|

Captain Cook's

Explorations—The American Fur Company—First Exploration of the Fraser

River—Expedition of Ross Cox—Cannibalism —Simplicity of a Voyageur—Sir

George Simpson's Journey—Discovery of Gold in 1858—The Palliser

Expedition—Dr. Hectors Adventures— Milton and Cheadle—Growth of the

Dominion—Railroad Surveys— Construction of the Railroad—Historical

Periods—Future Popularity />f the Canadian Rockies.

THE early explorations

of Captain Cook had an almost immediate effect on the development of the

fur trade. Upon the publication of that wonderful book, Cook's Voyages

rottnd the World, wherein were shown the great value and quantity of

furs obtainable along the northwest coast of America, a considerable

number of ships were fitted out for the purpose of carrying on this

trade. Three years after, or in 1792, there were twenty American vessels

along the Pacific Coast, from California northward to Alaska, collecting

furs, especially that of the sea otter, from the natives.

Of these “canoes, large

as islands, and filled with white men,” Mackenzie had heard many times

from the natives met with on his overland journey across the Rocky

Mountains. Mackenzie’s journal was not published till 1801.

In this book, however,

he outlines a plan to perfect a well regulated trade by means of an

overland route, with posts at intervals along the line, and a well

established terminus on the Pacific Coast. Should this plan be carried

out, he predicted that the Canadians would obtain control of the fur

trade of the entire northern part of North America, and that the

Americans would be compelled to relinquish their irregular trade.

While the agents of the

American Fur Company, a rival organization controlled and managed by Mr.

John Jacob Astor, were preparing to extend their limits northwards from

their headquarters at the mouth of the Columbia, the Northwest Company

was pushing southward through British Columbia, and had already

established a colony called New Caledonia near the headquarters of the

Fraser River. Thus Mr. Astor’s scheme of gaining control of the head

waters of the Columbia River was anticipated. The war of 1812 completely

frustrated his plans, when the post of Astoria fell temporarily into the

hands of the English.

A very good idea of the

hardships of life at one of these western posts, together with a brief

account of the first exploration of the Fraser River, may be obtained

from a letter written in 1809 by Jules Quesnel to a friend in Montreal.

The letter is dated New Caledonia, May 1st, 1809, and after a few

remarks on other matters, Mr. Quesnel goes on to say: “There are places

in the north where, notwithstanding the disadvantages of the country in

general, it is possible sometimes to enjoy one’s self; but here nothing

is to be found but hardship and loneliness. Far away from every one, we

do not have the pleasure of getting news from the other places. We live

entirely upon salmon dried in the sun by the Indians, who also use the

same food, for there are no animals, and we would often be without shoes

did we not procure leather from the Peace River.

“I must now tell you

that I went exploring this summer with Messrs. Simon Fraser and John

Stuart, whom you have met, I believe. We were accompanied by twelve men,

and with three canoes went down the river, that until now was thought to

be the Columbia. Soon finding the river unnavigable, we left our canoes

and continued on foot through awful mountains, which we never could have

passed had we not been helped by the Indians, who received us well.

After having passed all those bad places, not without much hardship, as

you may imagine, we found the river once more navigable, and got into

wooden canoes and continued our journey more comfortably as far as the

mouth of this river in the Pacific Ocean. Once there, as we prepared to

go farther, the Indians of that place, who were numerous, opposed our

passage, and we were very fortunate in being able to withdraw without

being in the necessity of killing or being killed. We were well received

by all the other Indians on our way back, and we all reached our New

Caledonia in good health. The mouth of this river is in latitude 490,

nearly 30 north of the real Columbia. This trip procured no advantage to

the company, and will never be of any, as the river is not navigable.

But our aim in making the trip was attained, so that we cannot blame

ourselves in any manner.”

This letter throws some

light on the history of this period, and shows whence the names of

certain rivers and lakes of British Columbia were derived. It would be

in place here to say that when Mackenzie first came to the Fraser River,

after crossing the watershed from the Peace River, he entertained the

idea that he was on the Columbia.

A few years later, the

agents of the fur companies had established certain routes and passages

across the mountains, which they were accustomed to follow more or less

regularly in their annual or semi-annual journeys. One of the largest of

these early parties to traverse the Rockies was under the management of

Mr. Ross Cox, who was returning from Astoria in the year 1817. There

were, in all, eighty-six persons in his party, representing many

nationalities outside of the various Indians and some Sandwich

Islanders.

