|

ON March 29th. 1843,

the little town of Kingston was once more astir with expectancy and

interest over the arrival of a new governor-general. Sir Charles

Metcalfe had sailed from Liverpool to Boston, and thence had journeyed

overland to Kingston, the country being in that inclement season "one

mass of snow." His journey terminated ,ii a drive across the frozen lake

and river, and a state entry, with no little pageantry, into his

colonial capital. "He came," said a Kingston correspondent of the time,

" from the American side, in a close-bodied sleigh drawn by four greys.

He was received on arriving at the foot of Arthur Street by an immense

concourse of people. The male population of the place turned out on

masse to greet Sir Charles, which they did with great enthusiasm. The

various branches of the fire department, the Mechanics' Institution and

the national societies, turned out with their banners, which, with many

sleighs decorated with flags, made quite a show. Sir Charles Metcalfe is

a thorough-looking Englishman, with a jolly visage."

In the drama of

responsible government in Canada, it was the unfortunate lot of this

"thorough-looking Englishman with a jolly visage," to be east for the

part of villain. His attempt to strangle the infant Hercules in its

cradle, to reassert the claim of the governor to the actual control of

the administration, forms the most important and critical episode of the

story before us and merits a treatment in some detail. Such a treatment

may, perhaps, be best introduced by a discussion of the personality and

personal opinions of the new governor, and in particular of his opinions

on the vexed question of colonial administration. The word "villain "

that has just been used, must be understood in a highly figurative

sense. Metcalfe was a man of many admirers. Gibbon Wakefield has

pronounced him a statesman f whom God made greater than the colonial

office." Macaulay indicates for him a perhaps even higher range of

distinction in calling him, "the ablest civil servant I ever knew in

India." His enthusiastic biographer2 tells us that on his retiring from

his administration of Jamaica, the "coloured population kneeled to bless

him," while " all classes of society and all sects of Christians

sorrowed for his departure, and the Jews set an example of Christian

love by praying for him :n their synagogues." In face of such a record

it seems almost a pity that Sir Charles should have abandoned the

coloured populations of Jamaica and Hyderabad to assume the care of the

un coloured people of Canada. That Metcalfe was an upright, honourable

man, disinterested in his motives and conscientious in the performance

of what lie took to be his duty, is hardly open to doubt. But it may

well be doubted whether the antecedent training that he had received had

not unfitted, rather than fitted, him for the position he was now called

upon to assume.

In the British system a

great gulf is fixed between the administration of a dependency and the

governorship of a self-governing colony. Of the greatness of this gulf

Metcalfe appears to have had no proper appreciation, and he was, in

consequence, unable to rid his mind of the supposed parallel between the

different parts of the empire in which he had been called upon to act as

governor. In a letter which he addressed to Colonel Stokes, one of his

Indian correspondents, during his troubles in Canada, he undertakes to

make his difficulties with the Canadian legislature apparent by the

following interesting analogy: "Fancy such a state of things in India,

with a Mohammedan council and a Mohammedan assembly, and you will have

some notion of my position." In view of the very limited number of

Mohammedans in the Canadian assembly, it is to be presumed that the

notion thus communicated would be a somewhat artificial one.

Sir Charles Metcalfe,

at the time of his coming to Canada, was fifty-eight years old.1 For

some time previous he had been suffering from a dangerous and painful

malady—a cancerous growth in the left cheek—which had occasioned his

retirement from his previous position. An operation performed in England

had seemed to remove all danger of a fatal termination of the disorder,

and Sir Charles, in coming to Canada, hoped that he had at last

recovered from his long affliction.

What may seem strange

in connection with Metcalfe's regime in Canada, and his attitude towards

Canadian political parties, was that he was not, as far as British

politics were concerned, a Tory or a friend of the royal prerogative. He

was, on the contrary, to use the words of his biographer, " a Whig and

something more than a Whig." The same authority3 has further described

him as " a statesman known to be saturated through and through with

liberal opinions." Metcalfe himself, in a letter written shortly before

his appointment, spoke of his own opinions and his political position in

the following terms: "In the present predominance of Toryism among the

constituencies, there is no chance for a man who is for the abolition of

the Corn Laws, vote by ballot, extension of the suffrage, amelioration

of the Poor Laws for the benefit of the poor, equal rights to all sects

of Christians n matters of religion, and equal rights to all men in

civil matters."'

On the strength of such

a declaration -t might have been supposed that Metcalfe would have

gravitated naturally towards the Reform party of Canada, at the basis of

whose programme civil and religious equality and the doctrine of equal

rights lay as a corner-stone. But the lamp of Metcalfe's Liberalism

burned dun in the colonial atmosphere. His inclinations were all on the

side of the Tory party, whose fen id and ostentatious loyalty offered a

cheering contrast to the stiff-necked independence of the Reformers. "It

is," he said, "the only party with which I can sympathize. I have no

sympathy with the anti-British rancour of the French party or the

selfish indifference towards our country of the Republican party. Yet

these are the parties with which I have to cooperate." The expression,

"Republican party," shows that the incessant accusation of disloyalty

brought by the Conservative journalists against their opponents, was not

without its effect upon the governor's mind. By sheer force of iteration

the Conservatives had convinced themselves that they were the one and

only section of the people truly loyal to the Crown ; and since the

governor was the immediate and visible representative of the Crown in

Canada, there was a natural temptation to construe his attitude into a

declaration of personal allegiance.

But although Metcalfe

might plead guilty to a spontaneous sympathy with the Tory party, he had

no intention of identifying or allying himself with any of the rival

factions. On the contrary-, he cherished, as had his predecessors, the

belief that his proper attitude and vocation should be that of the

peacemaker, the wise administrator enabled by the altitude of his office

to compose the differences that severed his fractious subordinates. "I

dislike extremely," he said, "the notion of governing as a supporter of

any particular party. I wish to make the patronage of the government

conducive to the conciliation of all parties by bringing into the public

service the men of greatest merit and efficiency, without any party

distinction."

