|

THE sudden death of

Lord Sydenham occasioned an interregnum in the government of the

province, during which time the administration was carried on under Sir

Richard Jackson, commander of Her Majesty's forces in Canada. On October

7th, 1841, a new governor-general was appointed in the person of Sir

Charles Bagot, who arrived at Kingston on Monday, January 10th, 1842.

The news of his appointment had been the subject of a premature

jubilation on the part of the thorough-going Tories of the MacNab

faction. The nominee of the Tory government of Sir Robert Peel, and

himself known for a Tory of the old school, Sir Charles was expected to

restore to Canada an atmosphere of official conservatism which should

recall the serener days of the Family Compact. The sequel showed that

Sir Charles was prepared to do nothing of the kind. He was, indeed, a

Tory, but his long parliamentary and diplomatic training had stood him

in good stead. As an undersecretary of state tor foreign affairs and on

diplomatic missions at Paris, Washington and St. Petersburg, he had

learned the value of the ways of peace. At the Hague, whither he had

been sent in connection with the recent disruption of the kingdom of the

Netherlands, he had already had to face the problem of rival religions

and hostile races. The natural affability and kindness of his

temperament, combined with the enlightened wisdom of advancing years,

led him to seek rather to conciliate existing differences than to

inflame anew the smouldering embers of partisan animosity. Devoid of the

personal egotism which had so often converted colonial governors into

"domineering proconsuls," Sir Charles was willing to entrust the task of

practical government to the hands most able to undertake it. For the

role of pacificator, the new governor-general was well suited. His

distinguished bearing and upright can; age. and the ease with which he

mingled with all classes of colonial society rapidly assured hnn in the

province a personal esteem destined greatly to facilitate that

conciliation of rival parties which it was his hope to accomplish.

It only remained for

Bagot to find, among the political groups which divided his parliament,

a party, or a union of parties, strong enough to en able him to carry on

the government on these lines. As the parliament was not summoned for

eight months after his arrival, Sir Charles had ample time to look about

him and to consider the political situation which lie was called upon to

face. Visits to Toronto, Montreal and Quebec brought him into contact

With the political leaders of the hour, and enabled him to realize that,

with the ministry as it at the moment existed, it would not be possible

long to carry on the government. Indeed the Draper ministry had owed its

continued existence solely to the recognized value of certain of the

measures which it had initiated. It had enjoyed a sort of political

armistice, at the close of which a renewed and triumphant onslaught of

its opponents might naturally be expected. In particular the new

governor realized that it would be impossible to carry on the government

of the country without an adequate support from the French-Canadians.

lie made it, therefore, his aim from the outset to adopt towards them an

attitude of friendliness and confidence. Several important appointments

to office were made from among their ranks. Judge Vallieres, one of Sir

John Colbome's former antagonists, was made chief-iustiee of Montreal;

Dr. Meilleur, a French-Canadian scholar of distinction, became

superintendent of public instruction. As a result of this policy was

greeted in Lower Canada with signal enthusiasm and his memory7 has still

an honoured place in the annals of the province.

Meantime it had become

evident even to Mr. Draper that some reconstruction of the ministry and

some decided modification of its policy were urgently demanded. French

Canada was still loud in its complaints against its lack of proper

representation in the cabinet, against the injustice of the present

electoral divisions, and against local government by appointed officers.

"The government," said he Canadian, a leading journal in the Reform

interest,, " may keep us in a state of political inferiority, it may rob

us, it may oppress us. It has the support of an army and of the whole

power of the empire to enable it to do so. But never will we ourselves

give it our support in its attempt to enslave and degrade us." The tone

of the province was clearly seen in the bye-elections which took place

during the recess of parliament. D. B. Papineau, a brother of the ex-led

leader, was elected for Ottawa, James Leslie, who had been one of the

victims of the election frauds of 1841, was elected for Vercheres. Most

significant of all was the return to parliament of Louis Hippolyte

IiaFontaine. Baldwin, it will be remembered, had been elected in 1841

for two constituencies, Hastings and the fourth riding of York. He had

accepted the seat for Hastings, and the constituency of York was thereby

without a representative. He proposed to his constituents that they

should bear witness to the reality of the Anglo-French Reform alliance

by electing IiaFontaine as their representative. LaFontaine accepted

with cordiality the proposal of his ally. "I cannot but regard such a

generous and liberal otfer," he wrote in answer to the formal invitation

from the Reform committee of the ruling, "as a positive and express

condemnation, on the part of the freeholders, of the gross injustice

done to several Lower Canadian constituencies, which* in reality, have

been deprived of their elective franchise, and which, in consequence of

violence, riots and bloodshed, are now represented in the united

parliament by men in whom they place no confidence."

