|

Without sled-dogs there could be no winter travel over

the great territories of the Far Canadian North, and consequently little

or no fur trade. Possibly you have never had occasion to think of such a

modern thing as commerce in connection with those great snow-bound

wildernesses that lie beyond the white man’s country: possibly it never

occurred to you that the winter life of Indian and Eskimo could concern

you in any way at all. Yet, since to them do we owe thanks for great

stores of fur pelts, they touch on our lives in an indirect way even as

far "back home” as London, Paris, New York, and in all cities; though

few people who buy rich furs over city shop counters picture the drear

surroundings in which fur-bearing animals are captured—interminable

wastes of snow; intense cold, even blizzard; and lone men with patient

wolf-dogs battling against bitter, merciless Arctic winter. Perhaps only

Vikings of the ancient Hudson Bay Company, and others of the like who

have traded in fur for half a century, really know how much is yearly

harvested by the aid of the sled-dog. Just as civilisation cannot to-day

do without railways, so the Far North cannot subsist in winter without

dog-trains; dogs which are the means of gathering from great distances,

and long trap-lines, the choicest furs for the markets of civilisation;

and that gather also the fuel-wood and winter food that keep alive the

dusky-hued races that hunt through the dark months of the year for

treasures that are coveted by cultured people.

Let a stranger enter the North; let him come to a far-out

fur Post, and he will be wonderstruck at the canine population; for if a

Post contain ten hunting Indians it is highly probable that the whole

foreground will be dominated by some 120 to 150 sled-dogs. The

proportion of man to dog is usually on such an astonishing scale.

It is certain that the stranger will wonder to see such

numbers of those uncommon beasts of burden, and possibly he will be

somewhat surprised that the natives of the Far North so extensively rear

dogs for utility, with much of the same purpose as his own people would

rear horses in the civilised South.

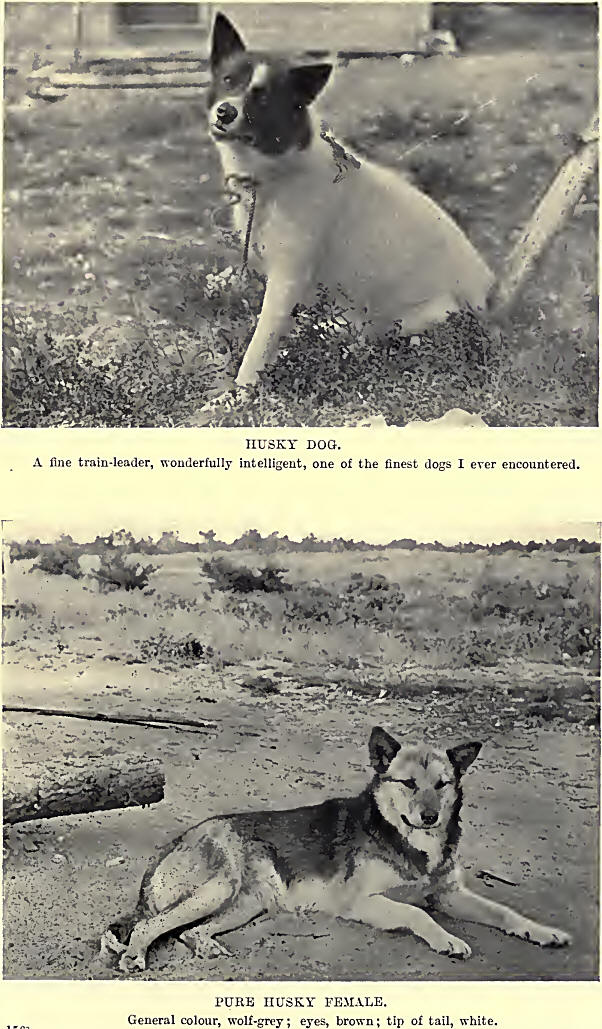

And he cannot but remark the striking presence, and

stalwart wolf-build of those dogs: some half-wild, disdainful, powerful;

beautifully proportioned, beautifully coated; others less handsome

cross-strains, rough-coated, unevenly coloured, but brim-full of courage

and strong to endure.

