|

Sources of the Bow—The

Little Fork Pass—Magnificence of the Scenery—Mount Murchison—Camp on the

Divide—A High Mountain Ascent—Future of the Bow Lakes—Return down the

Bow—Search fora Pass—Remarkable Agility of Pack-Horses—The “ Bay" and

the “Pinto " —Mountain Solitudes—Mount Hector—Difficult Nature of

Johnston Creek—A Blinding Snow-Storm—Forty-Mile Creek—Mount Edith Pass.

A FINE trout stream

entered the lake near our camp. This was, in fact, the Bow River. It

held a meandering course a short distance before entering the lake,

through a level meadow, or rather an open region, thickly grown over

with alder bushes and other shrubby plants.

We were delayed at this

camp by a period of unsettled weather with occasional storms and strong

winds, so that three days were required to finish our explorations. At

length, on the 24th of August, we broke camp, and followed the Bow

valley northwards towards the source of the river. The valley preserves

its wide character to the head of the pass, and is unusual among all the

mountain passes for several reasons. The ascent to the summit is very

gradual and constant, the valley is wide, and the country is quite open.

In about two hours we came to the summit, and, after a long level reach,

the slope insensibly changed and the direction of drainage was reversed.

This was a most

delightful region. The smooth valley bottom sloped gradually upward

toward the mountains on the east and west, and insensibly downward

toward the valleys north and south, thus making an extensive region with

gentle slopes curving in two directions, which in some way impresses the

mind with a sense of quiet grandeur and indefinite liberty. But chiefly

this region of the divide is made charming by a most beautiful

arrangement of the trees. There are no forests here, nor do the trees

grow much in groves or clumps, but each tree stands apart, at a long

interval from every other, so that the branches spread out symmetrically

in every direction and give perfect forms and beautiful outlines.

Between are smooth meadows, quite free of brush, but crowded with

flowering plants, herbs, and grasses, so that the general impression is

that of a gentlemans park, under the control and care of a landscape

gardener, rather than of the undirected efforts of nature.

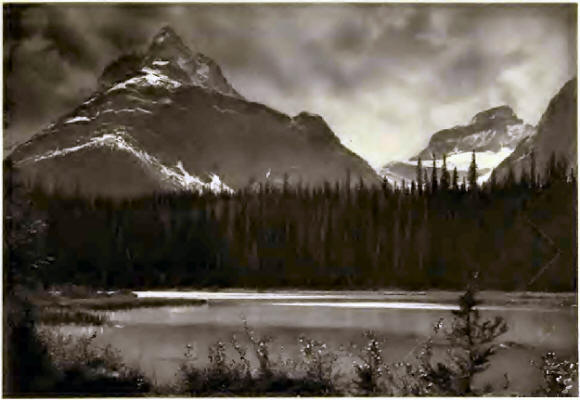

I shall never forget

the first view we had into the valley of the Saskatchewan. Approaching a

low ridge at the south side of the valley, suddenly there is revealed a

magnificent panorama of glaciers, lakes, and mountains, unparalleled

among the Canadian Rockies for its combination of grandeur and extent.

To the south,-one beholds the end of an immense glacier, at the

termination of which there are two great arched caverns in the ice. From

out these issue two roaring glacial streams, the source of the

Saskatchewan River, or at least of its longest tributary called the

Little Fork. Lofty mountains hem in this glacier on either side, only

revealing a portion of the vast neve which may be seen extending

southward for six or seven miles.

To the north and, as it

were, at our feet, though in reality a thousand feet below, lay a large

and beautiful lake with irregular outlines. This lake reaches several

miles down the valley of the Little Fork, which here extends northward

so straight and regular, that the view is only limited at the distance

of thirty miles by the long range of mountains on its east side. Dr.

Hector, who came through this region in the fall of 1858, comments on

the magnificent extent and grandeur of this view.

Through a notch in a

mass of mountains to the north, there appeared the extreme summit of

Mount Murchison, a very sharp and angular rock peak, which the Indians

regard as the highest mountain of the Canadian Rockies. According to

some rough angles taken by Dr. Hector, this mountain has an altitude of

13,500 feet. In Palliser’s Papers a sketch of- this mountain, as seen

from the summit of the Pipestone Pass, makes the rock peak much more

sharp and striking in. appearance even than that of Mount Assiniboine,

or of Mount Sir Donald in the Selkirks.

