|

While the packer enjoys

a private expedition into the wilderness once in a while, he regards it

rather as a holiday and a relief to his more strenuous daily round of

toil. To his mind, the only way to make money at packing is by the

conveyance of freight from point to point. The goods are carried at so

much per pound, the rate varying according to the distance to be covered

and the character of the country traversed.

In this respect the

packer makes hay while the run shines. In the early days of the Klondyke

geld rush, the fever-stricken metal seekers were forced to pay as much

as 2s. per pound for the transit of their goods from Skaguay. Even in

deserted Bennett to-day houses are standing with furniture rotting in

the apartments. These goods and chattels cost fiom 5d. per pound upwards

to bring in, and no one will take them out.

The freight park-train

runs on much the same lines as the tramp steamer, which sets out from

its home port and wanders hither and thither about the waters of the

globe, picking up merchandise here to be dropped there, and so on, never

knowing when the lights of home will be seen again. Similarly the

freight pack-train pulls out laden to the utmost with goods for a

certain place. Reaching this point, it finds that some freight is

waiting to be transported to another centre, and so on. An empty

pack-train is a loss on freighting work, and consequently no load,

however uninviting, is refused. Thus it roams to and fro through the

wilderness during the summer season, and it is only the approach of the

snow from the North which drives it home at last.

This is the class of

trade which brings the greatest financial roiurn to the packer. It

stands to reason that the less time in which he can cover a certain

distance at so muoh per pound, and the greater the number of

remunerative journeys he can make in a season, the higher his financial

return at the end of the year. The animals also do net suffer so

severely from the strain in packing freight as on private expeditions.

In the latter case an assortment of ungainly and bulky packages are

carried which of) en demand delicate handling, and which cannot be

divided up equitably as regards weight.. On the other hand, with freight

no such difficulties are experienced. For instance, suppose a large

consignment of flour has to bo packed a distance of two or three hundred

miles. The commodity if. divided into bags, weighing 100 pounds apiece,

slung on either side of each horse, the animal’s burden being 200

pounds. The load sits evenly upon its back, and neither impedes its

progress to the slightest degree nor occasions extreme fatigue. Then,

again, from one end of the journey to tho other, the packs are never

disturbed, whereas on private expeditions each load is opened out at

night, aiid has to be readjusted in the morning.

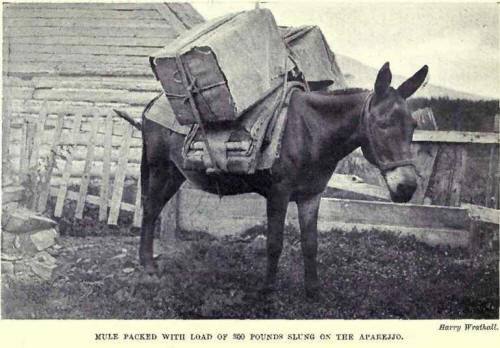

With freight, loading

and unloading every morning and night is a simple, straightforward

operation, especially when the apparejo is used, this being a saddle

specially designed for pack-train work, on which the loads can be

slipped and made fast in a few seconds, as compared with minutes when

the-wooden pack-saddle is employed. With the apparejo a train of eighty

animals can be loaded up with 16,000 pound?—approximately seven and a

half tons—of goods in lefts time than thirty animals, equipped with the

wooden saddle, can be got under way with 6.000 pounds.

At the present time.

owing to railway-building activity m Western Canada, the packer is

reaping a rich harvest. The survey parties must bo kept supplied with

provisions and equipment, and pack-trains are continually passing from

supply bases to the caches with necessaries. As a rule, the railway

companies acquire their own animals, disposing of them when the task is

finished, and hiring the men. The average wage is about £10 per month,

with everything found, and as the personal expenses are trifling and the

employment steady and continuous, a thrifty man can rely upon saving

£100 per annum without any effort.

The rapidity with which

the far North-West is being settled provides the packer with unique

opportunities to make money quickly. The enormous fertile tract known a3

the Peace River Country is attracting the more hardy farmers by

hundreds, and, although it is several hundred miles from the Grand Trunk

Railway, a steady stream of prairie schooners, teams, and other vehicles

are pouring northwards from a variety of points between Edmonton and

Edson. La Grande Prairie alone attracted 4l)0 settlers in the course of

a single season, although this little patch, 65 miles in length by 25

miles in width, of excellent open land and rich soil, is 350 miles as

the crow flies from Edmonton. Mineral searching activity among tho Rocky

Mountains has been responsible for the despatch of dozens of pack

trains, some with provisions, and others with personal impedimenta for

mining engineers.

