|

Surroundings of the

Lake—Position of Mountains and Valleys—The Spruce and Balsam Firs—The

Lyall's Larch—Alpine Flowers—The Trail among the Cliffs—The Beehive, a

Monument of the Fast—Lake Agnes, a Lake of Solitude—Summit of the

Beehive—Lake Louise in the Distant Future.

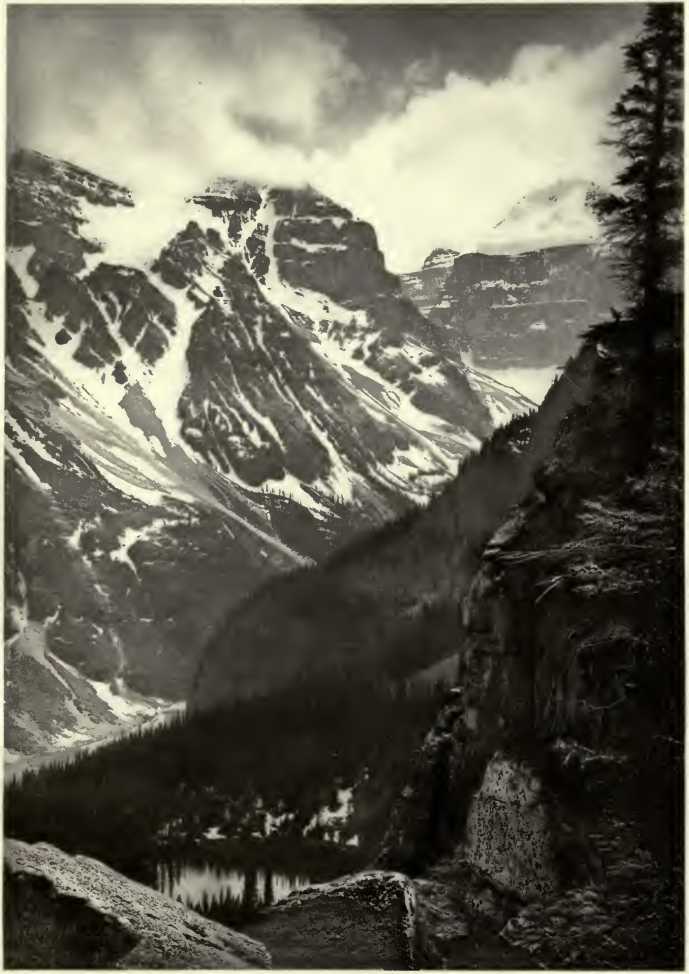

AMONG the mountains on

all sides of Lake Louise are many scenes of unusual beauty and grandeur.

While the lake itself must be considered the focal point of this region,

and is indeed wonderfully attractive by reason of its rare setting, the

encircling mountains are so rough and high, the valleys separating them

so deep and gloomy, yet withal- so beautiful, that the scenery

approaches perfection. The forces of nature have here wrought to their

utmost and thrown together in apparently wild confusion some of the

highest mountains in Canada and carved out gloomy gorge and rocky

precipice till the eye becomes lost in the complexity of it all. Lakes

and waterfalls reveal themselves among the rich dark forests of the

valleys, and afford beautiful foregrounds to the distant snow mountains

which seem to tower ever higher as one ascends.

A brief description of

the topography in the vicinity of Lake Louise would be now in place.

Southwestward from the lake is a range of very high and rugged mountains

covered with snow and glaciers. This range is the crest of the continent

of North America, in fact the great water-shed which divides the

Atlantic and Pacific drainage. In this range are many peaks over 11,000

feet above sea level, an altitude which is near the greatest that the

Rocky Mountains attain in this latitude. While farther south in Colorado

there are scores of mountains 13,000 or 14,000 feet high, it must be

remembered that no mountains in Canada between the International

boundary and the railroad have yet been discovered that reach 12,000

feet. Nevertheless, these mountains of lesser altitude are far more

impressive and apparently much higher because of their steep sides and

extensive fields of perpetual snow.

