|

It is difficult to measure the distances one travels in

passing through new country, so one seldom attempts it. When the

question arises of travel about to be undertaken, or that has been

accomplished, one falls back, as a rule, on what maps one possesses to

scale off as best one can on a minute scale the straight distances as

they arc there shown. But such map measurements are at best but rudely

approximate, for seldom indeed can one follow a land or water trail

directly from point to point, as one assumes the course on the map.

Indeed, if one surveyed and laid on paper the actual course of a

primitive canoe1 in navigating a lake, while keeping land in view and

avoiding the unsheltered open lake on which it would spell death to be

caught in one of those rapid rising storms of wind so common to the

country, one would be astonished at the line that would zigzag and curve

in its progress towards its objective, for it would in all probability

take along shores of jutting headlands and through bewildering groups of

island, that ever interrupt and change the route of travel; and add many

hours’ labour to the patient voyageur. Over land it is the same; one

works forward to a distant objective, for ever on the look-out to avoid

the rougher going—thick undergrowth, swamps, muskegs, and such natural

obstacles— and endeavouring to obtain the most comfortable and

progressive route that the local conditions of the country offer.

Maps show the distance that I have canoed on the Great

Churchill River—or “ The English River ” as it is locally called—from

lie k la Crosse Lake eastward to its junction with Reindeer River, to

approximate 276 miles; while beyond the point of my departure from it it

continues easterly another 540 miles before it empties into the sea in

Hudson Bay. This is sufficient to make clear that it is a mighty river

in length, as it is also mighty in breadth and volume of water.

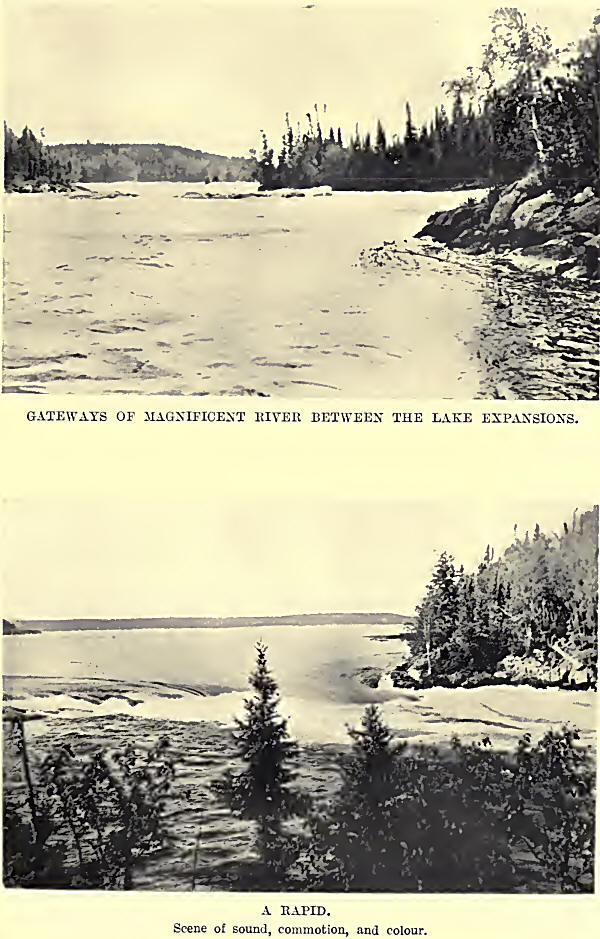

Throughout its course the Churchill River is an

extraordinary series of wide lake expansions linked together by gateways

and glens of magnificent river where waters gather in indrawing volume

to enter, and hurry, and tumble, and roar in their wild escaping onward,

ever onward to the next lake, and the next, in their incessant, time-set

journey to the sea.

On the section of the river on which I travelled there

were no fewer than sixteen large and beautiful lakes, ennobled by

solitude, rich in the undefined and the mysterious of the Unknown: each

resembling the other in that they were gems inset in the one type of

fair green forest country indigenous to that latitude; each different in

that the aspect to the eye was ever a changing scene of fresh beauty and

of fresh and gratifying originality. One never grew tired nor complained

of monotony. Stimulated by beauty, rather was one incited almost to

hurry from one fair picture to another, seeking what lay hidden beyond

the next river-bend, or the next island, and when that also was revealed

to wish in passing, and in the fulness of praise and satisfaction, that

the best of one’s friends in the world could be there also to share such

wealth of wonderful scenes. It was much too fine, it seemed, to be

revealed to just an audience of one.

Those lakes on the route occupied, approximately, 157

miles of the total distance, so that considerably less than half of my

journey on the Churchill was on actual river.

In the manner of our going I will trace the course of the

Churchill River to the mouth of Reindeer River.

Our solitary canoe, containing my able river-man at the

stcrn-paddle and myself at the bow-paddle, entered the Churchill River

from the north end of lie a la Crosse Lake. After passing down a short,

narrow stream of rapid water, we entered and traversed Shagwenaw Lake—a

lake which lies almost north and south. The north shore, with forest to

the water’s edge, was not far distant on our left, but on our right,

away out south as far as eye could see, stretched a beautiful sheet of

water interspersed with such a confusion of wooded islands as might well

perplex the voyageur should he be so unfortunate as to be doubtful of

direction. It was an invigorating day in early June ; cool, almost cold.

Bright sunlight lit up the full deep green of the peak-topped forests of

spruce and pine and glinted along the bleached, disfigured trunks of

storm-wrecked, long-dead trees, uprooted and thrown down here and there

at the forest edge in angular disorder. Broad earth and broad water were

beautiful: so also the heavens, beyond Space of remarkable atmospheric

clearness—grey islands of cloud lying low along the northern horizon, a

few faint white puffs and shallows to the east, and to the south a heavy

pillowed gathering of white and grey clouds, sun-touched on their

bankings with the south-east morning sun—overhead a great wide dome of

clearest, softest blue.

Without difficulty we found the outlet from Shagwenaw

Lake and entered a long stretch of river, wide and deep, and, for the

greater part, gently flowing. During the afternoon two rapids were

encountered: the first, not having excessive fall and having a

feasible-looking course down the edge of the rough centre volume of

water, we attempted to navigate, and successfully ran, after first going

above, and walking down on the rocks, to make a critical examination of

the rapid, for both of us were complete strangers to the river and had

not the almost essential native advantage of knowing where lay each ugly

water-covered rock and disconcerting whirlpool. The second rapid on

examination offered no canoe passage, so we portaged the canoe and kit

overland, and camped for the night at the lower end of the portage path,

which was but a faint, almost invisible passage down the forested shore,

used once a year, perhaps, in this thinly populated, almost depopulated

land, by some three dozen Indians journeying to the rendezvous of the

official Treaty Party at lie a la Crosse to draw Treaty money, and hold

a big powwow.

The following morning we resumed our journey and were

soon to learn that we had rapids and typical hard river voyaging to

contend with. During the morning we encountered three rapids. The first

we ran; and shortly after leaving it behind we passed, on the north

shore, the sandbars which lie at the mouth of the Mudjatick River. The

Mudjatick, or Bad Caribou River, noteworthy because it affords a

possible passage, though a hard one, to Lake Athabasca, rises in the

height of land north of latitude 57° and flows south about eighty miles

in a shallow winding channel before it joins into the Churchill River.

Thereafter followed other two rapids both too dangerous to run, so at

each we let the canoe down the Jess turbulent water close in to the

south shore: a process we accomplished by wading hip-deep, at bow and

stern of the canoe, over the uneven, bouldered, hole-dented bed of the

stream; loading the canoe slowly and laboriously downstream, holding

against the rude strength of the downpouring passing current.

About midday, after a strenuous morning, Joe and I

landed. I had secured three museum specimens and nine mallards’ eggs en

route. We lunched on the eggs—finishing the lot at a sitting. I assure

you that if one works hard one eats heartily in the North. It was June

2— where we lunched on shore Pin Cherry Trees were in blossom and Wild

Strawberries, and tiny purple Violets were in flower; charming colours

before the great background of evergreen forest.

