|

The Waputehk

Range—Height of the Mountains— Vast Snow Fields and Glaciers—Journey up

the Bow—Home of a Prospector—Causes and Frequency of Forest Fires—A

Visit to the Lower Bow Lake—Muskegs — A Mountain Flooded with

Ice—Delightful Scenes at the Upper Bow Lake—Beauty of the Shores—Lake

Trout— The Great Bow Glacier.

THE Summit Range of the

Rocky Mountains as they extend northward from the deep and narrow valley

of the Kicking Horse River has a special name—the Waputehk

Range,—derived, it is said, from a word which in the language of the

Stoney Indians means the White Goat.

From the summit of one

of the peaks in this range, the climber beholds a sea of mountains

running in long, nearly parallel, ridges, sometimes uniting and rising

to a higher altitude, and again dividing, so as to form countless spurs

and a complicated topography. In this range each ridge usually presents

a lofty escarpment and bare precipitous walls of rock on its eastern

face, while the opposite slope is more gentle. Here the Cambrian

sandstones and shales and the limestones of later ages may be seen in

clearly marked strata tilted up, generally, toward the east, though many

of the mountains reveal contortions and faults throughout their

structure, which indicate the wellnigh inconceivable forces that have

here been at work.

The Waputehk Mountains

have remained to this day but very little known, and almost totally

unexplored, in their interior portions. No passes are known through this

range between the Kicking Horse Pass on the south and the Howse Pass on

the north. Then another long interval northwards to the Athabasca Pass

is said by the Indians to offer an impassable barrier to men and horses.

The continuity of the range is well indicated by the fact that, for a

distance of one hundred miles, these mountains present only one pass

across the range available for horses. The several ridges which form

this range rise to a very uniform altitude of 10,000 or 11,000 feet. On

Palliser’s map of this region, one peak north of the Howse Pass, Mount

Forbes, is accredited with an altitude of 13,400 feet, and the standard

atlases have for many years placed the altitude of Mount Brown at 16,000

feet, and that of Mount Hooker at 15,700 feet, but there is much reason

to doubt that any mountains attain such heights in this part of the

Rocky Mountains.

A heavy snowfall, due

to the precipitation brought about by this lofty and continuous range,

as the westerly winds ascend and pass over it, and the existence of many

elevated plateaus, or large areas having gentle slopes, have conspired

to make vast neve regions and boundless snowfields among these

mountains. From the snowfields, long tongues of ice and large glaciers

descend into the valleys, and thus drain away the surplus material from

the

higher altitudes. No

other parts of the Rocky Mountains, south of Alaska, have glaciers and

snowfields which may compare in size or extent with those of the

Waputehk Range.

The desolate though

grand extent of gray cliffs and boundless snowfields, extending farther

than the eye can reach, when seen from a high altitude, gives no

suggestion of the delightful valleys below, where many beautiful lakes

nestle among the green forests, and form picturesque mirrors for the

surrounding rugged mountains. On the shores of one of these mountain

lakes, in the genial warmth of lower altitudes, where the water is

hemmed in, and encroached upon, by the trees and luxuriant vegetation

fostered by a moist climate, the explorer beholds each mountain peak as

the central point of interest in every view. Each cliff or massive

snow-covered mountain then appears an unscalable height reaching upward

toward the heavens,—a most inspiring work of nature, raising the eyes

and the thoughts above the common level of our earth. When seen from

high altitudes, a mountain appears merely as a part of a vast panorama

or a single element in a wild, limitless scene of desolate peaks, which

raise their bare, bleak summits among the sea of mountains far up into

the cold regions of the atmosphere, where they become white with eternal

snow, and bound by rigid glaciers.

Having become much

interested in reports of the vast dimensions of the glaciers in the

Waputehk Mountains, and the beauty of the lakes, especially near the

sources of the Bow River and the Little Fork of the Saskatchewan, I

started on August 14th, 1895, with the intention of visiting those

regions and spending some time there. My outfit

consisted of five

horses, a cook, and a packer. I had engaged Peyto for the latter

service, as he had been most efficient on our trip to Mount Assiniboine.

