|

SUCH was the

environment in which Robert Baldwin and his future colleagues in the

Reform ministry of Canada, entered upon political life. The Baldwins

were sprung from au Irish family resident on a little property called

Summer Hill, near Carragoline, in the county of Cork. The father of

Robert Baldwin had come out to Canada with his father (himself a Robert

Baldwin; in 1798. The family settled on a tract of land on the north

shore of Lake Ontario, in the present county of Durham, where Robert

Baldwin (senior) set himself manfully to work to clear and cultivate a

farm to which he gave the name of Annarva.1 His eldest son, "William

Warren Baldwin, did not, however, remain upon the homestead. He had

already received at the University of Edinburgh a degree m medicine and.

anxious to turn his professional training to account, he went to the

little village of York. Here he took up his abode with a Mr. Wilcocks of

Duke Street, an Irish friend of his family, who had indeed been

instrumental in inducing the Baldwins to come to Canada. In a pioneer

colony like the Upper Canada of that day, the health of the community is

notoriously sound, and Dr. Baldwin soon saw that the profession of

inedii ine at York could offer but a precarious livelihood. He

determined, therefore, to supplement it with school-teaching and

inserted in the Gazette an announcement of his intention to open a

classical school;— "Dr. Baldwin, understanding that some gentlemen of

this town have expressed an anxiety for the establishment of a classical

school, begs leave to inform them and the public that he intends on

Monday, the first of January next [1803], to open a school in which he

will instruct twelve boys in writing, reading, classics and arithmetic.

The terms are, for each boy, eight guineas per annum, to be paid

quarterly or half yearly; one guinea entrauce and one cord of wood to be

supplied by each of the boys on opening the school." It is interesting

to note that among the earliest of Dr. Baldwin's pupils was John

Robinson, distinguished later as a leading spirit in the Family Compact

and chief-justice of the province.

School-teaching with

the ambitious Irishman was, however, only a means to an end. The legal

profession, then in its infancy in the colony, offered a more lucrative

and a more honourable field, and for lbs in his leisure hours Baldwin

hastened to prepare himself. Indeed no very arduous preparation or

profound knowledge was needed in those days for admission to the legal

fraternity of "Muddy York." A summary examination, conducted in person

by the chief-justice of the province, was all that was required of

Baldwin as a candidate for the bar, and on April 6th, 1803, he was

admitted as a duly qualified practitioner. Ilis entry upon his new

profession was signalized by his marriage in the same year with Miss

Phoebe Wilcocks, a daughter of the family friend with whom he had lived.

The newly married couple took up their quarters in a new house on the

corner of Frederick and Palace Streets, the latter a street running

parallel with the shore of the bay and receiving its grandiloquent name

from the expectation that it would presently become the site of a

gubernatorial "palace." In this house Robert Baldwin, eldest son of

William Warren Baldwin was born on May 12th, 1804.

Little need be said of

Robert Baldwin's youth and school days. By no means a precocious child,

he was distinguished at school rather for a painstaking diligence than

for exceptional natural aptitude. lie received his education at the Home

District Grammar School, at the head of which was Dr. John Strachan,

then rector of York and subsequently distinguished as Bishop of Toronto

and champion of the Anglican interest. Baldwin's conscientious industry

presently made him "head boy" of the Grammar School, from whose walls he

passed with credit to enter upon the study of the law (1819). After

spend-ng some years in his father's office, he was called to the bar in

Trinity Term, 1825, and became a partner in his father's business under

the firm name of "W. W. Baldwin and Son." The fortunes of the elder

Baldwin had in the meantime rapidly unproved. Not only had he met with

success in his dual profession, but he had the good fortune to fall heir

to the property of a Miss Elizabeth Russell, a distant connection of the

Baldwins, and sister to a certain Peter Russell, a bygone magnate of the

little colony whose extensive estates she had herself nherited and now

bequeathed to William Baldwin. Desirous to use his new found wealth for

the foundation of a family estate,1 Dr. Baldwin purchased a considerable

tract of land to the north of the little town on the summit of the hill

overlooking the present city of Toronto. To this property the name "Spadina"

was given, and the wide road opened by Dr. Baldwin southward through a

part of the Russell estate was christened Spadina Avenue.