To find the true type of sled-dogs, or wolf-dogs, or

huskies, or malamoots—call them what you will out of those names of the

country— one must come to the far-out fur Posts ; for good dogs, like

good Indians, lie nowadays beyond the outposts of the white settler.

That the finest dogs are in the Far North is perhaps due to their

untrammelled surroundings, and to the nature of their feeding, for, on

the fringes of the Frontier, fish, the chief dog-food, is often scarce,

and in demand for human food, whereas in the Far North fish are

plentiful and little sought in the clear waters of the countless lakes

and rivers that abound in those distant places. Moreover in Frontier

settlements, and such Posts where white and halfbreed and Indian

intermingle, and are unsettled by more modern enterprises than the

old-world, patient, plodding fur trade, the sled-dogs are often outcast

when their winter’s work is done, and remain through summer no man’s

care, little better than thieving curs, kicked and abused by everyone.

If you are travelling north, particularly in summer, it

is sure to be your misfortune on the early outward trail to run foul of

those thieving fellows, who instil in you a firm distrust of every

sled-dog in existence long before you have cleared their unhealthy

habitat. All sled-dogs steal—even the best of them—but the untended

outcasts of the Posts near the edge of civilisation are particular

vagabonds. My most memorable losses by dog-thieves—memorable because

they seriously shortened my carefully calculated food-store on a long

outward canoe journey between two posts—was the loss of a shoulder of

dried moose meat, stolen from over my head at night, and a week’s baking

of “bannock” (sour-dough bread) plundered a few days later from a grub

box in camp during a heavy storm.

It is not uncommon to find an outcast dog, or a lost dog,

living along the shores of lake or river like a totally wild animal.

Living thus they gather oddments of food from the water’s edge, besides

what live prey they catch, such oddments as dead fish that are washed

ashore, or carcass of duck or gull; sometimes too they chance on a nest

of eggs, while if there are berries ripening in the woods they will even

devour those in their hunger. It is under such circumstances that one

may observe the full reawakened wild-natured cunning of those brutes,

for their sense of smell when roaming thus becomes keen and suspicious

as a wolf’s, and they will examine any particle of food with great care

before daring to touch it, as if they feared poison or a trap with all

the dread of a once caught, once escaped, wild thing. If you want

further proof of how close they are to their wild forefathers, watch

them at dusk, cunning as wolf or fox, and as naturally stealing through

the pine woods over dry, moss-grown knolls, eyes and ears and nose

alert, treading stealthily with head forward and tail straight, ready

instantly to pounce on spruce-grouse or rabbit or any living thing the

high-strung senses may detect.

There is one thing in the way of food that, as far as I

know, a sled-dog will not touch, and that is mice. I’ve seen dead mice

lying outside cabins for days untouched, where ravenous sled-dogs

existed. This is peculiar, because some domestic dogs will eat mice,

though it is true they are often sick after doing so.

I have said that all sled-dogs will steal. I’m afraid

that is true, and I cannot revoke even such sweeping judgment, but what

I like about the dogs in the Far North is that they have the grace to

acknowledge themselves rascals, for they stand aloof from mankind,

half-wild, half-afraid, making no overtures or pretences of friendship —

and they steal whenever they ean. On the other hand, poor-caste mongrels

of the Frontier may sidle up to you in friendly fashion, and you, in

good humour, may treat them kindly—then turn your back, and they sneak

into your tent and plunder whatever is at hand. This sort of thing can

be very annoying, and the only thing to do is to steel one’s feelings

against all and treat them as rogues—every one.