In New British Columbia

the packer is having a busy time, and this will prevail for many years

to come. The pack-trains meet the railway at Ashcroft, or at Quesnel,

the Hudson Bay post 315 miles farther north, and radiate to all points

of the coir pass, stretching out as far as Hazleton, 420 miles beyond.

Others are now using the latter point as a has", and from there are

ploughing through the Kispiox Valley towards the province of Mackenzie

on the one hand, and Alberta, via the Peace River, on the other. Many

years will elapse before this vast tract of territory will be girdled

with the grey band of the railway, so the packer is not in immediate

danger of being driven from this promising country.

But the energetic young

fellow who realizes that Canada is a country where the maxim “ Get on or

get left ” is fought to the bitter end, is not content to remain a mere

cog in the machine which drives the train through the bush day after

day. He takes up the lowest position as a means to an end, and if he is

thrifty and careful, he soon reaches the height of the packer’s

ambition—he be comes the owner of a train. When first he strikes a trail

without a dollar in his pocket, he earns six, eight or more shillings a

day steadily. Then he realizes the fact that money can be made more

easily and quickly by letting someone else attend to the horseflesh on

the expedition than to be in that position himself.

It is not so difficult

a task to blossom into a master packer. The first season’s work should

lay the foundations for the venture. The cost of the ponies is not

heavy, ranging on the average from £6 to £10 apiece, if astuteness is

displayed when investing. Many private parties, instead of chartering a

train of animals buy the animals outright for their purpose as it is a

cheaper method if one is likely to pass many months in the wilds. When

these parties return, they have no further use for the animals, so they

sell them for what they will fetch; as they have recouped their initial

outlay in the bush. In the autumn, as a rule, prices rule low, because

buyers are few and far between, owing to the prospect of the winter’s

keep. Indeed, I have seen great difficulty experienced in getting rid of

horses at any price at the close of the autumn. Likely buyers shrug

their shoulders, point to the bright snow-caps cn the mountains, and

walk away. On the other hand, in the early spring buying is brisk and

fancy prices prevail. At one or two points, to my own knowledge animals

that would be difficult to change for a five-pound note in the late

autumn have fetched £20 apiece in the spring.

The sharp individual,

anxious to become a horse-owner, who has been packing all the summer,,

accordingly invests his money in horseflesh at the approach of winter.

The chances are a hundred to one. if the animals are suitable, that they

can find sufficient employment during the period when the Ice King rules

over the land to earn their upkeep by freighting with sleighs.

As the disappearance of

the snow heralds the packing season, the call for the pack-train

develops. No difficulty is experienced in letting out the animals on

hire at 4s. per day per head. If the owner is energetic and

enterprising, ho will take up his stand near the rail-head, from which

point the pack-trains push out during the season, this point being the

base of supplies. Then he can confidently look forward to a revenue of

£30 to £40 from each of his animals by the end of the season. During the

summer the animals do not cost him a cent. They graze in the open when

on the trail, picking up what sustenance they can obtain, and those who

have hired the train are responsible for the welfare of the creatures.

Should an accident befall an animal, then the hirer has to recompense

the owner, as the former takes all risks.

One owner I know

started in quite a small w ay. When he hit the trail for the first,

time, his knowledge of the craft was small but he soon mastered its

intricacies. By bargaining he exchanged the greater part of his season’s

wages for half a dozen sturdy animals, and, by keeping them going at odd

jobs during the winter, he contrived to make them self-supporting,

while, as ho always accompanied them himself, he increased his banking

account steadily. And by the time the spring came round ho had a train

of ten horses in the pink of condition. With this outfit he could

undertake small contracts, which he was able to manage unaided. When he

was chartered for bigger undertakings, requiring additional animals, he

made terms with other packers who owned one or two horses on the basis

of about 3s. 0d. a day per horse, or 10s. 0d. per day for the man and

his two animals. On the other hand, he charged his clients 4s. 0d. per

day per animal, and 8s. 0d. for the packer, so out of this transaction

he made a matter of 4s. 0d. per clay. In this manner he increased his

possessions until he owned about sixty animals, which were adequate for

his purpose. He admitted to mo that he could look forward confidently to

an income of £3 a day from his animals for a clear eight months during

the year. There were no expenses during this period of any description,

except perhaps for saddles, bridles, blankets, and such like, but this

was a trivial expenditure. During the winter they brought him in £1 per

day, on the average, so that his annual income was about £500 clear. The

only period when they were not earning anything was for about two

months, when they had to be fed at the rate of about £2 per head per

month.

One year he had a good

stroke of fortune. Thirty animals were chartered by a private party.

They went off at the beginning of March, and were not seen again until

November, putting in eight months’ continuous service on the trail.

