|

Day was breaking, and cold mist, less white than the

virgin snow, hung over the land; slowly it was lifting now that the long

winter night was over.

Gullfoot came to the door of his cabin, fumbled a moment

- to release the wooden peg-latch, coughed heavily, and looked out in

grave contemplation of the dreary scene while. chill air searched like

deadly serpent in through the open door. The clearing, the great expanse

of frozen lake to North and South, the dark forest background : all were

familiar and dear to his heart. But to-day he saw them not in

appreciation, for his thoughts were with the weather and its overnight

effect on his long trap-line.

A little fresh snow had fallen; enough to spoil Fox-traps

on the lakes if wind should arise and drift it: but, wind or not, other

traps, set in the shelter of the forest for Marten, and Mink, and

Wolverine were safe from being smothered, and the better disguised of

human scent, now that they lay beneath this light, fresh covering of

snow. . . . Hud! there was no need for anxiety this day : traps were not

buried in two or three feet of fresh snow; and there was no indication

of storm.

Gullfoot did not stand long at the door: a moment was

enough to idle there in zero weather when warmth was within; and enough

time, too, for him to read the weather and make deductions. But even in

those moments in the morning air that racking lung cough of his broke

out again and shook the very foundation of his frame as he closed the

door behind him. Alas! it was often so with him in those bleak winter

mornings, for this strong, athletic figure of a man, whom you might

think could not know sickness, was touched with the Indian plague and

had in him the seeds of consumption, though no hectic flush could ever

mantle his copper-bronzed face to betray in that its presence.

Gullfoot’s winter cabin was of logs, built with care with

the stunted scrub pine of the surrounding country. It was a small low

building of sturdy appearance; the four corners were notched together

with the accurate skill of a practised axeman; the walls were straight,

and grey as stone with the clay-mud which filled the cracks between the

timbers; the roof, which was thickly thatched with marsh-hay, pitched

steeply and threw deep shadows at the eaves—a simple, primitive

dwelling, but true to its purpose to withstand the rigour of Arctic

winter and afford full shelter for its inmates.

Indoors there was warmth and comfort, and pleasant scene

of native homeliness. The low room, to which Gullfoot returned from his

survey at the door, was dimly lit from a single small window opening in

the south wall, across which was stretched a sheet of clear skin

parchment to serve as “glass.” The walls were ornamented with beadwork,

some old bows and arrows, a powder-horn, and a muzzle-loading,

lead-ball, flint-lock rifle hung from wooden pegs in rare disorder. The

bed, which nestled close to one wall, was framed with boughs from the

forest and filled in across with light branches to form the “spring,”

while, over this, laced hay-grass furnished a mattress: the whole was

abundantly covered with thick warm Caribou rugs. A crude table and three

chairs occupied the centre of the floor, articles hewn smooth with axe

and knife, and much labour, from the woods of the forest, and grained

naturally with constant use. In the far corner a log-fire blazed

brightly in a hooded, stone-built fireplace, and threw its light in

dancing wavelets along the darkly smoke-fumed timber of the rude-cut

ceiling beams. A _ black iron pot hung over the fire, hooked to a rod; a

dwarf wooden stool was by the hearth. On the wall close to the fire,

pots and pans filled a shelf close to the floor. Overhead a string of

dry medicine roots and a fir e-bag hung from a rafter.

At the fire an Indian woman was preparing food, and, as

was her habit, she but glanced up as the man came in and continued her

duties without a word. Her face was set and grave as became her age, for

the countless withered wrinkles told that she was in the autumn of life

Hers was a shrunken face rather than full, and the skin was bronzed as

with a deep sunburn. In the profile lay character, for the outline was

straight and refined, and firmly chiselled with the impression of

endurance and patient strength. Enhanced by jet-black hair and deep dark

eyes there lurked still in this face the shadow of bygone comeliness and

of proud native womanhood. The figure, which was clothed in black

European clothing, excepting the tanned moccasined feet, was tall and

erect, unbent with the weight of years, and hers was a bearing that

bespoke activity unusual to one of her years, even among the tribes of

her own enduring people.

Her name was Nokum, the squaw of Gullfoot.

There were no children in the cabin. Two sons and a

daughter there had been, who had married and gone to hunting-grounds of

their own.

