|

"Every Scottish man has

a pedigree. It is a national prerogative as inalienable as his pride and

his poverty." I commence these memoirs, as the Author of Waverley

commenced his autobiography, for I think that a sketch of the ancestry

of James Murray, which I hope may not in itself want in interest, cannot

fail to aid in forming a true estimation of the man himself. Heredity

counts for much even in our day, and was more marked in its effect at

the time of which I am writing. In Scotland, particularly, the

continuance of the feudal system up to a late date of the eighteenth

century made the line dividing the scions of the noble houses from those

who were their dependents more clearly defined than can be easily

pictured to-day, and could not fail to induce a sense of command in

those brought up in such a school.

The "Scottish man" who

treasured the history of his family was imbued with its traditions and

bore himself accordingly. A highland chief in those days was a law unto

himself, subject to the central authority of the Crown in so loose a

fashion, that government consisted more in producing a balance of power

in a series of minor states that, in authoritatively ruling them. In the

lowlands, with which I am immediately concerned, the Sovereign's power

extended further, but here also the legacy of border warfare

and of blood feuds between

various families had served to maintain the idea, even when the fact

hail vanished, that the strong man armed keepeth his house in peace.

The family of Black

barony, of which our family of Elibank is a branch, claim descent from

the some source as the noble family of Atholl. and if William de Moravia

ranks in relation to a number of Scottish families in somewhat similar

degree as Brian Boroihme to as many in Ireland, I have no intention of

bringing reproof on my head from descendants of cither hero (the more

so. as I claim both myself!) by casting any doubts on the authenticity

of the pedigree. I therefore propose to skip various generations of

Moravia, Moray, and Murray, and come at once to Sir Andrew Murray of

Blackbarony, who was the head of that ancient family in the first half

of the sixteenth century.

Sir Andrew succeeded to

the family honours as an infant in 1513, when his father fell on Flodden

side; and during his lifetime maintained his rights in the good old

simple plan, like most of his neighbours. By his second wife, Grizel

Bethune, he became the father of Gideon Murray, his third son, who was

first of Elibank, and with whom this history properly commences; but

before parting with Sir Andrew and his wife I cannot forbear, at the

risk of a digression, from putting in my record some recollections of

the romantic history which this union brought into the ancestry of my

hero.

Grizel Bethune was one

of the younger daughters of John Bethune or Beaton of Criceh, in

Fifeshire, and the name brings us at once into close touch with the

tragic story of Mary of Scotland. Her two elder sisters were Janet, and

Margaret, Lady Forbes of Reres, and about these a host of memories

arise. Janet was a lady of matrimonial proclivities, her third husband

being Walter Scott of Buccleugh, known to fame as "Wicked Watt," for,

indeed, nearly all Scotts were Walters, and it was very necessary to

bestow on them distinctive epithets. Wicked Watt was murdered in

Edinburgh in 1552, and Janet as

his widow, whose "burning pride and high

disdain forbade the rising tear to flow," is the heroine of the Lay of

the Len t Minstrel; but her claim to historic famo rests rather on her

connection with Mary Stuart than on the poet's licence of Sir Walter

Scott. It was she who was known as the "Auld Witch of Buccleueh," she

who was alleged to have cast love spells round the unfortunate queen to

encompass the marriage with Bothwell, a story we may reject right off as

originating in the evil tongues of the day which were many and sharp,

for it is at least certain that she parted in anger from her Royal

mistress immediately after the disastrous event; she to whom scandalous

tongues attributed love affairs with Bothwell himself, though she was

quite old enough to be the mother of that "glorious, rash, hazardous

young man," nevertheless it is curious that both she and Bothwell had

the reputation of dabbling in i black magic," and the lady at least was

credited with powers to call " the viewless forms from air." It was

Janet, too, from whom originated the story in the Reiver's Wedding, that

she laid before her hungry retainers a dish containing just a pai r of

silver spurs, as a delicate hint that it was time to bo up and doing,

and Cumberland beef was to be had for the taking. No doubt she was a

redoubtable lady, quite capable of leading her Scotts on a foray, and of

showiiig the truth of the maxim that "nothing came amiss to a Scott that

was not too heavy or too hot."

Lady Forbes of Reres

was a close companion of Mary's, and fortunately we can dismiss as mere

scandal the stories retailed by that mince of ungrateful liars, Master

George Buchanan. She was the " fat massy old woman " that Buchanan

alleges was let down by a "string" over the w all of the Exchequer House

at Edinburgh when on a disgraceful errand to Bothwell—though why she

should not have taken the more reasonable method of going through the

gate by which Bothwell returned with her is not explained. When Buchanan

embellishes his story with the detail that the "string" broke and the

"massy old woman" fell the rest of the way, one wonders how it comes

that some historians of repute have quoted him to "prove" the case

against poor Mary.

Lady Forbes, too,

figures in that famous "casket letter," which it is falsely alleged was

addressed by the Queen to Bothwell, wherein the supper party is

described and much made of Mary's description of it; how Lord Livingston

"thrust her in the body" and made a remark which has been interpreted by

her enemies much to her disadvantage. After all "thrust" only means

nudged, and Livingston's remarks are capable of a perfectly innocent

rendering.

Then there were many

other Beatons in the story. James, Mary's faithful ambassador in Paris;

John his brother, who devoted his life to her, and died in her service

during her captivity in England; and Mary, who lives in song as one of

the four Maries—all were faithful to their sovereign.