In late afternoon, when nearing the head of Pelican

Rapids, we came quietly downstream on two moose standing in the cool

water, browsing contentedly on a beed of Water-lilies in the solitude of

a sheltered bay. Had it been open season, or had meat been necessary to

our existence at the time, they would have fallen easy prey. When our

scent was borne to them they left the water, and vanished in the forest.

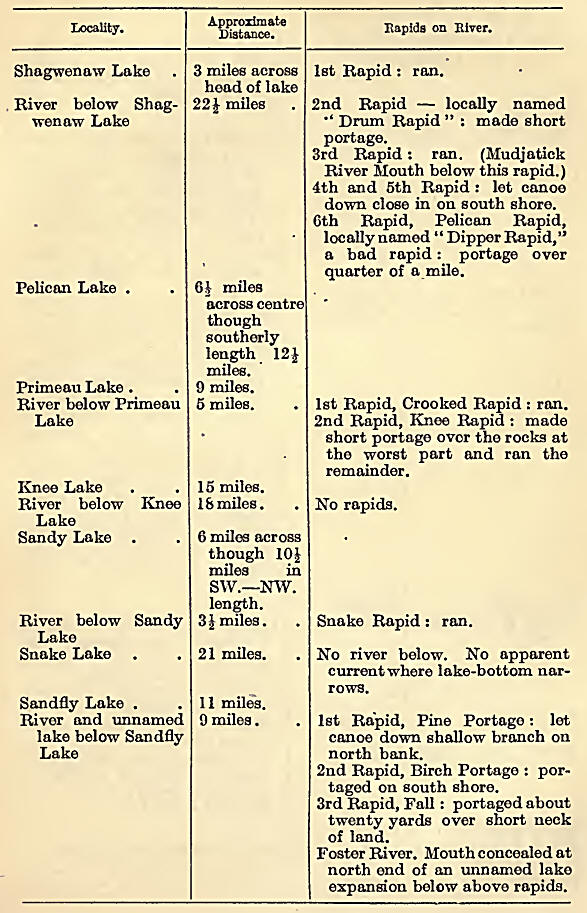

Before sundown we portaged Pelican Rapids— a roaring,

tumbling force of water that one heard rumbling in the distance long

before one came upon it. It was a wild, angry rapid, typical of many on

this mighty river—agitated waves when eager escaping waters rushed

together through the narrow, bouldered gateway; long, swinging swells

curling at the crests and breaking in silver foam; great waves rising

over boulders and rocks, and plunging into the depth beyond. Below the

entrance, ere the force died out in the great deep pool at the bottom,

were boiling whirlpools; and backwater eddies—swinging round to the

sides of the main stream and back into the head-waters of the angry

turmoil. On the shores were dark rocks tilted at all angles and broken

limbs of trees stuck in crevices where high water had lodged them.

Everywhere the waters were blue in the sunlight except where they broke

in silvery foam—an inspiring scene of sound and motion and colour. . . .

And there was an old friend: the Tennessee Warbler, whose kind

particularly haunt the shores of rapids,' singing joyfully of summer and

boundless activity, seemingly in competition with the prolonged purring

sound of the rapid, which clearly pleases him.

Next morning we passed the great marshes at the entrance

to Pelican Lake—marsh that teemed with duck in the full pride of

brilliant summer plumage. Mallard, Pintail, and Shovellers were the most

abundant, and Green-winged Teal and Golden-eye in lesser numbers. In

addition to those birds there were great colonies of Common and Black

Terns nesting among the marsh-reeds, and many Yellow-headed

Blackbirds—hoarse, shrill-voiced reed-birds, piebald in aspect, with

their black and yellow markings of sharp contrast.

The air was dotted with swinging groups of birds we had

disturbed, winging their way forward, then backward; while the water and

marsh held many more. It transpired, as the months passed and we

travelled on through lake and river, that this lake (Pelican Lake) was

recalled as the one containing the greatest abundance of waterfowl. It

held, however, one disappointment—there were no pelicans—at least- none

were seen. Possibly they once inhabited the locality, as the name of the

lake implies, but now have departed.

Pelican Lake was very irregular on all sides, with long

bays biting deep into the mainland; also there were many wooded islands,

mostly of fair elevation, standing well out of the water.

Small poplars grew chiefly on those islands and a few

white birch, while here and there a group of spruce and pine showed

darkly, and above the tops of the other trees. Willows bordered the

narrow beach of light granite stones, which marked the line between

water and soil.

On Pelican Lake we encountered difficulties. Crossing it

in the canoe we faced a heavy head wind and struggled against large

waves which the heavily laden canoe rode badly, for she rose stiffly to

the crests of the waves and pitched heavily into the hollows between. We

shipped more water than was comfortable and, once or twice, shipped it

in ugly fashion until we feared damage to our canvas-protected stores,

which lay packed in the centre of the canoe, if not a trifle anxious for

our own safety. Finally, about 3 p.m., we were able to reach an island,

and put ashore to wait until the wind should drop.

At 6 p.m. the wind had moderated and we were able to go

on, and reached the east shore of the lake. But then again we were in

difficulties, for along those shores we searched until dark without

finding the “blind” (hidden) outlet from the lake.

It had, altogether, been a disappointing day of hard work

and little progress.

Next morning early we found the channel through to

Primeau Lake, but again, during the day, we were in trouble, for in the

afternoon we toiled up a deep bay which in the end blankly terminated,

and it took us until evening to return to the position of our mistake.

On a great many waterways of the north, if without an Indian guide who

knows the territory, it is a grave problem to determine what to do when

confronted with two, or even three, long channels of water, to the

terminus of which the eye cannot see, and decide which is the one which

holds somewhere in its shores (secreted, perhaps, in yet another bay off

the main bay) the river outlet. Sometimes, on the dead water of the lake

at a shore point, or at a stone, or at weeds, it is possible, on close

examination, to find the slightest of down-flowing current passing the

stationary object; and then one may be positive that one is following

the right course. At other times it is one’s good luck to hear the faint

rumble, like a rising puff of wind in the trees (which one must be

careful not to confuse it with), of a distant rapid or waterfall, and

know that where it arises is the river. There is yet another sign which

sometimes gives one comfort when current and sound fail, and that is

some mark of Indian travel on shore: a willow or tree from which an axe

has robbed some branches and left the wounded ends, the black ash, or a

burnt stump, of an old camp-fire, or, best sign of all, a discarded

teepee— for those elementary, pole-framed, cone-shaped habitations of

the native nomads are seldom, if ever, erected except somewhere on an

Indian main “roadway.” But there are times when all those signs are

wanting and one must simply trust to Providence when confronted with the

puzzling irregularity of the shore.

The following morning, June 5, we found outf course soon

after pushing off. Below Primcau Lake we ran Crooked Rapid and part of

Knee

Rapid, after making a short portage over the rocks at its

head where the first inrush of water broke angrily over a rocky dip in

elevation. We had not long left Knee Rapid when a Black Bear was sighted

on the north shore, wading in the water :n search of fish, as is a

common habit with them in summer. The canoe was run ashore, and as the

animal ambled into the woods, for it had seen or scented us, I tried a

long shot at about 300 yards, but failed to bring it down.

The greater part of the day was spent travelling a zigzag

course through Knee Lake, a long, extensive sheet of water, and we

camped toward sundown well up to the north-east end, where should lie

the river outlet.

Knee Lake, like the others, was very irregular in shape,

and contained many islands. The rough hilly north shore was often less

densely wooded, and, here and there, ranged along the lake for a

considerable distance, were bare grass-hills scantily scrub-grown.

During the afternoon we came on a pair of Bald Eagles

nesting on a prominent point on the west shore of a side-channel on Knee

Lake. The huge, twig-constructed nest was on the top of a decayed spruce

tree, and contained one well-grown young bird.