A striking incident in

connection with this expedition illustrates the hazard and danger which

at all times attended these journeys through the wilderness. The party

had pursued their way up the Columbia River, and were now on the point

of leaving their canoes and proceeding on foot up the course of the

Canoe River, a stream that flows southward and enters the Columbia not

far from the Athabasca Pass. The indescribable toil of their passage up

the Columbia, and the many laborious portages, had sapped the strength

of the men and rendered some of them wellnigh helpless. Under these

circumstances, it seemed best that some of the weakest should not

attempt to pursue their journey farther, but should return down the

Columbia. There were seven in this party, of whom only two were able to

work, but it was hoped that the favorable current would carry them

rapidly towards Spokane, where there was a post established. An air of

foreboding and melancholy settled upon some of those who were about to

depart, and some prophesied that they "would never again see Canada, a

prediction that proved only too true. In Ross Cox’s Adventures on the

Columbia River the record of their disastrous return is thus vividly

related:

“On leaving the Rocky

Mountains, they drove rapidly down the current until they arrived at the

Upper Dalles, or narrows, where they were obliged to disembark. A

cod-line was made fast to the stern of the canoe, while two men with

poles preceded it along the banks to keep it from striking against the

rocks. It had not descended more than half the distance, when it was

caught in a strong whirlpool, and the line snapped. The canoe for a

moment disappeared in the vortex, on emerging from which it was carried

by the irresistible force of the current to the opposite side, and

dashed to pieces against the rocks. They had not had the prudence to

take out either their blankets or a small quantity of' provisions, which

were, of course, all lost. Here, then, the poor fellows found

themselves, deprived of all the necessaries of life, and at a period of

the year in which it was impossible to procure any wild fruit or roots.

To return to the mountains was impossible, and their only chance of

preservation was to proceed downwards, and to keep as near the banks of

the river as circumstances would permit. The continual rising of the

water had completely inundated the beach, in consequence of which they

were compelled to force their way through an almost impervious forest,

the ground of which was covered with a strong growth of prickly

underwood. Their only nourishment was water, owing to which, and their

weakness from fatigue and ill-health, their progress was necessarily

slow. On the third day poor Ma^n died, and his surviving comrades,

though unconscious how soon they might be called to follow him,

determined to keep off the fatal moment as long as possible. They

therefore divided his remains in equal parts between them, on which they

subsisted for some days. From the swollen state of their feet their

daily progress did not exceed two or three miles. Holmes, the tailor,

shortly followed Ma9on, and they continued for some time longer to

sustain life on his emaciated body. It would be a painful repetition to

detail the individual death of each man. Suffice it to say that, in a

little time, of the seven men, two only, named La Pierre and Dubois,

remained alive. La Pierre was subsequently found on the borders of the

upper lake of the Columbia by two Indians who were coasting it in a

canoe. They took him on board, and brought him to the Kettle Falls,

whence he was conducted to Spokane House.”

“He stated that after

the death of the fifth man of the party, Dubois and he continued for

some days at the spot where he had ended his sufferings, and, on

quitting it, they loaded themselves with as much of his flesh as they

could carry; that with this they succeeded in reaching the upper lake,

round the shores of which they wandered for some time in vain, in search

of Indians; that their horrid food at length became exhausted, and they

were again reduced to the prospect of starvation ; that on the second

night after their last meal, he (La Pierre) observed something

suspicious in the conduct of Dubois, which induced him to be on his

guard ; and that shortly after they had lain down for the night, and

while he feigned sleep, he observed Dubois cautiously opening his clasp

knife, with which he sprang on him, and inflicted on his hand the blow

that was evidently intended for his neck. A silent and desperate

conflict followed, in which, after severe struggling, La Pierre

succeeded in wresting the knife from his antagonist, and, having no

other resource left, he was obliged in self-defence to cut Dubois’s

throat; and that a few days afterwards he was discovered by the Indians

as before mentioned. Thus far nothing at first appeared to impugn the

veracity of his statement; but some other natives subsequently found the

remains of two of the party near those of Dubois, mangled in such a

manner as to induce them to think that they had been murdered; and as La

Pierre’s story was by no means consistent in many of its details, the

proprietors judged it advisable to transmit him to Canada for trial.

