|

IN a country newly

opened for settlement the land regulations are of the greatest

importance to the inhabitants and the prospective settlers, and in the

early days of Upper Canada they were the first rules that had to be

observed. They were, however, of the simplest. The settler held his

lands under a certificate signed by the governor and countersigned by

the surveyor-general or his deputy. The locations were decided by

chance, lots being drawn and situations fixed accordingly. The

certificate set forth that at the end of twelve months the holder should

be entitled to a deed and become possessor of his land with power to

dispose of it at will. Now if the original grantee had held his land

secure until the patent was handed him, no confusion would have ensued.

But so soon as the allotments were made in 1784 and certificates issued,

barter and exchange began. Some settlers were compelled by sheer

necessity to sell or mortgage a portion of their lands; others found

that their locations were too small to admit of successful farming

operations and added to them by purchasing from their neighbours. So

under these unsafe conditions of title, property was constantly changing

hands. The Land Boards, constituted in 1788, attempted to check land

speculation, which had made its appearance even at that early date in

the history of the province, by issuing all new certificates subject to

the condition that lands so granted would be forfeited if not actually

settled upon within the year. They were also not transferable without

the sanction of the board.

These regulations were

but a rude attempt to maintain a proper system of registration. They

could not control the larger grants to officers nor affect the lands in

townships only in part surveyed. The exchanges, purchases, and

mortgaging went on unchecked, and for ten years the only foundation of

title was the original certificate or a scrap of paper that had at some

time taken its place. Simcoe found that, although ten years had elapsed

since the first allotments had been made, scarcely a single grant had

been ratified, and that there seemed to be a disposition in many persons

to deny the necessity of the exchange of certificates for grants. This

state of .affairs was viewed with extreme dissatisfaction by those who

had any large landed interest in the province and could understand the

gravity of the situation.

The fourth session of

parliament paved the way for a general issue of patents by providing for

the registry of all deeds, mortgages, wills and transfers. Simcoe had

the advice of his law officers and his legislative councillors, and

Cartwright, foremost among the latter, gave him the benefit of his views

which were sound and well considered. He had not a very favourable

opinion of Governor Simcoe as a lawyer, nor of his colleagues in the

executive council. " They are not very deep lawyers," he remarked. Mr.

Hamilton also laid the whole matter before a London lawyer, while upon a

visit to England in 1795, as a member of the community and not in his

capacity of legislative councillor. For this he was called to account by

the governor who thought the intention should have been mentioned to

him. The moot point was whether the original certificates should be

recognized by the patents, or the current deed or transfer. The wise

view prevailed at length, and when patents were finally issued under the

great seal of the province they were so issued to the holders of the

land and not to the original possessors under the Land Board

certificates.

Land speculation was

rife in the province, and the council had to refuse many applications

for grants from persons who did not intend to become active settlers.

Even with this care many allotments were made for speculative purposes,

and the entries for many townships had eventually to be cancelled for

non-settlement. Officers of the British army in the Revolutionary War

made demands for large tracts of land in Upper Canada as a reward for

service Benedict Arnold was an applicant for a domain in the new land.

He wrote to the Duke of Portland on January 2nd, 1707: " There is no

other man in England that has made so great sacrifices as I have done of

property, rank, prospects, etc., in support of government, and no man

who has received less in return." The moderate area that he desired was

about thirty-one square miles. Simcoe was asked Ins opinion of such a

grant, and on March 20th, 1798, he replies that there is no legal

objection but that "General Arnold is a character extremely obnoxious to

the original Loyalists of America." From the date of this letter it will

be observed that during his residence in England, after leaving Upper

Canada, Simcoe was consulted by the government upon Upper Canadian

affairs. He, himself, on July 9th. 1793, received a grant of five

thousand acres, as colonel of the first regiment of Queen's Rangers. The

operations of colonization companies began after Simcoe left the

country, and, interesting as some of them are, they do not fall within

the term of this story. The Land Boards, which had existed since 1788,

were discontinued on November 6th, 1794, after which date the council

dealt with all petitions for large grants of land, the magistrates of

the different districts dealt with allotments of small areas of two

hundred acres.

