|

At the south end of Reindeer Lake, soon after striking

north from the great Churchill River, one is vividly made aware, even in

summer, that the land of vast Caribou herds has been reached. There at

the Indian camp at the outlet to Reindeer River you will find strewn

about the small Indian cabins, in untidy disorder, remains of many

Caribou—bleached hair, hoofs, and white, weather-washed

knuckle-bones—which even wolfish sled-dogs have given up chewing at in

distaste at their absolute poverty. Afterwards, as you pilot your way

northwards, through the great lake of forested islands, you will be

astonished, wherever you land, at the number of Caribou paths that lie

before you—clear-cut paths, worn down by the hoofs of countless animals,

following, Indian-file, one after the other over the cranberry,

moss-grown, sand surface of the woods—paths not grown over; unchanged

since the time of the last migration except that they bear no fresh hoof

imprint. Those paths are traced in many directions, but perhaps the

greater number, and those most deeply worn, are those which run north

and south. You have reached the great winter-haunt of the Barren-ground

Caribou (Rangifer arcticus).

Since the beginning of time, as far as men know, they

have always come here—Reindeer Lake! Assuredly not for nothing had it

been thus named.

In that particular territory the southern boundary of

Caribou migration may be said to be the Churchill River, though animals

have been killed on rare occasions as far south as Cumberland House on

the Saskatchewan River. But the great area of Reindeer Lake, larger than

a halfdozen English counties, is pre-eminently the favoured winter

feeding-ground.

In October or November each year large herds of Caribou

reach the north end of the lake, and apparently continue south chiefly

on the eastern shores. Thereafter they scatter abroad for a period, and

travel slowly from place to place, over frozen lake and snow-lain

forest, while feeding on abundant white moss and marsh-grass, and a

consideration of mud which they seem to relish.

In winter their method of feeding is to dig down to the

ground-surface with their remarkably sharp forefeet, and then to work

forward in the channel they have made in the snow, which is sometimes of

a depth of three feet or more. When the depth of snow is very bad the

Caribou prefer feeding in open muskeg valleys, between the more densely

grown forests, where the wind gets at, and sweeps away, part of the

covering, and the labour to reach the undergrowth is accordingly less.

Early in the year the does and yearling fawns again

commence to move northward, while the bucks remain behind to follow

later. They return not as they came, not chiefly on the eastern shores

of the great lake, but scattered broadcast among the islands of the

frozen lake, and on both mainland shores. The fact is that theirs is a

leisurely return, since there is no weather change to urge them to

haste—as is the case when the great massed droves hasten south—and so

they travel easily, and in food-seeking, scattered herds. There is

almost certainly a second reason for the leisurely return of the does

and fawns, and that is the maternal instinct of the does, for many of

them are with young that they will give birth to in early spring.

One can easily understand why those great herds of

Caribou travel south in the Fall. The undergrowth on the Barren lands is

plentiful, but there are no trees. When winter comes the wind, driving

over the exposed white surface, packs the snow hard, and an icy crust

forms through which it is difficult, sometimes impossible, to break for

grazing. It is, as it always is by nature’s arrangement of things, a

question of existence, this insistent migration of those animals. As the

thermometer drops in the Far North, and food and shelter become

difficult to find, the animals will band together and grow restive, and

pause from time to time to sniff the wind from the south with

question on their countenance. And one day, with proud heads up and

anxious eyes, they will commence their long travel through sheltering

forests where snows are soft and food is plentiful beneath the yielding

surface.

At Prince Albert, or any frontier town, you may on rare

occasions run across a Cree or a Chipewyan Indian who has ventured out

to the white man’s country, to “the people who live behind rocks”—as he

terms the white race that live in stone-built houses. If you question

him closely, you may hear of the great Caribou migrations which pass his

far-off wigwam at some nameless point in space and which provide him

with meat stores for half the months in the year.

If he narrates vividly his story will be legend like as

the tales of Buffalo herds on the North-West prairies half a century ago

or as the tales of the herds of Pronghorned Antelope—that, alas! have

wasted away since civilisation came to the prairies, and the fences of

the Canadian Pacific Railway held them hapless prisoners when they

longed to answer the insistent call to the south, and to change which

was essential to their existence.

In many ways I had heard of the migrations of the

Barren-ground Caribou, each new tale whetting my desire to witness them.

The Buffalo had gone, the Antelope were almost gone; mankind would never

again witness those great animal herds in their wild state. There

remained— beyond the pale of white man—the last of the roving big-game

race in Canada; the Barren-ground Caribou.

I had read at one time some records of Caribou in a work

entitled Through the Mackenzie Basin, which contained “Notes on

Mammals,” by R. Macfarlane, and I had written them down, though little

knowing that I would ever come to think of them again. Those records

were:— "Caribou observed passing in the neighbourhood of Lac du Brochet

(north end Reindeer Lake). Fall migration witnessed in October,

November, or December. Spring migration in April, May. Caribou seen each

year from 1874 till 1884: none seen from 1885 until the autumn of 1889.”

Those notes contained for me one main idea— that Lac du

Brochet was a particular winter haunt of the Caribou. That thought

caught hold and took root.

Hence you have found me entering the Land of the

Caribou—hence was I in the middle of August 1914 (beyond the reach of

knowing of war, which I did not learn had broken out until October)

approaching the height of land that occurs in latitude 59° and longitude

102° 800 miles, by the course I had travelled, from my starting-point

east of Prince Albert.

Passing Fort du Brochet, before entering the Cochrane

River, I had been told by Philip Merasty—an ancient Hudson Bay servant

and crafty hunter, and a fine old half breed who, but for his name and

elementary mission education, you would take for a full-blooded

Indian—that during the past three years the Caribou had been arriving in

their neighbourhood at an earlier date than formerly. It was in October

and November that Caribou appeared in former years, he said, but they

looked for them now in late August and September. Yet in his crude

diary, which I found secreted in his cabin caves some weeks later, I

came on the illuminating information that his son Pierre had seen the

first Caribou on frozen Reindeer Lake on October 21, 1913. I would

rather trust the diary record than the verbal one, and later experiences

have borne this out.

However, for the moment, I had been encouraged by the

Indians at the post to think that if I continued my canoe journey north

I would have every chance of seeing Caribou at the point I now had

reached.

I was in beautiful country. Beyond the bright gravel

beach, and points of fine white sand, of lake and river shore, rose

hills; gracefully rounded and sweeping in outline; massing large and

bold and grand. Along the shores where moisture wak plentiful were

willows, and a few alders, and small green tamarac trees; at their

roots, mosses, and much of that bushy ground-shrub known as. Labrador

Tea, the white bloom now dead, and rusty brown where unblown. Back from

the shore were hills grown mostly with scattered, low-statured Northern

Scrub Pine; the sand and gravel surfaces moss-covered, and the boulders

green as the surroundings, with lichen.

From time to time I went ashore to search for signs of

Caribou, climbing to bare, sandy, bouldered ridges in some cases, and

viewing range after range of like hills, with marsh and lake pockets in

the hollows in the foreground. . . . But never a sign of life in the

distance—there at my feet game paths worn down by the feet of countless

Caribou, antlers long cast aside, hair and bones where an animal had

died, markings of hundreds of rabbits (varying hare), but not a single

fresh footprint on the sand, except of fox and wolf.

Animal life seemed dead; not even a rabbit moved, and I

fear it must have been that minimum year of growth, that periodic time

when the rabbit plague nearly exterminates the species in a region.

Day after day I waited—and watched. . . . Everything in

the land had at first been beautiful, in my eyes—but, God ! how the

awful silence of its vast space grips you. Even now I felt it, even

before the great covering of snow had muffled every corner of the earth,

and land and water came to be bound in iron ice-grip.