The governor seems,

however, to have recognized that he could not disregard the fact that

the party at present in power had the support of the assembly behind

them. "Fettered as I am," he wrote, " by the necessity of acting with a

council brought into place by a coalition of parties, and at present n

possession of a decided majority in the representative assembly, I must

in some degree forego my own inclinations in those respects." It was his

intention, he told the colonial secretary, to treat the executive

council with the confidence and cordiality due to the station which they

occupied, but he; was prepared to be on his guard against any

encroachments. This last phrase touches the root of the matter. Of what

nature were the "encroachments" which Metcalfe was determined not to

permit ? How did he interpret his own position in reference to the

executive officers that were his constitutional advisers? What, in other

words, was his opinion on the application of responsible government ?

The answer to this question can best be found by an examination of

Metcalfe's own statements as they appear in his confidential

correspondence with the colonial office.

"Lord Durham's

meaning," he wrote, "seems to have been that the governor should conduct

his administration in accordance with public feeling, represented by the

popular branch of the legislature, and it is obvious that without such

concordance the government could not be successfully administered. There

is no evidence in what manner Lord Durham would have carried out the

system which he advocated, as it was not brought into effect during his

administration. Lord Sydenham arranged the details by which the

principle was carried into execution. In forming the executive council

he made it a rule that the individuals composing it should be members of

the popular branch of the legislature, to which, I believe, there was

only one exception: the gentleman app<tinted to be president being a

member of the legislative council. Lord Sydenham had apparently no

intention of surrendering the government into the hands of the executive

council. On the contrary, he ruled the council, and exercised great

personal influence in the election of members to the representative

assembly. ... I am not aware that any great change took place during

that period of the administration of Sir Charles Bagot which preceded

the meeting of the legislature, but this event was instantly followed by

a full development of the consequences of making the officers of the

government virtually dependent for the possession of their places on the

pleasure of the representative body. The two extreme parties in Upper

Canada most violently opposed to one another, coalesced solely for the

purpose of turning out the office-holders, or, as it is now termed, the

ministry of that day, with no other bond of union, and with a mutual

understanding that having accomplished that purpose, they would take the

chance of the consequences, and should be at liberty to follow their

respective courses. The French party also took part ia this coalition,

and from its compactness and internal union, formed its greatest

strength. These parties together accomplished their joint purpose. They

had expected to do so by a vote of the assembly, but hi that were

anticipated by the governor-general, who in apprehension of t he

threatened vote of want of confidence m members of his council, opened

negotiations with the leaders of the French party, and that negotiation

terminated in the resignation or removal from the council of those

members who belonged to what is called by themselves the Conservative

party, and in the introduction of five members of the united French and

Reform parties. . . . These events were regarded by all parties in the

country as establishing in full force the system of responsible

government of which the practical execution had before been incomplete.

From that time the tone of the members of the council and the tone of

the public voice regarding responsible government has been greatly

exalted. The council are now spoken of by themselves and others

generally as the 'ministers,' the 'administration,' the 'cabinet,' the

'government,' and so forth. Their pretensions are according to this new

nomenclature. They regard themselves as a responsible ministry, and

expect that the policy and conduct of the governor shall be subservient

to their views and party policy."

Very similar in tone is

a despatch of May 12th, 1843, in which the governor declared that none

of his predecessors had really been face to face with the problem of

granting or withholding self-government. "Lord Durham," he said, " had

no difficulty in writing at leisure in praise of responsible government.

. . Lord Sydenham put the idea in force without suffering himself to be

much restrained by it. . . Sir Charles Bagot yielded to the coercive

effect of Lord Sydenham's arrangements. Now comes the tug of war, and

supposing absolute submission to be out of t he question. I cannot say

that I see the end of the struggle if the parties alluded to really mean

to maintain it." The part that the new governor intended to play in this

impending tug of war is clearly indicated in this communication to Lord

Stanley, He had no intention of adapting himself to the position of a

merely nominal head of the government, controlled by the advice of his

ministers.

"I am required," he

wrote, "to give myself up entirely to the council; to submit absolutely

to their dictation; to have no judgment of my own; to bestow the

patronage of the government exclusively on their partisans; to proscribe

their opponents; and to make some public and unequivocal declaration of

my adhesion to these conditions- including the complete nullification of

Her Majesty's government—a course which he [Mr. LaFontaine, under

self-deception, denominates Sir Charles Bagot's policy, although it is

very certain that Sir Charles Bagot meant no such thing. Failing of

submission to these stipulations, I am threatened with the resignation

of Mr. LaFontaine for one, and both he and I are fully aware of the

serious consequences likely to follow the execution of that menace, from

the blindness with which the French-Canadian party follow their leader.

. . . The sole question is, to describe it without disguise, whether the

governor shall be wholly and completely a tool 164 in the hands of the

council, or whether he shall have any exercise of his own judgment in

the administration of the government. Such a question has not come

forward as a matter of discussion, hut there is no doubt the leader of

the French party speaks the sentiments of others of his council beside

himself. . . . As I cannot possibly adopt them, I must be prepared for

the consequences of a rupture with the council, or at least the most

influential portion of it. It would be very imprudent on my part to

hasten such an event, or to allow it to take place under present

circumstances, if it can be avoided—but I must expect it, for I cannot

consent to be the tool of a party. . . . Government by a majority is the

explanation of responsible government given by the leader in this

movement, and government without a majority must be admitted to be

ultimately impracticable. But the present question, the one which is

coming on for trial in my administration, is not whether the governor

shall so conduct his government as tc meet the wants and wishes of the

people, and obtain their suffrages by promoting their welfare and

happiness—nor whether he shall be responsible for his measures to the

people, through their representatives—but he shall, or shall not, have a

voice m his own council. . . . The tendency and object of this movement

is to throw off the government of the mother country in internal affairs

entirely —but to be maintained and supported at her expense, and to have

all the advantages of connection, as long as if may suit the majority of

the people of Canada to endure it. This is a very intelligible and very

convenient policy for a Canadian riming at independence, but the part

that the representative of the mother country is required to perform in

it is by no means fascinating."