Gullfoot himself was a pure Chipewyan Indian: chief of

hunting people in manhood, child all his i life of the waste places near

to the edge of the Barren Grounds where the Eskimo is neighbour over the

marches to the north. He was a handsome man even at fifty; a very

handsome man. He had beautiful, even features throughout: a broad

forehead—typical of the Chipewyan race—high cheek-bones, a finely shaped

nose, a strong, square chin and a firm, clear-lipped mouth. In stature

he was tall for an Indian, being not much under six feet, perfectly set

up, active in every movement; lean; an athlete, every inch of him; and

at times this man’s bearing and reserve was that of a monarch, a man

whom you instinctively felt had pride of race, and on whom you could

never look as an inferior. But he was no monarch, and made no pretence

to be. The days of the Great Chiefs were over, though drops of their

blood remained. Gullfoot was Indian, and therefore a hunter and wanderer

by instinct, and to know him at heart you had to look in his eyes, eyes

that were dark almost to blackness yet alive with light and activity; to

know him still better you had to go with him out on the trail and marvel

at the skill and resource of this primitive man, while realising how far

his education and intelligence were ahead of your own in reading every

mood of the wilderness—the elements and the creature things—on which the

welfare of white man or red wholly depend if they are to exist in his

country.

About noon on the previous day I had landed at Gullfoot’s

cabin greeted by the fierce barking of his dozen sled-dogs, whose

clamour he came out to quell while welcoming me in. It was then bitterly

cold—zero weather, with a strong wind blowing from the north-west.

Sun-dogs, or parhelion, a bright mark of short perpendicular lines of

softly hazed, luminous rainbow tints of almost similar radiance to the

sun, had been showing in the morning sky on either side of the low

winter sun at wide but equal intervals from it; phenomenon peculiar to

the dead of winter. And it was indeed that season—the Dead of Winter:

Gullfoot, the following morning, quaintly showed me his record that it

was so, in pointing to the rising sun where it struck through the window

into the very corner in the north-east interior of his cabin. It was

thus in his home that he measured the shortest days, and the longest

days : in the height of summer, he told, “it reaches away to that

axe-notch in the centre of the north wall.”

Gullfoot made me welcome, and I was glad of the luxury of

shelter of a house-roof, and to obtain food for my far-spent dogs. Do

not ask me where I slept in this single-room cabin. I did not turn the

good people from their couch, and I was comfortable nevertheless, and

thought it considerable good fortune to be indoors.

In the meantime I had arranged that I would accompany

Gullfoot on his next round on his trap-line.

He would go to-morrow, he told me on his return from his

morning weather survey through the door, for he thought the wind would

rise later in the day, and if so his traps on the lakes in exposed

positions would require resetting. He had been out six days ago,

to-morrow would be the seventh day, and the weather in the interval had

been particularly good and promised some pelts.

So I had a day to wait at the cabin.

Gullfoot employed part of his time on the construction of

a new sled—a sled with runners on either side of about a foot depth

below the sled-board bottom; not the flat-bottom, runner-less sled of

the type common to the Indians a few degrees further south, where larger

wood for broad boards is obtainable. The runners he made were peculiar,

for they had no frame, no iron “keel”; just layer after layer of wet

moss laid on and frozen stiff until the runners were fully formed and

shaped, when they were then axe-pared, and planed to smoothness, and

iced over by applications of coatings of water. They

were, on completion, veritable planks of rigid ice, with stout adhesion,

and latitude for expansion and contraction secured by the admixture of

fibrous moss. A sled so made serves well; verily “necessity is the

mother of invention.”

While thus working, outside the cabin door Gullfoot’s

dogs, and my own, prowled about; but to those he paid no visible heed.

An Indian has no warm affection for animals, and Gullfoot was no

exception. However, in reply to my questions, he pointed out his best

team, and named them in Chipewyan—which names were in English

translation Day Star, Raven, Smoke, Evil Eye, Lynx!

Those dogs were typical of an Indian’s team in the north,

and therefore, perhaps, worth brief description: Raven: A very big

husky, larger than the common, and with longer, almost shaggy hair. He

was black in colour except for a fawn mark on the eyebrow over each eye.

Gullfoot used him in his team as the sled-dog—the dog next to the prow

of the sled—where his weight served well to steady the slew, or

buffeting, of the sled when in motion.