Only one Indian attended; but as the testimony against him was merely

circumstantial, and was unsupported by corroborating evidence, he was

acquitted.”

Meanwhile the greater

part of this expedition continued their way through the mountains by the

Athabasca Pass. Here, when surrounded by all the glory and grandeur of

lofty mountains clad in eternal snow and icy glaciers, and amid the

frequent crash and roar of descending avalanches, one of the voyageurs

exclaimed, after a long period of silent wonder and admiration—“I'll

take my oath, my dear friends, that God Almighty never made such a

place.”

On the summit of the

Athabasca Pass they were on the Atlantic side of the watershed, and here

let us take leave of them while they pursue their toilsome journey

across the great plains of Canada to the eastern side of the continent.

All of these early

expeditions were undertaken in the interests of the fur trade, and

carried out by the agents of the various fur companies, except for

occasional bands of emigrants on their way to the Pacific Coast, the

accounts of whose journeys are only referred to by later writers in a

vague and uncertain manner.

The expedition in 1841

of Sir George Simpson, however, to which reference has been made in a

previous chapter, is in many respects different from all the others. The

rapidity of his movements, the great number of his horses, and the ease

and even luxury of his camp life indicate the tourist and traveller,

rather than the scientist, the hardy explorer, or the daring seeker

after wealth in the wilderness. His narrative is the first published

account of the travels of any white man in that part of the mountains

now traversed by the Canadian Pacific Road, though he mentions a party

of emigrants which immediately preceded him in this part of his journey.

The rapidity with which Sir George Simpson was wont to travel may be

appreciated from the fact that he crossed the entire continent of North

America in its widest part, over a route five thousand miles in length,

in twelve weeks of actual travelling. The great central plains were

crossed with carts, and the mountainous parts of the country with horses

and pack-trains.

In 1858, gold was

discovered on the upper waters of the Fraser River, and a great horde of

prospectors and miners, together with the accompanying hangers-on,

including all manner of desperate characters, came rushing toward the

gold-fields, from various parts of Canada and the United States. This

year may be considered as marking the birth of a new enterprise and the

comparative decline of the fur trade ever after.

About this time, or,

more precisely, in 1857, Her Majesty’s Government set an expedition on

foot, the object of which was to examine the route of travel between

eastern and western Canada, and to find out if this route could be

shortened, or in any other manner improved upon. Moreover, the

expedition was to investigate the large belt of country, hitherto

practically unknown, which lies east of the Rocky Mountains and between

the United States boundary and the North Saskatchewan River. The third

object of this expedition was to find a pass, or passes, available for

horses across the Rocky Mountains south of the Athabasca Pass, but still

in British territory.

As this was an

excellent opportunity for the advancement of science without involving

great additional expense, four scientists, Lieut. Blackiston, Dr.

Hector, Mr. Sullivan, and M. Bourgeau, were attached to the expedition.

The party were under the control and management of Captain John

Palliser. .

The third object of

this expedition is the only one that concerns the history of

explorations in the Canadian Rockies. In their search for passes,

Captain Palliser and Dr. Hector met with many interesting adventures, of

which it is, of course, impossible to give more than the merest outline,

as the detailed account of their journeys fills several large volumes.

In August, 1858, Captain Palliser entered the mountains by following the

Bow River, or south branch of the Saskatchewan. He then followed a river

which comes in from the south, and which he named the Kananaskis, after

an Indian, concerning whom there is a legend of his wonderful recovery

from the blow of an axe, which merely stunned instead of killing him

outright.

When they approached

the summit of the pass, a lake about four miles long was discovered,

round the borders of which they had the utmost difficulty in pursuing

their way on account of the burnt timber, in which the horses floundered

about desperately. One of the animals, wiser than his generation,

plunged into the lake before he could be caught and proceeded to swim

across. Unfortunately this animal was packed with their only luxuries,

their tea, sugar, and blankets.

On the very summit of

the pass is a small lake some half an acre in extent, which overflows

toward the Pacific, and such was the disposition of the drainage at this

point that while their tea-kettle was supplied from the lake, their elk

meat was boiling in water from the sources of the Saskatchewan.