The tenor of Sir

Charles Metcalfe's correspondence cited above, which belongs to the

period between his assumption of the government and the meeting of the

parliament, shows that the difficulties which were presently to

culminate in the "Metcalfe Crisis" were already appearing on the

horizon. Meantime the new governor was made the recipient of flattering

addresses from all parts of the country and from citizens of all shades

of opinion. The difficulties of Metcalfe's position can be better

understood when one considers the varied nature of these addresses and

the conflicting sentiments expressed. Some were sent up from Reform

constituencies whose citizens expressed the wish that he might continue

to tread in the path marked out by his predecessor. Others were from

"loyal and constitutional societies" whose prayer it was that he might

resist the designing encroachments of his anti-British advisers. The

people of the townsl ip of Pelham, for example, declared that they " had

learned with unfeigned sorrow that unusual efforts had been made to

weaken His Excellency's opinion of Messrs. Baldwin and LaFontaine and

the other ] 66 members of his cabinet." The Constitutional Society of

Orillia begged to " state their decided disapproval of the policy

pursued by our late governor-general." "We have not the slightest wish,"

they said, "to dictate to your Excellency, but, conscientiously

believing that i t would tend to the real good, happiness, and

prosperity of the country, we in all humility venture to recommend the

dismissal of the following members from your councils: The Hon. Messrs.

Harrison, LaFontaine, Baldwin, Hincks and Small." Iu some eases1 rival

addresses, breathing entirely opposed sentiments were sent up from the

same place. It is small wonder that Metcalfe became deeply impressed by

the bitterness of party faction existing in Canada.

"The violence of party

spirit," he wrote to Lord Stanley, "forces itself on one's notice

immediately on arrival in the colony; and threatens to be the source of

all the difficulties which are likely to impede the successful

administration of the government for the welfare and happiness of the

country." In this statement may be found the basis for such defense as

can be made for Metcalfe's conduct in Canada. He was honestly convinced

that the antipathy between the rival factions was assuming dangerous

proportions, and that it threatened to culminate in a renewal of civil

strife. In this position of affairs it seemed to him Ills evident duty

to alleviate the situation by using sueh influence and power as he

considered to be lawfully entrusted to him, to counteract the intensity

of the party struggle. In particular it seemed to him that his right of

making appointments to government offices ought to be exercised with a

view to general harmony, and not at the dictates and in the interests of

any special political group. "I wish," he wrote, "to make the patronage

of the government conducive to the conciliation of all parties, by

bringing into the public; service the men of greatest merit and

efficiency, without any party distinction."

This sentiment is 110

doubt, as a sentiment, very admirable. But what Metcalfe did not realize

was that it was equivalent to saying that he intended to distribute the

patronage of the government as he thought advisable, and not as the

ministry, representing the voice of a majority of the people, might

think advisable. Metcalfe seems to have been aware from the outset that

his views on this matter would not be readily endorsed by his ministers.

He spoke of the question of the patronage as "the point on which he most

proximately expected to incur a difference with them." Indeed it may be

asserted that Metcalfe was convinced that he must, sooner or later, come

to open antagonism with his cabinet. As early as June, 1843, he wrote to

Stanley: " Although I see no reason now to apprehend an immediate

rupture, I am sensible that it may happen at any time. If all [of the

ministers] were of the same mind with three or four t would be more

certain. But there are moderate men among them, and they are not all

united in the same unwarrantable expectations."

It is not difficult to

infer from what has gone before that Metcalfe had but little personal

sympathy with the two leaders of his cabinet. In his published

correspondence we have no direct personal estimate of LaFontaine and

Baldwin. But the account given by his "official" biographer of the two

Canadian statesmen undoubtedly reflects opinion gathered from the

governor-general's correspondence, and is of interest in the present

connection. "The two foremost men in the council," writes Kaye, "[were]

Mr. LaFontaine and Mr. Baldwin, the attorneys-general for Lower and

Upper Canada. The former was a French-Canadian and the leader of his

party in the colonial legislature. . . . All his better qualities were

natural to him; his worse were the growth of circumstances. Cradled, as

he and his people had been, in wrong, smarting for long years under the

oppressive exclusiveness of the dominant race, he had become mistrustful

and suspicious; and the doubts which were continually floating in his

mind had naturally engendered there indecision and infirmity of

purpose." How little real justification there was for this last

expression of opinion may be gathered from the comments thereupon

published by Francis Hincks in later years. "I can hardly believe that

there is a single individual n the ranks of either party," he says "who

would admit, that Kaye was correct in attributing to [Sir] Louis

LaFontaine ' indecision and infirmity of purpose.' I can declare for my

own part that I never met a man less open to such an imputation."

Metcalfe's biographer saw fit, however, to qualify his strictures of

LaFontaine by staling that he was a "just and honourable man" and that

"his motives were above suspicion."

