|

Banff—Its Location— The

Village— Tourists—Hotels— Topography of the Region—Rundle and Cascade

Mountains — The Devil's Lake—Sir George Simpson s Journey to this

Region—Peechee the Indian Guide— An Indian Legend—The Missionary

Rundle—Dr. Hectoi—The Climate of Banff—A Summer Snow-Storm—The Mountains

in Winter.

THE principal resort of

tourists and sportsmen in the Rocky Mountains of Canada is Banff. The

location of the town or village of Banff might be briefly described as

being just within the eastern-most range of the Rocky Mountains, about

one hundred and fifty miles north of the International boundary, or

where the Canadian Pacific Railway begins to pierce the complex system

of mountains which continue from this point westward to the Pacific

coast.

Banff is likewise the

central or focal point of the Canadian National Park. There is so much

of scenic interest and natural beauty in the surrounding mountains and

valleys, that an area of some two hundred and sixty square miles has

been reserved in this region by the government and laid out with fine

roads and bridle-paths to points of special interest. Order is enforced

by a body of men known as the Northwest Mounted Police, a detachment of

which is stationed at Banff. This organization has been wonderfully

effective for many years past in preserving the authority of the laws

throughout the vast extent of northwestern Canada by means of a number

of men that seems altogether insufficient for that purpose.

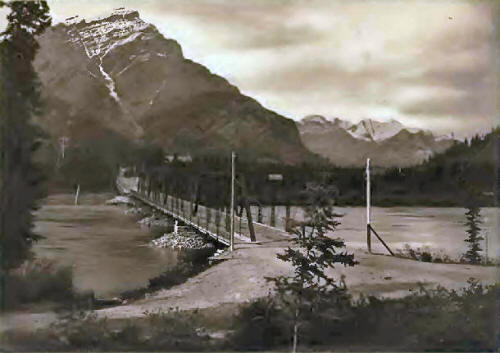

The small and scattered

village of Banff occupies a flat plain near the Bow River. This large

stream, the south branch of the Saskatchewan, one of the greatest rivers

of North America, is at this point not only deep^ and swift but fully

one hundred yards in width. A fine iron bridge spans the river and leads

to the various hotels all of which are south of the village. The

permanent population numbers some half thousand, while the various

stores, dwellings, and churches have a general air of neatness and by

their new appearance suggest the fact that the history of Banff extends

back only one decade.

During the summer

season, the permanent population of Banff is sometimes nearly doubled by

a great invasion of tourists and travellers from far distant regions.

Overland tourists from India, China, Ceylon, and England, the various

countries of Europe and the Dominion of Canada, but chiefly from the

United States, form the greater part of this cosmopolitan assemblage, in

which, however, almost every part of the globe is occasionally

represented. Some are bent on sport with rod or gun; others on

mountaineering or camping expeditions, but the great majority are en

route to distant countries and make Banff a stopping-place for a short

period.

Arrived at Banff, the

traveller is confronted by a line of hack drivers and hotel employes

shouting in loud voices the names and praises of their various hotels.

Such sights and sounds are a blessed relief to the tourist, who for

several days has witnessed nothing but the boundless plains and scanty

population of northwestern Canada. The chorus of rival voices seems

almost a welcome back to civilization, and reminds one in a mild degree

of some railroad station in a great metropolis. On the contrary, the new

arrival finds, as he is whirled rapidly toward his hotel in the coach,

that he is in a mere country village surrounded on all sides by high

mountains, with here and there patches of perpetual snow near their

lofty summits.

