|

In the last chapter we

have carried the story to the commencement of De Levis' long-threatened

advance ; once again hostile armies were moving on the Plains of

Abraham.

Let us consider the state of the garrison before reviewing the steps

taken by Murray to meet this new danger. Wc know that at an early date

after the capture of Quebec the garrison, excluding officers, sergeants,

and drummers, consisted of 1873 men fit for duty, besides 1376 who were

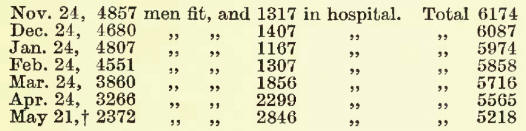

sick or wounded. In successive months these figures varied as follows :

Figures which arc

eloquent enough of the constant drain on the available fighting force.

In March 166 men had died from disease, in April the number was 119. The

total number of deaths from disease up to the end of April was over 700.

There were, besides men discharged as unfit, desertions, and losses from

action, nearly 100 more (excluding the battle of April 28).

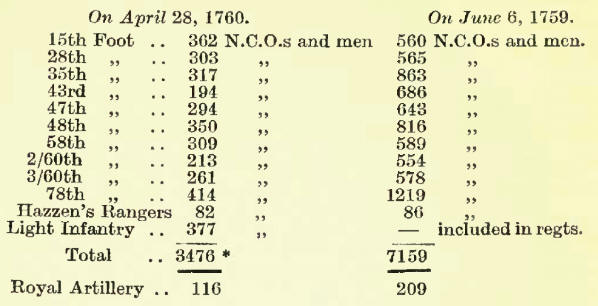

Of the total effective strength Knox states that 3140 only were

available for action outside the town. Murray, in his despatch to the

minister, giv es the strength n round figures as 3000 ; but he details

the actual marching-out strength on April 28 as follows, and, to show

the great reductions, I have inserted the figures of the embarkation

returns when the force started for Quebec in the previous year:

Thus the battalions

were less than half their original strength. The Highlanders hardly

one-third, for they had suffered severely both in action and from

sickness, the latter probably due to their unsuitable clothing. The

43rd, too, were almost non-existent—"the unhealthiest corps in the

garrison," Knox describes them; nor can it be doubted that many men,

though classed as "fit," were in reality only convalescent, and were not

in a condition to undergo the fatigues of an exhausting march over

country in the worst possible condition.

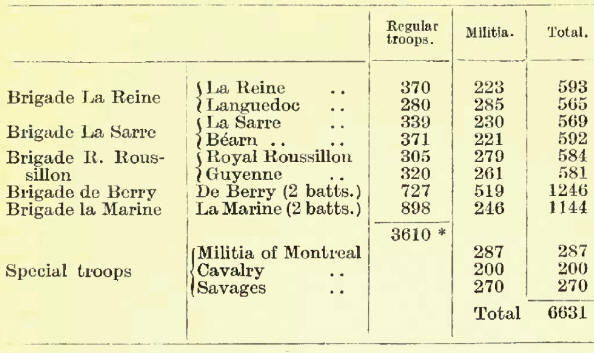

It will be convenient here to review the forces that De Levis was able

to bring into the field. All the eight battalions of French regular

troops—thai is, the whole available force in the colony—had been

assembled (the Regiment La Reine, and the two battalions of the Regiment

de Rerry, had been added to the five which had formed Montcalm's force

in the preceding year). The two battalions of marine troops were also

present, and all ten

battalions had been strengthened by the inclusion of detachments of

militia, winch brought them up to the strength below (Journal de Levis):

a letter dated May 10 to Amherst, estimated the number of the enemy at

10,000. Knox gives a still larger figure, but admits that he thinks the

return on which he relied was exaggerated (Knox's Journal). Taking into

consideration the figures tolerably well known of the strengths of the

French regular battalions at the time of the siege of Quebec, I think

Murray over-estimated,* and that De Levis' statement is trustworthy.

As 1 said before, statements have been made that Murray was hot-headed

and impetuous, inclined to underrate the offensive power of his

opponents. In his Journal, and in the measures he took, there is surely

nothing to give colour to such an opinion. On the contrary, with the

action taken by both sides now clearly before us, it is impossible to

come to any other conclusion than that the preliminary measures which

were taken were wise and soldierlike ; and far from underrating his

enemy, he makes it clear that his object in the various steps he took

was to delay a progress which, from the known strength of the French and

his own equally well-known weakness, he saw was inevitable, particularly

as the French had the command of the water-way. His object in occupying

Cap Rouge, for instance, was " to hinder the enemy from landing their

cannon in the river, and (to) oblige them to bring it round by land,

which, considering the badness of the road, would in that case delay the

operations a considerable time " (Murray's Journal, April 17). At the

same time, he had taken every possible step to expedite the appearance

of Lord Colville's squadron in the river, recognising that while they

remained masters of the river the French had an advantage of the most

momentous importance.

It is proper to repeat here that the removal of practically the whole of

the English fleet was a mistake of the gravest nature. If the French

ships could winter in the Sorel River, and if the Racehorse (8 guns) and

Porcupine (14 guns) sloops, besides three smaller sloops, could winter

at Quebec, there seems no possible reason why a force sufficiently large

to counter the French frigates should not have remained also. Had this

been the ease this battle of the plains would most probably never have

been fought.

Murray recognised most clearly that De Levis woidd bring his force down

to St. Augustin by water, that in face of opposition there, and with the

bridges broken down, he would be obliged to pass inland and cross the

Cap Rouge River higher up, debouching at Lorette and attacking at Ste.

Foy, hence the post of Ste. Foy was held in force.

As an aid to a second line of defence he saw the advantage of a redoubt

some 1500 yards from the walls of the town commanding the almost level

ground of the Plains of Abraham. This redoubt was about 160 yards to the

east of the present racecourse, and 100 yards south of the Sillery road,

and was of great assistance during the subsequent battle, as will be

seen.

His third and principal defence was to be a fortified line covering the

ridge of high ground known as the Buttes-a-Neveu, about 800 yards

outside the walls, the axis of which is roughly parallel to the trace,

and formed an exceedingly important position dominating the town

defences by its considerable height, commanding also the ground over

which a hostile force must approach.

A fourth line, intended to remedy the defective trace of the

fortification, was a line of six blockhouses built outside the walls at

distances varying from 50 to 250 yards.