We left Laggan a

little before noon. Not

far from the station, there commenced an old tote-road, which runs

northward for many miles toward the source of the Bow River. This

tote-road had been hastily built for wagons, previous to the

construction of the railroad through the Kicking Horse Pass, for at one

time it was thought the line would cross the range by the Howse Pass.

Thus for several miles

we enjoyed easy and rapid travelling. The weather was mild and pleasant,

and my men seemed pleased at the prospect of another month or so in

camp.

In the course of a few

miles we came to the house of an old prospector. As this was the

farthest outpost of civilization, and the old man was reported to be an

interesting character, I entered the log-house for a brief visit. The

prospector’s name was Hunter. I found him at home and was cordially

welcomed. Here, in a state of solitude and absolute loneliness, with no

lake or stream to entertain, and surrounded by a bristling maze of

bleached bare sticks looking like the masts of countless ships in a

great harbor, this man had spent several years of his life, and,

moreover, was apparently happy. On his table I saw spread about

illustrated magazines from the United States and Canada, newspapers, and

books. The house was roughly but comfortably finished inside, and

furnished with good chairs and tables evidently imported from

civilization.

This isolated dwelling

and its solitary inhabitant reminded me somewhat of Thoreau at Walden

Pond. Like this lover of nature, Hunter enjoys his hermit life, which he

varies occasionally by a visit to the village of Laggan. Hunter had the

better house of the two men, but Thoreau must have had much more to

entertain him, in his garden, and the beautiful lake with its constant

change of light and shadow, and the surrounding forests full of

well-known plants and trees, where his bird and animal friends lived in

undisturbed possession.

No sooner had we taken

leave of this interesting home of the old prospector, than the trail

plunged into the intricacies of the burnt timber, and our horses were

severely tried. Peyto and another man had been at work on this part of

the trail for two days, very fortunately for us, as without some

clearing we should not have been able to force our way through.

The fire had run

through after the tote-road was built, so that the fallen timber now

rendered it nearly impassable in many places. The forest fires have been

much more frequent since the country has been opened by the whites, but

it would be a great mistake to conclude that before the arrival of

civilized men the country was clothed by an uninterrupted primeval

forest. When we read the accounts of Alexander Mackenzie, and the

earliest explorers in the Rocky Mountains, we find burnt timber

frequently mentioned.

However, these accounts

only cover the last one hundred years, and records of geology must be

sought previous to 1793. Dr. Dawson mentions a place near the Bow River

where forest trees at least one hundred years old are growing over a bed

of charcoal made by an ancient forest fire. Another bank near the Bow

River, not far from Banff, reveals seven layers of charcoal, and under

each layer the clay is reddened or otherwise changed by the heat. Thus

the oldest records carry us back thousands of years. The cause of these

ancient fires was probably, in great part, lightning, and possibly the

escaping camp fires of an aboriginal race of men.

Forest fires in the

Canadian Rockies only prevail at one season of the year—in July, August,

and September, —when the severe heat dries up the underbrush and fallen

timber. Earlier than this, everything is saturated by the melting snows

of winter, while in autumn the sharp frosts and heavy night dews keep

the forests damp. According to the condition of the trees, a forest fire

will burn sometimes slowly and sometimes with fearful rapidity. When a

long period of dry, hot weather has prevailed, the fire, once started,

leaps from tree to tree, while the sparks soar high into the air and,

dropping farther, kindle a thousand places at once. The furious uprush

of heated air causes a strong draught, which fans the fire into a still

more intense heat. Sometimes whirlwinds of smoke and heated air are seen

above the forest fires, and at other times the great mass of vapor and

smoke rises to such a height that condensation ensues, and clouds are

formed. In the summer of 1893, a forest fire was raging about five miles

east of Laggan. Standing at an altitude of 9000 feet, I had a grand view

of the ascending smoke and vapors, which rose in the form of a great

mushroom, or at other times more like a pine tree,—in fact, resembling a

volcanic eruption. Judging by the height of Mount Temple, the clouds

rose about 13,000 feet above the valley, or to an altitude of 18,000

feet above sea-level. It was a cumulus cloud, shining brilliant in the

sunlight, but often revealing a coppery cast from the presence of smoke.