At Fort Du Brochet I had been advised that I had not much

time to spare before freeze-up set in, and that I would be well advised

to return speedily. Later this turned out to be, for this particular

year, a deceptive estimate ; but, at the time, my waiting at the head of

the Cochrane River seemed precarious if I was to get out to the post

before ice formed on the lake, beach the canoe, and outfit for further

travel by dog-sled. Therefore, after two weeks of unrewarded watching

for Caribou, I gave up, and turned the canoe-bow into the south for the

first time for many months.

It was something over a hundred miles back down the

Cochrane River to Du Brochet Post. The return journey began favourably,

for the wind was behind, and wind and current sped the canoe merrily on

its way; but on the following day, and thereafter, the weather broke

down badly and rains and heavy head-winds delayed travelling. Indeed in

mid-afternoon on one occasion the storm grew so fierce that I gave up

struggling against it, and ran ashore and camped for the remainder of

the day.

It transpired that broken stormy weather had set in for

an extraordinarily long period, and on getting back to Reindeer Lake and

Fort Du Brochet, I had a long time to wait for freeze-up during an

extremely open Fall.

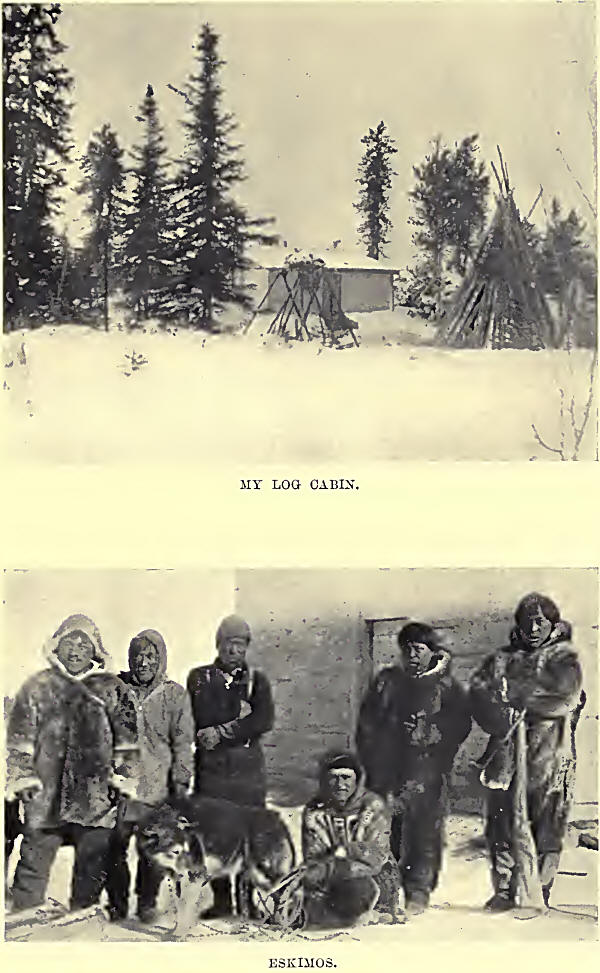

However, I had plenty to do while waiting, for, in

addition to collecting a dog-team from the Indians at the Post, I set

about building, on the margin of a small inland lake two miles north of

Du Brochet, a log cabin which was to be “my home” and 9 winter base, a

safe storage for museum specimens, and a quiet outlook from which

Caribou could be observed if in the neighbourhood.

To build a log cabin single-handed, and with only an axe,

is a substantial undertaking, and, though I was hardened with months of

“roughing it,” I found it arduous work. Standing trees had to be felled,

lobbed of their branches, and the heavy trunks carried from all

directions to the site of the cabin : afterwards the labour of

construction.

Working steadily from dawn till dusk, in three weeks my

“home” was finished—moss packed between the horizontal tree-trunk

cracks, and mud-plastered outside against penetrating wind and cold. If

you have lived long months in the open in all weathers, you will know,

when you reach habitation, the wonderful luxury and restfulness of

living with a roof overhead, a place for one’s belongings, and a

completely sheltered cook-fire; and when it is driving rain out-doors,

or blowing a wild old gale, or snowing pitilessly,

or freezing bitterly steel-cold, you may know what it is

to draw up to your glowing log-fire or lie snug in your deer-skin bag on

your branch-formed bed—if it be night—and feel altogether glad that you

have not to rise up and go out and do battle with the elements.

Meantime, in the northern latitude the seasons were

changing.

By mid-September the leaves of the birch trees had

completely faded to tints of yellow and yellow chrome, and many had

fallen. Summer birds had gone south, and their notes and cheepings were

gone from the woods which held but the chatter of an odd red squirrel or

the whistle of a friendly jay. Evening crept down earlier than hitherto.

Night after night Northern Lights be-ribboned the sky as they fleeted

across the zone from west to north-east (“The dance of the spirits,” the

Indians call this beautiful phenomenon); and always, now, when the wind

veered to the north it had the bitter chill of snow in it.

On September 16 there were snow showers; on the 24th

snow, and wind, and rain.

At the end of the month all leaves had fallen, and I

walked in a land of mourning, half-thinking to step light-footed lest I

disturbed the dead in a vast, deserted hall where even the evergreen

spruce and pine frowned down on me darkly.

Those were days of brooding grey skies—days of frost and

biting wind: days of repentance and thaw.

With October came freeze-up and snow, while Snow Buntings

were about the wood-bottoms and lake-shores, and passing on south in

migration. On October 2 the thermometer dropped sharply and all the

following day a snowstorm raged. . . . Winter had come.

Thereafter for many days land and water were binding in

iron ice-grip. Night after night the unspeakable silence of the great

snowland was broken by the awesome, re-echoing sound of rending ice as

frozen surfaces strained and contracted relentlessly, and split from end

to end in the all-powerful grip of zero weather. Repeatedly, nightly,

the eerie sound broke on the near shores to disturb a lone man’s

slumbers, and passed, with rise and fall of key, boom—boom —booming,

away into the level distance of the outer lake, to die in desolate

cryings.

By the end of October tliedand was in the grasp of deep

winter, which would rule for five to six months unremittingly.

But winter had been late in coming, for the Indians at

Fort Du Brochet say this was the most open Fall they had experienced in

the past eight years. Be that as it may—and I had come to be dubious of

all Indian records of time— winter had come, and with it the Caribou.

On November 4, late in the evening, an excited Indian

brought news that Caribou had been seen. They had been encountered,

north of Fort Du Brochet, coming from the east, and crossing the

Cochrane River. He told me, “Plenty deer; to-morrow we kill, and have

plenty meat.” “Would I go?” he asked, to my astonishment, while he drank

strong tea with me and smoked a pipe.

Now in my experience the Indians (I mean the unspoiled

Indians of the Far North) test a white man in their own peculiar way

before they accept or reject his friendship as good or bad, though they

do it so delicately that you may be unaware of their intentions.

Observant at all times, they are extraordinarily keen-sighted in reading

any mute sign of any phase of nature; and quickly read character in the

face, and in actions. I had come among those reticent Indians a

stranger, but ultimately I found that mine was a case that had extreme

advantages. Primarily I knew something of Wild Life after their own

manner, and could talk to them in their own way; which was generally to

illustrate a sentiment or a description through the medium of an object,

or a living animal, bird, plant, or element with which they were very

familiar. Indians are intensely reflective, and they have strange names

for wise members of their tribes which go to show this. I give a

translation of two of the best I have heard. “The silent snows are

falling, forming signs.” . . . “He listens to the unseen Rapids.”

Secondarily, I was not trapping fur, not, therefore, encroaching on the

rights to territory which were the red man’s by heritage. The research

work I did was full of interest to them. For hours I have had Indians

squat and watch me skin birds—a proceeding they had never witnessed

before— or skin an animal for remounting: which meant cutting the skin

so differently from that of a fur pelt, and the preservation of the

limb-bones and skull. Finally, but not the least noteworthy, if you have

a mind to humour Indians, on rare occasions I played a few ’pipe-marches

on a

Chanter, which astonished and delighted a people who are

passionately fond of music in any form.