With all these

interesting personalities our Sir Andrew became connected by his

marriage with Grizel Bethune, and at the same time with the house of

Buccleuch, for Grizel when he married her was the widow of William

Scott—the strange fact being that the sisters Janet and Grizel were the

wives respectively of father and son. Thus it came about that when

Grizel bccame the mother of Gideon Murray, afterwards of Elibank, the

young stranger found himself nephew to the famous ladies referred to

above, and half-brother to the Lord of Buccleuch, another Walter Scott.

I like to picture the young Gideon at Branxholm, when that famous

stronghold was rebuilt by his half-brother after its destruction by

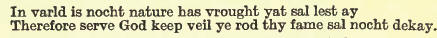

Sussex, and to think that he saw the chiselling of that inscription over

the arched doorway—

and no doubt found it a

good motto to remember, and one which we maybe sure was well known to

his descendants.

Perhaps it was here

that he acquired that taste for architecture that enabled him many years

later to repair the king's palaces at Holyrood and Falkland at small

cost, which mightily pleased his Majesty, who examined his expenditure

with all the care of a canny Scot.

Gideon Murray was

intended for the Church, and even got so far as to be "presented" to the

parish of Auchterles in 1582, an office which carried with it the

position of Chantor of Aberdeen. However, his spiritual career was cut

short by an "accident," for it is recorded that "Mr. Gideon Murray,

Chantor, quha cannot be comptit ane of the Chapter, because for

slauchtir he was fugitive out of the North and never returned ther agane."

The accident was the killing of a man named Aichcson, though how our

Gideon came to forget his cloth so far is not recorded. However, the

fact drove him to seek another outlet for his energy, and we next find

him in the capacity of guardian to the son of his deceased half-brother,

still another Walter Scott, and particularly in a famous skirmish

between the Wardens of the Marches, known in border story as the

"Lockerbie Lick," in which the Scotts and Johnstons were victorious over

the Maxwells. However, though more successful as a soldier than as a

cleric, Gideon had still to find his real vocation, and throughout the

succeeding years he appears as the faithful and trusted councillor of

King James VI.

It is said that he owed

his advance in the favour of his Sovereign to the influence of his "near

relation," Robert Ker, afterwards Earl of Somerset, but family tradition

holds that his advancement was due to the king observing his faithful

discharge of his duties in connection with Buccleuch, and his being

desirous of utilising his ability and honesty, the latter being a

qualification not very readily obtainable at. the time. This latter

version is more acceptable, having in view the somewhat unsavoury

character of Somerset, and indeed the "near relationship" referred to by

Sir Walter of Abbotsford was not so very near after all, for Somerset

was the son of Janet Scott, a half-sister of Buccleuch's, and no blood

relation at all to our Gideon. Be that as it may, his advance was rapid.

Knighted in 1605, he was Justiciary of the border in the same year, and

in 1607 the Privy Council passed an Order approving of his services in

preserving the peace of the Marches.

But the old Adam was

not dead, and I must refer to the remarkable story, which has been so

often repeated that it stands a good chance of becoming true, wherefore

I repeat it again for the express purpose of running a tilt at it.

According to Sir Walter of Abbotsford, the incident, which must have

occurred in 1610, if it occurred at all, concerned the Scotts of Harden,

the head of which family was Sir Walter, commonly known as "Auld Watt."

It appears that Auld Watt cast the eyes of desire on Sir Gideon's fat

cattle, and evidently having little respect for the worthy knight's

position as guardian of the peace, sent his son William to annex as many

of the said cattle as he conveniently could. Sir Gideon, however,

happened to be at home, and no doubt with a good experience in similar

ventures was not to be caught napping, and having captured the

adventurer, was about to hang him on the "doom tree," which we are to

suppose was handy at the castle gate, when his more considerate and

far-seeing dame interposed saying, (I quote Sir Walter), "Haut na. Sir

Gideon, would you hang the winsome Laird of Harden, when ye have three

ill-favoured daughters to marry?" The Baron "catehed at" the idea, and

replied, "Right, he shall either marry our daughter mickle-mouthed Meg

or strap for it." Upon this alternative being proposed to the prisoner

he at the first view of the case stoutly preferred the gibbet, but, to

shorten the story, finally consented and married the young lady.

And now for my tilt! To

begin with, Sir Gideon had only one daughter, and her name was Agnes;

and to go on with, her marriage with William Scott of Harden took place

m 1611 under the most leisurely of legal and contractual formalities.

The marriage contract, which is preserved by her descendant, Lord

Polwarth, is, I believe, seven feet long and minutely written; and to

end up with, Sir Gideon provided what was a more than usually handsome "tocher"

of 7000 merks Scots, and more also, the lady had a ' curious hand at

pickling beef," a very desirable art when "consignments" came in in

quantity at irregular intervals! I leave the impartial reader to judge

how much truth there may be in the aspersions cast on the personal

attractions of my collateral ancestress, but should the judgment be

adverse, and in mitigation of sentence, let me mention that her

new-found mother, "Auld Watt's" wife, was the beautiful Mary Scott,

renowned on the border as the "Flower of Yarrow," so let us hope Agnes's

descendants, who were both numerous and distinguished, found, if

necessary, a corrective as to their personal appearance on the paternal

side. They had odd nicknames in those days. Agnes's sister, in her new

family, was known to fame as Meggie Fendie, and it was her fate to marry

"Gibby" Elliott of the "Gowden Garters," and to become the ancestress of

the noble house of Minto.

