|

Mount

Assiniboine—Preparations for Visiting it—Camp at Heely's Creek—Crossing

the Simpson Pass—Shoot a Pack-Horse—A Delightful Camp—A Difficult Snow

Pass—Burnt Timber—Nature Sounds—Discovery of a Beautiful Lake—Inspiring

View of Mount Assiniboine— Our Camp at the Base of the Mountain—Summer

Snow-Storms—Inaccessibility of Mount Assiniboine.

GREAT interest was

aroused among tourists in the summer of 1895, by the reports of a

remarkable peak south of Banff named Mount Assiniboine. According to

current accounts, it was the highest mountain so far discovered between

the International boundary and the region of Mounts Brown and Hooker.

Besides its great altitude, it was said to be exceedingly steep on all

sides, and surrounded by charming valleys dotted with beautiful lakes.

The time required to reach the mountain with a camping outfit and

pack-horses was said to be from five to seven days.

The romance of visiting

this wild and interesting region, hitherto but little explored, decided

me to use one month of the summer season in this manner. By great good

fortune I met, at Banff, two gentlemen likewise bent on visiting the

same region, and on comparing our prospective plans, it appeared that

mutual advantage would be gained by joining our forces. In this way we

would have the pleasure of a larger company, and at the same time the

opportunity of separating, should we come to a disagreement.

The sixth of July was

decided on as the date for our departure. In the meantime, we made

frequent visits to the log-house of our outfitter, Tom Wilson, who was

to supply us with horses, our entire camping outfit, and guides. Many

years previously, Wilson had packed for the early railroad surveyors,

and had thus gained a valuable experience in all that concerns the

management and care of pack-animals among the difficulties of mountain

trails. In the past few years, he has been engaged in supplying tourists

with camping outfits and guides, for excursions among the mountains.

The season of 1895 was

very backward, and there was an unusually late fall of snow at Banff, in

the middle of June. Moreover, the weather had remained so cold that the

snow on the higher passes still remained very deep, and several bands of

Indians, who attempted to cross the mountains with their horses late in

June, were repulsed by snow six or eight feet deep.

The weather continued

cold and changeable during the first week in July. In the meanwhile,

however, our preparations for departure went on without interruption,

and Wilson’s log-house, where the supplies and camp outfits were safely

stored, became a scene of busy preparation.

On every side were to

be seen the various necessaries of camp life: saddles for the horses,

piles of blankets, here and there ropes, tents, and hobbles. Great heaps

of provisions were likewise piled up in apparent confusion, though, in

reality, every item was portioned out and carefully calculated. Rashers

of bacon and bags of flour comprised the main bulk of the provisions,

but there were, besides, the luxuries of tea, coffee, and sugar, in

addition to large quantities of hard tack, dried fruits and raisins,

oatmeal, and cans of condensed milk. Pots and pails, knives, forks, and

spoons, and the necessary cooking utensils were collected in other

places. Our men were already engaged for the trip, and were now busily

moving about, seeing that everything was in order, the saddle girths,

hobbles, and ropes in good condition, the axes sharp, and the rifles

bright and clean.

At length the sixth of

July came, but proved showery and wet like many preceding days.

Nevertheless, our men started in the morning for the first camp, which

was to be at Heely’s Creek, about six miles from Banff. Our prospective

route to Mount Assiniboine was, first, over the Simpson Pass to the

Simpson River, and thence, by some rather uncertain passes, eastward,

toward the region of the mountain.

Toward the middle of

the afternoon we started on foot for Heely’s Creek, where our men were

to meet us and have the camp prepared. Passing northward up the valley,

we followed the road by the famous Cave and Basin, where the hot sulphur

water bubbles up among the limestone formations which they have

deposited round their borders. The Cave appears to be the cone or crater

of some extinct geyser, and now a passage-way has been cut under one

wall, so that bathers may enjoy hot baths in this cavern. A single

opening in the roof admits the light.

A short time after

leaving these interesting places, we had to branch off from the road,

and plunge into a burnt forest, where there was supposed to be a trail.