A few days later,

Captain Palliser made a lone mountain ascent near one of the Columbia

lakes, but was caught by night in a fearful thunder-storm so that he

could not reach camp till next day. His descent through the forests was

aided by the frequent and brilliant flashes of lightning.

A little later they met

with a large band of Kootanie Indians, who, though very destitute and

miserable in every other way, were very rich in horses. Captain Palliser

exchanged his jaded nags for others in better condition, and despairing

of pursuing his way farther, as the Indians were at war and would not

act as guides, he started, on the first of September, to return across

the mountains, and reached Edmonton in three weeks.

In the meantime Dr.

Hector made a branch expedition which has some incidents of interest in

connection with it. He was accompanied at first by the indefatigable

botanist, M. Bourgeau, and by three Red River men, besides a Stoney

Indian, who acted as guide and hunter for the party. Eight horses

sufficed to carry their instruments and necessary baggage, as it was not

considered necessary to take much provision in those parts of the

mountains which he intended to visit.

Some reference has

already been made to Dr. Hector’s experiences in the vicinity of Banff,

and we shall only give one or two of the more interesting details of his

later travels. He left the Bow River at the Little Vermilion Creek, and

followed this stream over the Vermilion Pass. The name of this pass is

derived from the Vermilion Plain, a place where the ferruginous shales

have washed down and formed a yellow ochre. This material the Indians

subject to fire, and thus convert it into a red pigment, or vermilion.

Perhaps the most

interesting detail of Dr. Hector’s trip is that which occurred on the

Beaverfoot River, at its junction with the Kicking Horse River. The

party had reached the place by following down the Vermilion River till

it joins the Kootanie, thence up the Kootanie to its source, and down

the Beaverfoot. Here, at a place about three miles from where the little

railroad station known as Leanchoil now stands, Dr. Hector met with an

accident which gave the name to the Kicking Horse River and Pass. A few

yards below the place, where the Beaverfoot River joins the Kicking

Horse, there is a fine waterfall about forty feet high, and just above

this, one of Hector’s horses plunged into the stream to escape the

fallen timber. They had great difficulty in getting the animal out of

the water, as the banks were very steep. Meanwhile, Hector’s own horse

strayed off, .and in attempting to catch it the horse kicked him in the

chest, fortunately when so near that he did not receive the full force

of the blow. Nevertheless, the kick knocked Hector down and rendered him

senseless for some time.

This was the more

unfortunate, as they were out of food, and had seen no sign of game in

the vicinity. His men ever after called the river the Kicking Horse, a

name that has remained to this day despite its lack of euphony.

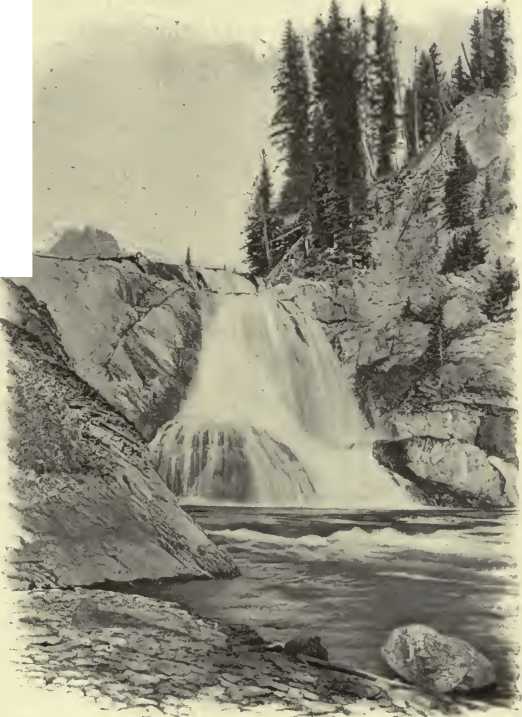

FALLS OF LEANCHOR.

one of the most

beautiful and inspiring points along the entire railroad is the descent

of the Kicking Horse Pass from the station of Hector to Field. Here, in

a distance of eight miles, the track descends iooo feet, in many a curve

and changing grade, surrounded by the towering cliffs of Mount Stephen

and Cathedral Peak, while the rich forests of the valley far below are

most beautiful in swelling slopes of dark green. Certainly, whoever has

ridden down this long descent at breakneck speed, on a small hand-car,

or railway velocipede, while the alternating rock cuts, high

embankments, and trestles or bridges of dizzy height fly by in rapid

succession, must feel at the same time a grand conception of the glories

of nature and the triumphs of man. In striking contrast to this luxury

of transportation was the old-time method of travelling through these

mountains. The roaring stream which the railroad follows and tries in

vain to descend in equally rapid slope is now one of the most attractive

features of the scenery of the pass.