We continued our

journey over the pass and descended into the valley of the Little Fork

for several miles. The trail was very good, though the descent was

remarkably steep. We camped by a small narrow lake, in reality merely an

expansion of the Little Fork. Behind us was an area of burnt timber, but

southward the forests were in their primeval vigor and the mountains

rose to impressive heights above. The weather became rather dubious, and

during the night there was a fall of rain, followed by colder weather,

so that our tent became frozen stiff by morning.

It seemed best to

return the next day to the summit of the pass, where everything

conspired to make an ideal camping place. Accordingly, the men packed

the horses and we located our camp on the crest of the divide, 6350 feet

above sea-level. The tent was pitched in a clump of large trees

surrounded on all sides by open meadows, where one could wander for long

distances without encountering rough ground or underbrush. Near the camp

a small stream, and several pools of clear water, were all easily

accessible.

The next day I induced

Peyto to ascend a mountain with me. He was not used to mountain

climbing, and had never been any higher than the ridge that we were

compelled to cross when we were walking around Mount Assiniboine, which

was less than 9000 feet in altitude. The peak which I had now in view

lay just to the northeast from our camp on the pass. It appeared to be

between 9000 and 10,000 feet high, and offered no apparent difficulties,

on the lower part at least. We left camp at 8:30 a.m. and passed through

some groves of spruce and balsam, where we had the good fortune to see

several grouse roosting among the branches of the trees. Peyto soon

brought them down with his six-shooter, in handling which he always

displays remarkable accuracy and skill. Many a time, when on the trail,

I have seen him suddenly take his six-shooter and fire into a tall tree,

whereupon a grouse would come tumbling down, with his neck severed, or

his head knocked off by the bullet.

A hawk scented our game

and came soaring above us so that we had to hide our birds under a

covering of stones, as of course we did not care to take them with us up

the mountain. We found not the slightest difficulty in the ascent till

we came near the summit. The atmosphere was remarkably clear, and some

clouds high above the mountains rendered the conditions very good for

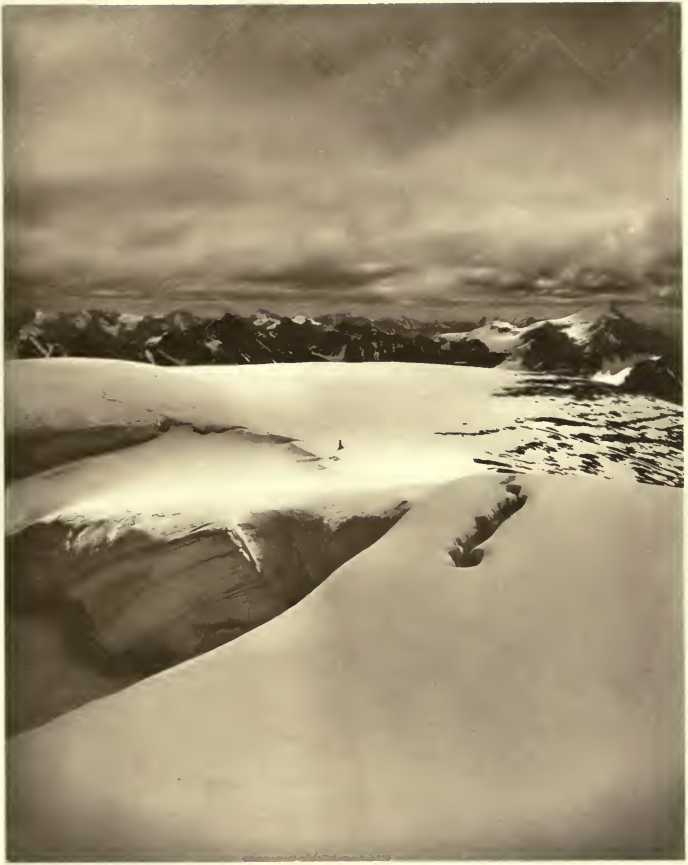

photography. At an altitude of 9800 feet we came to the summit of the

artte which we were climbing, and saw the highest point of the mountain

about one-third of a mile distant, and considerably higher. Fortunately,

a crest of snow connected the two peaks, and with my ice-axe I knocked

away the sharp edge, and made a path. In a few minutes we were across

the difficult part and found an easy slope rising gradually to the

summit. We reached it at 11130, and found the altitude 10,125 feet. The

view from the great snow dome of this unnamed mountain was truly

magnificent. The Waputehk Range could be seen through an extent of more

than seventy-five miles, while some of the most distant peaks of the

Selkirks must have been more than one hundred miles from where we stood.

