirit of Industry of a people, that

same people has allowed him to be done to death on every hand, and by

every means. Once a priceless exhibit displayed for a king’s approval,

the object of the devotion of an entire race, and wielding the balance

of power over a large continent, he is now a fugitive. Unable to follow

his wonted occupation, lest his work show his presence, scarcely he

dares to eat except in secrecy, lest he bring retribution swift and

terrible for a careless move. Lurking in holes and corners, in muddy

ponds and deep unpenetrable swamps, he dodges the traps, snares, spring

poles, nets, and every imaginable device set to encompass his

destruction, to wipe him off the face of the earth.

Playful and good-natured, persevering and patient, the

scattered remnants of the beaver colonies carry on, futilely working out

their destiny until such time as they too will fall a victim to the

greed of man. And so they will pass from sight as if they had never

been, leaving a gap in the cycle of wilderness life that cannot be

filled. They will vanish into the past out of which they came, beyond

the long-forgotten days, from whence, if we let them go, they can never

be recalled. |