Rut to return to Sir

Gideon. In 1612 he was appointed Treasurer Depute, and Controller and

Collector Depute of the Kingdom, and as Somerset, who was Lord High

Treasurer, was very much engaged elsewhere, and paid very little

attention to his business, it can be safely assumed that Sir Gideon

conducted the duties of the office entirely. In 1613 Sir Gideon was

appointed a Lord of Session, with the title of Lord Elibank.

In 1618 he was a member

of that momentous assembly at Perth which passed the Five Articles.|

Whether he was one of those who advised the king to follow a moderate

course in respect of the Articles is not recorded. His early connection

with Aberdeen, and the habit gained by contact with the king, makes it

certain that he belonged to the Prelatic party, and there were few among

them who foresaw the cataclysm that followed, which ultimately destroyed

the throne and affected the fortunes of his son and his descendants

disastrously. Whether or not his action in this and other similar

matters was the cause, Sir Gideon did not arrive at his present position

without creating enemies. "Neither the wealthy, the valiant, nor even

the wise, can long flourish in Scotland; for envy obtaineth the mastery

over them all." So it was with Sir Gideon; in the year 1621 an

information was laid against him for abusing his office to the king's

prejudice. An account of the circumstance is given by Archbishop

Spottiswood in his History of the Church in Scotland, from which it

appears that the information was laid by James Stuart of Ochiltree, who,

it appeared, had been treated with too much strictness by Sir Gideon in

connection with certain revenues for which he was responsible, and the

matter was submitted for trial. Sir Gideon, "being of great spirit, and

taking impatiently that his fidelity, whereof he had given so great

proof, should be called in question on the information of a malicious

enemy, by the way, as he returned from Court did contract such a deep

melancholy as neither counsel nor comfort could reclaim him . . . and so

after he came to Edinburgh within a few days departed this life. It was

not doubted if he should have attended the trial, but he had been

cleared, and the accusation proved a mere calumny; nor was it thought

that the king did trust the information, but only desired to have the

honesty of his servant appear. . . . By his death the king did lose a

good servant as ever he had in that charge; and did sore forethink that

he should have given ear to such dilations,"

and, finally, as

Spottiswood quaintly puts it, "The gentleman alwaies died happily and

had his corps interred in the Church of Ilalcrudhouse."

With that conspicuous

quality of being too late, which characterised the Stuarts, the king

made "amends" by the issue of a letter under the Great Seal, "making

mention that His Majesty, calling to mind the true and faithful service

done to His Majesty by Umquhile Sir Gideon Murray of Elibank, Knycht . .

. and to make an honourable remembrance that others by his example may

be moved by the like care and fidelity, and therefore His Majesty of

certain right and proper motion, with advice and consent of the Lords of

His Majesty's present Council, finds and decrees that said Umquhile Sir

Gideon Murray . . . during the whole time and period thereof from his

first employment to his decease behaved himself therein faithfully and

diligently as became a loyal subject and dutiful servant . . . and

declares him and his heirs free of all imputations, calumnies, or

aspersions whatsoever, whereby his person, name, fame, goods, lands or

posterities may in any sort be taxed, scandalised, or endangered. . . ."

With this eulogy of the

character of Sir Gideon we will leave him. If ancestry be a sound basis

for biography, I can have no better foundation for my subject than this

sketch of the life of the founder of the House of Elibank, and in much

that has been said of Sir Gideon, and much more that might be said,

there are similarities to the character and history of him whose life

will be written here. Like his ancestor, he served his king doggedly,

and did what he had to do without fear, favour, or affection, and like

him it was his fate to suffer from the effect of religious controversy,

and like him, too, his reward for distinguished service was to be

dragged before a public tribunal on the "information of a malicious

enemy," in order that his "honesty might appear." "Virtute Fideque"—by

courage and faithfulness—was the motto bestowed on the house by King

James and James Murray worthily maintained the tradition.

During the latter years

of Sir Gideon's lifetime a new spHt had found place in the Scottish home

life, the effect of which should be briefly noticed here. The death of

Elizabeth and accession of James to the dual Crown brought to lowland

Scotland the beginnings of two remarkable changes: the one, which tended

to peace, was the gradual suppression of the border warfare; the other,

which had the opposite effect, was the disturbance of the religious

equilibrium of the people. In a sense the one reacted on the other; the

border and family feuds were, it is true, replete with tragedy, but they

had a kind of grim humour which suited the temper of the combatants, and

at least left them ready to combine in the face of a common enemy, and a

sufficient devotion to the Sovereign whose power was not exercised at

too close quarters. They acted as a kind of safety valve to a people

whose aspirations were confined in narrow channels. For the Scot there

were few questions of foreign politics. Colonisation projects did not

demand his thought and energy. Scottish fleets were not to be found in

every sea providing the news-sheets with tales from the world beyond;

trade was of meagre dimensions, and in the hands of a few; communication

between different parts of the country scarcely existed. It is true that

many of the young men found congenial employment in the foreign armies,

but until the closing scenes of the Thirty Years' War, not many of them

returned to bring a new spirit of militarism, and when they did, it was

to find that a new order of things had arisen demanding their employment

in a controversy not very dissimilar to that they left behind them on

the Continent of Europe.