It was on April 17 that Murray records in his Journal:

"The best intelligence was now procured that the French had armed six

ships which had remained in the river last autumn, with two gallies

which they had built; that they designed to bring down this squadron

with a number of boats to transport the troops to Cap Rouge."

De Levis records in his Journal that on this same date he sent M. de la

Pause, "Aide Marshal-General des Logis," to prepare Jacques Cartier for

the disembarkation. On the 20th the whole army moved, and pushing

forward in spite of great difficulties from floating ice, arrived at

Pointe-aux Trembles on the 25th and 26th (April).

Murray continued work on his post at Cap Rouge and on his advanced

redoubt, but he found the utmost difficulty on account of the state of

the men. "As the garrison was so sickly," he says, "I was obliged to use

them with the utmost tenderness." At this time he ordered all the people

out of the town, "that I might not be obliged to watch within as well as

without." Two pieces of cannon were drawn "with infinite labour and

trouble to St. Foix." Knox tells us that the roads being impassable for

horses by reason of the dissolving snow, these guns were dragged by the

men.

The advantage of Murray's dispositions were summed up very clearly by De

Levis in his Journal:

"1 (Vcnnemi) comptoit defendre tous les passages depuis le Cap Rouge

jusqu'a Quebec dont Vespece est de trois lieues ; il ne parut pas

possible de tenter de passer au has de la dite riviere suivant le grand

chemin de Montreal a Quebec, ni de tenter de faire un debarquement

depuis le Cap Rouge jusqu'a Quebec ; il fut resolu qu'on chercheroit a

se rendre maitre des hauteurs en passant dans Vinterieur des terres,

traversanl la Riviere de Cap Rouge a deux lieues au dessus de son

embouchure, passant par la vieille Lorette et traversant les Marais de

la riviere de la Suette pour s'emparer des hauteurs de Sainte Foi et

gagner le susdit grand chemin."

Thus necessitating a big detour over a very bad road ard making a

frontal attack over marshy, low-lying country, over which the troops

could only advance on a narrow front against the said " hauteurs de

Sainte Foi." The nature of the land below the present village of Sainte

Foi has vastly changed from what it was at the time with which we are

dealing. Drainage and cultivation have converted it into fields and

grazing grounds, and almost extinguished the little river Suette, which,

indeed, is hardly known to the inhabitants of to-day, but in those days

it was described thus:

" ha riviire Suete . . . tombe dans la plaine qui separe

Lorette de Sainte Foy a environ deux milles a I'ouest de Veglise de

I'ancienne Lorette, y fait mille et mille de tours, traverse le chemin

de la Suete, puis gagne Vest directement jusqu'd son arrivee dans la

petite riviere Saint Charles a, deux milles environ au Sud-est de

Veglise (de Sainte Foy) " (Bulletin des Recherches Historiques).

On the 26th De Levis and his army embarked at Pointe-aux-Trernbles and

came by water to St. Augustin, opposite to Cap Rouge on the other side

of the river of that name. On this date De Bourlamaque, who had been

sent forward at once to reconnoitre and to construct bridges at the

selected point over the Cap Rouge, sent back word to De Levis at two

o'clock that a passage was possible. The arxny advanced at once and

before nightfall a brigade had occupied Lorette. The night passed by the

French army is thus described by De Levis:

"II fit une nuit des plus affreuses, un orage et un froid terribles, ce

qui fit beaucoup suffrir Varmee qui ne put finir de passer que bien

avant dans la nuit. Les ponts s'etant rompus les soldats passoieni dans

Veau. Les ouvriers avoient peine a les reparer dans Vobscurite, et, sans

les eclairs on eut ete force de s'arreter."

Three pieces of artillery only could be landed, and these could not be

carried across the river until the next day.

As mentioned at the end of the last chapter, a good deal has been made

of this to show that Murray had been caught napping. I do not think this

is justified ; had he known every detail of De Levis' movements he could

hardly have acted otherwise than he did, and we know of his desire to

encamp his force at Ste. Foy had the state of the men permitted it. Two

hundred men had been put on the sick list during the week, and he dared

not risk it. The great storm of the 26th-27th would probably have been

fatal had he risked it. In his Journal De Levis tells us that De

Bourlamaque, with the advanced guard, had been sent forward across the

Suete Marsh, and had taken post in some houses below Ste. Foy. It would

seem probable, therefore, that the outpost knew of the presence of the

enemy, though Murray does not mention the fact. Knox, however, records

on the 21st, that " the French begin to appear numerous in the vicinity

of Cap Rouge and Lorette," and it is certainly the case that the whole

garrison was on the alert.

There can be no doubt that De Levis had performed a military operation

which deserves the highest encouragement. Not only had every detail of

the disposition of the troops and of the incorporation of the militia in

the cadres of the regular units been thoroughly thought out and embodied

in clear and precise orders, which are quoted in his Journal,* but,

starting on the 20th of the month, he had in seven days, partly by land

and partly by water, conveyed a large force through bitter weather and

incredible difficulties a distance of quite 150 miles. It is true that

some part of the force were cantoned at Jacques Cartier, and it is true

that the men had spent a winter in surroundings to which they were

accustomed, and were probably fit to face hardships; but, having all the

circumstances in consideration, and the difficulty experienced in

obtaining military supplies, of which the French were very short, this

march of Ihe Levis should be remembered as an e xample of what a brave

and resolute commander can accomplish.

Immediately on receiving the news that De Levis was at Lorette, Murray

marched out with the Grenadiers, picquets, and Amhersts, and two field

pieces—perhaps 500 men in all. Three other regiments, commanded by

Colonel Walsh (probably 28th, 47th, and 58tli, about 700 men), were to

march out to support this advanced body (Knox refers to ten field pieces

as having been taken— possibly the remainder were with the supporting

body). The 35th Regiment, under Major Morris, was sent forward to

Sillery to support the outpost at Cap Rouge.

Of these I will quote part of one only: "La force d'infanierie consiste

dans la discipline et I'wrdre. Messieurs les commandants des corps et

officiers en general doivent dormer leurs attentions et applications

pour mettre en vigueur ces deux points, malheureusement irop neglig^-s

dans nos troupes."