The beginnings of trade

and commerce in a province that now takes such a great and worthy place

in the world as a producing power are interesting and to trace and

chronicle them is a useful task.

'lie fur trade was the

first and for many years the only source of wealth in the country

afterwards called Upper Canada. It was carried on by the great companies

as well as by individual traders. The Indians were the producers of this

wealth and the first, and, it may be said, by far the smallest, profits

came to them. Whatever small benefit was derived from the supply of

clothing and provisions which the traders bartered for the peltry, was

offset by the debauchery and licentiousness that follows wherever and

whenever the white man comes into contact with an aboriginal race.

The tribes were, often

ruled by these traders who flattered the chiefs, hoodwinked the

warriors, fomented quarrels to serve their own ends and did not scruple

to attribute to governments policies and compacts which they had never

contemplated nor completed. Rum was the great argument that preceded and

closed every transaction. The natural craving for this stimulant was so

well served that after a successful trade an Indian camp became a wild

and raging scene of debauchery, wantonness and license. During the

dances that accompanied and fanned these orgies the great chiefs changed

their dresses nine or ten times, covered themselves with filthy

magnificence and vied one with the other in the costliness and

completeness of their paraphernalia. Such a trade could add but little

to the capital of a country; it served to enrich those who had made the

adventure in goods, but no permanent investment of capital was necessary

for its maintenance, and when the source of supply was drained it

disappeared and left the Indians worse off than they were before its

advent and development.

Simcoe saw the positive

evils and negative results of this factitious trade and endeavoured to

control it. He proposed as a means to this end to confine the traders to

the towns and settled communities, and thus prevent them from crossing

into the Indian country. By this regulation the Indians would become the

carriers of their own furs, and coming first into contact with the

settlers would part with their wealth in exchange for provisions and not

spirits. The settler would for his part receive skins that were as ready

money when that article was scarce. Thus an internal fur trade would be

established, and a certain portion of the wealth would be retained in

the country. With the advent of hatters, the craft they carried on would

consume a great number of the skins and the contraband trade in hats

would gradually diminish. In 1794 three hatters had already come into

the province to establish themselves.

One result of this

trade and barter between settler and Indian was that an illegal exchange

sprang up between the former and the Americans who settled New York

state. All the cattle, many of the implements, and much of the furniture

of the first Upper Canadians were obtained by the sale of furs in this

manner. Not only did American products thus find their way into the

country, but goods of the East India Company and even articles and

materials made in Great Britain. Smuggling was too common and too

convenient to be looked upon with disfavour. The frontiers lay open and

unprotected, and the thickly wooded country made detection impossible

even had there been an army of preventive officers, and these were, in

fact, but few.

This dishonest trade

was beyond the power of government to control, but Simcoe was impressed

with the importance of promoting commercial connections with the

republic. He recommended the establishment of depots of the East India

Company at Kingston and Niagara to sell merchandise, chiefly teas, to

the people of the state of New York. He believed his province to be the

best agricultural district in North America, and pointed out how its

forests might be replaced by fields of hemp, flax, tobacco and indigo.

Hemp, as a source of wealth to the settler and of supply for the cordage

of the lake fleet, was a subject of his constant attention. The exports

of potash had begun to fall away somewhat during the term of Simcoe's

government ; affected by the war in Europe prices had fallen, and as the

land became cleared, and the area under crop more extensive this early

industry gradually waned.

The staple product of

the country was wheat and Simcoe paid the greatest attention to

developing this source of prosperity and wealth. Pork came next in

importance as an article for export and for domestic consumption. The

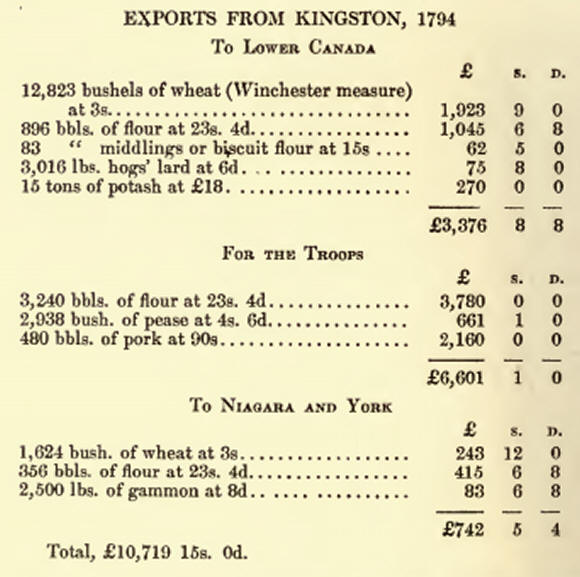

exports from Kingston during the year 1794 will show what progress the

colony had made. The figures are interesting as they mark a term of ten

years from the time the first kernel of seed was sown.