Both father and son

were keenly interested in the political affairs of the; province. The

elder Baldwin was a I .liberal and prominent among the Reformers who,

even before the advent of William Lyon Mackenzie, denounced the

oligarchical control of the Family Compact. But he was at the same time

profoundly attached to the British connection and averse by temperament

to measures of violence. While making common cause with the Mackenzie

faction in the furtherance of better government, Dr. Baldwin and his

associates were nevertheless separated from the extreme wing of the

Reformers by all the deference that lies between the Whig and the

Radical. The polit ieal aims were limited to converting the constitution

of the colony into a real, and not merely a nominal, transcript of the

British constitution. To effect this, it seemed only necessary to render

the executive officers of the government responsible to the popular

House of the legislature in the same way as the British cabinet stands

responsible to the House of Commons. This one reform accomplished, the

other grievances of the colonists would find a natural and immediate

redress. Robert Baldwin sympathized entirely with the political views of

his father. Moderate by nature, he had no sympathy with the desire of

the Radical section of the party to abolish the legislative council, or

to assimilate the institutions of the. country to those of the United

States. The Alpha and Omega of his programme of political reform lay n

the demand for the introduction of responsible government. His

opponents, even some of his fellow Reformers, taunted him with being a

"man of one idea." Viewed n the clearer light of retrospect it is no

reproach to his political insight that his "one idea" proved to be that

which ultimately saved the situation and which has since become the

corner stone of the British colonial system.

The year 1829 may be

said to mark the commencement of Robert Baldwin's public life. He had

already taken part in election committees and was known as one of the

rising young men among the moderate Reformers. He had. moreover, in the

election of 1828, unsuccessfully offered himself as a candidate for the

county of York. But in 1829 we find him figuring as the draftsman of the

petition addressed to George IV in connection with the Willis affair.

Willis, an English barrister of some prominence, had been appointed in

1827 to be one of the judges of the court of king's bench in Upper

Canada. While holding that office he had held aloof from the faction of

the Family Compact and had thereby incurred the displeasure of the

authorities, who had become accustomed to view the judges as among their

necessary adherents. A technical pretext being found,1 Sir Peregrine

Maitland dismissed Willis from office. The cause of the latter was at

once espoused by the Reform party. A public meeting of protest was

called at York under the chairmanship of Dr. Baldwin, and a petition

drawn up addressed "to the king's most excellent Majesty, and to the

several other branches of the imperial and provincial legislatures." The

pet: ' ion is said to have been drafted, at least in part, by Robert

Baldwin. The occasion was considered a proper one, not only for

protesting against the injustice done to Judge Willis, but for drawing

the attention of the Crown to the numerous evils from which the colony

was suffering. The list of grievances, arranged under eleven heads,

included the already familiar protests against the obstructive action of

the legislative council, the precarious tenure of the judicial offices,

and the financial extravagance and favouritism of the executive

government. Of especial importance is the eighth item of the list, which

called attention to "the want of carrying into effect that rational and

constitutional control over public functionaries, especially the

advisers of your Majesty's representative, which our fellow-subjects in

England enjoy m that, happy country." Following the catalogue of

grievances is a list of "humble suggestions" of adequate measures of

reform. The essential contrast between the moderate Reformers of Upper

Canada on the one hand, and the Radical wing of their party and the

Papineau faction of the Lower Province on the other, is seen in the fact

that no request is made for an elective legislative council. It is

merely asked that only a "small proportion" of the council shall be

allowed to hold other offices under the government, and that neither the

legislative councillors nor the judges shall be permitted to hold places

in the executive council. The sum and substance of the wishes of the

petitioners appears in the sixth of their recommendations, in which they

pray "that a legislative Act be made in the provincial parliament to

facilitate the mode in which the present constitutional responsibility

">f the advisers of the local government may be carried practically into

effect; not only by the removal of these advisers from office when they

lose the confidence of the people, but also by impeachment for the

heavier offenses chargeable against them." The petition was forwarded

for presentation to Viscount Goderich and the Hon. E. G. Stanley, from

each of whom Dr. Baldwin duly received replies. A quotation from the

letter sent by Stanley, who became shortly afterwards colonial

secretary, may serve to show to how great an extent the British

statesmen of the period failed to grasp the position of affairs in Upper

Canada. "On the last and one of the most important topics," wrote

Stanley, "namely, the appointment of a local ministry subject to removal

or impeachment when they lose the confidence of the people, I conceive

there would be great difficulty in arranging such a plan, for in point

of fact the remedy is not one of enactment, but of practice—and a

constitutional mode is open to the people, of addressing for a removal

of advisers of the Crown and refusing supplies, if necessary to enforce

their wishes." From what has been said above it is clear that this was

the very mode of redress which was not open to the people of the

province.