When Dr. Hector first

came through this pass he had an adventure with one of his horses on

this stream. They were climbing up the rocky banks of the torrent when

the incident occurred. The horses had much difficulty in getting up, and

in Hector’s own words, “One, an old gray, that was always more clumsy

than the others, lost his balance in passing along a ledge, which

overhung a precipitous slope about 150 feet in height, and down he went,

luckily catching sometimes on the trees; at last he came to a temporary

pause by falling right on his back, the pack acting as a fender.

However, in his endeavors to get up, he started down hill again, and at

last slid on a dead tree that stuck out at right angles to the slope,

balancing himself with his legs dangling on either side of the trunk of

the tree in a most comical manner. It was only by making a round of a

mile that we succeeded in getting him back, all battered and bruised, to

the rest of the horses.”

That night they camped

at one of the lakes on the summit of the pass, but were wellnigh

famished. A single grouse boiled with some ends of candles, and odd bits

of grease, served as a supper to the five hungry men.

The next day they

proceeded down the east slope and came to a river that the Indian

recognized as the Bow. About mid-day the Stoney Indian had the good

fortune to shoot a moose, the only thing that saved the life of the old

gray that had fallen down the rocky banks of the Kicking Horse River,

for he was appointed to die, and serve as food if no game were killed

that day.

Here we shall take

leave of Dr. Hector and the Palliser expedition, and only briefly say

that Hector followed the Bow to its source and thence down the Little

Fork to the Saskatchewan and so out of the mountains. The next year Dr.

Hector again followed up the Bow River and Pipestone River to the

Saskatchewan, and thence over the Howse Pass to the Columbia, where he

found it impossible to travel either west or northwest, and was forced

to proceed southward to the boundary.

The main objects of the

Palliser expedition were in a great measure accomplished, though the

Selkirk Range of mountains was not penetrated by them, and no passes

discovered through this formidable barrier. The vast amount of useful

scientific material collected by the members of this expedition was

published in London by the British Government, but it is now,

unfortunately, so rare as to be practically inaccessible to the general

reader.

The account of an

expedition across the Rockies in 1862, by Viscount Milton and Dr.

Cheadle, is perhaps the most interesting yet published. It abounds in

thrilling details of unusual adventures, and no one who has read The

Northwest Passage by Land will ever forget the discovery of the headless

Indian when they were on the point of starvation in the valley of the

North Thompson, or the various interesting details of their perseverance

and final escape where others had perished most miserably. The object of

this expedition was to discover the most direct route through British

territory to the gold mines of the Caribou region, and to explore the

unknown regions in the vicinity of the north branch of the Thompson

River.

A period of very rapid

growth in the Dominion of Canada now follows close upon the date of this

expedition. In 1867, the colony of Canada, together with New Brunswick

and Nova Scotia, united to form the new Dominion of Canada, and, in

1869, the Hudson Bay Company sold out its rights to the central and

northwestern parts of British North America.

In the meantime the

people of the United States had been vigorously carrying on surveys, and

preparing to build railroads across her vast domains, where lofty

mountain passes and barren wastes of desert land intervened between her

rich and populous East and the thriving and energetic West, but in

Canada no line as yet connected the provinces of the central plains with

her eastern possessions, while British Columbia occupied a position of

isolation beyond the great barriers of the Rocky Mountains.

On the 20th of July,

1871, British Columbia entered the Dominion of Canada, and on the same

day the survey parties for a transcontinental railroad started their

work. One of the conditions on which British Columbia entered the

Dominion was, that a railroad to connect her with the east should be

constructed within ten years.

