|

The railroad terminates at the crest of a stiff incline a

mile short of the head-waters of Crooked Lake. The rural train, which

travels the roughly-laid single line on alternate days, completes the

monotonous, uneven journey with a final struggle up-grade, between lines

of coniferous forest, and comes to a cautious standstill, emitting

deep-throated blasts of rebellious protest, in a narrow clearing at the

lower edge of the small frontier town of Big River. Straggling,

train-tired passengers are told gruffly that this is the End of the

Line.

One enters the settlement—that is, one descends from the

train and traverses the total two hundred yards of main thoroughfare—and

at once, and thereafter is struck by the conflicting types of men and

habitations.

Here civilisation ends and the wilds begin. So far has

engineering and enterprise progressed; thenceforward lie the untouched

lands of the limitless North. Here commingle the old spirit of the

untamed wild and the new spirit of civilisation. There are grim men from

the woods and the trail, English-speaking, French, Galicians, Halfbreeds,

Indians, rough-clad, stalwart, untrammelled, who talk in slow-spoken

speech with fearless bearing, while about their feet move their company

of dogs—restless, prowling, hungry brutes; neglected summer pensioners,

but, in winter, the pride of their masters—the indomitable sled-dog.

They are men and beast of their surroundings; hard-fighters who wrest a

stern living from virgin forest and stream, and who ask no greater

reward than to retain their boundless freedom.

To the men their freedom is their all. They cannot tell

you why, again and again they seek the North; yet they cannot leave it.

A mood of discontent, or a vivid picture of everlasting pleasure which

they paint in imagination, sends most of them, at some time or other, to

seek “civilisation,” saying, “I will live as other people do.” But they

seldom, if ever, keep their resolve. They are out on the North trail

just as soon as the primitive wildness, which is in them as it is_ in

wild animals, awakes anew and bids them seek again the quiet places.

Such men are the vanguard—the unstarred leaders of advancing immigration

that, as the rising tide on the seashore, ever overlaps the old mark,

and escapes onward, ever onward, to populate the surface of a vast new

country.

Less prominent, far less striking, in this village of the

parting of the ways, are the people of the New World—mill clerks, and

trading storekeepers, and their assistants; and their two-score wives

and daughters. All somewhat diminutive against the strong contrast of

frontier manhood ; somewhat unworthy—even trivial. Each holding dearly

to business, to the guiling dress of the shop counter, and the much

frayed ribbons of a gaudy, doubtful society.

These are the interlopers, the people from the South; the

harbingers of civilisation, who have come, with their dollars and their

trash, to disturb the beauty and peace of virgin nature. And those are

the people who speak, with pride, of the Town-site ; who proclaim the

magnificence of a meagre street or two, of meretricious frame-built

houses in narrow land plots; and who point to the importance of a lumber

mill and a gaunt, top-heavy Boarding House as if, on that guarantee, the

future of Big River were assured, and their fortunes.

They forget too easily, in their vanity, that it is not

to those things that they owe their prosperity, but to the wonderful

richness of the nature around them. And theirs is a circumstance that

always fills me with a certain amount of sadness. They may be rich in a

worldly way, but how poor they are of intellectual enthusiasm—at their

feet lies the broad, beautiful world, yet must they trample it under

with eyes only for the god of Gold, and Power, and Pleasure. . . . Ah!

well— it is their life ; small perhaps, perhaps somewhat narrow, but'

they know no other. They are part of the great scheme of things ;

impelled by heritage and circumstance to follow a well-trodden channel,

and counselled by a strong commercial instinct to launch out into

activity and endeavour, though, in life’s short pilgrimage, they may

destroy the rich growth of centuries in building up the ardent ambitions

of the hour.

But the greater things, the things which are neither

little nor personal to any man, the phantom forces which are behind the

Universe— the forces which ordain .mankind to life, to an existence, and

to death—as fish, or fowl, or fiy, is ordered—those are the forces which

are the soul of the North. And it is a soul which whispers that the land

and water and sky of nature’s universe will grow and nourish and still

be beautiful while race after race of mankind rise up, halt a little,

and pass away.