How far those little incidents had gone toward making up

the approval and goodwill of the Indians I had had no inkling, nor had I

given the subject a thought until this day of Caribou arrival. But now I

had been asked to join them on the morrow, and go with them to this

secret place the Caribou were passing. I may be forgiven if I was

pleased at this certain sign of friendliness on the part of this

once-wonderful, fast-declining race of hunters, who speak mostly by

actions and rarely by words. Having a great admiration for the

intelligence and skill of the good old-world type of Indian—and they

still exist in the Far North—I confess I was glad to think that I was to

be one of such a party in their hunting; though I, later, was to learn

that the morrow held for me yet another Indian test— the last they ever

asked of me.

Thus it came about that in the small hours of the

following morning (3 a.m.) a guttural voice hailed me from outside my

cabin door and I drowsily extricated myself from out my fur sleeping-bag

to open the door and admit icy blast; and not one Indian, but the whole

hunting party—a total of seven. They had left the Post half an hour ago

and were on their way to the hunting-ground. ... I was to hurry, and

come with them.

By necessity in the northland one sleeps in most of one’s

clothing for warmth, for one had long left behind the land of wardrobes,

and blankets, and beds—and so in no time I was ready to join the others;

fur elad, as all the Indians were, in outer garment of Eskimo kind—a

pull-over, shirtlike, hooded upper garment, and trousers reaching below

the knee—all native-tanned Caribou hide with the long thick hair

outside. Oh our feet moccasins—that finest of, light footwear for fast

travelling and stealthy hunting.

I took down my rifle and we filed out of the cabin and

started off.

Outside the night-sky was dull and grey, but a fair light

was thrown on the snow by the cloud-obscured moon, which was full.

Led by Gewgewsh, one of the best and most active hunters

in the territory, the party trailed ahead in single file, at great speed

and without any seeming effort. With unerring knowledge of “lie” of

land, and every nature of obstacle to avoid, those Indians chose the

easiest and quickest line of travel to a definite objective ahead. As

they travelled one could hear the low tones of their hurried laughter

and guttural Speech, for excitement was intense among the Indians. They

were keen sportsmen, keen as children on an exciting game, and above all

they had been talking and dreaming of Caribou for weeks, and they knew

that to-day they would kill and have meat at last, and after a summer of

fish-food their palates, and the palates of their squaws and papooses,

were languishing for fresh meat.

About 5.30 a.m. the party reached a chain of small lakes

which it was necessary to cross; unmapped lakes that linked up with

Reindeer Lake further south. Those lakes had a strong current running

through them, and because of this current the Indians would not risk

crossing on the lake ice at present—a month later, yes ! Therefore the

party halted at a narrow neck between two lakes, through which open,

fast-flowing water passed. Here it was planned to cross by raft; and

speedily, with the faultless precision of men who knew exactly what they

wanted, some trees were felled and the construction of a raft begun.

Eight stout logs were cut and laid together over cross-poles at either

end and bound firmly in position. This done another tier of logs was

placed on top so that the total timbers would float the weight of a man.

The completed raft was about 2 ft. 6 in. x 9 ft. 6 in. Satisfied all was

then in readiness to go forward, and as time was not pressing, for it

was still night, everyone adjourned to the blazing fire which two of the

Indians had kindled, and partook of tea and food. How welcome was fire

and tea in the bitter cold morning to both Indian and White.

The picture about the fire was striking. A group of

fur-clad, gracefully athletic-looking Indians standing or squatting near

their firearms beneath the gloom of dark-boughed spruce forest which

night had not yet left; feather-flaked snow falling lightly, stippling

the air in its sustained, unhurried descent, and whitening the hooded

heads and shoulders of the men; inside the circle leaped the eager

flames of the log-fire, lightening the underside of the nearest

snow-laden spruce boughs, and casting a glowing touch of light on the

meditative, strong, bronze-dark faces of the Redskins.

Before long it was decided to move on. It was then close

upon dawn, which would be about 7 a.m., and clear daylight about 8 a.m.

The raft was carried to the water’s edge and floated on the stream, a

rope attached to it, and then Gewgewsh poled his way skilfully over to

the opposite shore. Once across he tied another rope to the raft; and

then, by see-saw method, it was pulled from shore to shore, each time

carrying from one side a single passenger, until all were across.

Once all were on the far bank conversation ceased and the

party moved quietly inland expectant of soon meeting Caribou. Coming,

after a time, to a small inland lake, the first indications of Caribou

were found—fresh hoof-marks on the smooth snow surface. Thereupon the

party changed its composition, Gewgewsh and another Indian going off in

a north-east direction to follow up the fresh tracks, while the main

party continued south-east. The two hunters had barely left us when we

heard them commence to shoot. Six shots they fired; one of which hit the

object, as was easy to infer by the odd sound of the dull plunk of the

bullet as it struck home. Soon the main party sighted Caribou—three

bucks on an open pine-wood hillside. Upon those a regular fusilade of

ineffective shots was fired by the excited Indians ; and then a general

rush to head them off, as they crossed running west, and more shots

during which one Caribou was brought down. The animal was cut and

disembowelled where it had fallen, and left unconcernedly to be gathered

later without an apparent glance to establish its location in forest

that I would have had to blaze a tree or two and take careful bearings

if I was to be sure of ever finding the spot again. The shooting of the

Indians—never brilliant—up to the present had been particularly bad.

They are, however, seen to better advantage when hunting more or less

alone, and when not unbalanced by over-eagerness to secure first blood;

as they this day were. Continuing, the party shortly afterwards again

dismembered; three of the Indians going off south-east, and the

remaining two and self heading now more south-west. We sighted two

Caribou standing in an open space, but they jumped off into the scrub so

hurriedly that it was impossible to shoot. About this time the two

Indians with me (the man who had asked me to come and another) appeared

anxious to go off by themselves. Until now I had been an interested

spectator, but not without inner excitement and inclination to try my

luck, so suspecting nothing, and assuming we would meet again at the

raft-crossing, I wished them good luck and struck into the forest alone.

I had gone no great distance before I came on three, or four, Caribou

feeding in low-lying scrub forest. Among them was a fine buck, and this

animal I succeeded in bringing -down, while the others vanished through

the timber. My quarry was not dead, but it was not difficult to track

him to where he had collapsed in a muskeg bottom a short distance away,

and dispatch him with a fatal shot.

It was then about 10 a.m. It was still snowing, but less

cold—not a bad day to stand about in; and as the Caribou was a fine

animal I decided that this was a good opportunity to secure a museum

specimen. Therefore I gave up further idea of hunting, got a good fire

going near the carcass, and set about comfortably skinning the animal. I

got through with my task sometime about 1 p.m., having then the head,

limb-bones, and skin complete. I then drank a refreshing brew of tea,

for one always carries a pan for that purpose, and prepared to go back

to the raft. I had brought my camera out, and food for another day :

this weight I discarded for the time and left beside the carcass of the

Caribou before I covered it over with a mass of spruce branches to

frighten off prowling animals, particularly timber-wolves. The raw hide

and limb bones and antlered head were then made into a pack and I

started for home from a place I had never seen before and that I had

entered with the guidance of Indians. Had it not been snowing my return

would have been arrived at simply by following back on my old tracks,

but these were covered an hour or two ago. However I had no doubt about

the main direction, and about 8 p.m. I was at the narrows. Not knowing

the country, I was at fault in meeting obstacles which I lost time in

getting round, and, indeed, finally reached the chain of lakes below the

narrows, having to work up-shore until I came to them. To my

astonishment, when I reached the narrows, I saw that the raft lay across

on the opposite shore. The Indians had gone home ! They had not waited

for me!

Not then, but later I learnt that they had done so to

know if they could trust me in bushcraft. It was a test—perhaps a stern

test—for think of it if I had been a tenderfoot, and lost, and out at

night in bitter cold; probably they did not even know if I had matches

to make fire : if one had not, God help him!

There was nothing for it now but to face the. crossing

and endure a cold plunge, so, with my pack held high, I waded into the

icy water, which I was glad, to find came no higher than my chest, and I

was. able to cross without swimming, which would have been an even more

unpleasant experience, with the current and heavy pack to deal with.