To-day was a lean one for securing specimens. I note that

it was remarkable that I saw no hawks in this territory, and had not

seen one since leaving Lake He k la Crosse—though up to that time I had

seen a fair number and had secured one or two skins. It bears out that

which I have always experienced in Canada—that birds are remarkably

local, principally because, in my humble opinion, in such a vast

country, they are free to select ground of nature most attractive to

their habits of feeding, and most remote from their natural enemies. I

do not include man and gun as “natural" enemies, for they have invaded

the country after the habits of the birds were inherent. Large numbers

of some species, such as geese and cranes, have had the wisdom to seek

new haunts north of the line of civilisation. All of the edible species

that remain within the settled country, such as Sharp-tailed Grouse,

Pinnated Grouse, Ruffed Grouse, ducks of many species, geese, and

cranes—all are diminishing, some even threatened with extinction, like

the buffalo and the Prong-horned Antelope; and that though the

legitimate shooting season is open but for two brief weeks in the Fall

(autumn) of the year.

With extracts from my field diary I will follow out the

incidents of the remaining days we voyaged down the Churchill River;

extracts which it is my hope will continue to serve to bring before the

mind’s eye of the reader something of the varied, wholly outdoor and

untrammelled aspect of this great northern waterway.

June 6.—Morning dull, threatening rain, high wind from

north-west. Astir before 5 a.m. Cooked breakfast, and, as customary, the

one meanwhile struck tent and packed canoe ready for embarking, while

the other was employed over the fire. Mosquitoes were very troublesome

when we came ashore last evening, and worried us all through the night.

At all times at this season mosquitoes are in great numbers, but when

they are particularly bad—swarming and biting with unshakable

persistency—it is a certain sign that rain is near. Those insects, and

black -flies and sand-flies at times, are the bane of summer travel in

Canadian north territory. Out on the water they never trouble one, but

on shore they pounce on one from the vegetation that is there, and are a

constant jar to one’s full pleasure. One should never set out, as I

thoughtlessly did, without mosquito curtains; I would never again

overlook to prepare against them. True they carry no disease, but in

numbers and capacity to torment they far outstrip the malarial mosquito

in Africa (Anopheles) in my experience.

We reached the east end of Knee Lake between 9 and 10

a.m. There were there, close to the-exit from the lake, a small log

cabin or two, on the north shore and on an island. Those were completely

deserted of Indian or halfbreed: no sound was there, no contented smoke

curled above the thatched roof to give welcome to lonely voyageur hungry

for companionship and the sound of human voices. The inhabitants had

gone, the men taking with them their womenfolk and their children, even

their dogs. They had gone, perhaps, to meet the Treaty Party, perhaps to

pitch their teepees at some favoured summer haunt where fish and fowl

and beast were sufficient to feed them plentifully.

Invariably those log cabins of Indians are built—as those

here were—on a site remarkable for the long stretches of water it

commands: the sharp bend of a river, or the junction of two rivers, is

most often chosen, where the hunter inhabitant can obtain, without

moving from his door, an extensive view down at least two great

watercourses, and see, perhaps, the passing of worthy game, and, seeing

them, would then set out in chase.

At this point of Knee Lake there was a pair of ospreys

nesting; magnificent, masterful birds— the “Fish Eagle” of the country.

Their nest was on the top of a dead jack pine on a drear hillside

scorched at some not long past date by a runaway bush fire. There grew

there now, among the charred and blackened debris, the little ad-venturings

of new green growth ; an uprising of little living things about the feet

of the grave, grey, dismantled masts of trees that were dead and but

monuments now of lives once lived.

When we were nearing the osprey’s nest the male bird was

seen to approach, against the wind on powerful wings, carrying in his

talons as food for the sitting female a small pike about twelve inches

long. This fish he carried not broadwise to the wind, but held parallel

to the body, and with the head facing forward, so that it offered little

resistance to the wind.

About 10.30 a.m. we passed the mouth of Haultain River, a

stream from the north, about 300 feet wide where it empties into the

Churchill River over shallow sand-bars. Here, in the marsh west of the

river mouth, I spent some time observing bird-life. Five specimens were

collected during the afternoon, and three nests of eggs were found.

It commenced to rain after midday and we got miserably

wet before evening. During the day the following birds were observed:

Leconte Sparrow, Swamp Sparrow, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Yellow

Warbler, Tree Swallow, Redwinged Blackbird, Belted Kingfisher, Snipe,

Bittern, Mallard, Shoveller, Golden-eye, Bluewinged Teal, Holboell

Grebe, Black Tern, Crow, Raven, Osprey.

June 7 (Sunday).—Awoke this morning after a miserable

night passed on water-soaked ground in damp blankets. The activities of

the mosquitoes on the 5th were sure forecast of rain, and so rain had

come. It rained all day, and we did not attempt to move on but sat tight

within the shelter of my small silk tent. I skinned the specimens I had

collected yesterday, while Joe did his best to nurse a spluttering fire

before the tent-door for the cooking of meals. Rain can be a most

disconcerting element when canoeing and camping-out in this fashion, far

from any settlement ; a steady downpour will very soon find a way into

every conceivable corner, no matter how well you have fancied you have

taken precautions against it, and the result is that before long you sit

among your far-carried, dearly valued possessions and see them in a

state of half ruin before your eyes. Then only sunshine can lift your

depression, and, in spite of your unpleasant experience, when Old Sol

breaks through again you find yourself gaily arranging your possessions

before its heat, and looking out on the world with a freshened optimism.

Rain was, however, by no means a constant tyrant, for we experienced a

beautiful summer of sunshine with days of rain a rare exception.

June 8.—Morning overcast after a night of heavy rain, but

the heavy clouds cleared about 10 a.m. and the day thenceforward was

bright and pleasant; the air crystal-clear as the sparkling water, the

whole North world pure with the intense cleanness of virginity.

To-day we passed down the rapidless stretch of river

between Knee Lake and Sandy Lake: a stretch sub-named Grassy River on

account of the waterway for some distance wending its way, in three

separate channels, through broad green marsh. The chief incident of the

day was the finding of a colony of nesting terns on a low, plant-barren,

wave-washed island, full note of which is given in the subsequent

chapter of “Field Notes.” While on the island, some time was spent

photographing nests, and, thus delayed, we were still short of Sandy

Lake when night approached and necessitated our pitching camp on the

river bank.

June 9.—We breakfasted in rain, and struck camp, to

continue our canoe journey under the same discomforting conditions. An

hour after leaving camp we emerged into Sandy Lake, and throughout the

day voyaged through it. Sandy Lake bore out its name, containing many

low broad points and bays of beautiful sand. Indeed, so clean and white

were the shores in many places that the lake was thereby of pleasing

fresh aspect in comparison with those already navigated. Here, too, and

on account of the composition of the beach, shore birds were found more

numerously than anywhere previously, and I collected ten specimens;

among them a pair of Sabine’s Gulls, of which I saw three. These are

noteworthy, for they were the only specimens of this species encountered

throughout the expedition, and possibly they are quite rare in this

inland territory. Further west, some two hundred and fifty miles, Ernest

Thompson Seton and Edward A. Preble made an expedition in 1907 down the

Athabasca River and adjacent waterways, and in their list of birds

observed do not record having seen a single specimen.

Late in the afternoon, close to an island in the

north-east corner of Sandy Lake, we came on a small settlement

containing fourteen inhabitants. Here (in the rude, unkept clothing of

an outdoor exile), we found a white trapper, by name Hans Madson—a

Danish-American married to an English-Cree half breed woman. Not an old

man, this ruddy haired Dane of perhaps five-and-thirty, yet were the

customs of his race well-nigh erased and his disposition imbued with the

habits and mannerisms of his redskin associates: only in colouring and

speech did trace of his origin remain; so far had he grown into the

likeness of his surroundings. His cabin was empty of every luxury of

food, and his eyes lit hungrily when opportunity was given him to

receive a portion of sugar and prunes in exchange for dried moose meat;

for his daily food was little more than dried meat, and fresh or dried

fish, cooked without seasoning and eaten without vegetable or bread of

any kind. He was undisguisedly delighted to see us, and told us we were

the only whites he had seen since the Fall of the previous year, when he

had been out to Prince Albert. He begged us to camp the night near him,

and this we did, sharing with him as real a European meal as scant

stores could furnish, much to his satisfaction and gratitude.