The most important

achievement that these figures set forth is the victualling of the

troops.

Agriculture, from

furnishing a bare subsistence to the people during the first few years,

had developed so rapidly that the surplus was sufficiently large to

supply York and Niagara where settlement was still active, and to

relieve the commissariat to a great extent from the necessity of

importing the staples—flour and pork. Upon the quantity of supplies

furnished for the troops mentioned in the statement, there was a saving

of £2,420 14s., so excessive were the rates of carriage. It cost ten

pence to freight one bushel of wheat from Kingston to Montreal. The only

means of transport were rude bateaux, the risk of total loss was great,

and after a most favourable voyage the actual loss from waste in

transhipment was very considerable.

Commerce in the country

was on every side beset with difficulties. Mr. Richard Cartwright thus

describes the business methods of his day: "The merchant sends his order

for English goods to his correspondent at Montreal, who imports them

from London, guarantees the payment of them there, and receives and

forwards them to this country for a commission of five per cent, on the

amount of the English invoice. The payments are all made by the Upper

Canada merchant in Montreal, and there is no direct communication

whatever between him and the shipper in London. The order, too, must be

limited to dry goods, and he must purchase his liquors on the best terms

he can in the home market; and if he wishes to have his furs or potash

shipped for the London market, he pays a commission of one per cent. on

their estimated value; if sold in Montreal, he is charged two and

one-half per cent on the amount of the sales."

But while the merchant

had these barriers of commissions and difficult transportation to

surmount the settler was in a most unenviable position. His sole sources

of wealth were his wheat and pork; these the merchants would buy only in

such quantities as they chose and when it suited them. They would pay

only in goods charged at the highest current prices, or by note of hand

redeemable always on a fixed date, October 10th. The absence of any

adequate and plentiful medium of exchange was a heavy burden upon the

struggling settler, who was in the hands of the buyer. The latter might

say "it is naught, it is naught," but, nevertheless, it was a real,

pressing and overbearing weight to be carried.

Simcoe had endeavoured

to loosen the grasp of the merchant, so far as his immediate power w

ould serve, by resuming the contracts for the purchase of supplies for

the troops and placing the responsibility in the hands of an agent who

would deal justly and equitably both in the matter of prices and

quantities. Although his duty was to the king primarily, yet it was

largely in the king's interest that his pioneers should have fair pay

and ready money, so that his duty was also to the struggling settler and

his little field of grain filling between the charred stumps of his

clearing. This was a step in advance, yet the main branch of the trouble

would remain untouched until some medium of exchange—in fact, a

currency—appeared to cover the small local transactions between buyer

and seller.

Simcoe, who left not

the smallest need of the country untouched in his exhaustive dispatches,

did not pass by this grave want. He had great faith in the intervention

of government in all matters pertaining to the welfare of the people. He

was ever making demands that argued the inexhaustible treasure-chest and

the beneficent will. When England was engaged in wars and treaties that

called for her utmost resources, a cry came out from Upper Canada for

grants for all purposes, from the founding of a university to the

providing of an instructor in the manufacture of salt.

He proposed a grand and

far-reaching scheme to meet the obstructions to trade which I have

mentioned. He proposed that Great Britain should send out a large sum in

gold which would form the capital of a company to be formed of the

executive and legislative councillors and the chief men in the province.

This sum, he says naively, should be repaid, if expedient, by the sale

of lands on Lake Erie. Inspectors were to be appointed whose duty it

would be to examine all mills and recommend such processes as would

reduce their products to a normal standard of quality.

