|

Evidence of

Game—Discovery of a Mountain Goat—A Long Hunt— A Critical Moment—A

Terrible Fall—An Unpleasant Experience— Habitat of the Mountain Goat—A

Change of Weather—A Magnificent Panorama—Set out to Explore the

Mountain—Intense Heat of a Forest Fire—Struggling with Burnt Timber—A

Mountain Bivouac—Hope and Despair—Success at Last—Short

Rations—Topography of Mount Assiniboine— The Vermilion River—A Wonderful

Canyon—Fording the Bow River.

DURING our excursions

we met with but little game, though it was very evidently a region where

wild animals were abundant. The ground in many places was torn up by

bears, where they had dug out the gophers and marmots. Large pieces of

turf, often a foot or eighteen inches square, together with great stones

piled up and thrown about in confusion around these excavations, gave

evidence of the strength of these powerful beasts.

Higher up on the

mountains we saw numerous tracks of the mountain goat, and tufts of wool

caught among the bushes as they had brushed by them.

I was strolling through

the upper part of the valley late one afternoon, when my eye fell

suddenly on a mountain goat walking along the cliffs about a quarter of

a mile distant. I had no rifle at the time and so returned to camp for

one, meanwhile keeping well covered by trees and rocks. In a quarter of

an hour I was back again and saw the goat disappear behind a ledge of

rock about a half mile distant. The mountain goat always runs up in case

of danger, so that it is essential to get above them in order to hunt

successfully. I started forthwith to climb to a ledge about 200 feet

above the one on which the goat appeared. This involved an ascent of

some 600 feet, as the strata had a gentle dip southward toward Mount

Assiniboine, so that it was necessary to take the ledge at a higher

point and follow the downward slope. I was well covered by intervening

cliffs, and the wind was favorable. It seemed almost a certainty that I

should get a shot by following this ledge for about a mile. Accordingly

I moved rapidly at first, and afterwards more cautiously, expecting to

see the goat at any moment. At length I came to a narrow gorge,

partially filled with snow, where there were fresh tracks leading both

up and down. On a further study of the problem, I saw fresh tracks in

the snow of the valley bottom, and knowing that it would be nearly

useless to go up for the goat, I took the alternative chance of finding

the animal below. After a hunt of two hours I returned to camp

completely baffled. Arrived there, I caught sight of the goat standing

unconcernedly on a still higher ledge.

It was now late in the

day, but after a good camp dinner I set off again, determined to have

that goat if it was necessary to stalk him all night. The animal was

resting on a ledge near the top of a precipice fully 250 feet in height.

I studied his position for at least a quarter of an hour, carefully

noting the snow patches on the ledge above, so that it would be easy to

recognize them on arriving there. Having made sure that I could

recognize the exact spot below which the goat was located, I started to

climb, and by a rough estimate calculated that I should have to ascend

at least 1000 feet. After a few hundred yards, I was completely hidden

from the goat in a shallow gully. Urged on by the excitement of the

hunt, I reached the ledge in twenty minutes and turned southward. I now

had to scramble over and among some enormous blocks of stone which had

fallen from the mountain side and were strewn about in wild disorder.

Some were twenty feet high, and between them were patches of snow which

often gave way very suddenly and plunged me into deep holes formed by

the snow melting back from the rock surfaces. Very soon I came to a

small pool of water and a trickling stream, already freezing in the

chill night air.