A still less flattering

portrait is drawn by the same author when he goes on to speak of Robert

Baldwin. "Baldwin's father," says Kaye, "had quarrelled with his party.

and, with the characteristic bitterness of a renegade, had brought up

his son m extremest hatred of his old associates, and had justified into

him the most liberal (sicJ opinions. Robert Baldwin was an apt pupil;

and there was much in the circumstances by which he was surrounded.—in

the atrocious misgovernment of his country . . . —to rivet him in the

extreme opinions he had imbibed in his youth. So he grew up to be ail

enthusiast, almost a fanatic. He was thoroughly in earnest; thoroughly

conscientious; but he was to the last degree uncompromising and

intolerant. He seemed to delight in strife. The might of mildness he

laughed to scorn. It was said of him that he was not satisfied with a

victory unless it was gained by violence—that concessions were valueless

to him unless he wrenched them with a strong hand from his opponent. Of

an unbounded arrogance and self-conceit, he made no allowances for

others, and sought none for himself. There was a sort of sublime egotism

about him—a magnificent self-esteem, which caused him to look upon

himself as a patriot, whilst he was serving his own ends by the

promotion of his ambition, the gratification of his vanity or spite. His

strong passions and his uncompromising spirit made him a mischievous

party leader and a dangerous opponent. His influence was very great. He

was not a mean man : he was above corruption : and there were many who

accepted his estimate of himself and believed him to be the only pure

patriot in the country. During the illness of Sir Charles Bagot he had

usurped the government . The activity of Sir Charles Metcalfe, who did

everything for himself and exerted himself to keep every one in his

proper place, was extremely distasteful to him." It is an old saying

that there is no witness whose testimony is so valid as that of an

unwilling witness : and it is possible to read between the lines of this

biased estimate a truer picture of the man. " In this dark photograph,"

says the author of The Irishman in Canada} "the impartial eye recognizes

the statesman, the patriot, the great party leader, who was not to be

turned away by fear or favour from the work before him,"

As early as May, 1843,

an important episode took place in reference to the question of

appointments, a question destined later to be the cause of the

resignation of the ministry. The matter is of special historical

significance in that LaFontaine sawr fit to draw up a memorandum

explaining what had occurred and putting definitely on record the

attitude assumed by himself and his colleagues in their interpretation

of their relation to the governor-general. The facts in question were as

follows. The office of provincial aide-de-camp for Lower Canada had

fallen vacant. The post was a sinecure, the salary for which was voted

yearly by the assembly. A certain Colonel De Salsberry, a son of the De

Salsberry of Chateauguay, came to Kingston to solicit the office. He had

an interview with Sir Charles Metcalfe, as a result of which it was

reported that he had received the promise of the appointment. The

private secretary of the governor--general, a certain Captain Higginson,

met LaFontaine at a dinner given by His Excellency in Kingston.

Higginson discussed the vacant office with LaFontaine and was informed

that, if the post were given to Colonel De Salsberry, the appointment

would be viewed with disfavour by the people of Lower Canada. On this

Iligginson asked the attorney-general if lie might, at his convenience,

have an opportunity of discussing with him the present political

situation. LaFontaine granted this request and Higginson called upon

hiin at his office next day. A conversation of some three hours duration

ensued in which the question of the nature and meaning of responsible

government was discussed at full length. Captain Iligginson declared

that he was acting in the matter in a purely personal character and not

as the accredited agent of the governor-general. This was probably true

in the technical and formal sense, but it cannot be doubted that

Higginson was expressing the known sentiments of Sir Charles Metcalfe;,

and that he duly reported the conversation to the governor, whose

subsequent actions were evidently influenced thereby. The substance of

the argument may best be given in the words of La Fontaine's published

memorandum. opinions which had been so often expressed on this subject

as well in the House as elsewhere. He explained to him that the

councillors were responsible for all the acts of the government with

regard to local matters, that they were so held by members of the

legislature, that they could only retain office so long as they

possessed the confidence of the representatives of the people, and that

whenever this confidence should be withdrawn from them they would retire

from the administration; that these were the principles recognized by

the resolutions of September 3rd, 1811, and that it was on the faith of

these principles being carried out that he had accepted office. The

question of consultation and non-consultation was brought 011 the tapis

with reference to the exercise of patronage, that is to say, the

distribution of places at the disposal of the government. The councillor

informed Captain Higginson that the responsibility of the members of the

administration, extending to all the acts of the government in local

matters, comprehending therein the appointment to offices, consultation

in all those cases became necessary, it being afterwards left to the

governor to adopt, or reject the advice of his councillors; His

Excellency not being bound, and it not being possible to bind him. to

follow that advice, but, on the contrary, having a right to reject it:

but in this latter case, if the members of council did not choose to

assume the responsibility of the act that the governor wished to

perform, contrary to their advice, they had the means of relieving

themselves from it. by exercising their power of resigning." As Captain

Higginson appears to have demurred to this interpretation of the meaning

of the September resolutions, LaFontaine asked him to state the

construction which he himself put upon them. Higginson replied.—and in

replying may properly be considered to have expressed the sentiments of

Sir Charles Metcalfe,—that although the governor ought to choose his

councillors from among those supposed to have the confidence of the

people," nevertheless "each member of the administration ought to be

responsible only for the acts of his own department, and consequently

that he ought to have the liberty of voting with or against his

colleagues whenever he judged fit; that by this means an administration

composed of the principal members of each party might exist

advantageously for all parties, and would furnish the governor the means

of better understanding the views and opinions of each party, and would

not fail, under the auspices of the governor, to lead to the

reconciliation of all." From these views La-Fonta-ne expressed an

emphatic and unqualified dissent. "If," he said, " the opinions [thus]

expressed upon the sense of the resolutions of 1841 were those of the

governor-general, and if His Excellency was determined to make them the

rule for conducting his government, the sooner he made it known to the

members of the council the better, in order to avoid all

misunderstanding between them." LaFontaine added that in such a case he

himself would feel it his duty to tender his resignation. Since there is

undeniable evidence that Higginson related this conversation in full to

Sir Charles Metcalfe, it is plain that henceforth the latter was quite

aware of the point of view taken by his cabinet, and must have felt that

a persistence in the course he contemplated could not but lead to an

open rupture. Indeed it appears to have been very shortly after tins

incident that he wrote to Lord Stanley that his " attempts to conciliate

all parties are criminal in the eyes of the council, or at least of the

most formidable member of it."'

As yet, however, the

difficulties that were im pending between the governor and his ministers

were unknown to the country at large. The "want of cordiality and

confidence " between Metcalfe and his advisers had indeed become " a

matter of public rumour," but His Excellency had been careful >n his

answers to the addresses praying for the removal of the ministry to

rebuke the spirit of partisan bitterness in which they were couched. The

governor was consequently able to summon parliament in the autumn of

1843 with a fair outward show of harmony, and it was not until near the

close of the year that the smouldering quarrel broke into a flame.