More than three and one

half millions of dollars were expended in these preliminary surveys, and

eleven different lines were surveyed across the mountains before the one

finally used was selected. Nor was this vast amount of work accomplished

without toil and danger. Many lives were lost in the course of these

surveys, by forest fires, drowning, and the various accidents in

connection with their hazardous work. Ofttimes in the gloomy gorges and

canyons, especially in the Coast Range, where the rivers flow in deep

channels hemmed in and imprisoned by precipitous walls of rock, the

surveyors were compelled to cross awful chasms by means of fallen trees,

or, by drilling holes and inserting bolts in the cliffs, to cling to the

rocks far above boiling cauldrons and seething rapids, where a fall

meant certain death. The ceaseless exertion and frequent exposure on the

part of the surveyors were often unrewarded by the discovery of

favorable routes, or passes through the mountains. The Selkirk Range

proved especially formidable, and only after two years of privation and

suffering did the engineer Rogers discover, in 1883, the deep and narrow

pass which now bears his name, and by which the railway seeks a route

across the crest of this range, at the bottom of a valley more than a

mile in depth.

The romance of an eagle

leading to the discovery of a pass is connected with a much earlier

date. Mr. Moberly was in search of a pass through the Gold Range west of

the Selkirks, and one day he observed an eagle flying up a narrow valley

into the heart of these unknown mountains. He followed the direction of

the eagle, and, as though led on by some divine omen, he discovered the

only route through this range, and, in perpetuation of this incident,

the name Eagle Pass has been retained ever since.

But all these surveys

were merely preliminary to the vast undertaking of constructing a

railroad. At first, the efforts of the government were rewarded with

only partial success, and at length, in 1880, the control and management

of railroad construction was given over to an organization of private

individuals. In the mountain region there were many apparently

insuperable obstacles, to overcome which there were repeated calls for

further financial aid. However, under the able and efficient control of

Sir William Van Horne, the various physical difficulties were, one by

one, overcome, while his indomitable courage and remarkable energy

inspired confidence in those who were backing the undertaking

financially. Moreover, he had a thorough knowledge of railroad

construction, together with unusual perseverance and resolution,

combined with physical powers which enabled him to withstand the nervous

strain and worry of this gigantic enterprise.

In short, after a total

expenditure of one hundred and forty million dollars, the Canadian

Pacific Railroad, which is acknowledged to be one of the greatest

engineering feats the world has ever seen, was completed, five years

before the stipulated time.

With the opening of the

railroad came the tourists and mountaineers, and the commencement of a

new period in the history of the Canadian Rockies.

The short period of one

hundred years which nearly covers the entire history of the Canadian

Rockies may be divided into four divisions. The first is the period of

the fur trade, which may be regarded as beginning with the explorations

of Sir Alexander Mackenzie in 1793, and lasting till 1857.

From 1858 to 1871 might

be called the gold period, for at this time gold-washing and the

activity consequent upon this new industry were paramount.

The next interval of

fifteen years might be called the period of railroad surveys and

construction,—a time of remarkable activity and progress,—and which

rationally closes in 1886, when the first trains began to move across

the continent on the new line.

The last period is that

of the tourists, and though as yet it is the shortest of all, it is

destined without doubt to be longer than any.

Every one of

these-periods may be said to have had a certain effect on the growth and

advance of this region. The first period resulted in a greater knowledge

of the country, and the opening up of lines of travel, together with the

establishment of trading posts at certain points.

The second period

brought about the construction of wagon roads in the Fraser Canyon

leading to the Caribou mining region and to other parts of British

Columbia. These roads were the only routes by which supplies and

provisions could be carried to the mining camps. The method of gold

mining practised in British Columbia has hitherto been mostly placer

mining, or mere washing of the gravels found in gold-bearing stream

beds.

With the commencement

of the railroad surveys, a great deal of geographical information was

obtained in regard to the several ranges of the Rocky Mountain system,

and the culmination of this period was the final establishment of a new

route across the continent, and the opening up of a vast region to the

access of travellers.

Year by year there are

increasing numbers of sportsmen and lovers of wild mountain life who

make camping expeditions from various points on the railroad, back into

the mountains, where they may wander in unexplored regions, and search

for game or rare bits of scenery.

The future popularity

of these mountains is in some degree indicated by the fact that those

who have once tried even a brief period of camp life among them almost

invariably return, year after year, to renew their experiences. The time

will eventually come when the number of tourists. will warrant the

support of a class of guides, who will conduct mountaineers and

sportsmen to points of interest in the wilder parts of the mountains,

while well made roads will increase the comfort and rapidity of travel

through the forests. |