In this same year

(1820) Robert Baldwin first entered the legislature of the province.

John Beverley Robinson, the member for York and attorney-general, had

been promoted to the office of chief-justice of the court of king's

bench, his seat in the assembly being thereby vacated. Baldwin contested

the seat and was successful in his canvass, being strongly aided by the

influence of William Lyon Mackenzie. A petition against his election, on

the ground of an irregularity in the writ, caused him to be temporarily

unseated, but in the second election Baldwin was again successful and

entered the legislature on January 8th. 1830. In the ensuing session he

appears to have played no very conspicuous part, his membership being

brought to a premature termination by the death of George IV. The demise

of the Crown necessitating a dissolution of the House. Baldwin again

presented himself to the electors of York. In this election the

adherents of the Family Compact contrived to carry the day, and Baldwin

was among the number of Reformers who lost their seats in consequence.

During the year that ensued he had no active share in the government of

the country but continued to be prominent among the ranks of the

moderate Reformers of York with whom his influence was constantly on the

increase. To his professional career also he devoted an assiduous

attention. He had, in 1827, married Augusta Elizabeth Sullivan, whose

mother was a sister of Dr. William Baldwin. He now (1829) entered into

partnership with his wife's brother, Robert Baldwin Sullivan, who had

been his fellow-student n his father's law office, a young man whose

showy Intellectual brilliance and lack of conviction contrasted with the

conscientious application of his painstaking cousin. Of Baldwin's public

life there is, however, during this period, nothing to record until the

advent of Sir Praticis Bond Head brought him for the first time into

public office.

Among the intimate

associates of the Baldwins in the year preceding the rebellion, there

was no one who sympathized more entirely with their political views than

Francis Hincks. Hincks came to Canada in the year 1830. He was born at

Cork on December 14th, 1807. and descended from an old Cheshire family

which for two generations had been resident in Ireland, in which country

he spent his youth. He received at the Royal Bedfast Institution a sound

classical training. He had early conceived a wish to embark in

commercial life, which his father, the Rev. T. D. Hincks, a minister of

the Irish Presbyterian Church, did not see fit to combat. He entered as

an articled clerk in the business house of John Martin & Co., Belfast,

where he spent five years.1 On the termination of his period of

apprenticeship Hincks resolved to see something of the world and sailed

for the West Indies (1830), visiting Barbadoes, Denieraraand Trinidad.

At Barbadoes, he accidentally fell in with a Mr. George Ross of Quebec,

by whom he was persuaded to sail for Canada. After spending some time in

Montreal he determined to visit Upper Canada and set out for the town of

York, travelling after the arduous fashion of those days "by stage and

schooner," a journey which occupied ten days. Hincks spent the winter of

1830-1 at York, conceived a most favourable idea of the commercial

possibilities of the little capital, and interested himself at once in

the threatening political crisis. He was a frequent visitor at the

Parliament House, a brick structure at the foot of Berkeley Street,

intended presently "to be adorned with a portico and an entablature,"1

whose gallery was open to the public. Here, and in the hall of the

legislative council, which, in the words of an enthusiastic writer,

"corresponded to the House of Lords" (being "richly carpeted, while the

floor of the House is bare,") Hincks listened to the exciting debates of

the session in which Mackenzie was denounced as a "reptile" and a

"spaniel dog," and expelled by the indignant majority of the Tory

faction. Early in 1831 he left Canada for Belfast to "fulfil a

matrimonial engagement" which he had already a Buckingham, contracted.