It was ten o'clock before De Levis was able to move. He bad been obliged

to defer any attack, on account of the plight of his troops, following

on the hardships of the preceding night. This gave Murray ample lime to

bring up lus reinforcements to Ste. Foy, and, as De Levis tells us, they

opened a lively fire on any of his (De Levis') troops that showed

themselves outside the woods that patched the low ground in several

places. De Levis describes the situation very succinctly:

"Ayant vu les ennemis se renforcer, ne pouvant ju-ger de leur nombre et

en paroissant oeeuper les endroits aceessibles et la colline ou ils

ctoient . . . comme d'ailleurs, I'eglise de Sainte-Foi qui etoit

fortifiee avec du canon e'tant en face du chemin ou nous etions, il

falloit les forcer dans cette eglise et dans les maisons voisines, qui

se flanquoient, et que nous ne pouvions mener Vartillerie que par le

chemin qui n'etoit pas practicable, ni deboucher qu'a travers des bois

mare-cageux et nous former apres les avoir passes que sous le feu de

leur artillerie at mousqueterie, tout cela Jit prendre la resolution a

M. le Chevalier de Levis, vu le mauvais etat ou avoit etc Varmee depuis

trente heures, d'attendre a Ventree de la nuit a se mettre en marche

pour aller les tourner sur leur gauche."

Murray records that he found the enemy

"in possession of all the woods from Lorette to St. Foix and just

entering the plain. However, they declined to attack me in the

advantageous position I had taken; but, finding their numbers

increasing, and endeavouring to get round me by the woods, the weather

very bad, and having received intelligence while 1 was out of a report

that two French ships were at the Traverse (i.e. the east end of the

Isle of Orleans), I thought it proper to retreat to the tow."

The church at Ste. Foy was blown up,* as there was no means of removing

the ammunition, etc., stored there. De Levis records that this took

place at about one o'clock, and that on seeing Sainte Roy abandoned he

ordered his cavalry and advanced guard to occupy the ground.

An interesting little side-light on Murray's character was told me by

the Abb£ Scott, cure of the parish of Ste. Foy, that after the

withdrawal of We Levis, Murray sent £25 as a contribution to restoring

the church. This incident is recorded in the church records.

Thus ended the first phase of the battle, which was indeed merely a

reconnaissance. Murray certainly relinquished a strong position, and it

seems barely possible that De Levis would have succeeded in making a

night march with his weary troops over marshy stream-intersected ground,

so as to make an attack between Ste. Foy and Cap Rouge. Almost certainly

he could not have conveyed his artillery. The retirement gave his men a

much-needed rest and a sense of victory, almost equally important. In

normal circumstances it can hardly be disputed that Murray should have

held on to Ste. Foy and brought up his reserves to cover the two miles

of distance between his left and Cap Rouge. But the circumstances were

not normal. The number of men he could dispose of was a maximum of

3000—he estimated the enemy at 10,000. We believe this estimate was

excessive, but, at least, he was outnumbered by more than two to one.

But probably the deciding factor was the condition of his troops. The

march of some five miles in the snow-wreathed roads, the several hours

of facing the enemy, had exhausted many of his sickly soldiers. The day

was cold and wet; another night such as the one just passed would have

the worst possible effect. A defeat at or near Ste. Foy would almost

certainly result in complete disaster. He thought it " proper " to

retire ; lie was probably right.

In the night we may suppose there were anxious councils. As for the

troops, Knox draws a brief picture, which is eloquent enough:

"The army, being extremely harassed and wet with constant soaking rain,

were allowed an extraordinary gill of rum per man; and some old houses

at St. Rocque were pulled down to provide them with firewood in order to

dry their clothes."

The result of the war council may be given in Murray's words:

"The enemy was greatly superior in numbers it is true; but when I

considered that our little army was in the habit of beating the enemy,

and had a very fine train of artillery, that shutting up ourselves at

once within the walls was putting ail upon the single chance of holding

out for a considerable time a wretched fortification—a chance which an

action in the field could scarcely alter—at the same time that it gave

an additional one, perhaps a better, I resolved to give them battle, and

if the event was not prosperous, to hold out to the last extremity, and

then to retreat to the Isle of Orleans or Coudres with what was left of

the garrison to wait for reinforcements. This night the necessary orders

were given."

At 7 o'clock in the morning of April 28 the British army was in

motion—formed in two divisions, the right column, issuing from St.

John's Gate under Colonel Burton, contained the 15th, 58th, 2nd/60th,

and 48th; the left column from St. Louis Gate, was commanded by Colonel

Eraser, and contained the 43rd, 47th, 78th, and 28th. Each column of

approximately 1200 men.

A corps of reserve, under Colonel Young, included the 35th and 3rd/60th.

Major Dalling, with the light infantry (about 370 men) covered the

right, Ilazzen's Rangers and McDonald's Volunteers (about 300 men in

all) the left.

There was little of pomp and circumstance in the appearance of this

little army. The rigid customs of the day, which made the men don their

best for battle and inculcated extra care in the dressing of queue and

pipeclaying of belts, could have little adherence after the winter

experience of Quebec, for the clothing was patched and ragged and

replaced in many cases by such homely garments as could be improvised by

the men themselves. The service buckled shoes had long since been

replaced by the Soulier of the country; many of the men were maimed or

disfigured by frost bite, but no doubt from sheer custom they turned out

at their smartest, and the drummers at the head of each corps, who in

those days occupied the place of both band and buglers, tapped out their

bravest ruffies.

But if the marching battalions as they filed out of the city gates

showed to little advantage, what can be said of the wan-visaged details

left behind to guard the city ? The greater number of them were men who

had willingly donned accoutrements to take their share, but who up to

that day had been lying in the hospitals. Even men too ill to stand had

their firelocks, bayonets, and ammunition near them, that as many as

possible of those fit to march might go out.

Of the women no writer has left us any description. We know only that

they had suffered little from the rigours of the winter, but one may

hazard the opinion that on this morning in April, and during the

preceding night when the weary soldiers had returned from their

dispiriting recon naissance, they were doing, and had done, heroine's

work in tending the sick and cheering the down-hearted. They were

accustomed to war and accustomed to hard living, but they were women for

all that, and had women's hearts under the rough exterior, and women's

pity for these harassed men marching through the snow-drifts to

encounter from which many did not return.

For the rest, the town was empty. Almost the entire population had been

driven out, as has been said, "to prevent the necessity of guarding

within as well as without," and Murray and his following had to pass no

inquisition of curious citizens—critical, unfriendly, or indifferent.

