|

Let every man who swings

an axe,

Or follows at the plough,

Abandon farm and homestead,

And grasp a rifle now!

We'll trust the God of Battles

Although our force be small;

Arouse ye, brave Canadians,

And answer to my call!

Let mothers, though with

breaking hearts,

Give up their gallant sons;

Let maidens bid their lovers go,

And wives their dearer ones!

Then rally to the frontier

And form a living wall;

Arouse ye, brave Canadians,

And answer to my call!

—J. D. Edgar, "This

Canada of Ours."

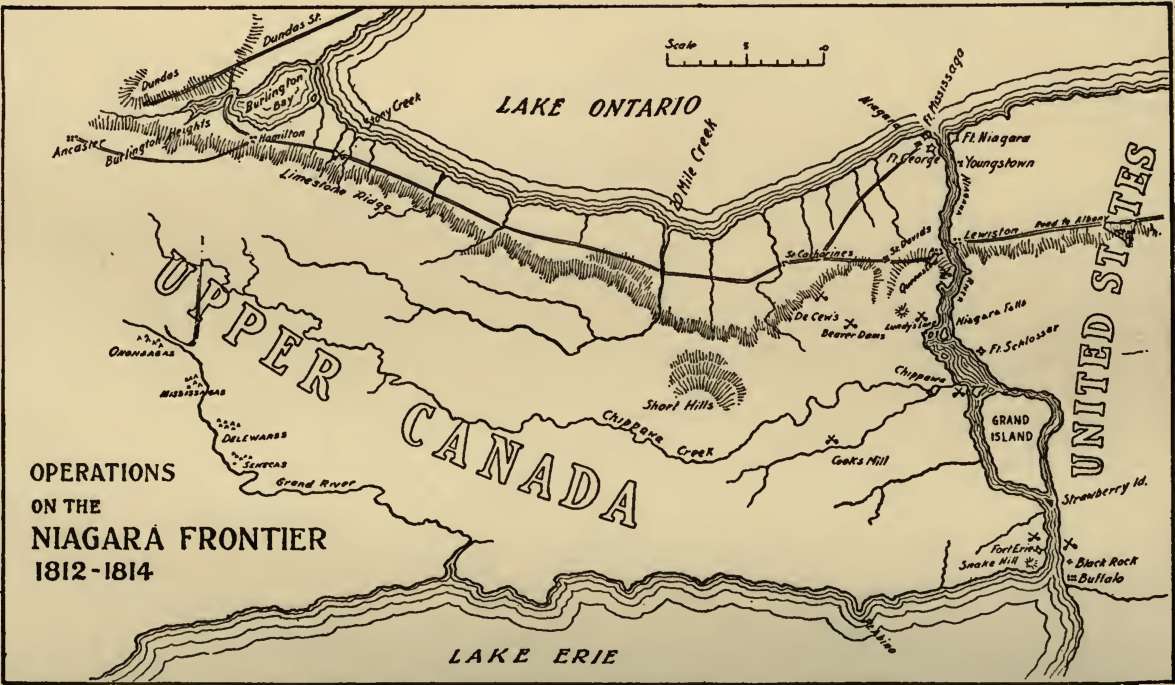

THE frontier of Canada

to be defended, reckoning from Fort Joseph at the head of Lake Huron to

Quebec, was over twelve hundred miles in length. The number of regulars

in both the Canadas was a little less than five thousand. The 8th, the

41st, the 49th, the 100th Regiments, the 10th Royal Veterans, some

artillery and the Canadian, Newfoundland and Glengarry Fencibles

composed the force, of which about fourteen hundred and fifty were in

Upper Canada, divided between Forts Joseph, Amherstburg, Chippawa, Erie,

York and Kingston. The most assailable frontier was the river Detroit

from Sandwich to Amherstburg, the river Niagara from Fort Erie to Fort

George, and the St. Lawrence from Kingston to St. Regis where the

American boundary touches the St. Lawrence. Between that place and

Quebec was an impenetrable forest. The population of Upper Canada was

about seventy thousand, of which eleven thousand might be called out as

militia, although not more than four thousand were ready for service.