The matrimonial engagement being duly fulfilled (July, 1832), Hincks

returned to Canada to settle in York. Here he became one of the

promoters and a director of the Farmers' Joint Stock Banking Company;

from this institution Hincks very shortly seceded, on account of its

connection with the Family Compact. In company with two or three other

seceding directors he joined the Bank of the People, which was

established n the interests of the Reform party. Of this bank Hincks was

manager during the troubled period of the rebellion. With Robert Baldwin

and his father the young banker had already formed an intimate

connection. Hincks's house at No. 21 Yonge Street was next door to the

house occupied at this time by the Baldwins, to whom both houses

belonged.1 The acquaintance thus formed between the families ripened

into a close friendship from the time of his arrival at York. Hincks's

practical good sense had led him to sympathize wTith the moderate party

of Reform, and he now found in Robert Baldwin an associate whose

political views harmonized entirely with his own. In addition to his

management of the Bank of the People, Hincks was active in other

commercial enterprises. He became the secretary of the Mutual Assurance

Company, founded at Toronto shortly after his coming, and appears also

to have carried on a general warehouse business at his premises on Yonge

Street. That his eminent financial abilities met with ready recognition,

is seen from the fact that he was appointed, in 18.13, one of the

examiners to inspect the accounts of the Welland Canal, at that time the

subject of a parliamentary investigation. The practical experience and

insight into the commercial life of the colony which Hincks thus early

acquired, enabled him presently to bring to the financial affairs of

Canada the trained capacity of an expert.

At the time when

Baldwin, Hincks, and their friends among the constitutional Reformers of

Upper Canada were viewing with alarm the increasing bitterness which

separated the rival parties, a new lieutenant-governor arrived in the

province whose coming was destined to bring matters rapidly to a crisis.

Francis Bond Head was one of those men whose misfortune it was to have

greatness thrust upon them unsought. He was awakened one night at his

country home in Kent by a king's messenger, who brought a letter from

the colonial-secretary offering to him the lieutenant-governorship of

Upper Canada. Head was a military man. a retired half-pay major who

received his sudden elevation to the governorship with what he himself

has described as "utter astonishment." On the field of Waterloo and

during his experience as an engineer in the Argentine Republic, he had

given proof that he was not wanting in personal courage. Of civil

government, beyond the fact that he had been an assistant poor law

commissioner, he had no experience. Of politics in general he knew

practically nothing; of Canada even less. Nor had he a range of

intellect such as to enable him to rise to the difficulties of his

position. With a natural incapacity he combined a natural conceit, to be

presently enhanced still further by his elevation to a haronetcy.

Convinced of his own ability from the very oddness of his appointment,

he betook himself to Canada puffed up with the pride of a professional

pacificator. How Lord Glenelg, the colonial secretary, could have been

induced to make such an appointment, remains one of the mysteries of

Canadian history. Rumour indeed has not scrupled to say that the whole

affair was an error, that the name of Francis Head had been confused

with that of Sir Edmund Head, also a poor law commissioner and a young

man of rising promise and attainments. Hincks in his Reminiscences

asserts that he was informed of this fact in later years by Mr. Roebuck

and that a "distinguished imperial statesman had also spoken of it."

In so far as he had had

any political affiliations in England, Head had been a Whig. The news of

this simple fact had gone before him, and the Reform party were prepared

to find in him a champion of their interests; Sir Francis in consequence

found the role of saviour of the country already prepared for his

acceptance "It was with no little surprise," he writes in his Narrative,

in speaking of his first entry into Toronto (January, 1830), "I observed

the walls placarded with large letters which designated me as Sir

Francis Head, a tried Reformer." The administration on which the new

governor now entered was from first to last a series of blunders. It had

been impressed upon him by the British cabinet that he must seek to

conciliate the Reform party and to compose the factious differences by

which the province was torn. The Seventh Report on Grievances had

become, since his appointment, the object of his constant perusal, and

the Reformers of the province crowded about him in the fond hope of

political redress. It was impossible, therefore, that Sir Francis should

fail to make some advances to the Reform party. This indeed he was most

anxious to do, although the tone of his opening address to his

parliament, in which he asked for a loyal support of himself, already

began to alienate the sympathy of those whose support he was most

anxious to secure. As a pledge, however, of his good intentions, he

determined to add three members to his executive council and to fill

their places from among the Reform party. The men upon whom his choice

fell were Robert Baldwin, Dr, John Rolph, a leader of the Mackenzie

faction, and John Henry Dunn who had filled the office of

receiver-general but had not been identified with either of the rival

parties. In a despatch addressed to the colonial secretary, the

lieutenant-governor speaks thus of Baldwin:— "After making every enquiry

in my power, I became of opinion that Mr. Robert Baldwin, advocate, a

gentleman already recommended to your Lordship by Sir John Colborne for

a seat in the legislative council, was the first individual I should

select, being highly respected for his moral character, being moderate

in his politics and possessing the esteem and confidence of all

parties."