And yet in the soul of

this people lay, as yet unborn, a genius for trade, manufacture,

invention, and agriculture; a fixity of purpose, an indomitable

perseverance, which has since made them known the world over. Looking

backwards, with history crystallised before us, it is easy to see what

the Stuarts might have done. What they did was to stifle the awakening

life of the people and to sow in it, and force into unnatural growth

with an insane tenacity of purpose, the seed of bitter religious

controversy, which divided the nation sharply into two parties and

alienated the majority from the old allegiance which was at one time

their heritage; a controversy into which the opponents entered with

astonishing vehemence, partly because a fanatical obstinacy was part of

their nature, but chiefly because other and more advantageous outlets

for their instincts were denied them.

Thus it came about that

when Gideon's eldest son, Patrick Murray, reached manhood he found a

stormy horizon, and the necessity for choosing a side. It is scarcely

necessary to say that with his inherited instinct he became a king's man

and followed the fortunes of the unfortunate monarch who afterwards

succeeded to the throne. It is not certain in what capacity he rendered

his first services, but a document is preserved showing that as early as

1615 King James had bestowed a "pension" on him for "true and faithful

service," and "to give him better occasion to do the like in time

coming," words which almost seem to contain a prevision of the

approaching storm. At that Session of the Estates held in 1621, which

ratified the famous "Five Articles" already accepted by the General

Assembly, Patrick, now Sir Patrick, voted with the majority, and no

doubt took a part in that too eager enforcement of the " Innovations,"

the effect of which I have already referred to. In 1628, the year in

which the king's action to resume the Church revenues came before the

Estates, Sir Patrick was advanced to the dignity of baronet, doubtless

for services in connection therewith.

It is a matter of

history that the king's intention was never carried to finality.

Ostensibly, at all events, it was to provide funds for the better

endowment of the clergy, schools, and hospitals, but while the

Presbyterian party saw in it a design to increase the power of the

Prelacy, it had the further effect of estranging a number of the great

families who had been granted ecclesiastical lands or churches, and had

no intention of parting from them without a struggle. Sir James Balfour

calls it that revocation which "was the ground stone of all the mischief

that followed after, both to this king's government and family."

I must here introduce;

another name in my story, that of John Stuart, Earl of Traquair, with

whose fortunes Sir Patrick of Elibank and his son and successor were

closely connected. Traquair was throughout, for good or evil, an ardent

supporter of the Royal cause. he was descended in the female line from

James II. of Scotland, and again directly from Joan, the Queen Dowager

of James I., who, as granddaughter of John of Gaunt, was of the Royal

line of England, and thus Traquair could claim the Royal blood of both

kingdoms. Aristocratic, and without sympathy for those whose views

differed from his own, he was little fitted as an instrument to carry

out schemes which met with vehement protest, except by the application

of force, which was difficult in the face of a united opposition.

"I sal either mak the

service be read heir in Edinburgh or I sal perishe by the way. Nothing

proves more prejudicial! to your Maties- service than to prosecute yr

commandments in a half or halting way "—thus he wrote to the King; and

again, " From which sect (the Presbyterians) I have seldom found any

motioun proceid but such as did smell of sedition and mutiny."

Holding such views it

is little likely that he would succeed in persuading a proud and

obstinate people to adopt a course they abhorred.

The connection between

Traquair and Sir Patrick Murray may have originated in the fact that he

succeeded Sir Gideon as Treasurer Depute (with, I think, one

intermediate holder); at all events, they were officially of the same

view and privately on intimate terms, which were cemented by the

marriage of Sir Patrick's eldest son with his daughter Elizabeth Stuart

in The history of Scotland at this period was decided in the Cabinet of

the English Primate, and in Traquair, Laud found a willing instrument,

and Murray became involved by the acts of his friend.

In 1013 Sir Patrick was

raised to the Peerage of Scotland as Lord Elibank, in consideration of

his " worth, prudence, and sufficiency, and of the many worthy services

done to His Majesty, our late dearest Father in his Council, Session and

Exchequer by the late Sir Gideon Murray." The patent was issued from

Oxford, where the king then maintained his government. Sir Patrick had,

indeed, devoted himself and his goods to the Royal cause, and had raised

a troop of horse which accompanied the Scots convoy sent to Oxford in

this year. In 1647 he was one of the six Peers of Scotland who opposed

the decision to hand over the person of King Charles to the English

Parliament, and in the final step, when the next year Scotland attempted

to retrieve her lost honour, Traquair, who had staked his all, was

followed by Lord Elibank, who became deeply involved. The family papers

give some insight into the extent that the estates were burdened, and it

appears probable that the voluntary contributions to the Royal cause

were supplemented by voluntary levies enforced by the Covenanters, for

the principal estate of Ballencrief, being situated in the midst of

country which was the cockpit of the opposing forces, was naturally

placed under contribution by the "War Committee" of the Scots Estates.

Lord Elibank did not

long survive his royal master. He died in 1650, almost within sound of

the long drawn-out conflict at Dunbar, which proclaimed the end of

Scotland as an independent power. More fortunate than Traquair, who

lived to see his estates pass into other hands, and who died in

penury—of starvation, it is said—the final crash came after his death,

and it was the lot of his eldest son, Patrick, now second lord, to sec

it decreed that the family property should pass into the hands of his

creditors. This was in j 058, and little more than two years later the

second Lord Elibank died. There is nothing on record to give details of

his life. lie was but forty when he died, but it is not difficult to

imagine that the son-in-law of Traquair, ruined by the ruin of the Royal

cause, would meet with little sympathy in the country under the iron

heel of Cromwell and dominated for the moment by the triumphant

Covenant.