Outside the walls the two columns would be in open country. Burton's

column on the right, with a clear view of the St. Charles valley on the

one side, the open cultivated land bordering the Ste. Foy road on which

they marched, ahead of them ; Fraser's column on the Sillery road, as

soon at> they ascended the rise to the Buttes-a-Neveu would have an

uninterrupted view over the country stretching gently away to the west,

with the St. Lawrence and its rough precipitous banks on their left

hand. Arrived abreast of the eminence the columns formed line and took

up a position which it was Murray 's intention to hold and

fortify, and for this purpose he had burdened his men with entrenching

tools.*

The line on the "buttes" could not have been formed before 8 o'clock,

and while the battalions were taking up their positions Murray rode

forward and reconnoitred the enemy.

His view extended over a stretch of open land, falling very gradually

towards the west. On his left front, a mile away, the terrain was

blocked by the woods which, commencing about the region of the Anse au

Foulon, stretched for some distance towards the Cap Rouge ; all this

open land, which in summer time was cultivated, was flecked with patches

of half-melted snow which lay thick and slushy in the hollows. The

ground surface was soft and muddy, but below this was still the hard

bone of a frost that had extended several feet into the soil. Below, in

the bottoms near the wood, the ground was marshy about the bases of the

two little eminences, which were a feature of the landscape, one on each

side of the Sillery road, where it entered and was lost to sight amongst

the trees. On his right front was the Ste. Foy road, bordered at

intervals by the houses of the habitants; a short mile away Dumont's

Mill was prominent, and beyond the road could be traced a considerable

distance towards Ste. Foy. Along this road could be seen the marching

columns of the French army. Some part of the enemy had already taken

ground to their right and reached the outskirts of the wood. Another

body was active about the mill; more troops were continually arriving.

Towards Dumont's Mill scattered groups of the British light infantry

were already m action.

We are told that twenty pieces of artillery were taken out, two by each

battalion. Although not specifically stated, it may be assumed that

these were man-handled—it would, in fact, have been impossible to use

horses across country, having in view the partly dissolved snow which

covered the ground ; and even assuming that each gun with its tumbril

was unaccompanied by any other vehicle for reserve ammunition, not less

than from four hundred to five hundred men would be necessary to drag

them into position. This was naturally an immense added labour which

seriously reduced the mobility of the troops, and the efficiency of

their volume of fire.

On the French side, combining the statements of the Chevalier de Levis,

M. de la Pause, and the account published in the Gentleman's Magazine of

1760 (being The French Account of the Transactions of the Army in Canada

"), we can follow the course of events pretty clearly. De Levis mounted

early in the morning and reconnoitred, believing that the English had

retired within the walls. He found, however, certain detachments of the

enemy (this must be the detachment of light infantry mentioned by Knox :

" Early this morning our light troops pushed out and without difficulty

drove them to a greater distance "), and, being unsupported, he retired

before them. Meanwhile, ten companies of Grenadiers, forming the van of

the French army, occupied a position a little in advance of the knoll,

which still can be seen just north of the Sillery road; but De Levis

gave orders that five of these should occupy Dumont's Mill on the Ste.

Foy road, which he intended should cover the left of his line. The

remaining companies of Grenadiers retired to the small eminence already

mentioned. Orders for the five brigades, which in the meantime were

marching down the Ste. Foy road, to deploy were given, and De la Pause

was told off to direct them to their positions as they arrived.

It was at this period that Murray made his observation. It was, in his

words, the " lucky moment." The order for an advance in fine was given,

the drums beating the " gcnerale." lie hoped to destroy the French force

before it could fully deploy.

An advance in line over the rough open country, covered in many places

by slushy snow-drifts, must have been slow, some 1300 yards were to be

covered, and at least half an hour would elapse; the English force was

moreover descending the gently sloping ground and losing the advantage

of its first position. The time was invaluable to the French ; the two

first brigades had taken up their position on the left—they consisted of

La Sarre and De Berry; the third brigade of marine battalions was taking

up its position in the centre. La Reine and Royal Roussillon were still

marching under cover of the woods to form the French right.

The first contact was at the mill known as Dumont's, which was now held

by the French Grenadiers. The mill occupied the site, or very near it,

of the present monument to De Levis and Murray, standing at the end of

the "Avenue ties Braves," which indicates the centre lire of the

conflict. Here Dallmg's Light Infantry made a vigorous attack and drove

out the Grenadiers. The Chevalier Johnston gives a spirited, if somewhat

inaccurate, account of this, describing the "Highlanders" (sic) and

Grenadiers attacking each other with bayonet and dagger and taking and

retaking the houses several times, until the Grenadiers were reduced to

fourteen men. While this was going forward the English artillery had

caused heavy casualties on the French left, and De Levis ordered a

retirement within the shelter Of the woods, that they might reform and

await the attack of the brigades now forming on the right. This

movement, while it saved the French left from being overthrown by the

advancing English, also had the effect of leading Major Dalling's men

into a too vigorous pursuit of the French Grenadiers, who were flying

from Dumont's Mill. Dalling hail unfortunately been wounded, and perhaps

his men were out of hand ; at all events, they were severely handled by

the French left brigades now retired within the wood ; they were forced

back and almost annihilated (losing 218 men killed and wounded, almost

two-thirds of their member), dispersing across the front and masking the

fire of Colonel Burton's battalions. Seeing this confusion, Murray

personally hurried up Otway's (35th Foot) battalion to cover his right.

While this partially successful action was going forward on the right,

the left battalions of the English line had taken possession of the

little eminence, south of the Sillery road, wdiere now stands the Mereci

Convent, on which stood two small redoubts partly ruined, remnants of

Townshend's entrenchments of the previous year. Unfortunately, success

here was short-lived. The brigades forming the Freneh right, La Reine

and Royal Roussillon, •which were now formed in the wood facing our

left, and consisting of over 2000 men, easily outflanked the English

battalions, and overpowering the Rangers and McDonald's Volunteers, who

formed the only flank protection. Here the gallant McDonald 2 was

killed, and many others. De Levis claims that this flank attack was

carried out by the Roussillon brigade only, with some Canadians of the

brigade La Reine, the regulars of the latter having moved off to the

left through a mistake, and the truth of this is borne out by the light

losses of the two battalions forming it. Even with this disadvantage,

the numbers available were not less than 1700 men, opposed to two weak

battalions of the British, and a small body of Rangers and Volunteers,

which had become somewhat unsupported by the general inclination of the

remaining battalions to the opposite flank.