The ascending vapors gave a striking example of one of the laws of

rising air currents. The tendency of an ascending column of air is to

break up into a succession of uprushes, separated by brief intervals of

repose, and not to rise steadily and constantly. The law was clearly

illustrated by this cloud, which, at intervals of about five or six

minutes, would nearly disappear and then rapidly form again and rise to

an immense height and magnitude.

In the course of a few

years after a forest fire has swept along its destructive course, the

work of regeneration begins, and a new crop of trees appears. Sometimes

the growth is alike all over the burnt region, young trees springing up

spontaneously everywhere, and sometimes the surrounding green forests

send out skirmishers, and gradually encroach on the burnt areas.

Curiously enough, however, a new kind of tree replaces the old almost

invariably. Out on the prairie the poplar usually follows the coniferous

trees, but in the Rockies, where the poplar can not grow at high

altitudes, the pines follow after spruce and balsam, or vice versa. The

contest of species in nature is so keen that the slightest advantage

gained by any, is sufficient to cause its universal establishment. This

is probably due to the fact that the soil becomes somewhat exhausted in

the particular elements needed by one species of tree, so that when they

are removed by an unnatural cause, new kinds have the advantage in the

renewed struggle for existence. Thus we have a natural rotation of crops

illustrated in the replacement of forest trees.

While we have been

considering the causes and effects of forest fires, our horses and men

have been struggling with the more material side of the question, and as

the imagination leaps lightly over all sorts of obstacles, let us now

overtake them as they arrive at a good camping place about eight miles

from Laggan. Here the Bow is no longer worthy the name of a river, but

is rather a broad, shallow stream, flowing with moderate rapidity.

Towards evening Peyto shot a black duck on the river, and I caught a

fine string of trout, so that our camp fare was much improved.

The next day we marched

for about three hours through light forests and extensive swamps,

finally pitching our camp near the first Bow Lake. The fishing was

remarkably fine in this part of the river. From a single pool I caught,

in less than three minutes, five trout which averaged more than one

pound each. We camped in this place for two days in order to have time

to explore about the lake. This first Bow Lake is about four miles long,

by perhaps one mile wide, and occupies the gently curving basin of a

valley which here sweeps into that of the Bow. There is something

remarkable in the unusual manner in which the Bow River divides itself

into two streams some time before it reaches this lake. The lesser of

these two ' streams continues in a straight course down the valley,

while the larger deviates to the west and flows into the lower end of

the lake, only to flow out again about a fourth of a mile farther down,

at the extreme end of the lake. The island thus formed is intersected

everywhere by the ancient courses of the river, which are now marked by

crooked and devious channels, in great part filled with clear water,

forming pools everywhere. This whole region must have once formed part

of a much larger lake, as for several miles down the valley there are

extensive swamps, almost perfectly level and underlaid by large deposits

of fine clay.

The drier places in

these muskegs are covered with a growth of bushes or clumps of trees,

gathered together on hummocks slightly elevated above the general level.

A rich growth of grass and sedge covers the lower and wetter places,

which often assume all the features of a peat bog, with a thick growth

of sphagnum mosses, while the ground trembles, for many yards about,

under the tread of men and horses.

The next day Peyto and

I crossed the river on one of our best horses known as the “Bay,” and

after turning him back towards the meadow, we started on a tramp around

the lake. We followed the west shore for the entire distance. The last

half mile was over a talus slope of loose stones, broken down from the

overhanging mountain, and now disposed at a very steep angle. There was

a barely perceptible shelf or beach about six inches wide, just at the

edge of the water, which we gladly took advantage of while it lasted.