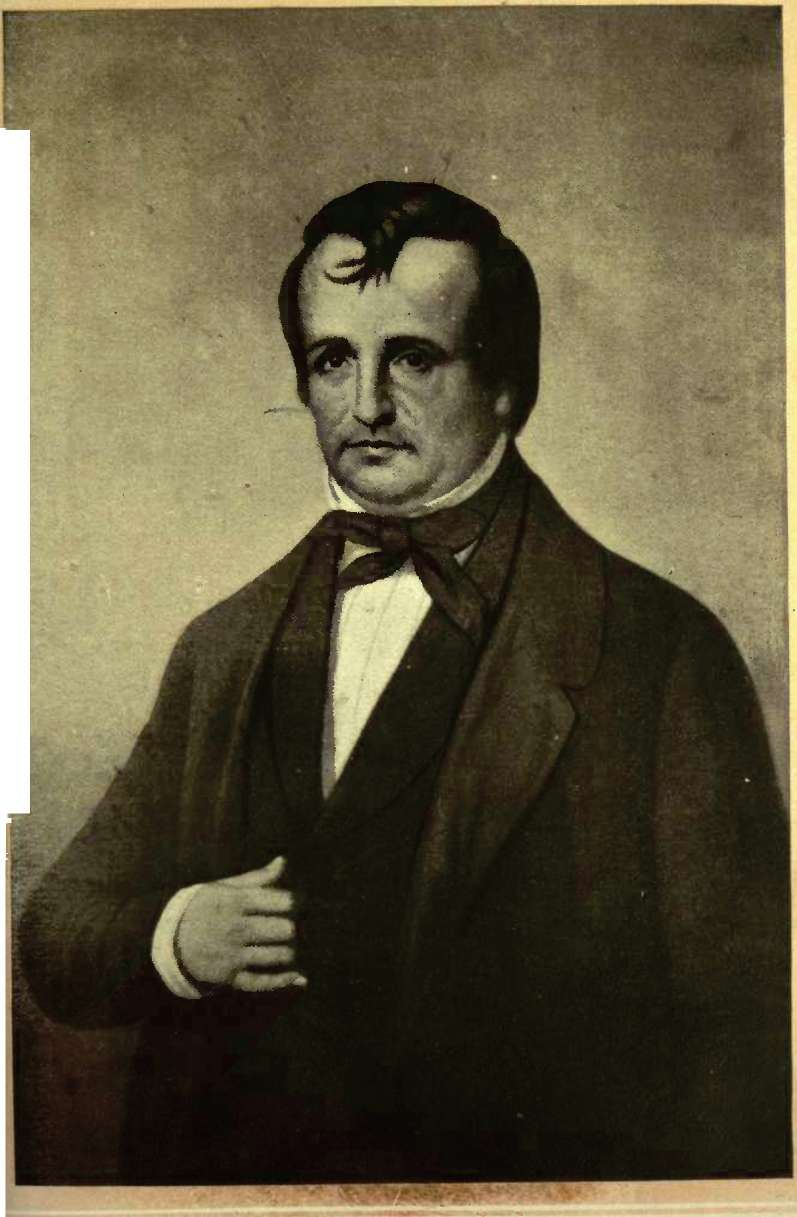

Sir Louis H. LaFontaine

To his new constituency

LaFontaine issued an address in which he urged the need of cooperation

between the French and English parties. "Apart from the considerations

of social order, from the love of peace and political freedom, our

common interests would alone establish sympathies which, sooner or

later, must have rendered the mutual cooperation of the mass of the two

populations necessary to the march of government. . . . The political

contest commenced at the last session has resulted in a thorough union

in parliament between the members who represent the majority of both

peoples. That union secures to the provincial government solid support

in carrying out those measures which are required to establish peace and

contentment." LaFontaine's candidacy was successful and he was elected

in September, 1841, by a majority of two hundred and ten votes.

It was the design of

Bagot to meet the impending difficulties of the situation, before the

meeting of parliament, by such a reconstruction of his ministry as

should convert it into a coalition in which all parties might be

represented. To men of moderate views, of the type of Sir Charles Bagot,

there is an especial fascination in the idea of a political coalition.

To subordinate the petty differences of party animosity to the broader

considerations of national welfare, is a task so congenial to their own

temperament that they do not realize how difficult it is for others. To

gather into a single happy family the radical and the reactionary, the

clerical and the secularist, is a hope as tempting as it is fatuous. The

initial success which had attended Bagot's efforts, the enthusiasm of

his reception in French Canada, concealed for the moment the

difficulties of the peaceful reunion which he proposed. At Montreal the

governor had been received by a "procession upwards of a mile in length,

while the hundred banners and flags which fluttered in the gentle

breeze, together with the animating strains of martial music, formed a

tout ememble which had never before been witnessed in Canada."

"The milleniuin," wrote

a British correspondent, a month or two later, "has certainly arrived.

Lord Ashburton has settled all difficulties between John Bull and

Brother Jonathan, and the lion and the lamb are seen lying down together

in Sir Charles Bagot's cabinet." This last allusion referred to the

elevation of Franc's Ilincks and Henry Sherwood to executive office. On

June 9th, 1842, Hineks was given the post of inspector-general. Previous

to the union this position (in each province) had been of a somewhat

routine character, the chief duties of its incumbent being to vouch for

the correctness of the warrants issued on the receiver-general.1 But

even in Sydenham's time it was intended that the office should be

converted into what might be called a Ministry of finance, and that the

inspector-general should hold a seat in the legislature as the official

exponent of the financial policy of the government. The voluntary

retirement of the Hon. John Macauley of Kingston, inspector-general for

Upper Canada, had made an opening, and Hincks was accordingly given the

position of inspector-general of Canada, while the former incumbent of

the office in Lower Canada was made deputy-inspector for the united

provinces.

It had been charged

against Hincks that, even during the preceding session of the

parliament, the prospect of this office had been held out as a bait to

allure him from his allegiance to the Reformers. But according to his

own statement no approaches of this kind were made to him at all during

the year 1841. Nor did he intend, in accepting a seat in the executive

council, which was to accompany the inspectorship, to forego any of his

previous principles. In his address to his Oxford constituents on the

occasion of his reelection on appointment to office, he said: "I have

accepted office without the slightest compromise of my well-known

political principles, and I shall not continue to hold it unless the

administration with which I am connected shall be supported by the

public opinion of the country." Nevertheless the bitter comments of the

rival factions on Hincks's appointment showed already the

impossibilities of a general reconciliation. " The appointment of Mr.

Hincks to the lucrative and important office of inspector-general," said

a contemporary journalist,1 "has been received with strong expressions

of disapproval by the great bulk of the loyal party of the province.. .

. Mr. Hincks has long conducted a journal which has been accused of

ministering sedition to r.ts readers, and at the breaking out of

Mackenzie's rebellion he stood with his arms folded, rendering no

assistance towards quelling the atrocious attempt of that mountebank.

... It is for these reasons that t he honours now bestowed on him are so

objectionable to a great part of the people." It will be noted that both

now and later it was an article of faith with the Tories that they were

the only loyal part of the population, a fiction which rendered any

political compromise with them all the more difficult to effect.