This, then, was the material of which Brock had to make an army of

defence. It looked out of the question for it to be an army of attack.

Early in May a warning

note came from Mr. Thomas Barclay, the English consul-general at New

York. He mote to Sir George Prevost: "You may consider war as

inevitable. It will take place in July at the latest. Upper Canada will

be the first object. Military stores of all kinds and provisions are

daily moving hence towards the lines. Thirteen thousand five hundred

militia, the quota of the state, are drawn and ordered to be in

readiness at a moment's notice.

During this month Brock

had hurried up ordnance and other stores to St. Joseph, and had ordered

Captain Roberts, in command there, to be on his guard. At Amherstburg

there were about seven hundred militia, rank and file. The general

proposed to increase the garrison there by two 202 hundred men from Fort

George and York, and guns were sent also from those places, relying upon

others coming from Kingston by the Earl of Moira.

On June 1st General

Hull, the civil governor of the Michigan territory, and then recently

made brigadier-general, in command of about two thousand men, began his

march for the Michigan territory from Dayton, Ohio. On June 7th he

arrived at Urbana, where he was joined by the 4th Regiment.

Lieut.-Colonel McArthur, with his regiment of Ohio volunteers, had been

ordered to open a road as far as the Scioto River, where two

blockhouses, joined by a strong stockade, were called Fort McArthur.

General Hull's march lay for part of the way through thick and trackless

forests. On June 18th war was formally declared by the United States

against England, but news of this did not reach Sir George Prevost at

Quebec until the 26th of that month, and then it did not come officially

but by a letter to the secretary, H. W. Ryland, from the firm of

Forsyth, Richardson & Company, and McTavish & McGillivray of the

North-West and South-West Fur Companies. The letter was as follows:

"Montreal, June 24th. You will be pleased to inform the governor-general

that we have just received by an express which left New York on the 20th

and Albany on Sunday last at 6 a.m., the account that war against Great

Britain is declared." Fortunately General Brock was not left to learn

the news by the circuitous channel of the governor-general. He, too, had

a communication sent him by-express from Niagara. It came to Thomas

Clark from John Jacob Astor, New York, and was immediately sent on to

General Brock, who received it in York on June 26th.1 In a few hours two

companies of the 41st Regiment in garrison at York were embarked in

boats to the Niagara frontier, while the general assembled his council,

called an extra session of the legislature, and then in a small open

boat, with his brigade major, Evans, and his aide-de-camp, Captain Glegg,

crossed the lake, (thirty miles) to Fort George, where he established

his headquarters. Colonel Baynes wrote to him as soon as the

intelligence reached Sir George, and said His Excellency was inclined to

believe the report, but it was not official. Colonel Baynes also

reported that six large canoes of the North-West Company going to the

upper lakes by the Ottawa, to receive their furs, had offered to

accommodate six soldiers in each canoe, in order to reinforce St.

Joseph, but Sir George did not think it well to weaken the 49th by

sending them. The letter ends, "Sir George desires me to say that he

does not attempt to prescribe specific rules for your guidance —they

must be directed by your discretion, and the circumstances of the

time—the present order of the day with him is forbearance "

On July 3rd there was

still doubt about war being really declared, but Colonel Baynes writes

to General Brock on that date from Quebec: "We have a report here of

your having commenced operations by levelling the American fort at

Niagara. His Excellency is most anxious to hear good and recent * news

from your quarter. The flank companies here are on the march, and two

thousand militia will form a chain of posts from St. Johns to Laprairie.

The town militia of Montreal and Quebec, to the amount of three thousand

in each city, have volunteered, are being embodied and drilled, and will

take their part in garrison duty to relieve the troops. The proclamation

for declaring martial law is prepared and will speedily be issued. All

aliens will be required to take the oath of allegiance or immediately

quit the province. Our cash is at its last issue, and a substitute of

paper must perforce be resorted to."