Thereafter I passed onward to my cabin at a hurried pace to keep up

circulation, so that my body and limbs would not be frozen. I reached my

destination about 5.30 p.m., shortly after dark—and none too soon, for

by that time the garments that had been under water were frozen stiff

and rasped awkwardly against my limbs, while alarming cold was getting

at my body.

Later in the evening I tramped through the woods into

Fort Du Brochet and the Indians were glad to see me. I noticed, though I

then knew not their purpose, that they exchanged furtive glances, but

made no remark that might infer that my appearance was other than

ordinary. [I may here say that from that day I went among the Indians,

and hunted and travelled with them, and knew I was henceforth accepted

as one of themselves, and was given a Chipewyan name which meant

“Caribou Antler”—a thing that was thin but hard and strong.]

At the Post the day’s experiences were recounted, and I

heard that the total Caribou killed numbered fifteen.

My observations of the day record: The wind was from the

south and the Caribou were travelling up-wind as is always their custom.

. . . Havens plentiful, following the Caribou. . . . Saw one fox, and

heard another barking in thiek timber.

Before daylight I was out again next morning back on my

tracks of yesterday to bring in the fresh meat of the animal I had

killed. At the narrows I took off my clothes before crossing and carried

them over on my head. It was bitterly cold while undressing and while in

the water, and I, was so frightfully numbed and Helpless by' the time I

was again dressed that I hastily Hindled a log fire and cowered

miserably over it until circulation returned. I had been foolish in

undressing, but heated with travelling the trail from the cabin to the

narrows I had underestimated the cold, and all but suffered frost-bite

for my folly. After careful travelling over the ground hunted over

yesterday, I got out to the neighbourhood of yesterday’s kill and soon

located my caehe, though snow had covered it since I had left, and it

was well I had blazed a tree or two for guidance. I thereupon made a

pack of my camera and as much meat as I could carry, and started

homewards again.

About midday I threw down my heavy pack, and made fire

for a meal on the margin of a small lake. It was a good place to see

Caribou if any were near, and before I was half through my meal I looked

up from my seat by the fire to see four animals trotting across the ice.

These I at once commenced to approach and succeeded in wounding a young

buck. When I came up to him he was not dead, but I thought he was

helpless, and was carelessly approaching him when, to my astonishment,

he rose and plunged at me. He had only antlers about the size of an

adult doe, and I managed to avoid them, though his side brushed heavily

against me as he passed. It was an action of despair, however, for the

poor brute went no distance before he collapsed again, and I despatched

him with a merciful bullet. I killed many Caribou later, but this is the

only case when I experienced one of those animals attempting to show

fight. It, however, bore out what the Indians had told me, for they said

such a thing sometimes happened. After returning to my fire and

finishing my meal, I cleaned my kill and left it lying, after covering

the carcass with spruce branches as before.

It is strange to you, no doubt, but true of one’s

ordinary habits in the North, that it was fully two weeks later ere I

trailed with dog-team to this lake, uncovered the cache and cut up the

frozen carcass with an axe to load it on the sled; then, moving on to

collect another hidden animal at another distant point, finally to carry

them back to my cabin for food for my huskies (sled-dogs).

However, to return to my pack : after caching the

Caribou, I loaded up and continued homeward. On the way I encountered

three more lots of Caribou but did not molest them. It is noteworthy

that the wind was from the north this day, and the Caribou seen were all

travelling north, up-wind, though it meant that they were going opposite

to the direction they had been travelling on the previous day. The big

lake (Reindeer Lake), which strong winds keep in motion after smaller

lakes are ice-bound, was not yet completely and solidly frozen up, and

the Caribou appeared to be feeding around the northeastern shores,

possibly waiting to get out to the extensive surface and reach the rich

feeding grounds on the countless islands. On the other hand the

direction of the wind seemed to have strong influence on their

movements.

Regarding pack-carrying, which I am reminded of by the

burden this day carried, I kept the meat load intact that I brought in,

which I had packed for five hours—possibly, in that time covering a

distance of some twelve miles—over hill and muskeg, and through snow;

and next day had it weighed at the Hudson Bay Post. It was 65 lbs. This

is a fair load—a load that strained me to carry it the prolonged

distance.

I am not physically a strong man, but I had been all

summer on the canoe trail and was hardened and inured to the toil of

portaging overland at bad rapids or inland to lakes. Judging things by

the weight of the above pack I would say an able Indian could

comfortably burden himself with 80 to 100 lbs. for a long distance. To

expect him to carry more, if he was in your service, would be unjust,

though I have found good Indians will attempt carrying excessive weights

rather than admit the smallest sign of weakness to a white man.

A pack load is a bundle bound firmly together after the

shape of a flour sack, and a half-circle of cord, or leather thong, is

formed into a carrying strap, so that when the pack is hoisted high on

one’s back between the shoulders, this cord is slipped over to the

forehead, and rests there, and thus sustains the load in position,

leaving the hands free to carry your rifle and assist in easing the

pressure of the load from time to time. The chief strain you will feel,

if you are unused to the pack trail, will be on the back of the neck,

for the weight of the load is heavily on your forehead and tends to

strain your head backward. Of course if your strap, or “tump-line,” is

of rope, a pad of cloth or grass will be placed between the rope and

your forehead to prevent its cutting into the flesh. A made leather tump-line

has a broad web where it passes across the forehead.

Those experiences I have recorded are similar to many

that followed during the winter, too numerous to describe in detail.

In time I had secured, for museum purposes, handsome

specimens of the Barren-ground Caribou in winter coat—an adult male, an

adult female, and a yearling fawn (male).

To give an idea of the size of these animals, the male

measured forty-eight inches from hoofs to the highest part of back (the

haunch), the female forty-two inches, and the fawn thirty-seven inches.

In colour the winter coat of the male is: Back, sides, legs, and head,

medium dark umber-brown; fore-shoulders, and entire neck, above and

below, dull white; tail shows white when erected, as it most often is

(it is, however, brown on the4 upper side) ; breast and belly are brown

like upper parts, but turning to white toward roar, between hind legs. A

grey strip (a mingling of the white and the brown hairs) runs

horizontally along the middle sides from the white of the shoulders to

within eight inches of the hind-quarters; ears and upper forehead, grey.

The adult female is, generally, much lighter in colour than the male;

rear of back, legs, and nose were in this specimen the only parts brown;

middle sides, hind-quarters, lower limbs, forehead, and ears, greyish;

remainder, white. The fawn was very similar in colour to the female.

Both male and female have antlers, the males having a great backward,

outward-curving length; the females short and symmetrical like those of

a young buck. In early winter some of the bucks still carry antlers, but

the greater number of animals have cast them at that time.

They are graceful animals, particularly graceful when

they are in alert motion, and carry fine suggestion of indomitable

pride. They trot with easy, swinging, far-reaching strides, with

movement lithe and Inuscular. The forefeet are flung high with

sharp-angled knee action (like a well-broken hackney), while the hind

legs stretch well back before they thrust the body forward. Caribou

sometimes start off, if frightened suddenly, by rearing in the air with

a powerful spring of the hind legs.

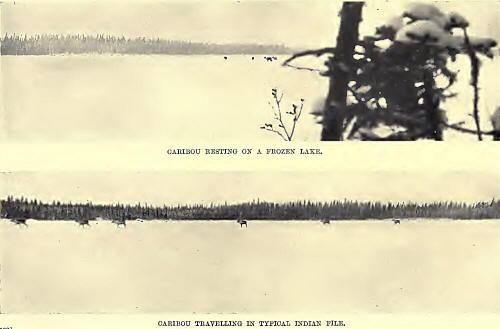

The track of Caribou on snow is a line of single

hoof-prints running out one point directly in front of the other—not any

two hoofs together—not any hoof-print on the left side or right side. A

typical measurement of the span between hoof-prints is twenty-five

inches, from front of one hoof to rear of the next in front; an ordinary

hoof-mark measures four-and-a-half inches by seven-and-a-quarter inches.