The boom in black fox farming was at its height in 1913

and 1914, and every good fox that could be trapped alive in the

wilderness was being caged and sent east to Prince Edward Island for

breeding purposes. Like every other white trapper in the Dominion of

Canada, Hans Madson was “fox crazy”: smitten with the mad desire for

great riches, as men are swept off a sane balance who join in a great

gold rush. He was obsessed with the thought of digging out dens of

priceless black and silver cubs, or the offspring of black or cross

parents. Now, however, the cub season was over, and his chance of

success, for the time, was gone. He had had no great luck—a few7 reds

and cross foxes he had taken—but, undaunted, still he talked of the rare

animals he had seen on frozen lakes and in snowed-up forest, and of

others his Indian friends had reported; and he dreamed with true

optimistic sporting keenness of the possibilities of success when the

next early spring should approach.

June 10.—In the early morning we bade goodbye to Hans

Madson, who looked on with melancholy visage at our departure : God knew

when next he would see a white man! Not likely another to pass his way

this summer, nor any summer, for he had pitched his can ip off the route

of the red man’s trail—off such trails as rare, adventurous, self-exiled

wanderers of the white race turn curiously along one or two days in a

score of years. In olden days Indian tracks from the Reindeer

River—Foster River territory radiated from the Hudson Bay post at lie a

la Crosse, and this stretch of the Churchill River was a well-used main

route, but later, a shorter and easier north route developed to the

Churchill, from Cumberland House via Sturgeonweir River to Frog Portage,

and from Prince Albert via Montreal River and Lac la Ronge to Stanley

Mission Post.

Soon after we had bidden farewell to Madson the canoe

entered the short stretch of river that led on to Snake Lake and we ran

Snake Rapid, the only rough water on our course to-day. Thenceforward

the day was occupied in travelling through Snake Lake, a lake of some

twenty-one miles length from western to eastern extreme. The shores of

this lake had some prominent formations of vertical sand-bank, or small

cliffs; especially on the north-east shore. During the day much

bird-life was observed, and some nests and eggs collected at points we

landed at. Toward evening we camped well to the east of Snake Lake

within view of a solitary deserted winter post of the Hudson Bay

Company. This day witnessed a favourable change in the weather, for

about noon the rain, which had been with us for the last four days, gave

place to clearing skies and periods of sunshine. Charming was the

evening at our night camp: late western sunlight rested with golden

richness on the eastern 6 wooded shores, while below the curving,

changing shore-line the broad lake water lay becalmed and wholly placid

and blue, and a perfect mirage of leaved forest, scarred banks, spotless

pebbles, and dainty sandpipers was reflected on the immediate lake

margin. Overhead—with similar instantaneous sight, and marvellous

quick-changing flight of Swift or Swallow—swinging, plunging, rising

through the cool, balmy, rain-purified air, flew a pair of Nighthawks,

feeding on insects the while they emitted their hoarse, grating call,

which is associated with summer evenings anywhere in Canada; though

perhaps most familiar of all to those who camp outdoors by lake or

forest. Such sounds, and a few others, are inseparable from Canadian

wilderness; typical in their own country as the call of the Curlew or

peevish Lapwing on the dreary, wind-swept, highland moors of the British

Isles: such the maniacal, laughing cry of the Loon (the Great Northern

Diver) heard on nearly all backwood freshwater lakes; such the eerie

wolf-howl of the Coyote on the western plains.

June 11.—A day of perfect weather—very pleasant for

canoeing. Progress to-day was marred by our missing our true course when

east of the deserted Hudson Bay Cabin. There we entered a long false bay

to the south of the turn beyond the Post and had three hours’ fruitless

paddle to and from its blank extreme before we were again back on an

open course, where we discovered a slight sign of current to definitely

point the way.

About 3.30 p.m. we entered Sandfly Lake, a lake of lesser

size than Snake Lake. This proved again to be a lake containing a great

many islands similar to Shagwenaw, Pelican, and Knee Lakes of those we

had thus far voyaged through on the Churchill. Some of the islands were

of fair elevation and were wooded, others were low-lying surfaces of

rock and boulders with a scant, ill-thriven growth of grass. We landed

at a group of the latter wbere large colonies of terns and gulls were

nesting. Of those I made observations and notes, and collected a few

rare shore-birds. Before departing we gathered some fresh eggs to

augment our food supplies, counting them a great treat since they were a

change from our regular diet of bannock, salt pork, wild duck, and pike.

Pike and black and red Suckers were the only fish I caught on the

Churchill River—no trout were seen ; not even on Trout Lake.

This day I observed a single Chipmunk—noteworthy, as I

had not before seen this pretty little animal on the Churchill. A

Porcupine was also seen landing on the shore after swimming across the

expanse of water above Sandfly Lake. He proceeded to climb a poplar tree

to feed on buds and leaves. This was the first occasion on which I had

seen this species in the water. It appeared not to relish its immersion,

for it shivered with cold, and perhaps with fear, when it landed.

June 12.—We reached the exit from Sandfly Lake in the

afternoon and passed into swift-flowing river where bad rapids were

encountered and canoe navigation became impossible. This meant hard

labour, but, as it was all in the day’s work on travel of this kind, we

stuck to our task, with the result that three rapids were overcome and

an open course lay before us at camping time. At the first rapid—Pine

Portage—we waded into the water and let the canoe slowly down a shallow

branch of the river on the north side; at the second—Birch Portage—we

portaged the canoe, stores, and specimens overland through the wood on

the south shore; and at the third—Pall Portage—we again portaged, but

only over a narrow twenty-yard rocky neck, to evade the fall that was

there, for the water below was navigable.

To travel, as we did, without an Indian guide to lead

exactly over the recognised route—which is invariably the quickest and

least laboursome route, and the outcome of knowledge handed down from

one generation to another—meant that when no human trace could be found

on shore, such as an old portage path, when navigating rapids, or where

friction of feet had slightly whitened a vague line over an exposed

platform of rock, we simply had to aet on blunt individual judgment in

accomplishing our journey; and blundered on occasions and gave ourselves

extra labour. On rare occasions we saved labour, as in this ease, for a

small map I possessed stated that there were four portages at this part

of the river, while we only actually made two, though a third would have

been necessary had we not succeeded in letting down the canoe at the top

rapid. However, travelling guideless as a rule increases the labour and

risks, and certainly means loss of time; yet, even so, there is

something most attractive in attaining to complete independence,

complete freedom from reliance on others, which is most typical of the

primitive spirit which the North makes known to you, and approves. And,

beyond the pleasure it gives to be able to go where you list through the

wilderness, and risk what you list, the extra labour you undertake has

behind it, as all labour that is difficult must have, a spiritual

satisfaction and reward: for among red men or black in British colonies,

the prestige of our race is surely upheld by those who, when occasion

arises, can stand up alone, endure alone, and accomplish alone,

admitting no weakness to the eye of the critical native. Many an Indian

expressed great surprise at my travelling unguided through their

boundless country. Foolhardy it must have seemed to them who knew the

difficulties and dangers; yet none called me a fool. Rather were they

ready to be my friends'—not on account of myself, but because their

simple imagination painted me like the adventurous White Chiefs of our

earliest settlement, who wandered far and had great knowledge, and whom

they were willing to serve as subjects.

June 13.—Having secured some specimens yesterday—among

them an adult Northern Bald Eagle—I was busily employed skinning all

morning. .

After lunching we again pushed forward, our course

swinging well into the north-east up the lake-like expansion that lies

between Sandfly Lake and Black Bear Island Lake. Passing the

neighbourhood of the mouth of the Foster River —a river of considerable

size flowing from the north—no sign of its outlet was seen, and I have

since learned that that was because it empties into the Churchill in the

bottom of a deeply inlet bay.