It was after nine

o’clock, though there was still a bright twilight in the northwest,

somewhat shaded, however, by the dark cliffs above. I proceeded very

slowly, so as to cool down somewhat and become a little steadier after

the rapid ascent. In about ten minutes I recognized the patch of snow

under which the goat was located, about one hundred yards ahead. I went

to the edge of the precipice cautiously, with rifle ready, and examined

the ledges below. The up-draught, caused by the sun during the daytime,

just now changed to the downward flow of the night air, chilled by

radiation on the mountain side. This I thought would arouse the goat,

but just at that moment my foot slipped and I dislodged a few pieces of

loose shingle, which went rattling down the cliffs. These stones made

the goat apprehensive of danger, in all probability, for I had no sooner

recovered my balance than I caught sight of the white head and shoulders

of the animal about twenty-five yards below. The animal stood motionless

and stared at me in a surprised but impudent manner. I took aim, but

could not keep the sight on him long enough to make sure of a shot, as

my rapid climb had made my nerves a trifle unsteady. Fortunately, the

goat showed not the slightest disposition to move and in a few seconds I

got a good aim and fired. As soon as the smoke cleared, I saw a dash of

white disappearing, and then heard a dull thud far below. A few seconds

later I saw the animal rolling over and over down the mountain side,

where it finally stopped on a slide of loose stones. I had to make a

long detour in order to get down to the animal, where I arrived in about

half an hour, and, remarkably enough, both horns were uninjured, though

the goat had fallen 125 feet before striking. This good luck resulted

from a small snow patch at the base of the cliff, which had broken the

force of the fall, and here there was a perfect impression of the

animal’s body, eighteen inches deep, in the hard snow, while the next

place where he had struck was about fifteen feet below.

It was about 10:30

o'clock when I started for camp, and so dark, at this, late hour, that

it was just possible to distinguish the obscure forms of rocks and trees

on the mountain side. There was still another ledge to be passed before

I could get down to the valley, where the only recognizable landmarks

were occasional snow patches, and a single bright gleam in the

darkness—our camp fire. I traversed northwards in descending, so as to

pass beyond the vertical ledge, and at length, thinking that I had gone

far enough, tried to descend. The place was steep, but as there were a

few bushes and trees a safe descent seemed practicable. So I unslung my

rifle, and, after resting it securely in a depression, I lowered myself

till my feet rested on a projection of rock below. At the next move

there was great difficulty in finding a rest for the rifle. At length I

found a fair place, and lowered myself again. One more step and I should

reach the bottom. Fortunately there was a stout balsam tree at the top

of the ledge, with great twisted roots above the rocks, which would

afford excellent hand-holds. Grasping them, after placing the rifle in

the lowest place, I lowered myself again, but to my surprise I could not

touch the bottom, and, looking down, found that I was hanging over a

ledge twenty feet high with rough stones below. Just then the rifle

began to slip down, as in my movements I had disturbed some bushes

supporting it. With one hand firmly grasping a stout root, and the toe

of my boot resting against the cliff, I took the rifle in my other hand,

and after a most tiresome struggle, succeeded at length in placing it

secure for the moment. It was now a hand-over-hand contest to get up. In

going down everything had seemed most firm and secure, but now it was

impossible to rely on anything, as the bushes broke away in my hand or

were pulled out by the roots, and the rocks all appeared loose or too

smooth to grasp. Necessity, however, knows no law, and after a most

desperate effort I regained the top of the cliff. Not relishing any more

experiences of this nature, I groped my way along for some distance and

finally found an easy descent. On reaching the valley, the snow patches

here and there afforded safe routes, illumined, as they were, by the

starlight. I reached camp after eleven o’clock tired but successful.

My men started at five

o’clock in the morning with ropes and a pole to bring down the game. It

was a fine young male, and we found the meat a most pleasing addition to

our ordinary fare. Goat meat has always had a bad reputation among

campers and explorers, by reason of its rank flavor. This, however,

probably depends on the age and sex of the animal, or the season of

year. In all those that I have tried there was merely a faintly sweet

flavor, which, however, is not at all apparent if the meat is broiled or

roasted, and it is then equal to very fair beef or mutton.

