|

One evening in May found us quietly moving along the east

shore of Lake lie a la Crosse, when the sun was lowering in the west and

a soft, damp-tempered haze hung around the bottom of the dome of the

sky. We were paddling along easily, enchanted in a measure, by the scene

and sound of our unbounded surroundings. The setting sun still lit the

shore ahead, enriching with the colour of gold the fresh young leaves

and the white trunks of the cottonwood trees, till they were fair and

fantastic as fairyland should be; while, on the lake, moved the low

murmuring lap of gentle waves coming and going in company with the light

northern breeze, and that made a laughing trickle as they broke on the

prow of the canoe. So intense wTas the mystic hush of evening, and

unpeopled northland, that we almost felt guilty that we would be

discovered in our quest—that quest that was not for fairies, but for

something almost as elusive : the haunt of the Sandhill Crane.

To-day, to-morrow, or the next day, we hoped to have luck

and find that which we were searching for, but who could tell!

Until an hour after sunset we kept on, listening, hoping

that the lone call of a crane might be borne down to us on the

breeze—But no ! nothing gave us hope—nothing; and the day was done.

Seeking night camping-ground we ran in where the shore

was bad, for we had to make a landing somewhere on a shore composed of

gravel, and granite and sandstone boulders. But the ingenious Joe jumped

ashore, and while 1 held out in deep water, cut and laid a bed of spruce

boughs at the water’s edge, and on that the frail eraft was smoothly

grounded, emptied of her load, and carried ashore as wind was rising.

The country behind the east shore where we camped, and

which we were searching along, was generally low and, although the map

in my possession was blank, we knew it must contain many forest-bounded

lakes, absolutely secluded from the disturbance of red man or white; and

it seemed possible that if any cranes were nesting in the interior they

might at some time come out near this greater sheet of water, and

perhaps, if seen, betray the secretive locality they inhabited. To go

haphazard into the forest to search would be as vain as “to look for a

needle in a haystack,” requiring many months to attempt, without any

certainty of any success.

Two days later found us groping in the forest, searching

for unknown, unnamed water, through country that had not even a game

path to show us our possible destination. The evening before we had

heard a crane call, clear and unmistakable, from high in the sky over

the forest. The call had been repeated; had grown nearer and louder

until, at last, we had seen the great winged bird come into sight, and,

ultimately, pitch on the shore of the lake. Breathlessly then we had

watched and waited, for it was as if we were searching for gold and were

feverishly near to it.

For a little time the bird had pecked among the gravel,

then risen heavily, got started in speed and equilibrium, and sailed

away over the forest straight back into the east. The bird’s manner of

going had the decision of one returning to settled haunts, and we felt

sure that if we could find a marshy lake somewhere in the area where the

bird had flown we would be very close to the real centre of our search.

So were we groping in the forest—east for a long

distance, then traversing roughly northeast and south-east. In our

search we came on more than one lake and had to make wide detours in

some cases to get past and beyond them, but in none did we disturb the

secreted crane, and at the end of the day vain had been our search

through belts of crowded forest and muskeg bog, where foothold was

precarious and stepping laborious.

Throughout the day we covered a large extent of country

and were disappointed to have seen nothing of bear, moose, deer, or

other animals indigenous to this territory. But where areas of forest

are great and closely grown it is really seldom that one sees big game

in summer-time. In fact, at this season, one might often be misled to

believe that there are none. However, that would be a rash assumption:

there is game in plenty, though to-day was a blank one, and all that we

disturbed was an innocent, awkward-moving porcupine, feeding among the

branches of a poplar tree, and a brooding spruce grouse which we flushed

from beneath an alder tree, where six eggs reposed on a shallow

gathering of dead brown leaves.

Over the evening camp fire we were forced to wonder if,

after all, we had made a mistake, and were to suffer the disappointment

of an error of judgment. Joe, no longer actively young, was feeling

tired and stiff after the long day on the trail, and was plainly

sceptical and inclined to be disheartened and give up. I, on my part,

was prepared to doubt my judgment of the day before —the bird, after

all, might have been a solitary one without mate or settled haunt, an

outlaw male roving broadcast where it willed, free and restless as the

four winds of the wilderness.

In the early morning, while the dew yet lay white on the

undergrowth, and mists lay cloud-like over the muskegs in the hollows,

we were out of our blankets and preparing to strike camp.

We had decided to give up : to go back to the canoe, and

continue on the long north trail.

'We were eating our hasty breakfast—tea, bannock, and a

slice or two of fried salt pork— when suddenly we both started to our

feet, each, in excitement, exclaiming quite needlessly “ Lord! what was

that ? ” as clearly and closely the call of the lost erane vibrated

through the morning stillness. The sound came from the north-east, no

distance ahead. Astonishment and delight lit up our faces; though the

incident decisively showed us how near we had been to utter fools, in

giving up when within reach of our rare and elusive quarry.