The third lord, also

Patrick, was a lad of twelve years of age when he succeeded to the

family honours. It appears from the reeords that the breaking up of the

estates had been avoided by a family arrangement. A statement exists

whieh shows that they continued in possession, but with a mortgage of

85,400 merks, the advent (interest) on which, together with the

necessary outgoings, absorbed two-thirds of the revenue and left but a

slender income to the noble owner. His education was finished at

Edinburgh in 1666, not, we may be certain, on a luxurious scale, for a

receipt exists for "the sum of 35 pounds Scots for a high Chamber in the

College possessed by my Lord Elibank and his servants from Michaelmas,

1664, to Michaelmas, 1666." That is an annual rent of about thirty

shillings sterling!

Lord Elibank married in

1674 the daughter of Archbishop Burnet, and left one son, Alexander, who

succeeded, aged nine, to the title, and was the father of General James

Murray, the subject of this memoir.

An inventory of the

"goods, geir, and plenishings" of the house at Ballencrief exists, taken

by the "tutors" of the minor, which give a good idea of the home in

which my hero was born some thirty-four years later. In the great hall

and dining-room, besides many hangings of arras, some described as

"pictured." used no doubt to cover the bareness of unplastered walls,

were three carpets, twenty two "Rushie leather chairs and one resting

chair," a clock in a "fir case." The "Lady's Chamber and a little dark

room off the same" contained a good equipment; the "Chamber above the

dining-room" had, among other things, a "fashionable bedstead" and a

"looking-glass." There were also the "Dames Chamber," "Maiden-head

Chamber," and the "Picture Chamber," the last containing, inter alia, "a

chest full of old accompts and papers belonging to the deceased Sir

Gideon, most theieof anent the Treasury"; here were also four pictures.

My lord's closet contained four guns, and my lady's a "posseline cup set

in gilded silver," also two looking-glasses. The linen closet was no

doubt the pride of its owner, it contained what must have been an

unusually good equipment, 19 pairs of sheets, 13 tablecloths, 6 dozen

and 4 napkins, etc., etc., and "ane English blanket"! Judged by the

standard of the time, such a mansion must be classed as well found, the

possession of three carpets in the Great Hall was an uncommon luxury,

for Graham, in his interesting work on Social Life in Scotland, tells

that more than fifty years later not more than two carpets existed in

the whole town of Jedburgh. There was evidence of refinement, too. What

would not a collector give to-day for the "posseline cup set in gilded

silver"; genuine of at least the Kang He period and probably much older!

Young Alexander

completed his education at the college at Edinburgh, and an important

result of his college career was that the young lord fell in love, and

married, aged twenty, Miss Elizabeth Stirling, the daughter of an

eminent surgeon of Edinburgh, and afterwards a member of the Scots

Parliament. The young lady at an early age displayed the possession of

independent character, which sometimes led her into eccentricities, and

she transmitted to her family more than a usual share of those traits

which impel men to keep clear of the well-worn grooves of life, and to

strike out lines of their own. John Ramsay, in his Scotland and

Scotsmen, relates an anecdote which shows that Miss Betty possessed a

masterful character. An incautious minister, when undertaking "public

examinations," addressed her as "Betty Stirling," and drew down on

himself a scathing rebuke from the young lady, who stated, not without

adjectives, that " Mistress Betty," or "Miss Betty" was the style of

address she was accustomed to, but certainly not " bare Betty "—and as

Bare Betty she was generally known afterwards. But this side of her was

not the best; she was a tender-hearted mother and adored by her somewhat

unruly family. In 1739, then a widow, she wrote to her eldest son, under

orders to join Lord Cathcart's expedition to the West Indies, "If ye

have any comfort to give me for God's sak writ soon, for I'm in the

utmost distress : oh, thes wars will brack my heart"; and, again, her

son George, writing to his brother shortly after the battle of Quebec,

"I wish our good mother had lived to a been witness of the praises so

deservedly bestowed on you."

Reading between the

lines of the letters it is not hard to see that the difficult task of

keeping the family above water in times of great financial stress was in

her capable hands. And when in 1720, a year when all England went crazy

with the speculative mania, of which the most remarkable episode was the

great financial catastrophe known as the South Sea Bubble, Lord Elibank

lost heavily, we may be sure that his lady had an addition to her

anxieties which must have tried her to the utmost. The sequel is best

told in a letter to Lady Elibank a few weeks later.

"I am infinitely more

vexed that you should torment yourself so much, which I assure you is

more galling to me than any misfortune that has yet befallen me . . . as

I shall answer God I have never bought a farthing's worth of stock but

that third subscription, nor you may depend on it will I venture a groat

more that way, for now the South Sea has fallen to its primitive this

day, so that it seems now past all recovery ; what parliament will be

able to do with it I cannot tell."

Lord Elibank was a

heavy loser; he returned to Scotland to face the situation. In 1723 he

was one of the founders of the "Society of Improvers" in the knowledge

of Agriculture in Scotland, of which it is stated in the Life and

Writings of Lord Kawes, "Before it commenced we seemed to be several

centuries behind our neighbours in England, now I hope we are within

less than one of what they arc either with regard to husbandry or

manufacture." To-day the Scots farmer is accounted the best in Great

Britain.

To Alexander Lord

Elibank and his wife was born a numerous family of fifteen sons and

daughters, of which five sons and six daughters survived them. And as

these brothers of my hero reappear in this story, it is convenient that

I should here briefly indicate their history, the more so that, as will

be seen, their action had a very marked influence on James Murray's

fortunes.