Toward evening we entered Blaek Bear Island Lake through

its maze of channels which flow between the large islands that bloek its

entrance and obscure extensive view. Like the shadows of a big problem

were those islands which were crowded in and almost made prison walls

about us, leaving us anxious to solve the riddle that would discover the

doorway of escape and give again the freedom of the open road. Nowhere

do I recall such another eerie, shut-in scene as this. But in an hour or

so we had worked our way through to more open water and pitched camp for

the night on the north mainland of the lake, viewing, across the

shimmering, dead-calm water, and over the tree-covered contour, a

glorious sunset among grey and white clouds that had retired to the

horizon from the great blue open sky.

No less ungenerous than on the days that have gone before

are my entries and remarks this evening on mosquitoes and black flies.

They give no peace when on shore: they truly are the curse of summer

travel in Canada.

June 14.—A lovely morning; calm, and clear, and warm; the

continuance of a spell of fine weather without drawback to voyaging. We

did not leave in the canoe at once this morning, but explored in the

dark forest behind camp among fallen limbs and trunks lying about on the

rough, hillocky, moss-covered underbed of the woods. Many of the trees

were picturesquely lichen-grown with whitish, close-clinging plant, and

with scattered tufts of hairy, moss-like, pale-green plant. At the edge

of the forest was an eighteen-inch growth of green grass and weeds.

Forested hills sloped upwards from the north shore of Black Bear Island

Lake, and at the summit in some cases an outcrop of rock and large

boulders protruded prominently. The lake was some fourteen miles in

length, and while we remained on it we never quite forgot its somewhat

frowning, shut-in aspect. Even birds seemed to shun the neighbourhood,

for few were seen, and I recorded it the worst I had so far travelled

through in that respect. It has not been common with me to hear the red

squirrel’s chatter in this territory, but here I heard one to-day. While

speaking of creature sounds, I am reminded that it was on this lake that

I first noticed the absence of frog-croaking in the evenings, and it was

not until reaching Stanley Mission on June 23 that they were again

heard. Unfortunately I was too busily employed with other subjects to

investigate their apparent absence from this area—a stretch of about

seventy miles of watercourse. No black bears were seen, and in

supporting its nomenclature this lake was as disappointing as Pelican

Lake. Probably, when the course of the Churchill was mapped, a black

bear was seen on one of the islands of the lake, and therefore the

name—a name selected on the spur of the moment, without perhaps grasping

any very great and permanent characteristic. On the other hand, I, in my

haste onward, might easily miss such a characteristic, did it in reality

exist, therefore it is merely a passing personal . impression that I at

present record. Had I been the original surveyor I think I would have

chosen “Eerie Lake” as name for this strangely silent expansion of dark

water, wherein were closeted ghost-like citadel islands, and wherein I

never quite threw off the impression that I had intruded on a sanctuary

of spooks and fairies of long-past ages.

June 15.—Day again fine. Noonday sun high overhead,

giving the broad earth fulness of summer, and its living season of

growth. How blithely it lifts the spirit! How different this to the

sun’s low, short circuit in winter over land then dormant!

Characteristic of the country are the cone-peaked tops of

Black Spruce on the sun-lit hillsides, their branches drooping down a

little in extending horizontally outward; in this respect differing from

the White Spruce, which is more straightly outgrowing.

Passed the rapid at Birch Portage about 3 p.m. and

entered Trout Lake. We let the canoe down through the troublesome

current at the top of this rapid and ran the remainder. We camped for

the night on Trout Lake.

It is now twenty-four days since we left He a la Crosse

Post.

Joe to-night caught a pike weighing seven and a half

pounds when trolling with a small blue phantom minnow.

June 16.—Spent till noon to-day looking for right course

on Trout Lake. Yesterday headed out north-easterly in following the

small survey map in my possession, but found no outlet. Today, in the

forenoon, canoed down the east shore, poking into all side-inlets—but

without avail, and we lunched at Birch Rapids, from whence we had

started yesterday. From there we set out due north, and found our course

through.

About 2.30 p.m. thunderstorm and squall broke over us

when in mid-lake, and gave us a rough time until we reached inshore,

where we lay up until evening; then travelling onward, when the wind

went down, late into the night. We shipped a lot of water in mid-lake

when struggling against the great waves that arose, and at one time

feared for the safety of our craft, but finally we got through with

little more than a thorough wetting to our persons, the stores and

specimens saved by the tarpaulin which I always have laced over the

canoe-centre against rain, or spray when running rapids. Such a

tarpaulin, and a light platform to keep the kit raised off the canoe

bottom, are essential for protection against wet on long, rough journeys

of this kind.

Saw first two blooms of Wild Rose or Briar to-day.

Dragon-flies are now about the shores, and have been in

evidence for the past three or four days. They commonly fly back and

forth at height of the tree-tops (say 40 to 50 feet) or else very low

around the roots of the willows on shore ; to rest on occasions out of

the breeze on the sand in the bays.

Daily I note ornithological observations, and continue

collecting specimens, but these are omitted here as I deal with them in

a later chapter.

June 17.—Up at 3 a.m. and away early with the desire to

make up for time lost on Trout Lake.

Morning very dull and chilly, with wind from the east—it

looked like rain, but the sky cleared later in the day and there was

none. In early morning entered the north channel of the two riverways

which run past the large island which lies between Trout and Dead Lake.

Here we had to pass four rapids; at the first two, Trout and Rock Trout

Rapids, it was necessary to run ashore above and portage the canoe and

kit overland to quiet water below—laborious work over the rough ground

with the huge loads we piled on our backs to lessen as far as possible

the number of journeys back and forth on the portage trail. After we had

finished at the second rapid I put up my rod and fished the deep,

swirling pool at the top with a small minnow, hoping that I might see

trout. Here I hooked two great fish, not trout, alas! but pike. The

first one finally broke, taking the whole of my tackle; the second,

after some twenty minutes’ play on my trout rod, I landed—a pike

weighing 18 lbs., measuring 3 ft. 5J in. in length. Hitherto, until that

canoe voyage, I had always looked upon pike as an unclean,

poor-quality-food fish; but on the Churchill River, and elsewhere, we

caught those fish almost daily at times, and thoroughly relished eating

them. Of course, living as they did in clean cold water, those fish were

of particularly good quality, and, besides, real hunger cures many a

fanciful aversion.

Resuming our journey we ran Light Rock Rapid and the

nameless one below, having some exciting moments on the latter, which

was stony and very rapid, and somewhat dangerous, but through which our

canoe travelled headlong, like the wind, unscathed. And so out to Dead

Lake, the shores of which were high and rocky, timbered as usual with

willows, poplar, spruce and pine. Camped for the night well to the

north-east of Dead Lake.

During the day, on a marsh in the river, we saw a fox

prowling, searching for fish or waterfowl. Unaware of the canoe for a

few moments, the animal allowed us a full view of it, then, as it saw

us, but a glimmer of rusty red and white-tipped brush as it leapt ashore

with great bounds through the marsh and into the forest. It is not often

that a fox is thus seen during the day in summer, in the open, in

country which is for them one vast wilderness of forest cover.

June 18.—This morning we paddled out into the south-east

sun, while before us were the silver-glinting, sun-lit waves that ran

merrily with a moderate breeze. The short remaining distance on Dead

Lake was soon covered, and we again entered a connecting link of

river—the link between Dead Lake and Otter Lake. Here we spent all day

getting past rapids which had principally to be portaged.

At Great Devil Rapid, the first of the rapids here, we

encountered tough opposition to travel. Portage was necessary—a portage

of excessive length, which gave us incessant labour until lunch-time in

effecting the transport of the canoe and stores down to the foot of the

dangerous water. The portage was sixty-four chains in length, over

rough, uneven ground, through forest that skirted the banks of the

river. Joe, heavily laden, made three trips over this portage, and I

five, for, fitting in our work to save time, as we always did, I went

back for a load while Joe prepared lunch, and again for a final one when

he washed up and packed our belongings in the canoe. Therefore the

distance Joe travelled on that rough portage amounted to almost five

miles, and mine to eight miles—all over rough country ; and one-half of

those distances, the down-trail half, accomplished while carrying heavy

loads. Thus you can conceive the nature of hard river work which the

voyageur has to contend with —work so hard that I think it can

truthfully be said that no white man can accomplish it who is not

accustomed to it. Hardened though I had been with previous outdoor life

on the Saskatchewan Plains, I well remember how tiny my first packs

seemed in comparison to Joe’s 60 lbs. to 100 lbs., and how I perspired

and laboured with them, and how impossible it seemed that I should ever

be able to carry such a load as he did. Yet to-day my loads could equal

his—so can man harden his will and muscle to any task in the face

of necessity.