I will leave now the sled-dogs of the Frontier and deal

entirely with the more pure, more attractive types of those that are

common to the borders of the Arctic. Perhaps some of the finest dogs I

have seen were at Fort l)u Brochet, at the north end of Reindeer Lake,

where the Hudson Bay Company have stretched a tendril through inland

wilderness almost to the line of the Eskimo country, and there

established a Trading Post for Chipewyan Indians and those said Eskimos,

so that they be induced to bring out the fur of a large inland area of

the Barren-grounds and lay it on the rude barter counter of the Fur

Traders’ Store and purchase in exchange such luxuries as flour, and

tobacco, and tea, and ammunition, and beads, and coloured cloths, and

all such sort of things as are eagerly sought by simple, primitive

natives. Once a year a small band of Eskimos travel south with

fur-loaded sleds to Fort Du Brochet. Thereafter they are neither seen

nor heard of until another year comes round. They bring with them pelts

of White Wolves, Arctic Foxes, Bears, Wolverine, and a few Musk-ox

skins—the last-named animals believed to be rare nowadays, but perhaps

not so rare as it is written down to be for it inhabits, in most cases,

country almost totally unknown to white men, and unapproachable.

Sometimes the Eskimos bring a few Mink skins in their packs, but never

Marten, which are indigenous to forested country.

But to return to the subject of sled-dogs; there are

eight cabins at Fort Du Brochet, including the fur-traders’, and the

inhabitants of those owned twenty-two trains of sled-dogs: that is to

say, no adult dogs, while a conservative estimate of pups—three to six

months old— would add some forty head to the total dog population of the

Post. Remember that only records the number of dogs within that tiny

settlement, for beyond, on lone lake and river, at the isolated cabins

of the nomad Chipewyans of the territory, were the dog-trains of each

hunting Indian—perhaps three hundred to four hundred dogs in all in that

district, if one might guess a broadly approximate estimate.

And there are times, if one camps at Fort Du Brochet,

when one is very forcibly reminded that there is a mighty congregation

of dogs there, for, on certain nights, without visible cause, it is the

custom of the whole dog tribe to simultaneously point their muzzles to

the moon, and in one voluble, blood-curdling chorus to break in on the

unbounded silence of the northern night with their wolf-like, melancholy

dirge—long-drawn-out howlings, one......wow . . .wow. . . wow. . . oue............

Abruptly as the dogs commence, so is the wild call hushed, after giving

but a minute’s utterance to the wild sad spirit that has been handed

down to them by nameless forefathers from generation to generation.

Particularly on stormy nights do those strange animals show restlessness

and their desire to voice their wolf-howl to the whole world.

They howl also in this same deep, melancholy way when a

permanent camp is broken up and their masters embark in canoes for fresh

hunting-grounds. Then they will sit and howl their very souls out before

they bid good-bye to their old haunts and follow the canoes along shore.

It may be that they howl in dread of the unknown journey before them, or

with wish to send their dog-message of departure through shadowy forest

that holds the secrets of many wanderings and of many wild things. Be

that as it may, in due course they depart, and commence the hard task of

following the canoes, for to keep in touch they must at times swim from

point to point of deep bays, and cross wide rivers, and in a day fall

far behind in surmounting the difficulties in their path. At night they

may overtake their masters. But only the robust and hardy dogs get

through with the canoes, for the weaklings fall out and are lost, and

may only reach camp in a starved condition a week or two after the

others if they have been persistent and intelligent in following the

trail of their fellows.

It will have been gathered that all sled-dogs are idlers

in summer; many but little cared for, since the caring means work;

others are more fortunate who have masters who consider them their

property summer and winter.