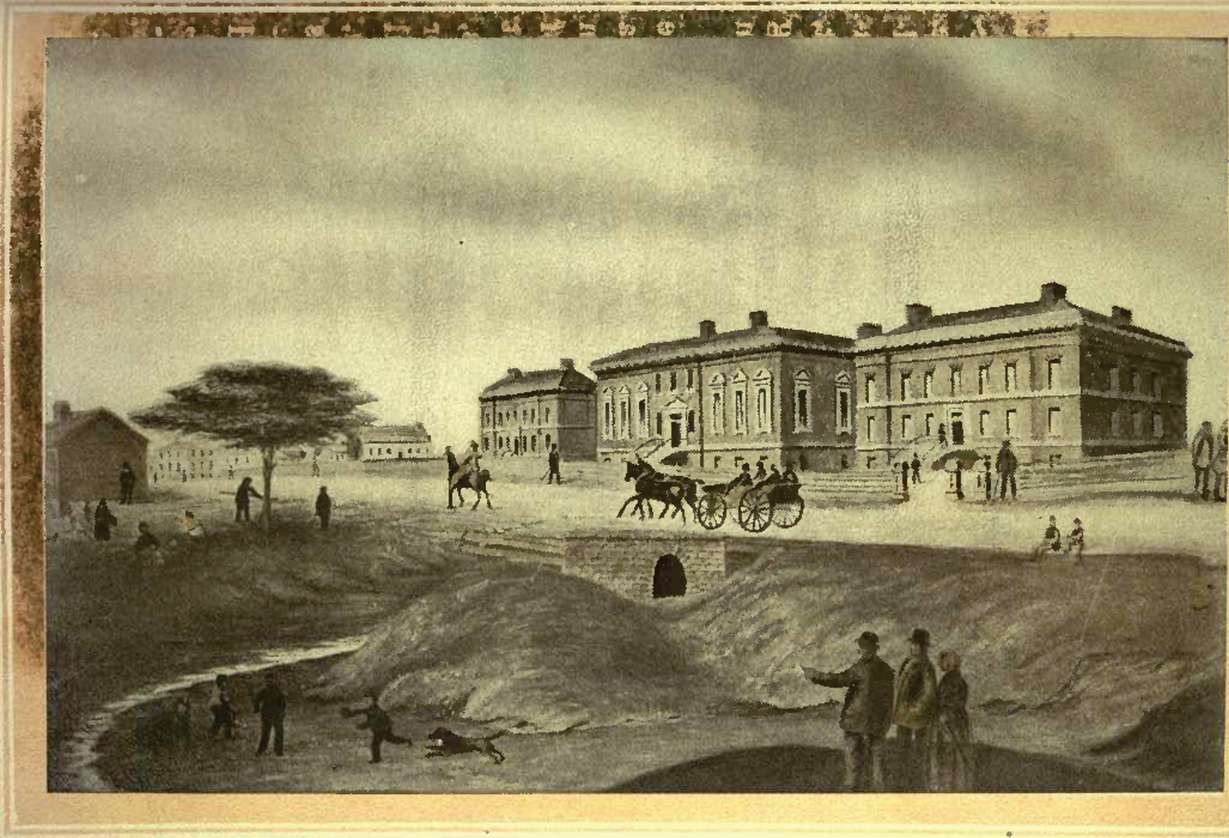

Parliament Buildings, Toronto, 1833

Now came a critical

moment in the history of the time. With a majority in the assembly and

with a proper control over the executive offices, the Reform party would

find themselves arrived at that goal of responsible government which had

been the object of their every effort. They conceived, nevertheless,

that the acceptance of office wras of no import or significance unless

it were conjoined with an actual control of the policy of the

administration. Such, however, was by no means the idea of Sir Francis

Head. The "smooth-faced insidious doctrine"2 of responsible government,

as he afterwards called it, and the self-effacement of the governor

which it implied, could commend itself but little to one who had

confessedly come to Canada as a "political physician" proposing to

rectify the troubled situation by his own administrative skill.

Interviews followed between Baldwin and Sir Francis Head, at Which the

former refused to hold office unless the remaining Tory members of the

executive, who were also legislative councillors,1 should be dismissed.