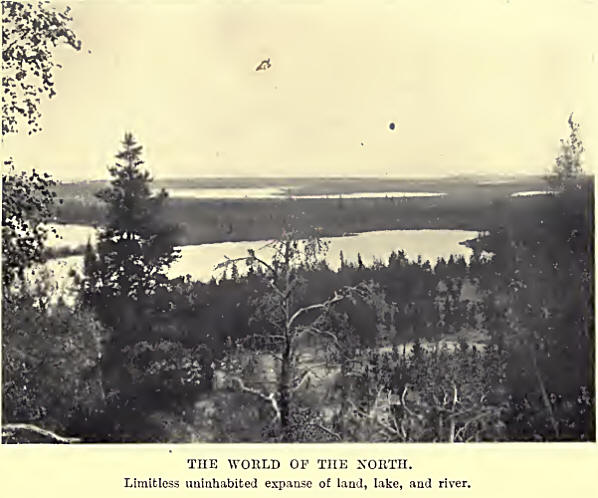

To anyone who valued, with the fresh outlook of a

stranger, the intensity of first impressions, the world of the North

showed calm and of fathomless beauty and mystery, and dominated all;

yea, even the foreground of humanity. It was all-powerful, this vastness

of eternity, yet all forgiving; and one was constrained to murmur:

So great this beautiful earth,

So little our earthly being,

So let us pass; each in our own way.

It was in this vein, then, that I mused of the Frontier,

and Beyond, on early acquaintance.

Time had passed since the evening of my arrival. I had

been two days in Big River—two long days of delightful, ruminating

freedom amongst the older bushmon of the place. And now it w'as the

evening of the second day.

I sat at the only table occupied in the great, bare,

paintless, featureless, interior of the barn-like Boarding House of Big

River. I had finished the evening meal—a hungry man’s full fare of pork

and beans and potatoes, accompanied by the inevitable thick-rimmed mug

of hot tea—and looked round me with the air of one who is satisfied and

who has accomplished the final task of a long, pleasurable day. I knew,

in hail-fellow-well-met fashion, all but one of the half-dozen others at

the table. There were the Engineer and the Conductor, who had come in,

an hour ago, on the evening train— Minnesota Joe, a self-famed,

talkative trapper from the States—and Pete Deschambault and Louis Breau,

two French-Canadian lumber-jacks.

But who was the new-comer? That was what I pondered with

a half-hope that he might be an experienced canoe-man such as I wanted

to hire for a long journey. He was of middle age and uncommunicative,

this stranger who sat among them; he ate his evening meal preoccupied,

and silently. Undoubtedly he came from the quiet places and from the

hard trail. Was not his face furrowed and worn with exposure, was not

his hair rough and untended— and ate he not wolfishly, as a man who

always knows great hunger ?

When the new-comer and the two lumber-jacks had risen

from their meal and left the Boarding House, I addressed the

Train-Conductor.

“Seen new-comer before, Neal?”

“Ya, stranger. Name, Joe Ryan. He’s just in. Been

trapping or lumbering all winter.”

“He’s a talkative cuss, Neal; meditates as if he were

planning next winter’s trap line.”

“Ya, stranger, it’s the bushman’s way. They live not by

what they say, but by what they do. Words ain’t much use to them; my

trade’s different.”

“Yes, Neal, you’ve a persuasive tongue, and you make by

it. But is there any chance of this new-comer accepting hire for a

summer on the canoe trail?”

“I don’t know. It’s hard to hire those men for love or

money if the work don’t appeal to them. Going far, Stranger?”

“Yes. I leave on the long trail north to Brochet1 as soon

as ice moves in Crooked Lake. Stiff going, they tell me; few in those

parts have been right through. Bad rapids on the Churchill;

blind 4 takes ’2 on all the lakes.”

"Aye, I’ve heard tell o’ it, Stranger, dreary tales too.

But Joe’s your man, if he will go. He’s reckoned a good hand here.”

We parted then—each to bunk for the night.

Next morning, I entered into conversation with Joe Ryan

as we were standing together at the entrance to the Boarding House idly

enjoying the glorious fresh spring air.

"Do you feel it, man?” I exclaimed, turning to the

new-comer with enthusiasm. "This Earth’s awakening! this full, rich

flood, which, at the bidding of the mellow wind, trembles in every

timbre of the forest. The sleep of the snows is over. Is it not so?”

“Ya, Stranger,” he answered. “The iron hand is raised,

our stripping of the forest is done, the river and the mill can do the

rest.”

“Ah! Been in the woods, Ryan?”

“Ya.”

“Quit now?”

“Ya.”

“Know something about canoe and river work?”

“Well—I guess so, Stranger, been riverman and

lumber-jack, off and on, ever since I was big enough to work.”

“Know the north trail hereabouts?”

“No! Have not been long west. Come from the Ottawa”

(River).