To the east about ten miles was the high peak of Mount Hector, almost

touching the clouds.

In the northern part of

the Waputehk Range we saw some very high peaks, though the clouds

covered everything above 11,000 feet. There seemed to be a storm in that

direction, as snow could be discerned falling on the mountains about

thirty miles distant. The general uniformity of height, and the absence

of unusually high peaks, a characteristic feature of the Canadian

Rockies, were very clearly revealed from this mountain.

Peyto was overwhelmed

with the magnificent panorama, and said that he now appreciated, as

never before, the mania which impels men to climb mountains. The storm

which we saw in the west and north passed over us toward evening, in the

form of gentle showers. On the next day, however, the weather was

perfectly clear and calm.

On the 26th of August

our horses were packed and our little procession was in motion early in

the morning, and we were wending our way down the Bow River. I cannot

take leave of this region, however, even in imagination, without a word

in regard to the unusual attractiveness of this part of the mountains.

In the first place

there are magnificent mountains and glaciers to interest the

mountaineer, and beautiful water scenes, with endless combinations of

natural scenery for the artist; moreover, the streams abound in brook

trout* and the lakes are full of large lake trout, so numerous as to

afford endless sport for fishermen. The botanist, the geologist, and the

general lover of science will likewise find extensive fields of inquiry

open to him on every side.

The time of travelling

required by us to reach the Upper Bow Lake was about nine hours, and

this was with heavily laden pack-horses. Hitherto, only those con-nected

with the early explorations, or the railroad surveys, have visited this

lake, but I cannot look forward to the future without conjuring up a

vision of a far different condition of things. In a few years, if I

mistake not, a comfortable building, erected in a tasteful and artistic

manner, will stand near the shores of this lake on some beautiful site.

A steam launch and row-boats or canoes will convey tourists and

fishermen over the broad waters of the lake, and a fine coach road will

connect this place with Laggan, so that passengers may leave Banff in

the morning and, after a ride of two hours by railroad, they will be

transferred to a coach and reach the Upper Bow Lake in time for lunch !

If a good road were constructed this would not be impossible, as the

distance from Laggan is only about twenty miles, and the total ascent

iooo feet.

With such visions of

the future and the more vivid memory of recent experiences in mind, we

took leave of the beautiful sheet of water, and continued on our way

down the Bow valley. It was not our purpose, however, to return to

Laggan directly, for Wilson had planned an elaborate route, by which

some of the wilder parts of the mountains might be visited. This route

would lead us over a course of about eighty or one hundred miles through

the Slate Mountains and Sawback Range, and eventually bring us to Banff.

We were to follow a

certain stream that enters the Bow from the north, but as we were now,

and had been for many days, outside the region covered by Dawson’s map,

it was impossible to feel certain which stream we should take. On our

way up the Bow River, Peyto had made exploring excursions into several

tributary valleys, but in every case these had proved to be hemmed in by

precipitous mountain walls, and guarded at the ends by impassable cliffs

or large glaciers.

The second day after

leaving the lake we came to a large stream which had not been examined

hitherto. Though we were far from certain that this was the stream that

had been indicated by Wilson, it seemed best to follow up the valley and

see where we should come out. After ascending an exceedingly steep bank,

we found easy travelling in a fairly open valley. One fact made us

apprehensive that there was no pass out of the valley. There was no sign

of a trail on either side of the stream, and none of the trees were

blazed. Indian trails exist in almost every valley where an available

pass leads over the summit, and where there are no trails the

probability is that the valley is blind, or, in other words, leads into

an impassable mountain wall. The valley curved around in such a manner

that we could not tell what our prospects were, but at about two o’clock

we reached a place far above timber line,—a region of open moors,

absolutely treeless,—surrounded by bare mountains on every side.