Smoke: A dog of striking colour, and purity of breed. A

splendid-looking husky in form; and white throughout with just a tinge

of buff. He was such a dog as everyone in a city would turn to look at

in admiration and wonder, did you transport him there. He was a good

worker and well broken.

Evil Eye: This unfortunate dog was blind in the right

eye, which shone glassy green. Otherwise he was without blemish and a

fine, powerful, active-looking dog. He was grey-wolf colour except for

an odd white left-shoulder mark.

Gullfoot reports him bad to harness, being restless and

excitable, and always twisting himself in the traces at a halt; but he

was a good dog otherwise.

Lynx: A little short-limbed active dog, about the size of

a highland collie, with a much-scarred nose and a reputation for

fighting. lie was a crossbred dog with drooping ears, and was chiefly

black in colour, with brown belly and paws. A dog one would not look at

twice, but worth his weight in gold. “My best dog,” said Gullfoot;

“pulls hard, has a great heart for work, and doesn’t know when to quit.”

He looked it: game through and through.

Day Star: Neither a husky nor a cross-bred sled-dog; just

a mustard-yellow terrier-hound mongrel with scant, close-set coat of

hair to withstand cold. She had a white star-mark on her forehead, but

she was well named on a second score, for she it was who guided the team

at Gullfoot’s bidding. This was Gullfoot’s leader; an animal of

wonderful intelligence, he told me, in following snow-covered trails,

and with a memory almost more acute than that of a human being for

places she has once passed. Gullfoot showed his appreciation of her in

covering her short-haired body with a blanket-rug to help keep her warm

when on the trail; a considerable, and rare, condescension on the part

of an Indian toward a dog.

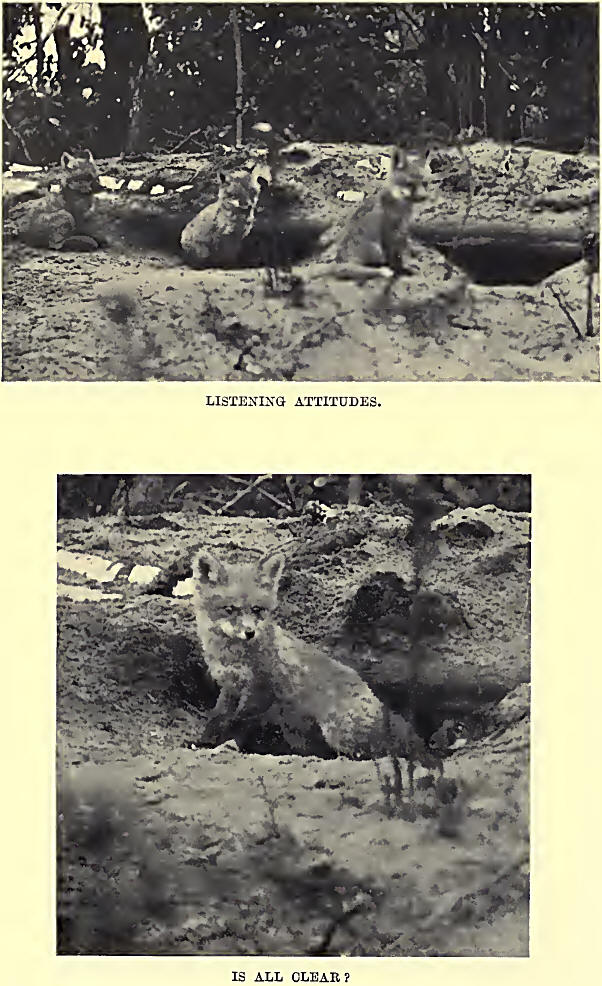

After discussing dogs, we talked foxes. Everyone in the

North talked foxes in 1914. With the floating of Fox Farms in the

Eastern Provinces the demand had gone up for live fox cubs of all kinds,

and hunters were tremendously stimulated by the enormous prices given

for silver or black cubs, which to the fortunate captors represented a

veritable gold-mine.

In April and May, when the fox-dens are located and the

cubs dug out, places such as Big River and lie a la Crosse were

“fox-crazy,” and the whole territory within reach was being scoured for

Reynard.

This wholesale capture of foxes serves the mood of the

moment, but I fear there are yet to be many regrets when both trapper

and fox-merchant come to realise that they have killed “the goose that

laid the golden egg.”