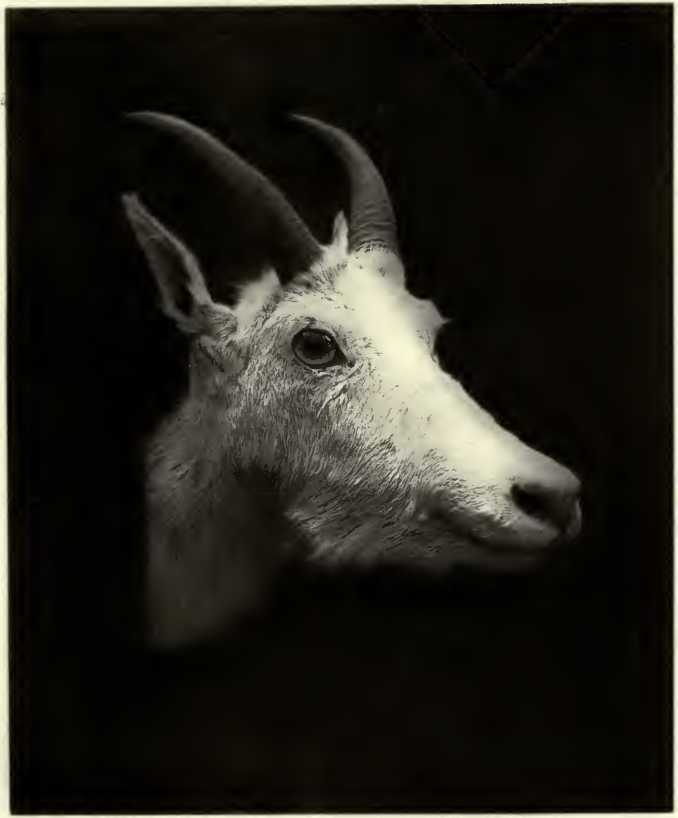

The mountain goat

inhabits the cliffs and snowy peaks of the Rockies, from Alaska to

Montana and Idaho, and thence southward in certain isolated localities.

Both sexes are furnished with sharp black horns curving gracefully

backwards. The muzzle and hoofs are jet black, but the wool is

snow-white, long, and soft, making a beautiful rug if the animal is

killed in winter. Then the hair becomes very long, and the soft thick

wool underneath is so dense as to prevent the fingers passing through.

Though these strange

animals resemble true goats to a remarkable degree, and the old males

sometimes have beards in winter, they are really a species of antelope,

closely related to the chamois of Switzerland. They do not resemble

those animals in wariness and intelligence, but are rather stupid and

slow in getting out of danger. They are, however, pugnacious, and, when

brought to bay, will often charge on the hunter and work fearful damage

with their sharp horns. The legs are exceedingly stout and so thickly

covered with long hair as to give the animal a clumsy appearance. Their

trails are almost always to be found traversing the mountain sides, far

above the tree line, at the bases of cliffs, and often passing over the

lowest depression into the next valley. These goat tracks are so well

marked that they often help the mountaineer, and sometimes lead him over

places where without their guidance it would be impossible to go. The

gait of the animal when running is a sort of gallop, which appears

rather slow, but when one considers the nature of the ground they

traverse, it is very rapid. The most inaccessible cliffs, frozen snow

fields, or crevassed glaciers offer no barriers to these surefooted

animals. I have seen a herd of several goats bounding along on the face

of the cliffs, where it did not appear from below that there could be

any possible foothold.

| |

Haunt OF THE MOUNTAIN GOAT.'

When a herd of

goats come to a gorge or passage of any kind where loose stones are

liable to be dislodged on those below, these skilful mountaineers

adopt the same plan of progress practised by human climbers. While

the herd remains below, under the protection of the cliffs, one goat

climbs the gully, and upon arriving at the top another follows, and

thus, one by one, all escape danger.

The mountain goat

is difficult to hunt by reason of the amount of climbing necessary

to get near them, or above them. They are far less wary than the

chamois of Switzerland, or the Rocky Mountain sheep. Nevertheless,

they seem to be endowed with a wonderful vitality, and are very hard

to kill. A goat not fatally wounded will often jump from a cliff on

which he is standing, and survive a considerable fall. A friend of

mine shot a goat near Lake Louise, which, after the first bullet,

rolled down a cliff more than thirty feet high and landed on its

feet at the bottom, where it proceeded to walk off as though nothing

unusual had happened. The animal I shot near Mount Assiniboine fell

125 feet, and then rolled 200 feet farther, and was still alive when

I reached him half an hour later.

These animals are by

far the most numerous of the big game in the Canadian Rockies, and are

said to be increasing in numbers. Their habits of frequenting high

altitudes and inaccessible parts of mountains will tend to preserve them

for many years from the relentless hunter.