General Brock did not

wait to receive official instructions from the commander-in-chief, but

immediately issued his orders for the disposal of his scanty force. He

called out the flank companies, consisting of eight hundred well drilled

men, and also sent an express to Captain Roberts at Fort Joseph with

instructions to attempt the capture of Michilimackinac.

The district general

order from Niagara on June 27th, was as follows: "Colonel Procter will

assume the command of the troops between Niagara and Fort Erie. The Hon.

Colonel Claus will command the militia stationed between Niagara and

Queenston, and Lieutenant-Colonel Clark from Queenston to Fort Erie. The

commissariat at their respective posts will issue rations and fuel for

the number actually present. The car brigade and the provincial cavalry

are included in this order. The detachment of the 41st, stationed at the

two and four-mile points, will be relieved by an equal number of the 1st

Lincoln militia to-morrow morning. It is recommended to the militia to

bring blankets with them on service. The troops will be kept in a

constant state of readiness for service, and Colonel Procter will direct

the necessary guards and patrols which are to be made down the bank and

close to the water's edge. Lieutenant-Colonel Nichol is appointed

quartermaster-general to the militia forces, with the same pay and

allowances as those granted to the adjutant-general."

The appointment of

Colonel Nichol to this position is another instance of General Brock's

foresight and judgment in choosing men for special work. In 1804, when

Brock was a colonel in command at Fort George, this Mr. Nichol kept, in

the village near by, a small shop or general store, where all sorts of

wares were sold. He was a clever little Scotsman, and the colonel soon

became his warm friend, and invited him often to dine with him at the

mess. At this time there was a menace of war, and Colonel Brock soon

discovered that his friend 206 had a very good knowledge of the country.

At his request Mr. Nichol drew up a statistical account of Upper Canada,

showing its resources in men, horses, provisions, and its most

vulnerable and assailable points. The sketch was in fact a military

report, embracing every detail which the commander of an army would

desire to have in the event of a war. The statement proved most valuable

in after years to General Brock, and now that he was choosing his men

for service in the various posts required, Colonel Nichol, to the

surprise of some who thought themselves entitled to the position, was

given an appointment where his particular qualities would be of use.

Lieutenant-Colonel Nichol had been in command of the 2nd Norfolk

Militia, a regiment composed almost entirely of native Americans, and

naturally not much to be depended on at the beginning of the war.

Colonel Nichol, in a letter to Captain Glegg, gives his idea of how to

manage such a regiment. He says: "You know well, sir, that in a militia

composed as ours is of independent yeomanry, it would be both impolitic

and useless to attempt to introduce the strict discipline of the line,

Just and fair conduct and a conciliatory disposition on the part of

their commanding officer will do much, and this was the line I had

marked out for myself."

Strange to say, the

official communication of the declaration of war did not reach Sir

George Prevost until about July 7th, at Montreal. He writes on that date

to General Brock: "It was only on my arrival here that I received Mr.

Foster's notification of the congress of the United States having

declared war against Great Britain." The actual declaration took place

on June 18th, 1812. The vote in the American senate was nineteen to

thirteen, while in the lower house it was seventy-nine to forty-nine. So

unpopular was it in Massachusetts that on the receipt of the news the

flags in the harbour of Boston were placed at half-mast. The declaration

of war did not reach England until July 30th, and when it arrived, the

government, thinking that the revocation of the orders-in-council would

bring a suspension of hostilities, only ordered the detention of

American ships and property. It was not until October 13th that

directions were issued for general reprisals against the ships, goods

and citizens of the United States.

Colonel Baynes writes

on July 8th, acknowledging a letter from Brock of the 3rd: "Only four

days from York." He continues, "We have felt extremely anxious about you

ever since we have learnt of the actual declaration of war, which has

been so long threatened that we never believed it would ever seriously

take place. Even now it is the prevailing opinion that offensive

measures are not likely to be speedily adopted against this country."