The above of course refers to the track of a single animal. Caribou are

much given to follow in Indian-file one after the other, and soon tread

down a regular path of footprints in the snow.

During the next two months I travelled through regions

that were wrapped in resolute Arctic winter, vast regions formidably

hushed, incalculably desolate; more completely impoverished of life and

activity than any words can depict. One moved in a soundless land, a

land that was deaf and dumb and had no organ of expression; and one

could understand, while living in this place of dead, why men go mad

under the awful shadow of utter loneliness, and under the unspoken,

fanciful questioning which unmitigated space will prompt and throw back

unanswered, touched with a sense of discouraging mockery. In many places

there are not even Caribou; not one single moving object in a day’s

trail over dreary, snowfields. In such regions, in deep winter when the

thermometer is anything from ten to sixty degrees below zero, one’s

salvation is companionship. At such a time I have learned that it is

folly to go beyond the last outpost without a comrade, even if that

comrade only be an Indian—and there is no finer, more unselfish comrade

on a hard trail than just an Indian. Starvation, sickness, frostbite,

madness: any of those might carry one “across the line” in but an hour

or two if one was stricken when out alone in the all-forsaken land of

merciless cold.

However, to return to the Caribou and the main object of

this narrative, during my winter travels I was fortunate to see

thousands upon thousands of those graeeful animals.

Once in particular I witnessed the purposeful migration

of Caribou. This was when returning in December, short of food and short

of sled-dogs, from the region of the Barren Lands, where no Caribou had

been seen. Indeed, not one animal was encountered north of the locality

I speak of, a point about sixty miles north of Reindeer Lake. Here one

morning, after camping overnight on the edge of a small lake that only

had a range of view of about a mile, from daylight until I struck camp

about 11 a.m., I witnessed countless herds of Caribou crossing the lake

in a south-easterly direction—one herd following another, company on

company, regiment on regiment: and they were still passing when I left.

It would be impossible to estimate them. One could not tell where the

column began nor where it ended, nor if similar columns were passing

behind us to the north or beyond vision in the south. I attempted to

count some herds as they crossed; one numbered close on one hundred

before it disappeared into the forest and I could count no further. Many

were bands of between twenty and forty. All appeared intent on

travelling, and were, as far as one could see, all does and fawns. The

Indians assert that the does and fawns are now moving north again

(December 20), and say that this is about their usual time for doing so.

However, the migration I witnessed was going south-east, as I have said,

though I cannot deny that if the wind veered to the north they would

almost certainly swing in that direction. I have come to the conclusion

that they always travel up-wind, and that they only gain distance in

whatever determined direction they are travelling by going forward more

rapidly in a favourable head-wind, and returned more slowly on an

adverse head-wind. It appears to me something like incoming tide on the

seashore ; waves washing forward and drawing back, but ever reaching

further and further up the beach to the distance they are set to gain. I

believe the strongest motive the animals have in travelling up-wind is a

very simple one, that of comfort and warmth (as a seabird riding the

waves), since the wind then blows the way the hair lies on the animals.

A further motive is that in thus travelling they are assured that their

keen scent will warn them if they are approaching danger.

Caribou I also conclude are rather an elusive quantity.

They may be here to-day and gone to-morrow, and not an animal may be

seen in a certain locality for a week or two weeks. Then one day you may

find they have returned—or is it a fresh lot arrived ? In December there

were no tracks or signs of Caribou north of latitude 59°. Southwards,

between latitudes 58° and 59°, the great herds above mentioned were

encountered. Yet when I got into Du Brochet Post again (a little south

of latitude 58°) the Indians complained of the Caribou being very

scarce, and all were anxious about /neat. In January I travelled south

on the great sea-like area of ice-bound Reindeer Lake. At that time

Caribou were plentiful on the lake except toward the south end, where

there were few, and the people at. the Hudson Ray Post then had very

little meat. Possibly Caribou came down after I left, for -I believed

the bucks to be still working south.

However, the Indians tell me that when the Caribou fail

to pass their neighbourhood as they have been accustomed to doing, they

are sometimes forced to travel and camp in a favoured locality so that

they may kill their winter store of meat and not starve.

Whenever I had the opportunity I closely questioned

Indians regarding the numbers of the Barren-ground Caribou, and every

individual was agreed that in the neighbourhood of Reindeer Lake and in

the territory north of it, those animals were more plentiful in 1914

than in former days. There is one factor which perhaps accounts largely

for this increase of Caribou, and that is that the Chipewyan Indians who

inhabit the territory directly south of the Eskimo country, and who are

called in their own language “The Caribou Eaters,” are fast dying out,

victims of interbreeding and consumption. It is sad, but woefully true.

Philip Merasty, an old half breed, 61 years of age, who, when a child,

came with his people from lie h la Crosse to camp at the north end of

Reindeer Lake, whence plentiful Caribou meat had drawn them, told me

that when he came there were then three hundred Chipewyans in the Du

Brochet territory, and in 1914 they numbered less than one hundred. If

one estimates the Caribou kill, per male Indian per winter, at about

forty animals (which is a common average in my experience, though it

exceeds by double the number Thompson Seton estimates in his book The

Arctic Prairies) and takes the adult male population as about one third

of the whole population, one arrives at substantial figures which show,

in a broad sense, how much less destruction is taking place among the

Caribou at the present time owing to the decrease in Indian population.

I arrive at figures in this way: If in 1864 100 Chipewyans killed 40

Caribou per head the total kill was 4,000 Caribou, and if in 1914 34

Chipewyans killed 40 Caribou per head, the total kill was 1,360.

Therefore, at a broad estimate, 2,640 fewer were killed in that area in

1914 than fifty years ago; and each year the conditions are

improving—for the Caribou. Moreover, the territory I speak of is at

present far beyond the reach of the white hunter, and is likely to

remain so at least for another century, so that there is no. incoming

race to counterbalance the outgoing Indian.

When first encountered the Caribou were feeding on

withered marsh-hay, growing sometimes with tufts still above the snow,

along the edges of the countless land-locked lakes; and on moss of a

pale greenish-white colour which grows on sandy hills, or more

luxuriantly in low-lying muskegs. Later they fed on similar food, but

had to dig through the snow for it—as I have previously described. In

bad snowstorms the Indians say the Caribou yard together after

the manner of frightened sheep, and that a man can walk in among them at

such times; but this I have not witnessed. The Caribou invariably feed

up-wind, as I have said, and travel overland through the woods from lake

to lake along chosen paths long established. It is common about noon,

when the animals are resting after their morning feed, to find Caribou

out in the centre of a lake, lying down or grouped about resting in the

sunlight, while the watchful old leader scans the open snows-on all

sides, and sniffs the drifting wind.

If you have found Caribou country in winter, and can put

up with intense cold, you will find that the actual shooting of these

animals is not difficult. They are stupid animals once you have

frightened them with a shot, and if you get within reasonable range of a

band on a lake you are certain to bag more than one of them, if you are

anxious to secure meat or particular trophies, for if you bring down one

with your first shot, and run on when they run, the others will almost

certainly halt before they have gone far to look back for their comrade

or to make certain where danger lies, and you will have opportunity for

further shots. To give an instance of this : on one occasion a band of

twelve Caribou came on to the lake where my cabin stood. This was

bringing dog-feed to my very door if I could effect a kill—and the

distance you have to carry meat from the point you kill to your camp is

no inconsiderable detail if time and labour and sled-dogs are to be

saved. Therefore I snatched up my rifle and a handful of cartridges and

eagerly gave chase. Before long, by hard running and quick shooting, I

had six carcasses lying one beyond the other in wake of the confused

sheep-silly band, before the Caribou got into the forest at the north

end of the lake; and if cartridges had not given out I believe very few

would have got away. This illustrates what I have said, and what I have

often experienced, for each time I fired the band started away, and I

after them, until they made that fatal halt to look back, when I would

halt also, and pause to fire again— and so on, with the above result.