The trail soon faded away into obscurity among the maze of logs, and,

worse still, it now came on to rain gently but constantly. After an hour

or more of hard work we came to Heely’s Creek.

The

camp was on the farther side of the creek, and, after shouting several

times, Peyto, our chief packer, came dashing down on horseback, and

conveyed us, one at a time, across the deep, swift stream. Peyto made an

ideal picture of the wild west, .mounted as he was on an Indian steed,

with Mexican stirrups. A great sombrero hat pushed to one side, a

buckskin shirt ornate with Indian fringes on sleeves and seams, and

cartridge belt holding a hunting knife and a six-shooter, recalled the

romantic days of old when this was the costume throughout the entire

west. The

camp was on the farther side of the creek, and, after shouting several

times, Peyto, our chief packer, came dashing down on horseback, and

conveyed us, one at a time, across the deep, swift stream. Peyto made an

ideal picture of the wild west, .mounted as he was on an Indian steed,

with Mexican stirrups. A great sombrero hat pushed to one side, a

buckskin shirt ornate with Indian fringes on sleeves and seams, and

cartridge belt holding a hunting knife and a six-shooter, recalled the

romantic days of old when this was the costume throughout the entire

west.

Our encampment

consisted of three tents, prettily grouped among some large spruce

trees. A log fire was burning before each tent, and, on our arrival, the

cooks began to prepare our supper. This was my first night in a tent for

a year, and the conditions were unfavorable for comfort, as we were all

soaked through by our long tramp in the bush, and, moreover, it was

still raining. Nevertheless, we were all contented and happy, our

clothes soon dried before the camp fires, and after supper we sang a few

popular songs, then rolled up in warm blankets on beds of balsam boughs,

and slept peacefully till morning.

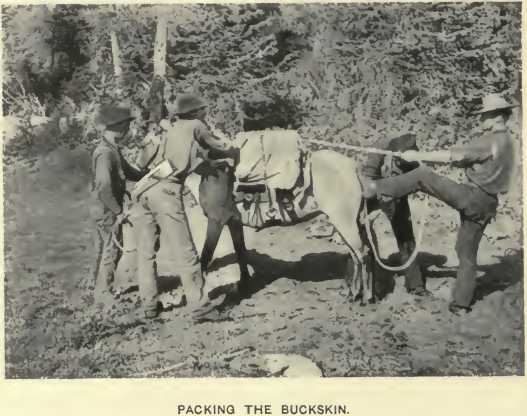

I

was awakened at dawn by the cry of “Breakfast is ready,” and prepared

forthwith to do it justice. The day appeared cloudy but not very

threatening. In an hour the packers began their work, and it was

wonderful to observe the system and rapidity of their movements. The

horses, of which we had seven as pack-animals and two for the saddle,

were caught and led to the camp, where they were tied to trees near by.

All the provisions, tents, cook boxes, bags, and camp paraphernalia were

then made ready for packing. There are three prime requisites in skilful

packing. They are: the proper adjustment of the blanket and saddle so

that it will neither chafe the back of the horse nor slip while on the

march; the exact balancing of the two packs ; and the knowledge of the

“diamond hitch.” The wonderful combination of turns and loops which go

to make up the diamond hitch has always been surrounded with a certain

secrecy, and jealously guarded by those initiated into the mysteries of

its formation. It was formerly so essential a part of the education of a

Westerner that as much as one hundred dollars have been paid for the

privilege of learning it. Without going into details, it may be

described as a certain manner of placing the ropes round the packs,

which, once learned, is exceedingly simple to tie on or take off, and it

will hold the pack in place under the most trying circumstances. The

name is derived from a diamond-shaped figure formed by the ropes between

the packs. I

was awakened at dawn by the cry of “Breakfast is ready,” and prepared

forthwith to do it justice. The day appeared cloudy but not very

threatening. In an hour the packers began their work, and it was

wonderful to observe the system and rapidity of their movements. The

horses, of which we had seven as pack-animals and two for the saddle,

were caught and led to the camp, where they were tied to trees near by.