A few minutes sufficed to finish breakfast and start on

the trail. Our search did not meet with immediate success, and by eleven

in the forenoon our eagerness was rebuffed and considerably abated,

while we were still hunting for the lake that held the secret. But at

last we had our reward, in all its fulness since it had been so

difficult to attain, for, about half an hour later, we came on a small

marsh-bordered lake, and there, when we stepped out of the woods into

view, two great Cranes arose from its interior, uttering their call of

warning, above the peevish screaming of a large colony of Black Terns,

as they swung wide and high over the lake, disinclined to depart. Here

indeed was the lake we had been searching for, this forest-locked sheet

of water, lying calmly at our feet full of meditation and reflection,

and unaware that it held for us great treasure. The lake was angular,

and had one small island in the middle on which grew an ill-thriven tree

or two. On all shores there were extensive reed-marshes, broadly

stretching out into the lake, where water-depth was shallow.

We explored along the shore of the lake for some

distance, disturbing bird life of many kinds as we went, but ultimately

decided that it would be impossible to search thoroughly for the crane’s

nest without the aid of our canoe. This, would mean a very long arduous

portage, but Joe, my sturdy old backwoods-man—now as keen as I on the

quest—himself suggested it, and made light of the toil which lie was

sett mg for himself.

To begin with, our task was to blaze and clear a trail

back to our camp on lie k la Crosse Lake; so we set out on the

back-trail, seeking the line of clearest passage, and cutting out

saplings and overhead branches whenever they would interfere with a

clear way for man and shoulder-high canoe. At intervals a clean white

“blaze” was sliced on the homeward side of a spruce, pine or tamarac

tree, to show clearly our way ahead when we came to return with the

canoe. Our small hand-axes struck out quickly and unerringly as onward

we pressed.

By late afternoon a long distance had been cleared and

blazed, by constant toiling, and we thought we were near to our old

camp. Here we were at fault, however, and for an hour could not find our

proper course nor come out on the shores of Lake lie k la Crosse.

Although we did not know it at the time, we had got too far round to the

north—not much, mind you, but just enough to change the whole aspect of

the country and lead to confusion.

At dusk, after crossing a spongy muskeg bog with

difficulty, we came out on the inner end of a far-reaching inlet bay of

the lake. Joe was put out by this time and candidly lost. I, assisted by

the compass, was convinced we were north of our camp, but for once Joe

was “at sea,” and could in no way back up my opinion.

However, after a rest, my counsel having prevailed as to

direction, we cut south-east into the woods again.

We had not been on the fresh trail more than an hour

before we found ground we knew and camp. We were not long in rolling

ourselves in our blankets; and slept the faultless sleep of well-tired

and healthy hunters.

Prewarned by constringed wispy grey clouds of the

previous evening, we awoke in the morning to find a storm had burst.

For two days we were delayed, while a heavy south-west

gale scudded angrily over Lake lie k la Crosse and made it impossible

for us to canoe up-shore to the inlet bay where our blazed trail

terminated. Had we known at the outset that the storm was to last, we

would have cleared an overland trail to the inlet. But that would have

entailed considerable labour, so we waited for the change of weather,

trusting to luck, and it turned out that luck was not in good humour.

On the third day we were up at 4.15 a.m.— if my watch was

right—while the golden glow of dawn was in the east, and the sun was

still hidden behind the dark peaks of the spruce-tops. In the crisply

cool morning—for the thermometer registered only 4 degrees above

freezing—we started up-shore in the canoe, disembarked at the inlet, and

commenced the long portage inland.

You know how a canoe is carried ? . . . The paddles are

lashed to the narrow cross-bars— which are the seats of the canoe—in

such a position that when the canoe is upturned and hoisted over a man’s

head, the head slips between the paddle stems just before the spatulated

blades, which thereupon descend comfortably on to the broad shoulders of

the carrier. In lashing the paddles into position for canoe portage they

are longitudinally arranged so that the canoe will be fairly evenly

balanced when being carried—if anything, a little more weight should be

proportioned to balance behind rather than in front. A chestnut canoe is

a heavy man-load, somewhere in the neighbourhood of one hundred pounds,

and it is wise to load up carefully and comfortably before starting on

an undertaking that tries one’s strength to the utmost before the other

end of the portage is reached.

Meantime, to return to our undertaking, we had been

labouring for hours along the blazed trail, and it was not until the

afternoon that we reached our destination—the lake that contained the

cranes.

After a brief rest we launched the canoe: assuredly the

first craft since the beginning of time to intrude on the placid waters

of that unknown lake, set deep in forest seclusion.

We eagerly commenced our search for the crane’s nest,

urged on by sight of the birds who wildly flew from before our

neighbourhood, uttering once or twice their curious call. Our search was

a long one; all the marsh shores were examined in vain, and not until

evening, when on the island in the lake, did we find the nest. Here, on

a marshy point on the south side of the island, to our great delight, we

came on the long-concealed nest—a large platform of gathered marsh-wreck

built on the water surface among reeds; and therein two large oblong

eggs of medium buffish sienna colour (perhaps finely speckled) and with

spots and splashes of darker colour.