The best range at which to shoot Caribou is, in my

experience, inside one hundred yards, and to shoot to kill the animal

with a clean shot, for a wounded animal, badly hit, that gets away, is

not pleasant to think of, especially as one may know that the poor

animal will freeze to death once it ceases travelling. Again, a wounded

animal that you might follow may take you miles off the course you

happen to be travelling, and through overgrown country that you cannot

afterwards take a dog-sled into, to gather the meat, in the event of

your killing the wounded animal.

I have killed animals outright with *303 Ross rifle at

312 paces, and 447 paces, when I had no alternative, but, irrespective

of marksmanship, those distances are too great to make certain of clean

kills. Shooting in intense cold, unless you have a special-fingered

glove and can shoot with it on, you will almost certainly get the

fingers of your right hand frozen, if you fire more than one or two

shots in succession with the bared hand which you have taken from the

heavily lined deerskin mitten. I’ve had all the fingers of my shooting

hand frozen, sometimes down to the second joint, but if attended to at

once and thoroughly chafed with snow there are no serious

consequences—nothing but the sharp pain of reviving circulation, and,

sometimes, the skin will afterwards blacken and peel off.

I turn now to the Indians, and the extent of their

Caribou hunting. It has been said that Indians kill less with modern

weapons than they did in the past by primitive methods, but I think such

a statement should be taken with reservation. I grant that Indians, as a

rule, are indifferent marksmen, but it is well to remember that what

they lack in that respect they more than make up for in bushcraft. They

are undoubtedly skilled hunters, keenly intelligent hunters with

a second sense—a wild sense which is essentially Indian and which makes

it possible for them to get very close to animals, much in the crafty,

patient manner of prowling wolf or fox that manoeuvre to outwit and come

within striking distance of their prey.

On October 21, 1913, an Indian of Fort Du Brochet was

returning after dark on the lee of Reindeer Lake, after setting out a

trap-line, when he heard the muffled thunder of countless Caribou

passing north-east over the ice. No Caribou had been seen until then. It

was the hour of their coming. This Indian got back to the Post in great

excitement and soon spread the glad news among the half-dozen cabins on

the lake shore. The following morning at the first faint light of dawn,

the hunters of the settlement went out to kill, while the Caribou

continued to pass all day over the same route which herds had been

tramping over all night—a route which was in full view of the Post when

day broke. During the hunt that followed two Indians killed sixty

Caribou, and three others, forty-four Caribou: a total of one hundred

and four Caribou to five rifles. This was a good kill, for the

conditions were perfect, since the Caribou had been found in the full

flood of their migration, and no distance from camp. And is it not a

better bag than five men would obtain by snare, and spear, and

muzzle-loading gun, in primitive hunting? for, as I describe below, it

apparently took a much greater number of men to effect any like large

capture in the past.

The method of killing Caribou in numbers in the past, in

the territory immediately south of the Barren Lands, I here recount as

more than one veteran Indian has described it to me: In olden days

Caribou were largely caught in snares. The Chipewyan tribe in the whole

neighbourhood combined in one grand hunt at the season of the Caribou

migration. It was their custom to select a locality in the forest which

they knew to be much favoured by Caribou, and there set snares, made of

stout “babiche” (leather thong), by hanging them, at a height to form a

head noose, between stout trees wherever old Caribou paths passed. They

would set a hundred or more snares in this manner before The Trap was

complete; whereupon the hunters who were armed with spears and

muzzle-loaders took up their positions so as to watch the trap and

encircle it when the Caribou approached. Thereafter they set themselves

to wait and watch for the approaching herds, and sometimes they had to

keep vigil for days. When Caribou came a large number were allowed to

pass inside the watching cordon of Indians, who then formed a wide ring

and commenced to humour them onward into the way of the snares. When the

animals were fairly entrapped the Indians would close in from all sides,

driving the Caribou to their doom, and shooting them down or spearing

those that tried to escape. Sometimes none of the herd escaped (asserted

to be as many as two hundred in some instances), all falling prey to the

Indians’ skill and active watchfulness. If one bears in mind the

sheep-like tendency of Caribou to lose their heads when thoroughly

alarmed, it will be understood better how hunting in this manner was

practicable to men with endless resource in bushcraft.

Caribou, which are strong swimmers, are also killed in

numbers when swimming lakes in their early Fall migration. Some Indians

on the borders of the Barren Lands make kills in that way, but they are

principally made in the Eskimo country, where the Eskimos, in their

frail, active-moving kayaks, surround a herd of animals in the water and

spear them to death.

Having cited those large kills of Caribou, past and

present, I might be asked, Why such wasteful destruction? In answer, my

experience bids me defend the Indians, for of all the Caribou I have

seen shot by Indians (no inconsiderable number) I have never known of

one being wasted. In the first place it is wall to remember that the

Chipewyans look on the Caribou as a thing sent solely to them by [The

Spirit, to feed and clothe them through winter. Caribou are essential to

the existence of those people, for the Chipewyans depend largely, almost

completely, on them for winter food, though otherwise absolute poverty

is relieved by limited stores of frozen fish, and what few fish are

netted below the ice. If one hears complaints at all, it is that not

enough Caribou can be found : never that they have too many and would

leave some to waste. There is greater use for large quantities of meat

than one, at first thought, might imagine. Indians are voracious eaters

at all times, particularly in the intense cold winter weather, and they

eat Caribou meat extravagantly when they have it, and eating it, and it

solely, three or four times a day, as they often do, a single animal is

soon devoured. Then, too, and this is the chief factor to be borne in

mind, Caribou are extensively used for dog-feed whenever procurable in

numbers. If an Indian has ten sled-dogs to feed, one carcass cut into

portions will barely feed them for three nights; the number of dogs is

more often twenty, sometimes thirty or more, and the call on the

food-supply accordingly greater. So it will be seen that, though Indians

kill large numbers of Caribou, they have a definite need for them in a

land where food is not bought; where red men wrest a livelihood from

rivers and lake-waters, virgin wildernesses, and dreary snow-wastes; and

where to be without food is to die.

It is hardly necessary to say that the flesh of the

Caribou is splendid food. The choice parts the Indians select, when

opportunity occurs, are the tongue, the heart, the kidneys, the brisket,

all fat, and the limb-bones (after most of the meat has been removed)

for the marrow therein. The tongue is undoubtedly the choicest part of

all, and a delicious delicacy. In past days the Hudson Bay Company

annually sent out from Du Broehet Post many tongues and barrels of

Caribou fat which were greatly prized by the factors farther south.

Indians, as I have already said elsewhere, have an

observant and very intelligent knowledge of wild life. This is borne out

in the Cliipewyan manner of speaking of Caribou, when hunting them. They

will not say, “There is a caribou,” but will use a name which describes

its individuality as well, since they have a series of names whieh

discriminate at once the condition, or age, or sex, of the animals they

encounter. Thus names mean: “a fat Caribou,” “Caribou in poor

condition,” “a Caribou doe in fawn,” “a young fawn,” “a yearling

Caribou,” “a three-year-old Caribou,” “a five-year-old Caribou,” “a doe

Caribou,” “a buck Caribou”—and so on.

As well as providing the Chipewyans with great stores of

winter food the Caribou supplies them with skins for clothing. In the

past, Caribou skins furnished them with all their material for clothing

and the covering for their teepees. Now, when they can, they get white

man’s clothing, and canvas for their teepees, in fur-barter with the

Hudson Bay Company and Revillion Brothers—a change which is decaying

native skill and native beauty. There are still, however, smoked

Caribou-skin teepees in use, while winter fur clothing, and moccasins

made from Caribou hides, are universally worn. Summer clothing—-top-boot

leggings and shirts, made from flexible native-tanned skins, are now

entirely out of use.