The king's vessels

should be used for transport across the lakes. A large depot or

receiving-house was to be erected at Montreal, where all the flour was

to be pooled. For every barrel there received a note was to issue,

payable in gold or silver at stilted periods, and these notes were to be

legal tender for the payment of taxes. The freight of all government

stores was to be conducted by the company under a contract based upon

the prices paid for the three or four years preceding. The benefits that

Simcoe hoped to secure by this arrangement were: a provision for the

consumption of the flour produced, a medium of exchange instead of

merchants' notes, lower rates for transportation from Montreal, ease and

certainty in victualling the troops, a sure supply of flour for the West

Indies, and a stimulating effect upon agriculture as well as upon the

allegiance of the Upper Canadians. He wrote, "it cannot fail of

conciliating their affection and insensibly connecting them with the

British people and government." The lords of trade to whom the scheme

was presented could hardly have considered it, and Upper Canada was left

to work out its currency problems upon the safer basis of provincial

initiative.

The earliest canals

were all constructed within the boundaries of the upper province, but

during Simcoe's government they received no enlargement. They had been

constructed by Haldimand's order, and were maintained by the government,

assisted by a toll revenue of ten shillings for each ascent. All

transportation took place in bateaux, built strongly, with a draft of

about two feet, with a width of six and a length of twenty feet. These

were towed or " tracked " up the river and passed through the primitive

canals wherever they had been constructed. The first canal was met with

at Coteau du Lac, it consisted of three locks six feet wide at the gates

; the second was at Cascades Point; the third at the Mill Rapids; the

fourth at Split Rock. It was many years before these canals were

enlarged sufficiently to accommodate the schooners that sailed the upper

lakes.

These vessels were

constructed upon their shores, and never left their waters. In 1794

there were six boats in the king's service upon the lakes. These were

armed ; the largest vessels were of the dimensions of the Onondaga,

eighty tons burden, carrying twelve guns. They were built of unseasoned

timber, and their life was barely three years. It cost about four

thousand guineas to construct one of the size of the Onondaga, and the

cost of repairs was proportionately large. The merchant fleet on the

lakes numbered fifteen.

The rate of wages

throughout the province was high and labourers were scarce. The usual

pay for skilled labour was three dollars per diem; for farm labourers

one dollar per diem with board and lodging; for sailors from nine to ten

dollars a month; for voyageurs eight dollars a month.

Prices were

correspondingly high, salt was three dollars a bushel, flour eight

dollars a barrel, wood two dollars and a quarter a cord. The commodities

that we consider as the commonest necessaries of the table were beyond

the reach of the majority of the people; loaf sugar was two shillings

and sixpence per pound, and the coarse muscovado one shilling and

sixpence; green tea was the most expensive of the teas at seven

shillings and sixpence, and Bohea the cheapest at four shillings. The

cost of spices may be gauged by the rates charged for ginger, five

shillings a pound. A Japan teapot cost seven shillings and a copper tea

kettle twenty-seven. Fabrics were most expensive, "sprigged" muslin was

ten shillings and sixpence a yard, and blue kersey five shillings and

sixpence.

Every industry was

carried on under great difficulties, mills with insufficient stones,

saws and machinery; trades with the fewest tools and those not often the

best of quality. The salt wells in which the governor took an early

interest were hampered by lack of boilers or any proper appliances. In

four years only four hundred and fifty-two bushels of salt had been

produced at a selling price of £362. The only requisites at the wells

for the production of this most necessary staple were a few old pots and

kettles picked up casually. But the trades and manufactures served the

needs of the growing population, the units of which were self-reliant

and of a courageous temper. The actual population of Upper Canada is

difficult to arrive at accurately. It is stated to have been ten

thousand in 1791 when the division of the provinces took place. Writing

in 1795, de la Rochefoucauld places it at thirty thousand, but this

appears to be exaggerated. The militia returns sent to the lords of

trade by Simcoe in 1794 place the number of men able to bear arms at

four thousand seven hundred and sixteen, and Mr. Cartwright says that

upon June 24th, 1794, the militia returns amounted to five thousand

three hundred and fifty. The population during 1796 may have increased

to twenty-five thousand. For the breadth of the land this was a mere

sprinkling of humanity over an area that now supports above two

millions. |