All the provisions, tents, cook boxes, bags, and camp paraphernalia were

then made ready for packing. There are three prime requisites in skilful

packing. They are: the proper adjustment of the blanket and saddle so

that it will neither chafe the back of the horse nor slip while on the

march; the exact balancing of the two packs ; and the knowledge of the

“diamond hitch.” The wonderful combination of turns and loops which go

to make up the diamond hitch has always been surrounded with a certain

secrecy, and jealously guarded by those initiated into the mysteries of

its formation. It was formerly so essential a part of the education of a

Westerner that as much as one hundred dollars have been paid for the

privilege of learning it. Without going into details, it may be

described as a certain manner of placing the ropes round the packs,

which, once learned, is exceedingly simple to tie on or take off, and it

will hold the pack in place under the most trying circumstances. The

name is derived from a diamond-shaped figure formed by the ropes between

the packs.

By eight o’clock our

procession of ten horses was on the march, and, after passing through a

meadow where every blade of grass was hung with pendent drops of mingled

rain and dew, now sparkling bright in the morning sun, we came to the

trail. Our winding cavalcade followed near the creek and gradually rose

above its roaring waters, which dashed madly over many a cascade and

waterfall in its rocky course. Our pathway rose constantly and led us

through rich forests.

Peyto led the

procession mounted on an Indian horse called Chiniquy, not a very

noble-looking beast, but a veteran on the trail, and, by reason of his

long legs, a most trustworthy animal in crossing deep rivers. Then

followed the pack-horses with the men interspersed to take care of them,

and the rear was brought up by our second packer, likewise on horseback.

The greater part of the time, the gentlemen of the expedition kept in

the rear.

The flowers were in all

the glory of their spring-time luxuriance, and we discovered new

varieties in every meadow, swamp, and grove. Beside the several

varieties of anemones, the yellow columbines, violets, and countless

other herbaceous plants, we found, during the march of this day, six

kinds of orchids. Among them was the small and beautiful, purple

Calypso, which we found in bogs and damp woods, rearing its showy

blossom a few inches above the ground.

At the base is a single

heart-shaped leaf. We were very much pleased to find this elegant and

rare orchid growing so abundantly here. There is a certain regal

nobility and elegance pertaining to the whole family of orchids, which

elevates them above all plants,, and places them nearest to animate

creation. Whether we find them in high northern latitudes, in cold bogs,

or in dark forests, retreating far from the haunts of men, avoiding even

their own kind, solitary and unseen ; or perhaps crowded on the branches

of trees in a tropical forest, guarded from man by venomous serpents,

the stealthy jaguar, stinging insects and a fever-laden air; they

command the greatest interest of the botanist and the highest prices of

the connoisseur.

We camped at about two

o’clock, not far from the summit of the Simpson Pass, in a valley

guarded on both sides by continuous mountains of great height.

We were surprised the

next day, on reaching the summit, to find the pass covered with snow,

heaped in great drifts, ten or twenty feet deep, among the trees. The

Simpson Pass is only 6884 feet above tide, and, consequently, is below

the tree line. Near the summit were two small ponds still frozen over. A

warm sun and a genial south wind were, however, rapidly dissolving the

snow and reducing it to slush, while clear streams of water were running

in the meadows everywhere, regardless of regular channels.

As we began our descent

on the south side, a great change came over the scene. Two hundred feet

of descent brought us from this snowy landscape to warm mountain slopes,

where the grass was almost concealed by reason of myriads of yellow

lilies in full blossom, mingled with white anemones. These banks of

flowers, resembling the artificial creations of a hot-house, were

sometimes surrounded on all sides by lingering patches of snow. Such

constant and sudden change is characteristic of mountain climates, where

a few warm days suffice to melt the snow and coax forth the flowers with

surprising rapidity.