Baldwin indeed, suffering from Ihe domestic affliction he had just

sustained in the loss of his wife, appears to have been reluctant to

assume the cares of office. On reconsideration, however, the Reformers

decided to accept the positions offered and were duly appointed

(February 20th, 183G). It was, nevertheless, made quite clear to the

governor that Baldwin and his friends accepted office only on the

understanding that they must have his entire confidence. A letter,

written at this time by Bald-win to Peter Ferry, his father's friend and

fellow Reformer, accurately explains the situation and elucidates also

the full force of the "one idea" by which the writer was animated. "His

Excellency having done me the honour to send for me .... expressed

himself most desirous that I should afford him my assistance by joining

his executive council, assuring me that in the event of my acceding to

his proposals I should enjoy his full and entire confidence .... I

proceeded to state that .... I would not be performing my duty to my

sovereign or the country, if I .lid not with His Excellency's

permission, explain fully to His Excellency my views of the constitution

of the province and the change necessary in the practical administration

of it, particularly as I considered the delay in adopting this change as

the great and all absorbing grievance before which all others n my mind

sank into insignificance, and the remedy for which would most

effectually lead, and that in a constitutional way, to the redress of

every other grievance .... and that these desirable objects would be

accomplished without the least entrenching upon the just and necessary

pierogative of the Crown, which I consider, when administered by a

lieutenant-governor through the medium of a provincial ministry

responsible to the provincial parliament, to be an essential part of the

constitution of the province." Baldwin adds that the "call for an

elective legislative council which had been formally made from Lower

Canada, and which had been taken up and appeared likely to be responded

to in this province, was as distasteful to me as it could be to any

one."

The new ministry were

no sooner appointed than they found themselves in a quite impossible

position. Head had no intention of governing according to their advice.

On the contrary he proceeded at once to make official appointments from

among the ranks of their opponents, calling down thereby the censure of

the assembly. The new council now found themselves called to account by

the country for executive acts in which they had had no share. The 40

formal remonstrances which they addressed to the lieutenant'-governor

drew from him a direct denial of their cardinal principle of government.

"The lieutenant-governor maintains," they were informed, "that

responsibility to the people who are already represented in the House of

Assembly, is unconstitutional; that it is the duty of the council to

serve him, not them." To say this was, of course, to throw down the

gauntlet. The new ministers resigned at once (March 4th, 1836), and

henceforth there was war to the knife between the governor and the party

of Reform. The majority of the assembly, espousing the cause of the

outgoing ministers, refused to vote the appropriation of the moneys over

which it had control. Sir Francis had recourse to a dissolution (May

28th, 1836). In the general election which followed, he exerted himself

strenuously on the side of the Tories.1 To Lord Glenelg he denounced the

"low-bred antagonist democracy" which he felt it his duty to combat. In

an address issued to the electors of the Newcastle district, the voters

were told, "if you choose to dispute with me and live on bad terms with

the mother country, you will, to use a homely phrase, only quarrel with

your bread and butter." The Tories made desperate efforts. Large sums of

money were subscribed. The Anglican interest was enlisted on behalf of

the clergy reserves, the special landed provision for the Anglican

Church (under the Constitutional Act of 1791) out of which Sir John

Colborne, the preceding governor, had endowed forty-four rectories, a

policy to which the Reformers were bitterly opposed. The Methodists,

fearing to be carried to extremes, veered away from the party of

Reform.1 The latter, meanwhile, were not idle. Baldwin himself, indeed,

bad no share in the campaign, having sailed for England shortly after

his resignation, pursued by a letter from the irate governor to Lord

Glenelg in which lie was denounced as an agent of the revolutionary

party.

Meantime the Reform

party had organized a Constitutional Reform Society of Upper Canada

(.July I6th, 1830) of which Dr. William Baldwin was president and

Francis Hincks secretary. The programme of the society called for

"responsible advisers to the governor" and the "abolition of the

rectories established by Sir John Colborne." In the tumultuous election

which ensued, the governor and his party, with the aid of intimidation,

violence and fraud, carried the day. Sir Francis found himself supported

by a "bread and butter parliament," as the new assembly was christened

in memory of the Newcastle address. Henceforth the extreme party of the

Reformers lost hope of constitutional redress.

It is no part of the

present narrative to relate the story of the armed rebellion which

followed and which the subjects of the present biography had no share.