Caribou-skin products are prepared by the Chipewyans as

follows:

Babiche.—Long lengths of tough leather lace, or thong,

made from raw hide. Process of preparation: hair scraped from skin; skin

dried; then skin soaked till soft, and cut into long strips by circular

cutting. Skin in nowise prepared by the lengthy process required when

dressing skins for moccasins, etc.

Skins dressed as Soft Leather.—Lengthy process requiring,

chiefly, industrious hand-working. Skins soaked, and dried in the open

air, and worked with hands; process repeated many times, each time

becoming more soft and more white. When lying out, the clear, fresh air

purifies the skins, as in ordinary bleaching. Skins finally soaked and

rubbed in a solution of Caribou-brain (in the absence of brain ordinary

soap is used): brain contains grease, which has the essential softening

quality. The skins, when finished, are very soft and flexible like

Chamois leather, and are, particularly if they be fawn skins, often pure

white.

Dressed Fur Skins.—Hide dried first by stretching on the

circular inside of teepee—thus drying by the heat of the fire alight on

the ground in the centre of the interior; skin then rubbed with brain

(or soap) and worked clean of all flesh, fat, etc.; a little water is

applied during process of rubbing, but skin never allowed to become very

moist. Inside skin soft and flexible when finished, and the outside

hairs, untouched.

Caribou-hide is best (thickest) in spring, and no good in

mid-winter (being then thin). The hair, apparently, feeds on, and

derives nutriment from the skin, for when the hair is long in winter the

skin is thin, and in the spring when the hair is new and short, the skin

is thick and at its best.

Before leaving this subject I will endeavour to tell of a

few experiences of photographing Caribou: experiences that were not very

successful, because of the action of intense cold on the focal-plane

shutter, but which give considerable detail of Caribou habits and winter

hunting.

It was with old Philip Merasty, a half breed, and

Eaglefoot, a Chipewyan, that I made my most determined attempt to

photograph Caribou; and the last attempt I made, since cold and

unsuitable apparatus completely baulked me from further effort.

Philip, without knowing it, was, like many an Indian, an

unread wilderness naturalist. The clouds, the water, the fish, the

land—the forests, the birds, the animals—all in his country he had

studied for a lifetime, and, at ripe old age, he was full of wisdom of

the wild. He had watched me skin and label specimens, watched my

manoeuvres to take wild-life photographs, watched my making pencil

sketches; and in time had proved himself a staunch confederate in

assisting my researches.

Eaglefoot, perhaps, had equal knowledge, but h§ was

silent, almost, as the snow. Half a dozen words with Philip in the

morning would decide a day’s plans, and half a dozen sentences over the

camp-fire at night record all the day had accomplished. But he was a

splendid hunter and traveller, and a hard worker if there was work to

do.

Neither of those Indians had ever seen a camera before

they saw this one of mine, and to allow them to look through the

view-finder or focusing screen afforded them great astonishment and

delight, when they beheld the miniature pictures in the glass. It seemed

to them witchcraft. They expressed the same excited astonishment in

looking through field-glasses.

With those two Indians, and food, sleeping bags, and two

dog-trains, we one day set out from my cabin to travel and camp on

Caribou ground. And the days that followed I here record from the simple

pages of my diary—written at the glowing log-fire o’ nights, where

comfort was before one, and cruel, hungry cold a yard beyond the camp

circle. . . .

Philip and Eaglefoot outside my cabin at

daylight (8 o’clock). I joined them in a moment, and we sped merrily

away in a northerly direction over well-packed lake surface: the dogs

fresh, and the sled-bells tinkling cheerfully.

Soon after starting Philip looked gravely into the

even-toned, grey sky and prophesied that wind would rise, while to me

the sky in that phase was unreadable. In a few hours wind did rise— keen

north wind.

On the trail outward Philip looked at his trap-line;

traps set for Fox, Marten, and Mink, but none contained quarry. I came

on a few Spruce Grouse, while halted, and while Philip was examining a

Fox set, I, to Eaglefoot’s astonishment, shot one with my catapult. He

had never seen my “noiseless gun” before, and picked up the dead bird to

examine it and reassure himself that I really had struck it to death.

Proceeding we travelled north up a long inlet bay to the

north-east of Fort Du Brochet, thence over one long portage, and then

through four small lakes and on to a big irregularly shaped lake named

Sand Lake.

At first fire the sled-bells were removed from the

dog-harness, for they are never used when serious hunting begins;

obviously because of the sound.

Soon after first fire (three hours out—the first rest for

dogs, and fire for a drink of hot tea), on entering Sand Lake, twelve

Caribou were sighted, but they were, a moment later, disturbed by an

Indian, who appeared ahead and gave chase. Before long, however, they

doubled back towards our party, and Philip shot once without effect.

When nearing the end of the north bay of this lake, about forty Caribou

were sighted. At once the dogs were run into forest ambush, and we

waited in hiding for the oncoming animals. Ultimately I succeeded in

making four exposures of a few of those Caribou, but the main herd went

away north-east. When there was no longer prospect of obtaining further

photographs of this lot, Philip and Eaglefoot fired on them at long

range, but neither brought any down. A little later a young buck, which

had become separated from the main herd, came back past us, and this I

shot for the night’s dog-feed.

At the narrows between Sand Lake and the nameless lake

beyond it, Philip and Eaglefoot chose a base camp, and the sleds were

run into cover on a well-timbered low point of land. We were in good

Caribou country, and it was intended to spend some time here and prepare

unobtrusively to influence the direction of Caribou travel, so that they

might come to pass before the camera.

Our procedure was this : to cut from the forest on the

shores armfuls of spruce boughs and lay them, at widely spaced

intervals, on the white lake surface of the upper lake to form a thin

boundary line. This fence was laid after the tracks on the forested

shores had been examined, and the wind considered, and Philip and

Eaglefoot had decided that Caribou would possibly come from the west on

the morrow. Where Caribou were expected to come on to the lake from the

forest a few boughs were placed very close to shore, so that when our

quarry stepped on to the lake the strange objects would not be observed

until the animals looked back or tried to return by the path they had

come. As will be seen shortly, Caribou will not pass near any

suspicious-looking object. Along both shores the fence was carried out,

making short cuts across the bays; and after the shores were laid the

slim enclosure was completed by running a line of boughs from shore to

shore across the centre of the lake.

There then remained open, to any animal that might enter

the enclosure, only the narrows leading into Sand Lake, where I and the

camera would be hidden.

It was night when we had finished and returned to camp.

Camp was made snug against the keen wind and bitter frost by building

the usual barricade of spruce boughs and snow in a half circle, backing

the wind; and within the circle, just beyond the length of an

outstretched man, a great log-fire was built to blaze merrily (and to

die out long after the fur-blanketed forms had gone to sleep). All the

ten sled-dogs were tied up this night—an unusual proceeding—to keep them

from wandering to the traps on Philip’s line, and from chasing any

Caribou that they might scent in the night. They were then given the

whole of the Caribou that had been killed, and twenty fish—a repast

intended to keep them drowsily contented and quiet on the morrow.

The following morning we were moving about camp before

daylight, preparing in earnest for deer-stalking. Any of the dogs that

showed inclination to howl or whimper was securely muzzled with rope:

the morning fire burned low: the ordinary quiet voices of the Indians

sank to hushed whisperings—those precautions even although our camp was

well back from the shore and in the shelter of forest where there was

but slight likelihood of smoke or sound reaching the senses of any

animals that might approach.

A hide for the camera and myself was built of spruce

boughs on the outskirts of the point of land, and commanding the lake at

the entrance to the narrows where the Caribou were expected to pass. The

hide was built as small and insignificant as possible, and the

outside—that which might be apparent from the lake—was sprayed with snow

until it resembled the natural surroundings. The first two hours of

daylight passed uneventfully, and it was not until about 10 a.m. that

two Caribou were sighted. These animals came on to the ice south of the

narrows —they had come off the shore past the camera —but the cunning

Indians had foreseen the possibility of this, and a few spruce boughs

barred the narrows, some distance beyond my outlook. At this fence the

two Caribou were turned, and after a long wait they began to approach

the hide. Of the leading buck I obtained one good exposure, and though

slight was the click of the release the animal heard it, and swung round

as if he had been shot at: there he paused for a second, proud head up

and great eyes alarmed, while I remained motionless; but in a moment

more he turned and retraced his steps, smelling the ground suspiciously,

while his companion followed.