At that moment General

Hull, who had received news of the declaration of war on June 26th, was

preparing to enter Canada. On June 24th the American general wrote, "I

feel a confidence that the force under my command will be superior to

any which can be opposed to it. It now exceeds two thousand rank and

file." On June 30th he reached a village on the broad Miami, and engaged

a small schooner there to take the baggage on to Detroit, while he

continued his march with the troops. On July 4th his army reached the

Huron River, twenty-one miles from Detroit, and the next day encamped at

Springwells, four miles from the town. Here six hundred Michigan militia

joined him. His order from Washington was: "Should the force under your

command be equal to the enterprise, consistent with the safety of your

own post, you will take possession of Maiden, and extend your conquests

as circumstances may justify." Hull did not think himself equal to the

reduction of Fort Maiden. On the 12th he passed over the Detroit River,

and established his headquarters in Colonel Baby's house. Colonel Baby

was then absent attending to his parliamentary duties in York.

One can hardly realize

in these days of rapid communication how difficult it was then to obtain

information of what was happening in different parts of the province, or

to convey orders. Much depended on the individual capacity of those in

charge of distant posts, and a certain latitude had to be allowed them

in carrying out instructions from headquarters. Seven hundred miles from

York and about fifty miles north-east of Michilimackinac was a lonely

outpost on the island of St. Joseph, at the head of Lake Huron. A small

company of the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion was stationed here under the

command of Captain Roberts. On June 26th, from Fort George, General

Brock sent a despatch to that officer, giving him orders to attack

Michilimackinac, the island lying in the strait between Lakes Huron and

Michigan. On the 27th this order was suspended, but on the 28th it was

renewed. On the very day this letter was received, another dated June

25th arrived at Fort Joseph from Sir George Prevost, ordering Captain

Roberts to act only on the defensive. This was rather a puzzling

position for the captain, but he knew well the importance General Brock

attached to the taking of the island, and he resolved to act on the

instructions received in the letter of the 28th. He was confirmed in his

intentions by another letter from General Brock, dated July 4th, in

which he was told to use his discretion either to attack or defend.

On July 16th he

therefore set out with a flotilla of boats and canoes in which were

embarked forty-five officers and men of the 10th Veterans, about one

hundred and eighty Canadian voyageurs under Toussaint Pothier, the agent

of the Hudson's Bay Company, and a goodly number of Indians, the whole

convoyed by a brig, the Caledonia, belonging to the North-West Company.

Under cover of night they approached the white cliffs of Mackinaw. It is

a true Gibraltar of the northern lakes, accessible only on one side, and

had sufficient time been allowed, it could no doubt have been easily

defended. Its garrison consisted of sixty-one officers and men under

command of a Captain Hanks. The expedition had been so cleverly managed

that the enemy were completely taken by surprise, and at dawn of July

17th, the fort, which by the treaty of 1794 had been ceded to the

Americans, once more came under the British flag. It was the first

operation of the war, and a most important one. By it the wavering

tribes of Indians in the North-West were confirmed in their allegiance

to Great Britain, and these proved a very powerful aid in the coming

contest. Military stores of all kinds were found in the fort, also seven

hundred packs of furs, for this was the rendezvous of the traders of the

North-West. The news of this success did not, of course, reach Fort

George until the end of the month, while it was August 3rd when the

paroled men from Mackinaw reached Detroit and bore the first news of the

disaster to General Hull.

From Fort George, early

in July, General Brock wrote to the commander-in-chief that the militia

were improving in discipline, but showed a degree of impatience under

restraint. "So great was the clamour," he says, "to return and attend to

their farms, that I found myself in some measure compelled to sanction

the departure of a large proportion, and I am not without my

apprehension that the remainder will, in defiance of the law which only

imposes a fine of twenty dollars, leave the service the moment the

harvest begins."