Every summer day, except when storms of wind prevent

them, canoes go out to fishing-grounds from Fort Du Brochet to lift

their gill-nets and bring in fish for human food and dog-food. And every

day the keen eyes of many eager dogs watch from the shore-front for the

return of the canoes, which they welcome at the water’s edge, in a

body—much in the manner that hand-fed colts cluster to their

grain-trough at feeding hour. If the catch allows it, each dog gets one

fish per day in summer—Whitefish, Jackfish (Pike), or Trout, weighing 2½

lbs. upwards. Down by the water’s edge, when a canoe runs ashore, there

are gathered other dogs besides those belonging to the two fishermen at

the moment landing. Therefore, when they are ready to feed the dogs, one

Indian steps ashore armed with a stout stick or pole and stands among

them to preserve order, and guard against the interlopers, while the

other calls the name of a dog in deep tones as he tosses a fish from the

canoe into the air toward the dog he has selected, which dog adroitly

catches the fish in the air, rounds his shoulders protectingly over it,

and commences to tear it to pieces while holding it between sharp-clawed

fore-paws. Thus the fish are distributed to the rightful dogs. There is

seldom any mad rush ; both dogs and men know their business. The fish,

once dealt out, are devoured in ravenous, hasty gulps, while the strange

dogs pounce in now and again to try and steal from the rightful owners,

the while emitting fierce snarls and teeth-gnashings with thought to

overawe the one assailed. But the Indians watch with their poles, and

lay about them whenever a row arises; and growls and sounds of fierce

battle are immediately succeeded by the sharp yelp of a beaten dog—then

peace. Sometimes a dog carries his fish into shallow water away from the

others and tears it asunder with head under water; finally seeking below

the surface to be quite assured that no bits have been overlooked. In

barely a minute the repast is over, so powerful are the wolf-jaws of

those animals, so great their ravenous haste to devour their prey.

Everywhere in the North native laws of man and beast are

stern, even merciless; the outcome, perhaps, of living half the year

face to face with the powerful elements of winter, eternally fighting

for an existence within the zone of the greatest counterforces of life

to be met with in the whole wide world. Thus it appears, at first sight,

brutal to a stranger to witness the Indians punish their dogs on the

slightest provocation, and it is brutal in a delicate sense, but not so

in the mind of Indian or dog, for both are of a vigorous outdoor world,

and of primitive hardihood. Indians have full experience of sled-dogs.

They are masters of the situation; were their dogs allowed to run

unchecked* all summer, or be humoured by pampering kindness, they would

be useless as sled-dogs when the snows came. Hard blows teach them

always to respect the power of man, and to stand back at a respectful

distance and in due humility.

Regarding dog punishment, I have only once witnessed a

squaw severely deal with one of those provoking animals. Her men-folk

were away hunting, and her peculiar method was to tie the culprit to an

alder bush and belabour him mercilessly with a heavy pole until one

thought that if she did not cease speedily the dog would be beaten to

death. He had stolen something, poor hungry, wolf-natured brute—and he

would steal next hour, I wager, if the chance arose, licking or no—only

with a little more caution, a little added resolve that his cunning

would outwit his masters.

At freeze-up I have seen young dogs that have never

before been caught and harnessed prove so savage when handled that they

could not be put in the traces until stunned with a blow on the head.

For two or three days such dogs are unmanageable, but in the end they

become tractable and often prove splendid, hard-working, high-spirited

beasts of burden.

You will have gathered from these remarks that the

sled-dog is for ever in the foreground at the Far North fur

Posts—numerous beyond all other things—and that is true of them.

I will deal in detail with the foods on which sled-dogs

are fed, and then take you to the sled and the snowfield; that which is

their purpose of existence, and where their endurance and courage

overcome the bleakest wastes in all God’s Universe.

What food the natives subsist on is also the food of

their dogs. The year round the native and dog community of Fort Du

Brochet, and of many Far North Posts, live almost exclusively on fish

with the addition, in winter, of what deer-meat the Caribou migrations

provide. Raw fish, fresh from the water in summer, or frozen in winter,

is the chief dog-food the year round, and on this they thrive. And, in

this respect, it is certain that the fish on which the dogs of the

outermost Posts are fed has played an important part in retaining,

perhaps even developing, the fine physique which the breed obtain along

the trails of the Hinderland, for the fish from the pure cold waters. No

northern lakes are of surpassing excellence. The dogs themselves, when

occasion occurs, show discriminating taste, and marked preference for

their home fish, for, in the winter, should any dog-team go south to the

Posts of the Frontier it is noticeable that while being fed on fish from

inferior waters they will eat without relish and with an air of

distaste, and deteriorate in weight and strength.