Overcoming Great Devil Rapid was our morning’s work, but

there our difficulties were by no means at an end, for we found we had

yet two more portages to make this day, each necessitating the unloading

of the entire contents of the canoe, the carrying of heavy loads to the

bottom of each portage, and, finally, the carefully balanced repacking

of everything into our frail craft, so that we would, each time we

embarked, enter the water snugly compact and weather-worthy.

Below the third portage we camped for the night, after

having there cut and cleared a portage pathway through the forest, as we

failed to find any old track made by Indians. The river above this rapid

broke into more than one channel, and apparently they evade this last

rapid by taking through, or portaging, at one of the other branches. No

one could run the water we encountered in a canoe.

Fished with fly in river to-night, but saw no sign of

trout. Caught 5-lb. pike on minnow.

Shot two specimens—a Northern Raven and a Grey-Cheeked

Thrush.

June 19.—Mosquitoes and black flies were particularly

virulent last evening; it was calm and close—omens of a weather change,

and sure enough all to-day it rained heavily. In the morning we decided

it was too wet to travel on account of portages ahead where stores would

be soaked were we to uncover them for pack transport overland.

So we stayed in camp all day, I skinning and looking over

my case of specimens, Joe cooking meals over a spluttering fire, and

baking a few days’ supply of sour-dough bannock from the sack of flour.

The 5 lb. pike caught last evening was gone in the

morning from the tree on which it had been hung. A bear had taken it,

for claw marks were on the bark where the thief had reached up to

plunder our larder. I could well imagine the brute in the dead of night

contentedly licking over its lips when it had finished the meal as it

ambled away into the forest, well pleased at

scenting and finding such easy prey; perhaps almost

laughing up its sleeve at our impending discomfiture.

June 20.—We awoke to find the rain-storm past, and,

refreshed with yesterday’s rest in camp, we made an early start,

embarking at 4.30 a.m.

Soon the great easy-flowing river narrowed, and we heard

ahead the unceasing rumble of falling water—we were coming to Otter

Rapid. Arriving there, and after making the usual careful survey of the

agitated waters, we decided that no likely channel presented itself that

could be run; therefore we would attempt to let the canoe down along

shore very close in to the bank. Into the water we got, clothes and all,

till it swept high and forcibly against our thighs, one grasping the

canoe forward, the other astern. The shore proved rough to let craft

down: strong side-swinging inshore waves and eddies caught and strained

the canoe, and almost swept us off our feet as slowly, feeling for

precarious foothold, we carefully stepped and stumbled along over the

rocks and boulders and pockets of the river-bed. Nearing the foot of the

rapid we made a short portage across a rocky point and in doing so

cleared the last stretch of troublesome water. Soaked to the skin were

our lower bodies, from our jacket pockets down; but we never changed

into dry clothes, for we were inured to this sort of thing, and garments

were few. We shivered somewhat on occasions when we first got into the

canoe again after being in the water, but soon wind and sun, and the

heat of our bodies, dried up the clammy, uncomfortable wetness. Hardly a

day passed that we kept dry throughout.

Below Otter Rapid was Otter Lake, and by lunchtime we had

almost completed the distance on this nine-mile expanse of water, which

was full of high, wooded islands distributed in great profusion, as on

other lakes which I have previously described.

About 2 p.m., on entering the river channel between Otter

Lake and Rock Lake, we encountered more rapids. Here again we took like

deer to the water and let the canoe down Stony Mountain Rapid; then

passing on to Mountain Rapid, which we had to portage. Below this latter

rapid we cooked the evening meal; but did not camp, for we were nearing

Stanley Mission, and, excitedly eager for the society of mankind after

our long, lonely spell on the canoe trail, had agreed to keep on and

attempt to reach the post to-night. A twelve-mile sheet of open water

lay before us through Rock Lake— no more rapids between this and the

Post.

Memorable were the last two hours outside Stanley

Mission. Southwards down Rock Lake we paddled in the full content of a

perfect Northern evening, praying wind would not rise to detain our

eager passage, lilting snatches of half-forgotten popular songs,

snatches of Joe’s French-Canadian songs of the Ottawa River, even

snatches of the old Scotch airs of boyhood were amongst our mutual

repertoire this evening: each timidly singing with rusty, unskilled

voice, but each voicing surely the lifting of spirits from the gloom of

lonely days now that we anticipated meeting kinsfolk. Without fault, as

luck would have it, we steered a true course down the lake, which

appeared less irregular and confusing than many of the others, and late

in the evening, after hours of unceasing paddling, we came upon

narrowing shores which promised the foot of the lake and the location of

Stanley Mission. The light in the western sky lay low on the horizon;

the shores to the right and left darkened to solid blackness; the air

and the water were alike becalmed. In through the last long stretch of

lake glided the solitary canoe, our two figures, dark in the dusk,

rocking slightly as we flicked the paddles methodically in and out of

the water with easy, almost careless strokes—action that was habit after

months on the water. At last two light-coloured dwellings gleamed dimly

on an inland bay to the south, promise at last of the settlement we

sought. Into the bay wc glided; noiselessly we stole inshore with The

stealth peculiar to canoeing. Eagerly we listened, but no human voice

was there to give us welcome —we had not been observed, and apparently

the inhabitants had gone indoors to sleep. . . . A disconsolate

sled-dog, on a distant shore, gave forth a long, coyote-like howl . . .

then, again, deadly silence. We stopped paddling before an Indian teepee

that was just discernible on the dark shore and called out. No answer

came. . . . Again I spoke; footsteps shuffled, and there was a murmur of

gruff voices within the teepee; then an Indian hailed us, but in

response to my question, asking direction to the white trader’s

dwelling, he made no response—he did not understand my tongue. . . .

Down the shore a door creaked, suspense a moment, then a clear woman’s

voice rang out in English. We were dumbfounded. Was there a white woman

here? There must be. . . . Clearly the voice directed us. How sweet it

sounded here, how welcome the assuring instructions!—for we were

dog-tired after our long day (eighteen hours in all), and eager to land

and camp."

June 21, 22, and 23.—During those days we camped at

Stanley Mission Post; the 21st was a Sunday, and we took things easy, on

the 22nd much time was spent at the Hudson Bay Company’s post,

replenishing supplies, while on the 23rd it rained heavily, and

unfortunately delayed our restarting for a day.

Throughout the period we were at Stanley Post our chief

care was to protect our tent and belongings from the sled-dogs of the

settlement. They were a downright pest, so bad that Joe and I had to

take it in turns to stay at home and sit on the doorstep, so to speak,

to defend our belongings against their attentions. We lost a few little

things to begin with, in spite of our care, but the culminating offence

that brought our wrath down on them was when on the night of the 23rd

they raided our tent while we slept and devoured six loaves of bread

which the halfbreed woman at the Post had that day kindly baked for us

as a particular delicacy, and which were to have been a toothsome food

supply for the next month on the trail.

There was no Factor at the Hudson Hay Post, for he was

south at the Lac La Ronge Post at the time, and purchase of stores was

made through his halfbreed wife, who spoke Cree well, but only a very

little broken English, so that conversation was carried on with

difficulty; for at this time I knew but a few words of Cree. There was

only one more Hudson Bay Post between Stanley and my ultimate objective

in the north—that of Fort Du Brochet at the far end of Reindeer Lake—so

here at Stanley I replenished my stores to the extent of 150 lbs. from

the standard variety common to all fur-trading posts. Selecting a

limited quantity of almost every available edible article in the store,

my purchases were :—Two 24 lb. sacks of flour, 25 lbs. “Hardtack” ship

biscuits, 5 lbs. rice, 5 lbs. beans, 15 lbs. bacon, 8 lbs. salt pork, 5

lbs. sugar, three cans of syrup, 3 lbs. evaporated apples, 2 lbs. baking

powder, 2½ lb. bag of fine salt, 2 cakes of soap, 1lb. cut tobacco, 1lb.

black plug tobacco, three hundred 12-bore cartridges, one spoon troll

for pike, one tump line (for roping and carrying loads over portage),

two yards mosquito net, and one pair of socks.