After a week of fickle

weather with five inches of new snow on July 15th, there was a decided

change for the better, and the warm, bright days following one another

more regularly gave us the first taste of real summer that we had. The

massed drifts of snow diminished from day to day and the ice disappeared

from the lakes. Nature, however, tempered her delights by ushering in

vast numbers of mosquitoes and bull-dog flies to plague us. I was

engaged at this time in some surveying work, in order to determine the

height of Mount Assiniboine, and had to exercise the utmost patience in

sighting the instruments, surrounded by hundreds of voracious foes, and

often had to allow my face and hands to remain exposed to their stings

for several minutes.

We obtained the most

imposing view of Mount Assiniboine from the summit of a mountain about

five miles east of our camp. Standing at an altitude of 8800 feet, there

were eighteen lakes, large and small, to be seen in the various valleys,

which, together with the tumultuous ranges of the Rocky Mountains on

every side, some of them fifty or sixty miles distant, formed a

magnificent panorama.

From this point, which

was nearly due- north of Mount Assiniboine, the mountain shows an

outline altogether different from that seen at our camp MOUNT

assiniboine from northwest.

Here it forms a

magnificent termination of a stupendous wall or ridge of rock, about

11,000 feet high, which runs eastward for several miles, and then

curving around to the north, rises into another lofty peak nearly

rivalling Mount Assiniboine in height. A very large glacier sweeps down

from the neve on the north side of this lesser peak, and descends in a

crevassed slope to the valley bottom.

The valley just east of

us was quite filled by three lakes, the uppermost deep blue, the next

greenish, and a smaller one, farther north, of a yellowish color.

Our last exploit at

Mount Assiniboine was to walk completely around the mountain. We had

long desired to learn something of the east and south sides of this

interesting peak, and to effect this Mr. B., Peyto, and I started on

July 26th, determined to see as much as possible in a three days’ trip.

Our provisions consisted of bacon, hard tack, tea, sugar, and raisins.

Besides this we carried one blanket apiece, a small hand axe, and a

camera. As our success would depend in great measure on the rapidity of

our movements, we did not burden ourselves with ice-axes or firearms

except a six-shooter. After bidding farewell to Mr. P. and the other men

in camp, and telling them to expect us back in three days, we left our

camp at eight o’clock in the morning. We walked for three miles through

the open valleys to the north and east, and in about two hours stood at

the top of the pass, some 8000 feet above sea-level. From here we made a

rapid descent for about 2000 feet, to the largest lake of this

unexplored valley, which probably supplies one of the tributaries to the

Spray River. The change in the character of the vegetation was

remarkable. The trees grew to an immense size and reminded me strongly

of a Selkirk forest. We had a most difficult scramble here in the

pathless forest and up the opposite side of the valley. The heat was

oppressive, and we were glad to gain the level of another more elevated

valley where a cooler atmosphere greeted us. We held our way eastward

for several miles through a fine upland meadow, where the walking was

easy and the surroundings delightful. By noon we reached a small,

shallow lake near the highest part of the divide, considerably below

tree line. Here we decided to rest and have lunch. Mr. B. had explored

this region with one of his men a few days previously, and from him we

learned that we should have to struggle with burnt timber in a few

moments. The onward rush of the devastating fire had been stopped near

the pass, where the trees were small and scattered. After a short

descent we entered the burnt timber. I have never before seen a region

so absolutely devastated by fire as this. The fire must have burnt with

an unusually fierce heat, for it had consumed the smaller trees

entirely, or warped them over till they had formed half circles, with

their tops touching the ground. The outcrops of sandstone and quartz

rocks had been splintered into sharp-edged, gritty stones, covering the

ground everywhere like so many knives. The course of the valley now

turned rapidly to the south, so that we rounded a corner of the great

mass of mountains culminating in Mount Assiniboine. The mountain itself

had been for a long time shut out from view by an intervening lofty

ridge of glacier-clad peaks, which were, in reality, merely outlying

spurs.

