|

THE name and titles

of the Earl of Selkirk are firmly attached to a number of localities

in the Canadian West: a town and county of Manitoba, a. range of

mountains in British Columbia, a fort on the Yukon River, and an

island in Lake Winnipeg, all bear the name of Selkirk; a part of the

city of Winnipeg called Point Douglas, where originally stood Fort

Douglas, preserves to this day the family name of the great

colonizer. The ruins of a fort near the international boundary,

known as Fort Daer, long remained to recall one of the titles of the

noble house of Selkirk.

The man who thus

impressed himself upon so vast a region was no common man, and the

story of his life is worthy of a place in the treasure-house of

Canadian and British worthies.

Thomas Douglas, fifth

Earl of Selkirk, Baron Daer and Shortcleugh, was a scion of one of

the oldest Scottish noble families. As the writer has said

elsewhere, "The intrepidity of the Douglases, the perseverance of

the ancient family of Marr, and the venturesomeness of the house of

Angus, were all his inheritance by blood. Back nineteen generations,

and not less than seven hundred years before his time, Theobald, the

Fleming—the Selkirk ancestor—scorned the quieter pleasures of home,

and went to seek his fortunes among the Saxon people of old

Northumbria, bought himself a new home with the sword, and the lands

of Douglas were granted him because he had won them honourably."

Time does not permit to tell the deeds

of Theobald's great grandson, Sir William Douglas, the hardy man who

joined the unlucky Wallace, and suffered death for it, and of Sir

William's grraiidson, the grim Sir Archibald. James, the second earl

of Douglas, who fell fighting against the Percy, was the brave hero

of the battle of Otterburn. It was his dying boast that "few of his

ancestors had died in chambers." Good Sir James Douglas lived in the

days of the Bruce, distinguished himself at Bannockburn, and figured

in the attempt to carry the heart of King Robert to Jerusalem. These

might suffice for a group of ancestors of remarkable distinction,

but there was also that other famous man, Archibald, "Bell the Cat,"

the Earl of Angus, whose courage and resource have become watchwords

in history.

With such heroic blood in his veins our great colonizer was born,

being the seventh son of Dunbar, fourth Earl of Selkirk. He was born

in June, 1771, at St. Mary's Isle, the earl's seat at the mouth of

the Dee in Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland. At the age of fifteen young

Thomas Douglas went to the University of Edinburgh, and there

pursued his studies till he was nineteen. His college days gave

promise of an energy, resourcefulness, and ability which were to

urge him to great achievements in his later days. With Walter Scott

he was a member of "The Club," a small society of ardent literary

spirits. The earl, young Thomas's father, was a broad-minded man,

who showed favour to rising genius, and patronized Robert Burns. It

was at St. Mary's Isle that Burns, on being entertained,

extemporized the well-known "Selkirk Grace" found iii his poems.

On another occasion the poet Burns, a

guest at Ayr of Dugald Stewart, the great metaphysician, there met

Lord Daer, an older brother of Thomas Douglas, and was so captivated

by him that he wrote a poem concerning him, in which he says:—

"Nae honest, worthy mail need care

To meet with noble, youthful Daer,

For he but meets a brother."

Amongst the companions of Thomas Douglas

in the little club of nineteen in Edinburgh were men afterwards

greatly distinguished: William Clerk, of Eldin, Sir A. Ferguson,

Lord Abercromby, and David Douglas, afterwards Lord Reston.

At the close of his college career, the

young nobleman, who had a great sympathy for the downtrodden and

oppressed, found his way to France, and was disposed, like many

British Liberals, to extend his approbation to the leaders of the

French Revolution. It may be of interest to give here a letter

written by him to his father, the Earl of Selkirk.

"DEAR FATHER,—We are all here very

quiet, tho' your newspapers have probably by this time massacred

half of Paris. The disturbance of which Daer gave you an account is

completely settled. The measure M. de la Fayette took of breaking

one of the mutinous companies of the Garde Soldee was indeed much

criticized in the Groupes of the Palais Royal, but the ferment is

blown over, and will probably be put out of their heads by the

Avignon business. I was at the National Assembly the whole three

days they discussed it (one of which they sat 12 hours). It is

carried by a great majority that they are not to unite it at once to

France as the Jacobins wished.

I have no more time as the post is just

going. "Yours,

"Thomas Douglas."

On his return from France young Thomas

Douglas went, as seems to have been his custom during his college

course, to spend his summer in the Highland straths and valleys. He

had become extremely fond of the Highland people, and although a

Southron learned the Gaelic language.