The result was inevitable, and the whole British left crumpled up, after

a gallant resistance, in which they lost half their strength. Murray did

all that was now possible, and his second reserve battalions, the

3rd/60th, as well as the 43rd from the centre, were brought up to

endeavour to stop the rout on the left, but without success, the

battalions arrived too late.

On the English right also the inevitable outflanking by a superior force

took effect. Brigadier de Bourlamaque, having rallied the brigade La

Sarre, and taking advantage of the confusion caused by the overthrow of

the light infantry, advanced the whole brigade, doubtless supported by

that of De Berry, and surrounding the English left, finally recaptured

the mill and broke the English resistance. The 15th and 48th bore the

brunt of the fighting in this section. The English centre, meanwhile

facing at short range the wood in which the French marine brigade was

concealed, could do but little, and hardly contributed to the fortunes

of the day.

A general retreat was enforced, and the disadvantage of having to retire

up-hill became apparent. It was impossible to save the guns (it is

stated that two only were saved) ; even some of the wounded must be left

to the mercy of the enemy. The redoubt in rear of the English left,

which, though but half complete, deceived the enemy, and held their

advance for ten minutes (Mackellar's report), enabled the English to

maintain some order in their retreat.

Whatever opinions may be formed on the battle tactics, there can be no

argument as to the fighting bravery of the British troops. The battle

lasted for three hours, we are told, i.e. presumably from the first

contact at Dumont's Mill, that is to say, the retreat commenced about

one o'clock. Out of a total of rather over 3000 men engaged, the loss in

killed and missing, including prisoners, was 41 officers and 255 men,

and of wounded, 89 officers and 724 men.* Thus at least thirty-three per

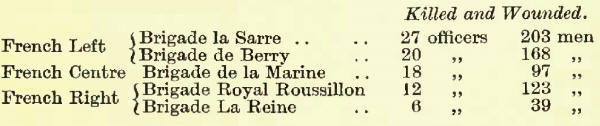

cent, of the men were put out of action. On the French side De Levis

gives a return of 933 f killed and wounded in the action alone, and it

was believed that this statement was short of the facts. The details of

the casualties in each regiment are given in De Levis' Journal, and

these are of interest, whether accurate or not, as showing where the

brunt of the fighting fell. Summarised these are:

Thus upwards of 2000 casualties in the combined forces, estimated by me

at about 10,000 men, testifies to the truth of Knox's remark, that " the

action was immensely warm for near two hours." The figures above,

moreover, confirm the claim that the action on the British right was

within a measurable distance of success, but all the conditions were

against probability of final victory.

It seems impossible to contend that Murray was justified in quitting the

high ground and advancing to meet the enemy. The position on the

Buttes-a-Neveu was not entrenched, it is true, although it certainly had

been the intention to entrench it, and even at the eleventh hour, by

taking entrenching tools, Murray had evident intention of advancing no

further—he had prepared fascines, and with these a considerable cover

could have been obtained without digging, or even driving in pickets,

which the hard state of the ground prevented. The position was within

easy reach of the town, and his flanks were tolerably well assured by

the fire of the block-houses and from the walls. On the other hand, had

this position been held De Levis would probably not have attacked —

there was no special reason why he should. His position from Dumont's

Mill to the Foulon gave him good communications, and his object in

coming at all was less to make a regular siege than to be at hand should

the expected French reinforcements enter the river.

If De Levis had chosen to play a waiting game Murray could scarcely have

remained for any length of time on the " buttes " to await an attack ;

his sickly troops would have melted away within a few days if exposed to

the wet and cold of a bivouac or even an encampment, and he would

probably have been obliged ultimately to retire

*In a letter to Bougainv ille, dated May 3, Rourlamaque writes : "Nous

perdrons Velite des officierMl La Sarre, Berry, Beam, et la Marine,

surtout, sont eerase, a ins i que les Grenadiers Mille hammer je erois

tues ou blesses," and adds, " Ne dites de eette lettre que ce que vous

eroirez convenable; surtout diminuez notre perte." within the walls.

Perhaps it was this reflection which causcd him to seize what he thought

was the "lucky minute" and endeavour to overthrow the French army whilst

it was'Tstill in column. It is dillicult, perhaps impossible, for us to

conjure up the circumstances in which Murray found himself, and the only

criticisms that can, with any confidence, be offered, are that if an

advance beyond the "buttes" was desirable, it should have been to a

lesser distance, not bringing his line into the low ground ; and that

had he concentrated his artillery on the mill and the moving French

columns at a range of, say, half a mile, he would probably have

inflicted heavy loss on the enemy, while suffering very slightly

himself, and then, if attacked, he could have regained his vantage

point.

That his correct course was to remain passive within the walls,

suffering De Levis to take up his position on the " buttes," cannot for

a moment be admitted. The Pyrrhic victory which De Levis had gained left

his troops little desire for an assault, which under other conditions

they might have undertaken with considerable chance of success.

A critic, writing in the Annual Register of 1760, in a judicial and not

unfriendly strain, says : " It is hard to understand how the chance of

holding out a fortress should not be lessened after a defeat of the

troops which compose the garrison," but he adds, " These are matters not

so easily comprehended by those who are at a distance from the scene of

action." To this criticism I will only reply in addition to what has

been already said. It would have been impossible to hold Quebec during

the winter without the outposts at Cap Rouge and Ste. Foy, or to

withdraw those outposts without advancing in force beyond the walls

(hence a theory which relied on passive defence only, would have broken

down in practice), though the argument still remains that having once

withdrawn the outposts there was no necessity for risking further

battle; but in this judgment I find it impossible to agree, for the

reasons already given.

Once within the walls, Murray's chief object was to restore the shaken

morale of his troops. An order was at once issued which is worth quoting

; it concealed nothing, and appealed direct to the hearts of the men :

"The 28th of April has been unfortunate to the British arms, but affairs

are not so desperate as to be irretrievable. The General often

experienced the bravery of the troops he now commands, and is very

sensible they will endeavour to regain what they have lost. The fleet

may be hourly expected, reinforcements are at hand, and shall we lose in

one moment the fruits of so much blood and treasure ? Both officers and

men are exhorted patiently to undergo the fatigues they must suffer, and

to expose themselves cheerfully to some dangers—a duty they owe to their

king, their country, and themselves."

On April 30 Murray sent a despatch to General Amherst, in which he

detailed his situation :

"The intelligence I had the honour to communicate to you by Lieut.