The glacial stream

entering the lake has built out a curious delta, not fan-shaped as we

should expect, but almost perfectly straight from shore to shore. This

delta is a great gravel wash, nearly level, and quite bare of trees or

plants, except a few herbs, the seeds of which have lately been washed

down from higher up the valley. All this material has been carried into

the lake since the time when, in the great Ice Age, these valleys were

flooded with glaciers several thousand feet in depth.

As we turned the corner

near the end of the gravel wash, the glaciers at the head of the valley

began to

appear, and in a few

more steps we commanded a magnificent view of a great mountain,

literally covered by a vast sheet of ice and snow, from the very summit

down to our level. As we looked up the long gentle slope of this

mountain, we could hardly realize that it rose more than 5000 feet above

us. The glacier which descended into the valley was not very wide, but

showed the lines of flow very clearly. Six converging streams of ice

united to form the glacier on our right, while the glacier on the left

poured down a steep descent from the east, and formed a beautiful ice

cascade, where the sharp-pointed seracs, leaning forward, resembled a

cataract suddenly frozen and rendered motionless. As if by way of

contrast, a beautiful little waterfall poured gracefully over a dark

precipice of rock on the opposite side of the valley, and added motion

to this grand expanse of dazzling white snow. The loud-roaring, muddy

stream near where we stood, is one of the principal sources of the Bow,

and, after depositing its milky sediment in the lake, the waters flow

out purified and crystal clear, of that deep blue color characteristic

of glacial water. On a smaller scale this lake is like Lake Geneva, with

the Rhone entering at one end, muddy and polluted with glacial clays,

and flowing out at the other, transparently clear, and blue as the skies

above it.

After a partial ascent

of Mount Hector on the next day, we moved our camp and continued our

progress up the Bow River for about two hours. Here we camped on a

terrace near the water, surrounded on all sides by a very light forest

in a charming spot. On the following day the trail led us for two miles

through some very bad country, where the horses broke through the loose

ground between the roots of trees, and in their efforts to extricate

themselves were often in great danger of breaking a leg. Fortunately,

however, this was not of long duration. The trail soon improved and

became very clearly marked like a well made bridle-path. It led us along

the banks of the Bow, through groves of black pine, with a few spruces

intermingled. The ascent was constant, though gradual, and our altitude

was made apparent by the manner in which the trees grew in clumps, and

by the fact that the forests were no longer densely luxuriant, but quite

open, so that the horses could go easily among the trees in any

direction.

In about three hours

after leaving camp, our horses entered an open meadow where the trail

deserted us, but there was not the slightest difficulty in making good

progress. To the south, a great wall of rock rose to an immense height,

one of the lower escarpments of the Waputehk Range, and as we progressed

through the pleasant' moors a remarkable glacier was gradually revealed,

clinging to the cliffs in a three-pronged mass. As, one by one, these

branches of the glaciers were disclosed, they appeared first in profile,

and owing to the very steep pitch down which the ice was forced to

'descend, the glacier was rent and splintered into deep crevasses, with

sharp pinnacles of ice between, which appeared to lean out over the

steep descent and threaten to fall at any moment.

The absence of trees to

the north of us, and the general depression of the country in that

direction, gave us every indication that we were approaching the Upper

Bow Lake, nor were our surmises incorrect, for in a few minutes more of

progress, after seeing the glacier, glimpses of water surface were to be

had in the near distance among the trees. I went ahead of our column of

horses and selected a beautiful site for our camp, on the shore of the

lake, only a few yards from the water. The surrounding region was

certainly the most charming I have seen in the Rocky Mountains. The lake

on which we camped was nearly cut off from the main body of water to the

north, by a contraction of the shores to a narrow channel. In fact, it

might be regarded as a land-locked harbor of the Upper Bow Lake. Just

below our camping place the waters were contracted again, and descended

in a shallow rapid to another lake, resting against the mountain side on

the south. This latter lake is about three or four feet lower than the

others, and appeared to -be about two-thirds of a mile in length.