In order to offset the

appointment of Hineks, Bagot at the same time offered the post of

solicitor*-general for Upper Canada to Cartwright, a leading member of

the MacNab party. Cartwright declined the office, and forwarded to Sir

Charles Bagot a letter in explanation of his refusal. The recent

appointment, he said, had been viewed with disapproval by the

Conservative party to which he belonged. He construed it as an evidence

that the government was indifferent to the political principles of its

supporters, even when their principles were unfriendly to British

supremacy. The cry for responsible government was a danger to the

country, and was a request incompatible with the position of Canada as a

British colony. Of this dangerous movement, Mr. Hincks had been the

"apologist." He had been the defender of Papineau and Mackenzie up to

the very moment of the rebellion. To go into a government with "this

individual" would ruin Mr. Cartwright's character as a public man.1 As

Mr. Cartwright's objections appeared invincible, the post was offered to

one of his fellow Conservatives, Henry Sherwood, a lawyer of Toronto.

Mr. Sherwood, contrary to the expectation of his party, accepted the

office, entering upon his duties in July, 1842. The ministry was

therefore (in the month of August, 1842) of a decidedly multi-coloured

complexion, containing as it did, representatives of the Tories, the

Reformers, and of the old council. But it was the intention of Bagot to

carry his principle of combination still further, and to enlist, if

possible, the services of the two men most influential in the country,

Baldwin and LaFontaine. Of LaFontaine's support the governor felt a

particular need.

The ministry contained

no French-Canadians, and of the special offices which were concerned

exclusively with the affairs of Lower Canada, one (the office of

solicitor-general) had been rendered vacant by the elevation of Mr. Day

to the bench, while the incumbent of another (Ogden, the

attorney-general) was absent in England. It was becoming clear that,

unless a reconstruction could be effected, the present ministry would be

left almost unsupported in the House. Mr. Draper seems to have accepted

the situation with philosophic resignation. He was quite ready, if need

be, to resign his own place, and he harboured no delusions about his

ability to carry on the government with inadequate support. The meeting

of parliament at Kingston (September 8th, 1842) was made the occasion of

an attempt on the part of the governor to complete his system of

coalition. His speech from the throne, while referring to the prosperous

financial position of the government and the rapid progress of the

public works undertaken, expressed an ardent wish that "a spirit of

moderation and harmony might, animate the counsels of the parliament."

The debate on the address n answer to the speech was fixed for Friday,

September 13th. On that afternoon the governor, who had already been n

personal consultation with LaFontaine, wrote to him in the following

terms:—

"Having taken into my

most earnest and anxious consideration the conversation which passed

between us, I find my desire to invite to the aid of, and cordial

cooperation Math my government the population of French origin in tins

province, unabated. ... I have, therefore, come, not without difficulty,

to the conclusion that, for such an object, I will consent to the

retirement of the attorney-general, Mr. Ogden, from the office which he

now holds, upon its being distinctly understood that a provision will be

made for him commensurate with his long and faithful services. Upon his

retirement I am prepared to offer to you the situation of

attorney-general for Lower Canada with a seat in my executive council. .

. .

"Mr. Baldwin's

differences with the government have arisen chiefly from his desire to

act in concert with the representatives of the French portion of the

population, and, as I hope these differences are now happily removed, I

shall be willing to avail myself of this service. Mr. Draper has

tendered me the resignation of his office. I shall always regret the

loss of such assistance as he has uniformly afforded me, and I 'shall

feel the imperative obligation of considering his claims upon the

government, whenever an opportunity may offer of adequately

acknowledging them. . . .

"From, my knowledge of

the sentiments entertained by all the gentlemen who now compose my

constitutional advisers, I see no reason to doubt that a strong and

united council might be formed on the basis of this proposition. In this

persuasion I have gone to the utmost length to meet and even to surpass

your demands, and i f, after such an overture, I shall find that my

efforts to secure the: political tranquillity of the country are

unsuccessful, I shall at least have the satisfaction of feeling that I

have exhausted all the means which the most anxious desire to accomplish

the great obiect has enabled me to devise.

" I have the honour,

etc,

"C. Bagot."

The promise was given

in the same letter that the position of solicitor-general for Lower

Canada should be filled according to LaFontame's nomination, provided

only that the person nominated was British. The conimissionership of

Crown lands was likewise to be offered to M. Girouard, a former

associate and friend of LaFontaine during the constitutional struggle

preceding the rebellion. At the same time a pension was to be granted to

Mr. Davidson, the previous commissioner, an old servant of the

government. That the proposal thus made went a long way towards meeting

the demands of the Reform party can be seen by reading the comments on

it in the Tory press, when the letter was subsequently read out in the

assembly by Mr. Draper as a proof of the intractable attitude of the

Reformers. " Incredible and humiliating as it may appear," said the

Toronto Church, "it was really written by Sir Charles Bagot to Mr.

LaFontaine. ... A Radical ministry cannot last long. Loyal men need not

despair; they have G-od on their .tide. We must begin to agitate for a

dissolution of the union between Upper and Lower Canada, or a federal

union of all the British North American provinces." It will be seen from

this that the exasperated Tories claimed a monopoly, not only of loyalty

to the Crown, but even of the sheltering protection of Providence.

Flattering as was Sir

Charles Bagot's proposal, LaFontaine, after hurried consultation with

his future colleague, did not see fit to accept it. It had been the aim

of the Reform leaders not merely to obtain office for themselves

personally but to force a resignation of the whole ministry, to be

followed by a cabinet reconstruction in due form. Even with Draper

absent, there were several members of the existing administration,

notably Sherwood, the Tory solicitor-general just appointed, with whom

they would find it difficult to cooperate. To accept the responsibility

of providing pensions for Ogden and Davidson seemed to LaFontaine,

wrongly perhaps, a bad constitutional precedent. The suggestion of

giving pensions was not indeed without defence, under the circumstances.

Davidson was an old public servant who had taken no active part in

politics, and who had no wish to continue to hold an office which was

now to be made a subject of party appointment and dismissal.1 The office

held by Ogden had also been non-political at the time of his assuming

it. But a further objection to the proposal lay in the fact that the

united Reformers were 5n complete command of the situation, and could

afford to insist on better terms of' entry upon office than those

offered by Sir Charles Bagot.