The Provincial Government had arranged with the Hudson

Bay Company, previous to my departure, to take care of and transport

whatever specimens I collected on the expedition, so at their trading

post I packed 57 skins and 47 eggs for shipment, those I had taken sinee

passing lie a la Crosse post.

Stanley Mission Post is at an abrupt angle of the

Churchill River, for the down-trending waters flow, with current unseen,

through Rock Lake in an almost due-south direction to narrow, then

expand to broad river width, at Stanley, and swing again into its

natural easterly course. The scattered settlement is on both banks of

the river, north-west and south-east; however, the greater number of

mud-plastered cabins and canvas-covered teepees (wigwams), and the

Protestant church and mission, are on the north-west shore. There is one

island in the bay opposite the north-west shore. Wooded hills are behind

the settlement, while on the low ground there is clay soil in which good

potatoes are grown. I noticed Dandelions growing here, and surmised they

had been brought up at some time in potatoes or other foreign seed.

Stanley Mission Post is the largest settlement north of the Churchill

River. It contains about two hundred inhabitants, men, women, and

children; and about twice that number of dogs. Very few of the natives

are pure Indians, nearly all being a variety of castes of half breed.

All speak Cree. The Post, owing to its geographical position, might

almost be said to be on the outer fringe of the Frontier, for it is,

though distantly, in touch with the large northern town of Prince Albert

through the route which lies directly south, some two hundred miles in

length, via La Ronge Lake and Montreal River: therefore the race of

Indians is affected by contact with civilisation, as almost all Indians

are to-day, except in the most remote and furthest-north territories

which they inhabit—affected in purity,

in physique, in reserve, and the quiet grace of race

which indubitably marks, and marked, the full-blooded Indian.

Of our two great religions the Catholic faith appears to

be the stronger pioneer on the outskirts of civilisation in North-west

Canada, and beyond, for at a great many, surprisingly remote stations of

the Hudson Bay Company it has established missions where priests work

faithfully alone among the few somewhat pagan inhabitants that

constitute their charge. Therefore one comes to take Catholic missions

as a matter of course on the north trails, but here, at Stanley, was a

less common institution—a long-established Protestant mission which at

the time of its beginning must have been a great pioneering venture on

the part of the mission, and missionary, which undertook it, and even

now could give to a man exiled from his kind, and the customs of his

kind, but little comfort and reward except--ing a measure of

satisfaction to earnest conscience and devout determination. The

highest-up habitation on the hillside on the north-west shore is the

mission house, while the church, dominant and outstanding in this place

of tiny dwellings, is erected on the east margin of the settlement, near

to the shore. Inhabitants of Stanley say the church was built sixty-five

years ago, and as it is the most pretentious erection north of the

Churchill, and has been so for many years, I will endeavour to describe

it. The architecture, if it could be so called, was crude, almost

barn-like; such as could be described was Gothic in design. The church

was constructed with timber above the foundations, which were of rough

stone imbedded in and plastered with clay. The main aspect was that

which most churches bear in greater or less proportions—a tower rising

high over the entrance; a nave forming the main body of the church,

lighted from clerestory windows; and narrow side-aisles behind columns,

and below roofs in taking to the upper walls. There - was a small vestry

in the rear, but no transept, and so the pulpit stood on the right of

the congregation at the head of the nave. There were seats in the nave,

and bare forms against the walls in the side-aisles, while in a space in

the nave at the rear stood a simple, antique-looking font, which I

thought the most beautiful thing in that strange place of worship. The

whole was impressive, since it was obviously the outcome of the rude

labours of necessity of men who wished beyond all else to advance the

faith of God to the outermost corners of the world. A large wood-burning

stove stood at either end of the nave, for heating purposes in winter,

and from those stoves unconcealed galvanised smoke-funnels ran overhead

to find an exit finally in the roof; the whole being one of those harsh,

incongruous necessities that one finds in out-of-the-way places and

which are most disturbing to one’s sense of good taste. The church, well

packed, could seat two hundred people. All hymn-books were printed in

the Cree language. The whole interior of the church was kept in some

degree of preservation with paint, paint that, alas! in effect was

almost vivid rather than gravely peaceful; again, no doubt, a

circumstance occasioned by necessity—lack of colours to select from, and

the impossibility of having an accurate blend sent in to that remote

station by any but a particularly enthusiastic craftsman. The walls, and

ceilings between the rafters, were painted pale blue; the column white;

and, for the rest, all woodwork was painted dark reddish-brown—the

cornice, the column caps, the window-frames, the roof-rafters, and the

seating—while the window openings contained leaded glass divided into

small oblong panes of red, yellow, blue, green, purple and white in

glaring contrasts. I came again outside, and was almost glad of the

grave greyness and ill repair of the exterior, which appeared to be in

the last stage of decay; moss growing on the weather-beaten, paintless

grey boarding, and many places broken and growing to an open wound.

Leaving the church, the door was closed and secured with

a piece of string tied to a nail.

June 24.—It was daybreak at 2 a.m. and the rain was

easing outside the tent. By 4 a.m. we were hauling up tent-pegs and

preparing to leave Stanley. There was a light wind from the north, but

it was dull and cold—more like Fall weather than that of June. Small

openings of clear sky showed scantily through dreary, dull-grey

clouds—disclosures more blue than any of a common summer’s day, and it

is probably on account of the strangely cold atmosphere that there is

such brilliancy to-day.

Proceeding on our way down the Churchill River, we soon

came to Grave Rapids, below Stanley Mission, and nearly upset the canoe

in running them. We were running the rapid on the left of the swells

that surged down the middle, when, in a flash, we were too far into

them, and shipped a canoe-load of water before we righted on out course

and fled on swiftly to the foot of the rushing water. Then, lurching

heavily, we pad-died ashore and emptied the canoe, finding as before

that the canvas cover had saved most of our provisions and kit from the

water.

Thereafter, after some delay in finding the inlet, we

came on through Rapid River Lake.

About 2 p.m. we portaged at the rapid above Drinking Lake

and again had lake expanse before us and an unobstructed stretch of

water through which we made good progress. The shores of Rapid River

Lake and Drinking Lake were similar to those previously passed, except

that neither were very confusing in outline.

At 4.30 p.m. we reached the foot of Drinking Lake and

made a portage at the entrance to the narrows above Key Lake, where an

island separates the river into two channels: a large main channel and a

small channel. Down on the rapid water of the latter we ran in the

canoe, thus evading the fall which obstructed passage at the foot of the

other channel. Here we camped for the night within hearing of the

pleasant sound of tumbling, hurrying water, well satisfied with our long

day, for we had covered about twenty miles as the crow flies and

overcome three rapids. A number of birds were noted, but none collected,

since they were either commonplace, or of species I had already

collected.

June 25.—On the water about 6 a.m. and proceeding onward

through Key Lake.

About 11.30 a.m. we reached the bottom of the lake, where

we portaged overland at Key Falls.

Below the falls, going quietly downstream, we came on a

very large brown bear. The bear, when first seen, was wading belly-deep

in the water on the outside of some reeds on the north shore on the

prowl for fish—suckers or pike, which such animals capture by striking

at in the water in lightning scrap fashion. Providence or sense of

danger stirred in the brute while we watched, for it waded leisurely

ashore and disappeared into the bush before we had even planned how to

get near enough for shooting. The animal gave no sign of having seen us

or scented us, and so we were induced to paddle down on to the south

shore of the river, and go into hiding opposite where it had been

hunting on the chance of its returning. There we lay up for two hours,

but our patience was unavailing, and disappointed we resumed our journey

at the end of that time.