If wild-fox fur is to remain a valuable asset to Canada,

digging out the young in the early spring should be made illegal by law,

or limited by law to a very stringent degree. The export of live

foxes is governed in a degree by the issue of permits, but these permits

in 1914 were generously given, it seemed to me, and, moreover were often

evaded; nor was it possible in out-of-the-way places to follow the

movements of keen buyers or the extent of their purchases.

Again, in 1914, by a recent revision of the Game Act, it

was unlawful to take foxes before May 15. This restriction was seldom

observed north of the frontier, cubs were dug lust when the dens

contained them, and kept until they were wanted by the buyer. Such a

state of affairs would cease if it was unlawful to dig out foxes and

unlawful to buy foxes, except, perhaps, in a very limited degree, and

only under Government supervision. Obviously, if it is desired to

preserve a declining species of any kind, mankind must protect it at the

time it is bringing forth young. And it should be borne in mind also

that many of the foxes are dug out of their dens when but a few days

old, and a large percentage totally lost during early captivity, when

artificially mothered and artificially fed.

Moreover, it may be doubtful if Fox Farms, the booming of

which has been a means of entertaining public speculation, will have any

great success beyond a temporary one. Foxes roam far, and are very

restless in their wild state, and it seems idle to expect other than an

inferior race from production in confinement, even though the farms

succeed in increasing the number of Black and Silver Foxes, which is

their object. Temperament, freedom, food and temperature— for the

further north the better the fur—all seem to point to this. Thus

trapping the adult fox in its wild and natural haunts, in the few months

when the fur is at its prime, is conceivably the fairest way, and the

best, to encourage lasting fur trade, while, at the same time, such

trapping does not reduce the stock unduly. Furthermore, trapping the fox

in its native haunts worthily helps the Indians to a means of obtaining

what little luxuries they have; and those of them that remain of the

race of peoples whose country we have overwhelmed deserve every

consideration that can be given. It would be surely a pity to take away

from them a part of the trade which they have always had since their

first meetings with the white man.

The fur of those foxes under discussion is that which

eventually finds its way in great bales to London and Paris and New

York, to be eventually made up and marketed in costly robes. And it may

be of interest to here set forth some description of their definitions

in the country of their birth.

There is, as there is a wide range of colour, a wide

range of values in fox fur in the raw state in trapping country. A prime

black fox pelt may fetch, in accordance to size, £100 to £55, and the

all-silver fox £30 to £16. Between those prices are graded the

three-quarter-black (three-quarter-neck is the term of the traders),

half-black and quarter-black, whose definition of colour I will describe

further on. But those are the rare skins; the typical red, and ordinary

Cross fox, are worth about £l 65., the good Cross about £2 8s.

Pelts are bartered by the Indians for tea, sugar,

tobacco, ammunition, clothes, etc., etc., though sometimes a small

percentage of the transaction is in cash. All goods that pass in barter

are highly priced, for the heavy cost of man-transport over the long

difficult trail to the post has to be added, as also have losses en

route, and various percentage margins. So that stores that might be

bought for £30 at Prince Albert might be valued at say £50 at Fort Du

Brochet at the end of a summer’s transportation.

Dealing now with the range of colours: if one said that

one Black or Silver Fox was caught in every fifty foxes trapped, one

would be somewhere near the proportion of their rarity. I have arrived

at such a proportion from actual figures of catches in 1913. Estimates

many years ago, from one Hudson Bay district, of foxes caught over

twelve years—from 1848 to I860—stated that were silver or black, and of

the remainder cross, and red.1 Since then the black and silver foxes

have become more rare.

All foxes in the north of Canada, excepting the Arctic or

White Fox, are of the same species, though separated in trade, on

account of the varieties of colour, into four classes: Black, Silver,

Cross, and lied. There are grades of shade between the pure Black Fox

and the pure Red, but the above are well-defined limits to work on. Only

in two places is the colour unchanging, for the tip of the brush and a

small mark on the forebreast remain always white.

Regarding the actual production of the different

varieties: the offspring of two Silver Foxes might be silver; on the

other hand, such mating might throw back to Cross or Red ancestors. But

in any event foxes, in their wild state, do not cohabit strictly in

pairs. At the season of propagation a number of males accompany a female

much in the manner of dogs, and fight violently for possession of her;

and as those males may vary in colour, so may they give rise to the

varieties which may be found in a single litter.