This region, for the

artist with pencil and brush, would be a fairy-land of inexhaustible

treasures. The shores along these various lakes were of a most irregular

nature, and in sweeping curves or sudden turns, formed innumerable coves

and bays, no less pleasing by reason of their small extent. Long, low

stretches of land, adorned with forest trees, stretched straight and

narrow far out into the two larger lakes, their ends dissolving into

chains of wooded islands, separated from the mainland by shallow

channels of the clearest water. In every direction were charming vistas

of wooded isles and bushy shores, while in the distance were the

irregular outlines of the mountains, their images often reflected in the

surface of the water. The very nature of the shores themselves, besides

their irregular contours, varied from place to place in a remarkable

manner. In one locality the waters became suddenly deep, the abrupt

shores were rocky, and formed low cliffs; in other places the bottom

shelved off more gradually, and there would be a narrow beach of sand

and small pebbles, ofttimes strewed with the wreckage of some storm,—a

massive tree trunk washed upon the beach, or stranded in shallow water

near the shore.

There were, moreover,

many shallow areas and swampy tracts where a rich, rank growth of water

grasses and sedges extended into the lake. Such border regions between

the land and water were perhaps the most beautiful and attractive of all

the many variations of these delightful shores. The coarse, saw-edged

leaves of the sedges, harsh to the touch, are pliant in the gentlest

breath of wind. The waving meadows of green banners, or ribbons, rising

above the water, uniform in height, and sensitive to the slightest air

motion, rustle continuously as the breezes sweep over them, and rub

their rough surfaces together.

From this region,

wherein were combined so many charming views of nature, with mountain

scenery, lakes, islands, and forests, all of the most attractive kind,

it proved impossible to move our camp for several days.

During the time that we

remained here, our explorations and wanderings took us along all the

shores and islands, and up the neighboring mountain slopes. On one of

the islands opposite our camp we discovered a small pool of singular

formation. The pool was nearly circular, and about ten yards in

diameter. The bottom was funnel-shaped, and in the very centre was a

black circle—in fact a bottomless hole—apparently connected by dark

subterranean channels with the depths of the adjacent lake. Its borders

were low and swampy, where the spongy ground quaked as we moved about,

and trembled so much that we feared at any moment to be swallowed up. In

fact the whole pool became rippled by the movements of its banks.

The glacier opposite

was the object of another trip, and this, too, proved interesting. The

neve on the flat plateau above discharges its surplus ice for the most

part by hanging glaciers, which from time to time break off and fall

down the precipice. We were often startled both day and night by the

thunder of these avalanches. Two tongues of ice, however, effect a

descent of the precipice where the slope is less steep, and though much

crevassed and splintered by the rapid motion, they reach the bottom

intact. Here the two streams, together with the accumulations of ice

constantly falling down from above, become welded into a single glacier,

which terminates only a short distance from the lake. The most unusual

circumstance about this glacier is the fact that the ice is much higher

at the very end than a little farther back, so that a great, swelling

mound of ice, about 200 feet thick, forms the termination.

About one fourth of a

mile below the end of the glacier, on an old moraine ridge now covered

over with luxuriant forest, we saw a towering cliff of rock rising above

the trees. This proved, on a closer examination, to be a separate

boulder, which must have been carried there by the ice a long time ago.

It was of colossal proportions, at least sixty feet high, and nearly as

large in its other dimensions. From the top we had an extensive view of

the lakes and valleys; while at its base we found on one side an

overhanging roof, making so complete a shelter, that it was not

difficult to imagine this place to-have been used by savages, in some

past age, as a cave dwelling.

Many years ago, not

less than one hundred, the forests on the slopes to the east of the

valley had been devastated by a fire. The long lapse of time intervening

had, however, nearly obliterated the dreary effects of this destruction.