Now in the ease of rare birds’ eggs you doubtless know

that it is essential to establish their identity beyond any shadow of

doubt if the record is to receive recognition and be of scientific

value. This is usually done by securing one or both of the parent birds.

But in this case I had a double interest in wishing to secure the

parents: for all along I had never been sure of the identity of this

pan’ of birds—their apparent colour bothered me. Observing them through

Zeiss field-glasses they appeared buffish brown tinged in colour, not

the leaden slate-grey of the Sandhill Crane as I knew it in autumn in

the plains. (The red on the forehead was very bright, and the neck more

greyish than the rest of the specimen.) Was theirs strange plumage of

the Sandhill Crane, or could they be Whooping Cranes? Here was uncommon

interest, and I was more keen than ever I had been in my life before to

secure those specimens.

Joe and I soon planned a method of outwitting the cranes.

I, with my twelve-bore gun, hid among the willows on the island, while

Joe put out on to the lake in the canoe, paddled across it, and landed,

and hid himself and canoe in the forest to make believe that we had

taken our departure.

I had not long to wait in my hiding-place before my

excitement grew intense. The great cranes called, one to the other,

appeared in the distance, and soon were swinging overhead, examining the

lake beneath. Again and again they passed over the island where I lay

hidden, lowering in their flight, but not low enough—they wore very

wary ; provokingly suspicious.

At last, as one of the great birds came sailing straight

toward me, I thought it within long range and took my chance—Both shots

rattled on the great bird, but alas 1 it but faltered in its flight for

an instant, and passed rapidly away from my discomfited sight.

I felt all was over now—the great chance irrevocably

lost; but hoping against reason, I waited on until dark.

Neither bird returned, and sadly I put off for shore when

Joe came for me.

We left the nest and eggs untouched on the island,

deciding to sleep the night on the lake shore and visit the island again

in the morning in the forlorn hope that the cranes would in the meantime

return.

We spent a comfortless night, cold—since we had no

blankets—and tormented by mosquitoes.

Next morning we were early on the lake, and moved quietly

toward the island, while no cranes were seen or heard, foreboding ill

for our enterprise. But we were not prepared for the culminating

disappointment that awaited us at the island—when we came to the crane’s

nest it was empty!—the eggs had gone! Where? We could not tell; we could

only surmise that rats, crows, or the cranes themselves had destroyed

them or carried them off.

It was all a terrible disappointment. Great hopes

sustained until the final hour; then nothing but wreckage. For two years

I had dreamed of finding the nest and eggs of this species north of

Prince Albert, and this result when my dream seemed true!

Like everyone else naturalists have

their successes and failures. This was my dark day.

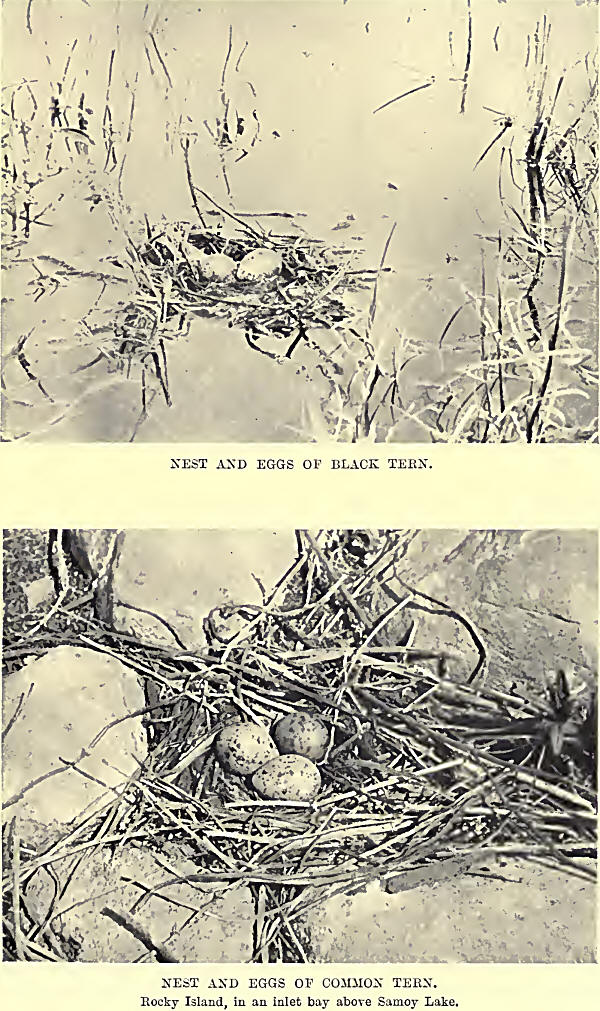

Before leaving the lake we spent an hour among the colony

of Black Terns that were just commencing to nest, and obtained some

photographs of the few nests that contained their complement of eggs. |