The eldest son,

Patrick, afterwards fifth baron, was at first in the military service,

and it is a curious illustration of the strange regulations of the day,

to find his " commission " as captain of a company in Colonel Alexander

Grant's regiment, signed by Queen Anne in 1700. The gallant captain

being then just three years old ! Not less strange is it to find in 1711

two records relating to the name officer, the one a bill for his board

while at school in Edinburgh, and the other a statement of his

regimental pay, including "Flanders Arrears" for himself and three

servants. The recipient being then aged eight.

Soldiering, though he

subsequently saw a good deal of service, was not the line to which his

inclinations bent him, and a few years after his marriage with the widow

of Lord North and Grey in 1735, he left the army and followed that

literary career which was more to his taste.

"Nothing was wanting to

make him an admired writer but application and ambition ' to excel,'"

writes John Ramsay. " For a number of years Lord Elibank, Lord Karnes,

and Mr. David Hume were considered as a literary triumvirate, from whose

judgment in matters of taste and composition there was no appeal. At his

house the youthful aspirant to fame saw the best company in the kingdom,

and drank deep of liberality and sentiment. . . . During the reign of

King George II. Lord Elibank kept aloof, being a professed Tory if not a

Jacobite in his talk."

Lord Elibank was a

founder of the Select Society of Edinburgh, which included among its

members the most brilliant wits in Scotland. He was said to have the

"talent of supporting his tenets by an inexhaustible fund of humour and

argument," and Dr. Johnson, who paid a visit to Ballencrief in 1773, put

on record his opinion that Lord Elibank was "one of the few Scotchmen

whom he met with pleasure and parted from with regret," and the learned

doctor was not as a rule complimentary, certainly not to Scots As a

member of the famous Cocoa Tree Club, at which it was said the coach of

a Jacobite invariably stopped of its own accord, Lord Elibank gave some

ground for Horace Walpole's opinion that he was a "very prating and

impertinent Jacobite!"

George Murray, the

second son, entered the Navy in 1721, and, after seeing service during

the war of 1740 in the West Indies, accompanied Lord Anson (then

Commodore) in his famous voyage round the world, but a full share of the

perils and successes of that expedition was denied to him, as his was

one of the two vessels disabled during the great storms which were met

with when rounding Cape Horn. In 1744, in command of the Revenge, he was

present at the naval action off Toulon, and in 1750 he retired as a

rear-admiral. His impatient character unfitted him for a successful

career in the service. He succeeded to the Barony of Elibank on the

death of his brother, and died in 1785, leaving no male heirs.

Gideon, the third son,

entered Holy Orders from Oxford in 1733, and even in this profession he

had some of the warlike experiences of his brothers, having served as

chaplain to the Earl of Stair during the operations in Germany in 1743.

After filling several posts of importance in the Church, he was finally

appointed to the rich canonry of Durham. It is said that jhis chance of

a bishopric was lost on account of the part taken in politics by his

brothers. Alexander, the fourth son, was the enfant terrible of the

*He married Lady

Isabella Mackenzie; And, afterwards Duchess of Sutherland, descended

from this union. The forfeited Earldom of Cromartie was revived in her

person family, and whatever judgment may be passed on his actions, it

must be at least admitted that he displayed strong independence of

character, the results of whieh unfortunately reacted adversely on the

more law-abiding members of his family at a period when the House of

Brunswick, with every desire to deal moderately with the adherents of

the Stuarts, could not afford to pass over such open antagonism as was

displayed by him. Horace Walpole, in 1737 (Journal of Geo. II. 1 wrote

of him and his brother (Patrick, Lord Elibank) that they were " both

such active Jacobitcs that if the Pretender had succeeded they would

have produced many witnesses to testify their zeal for him."

Walpole was, perhaps,

not an impartial witness, but unquestionably Alexander Murray made

himself an object for the resentment and persecution of the Whig

ministers, and by a strange irony of fate the popular cry of " Murray

and Liberty," which was raised by the mob on more than one scene of

tumult, was separated by but a short interval of time from that of

Wilkes and Liberty," which the same mob used to greet the man who set

himself to be the bitter enemy of all the Murrays, and whose trenchant

and powerful pen did much to hinder their success. After a period of

imprisonment in Newgate, by order of the House of Commons, it was

resolved to bring Murray to the bar of the House, there to receive

admonition on his knees ; but on the Speaker requesting him to kneel, he

replied, "Sir, I beg to be excused; I never kneel but to God." It was

thereupon resolved that he was guilty of a high and most dangerous

contempt of the authority of the Commons and was recommitted to Newgate.

After the prorogation of Parliament he was released by the sheriffs of

London, and went in triumphal progress to Lord Elibank's house in

Henrietta Street. Murray became a popular hero, and the political

pamphleteers and verse makers were busy in exciting the passions of the

people.

Before Parliament met

again in November, 1751, Murray had gone to France, and while there was

much in evidence at the Court of Prince James Stuart, from whom it is

said he received a patent as Earl of Westminster—at all events, he was

known later as Count Murray, and finally received letters of recall

under the Privy Seal, dated 1771.