The trees had replaced themselves scatteringly among the dead timber,

and attained a large size. The fallen trunks showed the great length of

time they had lain on the ground by the spongy, decomposed condition of

the wood. Many of the trunks had dissolved into red humus, the last

stage of slowly decomposing wood, and the fragments were disposed in

lines, bare of vegetation, indicating where each tree had found its

final resting-place.

The swampy shores and

large extent of water surface in this region fostered many varieties of

gnats, mosquitoes, and other insects, though, fortunately, not in such

great numbers as to be very troublesome. In fact, the season of the year

was approaching that period when the mosquitoes suddenly and regularly

disappear, for some unexplained reason. I have always noticed that in

the Canadian Rockies the mosquitoes become much reduced in numbers

between the 15th and 20th of August, and after that time cause little or

no trouble. In order, however, that there may be no lack of insect

pests, nature has substituted several species of small flies and

midgets, which appear about this time and follow in a rotation of

species, till the sharp frosts of October put an end to all active

insect life. Some of these small pests are no less troublesome than the

mosquitoes which have preceded them, though they afford a variation in

their manner of annoyance, and are accordingly the more endurable.

Along the reedy shores

of the lake and sometimes over its placid surface, when the air was

quiet toward evening, we often saw clouds of gnats hovering motionless

in one spot, or at times moving restlessly from place to place, like

some lightless will-o’-the-wisp, composed of a myriad of black points,

darting and circling one about another. Nature seems to love circular

motion: for just as the stars composing the cloudy nebulae revolve about

their centres of gravity in infinite numbers, moving forever, through an

infinity of space; so do these ephemeral creations of our world pass

their brief lives in a ceaseless vortex of complicated circles.

On one occasion we

built a raft to ferry us across the narrow part of the lake so that we

might try the fishing on the farther side. The raft was hastily

constructed, and, after we had reached deep water, it proved to be in a

state of stable equilibrium only when the upper surface was a yard under

water. After a thorough wetting we finally reached the shore, and

proceeded to build a more trustworthy craft.

On the 21st of August

we moved our camp down to the north end of the lake. Here the nature of

the scenery is entirely changed. Whereas the lower end of the lake

abounds in land-locked channels and wooded islands, so combined as to

make the most pleasing and artistic pictures from every shore, the other

part of this lake presents regular shore lines, and everything is formed

on a more extensive scale. The north side of the lake is curved in a

great arc, so symmetrical in appearance that it seems mathematically

perfect, and the eye sweeps along several miles of shore at a single

glance as though this were some bay on the sea-coast.

As we neared the north

end of the lake, a valley was disclosed toward the west, and an immense

glacier appeared descending from the crest of the Waputehk Range. Even

at a distance of three or four miles, this glacier revealed: its great

size. The lower part descended in several regular falls to nearly the

level of the lake. In the lower part, the glacier is less than a mile in

width, but above, the ice stream expands to three or four miles, and

extends back indefinitely, probably ten miles or more.

This Great Bow Glacier

had the same position relatively to the lake, as the glacier we visited

at the Lower Bow Lake held to that body of water.

A better knowledge of

these lakes revealed a striking similarity between them. Each lake

occupies a curving valley, which in each case enters the Bow valley from

the south. The two lakes are about the same size and nearly the same

shape, a long gentle curve about five times longer than broad. At the

head of each, though at slightly different distances, are large

glaciers. The glacial streams have likewise formed flat gravel washes,

or deltas, which have encroached regularly on the lake and formed a

straight line from shore to shore, perfectly similar one to another. A

further resemblance might be observed in the presence of two talus

slopes from the mountain sides, in each case on the south side of the

lake, near the delta. The Lower Bow Lake is about 5500 feet above

sea-level, while the upper lake is a little more than 6000 feet. The

increased altitude has the effect of making the forest more open, and

the country more generally accessible, in the region of the upper lake.