The valley in which we

were now walking had an unusual formation, for after a short distance we

approached a great step, or drop, whereby the valley bottom made a

descent of 400 or 500 feet at an exceedingly steep pitch. Here it was

difficult to descend even in the easiest places. Arrived at the bottom

of the descent it was not very long before another appeared, far deeper

than the first. The mountains on either side, especially a most striking

and prominent peak on the east side of the valley, which had hitherto

appeared of majestic height, seemed to rise to immeasurable altitudes as

we plunged deeper and deeper in rapid descent.

The burnt timber

continued without interruption. Our passage became mere log walking, as

the extra exertion of jumping over the trees was worse than following a

crooked course on top of the prostrate trunks. This laborious and

exceedingly tiresome work continued for three hours, and at length the

charred trunks, uprooted or burnt off near the ground, and crossed in

every direction, were piled so high that we were often ten or twelve

feet above the ground, and had to work out our puzzling passage with

considerable forethought. At five o’clock our labors ended. We made a

camp near a large stream which appeared to take its source near Mount

Assiniboine. The only good thing about this camp was the abundance of

firewood, which was well seasoned, required but little chopping, and was

already half converted into charcoal. Under the shelter of an

overhanging limestone ledge we made three lean-tos by supporting our

blankets on upright stakes. Black as coal-heavers from our long walk in

the burnt timber, seeking a refuge in the rocky ledges of the mountains,

and clad in uncouth garments torn and discolored, we must have resembled

the aboriginal savages of this wild region. Some thick masses of

sphagnum moss, long since dried up, gave us a soft covering, to place on

the rough, rocky ground. Our supper consisted of bacon, hard tack, and

tea. Large flat stones laid on a gentle charcoal fire served to broil

our bacon most excellently, though the heat soon cracked the stones in

pieces.

At eight o’clock we

retired to the protection of our shelter. Overhead the starless sky was

cloudy and threatened rain. The aneroid, which was falling, indicated

that our altitude was only 4,700 feet above the sea. We arose early in

the morning; our breakfast was over and everybody ready to proceed at

seven o’clock. We were now on the Pacific slope, and, according to our

calculations, on one of the tributaries to the north fork of the Cross

River, which, in turn, is a tributary to the Kootanie.

We had a plan to

explore up the valley from which our stream issued, but beyond that, all

was indefinite. It was possible that this valley led around Mount

Assiniboine so that we could reach camp in two days. We were, however,

certain of nothing as to the geography of the region which we were now

entering.

The clouds covered the

entire sky and obscured the highest mountain peaks. Worse still, they

steadily descended lower and lower, a sign of bad weather. We had,

however, but this day in which to see the south side of Mount

Assiniboine, and consequently were resolved to do our best, though the

chances were much against us. For three hours we followed the stream

through the burnt timber, then the country became more open and our

progress, accordingly, more rapid. A little after ten o’clock we sat

down by the bank of the stream to rest for a few moments, and eat a

lunch of hard tack and cold bacon. Such fare may seem far from

appetizing to those of sedentary habits, but our tramp of three hours

over the fallen trees was equivalent to fully five or six hours walking

on a good country road, and what with the fresh mountain air and a light

breakfast early in the morning, our simple lunch was most acceptable.

A most pleasing and

encouraging change of' weather now took place. A sudden gleam of

sunlight, partially paled by a thin cloud, called our attention upward,

when to our great relief several areas of blue sky appeared, the clouds

were rising and breaking up, and there was every prospect of a change

for the better.

Once more assuming our

various packs, we pushed on with renewed energy. On the left or south

was a long lofty ridge of nearly uniform height. On the right was a

stupendous mountain wall of great height, the top of which was concealed

by the clouds. This impassable barrier seemed to curve around at the

head of the valley, and, turning to the south, join the ridge on the

opposite side. This then was a “blind” valley without an outlet. There

were two courses open to us. The first was to wait a few hours, hoping

to see Mount Assiniboine and return to camp the way we came. The second

was to force a passage, if possible, over the mountain ridge to the

south and so descend into the North Fork valley, which we were certain

lay on the other side. The latter plan was much preferable, as we would

have a better chance to see Mount Assiniboine, and the possibility of

returning to camp by a new route.