The trail now descended

rapidly, and led us through forests much denser and more luxuriant than

those on the other side of the pass. Everything betokened a moister

climate, and the character of the vegetation had changed so much that

many new kinds of plants appeared, while those with which we were

familiar grew ranker and larger. We had crossed the continental divide,

from Alberta into British Columbia.

Early in the afternoon

we came to our camping place on the banks of the Simpson River, where a

great number of teepee poles proved this to be a favorite resort among

the Indians. On all sides, the mountains were heavily forested to a

great height, and, far above, gray limestone cliffs rose in bare

precipices nearly free of snow.

On July the ninth, we

made the longest and most arduous march so far taken. Our route, at

first, lay down the Simpson River for several miles. While the horses

and men followed-the river bed almost constantly, making frequent

crossings to avail themselves of better walking and short cuts, t}ie

rest of us necessarily remained on one bank, and were compelled to make

rapid progress to keep up with our heavily laden horses.

After we had proceeded

down the winding banks of the Simpson River for about two hours, our

pass, a mere notch in the mountains, was descried by Mr. B., who had

visited this region two years before in company with Wilson. The pass

lay to the east, and it was necessary for every one to cross the river,

which was here a very swift stream nearly a yard in depth. We all got

across in safety, but had not advanced into the forest on the farther

side more than fifty yards, when one of my pack-horses fell, by reason

of the rough ground, and broke a leg. It required but a few minutes to

unpack the poor beast and end his career with a rifle bullet. The packs

were then placed on old Chiniquy, the faithful beast hitherto used by

Peyto as a saddle-horse.

In less than fifteen

minutes we were ready to proceed again. The trail now led us up very

steep ascents on a forest-clad mountain slope for several hours. After

this we entered a gap in the mountains and followed a stream for many

miles, and at length pitched our camp late in the afternoon, after

having been on the march for nine hours.

Every one was rejoiced

at the prospect of a rest and something to eat. Even the horses, so soon

as their packs and saddles were removed, showed their pleasure by

rolling on the ground before hastening off to a meadow near by. Axes

were busy cutting tent poles and firewood. Soon the three tents were

placed in position; and fires were burning brightly before each, while

the cooks prepared dinner.

This place was most

delightful. The immediate ground was quite level and grassy. Near by was

a clear deep stream with a gentle, nearly imperceptible current, which

afforded a fine place fora cold plunge. The mountains hemmed in a valley

of moderate width and presented a continuous barrier on either side for

many miles. The general character of the scenery was like that of the

Sierra Nevadas, with high cliffs partly adorned with trees and shrubs,

down which countless waterfalls fell from heights so great, that they

resembled threads of silver, waving from side to side in the changing

currents of air. On the mountain side south of our camp, there stood a

remarkable castle or fortress of rock, where nature had apparently

indulged her fancy in copying the works of men. So perfect was the

representation, that no aid from the imagination was required to see

ramparts, embrasures, and turreted fortifications of a castle, in the

remarkable pinnacles and clefts cut out by nature from the horizontal

strata. The next morning, every one was more or less inspired with a

pleasing anticipation and excitement, as, according to reports, we had

not far to go before we should get our first view of Mount Assiniboine.

At the end of our valley was a pass, from the summit of which Mount

Assiniboine could be seen. The trail led us through a forest with but

little underbrush, and presently a beautiful lake burst on our view. Two

of us, being somewhat in advance of the pack train, caught a dozen fine

trout here in a very short time, and were only interrupted by the

arrival of the horses and men. The fish were so numerous that they could

be seen everywhere on the bottom, and at the appearance of our

artificial flies on the water, several fish would rise at once.