The perfect Black Fox is glossy jet-black throughout,

excepting the small white mark on the forebreast and tail-tip, while

there may be a very few silver hairs on the back over the rump.

The Silver Fox is similar to the Black Fox, but may have

a greater or lesser area interspersed with silver hairs, and those areas

are usually designated in the Fur Posts by the

terms, "three-quarter-neck,” "half-neck,” and “quarter-neck.” A

three-quarter-neck Silver Fox is all black except over the rump and

hindquarters, which area is lightly interspersed with silver-grey hairs;

a halfneck Silver Fox is the same, except that the silver hairs extend

to the middle-hack; while a quarter-neck has the whole black body

interspersed with silver hairs excepting the head and neck, which are

all black.

The handsome Cross Fox has many variations of colour,

brought about by a greater or lesser amount of greys and a corresponding

variance of the extent of red. However, a typical Cross Fox has the

entire back and hindquarters thick-speckled stone-grey, and the forehead

and sides of head the same colour; the rear of the hindquarters and the

root of the tail, underneath, show pale whitish buff; the tail is black

on the upper side, excepting the white tip, and paler buffish black

below; the under-jaw, throat, breast, belly, and all limbs are black;

the sides behind the foreshoulders, and the neck behind the ears, are

reddish buff; the back of the neck is reddish-tinged grey with more

black showing than on the back; the back of the ears is velvet black;

the nose to the eyes is black with a few silver hairs.

Lastly, a typical Red Fox has a general body colour of

medium yellowish-red buff, with the belly and legs and the back of the

ears black. But it must be borne in mind that the Red Fox has degrees of

variation from this colour leading out toward the most reddish-grey

varieties of the Cross Fox.

By night Gullfoot and I had exhausted our fox-talk, which

had been sustained by my interest in his collection of freshly trapped

pelts, which he took some trouble to show me.

As full night came on, accompanied by inevitable increase

in low temperature, and Arctic array of Northern Lights, we turned in to

sleep 'with thoughts of an early start on the morrow.

Two hours before daybreak next morning we were astir in

the cabin, and, aided by a glimmering, fitful light from a vessel

containing liquid grease rendered from wolf fat, which fed a piece of

twisted rag to which light had been applied, we robed in our outdoor

clothing of Eskimo Caribou suits, and prepared and partook of food.

An hour before daylight, out in the bitter cold, our dogs

were harnessed and ready to start.

All day we travelled on Gullfoot’s trap-line through

forest and over lakes and rivers. By night we must have covered some

thirty to forty miles, and had visited forty traps, from which had been

taken one Cross Fox, one Red Fox, one Wolf, four Marten, and three Mink:

which Gullfoot assured me was a successful and gratifying result.

From this it may be gathered that trapping is not a

simple task, and animals not to be picked up in any abundance even on a

wide range. Broadly speaking, Gullfoot had one trap set to every mile,

and those sets resulted in one animal captured to every four miles. If

one assumes that Gullfoot trapped with equal vigour during the best

three months for fur, viz. November, December, and January, and visited

his trap-line every week with equal success, his total catch (thirteen

weeks x ten animals) taken in a season would represent practically three

animals to every mile of territory. One hundred and thirty animals, the

total thus arrived at, is, however, a much larger catch than is common,

and would in all probability, on an average, be much reduced by spells

of bad trapping weather lasting over a week or two, and consequent less

productive days than the one I write of, which was in any case,

apparently, a particularly successful one. Then, too, traps are

sometimes changed to fresh localities, often as far afield as three days

from the trapper’s cabin, which vastly increases the area covered; so

that, all things considered, it may even be doubtful if one mile can

produce to the trapper one fur-bearing animal in a season in the Far

North country immediately south of the Barren Grounds.

All fur-bearing animals, whose kind have been hunted and

trapped for generations, are exceedingly wary, and it is a revelation to

a novice to watch an Indian gravely make his sets with superb cunning,

sufficient, in some instances, to outwit the most wily of quarry.

I will endeavour to describe how Gullfoot’s traps were

set, which are the usual Indian methods.