Foiled in the plan of

friendly reconstruction, there was nothing for it for the government but

to fight its way with the address as best it might. The resolutions fox

the adoption of a cordial response to the speech from the throne were

the signal for a debate of unusual interest and excitement, during which

the galleries of the legislative chambers were packed With eager

listeners who felt that the fate not only of the government, but of the

system of government, hung on the issue. The newspapers of the day

testify to the intense interest occasioned by the prospect of the

approaching trial of strength. This afternoon," writes the Toronto

Herald of September 13th, "the great battle commenced. The war is even

now being carried into the enemy's camp—excitement increases—members

rave—the people wax furious —and where it will end no one can guess." "

The House was so crowded," complained a local journalist, " that we were

unable to obtain any space for writing in, and had to rely on our

recollection for an abstract of the day's proceedings."

Mr. Draper was too keen

a fighter to surrender tamely and without a struggle. He addressed the

House in what was called by the Kingston Chronicle, "one of the most

splendid and eloquent speeches we have ever heard." He submitted to the

consideration of the assembly an account of the unsuccessful attempt to

obtain the services of LaFontaine in the government. It had been

recognized, he said, that it was absolutely right that the gentlemen

representing the population of French Canada should have a share in the

administration of affairs. It had not escaped attention that an alliance

had been formed between the representatives of French Canada and the

honourable member for Hastings. When the government had opened

negotiations wit h the honourable member for the fourth riding of York

(Mr. LaFontaine), it had appeared that the inclusion of Mr. Baldwin in

the government was made a sine qua non. He (Mr. Draper) had felt that he

could not remain in the council if Mr. Baldwin were brought into it. It

was for this reason that he had tendered his resignation. Mr. Draper

then read aloud the governor's letter to LaFontaine. On what grounds His

Excellency's proposal had been declined he would leave to the honourable

members opposite to explain.

LaFontaine and Baldwin

both spoke in answer. LaFontaine spoke in French, At the opening of his

speech he was interrupted by a member asking him to speak in English.

LaFontaine refused. "Even were I as familiar with the English as with

the French language," he said* "I should none the less make my first

speech in the language of my French-Canadian compatriots, were it only

to enter my solemn protest against the cruel injustice of that part of

the Act of Union which seeks to proscribe the mother tongue of half the

population of Canada." In the course of his speech I/a Fontaine dwelt

upon the unfair position in which French Canada was placed and its lack

of representation in the cabinet. He had no wish for office unless his

acceptance of it should mean the introduction of a new regime. In

default of that, " in the state of enslavement in which the iron hand of

Lord Sydenham sought to hold the people of French Canada, in the

presence of actual facts which still bespeak that purpose, he had (in

refusing), but one duty to fulfil,--that of maintaining that personal

honour which has distinguished his compatriots and to which their most

embittered enemies are compelled to do homage."'

Baldwin, following

LaFontaine with an amendment to the address embodying a declaration of

want of confidence, was able to feel that his hour of triumph had come.

The government at the close of the last session had acquiesced in the

resolutions affirming the principle of responsible 128 government; these

they must now repudiate or inevitably find themselves out of office.

Baldwin could scarcely be called an eloquent speaker. His language was

often cumbrous and was devoid of imagery. But in moments such as the

present he was able to present a clear case with overwhelming force. He

challenged the government to abide by the principle which they had

avowed. In that principle lay the future safety of the imperial

connection and the union of the Canadas. "I will never yield my desire,"

he said, '* to preserve the connection between this and the mother

country : and although it is said a period must arrive demanding a

separation, I, for my part, with the principle that has now been avowed

being acted on, cannot subscribe to that opinion. If a conciliatory

policy is adopted towards all the people of this country, such an

opinion could have no existence. I was, and still am. an advocate of the

union of the provinces, but an advocate not of a union of parchment, but

a union of hearts and of free born men."

If, the speaker

continued, the ministry believed it but an act of justice to the LowTer

Canadians to call some of their representatives to the councils of their

sovereign's representative, why had they kept this conviction pent up In

their own minds without the manliness to give it effect t They admitted

the justice of the principle but had not the manliness to give it

effect. Out of their own mouths they stood convicted. Other members

joined in the debate. Aylwin denounced the government m unstinted terms.

The letter to LaFontaine, he said, was a trick. It was intended to

increase discord. Mr. Draper had said that he was unwilling to remain in

office as a colleague of Mr. Baldwin. He could not act with the master,

but he had no objection to acting with the disciple. This sneering

allusion to Hincks provoked from that member an embittered denial of the

aptness of the phrase. He had never been, he said, a disciple of Robert

Baldwin; the great question on which they had agreed, and for which they

had acted together, had been responsible government; that was near

settled and conceded. The policy of the administration had been worthy

of support, and he had supported it.

The attack thus opened

on the government waged hotly through the sitting of the afternoon and

evening. Bartlie of Yamaska, Viger and others joined in the onslaught.

When the debate was at last adjourned, a little before midnight, it was

plain to all that if a vote should be taken on Baldwin's amendment the

government must inevitably succumb. It was in vain that Sullivan in the

Upper House had undertaken the defence of the government with his usual

brilliance and power; in vain that he had tried to show that the

Reformers were merely a party of obstruction, bent on impeding the

legitimate operation of government for their 130 own selfish ends. "Are

we," he cried. "to carry on the government fairly and upon liberal

principles, or by dint of miserable majorities,? by the latter or by the

united acclamations of the people? We wish to know, in fact, whether

there is sufficient patriotism to allow us to work for the good of the

people."

The argument against

miserable majorities, whatever it might mean to a philosopher, was

powerless to meet the situation or to save the government from its

imminent defeat, Great, therefore, was the expectation of the public for

a renewal of the struggle on the following day. The halls and galleries

of the legislature were packed with an expectant audience. All the

greater was the surprise of the spectators to find that the storm which

had raged so fiercely in the House had now suddenly and entirely

subsided. Very obviously something had happened. The members of the

assembly, who yesterday had appeared instinct with an eager intentness,

now sat with quiet composure in their luxurious chairs of "green moreen,"

meditating in silence or even chatting and joking with their fellows.