After this there was a long period of patient waiting—not

an easy matter in the numbing cold—and it was noon when the next Caribou

were seen. It was then that a small herd of a dozen came on to the lake,

and within the enclosure, from the west shore. They were very nervous,

probably because of the “fence,” and they made one or two short rushes

as if they meant to risk galloping through the barrier that lay across

the lake—only to come to a halt in the end, and to look about

wonderingly. The wind was from the north, hence their inclination was to

get beyond the fence across the lake, but each time they “funked”

crossing between those harmless bits of spruce. Twice the buck that was

the leader came half the distance forward to the narrows only to turn

back again to the northwest, and mingle with the others in frightened

bewilderment. Finally the buck made up his mind, and came for the

narrows at a long-reaching trot, neck outstretched, head up and horns

lying back over the shoulders. Without a halt he came right on, and I

allowed him to pass unmolested—he was well ahead of the others— then

made some exposures of the following line of does and fawns that filed

past the hide. They were fine fat deer, Philip decided, after they were

past—he had, in his keenness, come quietly beside me to watch also—and

he ran back to camp for my rifle to shoot at them, but luckily they were

gone ere he returned and he couldn’t spoil, by the noise of shooting,

what chance there might be of other animals approaching. However, it was

then getting late, and the light was failing, and we were on the point

of leaving off for the day, when Philip, who had been moving around the

shore a little way, came to tell me that a single fawn was approaching.

This animal walked all along the fence, smelling the ground where the

others had previously passed, and uncertain where to go. Finally it got

on the fresh track leading to the narrows and came ahead quickly. As the

animal passed I made two exposures, though the light was by then very

poor. A little beyond me Eaglefoot dropped the poor brute, for food was

wanted for the dogs; but one felt one would have been glad if it could

have run on, and found the herd it had strayed from. It paid the full

penalty for loitering behind.

It was now 3 p.m. and too dark for further camera work.

It had been snowing lightly all day, and the light was not very good for

making rapid exposures. However, what was really worrying me was the

action of the intense frost on the focal-plane shutter. Twice it had

absolutely stuck in the middle of an exposure, and twice, also, it had

refused to act at all when beautiful Caribou pictures were possible. I

was beginning to fear the shutter was going to spoil everything, and

that I wanted a very simple instrument to replace this complicated

mechanism, to which tiny frost particles clung and jammed the finer

workings. Over the evening camp-fire I spent an hour trying to prevent

any recurrence of a hitch in the shutter-workings. Before the heat of

the fire it worked perfectly, and I laid it aside in the end with

renewed hopes for the morrow.

The early hours of night were employed cutting wood,

feeding the sled-dogs, and cooking a large meal of Caribou meat. Then we

lay for an hour or two before turning in, the meditative Indians

smoking, and from time to time piling fresh logs on the huge fire. Over

the fire, in the upper flames, hung the ghost-like, blackened head of a

Caribou, spiked on to a long green staff that was stuck back in the snow

to hold the head up in position—and this was the manner of roasting our

final tit-bit before going to sleep for the night. They are glorious,

those night fires of a winter camp, not only warmth and light, but

cheerful withal—the home-fire of the trail, where there is real content

in the mind of the wayfarer as he watches the flames that incessantly

shoot upward in bright spiral lines to wriggle like snakes into space or

snap into tiny floating sparks which die out in the blackness and

chillness of the surrounding night.

It snowed heavily overnight, and we awoke in the morning

to thrust our heads through the foot of snow that covered us in our

sleeping bags: the thermometer had dropped also overnight; and

altogether it was in no way pleasant in camp before we got a roaring

fire kindled. Fire and tea and breakfast soon warmed us up; and about

daylight the sky cleared, and the snow, while a strong biting north wind

sprung up.

At breakfast I amused and interested Philip in telling

him of a strange dream I had had in the night. It was this: He (Philip)

was driving his dog-team in a strange foreign country, when, while he

stopped to shoot at something, his dogs ran away with the driverless

sled, and it was finally seen careering through the streets of a great

city. At this time, by arrangement of the strange freak settings with

which dreams are embodied, Eaglefoot and I were coming along a side

street in the same strange city when we saw Philip’s dog-team tearing

past on the main street like animals possessed. Both of us gave chase.

At a corner, where the sled slewed awkwardly, some bales and blankets

were thrown out, and with those the exhausted Eaglefoot remained while I

careered on. Finally I caught the dogs, but when I came to drive them

they would not go. The difficulty—in the dream— seemed to be all because

I could not recall the name of Philip’s lead-dog. Think as I might I

could not recall it. Meantime crowds had collected who had never seen a

sled and dog-train before. They were strange, tall, delicate people who

spoke no words I could understand. In the end I led the dogs back to

where Eaglefoot waited, and was again loading up the bales and blankets

so that we might go in search of Philip—when I awoke . . . and my first

conscious thought was intensely concentrated on Musquaw—the name of

Philip’s lead-dog. The old Indian was intensely interested in this yarn.

In many ways Indians have the naive receptive intellect of children.

But, to return to the 'work of the day. The drifting snow

on the lake had, when we looked out from our hide after breakfast,

partly covered the spruce boughs of the “deer fence,” and our first task

was to travel round them all, lifting them, shaking them, and replacing

them. After this we had a very long wait before any Caribou came,

probably because our movements around the “fence” had frightened any

that chanced to be in the immediate neighbourhood at the time. However,

about noon, a single male Caribou came slowly on to the lake from the

forest on the west shore, and then, apparently surprised, stood long,

watchfully alert. Philip, who was with me at the camera, remarked in a

whisper, “Him not alone, that’s why he wait,” and sure enough a little

later a doe and fawn followed out of the forest, whereupon the buck lay

down to rest on the lake surface. But when the others joined him they

walked around uncertainly, not seeming to find the resting place

comfortable, and so, in a little time, the buck rose and led on across

the lake to the east shore, where all lay down in content. They were

now, however, too comfortable for my liking, for after more than an

hour’s wait at the camera hide, the animals still showed no inclination

to move. At last it was decided that Philip should make a wide detour

through the timber on the east shore with a view to getting beyond the

Caribou, and disturb and drive them toward the narrows. When Philip got

round into position (he afterwards gave me the details of his movements)

he snapped a small dry twig. Instantly the buck’s head, which had been

resting turned in toward the body, flashed sharply upright, and he

looked steadfastly in the direction from whence the sound had emanated.

Again Philip snapped a twig, and at this the buck rose and faced the

sound, then fully satisfied that danger lurked in the wood he

half-turned and commenced to trot in my direction. Soon the others rose

also and followed, but not before the buck was well away in the lead.

The buck passed very close to the camera, and I

repeatedly tried to make exposures, but, alas! the shutter was frosted

and refused to work. Then followed the doe and fawn, and renewed

heartbreaking failure on the part of the camera, while the unalarmed

animals even approached the hide to investigate the click of the shutter

release, a sound which was apparently curious to them.

This was the end of patience. What use to continue? It

needed no further trial to teach me that my focal plane shutter was

useless in the intense cold. For the time I must give up. If I lived to

return in other years I would know what to bring to overcome the cold.

So the dogs were harnessed into their traces, and we

prepared to leave for Reindeer Lake. But before vacating camp the wily

Philip set two traps—one for Marten at the foot of a tree, and one for

Fox at the remains of a Caribou carcass. The observant old native had

seen Marten tracks on the snow near camp, and be told me "he come seek

about camp after we go, that’s their way.”

About 3.30, when dusk was falling, we led the dogs from

the forest to the lake and, muffled in our robes, started grimly