Our tent was pitched in

a ravine near a small stream. Immediately after lunch, Peyto and I

ascended 1000 feet on a mountain north of the valley with the purpose of

discovering a pass. From this point we saw Mount Hector due south, and

the remarkable mountain named Mount Molar, nearly due east. Three

possible outlets from the valley appeared from our high elevation. Peyto

set off alone to explore a pass toward the north, in the direction of

the Pipestone Pass, while I made an examination of a notch toward the

east. Each proved impossible for horses, if not for human beings. The

third notch lay in the direction of Mount Hector, and together we set

out to examine it. A walk of about two miles across the rolling uplands

of this high region brought us to the pass. It was very steep, but an

old Indian trail proved that the pass was available for horses. The

trail appeared more like those made by the mountain goats than by human

beings, for it led up to a very rough and forbidding cliff, where loose

stones and long disuse had nearly obliterated the path. We spent some

time putting the trail in repair, by rolling down tons of loose stones,

and making everything as secure as possible.

The next morning was

threatening, and gray, watery clouds hung only a little above the summit

of the lofty pass, which was nearly 8000 feet above sea-level. I started

about an hour before the outfit, as I desired to observe the horses

climbing the trail. I felt considerable anxiety as they approached. All

my photographic plates, the result of many excursions and mountain

ascents in a region where the camera had never before been used, were

placed on one of the horses, for which purpose one of the most

sure-footed animals had been selected. In case of a false step and a

roll down the mountain side, the results of all this labor would be

lost. The horses, however, all reached the summit in safety.

These mountain

pack-horses reveal a wonderful agility and sagacity in such difficulties

as this place presented. In fact, the several animals in my pack-train

had become old friends, for they had been with me all summer. Peyto, as

packer, always rode in the saddle, for the dignity of this office never

allows a packer to walk, and besides, from their physical elevation on a

horse’s back they can better discern the trail. A venerable Indian

steed, long-legged and lean, but most useful in fording deep streams,

was Peytos saddle-horse. The bell-mare followed next, led by a

head-rope. The other horses followed in single file, and never allowed

the sound of the bell to get out of hearing. There were two horses in

the train that were endowed with an unusual amount of equine

intelligence and sagacity. The larger of the two was known as the “Bay,”

and the other was called “Pinto,” the latter being a name given to all

horses having irregu1ar white markings. These animals were well

proportioned, with thick necks and broad chests, and, though of Indian

stock, they probably had some infusion of Intelligence of Pack Horses.

Spanish blood in their veins, derived from the conquest of Mexico.

The Pinto was

remarkably quick in selecting the best routes among fallen timber, or in

avoiding hidden dangers, but the Bay was far more affectionate and fond

of human company. In camp, all the horses would frequently leave the

pasture and visit the tent, where they would stand near the fire to get

the benefit of the smoke when the flies were thick, or nose about in the

hope of getting some salt. On the trail, it was always very interesting

to watch the Bay and Pinto. They would unravel a pathway through burnt

timber in a better manner than their human leaders, and would calculate

in every case whether it were better to jump over a log or to walk

around it. But one day I was surprised to see the Bay jump over a log

which measured 3 feet 10 inches above the ground. With a heavy, rigid

pack this is more of a feat than to clear a much greater height with a

rider in the saddle. Sometimes when the trail was lost we would put the

Pinto ahead to lead us, and on several occasions he found the trail for

us.

The summit of the pass

revealed to us one of those lonely places among the high mountains where

silence appears to reign supreme. We were in an upland vale, where the

ground was smooth and rolling, and carpeted with a short growth of grass

and herbs. On either side were bare cliffs of limestone, unrelieved by

vegetation or perpetual snow. Here no birds or insects broke the silence

of the mountain solitude, no avalanche thundered among the mountains,

and even the air was calm and made no sound in the scanty herbage. All

was silent as the desert, or as the ocean in a perfect calm. The dull

tramp of our horses, and the tinkling of the bell, were the only sounds

that interrupted the death-like quiet of the place. It is said that such

places soon drive the lost traveller to insanity, but in company with

others these lonely passes afford a delightful contrast to the life and

motion and sound of lower altitudes.

As we advanced and

commenced to descend, the north side of Mount Hector began to appear. It

was completely covered with a great ice sheet and snow fields. Mount

Hector is a little more than 11,000 feet in altitude, and gives a good

example of how the exposure to the sun affects the size of glaciers in

these mountains. On the south and west sides of Mount Hector there is

almost no snow, while the opposite slopes are flooded by a broad glacier

many miles in area, and brilliant in a covering of perpetual snow.