Sled-dogs as a rule will eat any of the varieties of fish

that are caught in the North—Whitefish, Trout, Jackfish (Pike and

Pickerel), Black and Red Suckers, and Dory—but when not ravenously

hungry, and the opportunity offers, they will show a nicety of taste,

and their preference, by selecting the Whitefish, which is the choicest

to the human palate also.

In a country where food is the one great problem of

existence, providing for the sled-dog is no small matter, particularly

in winter. Therefore on the eve of the great freeze-up, with purpose to

store a large supply of fish for winter dog-feed, Fall fishing on an

extensive scale is yearly undertaken by the Indians. When the weather

turns cold in late September or early October, all the Indians of a

permanent camp depart to their well-known fishing-grounds—women,

children, dogs, teepee-covers, cooking-dishes are bundled into canoes by

their menfolk, and all set out for the various river outlets, where fish

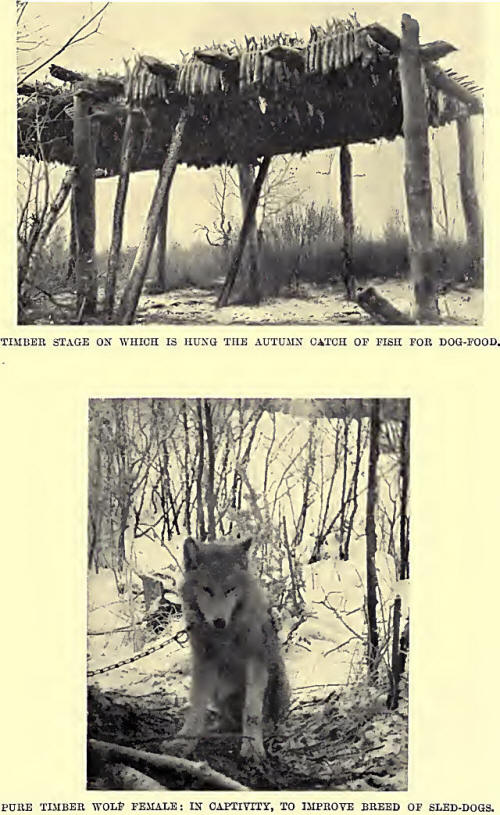

at that Reason congregate in their quest of spawning grounds. Each

Indian will set from three to four long gill-nets (usually 200 feet x 4

feet, with 2-inch mesh—manufactured, not native made), and those he

visits once a day in the cold grey autumn dawn before wind rises ; and

as a rule he brings in between one hundred and two hundred fish. When

landed the Indians and their squaws slit the fish through the body some

little distance from the tail, and truss them in tens on green

willow-rods of about two feet length. They are placed in groups of ten

so thatone stick conveniently allots a day’s rations to a five-dog

train—the usual number driven in northern territory. Large stages

constructed with the trunks of trees are erected, and across the

stalwart framework, from side to side, poles are spaced overhead to form

racks that receive the short rods of trussed fish, which then hang

suspended, head-downwards, well out of reach of dogs or wild animals.

Here the fish are frozen—sometimes completely, sometimes partially,

depending on weather; and keep, on the whole, almost completely fresh

until the hour the thermometer drops to zero and the great freeze-up

sets in.

When heavy snow has fallen, and sleds are out, the frozen

fish are transported from the stages at the fishing-ground, and stored

at the Indians’ cabins.