There was for a moment a thrill of expectation in the audience when

Hineks arose; he, if any one, might be expected, with liis incisive

speech and telling directness, to precipitate an encounter. Rut, to the

disappointment of the listening crowd n the galleries, the

inspector-general merely moved that the debate on Mr. Baldwin's

amendment, should be postponed till Friday. The quiet acceptance of this

proposal by the House showed that the majority of the members were aware

of its meaning. The government, unable to face the rising storm of

opposition, had capitulated. Mr. Draper's resignation was again to be

handed in, and a general reconstruction of the ministry was to be

effected. Some few of the members ventured an immediate protest. Dr.

Dunlop, an "independent" member for Huron, known as "Tiger Dunlop,"

denounced the contemplated adjustment. The political transformation that

seemed about to be accomplished would introduce, he said, within a space

of twenty.-, four hours, changes as extraordinary as those witnessed by

Rip Van Winkle after a lapse of twenty years. The new ministry that was

in the making would be as composite as Nebuchadnezzar's dream; he would

not be invidious enough to say who would be the head of gold or who the

feet of brass, but the greater part of it he feared would be of dirt.

In despite, however, of

Dr. Dunlop's sallies and the loud outcry of the Tory press, the proposed

arrangement was carried to its completion. Baldwin withdrew his

amendment; Mr. Draper resigned, and LaFontaine and his colleague entered

upon office. The change effected was not a complete change of cabinet,

inasmuch as Hincks, Ivillaly, Sullivan and three others still remained

in office. As Ilincks has pointed out, the name, " LaFontaine-Baldwin

ministry" commonly applied to the new executive group is therefore

inaccurate.1 Sullivan was in reality the senior member of the council.

But in the wider sense of the term the designation, "LaFontame-Baldwin

ministry." indicates the essential principle of its reconstruction, and,

as a matter of historical nomenclature, has long met with a general

acceptance. The formation of the ministry involved a certain element of

compromise. The disputed question of the pensions was left as a matter

of individual voting, and in the sequel was satisfactorily arranged,

Ogden being given an imperial appointment and Davidson a collectorship

of customs. It was not, according to Hineks,2 definitely and formally

stipulated that the ministers left over from the old ministry should

retain their seats on condition of conforming to the policy of then' new

chiefs. But, with the exception of Sullivan, their known opinions were

such as to render this conformity more or less a matter of course. The

ministry as finally constituted —the change occupied two or three weeks

—was as follows :—

Canada; Robert Baldwin,

attorney-general for Upper Canada; R. B. Sullivan, president of the

council; J. H. Dunn, receiver-general; Dominick Daly, provincial

secretary for Lower Canada; S. B. Harrison, provincial secretary for

Upper Canada; II. II. Killaly, president of the department of public

works; F. Hincks, inspector-general of public accounts ; T. C. Aylwin,

solicitor-general for Lower Canada; J. E. Small, solicitor-general for

Upper Canada; A. N. Morin, commissioner of Crown lands. The last named

office had been declined by Mr. Girouard, whose name had been mentioned

in Sir Charles Bagot's letter, and was, at LaFontaine's suggestion,

conferred upon Morin, his most intimate friend and political associate.

The incoming ministers,

in accordance with parliamentary practice, now resigned their seats and

submitted themselves to their constituents for reelection. The election

of LaFontaine in what the Tories called his ''rotten borough" of the

fourth riding of York, was an easy matter. Baldwin, on the other hand,

encountered a stubborn opposition. The following newspaper extracts

(both taken, it need hardly lie said, from journals opposed to the new

ministry) may give some idea of the elections of the period and the

virulence of the party politics of the day.

"The Hastings election

commenced on Monday'. At half past ten the speeches began and lasted

till three. Although Mr. Baldwin came in with a large procession and Mr.

Murney had none, yet the latter was listened to with extreme attention,

and spoke admirably. Mr. Baldwin could not be heard half the time, there

was incessant talking while he spoke. At five o'clock 011 Tuesday

evening the poll stood thus:—Murney, 130; Baldwin, 124. The poll does

not close till Saturday night. Let every loyal man consider that on his

single vote the election may depend, and let him immediately hasten and

record it for Murney.

"The fourth riding

election commenced on Monday. William Roe. Esq., a popular and loyal

man. resident at Newmarket, opposes Mr. LaFontaine* The poll is held at

David-town (fit place!). By the last accounts the votes stood thus:—LaFontaine,

191 ; Roe, 71. Mr. Roe was recovering his lost ground and will fight

manfully to the last. Every out-voter should repair to his aid. Saturday

will now be too late."

"The Hastings election

has terminated in favour of Mr. Murney. The numbers at the last were:—

Murney, 482 ; Baldwin. 433. A number of shanty-men having no votes were

hired by Mr. Baldwin's party to create a disturbance. They did so, and

ill treated Mr. Murney's supporters. The latter, however, rallied and

drove their dastardly assailants from the field. Two companies of the

23rd Regiment were sent from Kingston to keep the peace, and polling was

most unjustly discontinued for one day. The returning officer, Mr.

Sheriff Moodie, is described to us, on good authority, as having

entirely identified himself with the Baldwin party. He has made such a

return as will prevent Mr. Murney from taking his seat, and no doubt the

tyrannical and anti-British majority in the House will sustain him n any

injustice, especially if t be exceedingly glaring."

A less prejudiced

journal1 gives the following more impartial account of the same

proceedings:— "On Wednesday, (October 5th), t appears that bodies of

voters, armed with bludgeons, swords, and firearms, generally consisting

of men who had no votes but attached to opposite parties, alternately

succeeded in driving the voters of Mr. Baldwin and Mr. Murney from the

polls. . . . One man had his arm nearly cut off by a stroke of a sword,

and two others are not expected to live from the blows they have

received. All the persons injured whom we have mentioned were supporters

of Mr. Baldwin, but we understand that the riotous proceedings were

about as great on the one side as the other."

Baldwin was of course

compelled to seek another constituency! The election n the second riding

of York had been declared void and Baldwin was put up as a candidate by

well-intentioned friends, in despite of the fact that he had already

arranged to offer himself to a Lower Canadian constituency. The upshot

was that Baldwin, who made no canvass of the York electors, was again

beaten. But his allies m French Canada were now only too anxious to make

a fitting return for his action in this respect towards LaFontaine. For

the debt of gratitude incurred, an obvious means of repayment suggested

itself. Several French-Canadian members offered to make way for the

associate of their leader. Baldwin accepted the offer of Mr. Borne, the

member for Rimouski, for which constituency he was finally elected

(January 30th, 1843), but not until after the session had closed.