At the tree line a

trail appeared, and led us in rapid * descent to the valley. The scenery

on all sides was magnificent. Many waterfalls came dashing down from the

melting glaciers of Mount Hector and joined a torrent in the valley

bottom. The great cliffs about us, and the lofty mountains, visible here

and there through avenues in the giant forest trees, were illumined by a

brilliant sun, ever now and again breaking through the clouds. About

eleven o’clock we stopped to have a light lunch, as was our custom on

all long marches. Peyto loosed the girdle of the horses, slipped off the

packs, and turned the animals into a meadow near by. Meanwhile our cook

cut firewood and made a large pot of tea, which always proved the most

acceptable drink when a long march had made us somewhat weary. These

brief rests of about forty minutes in the midst of a day’s march always

proved very beneficial to men and horses.

A long straight valley

led us southwards for many miles. In every clear pool or stream, trout

could be seen darting about and seeking hiding-places, though we had no

time to stop and catch them. At about one o’clock we reached the

Pipestone Creek and obtained a view of Mount Temple and other familiar

peaks about fifteen miles to the south.

We camped near the

stream in a meadow, not far from the Little Pipestone Creek. As the

march of this day had brought us back to the region covered by the map,

we had little apprehension of losing our way in the future.

The next day we

followed up the Little Pipestone . Creek and enjoyed a fine trail

through a dense forest. We camped near the summit of a pass south of

Mount Macoun, which I partially ascended after lunch. The rugged peak

named Mount Douglas lay due east, and presented some very large and fine

glaciers.

Our camp was on a

little peninsula jutting out into a lake, with water of a most brilliant

blue color. The sunset colors this evening were heightened by the

presence of a little smoke in the atmosphere, which gave a deep copper

color to the western sky, while the placid lake appeared vividly blue in

the evening light.

The following day,

which was the first of September, we continued south over a divide and

into the valley of Baker Creek, which we followed for several hours, and

then took a branch stream which comes in from the east, and finally

camped in a high valley. We were now in the Sawback Range, where the

mountains are peculiarly rugged, and the strata thrown up at high

angles. The weather was giving evidence of an approaching storm, and

before we had made camp the next day in Johnston’s Creek, rain began to

fall.

Hitherto the nature of

the country since leaving the Upper Bow Lake had been such as to render

the travelling very easy and delightful, but from this point on, we met

with all sorts of difficulties. In the lower part of Johnston’s Creek,

and in the valley of a tributary which comes in from the northeast, the

trail was covered by fallen timber, and our progress was very slow and

tedious. Moreover, the weather now became very bad, and we were caught

near the summit of a pass between Baker Creek and Forty-Mile Creek in a

heavy snow-storm, so that the trail was soon obliterated and the

surrounding mountains could not be seen. Fearing that we might lose our

bearings altogether, Peyto urged forward the horses at a gallop, so that

we might get over the pass before the snow gained much depth.

The descent into the

valley of Forty-Mile Creek was very steep, and we camped among some

large trees with several inches of snow on the ground. The next day we

urged our horses on again and followed down the valley of Forty-Mile

Creek. In some parts of the valley we found absolutely the worst

travelling I have anywhere met with in the Rockies. The horses were

compelled to make long detours among the dead timber, and the axe was

frequently required to cut out a passage-way. Frequent snow showers

swept through the valley, and, though very beautiful to look at, they

kept the underbrush covered with damp snow and saturated our clothes

with water.

In the afternoon we

reached the summit of the Mount Edith Pass, and once more caught- sight

of the Bow valley and the flat meadows near Banff. A fine wide trail or

bridle-path, smooth and hard, led us down toward the valley. The

contrast to our recent trails was very striking. We walked between a

broad avenue of trees, each one blazed to such an extent that all the

bark had been removed on one side of the tree, and some were practically

girdled. This was very different from our recent experience where we had

only found a small insignificant axe-mark on some dead tree, about once

in every quarter mile, or often none at all during hours of progress.

On the fifth of

September we reached Banff late in the evening, and found that the

valley was free of new snow by reason of its lower altitude. We had been

out for twenty-three days and had covered, in all, about one hundred and

seventy-five miles. |