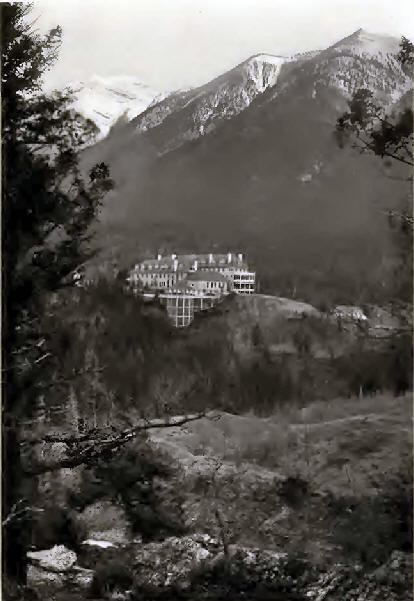

Though the surrounding

region, the adjacent mountains, and valleys represent nature in a wild

and almost primitive state, one may remain at Banff attended by all the

comforts of civilization. The several hotels occupy more or less

scattered points in the valley south from the village. The one built and

managed by the railroad stands apart from the village on an eminence

overlooking the Bow River. It is a magnificent structure capable of

accommodating a large number of guests. From the verandas and porches

one may obtain a fine panoramic view of the surrounding mountains, and

on the side towards the river the view combines water, forest, and

mountain scenery in a most pleasing manner. The Bow River, some three

hundred feet below, comes in from the left and dashes in a snowy cascade

through a rocky gorge, then, sweeping away towards the east, is joined

by the Spray River, a mad mountain torrent deep and swift, but clear as

crystal, and with cold water of that deep blue color indicating its

mountain origin. The wonderful rapidity with which these mountain

streams flow is a source of astonishment and wonder to those familiar

only with the sluggish rivers of lowland regions. Standing on the little

iron bridge which carries the road across the stream and looking down on

the water, I have often imagined I was at the stern of an ocean

greyhound, so rapidly does each ripple or inequality sweep under and

away from the eye. Though the water is less than a yard in depth, the

current moves under the bridge at the rate of from nine to ten miles an

hour.

The best point from

which to get a good general idea of the topography of Banff and its

surroundings is from the summit of a little hill known as Tunnel

Mountain. It is centrally located in the wide valley of the Bow, above

which it rises exactly iooo feet, an altitude great enough to make it

appear a high mountain were it not dwarfed by its mighty neighbors. The

view from the summit is not of exceeding grandeur, but is well worth the

labor of the climb, especially as a good path, with occasional seats for

the weary, makes the walk an easy one. The top of the mountain is still

far below the tree line, though the earth is too thin to nourish a rich

forest. The soil was

all carried away in the

Ice Age, for there are abundant proofs that this mountain was once

flooded by a glacier coming down the Bow valley. The bare limestone of

the summit is grooved in great channels pointing straight up the Bow

valley. In some places scratches made by the ice are visible, and there

are many quartz boulders strewed about which have been carried here from

some distant region.

The meandering course

of the Bow River, the village, the hay meadows and grassy swamps, all

form a pretty picture in the flat valley below. The eastern face of

Tunnel Mountain is wellnigh perpendicular. The trail leads along near

the summit and allows thrilling views down the sheer precipice to the

flat valley of the Bow River far below. The trees and prominent objects

of the landscape seem like toys, and the adjacent plains resemble a

colored map. There are no houses or dwellings in view on this side, but

a drove of horses grazing contentedly in a pasture near the river,

awaiting their turn to be sent out into the mountains in the pack train

of some sportsman or mountaineer, gives life and animation to the scene.

On either side are two high mountains, conspicuous by their unusual

outlines and great altitude. The one to the south is Rundle Mountain. It

rises in a great curving slope on its west side, and terminates in a

rugged escarpment with precipitous cliffs to the east, which tower in

wonderful grandeur more than 5000 feet above the flood plains of the Bow

River near its base.