The incoming of the

first LaFontaine-Baldwin ministry as thus constituted, offers an

epoch-making date in the constitutional history of Canada. It may with

reason be considered the first Canadian cabinet,1 in which the principle

of colonial self-government was embodied. This is not to say that it

marks the establishment of responsible government in Canada, for to

assign a date to that might be a matter of some controversy. Durham had

recommended responsible government; Russell in his celebrated despatch

had indicated, somewhat vaguely, perhaps, the sanction of the home

government to its adoption; Sydenham had evaded, if not denied, it. Even

after this date, as will appear in the sequel, Metcalfe refused to

accept it as the fundamental principle of Canadian government. Not until

the coming of Lord Elgin can it be said that responsible government was

recognized on both sides of the Atlantic as a permanent and essential

part of the administration of the province. But it remains true that in

this LaForitaiue-Baldwin ministry we find for the first time a cabinet

deliberately constituted as the delegates of the representatives of the

people, and taking office under a governor willing to accept their

advice as his constitutional guide m the government of the country.

The distinct advance

that was thus made in the political evolution of the British colonial

system becomes more apparent upon a nearer view of the attendant

circumstances of the hour. At the present day the people of Britain and

the British colonies have become so accustomed to the peaceful operation

of cabinet government that they are inclined to take it for granted as

an altogether normal phenomenon, the possibility and the utility of

which are self-evident. It is no longer realized that responsible

government, hke the wider principle of government by majority rule,

rests after all upon convention. Unless and until the minority of a

country are willing to acquiesce in the control of the majority, the

whole system of vote counting and legislation based on it is impossible.

In a community where the voters defeated at the polls resort to violence

and rebellion, majority rule loses its political significance, for this

significance lies in the fact that it has become a general political

habit of the community to accept the decision of the majority of

themselves. On this presumed consensus, this general agreement to submit

if voted down, rests the fabric of modern democratic government, The

same is true, also, of the particular form of democratic rule known as

cabinet or responsible government: t presupposes that the beaten party

recognize the political right of their conquerors to take office; that

they will not consider that the whole system of government has broken

down merely because they have been voted out of power; nor meditate a

resort to violent measures, as if the political victory of their

opponents had dissolved the general bonds of allegiance. So much has

this party acquiescence become in our day the traditional political

habit, that m British, self-governing countries His Majesty's ministers

and His Majesty's Opposition circulate n and out of office with decorous

alternation, each side recognizing in the other an institution necessary

to its own existence. Rut at the period of which we speak the case was

different,. To the thorough-going Tories the admission to office of

LaFontaine, Baldwin and their adherents seemed a political crime.

Loyalty raised its hands in pious horror at the sight of a ministry whom

it persisted iii associating with the lost cause of rebellion and

sedition, and one of whose two leaders was under the permanent stigma

attaching to an alien name and descent. Even the traditional Up service

due to colonial governors was forgotten, and the Tory press openly

denounced Bagot as a feeble-minded man led astray by a clique of

seditious and irresponsible advisers.

The journals of the

autumn of 1842 are filled with denunciations of the new government. "If

the events of the past few weeks," wrote the Montreal Crazette, "are to

be taken as a presage of the future —and who doubts it?—Lower Canada is

no longer a place of sojourn for British colonists. A change has come

over the spirit of our dream in the last few weeks, so sudden, so

passing strange, that we have been scarcely able to comprehend its

nature and extent. By degrees, however, the appalling truth develops

itself. Every post from Kingston confirms the fact that the British

party has been deliberately handed over to the vindictive disposition of

a French mob, whose first efforts are directed towards the abrogation of

those lawrs which protect property and promote improvement. Every step

in the way of legislation since the 8th ultimate, has been a step

backward, and the heel falls each time, with insulting ingenuity, on the

necks of the British. ' Coming events cast their shadows before.' They

are cast broadly and ominously, almost assuming in our sad and most

reluctant eyes, the mysterious characters of sacred writ—."

The Montreal Transcript

was even more outspoken in its denunciation. "To a governor without any

opinion of his own and ready to veer about at every breath of

opposition, no worse field could have been presented than Canada. Were

Ilis Excellency only resolute, the presence of three or four men in 1 is

cabinet could not avail to render him powerless and passive. But from

the moment that the patronage of the Crown was surrendered, ui such an

unexampled manner, to such men—from the moment a scat in the cabinet was

offered and pressed upon a man1 who had fought in open rebellion and

faced the fire of British musketry in a mad attempt to carry out his

hostility to the government that then was- -from that moment the

governor placed himself with his hands tied in the power of his new

advisers." Another leading Conservative paper did not scruple to say

that the composition of the present cabinet is the germ of colonial

separation from the mother country."

One can understand how

great must have been the difficulties of Bagot's situation. It was not

possible for him merely to fold his hands and to announce himself, with

general approval, as the long-desired constitutional governor. If he

attempted to actually govern, the Reformers would be up in arms; if he

left the government to his ministers, he must face tin: outcry of the

Tory faction. The ideal of one party was the abomination of the other.

The French press was of course loud in its praise of the new policy.

"To-day," said Iinerve, in speaking of the formation of the ministry, "

commences a new era, and one which will be signalized by the

administration of equal justice towards all our fellow-citizens and the

return of popular confidence in the government." "The great principle of

responsibility," said the same journal, "is thus formally and solemnly

recognized by the representative of the Crown, and sealed with the

approbation of the assembly. From this epoch dates a revolution,

effected without blood or slaughter, but none the less glorious." But

the more the French press praised Bagot's action, the more did the "

loyal" newspapers denounce it, subjecting the governor to personal

criticism and abuse entirely out of keeping with the system he laboured

to introduce. "To hear the stupid Aurore and the venomous Minerve

lauding a British governor," declared the Toronto Patriot, "is surely

proof plain that he is not what he might be; that he is a changed man

and not worthy of the cordial sympathy of the Conservative and loyal

press of Canada." It is small wonder that Bagot's health began to suffer

severely from the anxiety and distress of mind occasioned by these

malignant attacks upon his character.