Montressor of the enemy's designs proves true.

"The 17th of this month I was informed that they had everything in

readiness to fall down the river, with eight frigates, the moment it was

clear of ice, and it did not break up here sooner than the 23rd,

consequently, as the country was covered with snow and the earth

impenetrable, it was impossible to attempt intrenching myself on the

Heights of Abraham, which I formerly told you was my plan of defence,

before the 25th, and even then, as will no doubt appear by the Journal

of the engineer-in-chief, it was hardly possible to drive in the first

pickets, the thaw having reached no further than nine inches from the

surface (here follow details already described).

"As we have been unfortunate I am sensible I may be blamed universally

at home ; but I appeal to every officer in the field, if anything was

wanting in the disposition or my endeavours to animate the men during

the whole affair. The superiority which these troops had acquired over

the enemy ever since the last campaign, together with the fine field

train we were furnished with, might have tempted me with an action,

supposing I had not been thoroughly convinced of the necessity of it.

"We lost in the battle about one-third of our army, and have certain

intelligence that the enemy had no less than 10.000 men in the field. .

. . Had we been masters of the river, in which it is evident ships may

safely winter, they would never have, made the attempt (my italics).

"I must do the justice to Colonel Rurton in particular, and to the

officers in general, that they have done everything that could be

expected of them. . , ."

For a day or two the bonds of discipline were broken, and the men were

inclined to panic and despair. " Immense irregularities were hourly

committed," says Knox, and prompt stern measures were necessary. On the

30th a man was hanged without trial " for an example to the rest." All

liquor " not belonging to the King " was spilled to prevent the men from

getting it. Murray and his officers were everywhere encouraging the

garrison and showing an intrepid activity. Within two days, while the

French were entrenching on the " buttes " and busy landing their

artillery and stores at the Foulon, guns had been dragged from the river

front and mounted on the walls, platforms built for them, and embrasures

cut in the weak parapet which formed the landward defences. Almost at

the start another piece of ill-luck occurred in the destruction of the

great block-house built outside the St. Louis gate. Knox describes this

as accidental, but Murray seems to attribute it to the enemy's fire, lie

adds : " This was unlucky, as it was our most advanced work, roomy,

strong, and hors dHnsulte, having three pieces of cannon in it." Being

considerably advanced towards the dominating position of the " buttes,"

this block-house was important as preventing the enemy from working on

their batteries.

By May 2 the efforts of the governor and his officers had so far

recovered the position that Knox was able to record :

We no longer harbour a thought of visiting France or England, or of

falling a sacrifice to a merciless scalping knife. We are roused from

our lethargy; we have recovered all our good humour, our sentiments for

glory, and we seem, one and all, determined to defend our

dearly-purchased garrison to the last extremity."

The activity of the garrison, in fact, knew no bounds. Guns there were

in plenty, and fresh batteries were constantly being opened, which

caused serious difficulties to the attackers. De Levis tells us :

"Les ennemis, qui a tous moments dimasquoient des pieces nous

retardoient beaucoup par des precautions qu'il falia it prendre ; les

boulets plongeant derrierc les hauteurs, il y avoit peu d'endroits ou

Von fut a couvert, Von fut mime oblige d'eloigner le camp."

On May 1 the Racehorse, Captain MacCartney, was despatched to convey to

Lord Colville the position of affairs, and to urge the early return of

the fleet. As it turned out, it is unfortunate that this was done, for

the Racehorse made Halifax in an exceptionally quick passage of ten

days, and apparently passed Colville on the voyage. Governor Lawrence,

however, thought it advisable to open the despatches (which were for

Amherst), and wrote to Pitt by the Richmond on May 11, giving him a very

pessimistic view of the situation. It was this news that arrived a few

days before the intelligence of the final defeat of De Levis, and caused

great consternation in England. Murray's letter to Amherst has already

been partly quoted on p. 238. It was a plain statement, and disguised

nothing, but evidently the General felt that the support given him had

been meagre, yet it gave his enemies a handle for much misrepresentation

of which in after-years they made use.

The weather was improving, sorties were constantly made at night of

small parties to harass the enemy. A detachment was maintained outside

the walls at night to guard against surprise. A heavy fire on the

enemy's works was kept up day and night; up to the 3rd (May) no fewer

than 4000 rounds had been fired. The convalescents and the women bore a

hand making wadding for the guns, and filling sandbags- a hundred

precautions were taken which arc detailed in Murray's and Knox's

Journals. Every one was busy and worked with a will Discipline was

severe. The Provost "received orders to hang all stragglers and

marauders."

On May 5 and 6 De Levis records, " Les travaux n'avan-cerent pas

beaucoup ; on perdoit toujours quelques hommes."

It was not until May 11 that the French batteries were able to open

fire. The St. Louis and La Glaciere bastions were chosen for attack, and

three batteries of six, four, and three pieccs were prepared.

Fortunately for the garrison the pieces were old and of little power,

and the powder was bad. Not more than twenty rounds per piece could be

fired in the twenty-four hours, and even then some of the guns burst.

"Le peu de poudre et le peu d'effet qu'on devoit attendre de cette

artillerie qui etoit d'ailleurs trop eloignie obligerent M. le Chevalier

de Levis, pour ne se trouver totalement depourvu d'ordonner qu'il ne fut

tire que vingt coups par piece dans les vingt quatre heures."

Murray's anxieties so far as artillery attack was concerned were greatly

diminished, and, indeed, the machinery for killing in those days might

be described as honestly clumsy, from the flint-lock muskets,

ineffective beyond fifty yards, to the heavy siege 24-pounder, of which,

by the way, De Levis says he possessed but one. Little could be done

unless at close quarters, and the days were still distant when men were

to set themselves to devise scientific methods of dealing death.

"Singular Guillotin" was still a respectable practitioner, and cured the

bodies that one day he would destroy. Zeppelin, inventor of murder

machines for the destruction of women and children, was still in the

womb of the future, and the unnamed scoundrel who devised poisonous gas

as a means of attack was as yet undreamt of. Murder by these means would

not have been tolerated at a period when gentlemen fought like

gentlemen. Let us hope that the modern professors of the cult of

indiscriminate slaughter will, to borrow a thought from the Sage of

Chelsea, join the Ghost of Guillotin wandering through centuries on the

wrong side of Styx and Lethe, hand in hand with William the Outcast!

"There are crimes that obliterate the past and close the future."