The fifth and youngest

son was James Murray, the subject of this memoir. He was born at

Ballencrief on January 21, 1721, old style. The time of his advent was

not a convenient one, coming as it did immediately after the South Sea

smash, and though I have only negative evidence to go on, the almost

complete absence of mention in the letters of the family tends to

indicate that young James was not very warmly welcomed, and it is pretty

certain that he shared in few of the advantages which Lord Elibank did

his utmost to bestow on his other sons. It is probable that his early

youth was not a very happy one, and at least the impoverished condition

of the estate at this time permitted few luxuries for the fourteenth

child ! As to luxury, however, it is difficult for us of the twentieth

century to form a conception of the conditions of life in Scotland in

the early years of the eighteenth century. Since to the Scot born and

bred in these surroundings the conditions presented nothing abnormal,

and gave to one ignorant of anything better no cause for complaint,

there would be no point in referring to them here, were it not that in

the preceding pages I have endeavoured, by sketching the ancestry and

immediate relatives of my hero, to give some insight into the

characteristics with which he was likely to start the battle of life. So

by a brief sketch of the surroundings of his youth I would emphasise the

reason why so many young Scots, when carving for themselves names which

adorn the history of the Empire, commenced their career with that

contempt of hardship, or, if you prefer it, that ignorance of luxury,

which formed the best possible equipment for the pioneer and for the

soldier.

It is true that in

England the amenities of life were very far behind our standard, but

Scotland was very far behind England in everything that connotes

comfort.

The country was

miserably poor. Measured by English standards, a "rich" man in Scotland

lived from hand to mouth, in the most literal sense. Dependent almost

entirely on the fruits of agriculture, carried on by the most obsolete

methods, the landlord and his dependents were always at the mercy of the

season. What would be thought of a noble lord in England -who, so late

as 1728, wrote, "Nothing but want of wind in the barn doors these two or

three days by gone hath hindered the barley coming to you"? and though

Henry Fletcher of Saltoun, the friend and neighbour of Lord Elibank, had

brought over the invention of barley mills and fans from Holland, this

method had evidently not been taken up at Ballencrief.

Even had the methods of

agriculture enabled crops in proper proportion to the land cultivated to

be garnered, they would have been of little use, for the means to carry

them were wanting. "There was no such convenience as a waggon in the

country," says Tobias Smollett, when he started under the pseudonym of

Roderick Random to seek his fortune in England, nor, had they existed,

were there any roads on which they could travel. Produce, baggage, even

coals were carried in small quantities at a time on horse-back, and

travellers of all degrees were obliged to ride or be carried in chairs.

A fifteen-year-old lad of to-day would think himself asked to undertake

a big thing if obliged to write, as young Gideon Murray did in 1726, to

his father, ..." If you please you may send horses for me on Saturday,

one for myself and another for my trunk and eloathes." To be whirled

home for the holidays by express train and motor is a different affair

altogether to facing a twenty-mile ride on execrable roads none too well

secured from attack by thieves.

The difference of

nearly two hundred years has, however, altered the schoolboy very little

in one respect, and I cannot forbear quoting again from the same letter.

"My lord, you cannot

expect but that I may be in some little debt now in this time of year,

when the bowls and other such diversions are in hand. Half-a-crown or

three shillings or anything will serve my turn. . . . I pray you don't

forget ye money with ye first occasion!"

However, as I have

said, the comparison as to luxury of travel or other things is not fair.

The young Scot was used to it, and "use is everything," as was said on

another occasion; but the training had its advantages, and started the

youth of that period with a self-reliance and power of command which the

young gentleman of to-day has not got, and perhaps requires in less

degree. The astonishing age at which men succeeded to high places in

those (lays may have been due to this early training. Can any one

suppose that the younger Pitt would have been a prime minister at

twenty-five if he had lived a century and a half later, or Napoleon an

emperor at thirty-five if he had been born in the nineteenth century ?

Wolfe was but thirty-two at Quebec, and our James Murray was governor of

a province and commander of an army at thirty-nine. Wellington was but

thirty-four at the close of the Mahratta War. It was the century of

young men!

If the circumstances of

the landowner in Scotland were bad, those of the peasantry were

infinitely worse. Even Andrew Fletcher, the apostle of liberty, was

forced to advocate serfdom as the best means of ensuring that a large

number of the population should not want for the necessaries of life.

Within a few miles of Ballencrief the labourers in the salt and coal

mines were in fact slaves, and in his boyhood James Murray must have

been well used to witness scenes of horrible misery, which cannot but

have left an indelible picture in his mind. To this we may, with some

certainty, trace the firmness with which he subsequently, to his own

personal detriment, protected the French Canadians from oppression.

Thus the daily life and

the daily scenes tended to form the character and produce that stern

gravity which in boyhood, as in manhood, left its stamp on the Scot.

Hardship, even danger, was the common experience of all; pride, poverty,

and self-reliance were the hall marks by which the pupils of the school

might be recognised.

I have described the

ancestry of James Murray, and I have said something about the conditions

which formed his experience; am I wrong if to both these factors I

attribute the successes and the failures which were his lot ? That he

was generous and high-minded we shall have ample evidence. Gifted with a

wide and statesmanlike insight of his opportunities and his

responsibilities, where he built he laid solid foundations, and did not

desire to run up a gaudy structure that might have won for him greater

reward from short-sighted governments incapable of appreciating work by

its durability. He followed his ideal consistently, looking neither to

the right hand nor the left, and perhaps too indifferent to the

obstacles which stood in his way to pay enough heed to the manner in

which he removed them. The "national prerogative" of pride he possessed

is well illustrated by his writing to the Due de Crillon, that he had

attempted to assassinate the character "of a man whose birth is as

illustrious as your own."