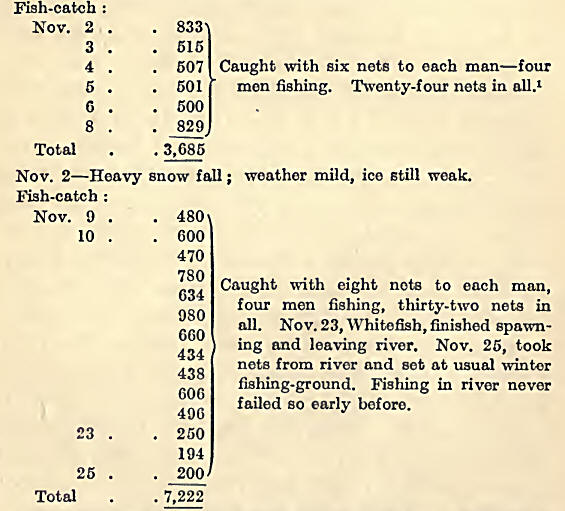

The total fish caught in this way varies. If a complete

freeze-up does not set in over-rapidly, one man may have 8,000, another

4,500, another 3.000—which is sometimes governed by the number of dogs

to feed, and sometimes by the ability and energy of the fisherman. Also

there is good luck and bad luck.

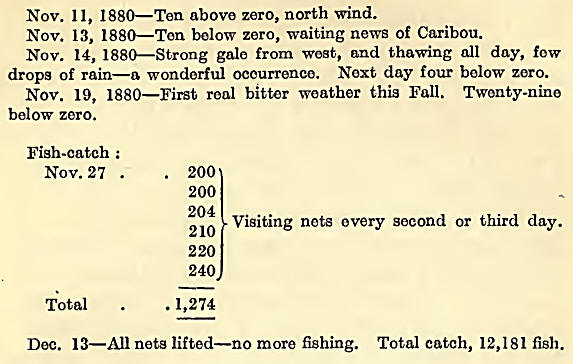

The following are some carefully kept, strange old

records of the autumn fish-catch at a Far North Post in 1880—almost

forty years ago!

Trailing over Ice and Snow

It was a starlit morning, about an hour from daybreak,

and cold as the very devil. I had got my five dogs into their harness in

the awkward, persevering fashion of a man with numbed, half frozen hands

working amongst frozen collars and traces in the biting cold, while

circulation is yet asleep. And now my team whimpered to be off on the

trail, while they shivered and looked miserably cowed with cold.

But there was a hitch this morning, one sled was not

ready to start. Mistewgoso was groping about the tree-bottoms and bushes

of the forest, trying to uncover a lost dog that was buried and hidden

in the snow and not inclined to turn out, being, no doubt, overtired

with the hard travelling of the past few days and comfortable where he

was. The Indian had circled closely around camp without success, then

set out upon a wider circle, and that unavailing he tried still another,

calling Natcheleaze—the dog’s name—ingreatimpatience,

and voicing the while his disapproval of the dog’s

conduct. Suddenly a yelp—Mistewgoso had unsnowed the culprit! Fully one

hundred yards from camp the Indian’s hawk-eyes had detected the dog,

though he had had to search so widely to find its snow-lair, and had not

overlooked it in the dark.

We were now ready to go. The dogs stood or lay, one

before the other, in their harness—harness made up of long, continuous

side-traces connected to saddle, and belly-band around their middles,

and to head-collars which rested on the fore shoulders and received each

dog’s pulling weight. But, having been left standing, of course some of

the dogs had got mixed up in their harness : they invariably do, as that

is accomplished by merely turning round or getting a leg or two over the

traces. Some mix-ups can be righted in a second; others take minutes and

the undoing of many buckles or thongs. However, traces were soon

straightened out this morning, while impatient dogs gave voice to their

wolf-howls in eagerness to start. Then each driver called out to the

leaders and we were off, while it was “Mush, Toyfayr! Mush, Corni! Tuok!

Tuok! Tuok! . . . Ge-kook! Ge-kook!” (to incite them to break into a

gallop and warm up). Then, “Ah! . . . Peesu!” in reproachful tones, as

you note the traces of that particular dog slacken, and how he is not

pulling his share. Again, when it is desired to change your direction,

the cry is “Hu, Corni (leader), Hu!” if the lead-dog is wanted to turn

to the right, or “Chac, Corni, Cliac!” if to the left.

There were three dog-trains on the trail, for two Indians

were with me—Mistewgoso and J’Pierre. We had been out a week, and were

still heading north.