The general, however,

knew how to deal with his homespun warriors, and instead of blaming the

men his general order of July 4th gave them the word of praise they

needed. He also gave them the word of sympathy that showed them he

realized how hard it was for them to leave their homes and their

un-gathered harvests, and spend their days and nights in tedious drill

and outpost duty, without tents, without blankets, some even without

shoes, which at that time could scarcely be provided in the country. His

order ran as follows: "Major-General Brock has witnessed with the

highest satisfaction the orderly and regular conduct of such of the

militia as have been called into actual service, and their ardent desire

to acquire military instruction. He is sensible that they are exposed to

great privations, and every effort will be immediately made to supply

their most pressing wants, but such are the circumstances of the country

that it is absolutely necessary that every inhabitant should have

recourse to his own means to furnish himself with blankets and other

necessaries. The major-general calls the serious attention of every

militiaman to the efforts being made by the enemy to destroy and lay

waste this flourishing country. They must be sensible of the great stake

they have to contend for, and will by their conduct convince the enemy

that they are not desirous of bowing their necks to a foreign yoke. The

major-general is determined to devote his best energies to the defence

of the country, and has no doubt that, supported by the zeal, activity

and determination of the loyal inhabitants of this province, he will

successfully repel every hostile attack, and preserve to them inviolate

all that they hold dear. From the experience of the past the

major-general is convinced that should it be necessary to call forth a

further proportion of the militia to aid their fellow-subjects in

defence of the province, they will come forward with equal alacrity to

share the danger and the honour." Thus he took the rough metal at his

hand, and out of it forged a weapon of strength that did good service

through three years of trial.

The position of affairs

in Upper Canada in the early part of July was extremely unpromising.

About four thousand American troops under the command of

Brigadier-General Wadsworth were on the Niagara frontier between Black

Rock and Fort Niagara, with headquarters at Lewiston, directly opposite

Queenston. A report had come to General Brock of the bombardment of

Sandwich (which was not true), but a further report came of its

occupation by the American general. President Madison announced in his

address to congress that General Hull had passed into Canada with a

prospect of easy and victorious progress. From Sandwich Hull issued a

proclamation to the people of Canada, offering the alternatives of "

peace, hberty and security, or war, slavery and destruction." Colonel

St. George, who commanded the Canadian militia on the Detroit frontier,

reported to General Brock that they had behaved badly and that many of

them had joined the invading army. There is no doubt that on that

western peninsula there were many American settlers, bound by no tie of

patriotism to Canada, whose sympathies were entirely with the United

States. A very different feeling prevailed in that part of the country

which had been mainly settled by Loyalists after the American

revolution, and also where General Brock was personally known and where

his influence extended. He wrote to Sir George his impressions about the

loyalty of the population of Upper Canada, and said that although a

great number were sincere in their desire to defend the country, there

were many others who were indifferent, or so completely American as to

rejoice in the prospect of a change of government.

Another disquieting

report came at this time of the feeling among the Indians on the Grand

River. They had heard of General Hull's successful entry into the

country, his emissaries were already among them, and they had decided to

remain neutral.

The American press was

now full of boastful predictions of the early fall of Canada. Dr.

Eustis, the American secretary of war, said: " We can take the Canadas

without soldiers, we have only to send officers into the province, and

the people, disaffected towards their own government, will rally round

our standard." Henry Clay said: "It is absurd to suppose we shall not

succeed in our enterprise against the enemy's provinces. We have the

Canadas as much under our command as Great Britain has the ocean; and

the way to conquer her on the ocean is to drive her from the land. I am

not for stopping at Quebec or anywhere else, but I would take the

continent from them. I wish never to see a peace till we do."