Possibly he carried

this "prerogative" to excess, and was somewhat autocratic, and it may be

intolerant, with his subordinates, yet to the rank and file and to the

people whose government was in his hands he was lenient, approachable,

and beloved. No general could have got out of his troops more than he

did. "Old Minorca," as they christened him afterwards, was a soldier's

general. If on suspicion of incapacity or neglect he acted strongly,

perhaps harshly, yet my history will show that the occasion demanded

promptness and vigour, and Murray was no respecter of persons. To those

who showed devotion to duty, no man was more ready to award praise and

recommendation, nor did failure meet with his condemnation if honest

endeavour accompanied it. "A man of the most ardent and intrepid

courage, passionately desirous of glory, if he was ever ready to admire

bravery in others, and there was no hardship and no adventure which he

was not ready to share when his duty permitted him. His equally generous

and intrepid leader, Wolfe, wrote of him after the capture of Louisburg,

"Murray has acted with infinite spirit. The public is indebted to him

for great service." *He was modest withal, and displayed no desire to

figure in public, which was perhaps uncommon at the time. When the

painter West approached him to allow his portrait to be included in his

picture, "The Death of Wolfe," he refused, saying, I was not

there, 1 was commanding the troops in my charge."

It is characteristics

such as these that it is my duty to portray, and the measure of my

readers' approval will be the degree of my success.

Of the boyhood of James

Murray there is, as I have already said, but little record. His

education apparently commenced at Haddington, but in January, 1734, he

was a pupil at the school of Mr. William Dyce in Selkirk, where he

remained until August, 1736. His holidays, it appears, were spent partly

at Ballencrief and partly at Westerhall, with his sister Barbara (Lady

Johnston), and, indeed, it appears that both she and her husband took a

warm interest in the lad, for there is an entry in the school account

showing that his "pension" (pocket money) was increased from 3d. to 6d.

a week "by Sir Jas. Johnston's orders."

It was during his

residence at Selkirk that his father died in 1735, when the young

scholar was but fourteen years old, and we may be sure that this event

added to the difficulties which he had to face in making his start in

life. It is a family tradition, for which I can find no definite

confirmation, that the lad was destined for the Law— possibly this was

his father's intention, for he had already given two sons to the Army,

one to the Navy, and one to His brother George, writing in after years,

says, "You cannot think how much the folks in Haddington value

themselves for your being, as they pretend (claim), educated there." the

Church, but his early death, combined with the inclinations of the lad

himself, caused a change in this plan.

Among the visitors to

Ballcncricf was Colonel William Murray, who had made for himself a

distinguished career in the Dutch Service, in that famous fighting force

known as the Scots Brigade. Like Uncle "Toby" Shandy, William Murray had

been a hero at the Siege of Namur, where he was promoted for his

service, and like him, too, there is little room to doubt that he was

full of stories of the "Barrier Towns "—of sieges, assaults, and forlorn

hopes—which young James drank in with avidity. It is probably due to the

tales of this veteran of the wars in the Low Country, who ended his

career with the resounding title of "Sergeant-Major-General of

Infantry," that James imbibed that strong taste for arms which decided

his choice of a profession. He was not without influence to attain his

desire, for his brother Patrick had married in 1735 the widow of Lord

North and Grey, a lady of Dutch extraction, daughter of Cornelius de

Yonge, Receiver-General of the States of the United Provinces, Whether

the tradition, that James took the law into his own hands and "enlisted"

in the Scots-Dutch, is true, or whether, and I think this is more

probable, his family influence procured for him a more legitimate method

of beginning his career as a soldier, cannot now be said with certainty;

but at all events he became a "cadet" in the 3rd Scots Regiment, then

stationed at Ypres in West Flanders, on December 6, 1736. It was in this

regiment that his cousin, William Murray, had served, and in it was also

serving a Major Boyd, who had been known to his father and whose name

appears more than once in the letters.

This event took place

during what was known as the "Period of Peace," when after years of

continuous war the brigade had nothing more exciting on hand than

garrisoning the frontier towns and a constant readiness to repel French

aggression. But although the times were peaceful, no better training

ground for a young soldier could be found- The corps which had fought

throughout

Marlborough's wars, on

whose colours the laurels of Ramillies and Malplaquet were still fresh,

and which maintained a pride of discipline and place which not

infrcquently led to disputes as to precedence with other troops in the

allied armies, was, we may be sure, a good school. The three years which

James Murray passed in these circumstances must necessarily have been

years of soldierly education, in which the cadet, while still retaining

a species of commissioned rank, yet performed all the duties of a

soldier in the ranks, a circumstance which our hero used to allude to in

later years, laughingly saying "he had served in all ranks except that

of drummer." Nevertheless, the prospect at the moment in the Dutch

Service was not one to commend itself to an ambitious aspirant to

military fame. Promotion was slow, and no doubt to those soldiers of

fortune serving in a foreign legion the principal causes which ensured

their sympathy, namely, plenty of fighting, quick promotion, and if

fortune favoured, a share in the spoil of war, were for the time being

wanting. Thus it came about, when England plunged hot headed and all

unprepared into war with Spain, that not a few of the younger officers

serving in foreign corps sought commissions in the regiments about to be

raised in England, and among them was James Murray, who, apparently from

his brother's influence, was offered a second-lieutenancy in the English

army.

Thus it was in the year

1740 that Murray, then nineteen years old, received his first commission

from George II., and commenced his military career under the Union Flag

at the beginning of a period which offered opportunities which surely

were unequalled by any other in English history. |