In half an hour, the

summit of our pass appeared over the tree tops, and rose, apparently,

500 feet higher. The state of the pass was, however such as to cool our

enthusiasm decidedly. It was completely covered with snow to a great

depth, which made it seem probable that we would not succeed in getting

the horses over. As this could not be proved from our position, we

pushed on, determined to overcome all difficulties. The snow began to

appear, at first, in small patches in shady places among the forest

trees, then in large drifts and finally, everywhere except on the most

exposed slopes. The trail had been lost for some time, buried deep in

the snow. Our progress was not difficult, however, as the forest had

assumed the thin and open nature characteristic of high altitudes, and

it was possible to proceed in any direction. Our horses struggled on

bravely, and by dint of placing all the men in front and breaking down a

pathway, we managed to effect passages over long stretches where the

snow was five or six feet deep. After the tree line had been reached, we

were more fortunate, as a long narrow stretch, free of snow led quite to

the top of the pass, through the otherwise unbroken snow fields. A great

cornice of snow appeared on our right near the top of the pass and

showed a depth of more than forty feet.

Near

the top of the pass the travelling was much easier, and in a few minutes

we were looking over the summit across a wide valley to a range of rough

mountains hung with glaciers. Beyond them, and rising far above, could

be seen the sharp crest of Mount Assiniboine, faintly outlined against •

the sky in a smoky atmosphere. The intervening wide valley revealed a

great expanse of burnt forest. The dreary waste of burnt timber was only

relieved by two lakes, several miles distant, resting in a notch among

the mountains. Near

the top of the pass the travelling was much easier, and in a few minutes

we were looking over the summit across a wide valley to a range of rough

mountains hung with glaciers. Beyond them, and rising far above, could

be seen the sharp crest of Mount Assiniboine, faintly outlined against •

the sky in a smoky atmosphere. The intervening wide valley revealed a

great expanse of burnt forest. The dreary waste of burnt timber was only

relieved by two lakes, several miles distant, resting in a notch among

the mountains.

The nearer was about a

mile in length, while slightly beyond, and at a higher elevation, was

the second, a mere pool of dark blue water, resting against the moraine

of a glacier.

In the valley, a meadow

near a large stream seemed to offer the best chances for a camp. In an

hour we reached this spot after a hard descent. Some of our horses

displayed great sagacity in selecting the safest and easiest passages

between and around the logs, and gave evidence of their previous

experience in this kind of work.

In order to rest the

men and horses, after the arduous marches of the past forty-eight hours,

we decided to remain an entire day at this place. We were also anxious

to explore the two lakes, as they seemed to offer fair promise of

beautiful scenery and interesting geological formation. Our camp was

surrounded on all sides by burnt forests and charred logs, and so

offered but little of the picturesque. A partial compensation was

enjoyed, however, by reason of the great variety and number of song

birds which were now nesting in a small swamp near by. This bog was

clothed in a rich covering of grass, and here our horses revelled in the

abundance of feed, while some small bushes scattered here and there

afforded shelter and homes for several species of birds. All day long

and even far into the night we were entertained by their melodies. The

most persistent singer of all was the white-crested sparrow, whose sweet

little air of six notes was repeated every half minute throughout the

entire day, beginning with the first traces of dawn. Perhaps our

attention was more attracted to the sounds about us because there was so

little to. interest the eye in this place. Smoke from distant forest

fires obscured whatever there was in the way of mountain scenery, while

the waste of burnt timber was most unattractive. A warm, soft wind blew

constantly up the valley and made dull moanings and weird sounds among

the dead trees, where strips of dried bark or splinters of wood vibrated

in the breeze. The rushing stream, fifty yards from our camp, gave out a

constant roar, now louder, now softer, according as the wind changed

direction and carried the sound towards or away from us. The thunders of

occasional avalanches, the loud reports of stones falling on the

mountain sides, were mingled with the varied sounds of the wind, the

rustling of the grass, the moaning trees, and the songs of birds. These

were all pure nature sounds, most enjoyable and elevating. Though but

partially appreciated at the time, such experiences linger in the memory

and help make up the complex associations of pleasures whereby one is

led to return again and again to the mountains, the forests, and the

wilderness.