A proper appreciation

of the state of public feeling evidenced by such extracts renders clear

the great significance of the LaFontaine-Baldwin alliance in the history

of Canada. Its importance is of a double character. It afforded, in the

first place, an object lesson in the principle of responsible

government; for it showed in actual operation a group of ministers

united in policy, backed by an overwhelming majority in the popular

branch of the legislature, and receiving the constitutional approval of

the governor, of whom they were the advisers. Henceforth responsible

government, the "one idea" of Robert Baldwin, was no longer merely an

"idea"; it was a known and tried system whose actual operation had

proved its possibility. Its trial, indeed, in the present case was but

brief, yet brief as it was, it remained as an ensample for future

effort. But the new government had a furt her significance. It indicated

the only possible policy by which the racial problem in the political

life of Canada could find an adequate solution. To the old-time Tory the

absorption, suppression, or at any rate the subordination of French

Canada seemed the natural, one might; say the truly British and loyal,

method of governing the united country. From now on a new path of

national development is indicated in the alliance and cooperation of the

two races, each contributing its distinctive share to the political life

of the country, and each finding in the other a healthful stimulus and

support. This is the principle, entirely contrary to the doctrines of

the older school, first introduced by the alliance of Baldwin and

LaFontame, which has since governed the destinies of Canada. On the

validity of this principle the future of the country has been staked.

If we pass from the

general consideration of the ministry before us to the legislative

history of its first session, there is but little to record. The session

was but of a month's duration (September 8th to October 12th. 1842), the

new ministers during the first part of it were still seeking reelection,

and time was lacking for a wide programme of reform. Such measures as

were carried, however, indicated clearly the policy which it proposed to

follow: to conciliate the people of French Canada by removing some of

the more burdensome restrictions imposed by the special council and to

make at least a beginning of a programme of reform, was the cardinal aim

of the government. The first law placed upon the statute-book for the

session—the law in regard to elections —evinced this latter purpose. The

elections of the day were notoriously corrupt, Fraud and violence had

been the rule rather than the exception. Under the existing system there

was but a single polling place for each constituency, an arrangement

which favoured riotous proceedings and the assemblage of tumultuous

crowds. The new election law1 provided that there should be a separate

polling place in each township or ward of every constituency, and that

each elector should vote at the polling place of the district where his

property was situated. Electors might be put on oath as to whether they

had already voted. The polls were to stay open only two days. An oath in

denial of bribery could be imposed on any voter, if it were demanded by

two electors. Firearms and other weapons might be confiscated by the

returning officer, under penalty, in case of resistance, of fine and

imprisonment. Under similar penalties it was forbidden to make use of

ensigns, standards or flags, "as party flags," to distinguish the

supporters of a particular candidate, either on election day or for a

fortnight before or after; a similar prohibition was laid down against

"ribbons," "labels" and "favours" used as party badges. These last

clauses offered an easy mark for the raillery of the Conservative press,

and offered a favourable opportunity for wilful misinterpretation by

pressing into service the never-tailing Union Jack and British loyalty.

The Patriot of Toronto speaks as follows of the tyranny of the election

law:—

"This law also

prohibits, under penalties of fines of fifty pounds, and imprisonment

for six months, or both, the exhibiting of any ensign, standard, colour,

flag, ribbon, label or favour, whatever, or for any reason whatsoever,

at any election or on any election day. or within a fortnight before or

after such a day!!! So that any body of honest electors who for a

fortnight before or after an election (being a period of one month),

shall dare to hoist the Union Jack of Old England, or wear a green or

blue ribbon m the button-hole, shall be fined fifty pounds or irnprisont*!

six months, or both, under Mr. Baldwin's election bill. We defy the

whole world to match this bill for grinding and insupportable tyranny.

Verily, Messrs. LaFontaine and Baldwin, ye use your victory over the poo>\

loyal serfs of Canada with most honourable moderation! How long this

Algerme Act will be allowed to pollute our statute-book remains yet to

be seen."

Another statute2 of the

session undertook to remedy the injustice done by Lord Sydenham towards

the city constituencies of Montreal and Quebec. He had used the power

conferred upon ham under the Act of Union3 to reconstruct these

constituencies by separating the cities from the suburbs1; under the

present statute the "ancient boundaries and limits " of the cities were

restored. A further reversal of Lord Sydenham's policy was seen in the

repeal* of a series of ordinances by which the special council had

undertaken to alter the system of law courts in Lower Canada. Sydenham's

Act in reference to winter roads in Lower Canada, a needlessly officious

piece of legislation, was also partially repealed.1 A special duty of

three shillings a quarter was imposed upon wheat from the United States;

a loan of one million, five hundred thousand pounds sterling was

authorized, and the sum of eighty-three thousand, three hundred and six

pounds was voted for the civil list. A resolution was, moreover, passed

by a large majority of the assembly (forty against twenty) declaring

that Kingston was not suitable to be the scat of government. The session

came to an end on October 12th, 1842. A useful beginning had been made

but no legislation of a sweeping character had been passed. The

adversaries of the government did not hesitate to taunt the ministry

with having promised much and done little. "After all the rumpus about

responsible government," said the Woodstock Herald, " the session is

over, and we are all just as we were— waiting for something, we scarcely

know what. But we all know that the parliament has shown itself nothing

but a debating club."