This great range,

forming the continental water-shed runs parallel to the general trend of

the Rocky Mountains of Canada, or about northwest and southeast. Several

spur ranges branch off at right angles from the central mass and run

northeast five or six miles. Between these spur ranges are short valleys

which all enter into the wide valley of the Bow. Lake Louise occupies

one of these lesser valleys.

The several lateral

valleys are all comparatively near Lake Louise and differ remarkably in

the character of the scenery and vegetation. One is beautiful and richly

covered with forests; another desolate and fearfully wild. The valley of

Lake Louise contains in all three lakes, of which the smallest is but a

mere pool, some seventy-five yards across.

Far up on the mountain

side to the north of Lake Louise two little lakes were discovered many

years ago. They are now to the visitor who spends but one day, almost

the chief point of interest in this region. The trail thither leads into

the dense forest from near the chalet and proceeds forthwith to indicate

its nature by rising steadily and constantly. The tall coniferous trees

cast a deep cool shade even on a warm day. So closely do the trees grow

one to another that' the climber is entirely shut out from the world of

mountains and surrounded by a primeval forest as he follows the winding

path. Among the forest giants there are two principal trees, the spruce

and the balsam fir. Each is very tall and slender and at a distance the

appearance of the two trees is closely similar. The spruce is the

characteristic tree of the Rockies and is found everywhere. It reaches a

height of 75 or 100 feet in a single tapering bole, closely beset with

small short branches bent slightly downward, as though better to

withstand the burden of snow in winter. In open places the lower

branches spread out and touch the ground, but in forests they die and

leave a free passage between the trees. The balsam tree is quite similar

but may be discerned by its smoother bark which is raised from

underneath by countless blisters each containing a drop of transparent

balsam. Here and there are a few tall pines rivalling the spruces and

firs in height but affording a strong contrast to them in their

scattered branches and larger needles.

The ground is covered

with underbrush tangled in a dense luxuriance of vegetable life and

partly concealing the ancient trunks of fallen trees long since covered

with moss and now slowly decaying into a red vegetable mold.

At length, after half

an hour of constant climbing, a certain indefinable change takes place

in the forest. The air is cooler, the trees grow wider apart, and the

view is extended through long vistas of forest trees. Presently a new

species of tree, like our Eastern tamarack, makes its appearance. It is

the Lyall’s larch, a tree that endures the rigors of a subalpine climate

better than the spruces and balsam firs, so that it soon becomes to the

climber among these mountains an almost certain indication of proximity

to the tree-line.

It is not far from the

truth to say that the Lyall’s larch is the most characteristic tree of

the Canadian Rockies. It is not found in the Selkirk Range just west of

the main range, and while it has indeed been found as far south as the

International boundary, it has not been discovered in the Peace River

valley to the north. Restricted in latitude, it grows on the main range

of the Rockies only at a great altitude. Here on the borderland between

the vegetable and mineral kingdoms it forms a narrow fringe at the

tree-line and in autumn its needles turn bright yellow and mark a

conspicuous band around all the cliffs and mountain slopes at about 7000

feet above sea level. Its soft needles, gathered in scattered fascicles,

are set along the rough and tortuous branches, affording a scanty shade

but permitting of charming glimpses of distant mountains, clouds, and

sky among its gray branches and light-green foliage. It seems incapable

of sending up a tall slender stem but branches out irregularly and

presents an infinite variety of forms. Possibly for this reason the

larch cannot contest with the slender spruces and firs of the valley,

where it would be crowded out of light and sun among its taller rivals.

Presently the trail

leads from out the forest and crosses an open slope where some years ago

a great snow-slide swept down and stripped the trees from the mountain

side. Here, 1200 feet above Lake Louise, the air feels sensibly cooler

and indicates an Alpine climate.

The mountains now

*reveal themselves in far grander proportions than from below, as they

burst suddenly on the view. Nature has already made compensation for the

destroyed forest by clothing this slope with a profusion of wild

flowers, though much different in character from those at Lake Louise.