His fox-traps, without exception, were always set in the

open snow on the ice near some prominent shore point of an expansive

lake, or near an island; or in the narrows which sometimes connect two

or more lakes. He had twelve traps set in such locations, strong

double-spring traps of the size known as No. 2. Those traps were chained

to a pole about six feet long and of calculated weight to prevent an

animal from travelling far, while at the same time it would give if

severe strain was put upon it; this latter to prevent the fox from

obtaining sufficient direct purchase on the trap in endeavour to break

its foot clear when caught. When a favourable spot had been chosen, the

log was carefully buried beneath the surface of the snow, and the trap

set, with a fine sheet of tissue paper—carried for the purpose, and

obtained at the Fur Post— laid over the pan and jaws to prevent snow

filling below, where it would choke the drop, and the whole then covered

with a light powdering of snow until every sign of human disturbance was

erased. A few morsels of meat or frozen fish were then spread near, but

not necessarily directly at, the trap, for it often allays suspicion of

a trap’s actual presence to allow the animal to find food in safety

during its first timid approach, when it naturally then becomes more

bold. The situation of the trap was usually near the top of a small

mound of snow, natural, or made up with snow, and somewhat resembling a

buried stone, for it is known that foxes are prone to investigate such

objects, probably in the hope that it is a snowed-over carcass of some

kind, or retains the scent of a comrade who has passed before.

Twice Gullfoot’s fox-traps were set in the neighbourhood

of a Caribou carcass, and one of the foxes taken was there caught. In

those cases the traps were not set at the carcass, but some distance

away, where the foxes would circle suspiciously before daring to

approach the quarry.

Traps for Marten were set in the forest at the foot of

dark spruce and pine trees. Gullfoot’s method was to make there a tiny

enclosure which in plan was like a U lying on its side, the bottom of

the U being the tree trunk, and two little palisades forming the sides

made with closely set upright stakes stuck into the snow. As in the top

of a U, there then remained an opening: and there the trap—a

single-spring No. 0—was set just within the entrance, while beyond the

trap, inside, next the tree trunk, was placed a fish head pegged down

with a stick: to reach this bait any animal desiring it must pass over

the trap. Over the top of the palisade; to shelter the trap from snow,

and the bait from the eyes of the thieving Canada Jay, a number of

spruce boughs were laid, and covered with snow to resemble the

surroundings. Footprints were then carefully obliterated for some

distance as we retraced our steps, and the set was then complete.

Mink-traps were often set in much the same manner, but in

very different surroundings; the chosen situations being about the

overhanging banks of narrows between lakes, or of frozen streams, for

those animals frequent the neighbourhood of water. In some cases

Mink-traps were set in naturally formed narrow runways at the bottom of

a bank, along which a small animal was almost sure to pass if it came

that way. Such sets were unbaited.

At one point in the forest Gullfoot had a cache of

Caribou meat, and below this he had set two powerful traps on the chance

of the store attracting a Wolverine. The cache was constructed with

three triangularly placed upright poles of length a little more than

man-height; the tops of those uprights carried horizontal poles, which

formed a V, and across this was laid a platform of .branches, upon which

the frozen meat was stored. The three upright poles were dressed free of

bark, and thus smoothed to prevent Wolverine from securing claw-hold, if

any should endeavour to climb to the platform overhead ; and there, on

the snow below the cache, the traps were placed, so as to ensnare any

such thief at his foul work—two traps required to hold this gluttonous

animal, which has a tremendous reputation among the Indians for strength

and capacity to break free after being caught.

By late afternoon we had reached the far end of

Gullfoot’s trap-line, and there encamped for a few hours to rest the

dogs before resuming on our way back to the cabin on a wide detour so as

not to further disturb the neighbourhood.

About 6 p.m. we started back through the bleak silent

land of snow, lit on the way by the whiteness underfoot and a clear sky

overhead, sparkling, in the crystal-clear atmosphere, with more stars

than one will see anywhere else in the world, unless it be at the North

Pole. Gullfoot and his dogs leading, with unerring intuition finding

their way through this land of awful greatness and sameness without

apparent trouble, as I might at home travel a road familiar to me.

At midnight we reached his cabin.

There was Nokum sitting by the fire, and the pot, filled

with Caribou meat, simmering slowly, awaiting our return.

Frozen sticks of fish were brought in from outside, and

set before the blaze to thaw out for food for the tired dogs, the teams

were unharnessed, and fed and their snarling ceased while we gathered

indoors to our well-earned repast and repose. |