On the opposite side is

Cascade Mountain, which is remarkable in being of almost identical

height, and is in fact just two feet lower, as determined by the

topographical survey. The name of this mountain was given by reason of a

large stream which falls from ledge to ledge down the cliffs of its

eastern face in a beautiful cascade. Both this and Rundle Mountain are

composed of the old Devonian and Carboniferous limestones, the strata of

which are plainly visible. The structure is that of a great arch or

anticline which has been completely overturned, so that the older beds

are above the newer. Several miles towards the east*, the end of Devil’s

Lake may be seen appearing through a notch in the mountains. A fine road

nine miles in length has been made to this lake and is one of the most

popular drives in the vicinity of Banff. The lake is very long and

narrow, about nine miles in length by three fourths of a mile in extreme

breadth. The scenery is grand, but rather desolate, as the bare mountain

walls on either side of the lake are not relieved by forests or abundant

vegetation of any kind. The lake is, however, a great resort for

sportsmen as it abounds in large trout, of which one taken last year

weighed thirty-four pounds. The name of the lake gives illustration of

the tendency among savages and civilized people to dedicate prominent

objects of nature to the infernal regions or the master spirit thereof.

There is no apparent limit to the number of places named after the Devil

and his realm, while the names suggested by more congenial places are

conspicuous by their absence. The original name, Lake Peechee, was given

by Sir George Simpson in honor of his guide.

The scattered threads

of history which relate to this part of the Rocky Mountains are

suggested by these names and indeed this lake has an unusual interest

for this reason. In a region where explorations have been very few and

far between, and where only the vague traditions of warlike events among

the Indians form a great part of the history, each fragment and detail

set forth by the old explorers acquires an increased interest.

Previous to the arrival

of the railroad surveyors, the chief men on whom our attention centres

are Sir George Simpson, Mr. Rundle, and Dr. Hector.

The expedition of Sir

George Simpson possesses much of interest in every way. He claims to

have been the first man to accomplish an overland journey around the

world from east to west. After having traversed the greater part of the

continent of North America, he entered the stupendous gates of the Rocky

Mountains in the autumn of 1841. He travelled with wonderful rapidity,

and was wont to cover from twenty to sixty miles a day, according to the

nature of the country. His outfit consisted of a large band of horses,

about forty-five in number, attended by cooks and packers sufficient for

the needs of this great expedition. Nevertheless the long cavalcade of

animals, when spread out in Indian file along the narrow trails were

difficult to manage, and it not infrequently happened that on reaching

camp several horses proved to be missing, a fact which would necessitate

some of the men returning fifteen or twenty miles in search of them.

Passing to the south of

the Devil’s Head, a remarkable and conspicuous mountain which may be

recognized far out on the plains, Sir George Simpson entered the valley

occupied by the lake. In this part of his journey he was guided by a

half-breed Indian named Peechee, a chief of the Mountain Crees. Peechee

lived with his wife and family on the borders of this lake, and Simpson

named it after him, a name, however, which never gained currency. Dr.

Dawson transferred the name to a high mountain south of the lake, and

substituted the Indian name of Minnewanka, or in English, Devil’s Lake.

The guide Peechee seems

to have possessed much influence among his fellows, and whenever, as was

often the case, the Indians gathered around their camp-fires and

gossiped about their adventures, Peechee was listened to with the

closest attention on the part of all. Nothing more delights the Indians

than to indulge their passion for idle talk when assembled together,

especially when under the soothing and peaceful influence of tobacco,—a

fact that seems strange indeed to those who see them only among

strangers, where they are wont to be remarkably silent.

A circumstance of

Indian history connected with the east end of the lake is mentioned by

Sir George Simpson, and admirably illustrates the nature of savage

warfare. A Cree and his wife, a short time previously, had been tracked

and pursued by five Indians of a hostile tribe into the mountains to a

point near the lake. At length they were espied and attacked by their

pursuers. Terrified by the fear of almost certain death, the Cree

advised his wife to submit without defending herself. She, however, was

possessed of a more courageous spirit, and replied that as they were

young and had but one life to lose they had better put forth every

effort in self-defence. Accordingly she raised her rifle and brought

down the foremost warrior with a well aimed shot. Her husband was now

impelled by desperation and shame to join the contest, and mortally

wounded two of the advancing foe with arrows. There were now but two on

each side. The fourth warrior had, however, by this time reached the

Cree’s wife and with upraised tomahawk was on the point of cleaving her

head, when his foot caught in some inequality of the ground and he fell

prostrate. With lightning stroke the undaunted woman buried her dagger

in his side. Dismayed by this unexpected slaughter of his companions,

the fifth Indian took to flight after wounding the Cree in his arm.