Alpine plants and several varieties of heather, in varying shades of red

or pink and even white, cover the ground with their elegant coloring.

One form of heath resembles almost perfectly the true heather of

Scotland, and by its abundance recalls the rolling hills and flowery

highlands of that historic land. The retreating snow-banks of June and

July are closely followed by the advancing column of mountain flowers

which must needs blossom, bear fruit, and die in the short summer of two

months duration. One may thus often find plants in full blossom within a

yard of some retreating- snow-drift.

On reaching the farther

side of the bare track of the avalanche, the trail begins to lead along

the face of craggy cliffs like some llama path of the Andes. The mossy

ledges are in some places damp and glistening with trickling springs,

where the. climber may quench his thirst with the purest and coldest

water. Wherever there is the slightest possible foothold the trees have

established themselves, sometimes on the very verge of the precipice so

that their spreading branches lean out over the airy abyss while their

bare roots are flattened in the joints and fractures of the cliff or

knit around the rocky projections like writhing serpents.

More than four hundred

feet below is a small circular pond of clear water, blue and brilliant

like a sapphire crystal. Its calm surface, rarely disturbed by mountain

breezes, reflects the surrounding trees and rocks sharp and distinct as

it nestles in peace at the very base of a great rock tower—the Beehive.

Carved out from flinty sandstone, this tapering cone, if such a thing

there be, with horizontal strata clearly marked resembles indeed a giant

beehive. Round its base are green forests and its summit is adorned by

larches, while between are the smooth precipices of its sides too steep

for any tree or clinging plant. What suggestions may not this ancient

pile afford! Antiquity is of man; but these cliffs partake more of the

eternal—existing forever. Their nearly horizontal strata were formed in

the Cambrian Age, which geologists tell us was fifty or sixty millions

of years ago. Far back in those dim ages when the sea swarmed with only

the lower forms of life, the fine sand was slowly and constantly

settling to the bottom of the ocean and building up vast deposits which

now are represented by the strata of this mountain. Solidified and made

into flinty rock, after the lapse of ages these deposits were lifted

above the ocean level by the irresistible crushing force of the

contracting earth crust. Rain and frost and moving ice have sculptured

out from this vast block monuments of varied form and aspect which we

call mountains.

Just to one side of the

Beehive a graceful waterfall dashes over a series of ledges and in many

a leap and cascade finds its way into Mirror Lake. This stream flows out

from Lake Agnes, whither the trail leads by a short steep descent

through the forest. Lake Agnes is a wild mountain tarn imprisoned

between gloomy cliffs, bare and cheerless. Destitute of trees and nearly

unrelieved by any vegetation whatsoever, these mountain walls present a

stern monotony of color. The lake, however, affords one view that is

more pleasant. One should walk down the right shore a few hundred feet

and look to the north. Here the shores formed of large angular blocks of

stone are pleasantly contrasted with the fringe of trees in the

distance.

The solitary visitor to

the lake is soon oppressed with a terrible sensat\on of .utter

loneliness. Everything in the surroundings is gloomy and silent save for

the sound

of a trickling rivulet

which falls over some rocky ledges on the right of the lake. The faint

pattering sound is echoed back by the opposite cliffs and seems to fill

the air with a murmur so faint, and yet so distinct, that it suggests

something supernatural. The occasional shrill whistle of a marmot breaks

the silence in a startling and sudden manner. A visitor to this lake

once cut short his stay most unexpectedly and hastened back to the

chalet upon hearing one of these loud whistles which he thought was the

signal of bandits or Indians who were about to attack him.

Lake Agnes is a narrow

sheet of water said to be unfathomable, as indeed is the case with all

lakes before they are sounded. It is about one third of a mile in length

and occupies a typical rock basin, a kind of formation that has been the

theme of heated discussion among geologists. The water is cold, of a

green color, and so pellucid that the rough rocky bottom may be seen at

great depths. The lake is most beautiful in early July before the

snowbanks around its edge have disappeared. Then the double picture,

made by the irregular patches of snow on the bare rocks and their

reflected image in the water, gives most artistic effects.