After a short

discussion, we selected a favorable slope and began to ascend the

mountain ridge. A vast assemblage of obstacles behind us in the shape of

two high passes, dense forests, and a horrid infinity of fallen trees,

crossed bewilderingly, made a picture in our minds, constant and vivid

as it was, that urged us forward. In striking contrast to this picture,

hope had built a pleasing air castle before us. We were now climbing to

its outworks, and should we succeed in capturing the place, a new and

pleasant route would lead us back to camp and place us there—so bold is

hope—perhaps by nightfall.

Thus with a repelling

force pushing from behind and an attractive force drawing us forward, we

were resolved to overcome all but the insuperable.

There was much of

interest on the mountain slope, which was gentle, and allowed us to pay

some attention to our surroundings. On this slope the scattered pine

trees had escaped the fire and offered a pleasant contrast to the burnt

timber. We passed several red-colored ledges containing rich deposits of

iron ore, while crystals of calcite and siderite were strewed

everywhere, and often formed a brilliant surface of sparkling,

sharp-edged rhombs over the dull gray limestone. Among the limestones

and shales we found fossil shells and several species of trilo-bites.

In an hour we had come

apparently to the top of our ridge, though of course we hardly dared

hope it was the true summit. As, one by one, we reached a commanding

spot, a blank, silent gaze stole over the face of each. To our dismay, a

vertical wall of rock, without any opening whatever, stood before us and

rose a half thousand feet higher. Thus were all our hopes dashed to the

ground suddenly, and we turned perforce, in imagination, to our weary

return over the many miles of dead and prostrate tree trunks that

intervened between us and our camp.

The main object of our

long journey was, however, at this time attained, for the clouds lifted

and revealed the south side of Mount Assiniboine, a sight that probably

no other white men have ever seen. I took my camera and descended on a

rocky ridge for some distance in order to get a photograph. Returning to

where my friends were resting, I felt the first sensation of dizziness

and weakness, resulting from unusual physical exertion and a meagre

diet. I joined the others in another repast of raisins and hard tack,

taken from our rapidly diminishing store of provisions.

Some more propitious

divinity must have been guiding our affairs at this time, for while we

were despondent at our defeat, and engaged in discussing the most

extravagant routes up an inaccessible cliff, our eyes fell on a well

defined goat trail leading along the mountain side on our left. It

offered a chance and we accepted it. Peyto set off ahead of us while we

were packing up our burdens, and soon appeared like a small black spot

on the steep mountain side. Having already passed several places that

appeared very dangerous, what was our surprise to see him now begin to

move slowly up a slope of snow that appeared nearly vertical. We stood

still from amazement, and argued that if he could go up such a place as

that, he could go anywhere, and that where he went we could follow. We

rushed after him, and found the goat trail nearly a foot wide, and the

dangerous places not so bad as they seemed. The snow ascent was

remarkably steep, but safe enough, and, after reaching the top, the goat

trail led us on, like a faithful guide pointing out a safe route. We

could only see a short distance ahead by reason of the great ridges and

gullies that we crossed. Below us was a steep slope, rough with

projecting crags, while, as we passed along, showers of loose stones

rolled down the mountain side and made an infernal clatter, ever

reminding us not to slip. At one o’clock we stood on the top of the

ridge 9000 feet above sea-level, having ascended 4300 feet from our last

camp.

The valley of the north

fork of the Cross River lay far below, with green timber once more in

sight, inviting us to descend. After five minutes delay, for another

photograph, we started our descent, very rapidly, at first, in order to

get warm. We descended a steep slope of ’loose debris, then through a

long gully, rather rough, and rendered dangerous by loose stones, till

at length we reached the grassy slopes, then bushes, finally trees and

forests, with a warm summery atmosphere. Here, beautiful asters and

castilleias, and beds of the fragrant Linneas, delicate, low herbs with

pale, twin flowers, each pair pendent on a single stem, gave a new

appearance to the vegetation. In still greater contrast to the dark

coniferous forests of the mountain, there were many white birch trees,

and a few small maples, the first I have ever seen in the Rockies. In a

meadow by the river we feasted on wild strawberries, which were now in

their prime.