“Well, look here, Ryan, the police canoe1 is in from

Green Lake—just arrived—I’ve seen Bob Handcock, the police sergeant. Ice

is rotting on Crooked Lake, and moving, and passage out is possible

inshore for light canoe. Hudson Bay Co. have failed to send me up

promised ‘breed' who knew the trail, and I’m going to move out how as

soon as I’ve a partner in the canoe. What do you say to tackling the job

? You can go back from Lake liek la Crosse, if you don’t want to carry

on after two weeks’ trial of it.” .

“Wall, Stranger, it might be done. I don’t know you, you

don’t know me—that’s a great risk on undertakings of this kind, but

perhaps we'll hit it off. You’re no Government,—no party, no big stores,

no following of camp cooks and freighters. What are you out for? Fur,

foxes, or prospecting?”

“No, Ryan, I’m going for none of those things. When

you’ve come off the Drive, when you’ve had your glorious ‘flare up’ in

the city, and your body and mind are sick and sore with months of summer

idleness, what do you long for? Do you not crave again for the freedom

of the backwoods; for the great silence; for the peace of the camp

fire?”

“Aye, aye, Mate.”

“Well, so am I here. There’s no rest in the cities. I go

to study the birds and animals, and all of nature’s things—and to bring,

for the Government, specimens for their museum.

“I travel, as you would travel—alone, caring not for the

ease and noise of retinue in surroundings which are Ino part of such

things. From maps I know something of the main lakes and rivers, and

leave the rest to bush-craft.

“What do you say, Ryan, will you come?” “H’m!—Ya, I guess

so, Stranger—never had a chance before to see that darned North

Country.” “Right, Joe! Shake! Get what you want in the store, on my

account—six months’ tobacco, mind—and be around ready to pull out first

thing in the morning.”

Joe Ryan, Riverman and Lumber-Jack

Joe Ryan was a hard man. Hard, by nature of his calling;

hard, at the bidding of his mind. He had an unforgiving countenance,

deep-scared and weather-beaten, with no expression that could be

defined. Indeed, his face was an uncommitting mask hiding the shrewd

brain which had fought with a full measure of the hardships of a

bushman’s life in the early days of the lumber trade; and which had

suffered in the seeking .of recompense and pleasure. His was a life, in

its naked ruggedness, which hardly constitutes a school for saints. Ryan

had gone through the bitter mill of experience, and he knew the full

joy, and the full sorrow, of weeks of debauch and devilry when off the

Drive.

But, now, at the age of forty-five—which is beyond the

prime of a lumber-jack’s life—he had learned that it was all wrong ;

that, somehow or other, he had made a mess of things. True, from the

beginning, he had known no other life. In Town he had spent his pay, as

the others did, and been called “a, good fellow.” And so it had been

easy to go on, difficult to halt, and impossible to go back. But of that

he made no excuse ; he was not built in that way. He had failed. Yes, he

knew he had failed; but he would carry out life to the end without a

murmur of complaint, without the slightest outward sign of repentance or

sorrow.

And Joe Ryan had never married—what burden he carried, he

carried alone. And, when judgment is passed by the Great Unseen on those

who have known the utter desolation of a loveless life, will not the

hand which points our fate be touched with a special tenderness and

forg'veness ?

For the rest, there was much in Ryan’s life to be

recommended. He had been born in the backwoods, of a race who fight hard

and die hard on the outer edges of the world, and he had learned his

craft, from boyhood, in a stern school. No better lumbermen stepped the

earth than those from his home on the Gauteneau River, none more expert

with the axe nor smarter on the logs; and proud was their boast among

the French-Canadian settlements on the Ottawa.1 .

Yes, Joe knew his wrork, as the best of them know it. He

was among the chosen of the old hands, and, though on the wrong side of

forty and not so active as of old, he could still compete with many a

younger man.

Such, then, was my Riverman—this man whom I had picked up

by chance at “The End of the Line,” without introduction or

recommendation, to be my sole companion on an unknown trail for five

months.

I knew nothing of the man except that I knew his

trade—which was a strong word in his favour —and it was long months

after that I really knew him as I write of him. As he himself said: “You

don’t know me, I don’t know you; and that’s a risk on a big

undertaking.” But he took the risk, as he had always done,—the risk of

mistake by a stranger at the bow paddle of the canoe on a dangerous

rapid; the risk of “falling out” a hundred miles, or a thousand, from

anywhere.

As for me—well, I was taking no greater risk than he was. |