North, always north, even against the stirring warnings

of the voices of the vast unknown, and the threatened overpowering grip

of the giant elements of heartless Arctic cold. At times it seemed

preposterous that against those forces such little things as we, mere

dust-specks in such mighty company, should dare to go on, and go on.

Ah ! there is power in the North, an almost overwhelming

strength of surroundings. You know you are up against it; within you you

are almost sure it will get you in the end, if you go just a little too

far, or are contemptuous for an hour of its antagonism.

On this occasion we were travelling far and travelling

fast. Those long, speedy-looking sleds, running lightly on the surface,

contained but a few “sticks” of fish for dog-feed, our rifles, axes,

snow-shoes, cook-cans, and deerskin sleeping-bags. 'We carried no

freight, though, if necessary, the sleds could be loaded up to 100 lbs.

per dog.

Light-fashioned those sleds looked; narrow, flat-boarded

things with curling, upturned prows, rear upright back-rest, rope

side-rails from back to front, and thereto attached the coffin-like body

of tough parchment skins which were laced up the sides and across the

bottom. But into such sleds an astonishing load can be packed. When

fully loaded the bundles of freight are piled to a height of two feet or

thereby, particular care being taken to have the whole well balanced

over the sled-boards; then all are laced into final position with

vice-tight ropings to prevent the load from slipping when the

sleds slew at turnings, or jar as the dogs lead overland, between lakes,

and the sleds dip into hollows, and over hillocks and fallen tree

trunks.

In weather we were fortunate, for there had been no deep

snowfall recently, and the powdery show had drifted and packed and the

surface on land or lake was everywhere firm. Snow-shoes had been

discarded. No trail required breaking. Overland between lakes (for it

was altogether a country of alternating lake and land) we sped,

light-footed in our duffel-lined moccasins behind ever-nimble dogs,

alert to keep the sled-head from being dashed against upright stumps or

dead logs that lay in our path

The hardest sled-driving is when passing overland:

guide-rope in hand, at one time urging the dogs uphill, at another time

righting the sled if a bad canting slope, or a hidden stump, has

overturned it. Then, perhaps, a mad scramble downhill, guiding the sled,

sometimes with somewhat random effort, as it sways from side to side in

its impetuous movement, buffered off the shallow banks which it

encounters on the margins of the trail. Finally, at sight of a lake

ahead, the dogs break into a gallop at prospect of getting on to the

level again, and the line of sleds debouch on to the lake from the

forest like a veritable cataract. Breathless, or if not breathless,

perspiring, we run alongside our sleds, board the protruding ledge at

the rear, and step over into the body to settle down for a rest while

still watching the dogs and urging them on. But before long we are out

on the ice again, trotting patiently behind the dogs, encouraging them,

and using the whip on any caught slacking (if not foot-sore, and

slacking with a cause), glad of exercise to keep up warmth against the

cutting cold wind we faced, and that swept over lake ice with the

freedom of wind on the sea.

Travelling light, and on packed snow, with no trail to

break, neither hunting en route nor trapping, it was estimated that the

dogs were travelling from four to five miles an hour. 'We were

travelling in three stages each day: that is, we halted to make two

“fires” between morning start and night camp. In each stage the dogs ran

between two and a half hours and three hours. Therefore the minimum

distance of travel per day- was thirty miles, and the maximum forty-five

miles.

When it was time to make “first fire,” a well timbered,

sheltered place was selected and the dogs run in to the lake edge.

Straightway a few spruce trees were felled on to the lake ice, their

branches lobbed off and spread mat-fashion on the snow to accomodate the

dogs, whereupon the teams, still harnessed to their sleds, were led on

to those “carpets” to there lie down, panting and tired, to cool off

while their feet and bodies were safeguarded from contact with ice and

snow. Back a little way in the shelter of the woods we then kindled a

camp-fire, filled the cans with water from a hole cut with an axe

through two feet of lake ice, and soon each one of us was enjoying

fragrant hot tea and pemmican, or lumps of cold Caribou meat saved from

the previous night’s cooking. Afterwards pipes and laughter while we

stood, first back, then front, basking in the luxurious warmth of the

log-fire.