In the face of all this

assertion, and with a knowledge that a handful of regulars and a few

thousand undisciplined militia were all that he had to drive the

invaders back, it was hard for the general in command to keep a

confident air, and to prevent the people dependent on him from giving up

in despair. To Sir George Prevost Brock wrote: "It is scarcely possible

that the government of the United States will be so inactive or supine

as to permit the present limited (British) force to remain in possession

of the country. Whatever can be done to preserve it, or to delay its

fall, your Excellency may rest assured will be done." "I talk loud and

look big," he laughingly says in a letter to Colonel Baynes.

General Brock lost no

time in sending Colonel Procter to Amherstburg, where he was expected to

arrive on July. 21st. Of that officer he says: "I have great dependence

on his decision, but fear he will arrive too late to be of much

service." The letter, which was to the commander-in-chief, continues:

"The position which Colonel St. George occupies is very good, and

infinitely more formidable than Fort Maiden itself. Should he be

compelled to retire I know of no other alternative for him than

embarking in the king's vessels and proceeding to Fort Erie. Your

Excellency will readily perceive the critical situation in which the

reduction of Amherstburg will place me. I shall endeavour to exert

myself to the utmost to overcome every difficulty. I now express my

apprehensions on a supposition that the slender means your Excellency

possesses will not admit of diminution, consequently, that I need not

look for reinforcements. The enemy seem more inclined to work on the

flanks, aware that if he succeeds every other part must soon submit."

Just before the news

came of General Hull's occupation of Sandwich, Sir George had written to

Brock, still counselling forbearance. He said: " While the states are

not united themselves as to the war, it would be unwise to commit any

act which might unite them. Notwithstanding these observations, I have

to assure you of my perfect confidence in your measures for the

preservation of Upper Canada. All your wants shall be supplied as fast

as possible, except money, of which I have none."

Parliament was now

sitting at Quebec, and Sir George Prevost was obliged to be at that

place, while General de Rottenburg remained in Montreal. A small

reinforcement of troops had arrived in Canada, consisting of the 103rd

Regiment, a weak battalion of Royal Scots, and some recruits for the

100th. The arrival of the 103rd allowed the remainder of the 49th to

proceed to Upper Canada. "Oh, for another regiment," Brock sighed. The

naval force available in Upper Canada was a small squadron on Lake

Ontario, consisting of the Royal George of twenty-four guns, the brig

Moira sixteen guns, the Prince Regent, which had just been built and

equipped at York, and two other small schooners. On Lake Erie the Queen

Charlotte was at Fort Maiden, and the sloop of war Hunter had been sent

to the straits of Mackinaw.

General Hull's boastful

proclamation from Sandwich had not been received with the enthusiasm he

had expected from the population of Upper Canada. A counter appeal had

been issued from Fort George by General Brock, ending in these words:

"Beholding, as we do, the flame of patriotism burning from one end of

the Canadas to the other, we cannot but entertain the most pleasing

anticipations. Our enemies have indeed said that they can subdue the

country by a proclamation, but it is our part to prove to them that they

are sadly mistaken; that the population is determinedly hostile, and

that the few who might be otherwise inclined will find it to their

safety to be faithful."

It was well to be

cheerful and confident in the face of the difficulties that surrounded

him, and this spirit was shared by his followers. Once more he writes to

the commander-in-chief: "The alacrity and good temper displayed when the

militia marched to the frontier has infused in the minds of the enemy a

very different sentiment of the disposition of the inhabitants, who he

(the American general) was led to believe would, on the first summons,

declare themselves an American state."

On July 20th news came

of an unexpected success. It will be remembered that General Hull on his

march to Detroit had left his heavy baggage and stores to be conveyed by

a schooner, Cayahoga, from the Miami River to Detroit. The boats of the

Hunter, under the command of Lieutenant Rolette, came across this

schooner and succeeded in capturing it. General Brock wrote at once to

Sir George Prevost to tell him that Colonel St. George had reported the

capture and had sent him some interesting documents found on board. From

the correspondence taken he judged the force at Detroit to consist of

about two thousand men. It was reported also that the enemy were making

numerous and extensive inroads from Sandwich up the river Thames. He had

therefore sent Captain Chambers with about fifty of the 41st to the

Moravian town, where he had directed two hundred militia to join him. He

was most anxious to set off himself for Amherstburg, but was obliged to

wait for the meeting of the legislature, which was summoned for July

27th.