Rundle Mountain, which

has been already mentioned and which forms one of the most striking

mountains in the vicinity of Banff, is named after a Wesleyan missionary

who for many years carried on his pious labors among the Indians in the

vicinity of Edmonton. Mr. Rundle once visited this region and remained

camped for a considerable time near the base of Cascade Mountain,

probably shortly after Sir George Simpson explored this-region. The work

of Mr. Rundle among the Indians appears to have been highly successful,

if one may judge by the present condition of the Stoneys, who are

honest, truthful, and but little given to the vices of civilization.

Even to this day the

visitor may see them at Banff dressed in partly civilized, partly savage

attire, or on rare occasions decked out in all the feathers and beaded

belts and moccasins that go to make up the sum total of savage splendor.

Our attention comes at

last to Dr. Hector, who was connected with the Palliser expedition. It

is exceedingly unfortunate that the blue-book in which the vast amount

of useful information and interesting adventure connected with this

expedition is so clearly set forth should be now almost out of print.

There are no available copies in the United States or Canada and but

very few otherwise accessible. Dr. Hector followed up the Bow River and

passed the region now occupied by Banff in the year 1858. He was

accompanied by the persevering and ever popular botanist, Bourgeau.

Under the magic spell of close observation and clear description, the

most commonplace affairs assume an unusual interest in all of Dr.

Hector’s reports. It is very evident that game was much more abundant in

those early days than at present. For instance, Dr. Hector’s men shot

two mountain sheep near the falls of the Bow River, which are but a few

minutes walk from the hotel. Likewise when making a partial ascent of

the Cascade Mountain, Dr. Hector came on a large herd of these noble

animals, concerning which so many fabulous tales of their daring leaps

down awful precipices have been told. He also mentions an interesting

fact about the death of a mountain goat. An Indian had shot a goat when

far up on the slope of

Cascade Mountain, but

the animal, though badly wounded, managed to work its way around to some

inaccessible cliffs near the cascade. Here the poor animal lingered for

seven days with no less than five bullets in its body, till at length

death came and it fell headlong down the precipice. .

The climate of Banff

during the months of July and August is almost perfection. The high

altitude of 4500 feet above the sea-level renders the nights invariably

cool and pleasant, while the mid-day heat rarely reaches 8o° in the

shade. There is but little rain during this period and in fact there are

but two drawbacks,—mosquitoes and forest-fire smoke. The mosquitoes,

however, are only troublesome in the deep woods or by the swampy tracts

near the river. The smoke from forest fires frequently becomes so thick

as to obscure the mountains and veil them in a yellow pall through which

the sun shines with a weird light.

An effect of the high

northern latitude of this part of the Rocky Mountains is to make the

summer days very long. In June and early July the sun does not set till

nine o’clock, and the twilight is so bright that fine print can be read

out doors till eleven o’clock, and in fact there is more or less light

at midnight.

In June and September

one never knows what to expect in the way of weather. I shall give two

examples which will set forth the possibilities of these months, though

one must not imagine that they illustrate the ordinary course of events.

In the summer of 1895, after having suffered from a long period of

intensely hot weather in the east, I arrived at Banff on the 14th of

June. It was snowing and the station platform was covered to a depth of

six inches. The next day, however, I ascended Tunnel Mountain and found

a most extraordinary combination of summer and winter effects. The snow

still remained ten or twelve inches deep on the mountain sides, though

it had already nearly disappeared in the valley. Under this wintry

mantle were many varieties of beautiful flowers in full bloom, and, most

conspicuous of all, wild roses in profusion, apparently uninjured by

this unusually late snow-storm. I made a sad discovery near the top of

the mountain. Seeing a little bird fly up from the ground apparently out

from the snow, I examined more closely and observed a narrow snow-tunnel

leading down to the ground. Removing the snow I found a nest containing

four or five young birds all dead, their feeble spark of life chilled

away by the damp snow, while the mother bird had been, even when I

arrived, vainly trying to nurse them back to life.