Meantime the parliament had passed through a session of great activity

and interest, and had undertaken a range of legislation which rapidly

developed the extent and meaning of the Reform programme. In this, the

third session of the first parliament, which lasted from September 28th

until December 9tli (1843), the ministry enjoyed in the assembly an

overwhelming support. Of the eighty-four members of the House, some

sixty figured as the supporters of the government; and even in the

legislative council, the appointment of Dr. Baldwin, the father of the

attorney-general, AEnnlius Irving and others, lent support to the

government. Mr. Draper, on the other hand, now elevated to a seat in the

legislative council, embarked on a determined and persistent opposition

to the measures of the administration. Six new members had been elected

during the recess to fill vacancies m the assembly. Prominent among

these was Edward Gibbon Wakefield, elected for Beauhamois, notable

presently as one of the defenders of Sir Charles Metcalfe. Wakefield had

already attained a certain notoriety in England for his views on the ft

art, of colonization," and for the theories of land settlement which he

bad endeavoured to put into practice in Austral; i and New Zealand.1 He

had already spent some time in Canada with Lord Durham u an unofficial

capacity, and had had some share in the preparation of the report. He

had returned to Canada n 1841. and as has been already noted, had been

on intimate terms with Bagot and his ministry. He was anxious, according

to Hincks, to press a certain land scheme of his invention on the

government, and it was their refusal to meet his views which led him

presently to oppose heir policy and to become the confidential adviser

and the apologist of Sir Charles Metcalfe.

Hopelessly outvoted as

they were in the Lower House, the Tories and other opponents of the

government nevertheless maintained a spirited opposition. Sir Allan

MacNab and his adherents persisted at every available opportunity in

raising the racial question, in reviving uncomfortable recollections of

1837, and in assuming a tone of direct personal attack, the impotence of

which against the solid majority of the government lent it an added

venom.1 The government in its turn was well represented in debate.

Baldwin, LaFontaine and Hincks were all members of the assembly; being

now united in policy, the combined power of their leadership and the

ardour which they put into their legislative duties, easily held their

followers together and enabled them to enjoy a continued and unwavering

support. A sort of natural division of labour had been instituted among

them. The larger measures of the Reform programme were introduced by

Baldwin: LaFontaine was especially concerned with the alterations to be

effected in the judicial system of Lower Canada and cognate matters,

while Hincks assumed the care of fiscal and commercial legislation.

A contemporary account1

of Francis Ilincks during the session of 1813, gives a vivid idea of the

legislature of the day and the prominent part played in its

deliberations by the inspector-general. "He [Mr. Hineks] had a portable

desk beside him and a heap of papers. He was as busy as a nailer,

writing, reading, marking down pages, whispering to the men on the front

seat, sending a slip of paper to this one and that one, a hint to the

member speaking; there was no mistaking that man. Presently he stood up

and started off full drive. — half a dozen voices cry out. 'Hear, hear!'

'No! No!' He picks up a slip of paper and the whole House is silent. The

figures come tumbling out like potatoes from a basket He snatches up a

journal or some other document, and having established his position he

goes ahead again. The inspector-general, Mr. Hincks, is decidedly the

man of that House. When one has observed with what attention he is

listened to by every member, when we look up to the reporters, who are,

during half the time when the other speakers are up, looking on wearily,

now all hard at their tasks, catching every word they can lay hold of,

it is not difficult to guess how it has happened that Francis Hincks has

been one of the best abused men that ever lived in Canada. No wonder the

old Compact hated him: they foresaw n him a sad enemy to vermin. He is a

real terrier. He speaks much too rapidly; and in consequence runs into a

very disagreeable sort of stammering. His manner of reading off

statistical quotations is peculiarly censurable. It is impossible for

reporters to take down the figures correctly, and the honourable

gentleman should reflect of what great importance it is to himself and

the ministry that all such matter be correctly reported."

The measures of the

session included altogether sixty-four statutes assented to by the

governor, with nine other bills reserved for the royal assent, of which

four subsequently became law. Of these, many were of an entirely

subordinate character and need no mention, but the more important

measures require some notice. Among the matters to which the attention

of the House was early directed was the question of the seat of

government. Lord Sydenham's selection of Kingston had given

dissatisfaction m both sections of the province, and many

representations had been forwarded to the home government requesting

that some other

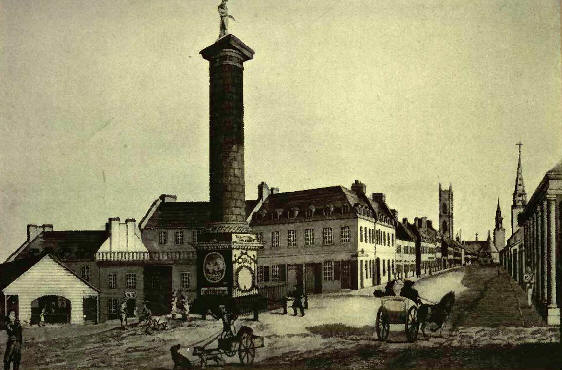

Notre Dame Street, Montreal, 1840

capital might be

selected. Montreal, Quebec and Toronto all aspired to the coveted honour.

Even Bytown, as the present city of Ottawa was then called, was favoured

by some persons, owing to its inland sit nation and its immunity from

frontier attack. But in point of wealth, importance and natural

situation, Montreal seemed obviously destined to be the capita] of

Canada. It was at this time a city of over forty thousand inhabitants.