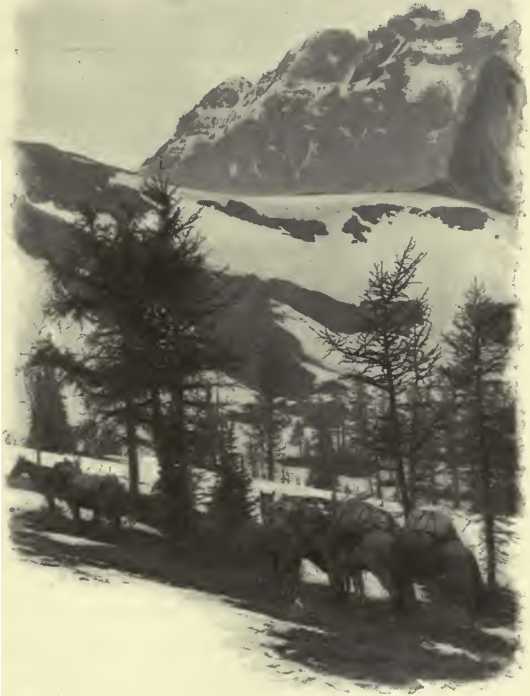

Our time, which was set

aside for this region, now being consumed, we started on July the

twelfth for the valley at the base of Mount Assiniboine, where it was

probable that we should camp for a period of two weeks or more. Our

route lay toward the end of the valley and thence around a projecting

spur of the mountain which cut off our view. In about two hours our

horses were struggling up the last steep slope near the summit of the

divide. I had delayed for a photograph of a small lake, so the horses

and men were ahead. When at length I gained the top I found that a

misplaced pack had caused delay, and so I overtook the entire party on

the borders of a most beautiful sheet of water. The transformation was

nearly instantaneous. The burnt timber was completely shut out from view

by the low ridge we had just passed over, and we entered once more a

region of green forests. The lake was long and narrow ; on the farther

side, hemmed in by rock slides and cliffs of the mountains, but on the

west side a trail led along the winding shore among larch and spruce

trees. In many shady nooks along the banks of the lake were snow-drifts,

under the trees or behind protecting rocks. So long had winter lingered

this season that part of the lake was still covered with ice. Large

fragments of ice were drifting down the lake and breaking among the

ripples. Near the shore in some places, the water was filled with

thousands of narrow, needle-like pieces of ice several inches long and

perhaps thick as a match, which, by their rubbing together in the moving

water, made a gentle subdued murmur like the rustling of a silken gown.

When ice is exposed to a bright sun for several days, it shows its

internal structure by separating into vertical columns, with a grain

like that of wood. The ice needles which we saw had been formed during

the last stages of this wonderful process.

The Indians had made a

most excellent trail round the lake, as frequently happens in an open

country. Wherever dense brush or much fallen timber occur, the trail

usually disappears altogether, only to be discovered again where there

is less need for it. It is said that a trail, once made, will be

preserved by the various game animals of the. country. In fact, there

were quite recent tracks of a mountain goat in the path we followed

around the lake.

The trail closely

followed the waters edge and led us to the extreme end of the lake and

thence eastward, where, having left this beautiful sheet of water, we

passed through a grove for a very short space and came at once to

another smaller, and possibly still more beautiful, sheet of water.

Simultaneously the magnificent and long-expected vision of Mount

Assiniboine appeared. It was a most majestic spire or wedge of rock

rising out of great snow fields, and resembling in a striking manner the

Matterhorn of Switzerland.

It would be impossible

to describe our feelings at this sight, which at length, after several

days of severe marching, now suddenly burst upon our view. The shouts of

our men, together with the excitement and pleasure depicted in every

face, were sufficient evidence of our impressions. After a short pause,

while we endeavored to estimate the height and distance and gain some

true idea of the mountain, all moved on rapidly through alternating

groves and meadows to our camping place. This was at length selected

about a half mile from the place where we first saw Mount Assiniboine.

Here was a lake nearly a mile long, which reached up nearly to the base

of the mountain, from which it was separated by a glacier of

considerable size. Our camp was on a terrace above the lake, near the

edge of a forest. A small stream ran close to our tent, from which we

could obtain water for drinking and cooking purposes. The lake was in

the bottom of a wide valley, which extended northwards from our camp for

several miles, and then opened into another valley running east and

west. The whole place might be described as an open plain among

mountains of gentle slope and moderate altitudes, grouped about

Assiniboine and its immediate spurs.