Mackenzie and his adherents now gathered the farmers of the colony into

revolutionary clubs. Messengers went back and forth to the malcontents

of Lower Canada. Vigilance committees were formed, and in secret hollows

of the upland and in the openings of the forest the yeomanry of the

countryside gathered at their nightly drill. Mackenzie passed to and fro

among the farmers as a harbinger of the coming storm. He composed and

printed a new and purified constitution for Upper Canada, blameless save

for its unconscionable length.1 An attack on Toronto, unprotected by

royal troops and offering a fair mark for capture, was planned for

December 7th, 1837. A veteran soldier, one Van Edmond who had been a

colonel under Napoleon, was made generalissimo of the rebel forces. The

whole affair ended in a fiasco. Rolpli, joint organizer of the revolt

with Mackenzie, fearing detection, hurriedly changed the date of the

rising to December 4th. The rebels gathering from the outlying country

moved in irregular bands to Montgomery's tavern, some three miles north

of the town, and waited in vain for the advent of sufficient members to

hazard an attack. In Toronto, for some days intense apprehension

reigned. The alarm bells rang, the citizens were hurriedly enrolled and

the onslaught of t he rebels was hourly expected. With the arrival of

support from the outside in the shape of a steamer from the town of

Hamilton with sixty men led by Colonel Allan MacNab, confidence was

renewed. More reinforcements arriving, the volunteer militia on a bright

December afternoon (December 7th, 1837) marched northward with drums

beating, colours flying, two small pieces of artillery following their

advance guard, and scattered the rebel forces iu headlong flight. The

armed insurrection, save for random attempts at invasion of the country

from the American frontier in the year following, had collapsed.

In the insurrectionary

movement, neither Baldwin nor Hincks, as already said, had any share.

The former who had now returned from England, did, however, play a

certain part in the exciting days of December, a part which m later days

bis political opponents wilfully misconstrued. Sir Francis Bond Head in

the disorder of the first alarm, whether from a sudden collapse of

nerves or with a shrewd idea of gaining time, was anxious to hold parley

with the rebels Robert Baldwin was hurriedly summoned to the governor

and despatched, along with Dr. John Rolph, under a flag of truce, to ask

of the rebels the reason of their appearance in arms. Baldwin and Rolph

rode out on horseback to Montgomery's tavern, where Mackenzie informed

them that the rebels wanted independence and that f Sir Francis Head

wished to communicate with them it must be done in writing. Rolph

meanwhile, who was himself one of the organizers of the revolt, entered

into private conversation with Samuel Lount changed later in Toronto for

his share in the rebellion), telling Lount. in an undertone to pay no

attention to the message. Baldwin returned to Toronto, but, finding that

the governor would put no message in writing, he again rode out to the

rebel camp and apprised Mackenzie of this fact. The peculiar nature of

this embassy and the known complicity of Rolph in the revolt, gave a

false colour in the minds of the malicious to Baldwin's conduct. By the

partisan press he was denounced as a rebel and a traitor. Even on the

floor of the Canadian parliament (October 13th, 1842) Sir Allan MacNab

did not scruple to taunt him with his share in the events of the revolt.

But it is beyond a doubt that, Baldwin had no complicity in the

rebellion, nor was his embassy anything more than a reluctant task

undertaken from a sense of public duty. -

While these affairs

were happening in Upper Canada, the insurrectionary movement in the

Lower Province had run a like disastrous course. The home government,

alarmed at the continued legislative deadlock, had ordered an

investigation at the hands of a special commission with a new

governor-general, Lord Gosford, (who arrived on August 23rd, 1835) at

its head. Gosford tried in vain the paths of peace, spoke the

malcontents fair and invited the leaders of the party to his t able. But

the assembly would nothing of Lord Gosford's overtures. Papineau denied

the powers of the imperial commissioners and boasted on the floor of the

assembly that an "epoch is approaching when America will give republics

to Europe."' The report of the commissioners (March, 1837) dissipated

the last hopes of constitutional redress. It condemned the principle of

an elective Upper House, declared that ministerial responsibility was

inadmissible, suggested that means should be found to elect a British

majority by altering the franchise, and recommended coercion in the last

resort. Following on the report came a series of resolutions moved in

the House of Commons by Lord John Russell, who declared in terms that

"an elective council for legislation and a responsible executive council

combined with a representative assembly would be quite incompatible with

the rightful iuter-relalionship of any colony with the mother country."