This storm was said to

be very unusual for the time of year. The poplar trees in full summer

foliage suffered severely and were bent down to the ground in great

arches, from which position they did not fully recover all summer, while

the leaves were blighted by the frost. As a general rule, however,

mountain trees and herbs possess an unusual vitality, and endure syow

and frost or prolonged dry weather in a remarkable manner. The various

flowers which were buried for a week by this late storm appeared bright

and vigorous after a few warm days had removed the snow.

Toward the end of

September, 1895, there were two or three days of exceptionally cold

weather, the thermometer recording 6° Fahrenheit one morning. I made an

ascent of Sulphur Mountain, a ridge rising about 3,000 feet above the

valley, on the coldest day of that period. The sun shone out of a sky of

the clearest blue without a single cloud except a few scattered wisps of

cirrus here and there. The mountain summit is covered with a few

straggling spruces which maintain a bare existence at this altitude. The

whole summit of the mountain, the trees, and rocks were covered by a

thick mantle of snow, dry and powdery by reason of the severe cold. The

chill of the previous night had condensed a beautiful frost over the

surface of the snow everywhere. Shining scales of transparent ice, thin

as mica and some half-inch across, stood on edge at all possible angles

and reflected the bright sunlight from thousands of brilliant surfaces.

This little glimpse of winter was even more pleasing than the view from

the summit, for the mountains near Banff do not afford the mountain

climber grand panoramas or striking scenery. They tend to run in long

regular ridges, uncrowned by glaciers or extensive snow-fields.

A never failing source

of amusement to the residents of Banff, as well as to those more

experienced in mountain climbing, is afforded by those lately arrived

but ambitious tourists who look up at the mountains as though they were

little hills, and proceed forthwith to scale the very highest peak on

the day of their arrival. A few years ago some gentlemen became

possessed of a desire to ascend Cascade Mountain and set off with the

intention of returning the next day at noon. Instead of following the

advice of those who knew the best route, they would have it that a

course over Stoney Squaw Mountain, an intervening high ridge, was far

better. They returned three days later, after having wandered about in

burnt timber so long that, begrimed with charcoal, they could not be

recognized as white men. It is not known whether they ever so much as

reached the base of Cascade Mountain, but it is certain that they

retired to bed upon arriving at the hotel and remained there the greater

part of the ensuing week.

Cascade Mountain,

however, is a difficult mountain to ascend, not because there are steep

cliffs or rough places to overcome, but because almost every one takes

the wrong slope. This leads to a lofty escarpment, and just when the

mountaineer hopes to find himself on the summit, the real mountain

appears beyond, while a great gulf separates the two peaks and removes

the possibility of making the ascent that day.

Banff, with its fine

drives and beautiful scenery, its luxurious hotels and delightful

climate, will ever enjoy popularity among tourists. The river above the

falls is wide and deep and flows with such gentle current as to render

boating safe and delightful.’ The Vermilion lakes, with their low reedy

shores and swarming wild fowl, offer charming places for the canoe and

oarsman, at least when the mosquitoes, the great pest of our western

plains and mountains, temporarily disappear. Nevertheless, the climate

of Banff partakes of the somewhat dryer nature of the lesser and more

eastern sub-ranges of the Rocky Mountains. There is not sufficient

moisture to nourish the rich forests, vast snow-fields, and thundering

glaciers of the higher ranges to the west, which in imagination we shall

visit in the ensuing chapters.

RUNDLE MOUNTAIN AND BOW RIVER

|