Its position at the head of ocean navigation rendered it, as now, the

commercial emporium of the country, and the narrow streets near the

water front,—St. Paul and Notre Dame, then the principal mercantile

streets of the town,—were crowded during the season of navigation with

the rush of its seagoing commerce. The extreme beauty of the situation

of the city, its historical associations and its manifest commercial

greatness of the future, ought to have placed the superiority of its

claims beyond a question. But the racial antagonism, which was the

dominant feature of the politics of the hour, rendered the question one

of British interest as opposed to French. Montreal was indeed by no

means an entirely French city. It numbered several thousand British

inhabitants, had two daily newspapers published in English and had in it

(to quote the words of Dr. Tache in the assembly) more "real English,

more out and out John Bulls, than either Kingston or Toronto."

But the Conservatives

of Upper Canada persisted in identifying Montreal with the Lower

Canadian province. "It is not," said the New York Albion in an editorial

article,1 " a mere matter of holding parliamentary sessions in this

place or in that, that is involved; it is a matter that carries with it

the great question of English or French supremacy for the future."

Legally speaking the matter lay with the imperial government (acting

through the governor-general) but a representation3 was made to Sir

Charles Metcalfe and communicated by him to the Canadian parliament to

the effect that ft Her Majesty's government decline to come to a

determination in favour of any place as the future seat of government,

without the advice of the provincial legislature." It was, however, made

a proviso that the choice must be between Kingston and Montreal; Quebec

and Toronto "being alike too remote from the centre of the province." In

accordance with this message a resolution was introduced by Robert

Baldwin, and seconded by LaFontaine (November 2nd, 1843), advising the

Crown to remove the seat of government to Montreal, The members of the

administration (with the exception of Mr. Harrison, the member for

Kingston, who now resigned his post as provincial secretary) were

entirely in favour of the measure. Sir Charles Metcalfe himself

supported it. But the Tories persisted in regarding it as a betrayal of

Upper Canada. In the legislative council Mr. Draper had already

succeeded in passing resolutions condemning the proposed change, on the

ground that the retention of the capita) ri Upper Canada was a virtual

condition of the union of the two provinces. Sir Allan MacNab took even

higher ground: he regarded the journey to and from Kingston and the

sojourn in the British atmosphere of Upper Canada as a necessary

training for the French-Canadian deputies, whereby they might acquire,

by infection as it were, something of the spirit of the British

constitution.1

In despite of the

Conservative opposition, the resolution favouring the transfer of the

government was carried in the assembly by a vote of fifty-one to

twenty-seven (November 3rd. 1843). In the legislative council the

presence of the newly appointed members enabled the same resolution to

be adopted. An attempt was made by the Tories to refuse to consider the

question, on the ground that Mr. Draper's recent resolution had already

dealt with it. This contention was rejected by the Speaker, who insisted

that the resolution must be duly voted on; whereupon an indignant

councillor, Mr. Morris, said he "must protest in the most solemn manner

against A measure of the session, the work of LaFontaine, for which the

Reform party are entitled to great credit , was the Act for securing the

independence of the legislative assembly.1 The ami of this statute was

to consolidate the system of cabinet government by removing placemen

from the assembly, It enacted that after the end of the present

parliament a large number of office-holders should be disqualified for

election. The list included judges, officers of the courts, registrars,

customs officers, public accountants and many other minor officials. The

holders of the ministerial offices were of course outside of the scope

of the statute, which thus aimed to place the relation of the

legislature to the holding of office on the same footing as n the mother

country. The reasonableness of this measure was admitted even by

opponents of the government, but the question of its constitutionality

having been raised in the legislative council, it was reserved by the

governor for the assent of the Crown. This assent was duly granted.

The reorganization of

the judicial system of Lower Canada with a view to render the

administration of justice more easy and less expensive was carried

forward by LaFontaine n a series of five statutes. The district and

division courts that had been established under Mr. Draper's government

(September 18th, 1811) were abolished in favour of a simpler system of

circuit courts: a new court of appeal was organized and provision made

lor the summary trial of small causes.

Among the bills laid

before parliament, in whose preparation Baldwin was chiefly concerned, a

prominent place should be given to the bill for the discouragement of

secret societies. During the summer and autumn of 1843 the province of

Upper Canada had been the scene of deplorable and riotous strife between

the rival factions into which the Irish settlers of the colony were

divided. With the large immigration from the British Isles during the

preceding years, a great number of Irish had come into the country.

Unfortunately these had seen fit to carry with them into Canada the

unhappy quarrels of their native country, and nowhere was the strife of

Orangemen and Repealers, Protestants and Catholics, more ardent than in

the little Canadian capital. The events of the year 1843, during which

all Ireland was in a frenzy of excitement over O'Connell's agitation for

repeal, naturally precipitated a similar agitation in Canada. Here the

situation was further aggravated by the fact that the two parties of

Irishmen were in a sort of natural alliance with the rival political

factions of Canada. The Orangemen, with their ostentatious attachment to

the British Crown, found allies in the Tories, while their Catholic

opponents had much in common with their co-religionists of French

Canada. Orange lodges had sprung into being throughout Upper Canada:

"Hibernian societies" of Irish Catholics flaunted in defiance the

colours and insignia of their associations.

In such a state of

affairs, collisions between the rival parties were inevitable. At

Kingston, on the anniversary of the battle of the Boyne, serious

troubles occurred; several persons were wounded, and one killed; the

troops had to be called out to maintain order. On a later occasion the

streets were placarded with bills announcing rival assemblages, one in

aid of the cause of repeal, the other for preventing the repeal meeting,

"peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must." The unofficial action of the

governor and the cabinet prevented the holding of the meetings.

Sir Charles Metcalfe

was obviously alarmed at the prospect of a general conflagration.

Humours had reached him that the Irish of New York were busily engaged

at drill under French officers, and that an invasion of Canada was to be

attempted. "It is supposed," he wrote to Stanley, "that if any collision

were to occur in Ireland between the government and the disaffected, it

would be followed by the pouring of myriads of Roman Catholic Irish into

Canada from the United States." It is just possible that this

apprehension caused the governor to look more than ever towards the

Tories as an ultimate support. In the course of the month of July he had

an interview with a Mr. Gowan (then grand-master of the Grand Orange

Lodge of Canada and a man of the greatest influence), after which the

grand-master wrote a mysterious confidential letter to a friend, in

which he told his correspondent "not to be surprised if Baldwin, Hincks

and Harrison should walk." Mr. Gowan said, furthermore, that he had

given his views to the governor maturely and in writing} It is quite

possible that the grand-master had recommended a reconstruction of the

government as the price of obtaining the support of the Orange order.