We must remember, however, that if the energy of the defence kept the

enemy at a distance, still the walls were bad. It was on the 12th that

Murray noted:

"The chief acting-engineer reported to me, at four this afternoon, that,

having observed the enemy direct their fire very briskly to the

above-mentioned post (La Glaciere Bastion) he had been out to observe

the effect, and was surprised to find it so great, owing, as he

supposed, to the rottenness and badness of the wall. . . . This was

matter of astonishment, the enemy having fired but a short time, and at

such a distance as rendered the effect very surprising."

But a danger greater than the effect of De Levis' weak artillery was the

state of the sickly garrison, deprived of all means of obtaining the

fresh food which was essential to remove the taint of scurvy, and when

at 11 o'clock in the forenoon of May 9 our old friend the Lowestoft

frigate worked up past the Isle of Orleans and saluted the garrison with

twenty-one guns, we can imagine the joy and relief of the soldiers, once

more in touch, after seven terribly trying months, with that long arm of

England which reaches across all the seas. "The gladness of the troops

is not to be expressed; both officers and soldiers mounted the parapets

in the face of the enemy and huzzaed with their hats in the air for

almost an hour." The vessel was but the advanced guard, and on the 15th

the Vanguard and Diana arrived, under command of Commodore Swanton.

*An expression of opinion, worth recalling, written in 1797 by John

Almon, is the following: "Phlegm, sullennesR, inhumanity, and a most

inordinate love of power, are the characteristics of a German mind. He

only delights in riot and homicide, like his Thracian god Mars, to whom

he sacrifices many human 'victims, and to whom he pours profuse

libations."

The re-establishment3 in the St. Lawrence of sea-power, which should

never have been relinquished, settled the question; De Levis recognised

that the Court of France had abandoned hope in declining to enter the

contest by sending relief.* He had done his possible, and done it well,

with the small means at his disposal. He decided to raise the siege and

retire to Montreal, leaving garrisons at Pointe-aux-Trembles, Jacques

Cartier, and Deschambeau, as he retreated.

No time was lost in asserting the value of naval power. It appears that

the French had a detachment on the Beauport side, who took Swanton's

ships for Frenchmen, and reported accordingly to De Levis, " upon which

it was concerted between Commodore Swanton and myself," wrote Murray in

his Journal :

"that he should attack the (French) frigates with the first flood-tide

in the morning (the Vanguard and Diana arrived in the evening, probably

in the dusk), and, to persuade the enemy the ships that came up were not

our friends, that I should beat to arms about one in the morning, as if

much alarmed."

The ruse was quite successful,! and before dawn the French commander,

the gallant Vauquelin4 though surprised and hopelessly outclassed,

fought his ship, the AtaJante, to the last, and, refusing to lower his

colours, was taken prisoner by a boarding party. The l'omone was driven

ashore and burned, and all the transports destroyed excepting a small

sloop of war, La Marie, which, by throwing her guns overboard, was

enabled to escape up the river. This naval action had an effect on the

linal operations of the highest importance, for it deprived the French

not only of the greater part of the stores that had been accumulated on

the transports, but necessitated the abandonment of all the equipage

that they had on shore, and, in their then circumstances, this was a

decisive factor in preventing the French army again taking the field

with any hope of success.

Thus ended the siege. The town had been invested for seventeen days

only, but the energy and resource of Murray, who, with a ragged, sickly

garrison (of 2000 effective men) had resolutely maintained his position

with no hope of relief, except from the sea, compares to his credit with

the conduct of De Ramezay in the previous September, when, with a

garrison of at least equal numbers, he surrendered before a gun was

fired against his walls after an investment of three days, while an

army, which should have been capable of relieving him, was close at

hand.

I have criticised General Murray's tactical movements in the

foregoing—but what can be said in favour of De Levis ? His plans were

bold and skilfully executed, but were they wise? Should he have exposed

the whole available naval strength of France and the greater part of his

military resources to the hazard of action when by waiting he could at

least have lost nothing. Had the expected French squadrons arrived first

in the river Murray must have surrendered without the loss of a French

soldier. Had De Levis awaited the event at St. Augustin beyond reach of

Murray's army the arrival of the English squadron would have left him

intact and in a position powerfully to dispute—practically, I think, to

render impossible—Murray's subsequent ascent of the river to join

Amherst at Montreal. Had matters fulfilled his best expectations and

left him master of Quebec, his strength to oppose Amherst must have been

greatly weakened. Had Montreal been held, the peace which even then was

talked of would probably have left Canada to the French. French writers

of the period called this the Folly of De Levis. I think they were

right; at all events, Murray's defeat on April 28 was turned to victory,

and De Levis, having staked everything, lost all. There was nothing left

to hinder Murray joining Amherst; nothing of any great value to hinder

Amherst or Haviland in the converging movement on Montreal. To Murray,

for his strong resistance in desperate circumstances, and to Swanton,

for his timely, effective co-operation, belong the laurels of the

conquest of Canada.

Monsieur le Capitaine de Malartic of the regiment of Beam was the

officer left behind by De Levis to carry on negotiations with Murray

regarding the prisoners of war, and, if we are to believe implicitly all

that officer wrote to his chief, we obtain a certain insight into

Murray's state of mind :

'III m'a aussi dit qu'il commande dans cette partie et M. Amherst dans

la sienne, qu'il n'est pas tracassier, n'aime pas les difficultes et

qu'il n'en auroit jamais vis-a-vis de vous, parcequ'il vous aime, vous

estime, ayont vu que vous aimez a vous baitre. ... II a voulu je crois

me tirer le ver du nez ce matin en me demandant ce que vous vouliez

faire, qu'il vous etoit impossible de conserver la eolonie. ... II

voudroit fort qu'on capitulat avec lui, a ce qu'il a dit d M. de Belle-combe

qu'il feroit aux troupes le meilleures conditions qu'on pourroit exiger.

M. de Bcllecombe I'a assure qu'il faudroit qu'il bataillat encore, s'il

vouloit prendre le Canada. II dit qu'il etoit bien assure que vous

saisiriez avec empressement toutes les occasions de combattre; mais que

I'armee ne peut pas subsister de I'air, et qu'on sera oblige de se

rendre Jaute de pain."