As to making an attack

on Fort Niagara, which had been suggested, General Brock did not think

it was of immediate consequence. He writes: "It can be demolished when

found necessary in half an hour." His guns were in position and he

considered his front to be perfectly safe. In the meantime he was

devoting himself to the training of the militia, to enable them to

acquire some degree of discipline.

On July 22nd from Fort

George, General Brock issued another proclamation as president of the

province. It ran as follows: "The unprovoked declaration of war by the

United States of America against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and

Ireland has been followed by the actual invasion of this province, in a

remote frontier of the western district, by a detachment of the armed

forces of the United States. The officer commanding that detachment has

thought proper to invite His Majesty's subjects not only to a quiet and

unresisting submission, but insults them with a call to seek voluntarily

the protection of that government.

"Where is the Canadian

subject who can truly affirm to himself that he has been injured by the

government of Great Britain in his person, his liberty or his property?

"Where is to be found in any part of the world a growth so rapid in

wealth and prosperity as this colony exhibits, settled not thirty years

ago by a band of veterans exiled from their former possessions on

account of their loyalty? Not a descendant of these brave people is to

be found who under the fostering liberality of their sovereign has not

acquired a property and means of enjoyment superior to what were

possessed by his ancestors. This unequalled prosperity could not have

been attained by the utmost liberality of the government or the

persevering industry of the people, had not the maritime power of the

mother country secured for its colonists a safe access to every market

where the produce of their labour was in demand.

"The unavoidable and

immediate consequence of a separation from Great Britain must be the

loss of this inestimable advantage. What is offered you in exchange? To

become a territory of the United States and share with them that

exclusion from the ocean which the policy of their present government

enforces. You are not even flattered with a prospect of participation in

their boasted independence, and it is but too obvious that once excluded

from the powerful protection of the United Kingdom, you must be

re-annexed to the Dominion of France, from which the provinces of Canada

were wrested by Great Britain, at a vast expense of blood and treasure,

from no other motive than to relieve her ungrateful children from the

oppression of a cruel neighbour. This restitution to the empire of

France was the stipulated reward for the aid afforded to the revolted

colonies, now the United States. The debt is still due and there can be

no doubt the pledge has been renewed as a consideration for commercial

advantages, or rather, as an expected relaxation in the tyranny of

France over the commercial world. Are you prepared, inhabitants of Upper

Canada, to become willing subjects, or rather, slaves to the despot who

rules Europe with a rod of iron? If not, arise in a body, exert your

energies to cooperate cordially with the king's regular forces to repel

the invader, and do not give cause to your children, when groaning under

the oppression of a foreign master, to reproach you with having too

easily parted with the richest inheritance on earth—a participation in

the name, character and freedom of Britain.

"Let no man suppose

that if in this unexpected struggle His Majesty's arms should be

compelled to yield to an overwhelming force, the province will be

abandoned. The endeared relation of its first settlers, the intrinsic

value of its commerce, and the pretensions of its powerful rival to

repossess the Canadas, are pledges that no peace will be established

between the United States and Great Britain of which the restoration of

these provinces does not make the most prominent condition."

On July 27th General

Brock returned to York, where, attended by a numerous suite, he opened

the extra session of the legislature. His speech on that occasion rings

like a trumpet note: "Gentlemen of the House of Assembly, we are engaged

in an awful and eventful contest. By unanimity and despatch in our

councils, and vigour in our operations we may teach the enemy this

lesson, that a country defended by free men enthusiastically devoted to

the cause of their king and constitution, can never be conquered!" |