The time of making “fires” of course varies. There is

really no mechanical measurement of Time in the Far North; only are the

spans of daylight measured by the sun, or by unfailing instinct if there

is no sun. However, a fair guide to halts on the winter trail are:

Morning Fire, 6.30 a.m. (about an hour and a half before daylight);

First Fire Halt, 9.30 a.m.—10 a.m.; Second Fire Halt, 2 p.m. — 2.30 p.m.

Night Camp, 5.30 p.m. (about an hour and a half after dark). It is on

account of those customary halts that Indians always answer questions as

to how long a journey will take by giving you the number of times they

sleep or make fire. Thus they say: “To go Eskimo camp, we sleep ten

times” (twelve days’ travel); or again, “To go Gull-foot’s wigwam, we

make two small fires” (about six hours’ travel); or “two long fires”

would mean about nine hours’ travel.

Throughout the day we kept trailing into the North over

river and lake and land that ever changed in line and aspect yet never

lost the dead white countenance of frigid snow. The “first fire” we left

behind, and the second, as we had done on the days before—each marking

so much gained on the scale of man’s ambition to explore, yet piling up

the leagues of snow that lay behind, lengthening the gulf between

solitude and the voices of fellow-mankind.

Even after the short winter’s day had ended we were still

calling to the dogs and urging them onward as they flagged at the end of

a hard day’s work. The wind had dropped, it was some degrees more

intensely cold, and, outside our small activities, the whole vast land

was deadly still with silentness. On, ever on, like a shaft of black

shadow, the line of sleds crept toward the head of the large lake we

were crossing, until our moving forms were brushed from the level white

surface and engulfed in the darkness of the dwarf forest on shore.

Among the trees we made camp. The sleds were drawn into

position to barricade our sleeping ground against the dogs and the cold;

and then the dogs were released from their harness. Boughs were cut and

laid for the dogs to rest on, and then all hands turned toward making

the night’s camp. Space was cleared sufficient to accommodate a large

log-fire and our outstretched forms. The fire was kindled at the edge of

the space down-wind; up-wind, the full length of our bodies from the

fire, the back of a two to three foot barricade was built, while similar

sides enclosed our camping space to the fire, which counted the fourth

side of our enclosure. This threesided barricade before the fire was

partly formed with sleds, and completed with felled trees and

snow-banking.

As soon as the fire was well ablaze the “sticks” of fish

were ranged before it to partially thaw out before being fed to the

dogs. While this was being done the camp was laid with a thick mattress

of boughs so that we would not sleep directly on the snow. Also a great

pile of dead timber was gathered for the night fire.

Those things were completed and the dogs fed (two fish

each) before any attention was given to our own wants. Thereafter pots

of meat were boiled over the blazing fire, and tea, and we ate with the

deep content of lean and hungry men.

In time the camp was ready to sleep. Beyond the fire

glare most of the dogs had ceased to move and had dug themselves holes

beneath the snow. Mistewgoso made a final round outside the barricade to

make sure the sleds were thoroughly protected from ravaging dogs—some of

whom would prowl stealthily round camp like wolves after we slept—then,

when he returned satisfied, clad as we were in our heavy fur clothes, we

curled into our fur-lined sleeping-bags—feet to fire, and sheltered by

the barricade from wind—and forgot the cold and the trail in dreamless

sleep.

I have endeavoured to describe a day on the north trail,

particularly the mode of travel. I have known many such days—their

food-shortage: no Caribou: dogs weakening, dogs footsore, dogs dying :

and Indian companions losing faith. Travelling north is not free of risk

at any time, it is far from pleasant then. But when without food in

bitter weather those dogs of endurance will gamely do their best for

three or four days and may save an anxious situation in the end. It is

then that one learns the greatness of their strength, and the spirit

that resists to the last blood-drop, unmurmuring, Big as the

stern-disciplined North that has mothered them. |