At the time of their

first ministry both LaFontaine and Baldwin may be said to have been

entering upon the prime of life. Baldwin was thirty-eight years old,

LaFontame only thirty-four. In personal appearance they presented in

many ways a contrast. LaFontaine was a man of striking presence, of more

than ordinary stature, and robust and powerful frame. His massive brow

and regular features, the thoughtful east of his countenance and the

firm fines of the mouth, offered an almost exact resemblance to the face

of the Emperor Napoleon. On his visiting the Invalides in Paris,

LaFontaine was surrounded by the veterans of Napoleon's guard, who are

said to have thrilled with emotion at seeing among them the walking

image of their dead emperor. When Lady Mary Bagot, who remembered the

emperor, saw LaFontaine for the first time she could not repress an

exclamation of astonishment, "I was not certain that he is dead," she

cried, "I should say it was Napoleon." The habitual gravity of

LaFontaine's manner and the dignity of his address enhanced still

further the impression of power conveyed by his firm features and steady

eye. His colleague was a man of different type and less striking in

general appearance. In stature Baldwin stood rather above the average,

being about five feet ten inches in height, though his heavy frame and

the slight stoop of his broad shoulders prevented him from appearing a

tall man. His eyes were grey and his hair of a dark brown, as yet

untinged with grey. The features were lacking n mobility7 and the

habitual expression of his face was that of serious thought, but the

extreme kindliness of his heart and the truthfulness of his whole being,

coupled with a manner that was unassuming and free from conceit, lent to

his address a suggestion of rugged honesty and force and extreme 148

gentleness, that won him the unfailing affection of those about him.

As the autumn

progressed, disquieting rumours began to prevail in regard to the state

of the governor-generals health. It is a strange thing that thrice

running the destinies of Canada should have been profoundly affected by

the premature death of those sent out to administer its government.

"Canada has been too much for him," John Stuart Mill had said of Lord

Durham. With equal truth might it be said that Canada had proved too

much for Sir Charles Bagot. The governor had come to the country in

excellent health. The firm and vigorous tone in which he had read his

first and only speech from the throne had been the subject of general

remark, and had seemed to indicate that Bagot was destined for a

vigorous old age. But the cares of office weighed heavily upon him. He

had not anticipated that his policy of good-will and conciliation would

have exposed him to the bitter attacks of the discomfited Tories; still

less had he expected that his conduct, as appears to have been the case,

would have been an object of censure at the hands of the home

government. It is undoubted that the symptoms of heart trouble and

general decline which now began to appear were aggravated by the

governor's sense of the failure of his mission as peacemaker, and by the

distress caused by the crude brutality of his critics.

The autumn months of

1842 must indeed have been full of bitterness to Bagot. The opposition

to his administration had assumed a personal note, for which the

rectitude of his intentions gave no warrant. Organizations called

Constitutional Societies, :n remembrance of Tory loyalty before the

rebellion, had sprung nto new life. The parent society at Toronto was

reproduced in organizations in the country districts. The "anti-British

policy of Sir Charles Bagot" was denounced in the plainest terms. His

ministry was openly branded as a ministry of traitors and rebels. The

influence of Edward Gibbon Wakefield and other private advisers was made

a salient point of attack, and the governor was represented as

surrounded by a group of counsellors—"the Hinckses, the Wake-fields and

the Girouards, remarkable for nothing but bitter hatred to monarchical

and loyal institutions." The press of the mother country joined in the

outcry. The Times undertook to demonstrate the folly of admitting to the

ministry a man like LaFontaine, "who," it asserted, "had had a price set

upon his head." The Morning Her aid'2 went still further; it declared

the whole system of representative institutions m Lower Canada a

mistake. That province, it said, needed "despotic government, strong,

hist and good- administered by a governor-general responsible to

parliament." " If Sir Charles Bagot be right," it argued, "then Lord

Gosford and Sir Francis Head must have been wrong," which evidently was

absurd.

In how far the British

government itself joined in these censorious attacks cannot accurately

be told, but Bagot had certainly received from Lord Stanley, the

colonial secretary, letters condemning the policy he had seen fit to

adopt. The Duke of Wellington had denounced the acceptance of the new

Canadian ministry by the governor as surrendering to a party still

affected with treason. "The Duke of Wellington," wrote Sir Robert Peel,

" has been thunderstruck by the news from Canada. He considers what has

happened as likely to be fatal to the connection with England. . .

Yesterday he read to me all the despatches, and commented on them most

unreservedly. He perpetually said, 'What a fool the man [Bagot] must

have been, to act as he has done 1 and what stuff and nonsense he has

written ! and what a bother he makes about his policy and his measures,

when there are 110 measures but rolling himself and his country in the

mire!'" Even Peel himself felt by no means easy about the situation, nor

did he accept the absolute validity of the constitutional principle as

applied to Canadian government. " I would not," he wrote to Stanley,

"voluntarily throw myself into the hands of the French party through

fear of being in a minority. ... I would not allow the French party to

dictate the appointment of men tainted by charges, or vehement

suspicion, of sedition or disaffection to British authority, to be

ministers."

As the winter drew on

it was evident that Sir Charles could no longer adequately fulfil his

duties. He was obliged to postpone the meeting of the parliament which

was to have taken place in November. His physicians urgently recommended

that he should relinquish his office, and the oncoming of a winter of

unwonted severity still further taxed his fading strength. He forwarded

to the borne government a request for his recall. In view of his

enfeebled condition-, the government was able to grant his prayer

without seeming to reflect upon the character of his administration. But

Bagot was not dest ined to see England again. Though released from

office 011 March 30th, 1843, the day on which he yielded place to Sir

Charles Metcalfe, he was no longer in a condition to undertake the

homeward voyage, and was compelled to remain at Alw ington House, in

Kingston. Six weeks later, (May 19th. 1843), his illness terminated in

death. Before going out of office he had uttered a wish to his assembled

ministers that they would be mindful to defend his memory. The prayer

was not unnecessary, for the bitter 1nvective of his foes was not hushed

even in the presence of death.

"Even when Sir Charles

Bagot breathed his last," says a chronicler of the time, himself a Tory

and a disappointed place-hunter, " such was the exasperation of the

public mind, that they (sic) scarcely accorded to him the common

sentiments of regret which the departure of a human being from among his

fellow-men occasions. . . . The Toronto Patriot in particular, the

deadly and uncompromising enemy of the administration of the day,

hesitated not to proclaim that the head of the government was an

imbecile and a slave, while other journals, even less guarded in their

language, boldly pronounced a wish that his death might free the country

from the state of thraldom into which it was reduced."1 Every good cause

has its martyrs. The governor-general had played his part honestly and

without self-interest, and when the list of those is written who have

upbuilt the fabric of British colonial government, the name of Bagot

should find an honoured place among their number. |