Meantime, however, the tumults of the rival Irish factions continued

unabated. At Toronto, for example, during the time when legislation in

regard to secret societies was being discussed, an Orange mob gathered

in the streets one November night, having amongst them a cart with a

gibbet and effigies of Baldwin and Hincks placarded with the word

"Traitors," which effigies were burut during a scene of great confusion

before the residence of Dr. Baldwin."

It was in order to

discourage, as far as possible, the manifestations of the Irish

societies that Baldwin introduced (October 9th, 1843) his bill in regard

to secret societies. The provisions of the bill declared all societies

(with the exception of the Freemasons) to be illegal if their members

were bound together by secret oaths and signs: members of such societies

were to be incapable of holding office or of serving on juries: all

persons holding public office were to be called upon to declare that

they belonged to no such societies: innkeepers who permitted society

meetings on their premises were to lose their licenses. Drastic as thi«

measure appears, it must be borne in mind that the secret societies bill

was introduced as a government measure with the knowledge and consent of

Sir Charles Metcalfe. It passed the House; by a large majority, fifty

five votes being cast in favour of it and only thirteen against it.1

Nevertheless, Sir Charles saw fit to reserve it for the royal sanction,

which in the sequel was refused. It is true that the legislature had

already adopted a law of a more general nature in regard to

demonstrations tending to disturb the public peace, and that this

additional legislation was viewed by many as special legislation against

a particular class. But the ministry, as will be seen later, considered

that, under the circumstances, Metcalfe had gone beyond his

constitutional functions in withholding his assent.

Two Acts of the

session1 which elicited a general approval were Hincks's measures for

the protection of agriculture against the competition of the United

States. The latter country had recently adopted a high tariff system

whereby the Canadians found themselves excluded from the American

market. The present statute did not profess to institute a definite and

permanent policy of protection, but claimed to remedy the unequal

conditions imposed on the farming population under the existing customs

system, which put duties on merchandise but allowed foreign agricultural

produce and live stock to come in free. Under these Acts a duty of £1

10s. was to be paid on imported horses, £1 on cattle; and on all grains

other than wheat, duties of from two to three shillings per quarter.

In order to remedy the

defective operation of the existing school law two new statutes were

adopted. Fifty thousand pounds a year were now to be given by the

government to elementary schools. The difficulties which had arisen

under Mr. Draper's Act in regard to the apportionment of the government

grant were to be obviated by a division of the money between Upper and

Lower Canada in the ratio of twenty to thirty thousand pounds until a

census should be taken, after which the division was to be according to

population. In the second of the school Acts (which dealt only with

Upper Canada) it was provided that the government grant should be

distributed among the localities according to population; that the

townships (or towns or cities as the case might be) should levy on their

inhabitants a sum at least equal to, but not more than double, the

government grant. Fees were still to be charged for instruction in the

common schools, but a clause of the Act (section 49) enabled the council

of any town or city to establish free schools by by-law. The Act

continued to recognize the system of separate schools, which might be

established either by Protestants or Roman Catholics on the application

of ten or more tree-holders or householders.

The school law was

mainly in amplification and in extension of the existing system. A

measure n regard to education of a much more distinctive character, and

which evoked a furious opposition both within and without the House, was

Robert Baldwins University of Toronto bill. Although this measure was

not finally adopted, the university question remained for years in the

forefront of the political issues of the day, until the matter was

finally set at rest by the statute enacted under the second LaFontaine-Baldwin

administration.

As the name Robert

Baldwin will always be associated with the successful removal of all

denominational character from the University of Toronto, some

explanation of the question at issue is here in place. The present

University of Toronto originated in an antecedent institution called

King's College. The first impetus towards the creation of this college

had been given by Governor Simcoe, who called the attention of the

imperial government to the wisdom of making provision for a provincial

university and to the possibility of effecting this by an appropriation

of Crown lands. In 1797 the two Houses of the legislature of Upper

Canada petitioned the Crown to make an appropriation of a certain

portion of the waste lands of the colony as a fund for the establishment

and support of a respectable grammar school in each district of the

province, and also of a college or university. In 1799 the land grant

was made. It consisted of five hundred and fifty thousand, two hundred

and seventy-four acres of land. Beyond this nothing was done for many

years. Meantime a certain part of the land was set aside for special

educational objects ; one hundred and ninety thousand, five hundred and

seventy-three acres were appropriated in 1823 for district grammar

schools, and in 1831, sixty-two thousand, nine hundred and ninety-six

acres were given to Upper Canada College. At length ;n 1827 a royal

charter was issued for a university to be known as the University of

King's College. Under this document the conduct of the university and of

its teaching was vested <n a corporation consisting of the chancellor,

the president and the professors. Certain clauses of the charter gave to

King's College a denominational character: the bishop of the diocese was

to be, ex officio, its visitor, and the archdeacon of York (at that time

Dr. John Strachan) its ex officio president: the university was to have

a faculty of divinity, all students in which must subscribe to the

Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England : the same test was

prescribed for all members of the university council.

The issue of this

charter had occasioned a violent agitation. Vigorous protest was raised

against the peculiar privileges thus extended to the Church of England.