Near the river we

discovered a trail, the first we had seen so far on our journey around

Assiniboine. After an hour of walking we came to a number of horses, and

soon saw on the other side of the river a camp of another party of

gentlemen, who were exploring this region, and had been out from Banff

twenty-four days. We forded the river, and found it a little over our

knees, but very swift.

A very pleasant half

hour was spent at this place, enjoying their hospitality, and then we

pushed on. We were now going westward up the valley, which held a

straight course of about six miles, and then turned around to the north.

The trail being good, we walked very rapidly till nightfall in a supreme

effort to reach our camp that night. Having now been on our feet almost

continuously for the past fifteen hours, we had become so fatigued that

a very slight obstruction was sufficient to cause a fall, and every few

minutes some one of the party would go headlong among the burnt timber.

We had barely enough provisions for another meal, however, and so we

desired to get as near headquarters as possible. At length, nightfall

having rendered farther progress impossible, we found a fairly level

place among the prostrate trees, and, after a meal of bacon and hard

tack, lay down on the ground around a large fire. The night was mild,

and extreme weariness gave us sound sleep. After four hours of sleep, we

were again on foot at four o’clock in the morning. We marched into camp

at 6:30, where the cooks were just building the morning fires, and

commencing to prepare breakfast.

We were without doubt

the first to accomplish the circuit of Mount Assiniboine. By pedometer,

the'distance was fifty-one miles,.which we accomplished in forty-six

hours, or less than two days.

Mount Assiniboine is

the culminating point of a nearly square system of mountains covering

about thirty-five square miles. According to my estimates from angles

taken by. surveying instruments made on the spot, the mountain is 11,680

feet in height. Later on, however, I learned from Mr. McArthur, who is

connected with the Topographical Survey, and who has probably climbed

more peaks of the Canadian Rockies than any other two men, that,

according to some angles taken on this mountain from a great distance,

the height is 11,830 feet.

Three rivers, the

Spray, the Simpson, and the North Fork of the Cross, drain this region,

and as the two latter flow into the Columbia, and the former into the

Saskatchewan, this great mountain is on the watershed, and consequently

on the boundary line between Alberta and British Columbia. About

two-thirds of the forest area round its base has been burned over, and

this renders the scenery most unattractive. The north and northwest

sides, however, are covered with green timber, and studded with lakes,

of which one is two miles or more in length. There are in all thirteen

lakes around the immediate base of the mountain, and some are

exquisitely beautiful.

The great height and

striking appearance of Mount Assiniboine will undoubtedly, in the

future, attract mountaineers to this region, especially as a much

shorter route exists than the one we followed. If the trail is opened

along the Spray River, the explorer should be able to reach the

mountain, with horses, in two days from Banff. Mount Assiniboine,

especially when seen from the north, resembles the Matterhorn in a

striking manner. Its top is often shrouded in clouds, and when the wind

is westerly, frequently displays a long cloud banner trailing out from

its eastern side. The mountain is one that will prove exceedingly

difficult to the climber. On every side the slope is no less than fifty

degrees, and on the east, approaches sixty-five or seventy. Moreover,

the horizontal strata have weathered away in such a manner as to form

vertical ledges, which completely girdle the mountain, and, from below,

appear to offer a hopeless problem. In every storm the mountain is

covered with new snow, even in summer, and this comes rushing down in

frequent avalanches, thus adding a new source of danger and perplexity

to the mountaineer.

The day of our arrival

in camp was spent in much-needed rest. Our time was now up, and it was

necessary, on the next day, to commence our homeward journey, and, as

our winding cavalcade left the beautiful site of our camp under the

towering walls of Mount Assiniboine, many were the unexpressed feelings

of regret, for in the two weeks spent here we had had many delightful

experiences, and had become familiar with every charming view of lakes

and forests and mountains.