In the late afternoon we made a portage at Grand Rapids

and camped for the night at the lower end. The portage at this rapid was

a long one, nearly half a mile in length.

Again and again I am prompted to exclaim in admiration of

the vastness of the Churchill River. After twenty-four days on the great

waterway, her lakes and rapids have not lost one whit of their

impressive strength and grandeur; unbridled force running wild; powerful

water-power worth many a man’s kingdom if only it were within the

boundary of civilisation. In such a trend of thought one is apt to try

to look into the far-distant future and wonder what changes another

century will bring and to what industries mankind will turn when they

assail this virgin country. Lumbering, though the timber is small in

comparison to the great trees in British Columbia and elsewhere, will

probably be the first industry to be taken up, while rich minerals may

be found, and good agricultural land; though on the river bank I saw no

promise of the latter, much of the ground surface of the forest being

bare rock and boulder where sand takes the place of soil. But no living

white man yet knows what the interior of the vast northern territory

holds; inland there may be great tracts of soil suitable for

agriculture. Only the waterways, where summer canoeing is possible, have

been roughly surveyed. Beyond them the maps remain a great blank space.

During the day I collected some specimens of birds and

found a number of nests. In the evening I caught a pike weighing 3Jibs.,

which I was astonished to find had an adult Cedar Wax-wing in its

stomach. Dissolution had not set in, the bird was intact, and easily

identified. Wax-wings prey much on insects, and I fancy this bird had

dipped to the water surface in pursuit of a beetle or shadfly, and the

ravenous pike had on the instant risen and seized it.

At dusk I took my rifle and went quietly back on the

portage path to the top Grand Rapid in the hope of seeing bear, but had

no luck, though bears at this season of the year frequent such places if

they are in the neighbourhood to prey on the shoals of black and red

suckers, many of which are easily cornered and captured in shallow

channels and pools in the angular, rocky steps of a fall.

June 26.—To-day we travelled Island Lake, the last lake

expansion between us and the mouth of the Reindeer River, where our

journey on the Churchill would end. Island Lake held beautiful scenery.

After leaving the east end of the lake, which was something like many of

the others in rough shores of bewildering outline, there lay before us a

wide expanse of water, the clean-cut shores of which had straight

distances of green grass and coniferous tree-trunks rising

perpendicularly from the earth, their bases unscreened by willows.

Nearing the north-west end of the lake there were a few pretty islands

where bright grass blended with the darker green of shapely poplar

trees. The water of the lake was clear, so clear that it sometimes

permitted a view of the clean, stony bottom through a good depth of

water.

In the afternoon, after spending some time searching

through one or two of the islands, we reached the end of Island Lake and

there located Frog Portage on the south shore opposite an island, where

the river takes a sharp turn into the north-east. Frog Portage is an

overland link into Lake of the Woods, which is the north end of the

Sturgeon weir River route, that runs 150 miles south to Cumberland House

and thence forty-five miles east to The Pas in northern Manitoba, where,

for the present, terminates the railway service on the Canadian Northern

branch now under construction to Hudson Bay. I made particular note of

the position of Frog Portage, which was difficult to discern until you

are almost upon it—as, indeed, are all Indian trails—and I cut a large

blaze on a solitary tree which stood on a bare point on the east shore

after resuming our journey, so that I would be warned when I approached

it on my return and might be sure of finding it, for it was by the above

route that I intended to return to civilisation at some distant date in

the future.

There were some Crees camped at Frog Portage : four

teepees containing one deaf old man and a number of women and children.

With the exception of the old man the male inhabitants were away

“freighting” stores north from Pelican Narrows for the Hudson Bay

Company. I photographed the gipsy-like dwellings, after I had overcome

the old man with a gift of tobacco, to the seeming consternation of the

female inmates, who in their acute shyness reminded me somewhat of

alarmed sheep.

Leaving Frog Portage behind we continued onward in a more

north-east direction than hitherto, until approaching darkness bid us

camp.

To-day I saw a Mink swimming rapidly ashore with prey in

its mouth. With my shot-gun I fired near to the animal as it landed, and

it dropped what it carried, which proved to be an eel fifteen inches

long, showing by deep-sunk teeth-marks that the strong, squirming thing

had been held in vice-like grip across the head to subdue it and prevent

its escaping. To-day, too, I again saw a Porcupine swimming in the

water.

Previously, on June 11, I had noted a similar occurrence.

June 27.—This was our last day on the Churchill River,

for about 2 p.m., after poitaging at Kettle Falls, we came to the mouth

of Reindeer River and turned north up that broad stream of crystal-clear

water that cut a well-defined line where it joined the more brownish

water of the Churchill.

Stiff paddling henceforth lay ahead: against current we

must now journey onward; no longer was our course downstream.

Somewhat reluctantly we bid good-bye to the stream whose

name and character had grown familiar and given us pleasure, and

thereafter faced the dim trail into the distant North. Always, on such

travelling as this, the familiar scene and the knowledge and experience

you collect go back to the Past, while ahead, round each bend, and

island, and point in your course, lies the alluring, unravelled unknown

of the Future. So like our lives !—the plan unfinished, the map of our

course to be drawn as each day leads onward. Unseeing what is in front

of us, yet in faith picturing scenes as we imagine them to be, and as we

would like best to find them.

But so far as the Churchill River was concerned our

travels there were ended, at least for the present. We had voyaged by

lake and stream for forty-seven days, twenty-seven of which had been

spent on the broad, beautiful waterway which I have endeavoured to

describe.

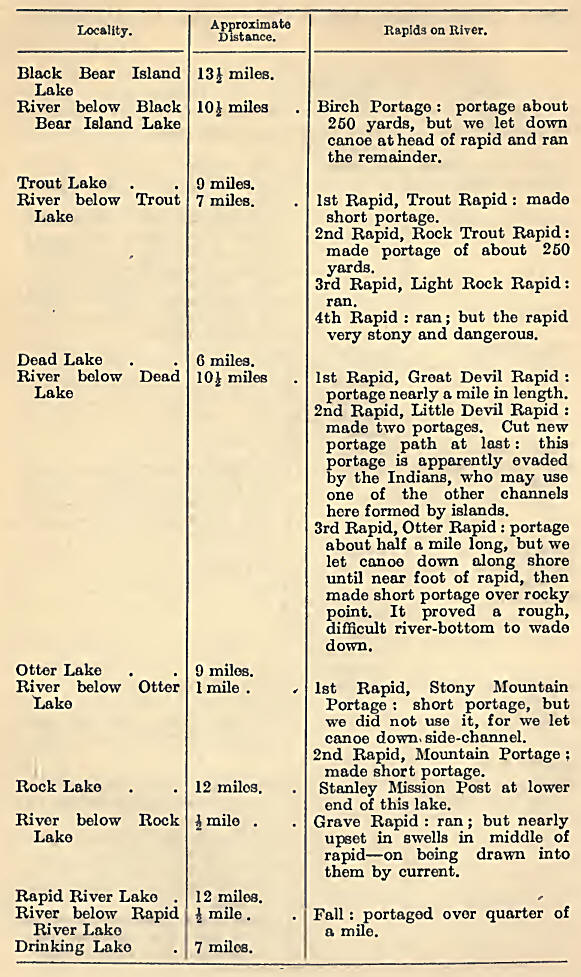

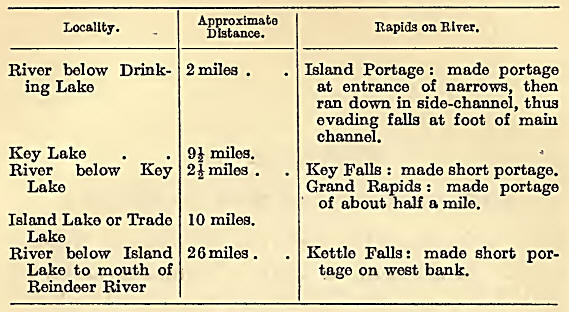

Below I give a summary of the Churchill

River from Lake lie a la Crosse to Reindeer River:

|