The opposition to the charter prevented any further action being taken

towards the actual establishment of the college. Finally, in 1837, a

statute2 was passed by the legislature of Upper Canada which revised the

terms of the royal charter. It provided that the judges of the court of

king's bench should be the visitors of the college, that the president

need not be the incumbent of any particular ecclesiastical office, that

no religious tests should be required of students, and that no

professor, nor member of the council, need be a member of the Church of

England. The statute still left the faculty of divinity as a part of the

university, and left it necessary for every professor and member of the

council to subscribe to a belief in the Trinity and in the divine

inspiration of the Scripture. Even after the charter had been thus

modified, a further delay was occasioned by the rebellion of 1837. and

it was not until 1842 that the building of King's College actually

commenced, the corner-stone being laid by Sir Charles Hagot in his

capacity of chancellor of the university. In April of 1843 actual

teaching had begun, the old parliament buildings on Front Street,

Toronto, being used as temporary premises. Meantime the long delay which

had been encountered in the creation of the provincial university, and

the somewhat arrogant claims that had been put forward by Dr. Strachan

and the extreme Anglicans, had led the members of the other sects to

make efforts towards the establishment of denominational colleges of

their own. The Methodists incorporated in 1836 an institution which

opened its doors at Cobourg in the following year under the name of the

Upper Canada Academy. In 1841 an Act of the parliament of Canada

conferred on the academy the power to grant degrees, and gave it the

name of Victoria College. The Presbyterians, acting under a royal

charter, established Queen's College at Kingston, which entered on the

work of teaching in 1842. The Roman Catholics had founded in the same

town a seminary known as the College of Regiopolis.

To Robert Baldwin and

those who were able to take a broad-minded view of the question of

higher education in Canada and to consider the future as well as the

present, the separate foundation of these denominational universities

appeared a decided error. It meant that, in the future, Canadian

education would run upon sectarian lines and that a narrow scholasticism

would usurp the place of a wider culture. The theologian would be

substituted for the man of learning. More than this, the present system

was in violation of that doctrine of equal rights which was the

foundation of Robert Baldwin's political creed; for the opulent land

grant enjoyed by King's College gave to it a form of state support which

was denied to its sister institutions. The measure which Baldwin

presented to the parliament n remedy of the situation was sweeping in

character. It proposed to create an institution to be known as the

University of Toronto, of which the existing sectarian establishments

should be the colleges. The executive academic body of the university

was to consist of the governor-general as chancellor, together with a

vice-chancellor and council chosen from the different colleges. With

this was to be a

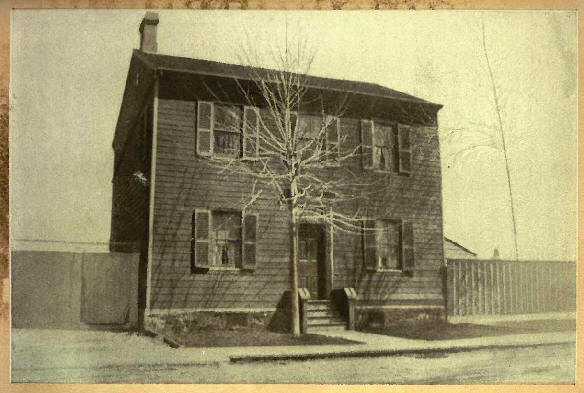

Queen's College, Kingston, 1840

board, of control made

up of dignitaries of the respective churches together with various

public officials. The essential principle of Baldwin's bill lay in the

fact that all the denominational colleges involved were put on an equal

footing. Each retained its own faculty of divinity, the university

granting a doctor's degree in divinity to graduates of all the divinity

faculties alike. The property that had been granted by the state to

King's College was to become the property of the University of Toronto.

It proposed, in a word, a general federation of the existing sectarian

institutions into a single provincial establishment looking to the state

for its support, including denominational colleges as its affiliated

members but itself of an entirely unsectarian character. To those

acquainted with the recent history of educational development in

Ontario, the wisdom of the idea of federation needs no commentary.

At the present day the

general principle of the bill —the secularization of state

education—meets with a ready support; but the proposal of the measure

aroused in Upper Canada a storm of opposition. First and foremost the

opposition came from the Anglicans, to whom the measure seemed a piece

of godless ieonoclasm directed at their dearest privileges. Dr. John

Straclian, whose intense convictions and untiring energy made him the

most formidable champion of the Church of England, led the attack on the

bill. Strachan was by instinct a fighting man who did not spare the

weight of his blows in a good cause. He forwarded to the parliament a

thunderous petition, presented by "John, by Divine Permission First

Bishop of Toronto." the intemperate language of which bespeaks the

character of the man. "The leading object of the bill," so began the

prayer, "is to place all forms of error on an equality with truth, by

patronizing equally within the same institution an unlimited number of

sects, whose doctrines are absolutely irreconcilable: a principle in its

nature atheistical, and so monstrous in its consequences that, if

successfully carried out, it would utterly destroy all that is pure and

holy in morals and religion, and lead to greater corruption than

anything adopted during the madness of the French Revolution. . . . Such

a fatal departure from all that is good is without a parallel in the

history of the world."

A whirlwind of

discussion followed the legislative progress of the bill. It was argued

that parliament had no legal right to abrogate the royal charter of

King's College; that the proposed measure was equivalent to a

confiscation of the property of the college; more than that it was

argued that the provincial parliament was not empowered to create a

university at all. These were the arguments of the lawyer, to which the

churchmen added their cry of horror at the desecration of the privileges

of the Church. The violence of "John, by Divine Permission," etc., was

imitated by lesser luminaries. "Here we have," screamed "Testis," in a

hysterical contribution to a leading Anglican paper. "the true

atheistical character of the popular dogma of responsible government.

This is its fruit, its bitter, poisonous fruit; this is the broad road

to destruction into which its many votaries are rushing headlong."

Draper in the legislative council (November 24th. 1843) opposed the bill

in a speech excellent in its masterly analysis, in which the really weak

points of the bill—its interference with charter rights and its peculiar

degrees in assorted divinity—were exposed with an unsparing hand. But in

spite of opposition from outside, the bill was making its way through

the legislature and had reached its second reading when its further

progress was stopped by an event which threw the whole country into a

turmoil of excitement. |