In two days we reached

the fork where the Simpson and Vermilion rivers unite. It was our

intention to follow up the Vermilion River and reach the Bow valley by

the Vermilion Pass. The Vermilion River is at this point a large, deep

stream flowing swiftly and smoothly The valley is very wide and densely

forested, with occasional open places near the river. For three days we

progressed up the river, often being compelled to cross it on account of

the dense timber. At one place, after several of the horses had gained a

bar in the middle of the river, one of those following, got beyond his

depth and was swept rapidly down, and appeared in great danger of being

drowned. Fortunately, the animal was caught by an eddy current, and by

desperate swimming at length gained the bar. The poor beast was,

however, so much benumbed by the cold water that he could not climb upon

the bar, but the men dashed in bravely, and by pulling on head and

packs, and even his tail, the animal finally struggled into shallow

water. Standing up to our knees in the water, with a deep channel on

either side of us and an angry rapid below, our prospects were far from

encouraging.

I mounted old Chiniquy

behind Peyto and we plunged in first. “ It’s swim sure this time,” said

Peyto to me, as the water rose at once nearly to the horse’s back, and

the ice-cold water, creeping momentarily higher, gave us a most

uncomfortable sensation. The current was so swift that the water was

banked up much higher on the upstream side. Such crossings are very

exciting, for at any moment the horse may stumble on the rough bottom or

plunge into a deep hole. Chiniquy had a hard time of it and groaned at

every step, but got us across all right. The rest all followed, not,

however, over-confident at our success, to judge by their anxious looks.

All got across except one pack-horse, which, after a voyage down stream,

we finally caught and pulled ashore.

There was evidence of

much game in this valley, as we saw many tracks of deer, caribou, and

bears. One day, just as we stopped to camp, a doe started up and ran by

us. We camped on August 2nd at a beautiful spot near the summit of the

Vermilion Pass. A large stream came in from the northwest, and we set

out to explore it for a short distance, as, before leaving Banff, we had

heard of a remarkable canyon near this place.

Not more than an eighth

of a mile from the junction of the two streams the canyon commences. At

first, the stream is hemmed in by two rocky walls a few feet in height,

but as one ascends, the walls become higher and higher, and the sound of

the roaring stream is lost in the black depth of a gloomy chasm. To one

leaning over the edge of the beetling precipice, this wonderful gorge

appears like a bottomless rift or rent in the mountain side, and so deep

is it and so closely do the opposite, irregular walls press one towards

another, that it is impossible to see the waters below from which a

faint, sullen murmur comes up.

Most wonderful of all,

the canyon at length comes to a sudden termination, and here the whole

mighty stream plunges headlong, as it were, into the very bowels of the

earth. The boiling stream, turned snow-white by a short preliminary

leap, makes a final plunge downwards and is lost to sight in a dark

cavernous hole, perhaps 300 feet deep, whence proceeds a most awful

roar, like that of ponderous machinery in motion. The ground, which is

here a solid quartzite formation, fairly trembles at the terrible

concussion and force of the falling waters, while cold, mist-laden airs

ascend in whirling gusts from the awful depths. Niagara is majestically

and supremely grand, but this lesser fall, where the water plunges into

a black bottomless hole, is by far the more terrifying.

On the fourth of August

we reached the summit of the Vermilion Pass. On the summit we passed

several small lakes in the forest.

The water was of a most

beautiful color, far more vivid than any I have hitherto seen. In the

shallow places where the bottom could be easily seen, the water assumed

a bright, clear, green color, and in the deeper places, according to the

light and angle of view, the color varied to darker hues of all possible

shades and tints. The rich colors of sky and water in the Rocky

Mountains is one of the most beautiful features of the scenery, but

likewise one that can only be appreciated by actual experience.

Our horses were plagued

by great numbers of bull-dog flies as we entered the Bow valley. It

seems as though these insects were more numerous in the valley of the

Bow, and its various tributaries, than in those parts of the mountains

drained by other rivers.

At four o’clock we

reached the Bow River, and forded it where the width was about one

hundred yards, and the depth four feet. My camera and several plates

were flooded in this passage, which was, however, effected in safety.

A march of one hour

more, along the tote-road, brought us to the station of Castle Mountain,

once a thriving village in the railroad-construction days, but now

presenting a forlorn and deserted appearance. The section men flagged

the east-bound train for us, and we arrived in Banff that evening, after

having been in camp for twenty-nine days. |