A bill was brought forward to dispose of the revenue of Lower Canada

without the consent of the assembly. After this the leader of the

movement saw no recourse but open rebellion. The peasanty of the

Montreal district, obedient to the call, took up arms. There was a

short, sharp struggle along the Richelieu, at the little villages of St.

Denis and St. Charles, and southward on the American frontier. Sir John

Colborne, hurriedly recalled to Canada to take command, crushed out the

revolt. Papineau fled to the United States, leaving to his followers

nothing but the memory of a lost cause.

Among those who had

warmly espoused the side of Reform m Lower Canada, but who, like Baldwin

and Hincks in the Upper Province, had had no sympathy with armed

insurrection, was Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine. LaFontaine, the son of a

farmer of Boucherville,1 in the county of Chambly, was born in October,

1807. His grandfather had been a member of the assembly of Lower Canada

from 179G until 1801. LaFontaine was educated at the College of

Montreal, where he distinguished himself as well by the natural

alertness of his mind as by a stubborn self-assertion which rendered

somewhat irksome to him the narrow, clerical discipline of the

institution. After studying law in the office of a Mr. Roy, LaFontaine

entered upon legal practice in the town of Montreal. Here in 18.31 he

married Mile. Adele Bert helot, daughter of a Lower Canadian advocate,

who died, however, a few years later leaving no children. Into the

political struggle of the time Lafontaine threw himself with great

activity. He was elected a member of the assembly for Terrebonne in 1830

and became a supporter, though not entirely a follower, of the turbulent

Papineau. Between the two French-Canadian leaders, there were from the

start marked differences both of opinion and of purpose. Papineau, aware

of the great influence of the clergy,2 was anxious to conciliate their

interests and enlist their support. LaFontaine, bold if not heterodox in

his views, stood out as the champion against the traditional dominance

of the priesthood. Although LaFontaine had no sympathy whatever with

violent measures, he distinguished himself during the constitutional

agitation as one of the boldest of the agitators. His first action in

the legislature was to second a motion for the refusal of supplies, and

throughout the years preceding the rebellion, both from his place in

parliament and in the press, he exerted himself unceasingly in the cause

of the popular party. When the storm broke in 1837, he endeavoured in

vain to dissuade his fellow-countrymen from taking up arms. A few days

after the skirmishes on the Richelieu (December, 1837) he went from

Montreal to Quebec to beg Lord Gosford to call a meeting of the

legislature with a view to prevent further violence. On the refusal of

the governor to do so, LaFontaine took ship for England. Feaung,

however, that his complicity in the agitation preceding the Canadian

revolt might lead to his arrest, he fled from England and spent some

little time in France. Thence he returned to Canada in May, 1838. This

was the moment when Sir .John Colborne was busily employed in

extinguishing the still smouldering ashes of revolt. Wholesale arrests

of supposed sympathizers were made. An ordinance passed by Sir John

Colborne and his special council, appointed under the Act suspending the

constitution of Lower Canada,1 declared the Habeas Corpus Act to be

without force in the province. The prisons were soon filled to

overflowing. Among those arrested was Ilippolyte LaFontaine, an arrest

for which legal grounds were altogether lacking. LaFontaine, since his

return to Canada, had written a letter to Girouard, one of his

associates m the constitutional agitation, in regard to the frontier

disturbances of 1838, recommending, in what was clearly and evidently an

ironical Vein, a continuance of the insurrection. On the strength of

this and on the ground of his having been notorious as a leader of the

French-Canadian faction, he was arrested on November 7th, 1838, and

imprisoned at Montreal. The evident insufficiency of the charges against

him, led shortly to his release without trial.1 The collapse of the

rebellion, the flight of Papineau and O'Callaghan. and the arrest of

Wolfred Nelson and many other leaders, naturally induced the despairing

people of Lower Canada to look for guidance to the moderate members of

the party who had realized from the first the folly of armed revolt. In

the period of reconstruction which now followed under the rule of Lord

Durham and Lord Sydenham, LaFontaine was recognized as the leader of the

national Reform party of Lower Canada, energetic in its protest against

the proposed system of union and British preponderance but determined by

constitutional means, when the union was forced upon them, to turn it to

account in the interest of French Canada. |