In 1797, on the death of his brother,

Lord Daer, young Douglas, who was then the sole survivor of the

family of seven sons, was made Baron Daer and Shorteleugh, and two

years afterwards, on the death of his father, he became Earl of

Selkirk. His youthful enthusiasm was now, at the age of

twenty-eight, very great, and the wealth and influence placed at his

disposal as a British earl turned his thoughts to benevolent and

noble projects.

It was now the beginning of the

nineteenth century, and all the accounts of that period agree in

saying that there was great distress among the British people.

The sympathetic heart of the

philanthropic young man had been touched by the sufferings of his

Highland countrymen. The Napoleonic wars had been especially hard

upon the Highlands, but an economic wrong also set on fire the

Highland heart. Men can be found in Canada to-day whose indignation

rises when the "Highland Clearances" of the early years of the

nineteenth century are mentioned. The "Clearances" were the result

of a policy adopted by the great landholders of the north of

Scotland to diminish the large number of small crofts or holdings,

and to make wide sheep runs for rental to a few proprietors, who

with larger capital might better develop the resources of their

estates. This policy could not fail to bear heavily upon the poor.

The Highlander has a passionate attachment to his native hills, and

his shielan, poor as it is, is his home. In the lament of the

Highlanders, it was said in their Gaelic idiom that "a hundred

smokes went up one chimney," meaning that only one house now stood

where a hundred had formerly been seen.

The heart of the young earl was deeply

touched, and he forthwith laid plans for a systematic emigration

policy which should bring relief to his unfortunate countrymen, and

to the suffering people of the neighbouring island of Ireland. Our

next chapter will treat iii greater detail of the earl's schemes of

emigration; suffice it now to say that these are embodied in his

most elaborate work on emigration, [Observations on the Present

State of the Highlands of Scotland, with a View of the Causes and

Probable Consequences of Emigration. London, 1805.] to which we

shall again refer.

There seems to have been a spirit of

marvellous enterprise in Lord Selkirk which expressed itself in

plans and projects of improvement, and in discussion of public

affairs of the greatest moment. To a patriotic Briton the first

decade of the nineteenth century gave abundant cause for anxiety.

Napoleon, with "Europe-shadowing wings," threatened at any moment to

swoop down on the British Isles. The attempt of the French fleet to

land at Bantry Bay in Ireland in 1796 had been trifling enough, but

now Napoleon's added allies made him far more formidable.

Accordingly Lord Selkirk in his place in the House of Lords, in

1807, laid before his fellow-legislators a plan of defence for the

empire. "Every young man," said he, "between the ages of eighteen

and twenty-five, throughout Great Britain, should be enrolled and

completely trained to military discipline." His Lordship estimated

that of the population of Great Britain and Ireland, then put down

as about eleven million, upwards of six hundred thousand were

between the ages named and eligible for this purpose. The training

would proceed in succession. For three months officers would train

one-fourth of those within their districts; and so on with the

second quarter, till all would have secured twelve weeks drill, in

the year. Once a year a general assemblage would take place at a

fixed time, and the trained men be kept in form, by the drill

required. With due regard to the interests of the agriculturists,

the beginning of summer would be selected as the time of general

assemblage.

This remarkable scheme was developed with a minuteness of detail and

a clearness of statement quite wonderful in a man not trained to

military affairs. It is a tribute to his acuteness, and to his grasp

and foresight, that the main points of the plan he outlined are now

in force throughout a great portion of Europe.

In the following year the earl developed

his ideas on this subject in a brochure of some eighty pages,

bearing the title, "On the Necessity of a more Effectual System of

National Defence." In publishing this work Lord Selkirk had the

assistance of his kinsman, Sir John Wedderburn, afterwards of the

East India Service. It is interesting to note that in republishing

this work more than fifty years afterwards, Sir John could do so,

finding it strikingly applicable to the conditions then prevailing.

Sir John, in referring to the Earl of

Selkirk, calls him "a remarkable man, who had the misfortune to live

before his time." While this may refer to the trials which

afterwards overtook Lord Selkirk, we question very much whether His

Lordship's schemes were as chimerical and ill-considered as this

statement would imply.