Our camp was 7000 feet

above sea-level, and this was the mean height of the valley in all this

vicinity. On mountain slopes this would be about the upper limit of tree

growth, but here, owing to the fact that the whole region was elevated,

the mean temperature was slightly increased, and we found trees growing

as high as 7400 or 7500 feet above sea-level. Nevertheless, the general

character of the vegetation was sub-alpine. Many larches were mingled

with the balsam and spruce trees in the groves, and extensive areas were

destitute of trees altogether. These moors were clothed with a variety

of bushy plants, mostly dwarfed by the rigor of the climate, while here

and there a small balsam tree could be seen, stunted and deformed by its

long contest for life, and bearing many dead branches among those still

alive. These bleached and lifeless limbs, with their thick, twisted

branches resisting the axe, or even the approach of a wood-cutter,

resembled those weird and awful illustrations of Dore, where evil

spirits in the infernal regions are represented transformed to trees.

Curiously enough, the

trees in the groves were more or less huddled together, as though for

mutual protection. The outlying skirmishers of balsam or spruce were

undersized, and often grew in natural hedges, so regular that not one

single branchlet projected beyond the smooth surface, as if sensitive of

the wind and cold. The vegetable world does not naturally excite our

sympathy, but this exhibition of, as it were, a united resistance

against the elements was almost pitiable.

Snow banks surrounded

our camp and appeared everywhere in the valley. The lake was not

entirely free of ice, and large pieces of snow and ice, dislodged from

the shores, were drifting rapidly down the lake, driven on by a strong

wind and large waves. The whole picture resembled a miniature Arctic

sea, where the curiously formed pieces of ice, often T-shaped and arched

over the water, recalled the characteristic forms of icebergs.

It was at first

impossible to explain where this never-failing supply of ice came from.

What was our surprise, on making an exploration of the lake, to find

that it had no outlet and was rapidly rising ! The snow banks and masses

of ice near the glacier were being gradually lifted up and broken off by

the rising water, and so floated down the lake.

We remained at Camp

Assiniboine for two weeks. During this time we ascended many of the

lesser peaks in the vicinity, and made excursions into the neighboring

valleys on all sides. The smoke only lasted one day after our arrival,

but, unfortunately, the weather during the 'first week was very

uncertain and fickle. A succession of storms, very brief but often

severe, swept over the mountains and treated us to a grand exhibition of

cloud and storm effects on Mount Assiniboine. Sometimes the summit would

be clear, and sharply outlined against the blue sky, but suddenly a mass

of black clouds would advance from the west and envelope the peak in a

dark covering. Long streamers of falling snow or rain would then

approach, and in a few moments we would feel the effects at our camp.

During these mountain storms the wind blows in furious gusts, the air is

filled with snow or sometimes hailstones, while thunder and lightning

continue for the space of about ten minutes. The clouds and storm

rapidly pass over eastward, and the wind falls, while the sun warms the

air, and in a few minutes removes every trace of hail or snow. Thus we

were often treated to winter and summer weather, with all the gradations

between, several times over in the space of an hour.

It seemed impossible to

ascend Mount Assiniboine> guarded as it was by vertical cliffs and

hanging glaciers. Only one route appeared on this side of the mountain,

and this lay up the steep snow-covered slope of a glacier, guarded at

the top by a long sc hr unci and often swept by rocks from a moraine

above. It might be possible, having gained the top of this, to traverse

the great neve surrounding the rock peak of Mount Assiniboine. From the

snow fields the bare rock cliffs rise about 3,000 feet. The angle of

slope on either side is a little more than fifty-one degrees, a slope

which is often called perpendicular, and, moreover, as the strata are

horizontal, there are several vertical walls of rock, which sweep around

the entire north and west faces, and apparently make impassable

barriers.

NORTH LAKE—LOOKING NORTHWEST. |