From one point on the shores of the upper lake, five large glaciers may

be counted, the least of which is two miles long, and the greatest has

an unknown extent, but is certainly ten miles in length.

Our camp was pleasantly

located in the woods not far from the water. After Peyto had put up the

tent and got the camp in order, with the horses enjoying a fine pasture,

he set off to explore the lake shore toward the Great Glacier. He

returned to camp about five o’clock carrying a fine lake trout which he

had caught. This fish

was taken near the

shore, and was probably a small one compared with those which live in

deeper water; nevertheless, it measured twenty - three inches in length,

and weighed about seven

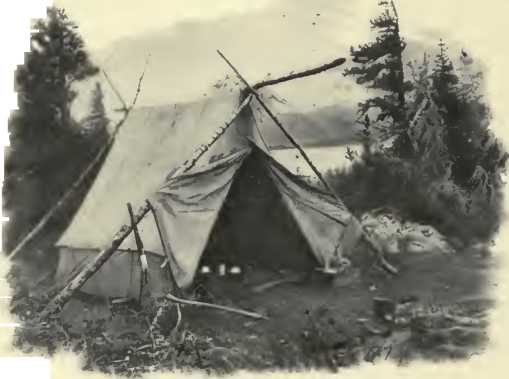

CAMP AT UPPER BOW LAKE.

pounds. The Bow lakes

have a reputation for abounding in fish of a very large size. So far as

I am aware, no boat has ever sailed these waters, and there is no

certainty what size the fish may reach in the deeper parts of the lake.

Judging by trout which have been caught in Lake Minnewanka, near Banff,

it is very probable that they run as high as thirty or forty pounds.

The next day, Peyto and

I took a lunch with us and spent the entire day exploring and

photographing the glacier and its immediate neighborhood. The ice is not

hemmed in by any terminal moraine, but shelves down gradually to a thin

edge. In fact the termination of the glacier resembles somewhat the hoof

of a horse, or rather that of a rhinoceros, the divided portions being

formed by crevasses, while long thin projections of ice spread out

between. It is a very easy matter to get on the glacier, and quite safe

to proceed a long way on its smooth surface. We had some fine glimpses

of crevasses so deep that it was impossible to see the bottom, while the

rich blue color of the ice everywhere revealed to us marvels of colored

grottoes and hollow-sounding caverns, their sides dripping with the

surface waters. There is something peculiarly attractive, perhaps from

the danger, pertaining to a deep crevasse in a glacier. One stands near

the edge and throws, or pushes, large stones into these caverns, and

listens in awe to the hollow echoes from the depths, or the muffled

splash as the missile finally reaches a pool of water at the bottom.

There is a suggestion of a lingering death, should one make a false step

and fall down these horrible crevasses, where, wedged between icy walls

far below the surface, one could see the glimmering light of day above,

while starvation and cold prolong their agonies. A party of three

mountaineers thus lost their lives on Mount Blanc in 1820, and more than

forty years later their bodies were found at the foot of the Glacier des

Bossons, whither they had been slowly transported, a distance of several

miles, by the movement of the ice. The most dangerous crevasses are not

those of the so-called “dry glacier,” where the bare ice is everywhere

visible, but those of the neve regions where the crevasses are

concealed, or obscured by the overlying snow.

Not far from the foot

of the glacier the muddy stream flows through a miniature canyon, with

walls near together, cut out of a limestone formation. The water here

rushes some quarter of a mile, foaming and angry, as it dashes over many

a fall and cascade. Where the canyon is deepest an immense block of

limestone about twenty-five feet long has fallen down, and with either

end resting on the ' canyon walls, it affords a natural bridge over the

gloomy chasm. As probably no human being had ever crossed this bridge,

we felt a slight hesitation in making the attempt, fearing that even a

slight jar might be sufficient to dislodge the great mass. It proved,

however, quite safe and will undoubtedly remain where it is for many

years and afford a safe crossing-place for those who visit this

interesting region. |