This period of Lord Selkirk's life was

certainly one of great activity. After his publication of his scheme

of defence, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society, and it was

perhaps this circumstance which stimulated his literary activity. In

any event we are justified in attributing to him two anonymous works

which anticipate his later acknowledged views as contained in his

"Sketch of the British Fur Trade in 1806." In these two books,

"Observations on a Proposal for forming a Society for the

Civilization and Improvement of the North American Indians within

the British Boundary" (1807), and "On the Civilization of the Indian

in British America" (no date), the author advocates the

establishment of schools in which young Indians might be instructed,

not only in ordinary branches, but also in industrial pursuits. He

would have had certain portions of the country set apart for the

Indians alone, he would have had the "legislature applied to for an

Act to authorize the governor of Canada to fix by proclamation the

limits of the country reserved for the use of the Indian nations,"

and he would have secured the total suppression of the liquor

traffic, whose ravages among the Indians he describes in startling

colours. \\Te

read these details with surprise, for we see them all embodied in

the Reserve System, the Industrial Schools, and the law making it

illegal to give or sell strong drink to an Indian, in fact, in the

main features of the policy carried out so successfully in Western

Canada during the last twenty-five years of the nineteenth century.

It is unjust to contend that the propounder of such practical ideas

lived before his time.

In 1809 Lord Selkirk succeeded in

gaining the attention of the public men of his time in a pamphlet

published by him, entitled "Parliamentary Reform," which he

addressed to the chairman of the committee at the "Crown and

Anchor," presumably a Whig organization. The house of Selkirk was

Whig, or Liberal, in its views. This may be seen by any one who

reads the work mentioned on emigration. The expansive and altruistic

spirit shown in the work was quite in harmony with the large-hearted

and sympathetic views which we attribute to the writer. But as every

student of political science knows, the excesses of the French

Revolution, the rancour of political parties, and the evident

discontent in the United States that followed the first generation

of democratic rule, chilled the ardour of lovers of liberty in all

lands about the beginning of the nineteenth century. Men like

Coleridge and Wordsworth, who had looked to the French Revolution to

break the chains of tyranny, not only in France but for the whole

world, saw with dismay the terrorism of a mob replaced by a great

military despotism, and they shuddered at and forsook principles

they had formerly advocated.

So with Lord Selkirk. He states to the

men of the "Crown and Anchor" that his father and brother had been

zealous friends of a parliamentary reform, and that all his early

impressions were in favour of such a measure. "he had thought," he

says, "that if the representation were equalized, the right of

suffrage extended, the duration of parliaments shortened, bribery

could scarcely be applied with effect." "But," says he, "I have had

an opportunity (in the French Revolution and in a visit to America)

which my family never had of seeing the political application of

those principles from which we expected consequences so beneficial.

With grief and mortification I perceived that no such advantages had

resulted as formerly I had been led to anticipate." Lord Selkirk

accordingly refused to take part in the proposed agitation, and,

indeed, went further and threw in his lot with the reactionary

party. We have

thus sought to give a picture of the mental characteristics of this

public-spirited philanthropist. He was mentally most acute and

active, indeed his mind burned itself out iii activities and

projects that to some seemed visionary. But lie was a man of deep

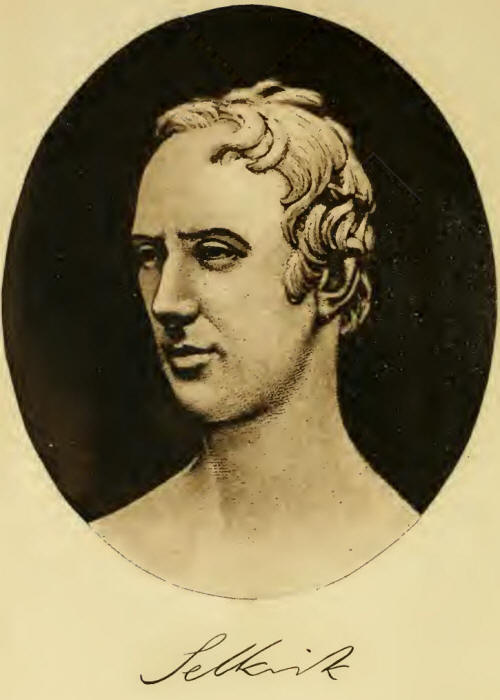

thought and large heart. As we look upon the marble bust chiselled

by Sir Francis Chantrey, the great English sculptor, now at St.

Mary's Isle, we see the indications of intellectual fineness and

keenness of mind, as well as of a generous and pitiful heart.

Author, patriot, colonizer, and

philanthropist—his enthusiastic devotion to his projects possesses

us, and we seem to see the "tall, spare man, full six feet high,

with a pleasant countenance," as he came to Helmsdale to bid the

Highland emigrants to his colony farewell; as he afterwards stood on

the banks of the Red River and apportioned his colonists their lots;

as lie dealt with the bands of Indians of the West, who sealed a

perpetual covenant with him whom they named their "Silver Chief." We

shall follow him with interest through the many phases of his

eventful though somewhat sorrowful life. |