From the lake shore one

may ascend the Beehive in about a quarter of an hour. The pitch is very

steep but the ascent is easy and exhilarating, for the outcropping

ledges of sandstone seem to afford a natural staircase, though with

irregular steps. Everywhere are bushes and smaller woody plants of

various heaths, the tough strong branches of which, grasped in the hand,

serve to assist the climber, while occasional trees with roots looped

and knotted over the rocks still further facilitate the ascent.

Arrived on the flat

summit, the climber is rewarded for his toil. One finds himself in a

light grove of the characteristic Lyall’s larch, while underneath the

trees, varipus ericaceous plants suggest the Alpine climate of the

place.

Though the climber may

come here unattended by friends, he never feels the loneliness as at

Lake Agnes. There the gloomy mountains and dark cliffs seem to surround

one and threaten some unseen danger, but here the broader prospect of

mountains and the brilliancy of the light afford most excellent company.

I have visited this little upland park very many times, sometimes with

friends, sometimes with the occasional visitors to Lake Louise, and

often alone. The temptation to select a soft heathery seat under a fine

larch tree and admire the scenery is irresistible. One may remain here

for hours in silent contemplation, till at length the rumble of an

avalanche from the cliffs of Mount Lefroy awakens one from reverie.

The altitude is about

7350 feet above sea level and in general this is far above the tree

line, and it is only that this place is unusually favorable to tree

growth that such a fine little grove of larches exists here.

Nevertheless, the summer is very brief—only half as long as at Lake

Louise, 1700 feet below. The retreating snow-banks of winter disappear

toward the end of July and new snow often covers the ground by the

middle of September. How could we expect it to be otherwise at this

great height and in the latitude of Southern Labrador? On the hottest

days, when down in the valley of the Bow the thermometer may reach

eighty degrees or more, the sun is here never oppressively hot, but

rather genially warm, while the air is crisp and cool. Should a storm

pass over and drench the lower valleys with rain, the air would be full

of hail or snow at this altitude. The view is too grand to describe, for

while there is a more extensive prospect than at Lake Louise the

mountains appear to rise far higher than they do at that level. The

valleys are deep as the mountains high, and in fact this altitude is the

level of maximum grandeur. The often extolled glories of high mountain

scenery is much overstated by climbers. What they gain in extent they

lose in intent. The widened horizon and countless array of distant peaks

are enjoyed at the expense of a much decreased interest in the details

of the scene. In my opinion one obtains in general the best view in the

Canadian Rockies at the tree line or slightly below. Nevertheless every

one to his own taste.

The most thrilling

experience to be had on the summit of the Beehive is to stand at the

verge of the precipice on the east and north sides. One should approach

cautiously, preferably on hands and knees, even if dizziness is unknown

to the climber, for from the very edge the cliff drops sheer more than

600 feet. A stone may be tossed from this place into the placid waters

of Mirror Lake, where after a long flight of 720 feet, its journey’s end

is announced by a ring of ripples far below.

Lake Louise appears

like a long milky-green sheet of water, with none of that purity which

appears nearer at hand. The stream from the glacier has formed a

fanshaped delta, and its muddy current may be seen extending far out

into the lake, polluting its crystal water and helping to fill its basin

with sand and gravel till in the course of ages a flat meadow only will

mark the place of an ancient lake.

There are even now many

level meadows and swampy tracts in these mountains which mark the

filled-up bed of some old lake. These places are called “ muskegs,” and

though they are usually safe to traverse, occasionally the whole surface

trembles like a bowl of jelly and quakes under the tread of men and

horses. In such places let the traveller beware the treacherous nature

of these sloughs, for on many an occasion horses have been suddenly

engulfed by breaking through the surface, below which deep water or

oozy-mud offers no foothold to the struggling animal.

At the present rate of

filling, however, the deep basin of Lake Louise will require a length of

time to become obliterated that is measured by thousands of years rather

than by centuries,—a conception that should relieve our anxiety in some

measure. |