Whether this little story is quite true or not one has no means of

knowing. It is just possible that Murray's endeavour to "tirer le rer du

nez" of M. Malartic may have had some foundation in fact. Amherst was a

slow mover, though a sure one, and Murray may have had some not

unnatural ambition to settle the fate of Canada before the invading

armies could arrive at Montreal. Murray himself says nothing about it in

his Journal, but hints at the same idea in his letter to Amherst, quoted

at the end of this chapter. At a later date, indeed, writing to Pitt, he

gives rather the reverse impression: M. de Vaudreuil insinuated terms of

surrender to me which I rejected, and sent information thereof to the

commander-in-chief, who was then three days' march from Montreal." This

was, however, in August, and the state of the case was then very

different.

I will conclude this chapter with Murray's report to Amherst, written

immediately after the retreat of the French army. In this letter he

gives full credit to the far-reaching assistance of the navy.

" Quebec, May 19, 1760.

" Dear Sir,

" I have the honor to acquaint you that Monsieur de Levis last night

raised the siege of Quebec, after three weeks' open trenches. He left

behind him his camp standing, all his baggage, stores, ammunition,

thirty-four pieces of cannon (four of which are brass 12-pounders), six

mortars, four petards, a large provision of scaling ladders, and

entrenching tools beyond number. Some of the field train we lost the day

of the action we have again recovered. What the King's troops have done

during this siege I dare not relate if I had time, it is so romantick,

and our loss, considering, has been very inconsiderable. I had intended

a strong sortie this morning, and for that purpose had the regiments of

Amherst, Bragg, Lascelles, Anstruther, and Fraser's, with the Grenadiers

and light infantry, under arms; but was informed by Lieut. McAlpin, who

I had sent out to make a small sally scion les Reigles (sic), that the

trenches were abandoned. I instantly pushed out at the head of these

corps, not doubting but I must penetrate their rear, and have ample

revenge for April 28, but I was disappointed ; their rear had crossed

the River Caprougc before I could come up with them. However, we took

several prisoners, stragglers, and much baggage which otherwise would

have escaped. I cannot help taking this opportunity of mentioning Major

Agnew in a distinguished light; he commanded the corps of the light

infantry, and old Addison.

"This enterprise has cost the enemy upwards of three thousand men, by

their own confession. They are now at their old asilum at Jacques

Cartier, and, for want of every necessary, must soon, I imagine,

surrender at discretion. We are very low; the scurvy makes terrible

havock. For God's sake send us up melasses, and seeds which may produce

vegetables. Whoever winters here again must be better provided with

bedding and warm clothes than we were. Our medicines are entirely

expended ; at present we get a very scanty supply from Lord Colvill's

squadron, which arrived this day; but Captain Swanton, in the Vanguard,

with two frigates, came into the bason from England the night of the

17th, and next day destroyed and dispersed the enemy's squadron. 1 have

not words to express the alacrity and bravery of Swanton, Dean, and

Schomberg—the honor they have acquired on this occasion should render

their names immortal.4 Our Louisburg friend, Monsieur Vauquelin, who

commanded the Freneh squadron, is taken prisoner, and his ship destroyed

; but poor Deane, after all, was over struck upon a rock, and I fear his

ship will be lost. Lord Colvill agrees with me that as the news I sent

you of April 28 may reach England and ala^m the Ministry, it is

necessary immediately to dispatch a frigate with advice to Mr. Pitt of

the happy issue of Monsieur de Levis' enterprise. I send Major Maitland

wTith my dispatches, and I hope he will reach London before the loss of

the battle is known there. The Journal of the siege, and of all my

proceedings since I had the honor to command here, are preparing for

you, and shall be transmitted by the first opportunity. We have received

the £20.000 sent in the Hunter—it is a poor sum for a garrison which has

had no pay sinee August 24. I find His Majesty has appointed me colonel

of the 2nd Ratt. of R. Americans. I am very thankful to him for if It

would have distressed me had Burton, as I hear was intended, purchased

from Prevost over my head. I could have raised money enough for that

purchase, had I been consulted ; but it is better as it is, and I dare

say you only recommended Mr. Burton's affairs in the event of my getting

the rank before him. I must think so until you tell me otherwise

yourself,5 for I have always flattered myself I had some share of your

friendship, and am very confident I have done everything in my power to

acquire it.

"This instant Lieut. Montresor is arrived, and has delivered to me your

letter of April 15. The orders in it shall be obeyed to the best of my

ability. Mr. Montresor tells me you would not credit the accounts I sent

to you of the enemy's designs upon Quebec, but you will find they are

not so prudent (pessimistic) as you imagined. I flatter myself the check

they have met with here will make everything very easy afterwards. I do

declare to you upon my salvation that they had an army of 15,000 men

before Quebec, ten of which consisting of eight battalions of regulars,

two of the troupes de colonie, and the Montrealists, were actually

engaged in the battle of April 28 ; the other five thousand were the

Canadians of the lower Canada, who joined them after the battle, j The

regulars are still at Jacques Cartier with a few Canadians who serve in

those corps, and in all about five thousand men. They have little powder

left, and I am confident have as little provisions. Deserters come in

dayly. If you make haste, for the honor of their colours, they may give

you battle, but if you do not, for want of something to eat, they will

surrender to me, for I have destroyed all the magazines they had

prepared for the siege of Quebec. You may depend upon my pressing them

if I have but five hundred men. It shall never be said with justice that

anything has been wanting in me; but if I know the country, and I

believe I have a tolerable idea of it, I must beat their army before I

can open your passage by the Isle-aux-Noix. The enemy are wiser than to

divide their force, and, be assured, they have only two hundred of the

troupes de colonie and four hundred Canadians at that post. When they

know of your motions, I don't know w hat they may do. I shall watch

theirs, and take every advantage of them in my power. I make no

difficulties, the enemy have supplied us with boats or battoes, but Cod

Almighty has reduced the large body of troops which were left at Quebec

to an inconsiderable number, and had not the enemy's fleet in the river

been destroyed, I apprehend without proper craft I could not have been

master of it. . . . Montresor tells me you seemed surprised at the

precautions I had taken in building block-houses in the winter, but you

will not be so when you hear the designs which were formed and partly

attempted against me in the winter and when you see the place—I believe

very few of the gentlemen who left their posts to follow their pleasures

on the continent gave themselves the trouble to examine the place and

our situation. The fact is, we were surprised into a victory 6 which

cost the conquered very little indeed, and it was very natural for these

gentlemen to represent that there could possibly be no danger or

difficulties here, since they had left their corps in garrison. ..."

|