Having been let at the usual figure of 4s. 0d. per day per head, this

contract brought him in a round £1,200. Such a sum is not clear od every

day, but at the same time it is not a rare occurrence. Another party

paid him over £000 for the use of a pack-train for three months, in

which case, as ho had to hire several horses to make up the train, his

net return was about £350.

Of course, the man with

capital, 'who can start operations right away as a master packer, stands

in a stronger position. He can obtain first-class animals by paying a

high price, and with a stroke of luck can look forward to a certain 30

per cent, return upon his outlay, even when allowing 33½ per cent,

depreciation per animal per annum, and assessing five months’ inactivity

when feeding averages £2 per month per head. As a matter of fact, there

are very few packers who will admit that money is made at this branch of

human activity, for the simple reason that so fast as they make money

they spend it. One packer, a young English fellow who had cleared a good

sum as the result of his summer’s operations and who decided to spend

the Christmas in England, started off from British Columbia homeward

bound. Before he reached Montreal he was poorer by £500, which he lost

by gambling on his way across the continent. This is the spirit of the

country. The man works hard and long to make money, and then enjoys

himself just as strenuously.

A first-class

pack-train, however, is a valuable acquisition. It is desirable that the

string of animals should be kept as intact as possible, because the

brutes soon shako down to their work, chum-up into small parties, whik1.

each learns his position in the train and, what is more, holds it

against all comers. If an animal tries to change its place in the

procession, lively times ensue. Without the slightest warning the other

beasts turn upon the usurper, let fly with their hoofs, and their teeth,

make wild rushes, and drive it into its ordained position in the train.

This peculiarity is perhaps manifested to the greatest degree in regard

to the leader. Ho sticks to the bell-boy tightly, and woo betide the

horse that tries to deprive him of his position. There ie a spirited

fight, and no little dexterity is demanded on the part of the packers to

restore order, for the leader refuses to bo deposed, and spares no

effort to retain his place of honour.

Probably the Diamond

Ranch train, the fame of which ha>i spread from Los Angeles to the

Klondyke, is the finest string of pack animals on the Pacific seaboard.

It is owned by a prosperous rancher of the Bulkley Valley, Mr. Barrett,

and he has certainly brought it to a high pitch of efficiency. For years

this train was engaged in the annual transportation of provisions along

the far-flung-out chain of cabins housing the operators of the Yukon

telegraph, which links up the Klondyke with London at Ashcroft. This

train comprises about 100 animals, the finest specimens of pack-horses

and mules it is possible to find. The horses arc laden with 200 pounds

apiece, while the mule’s load is from 250 to 300 pounds, as this animal

is the stronger of the two. The telegraph cabins are about thirty miles

apart, and each operator has his stores replenished once a year with

about 6 000 pounds of provisions of every description.

The trail lies through

the length of the country to Hazleton, an d the train starts out in

early spring from the south, distributing the provisions to a point

about halfway between the two extreme terminals of the line. Raaching

Hazleton, it loads up once more and pushes on to Cabin 9. about 185

mile-3 northl tho trail laying through very heavy and mountainous

country, and then retraces its footsteps to Hazleton empty. The whole

undertaking occupies roughly seven months. There is no need to proceed

farther north than Cahin 9, as the posts beyond to Dawson City are

supplied from other points, and are accessible for the most part by

water. In fact, it would be impossible to proceed farther north than

this point, as the season is well advanced by the time it is reached.

Often the pack-train is hastened south by the approach of snow, and,

indeed, it is not uncommon for it to make its way over the bleak Skeena

Mountains through the first white fleece of winter.

When camp is pitched,

the beasts range up side by side in a semicircle. The pack is removed

and piled immediately before the animal, with its apparejo alongside.

The animals are then turned loose in the usual manner to browse in the

bush. In the morning the packers are out early, rounding up the

creatures, and they tear into camp at a brisk gallop. As they come in,

each animal takes up its position before its pack, and if one should

assume the wrong position, he is soon corrected by the teeth and hoofs

of his comrades. There is no need for the packers to stir a hand to

guide them; they do it by instinct. Even if a disagreement breaks out

among the b rates as to a relative position, the packers do not

interfere beyond the ejaculation of a few stentorian curses. Peace does

not prevail until the interloper has withdrawn or has been ejected, and

has assumed his correct place in the line. The apparejos are hastily

placed in position the packs slung, and as fast as this task is

completed the horse drops out and loiters about, until the bell-boy

starts off, when it takes up its place in the procession. One often

marvels at the instinct of horses at a circus, but the true sagacity of

the animal is exemplified most strikingly when a pack-train is preparing

to strike the trail.

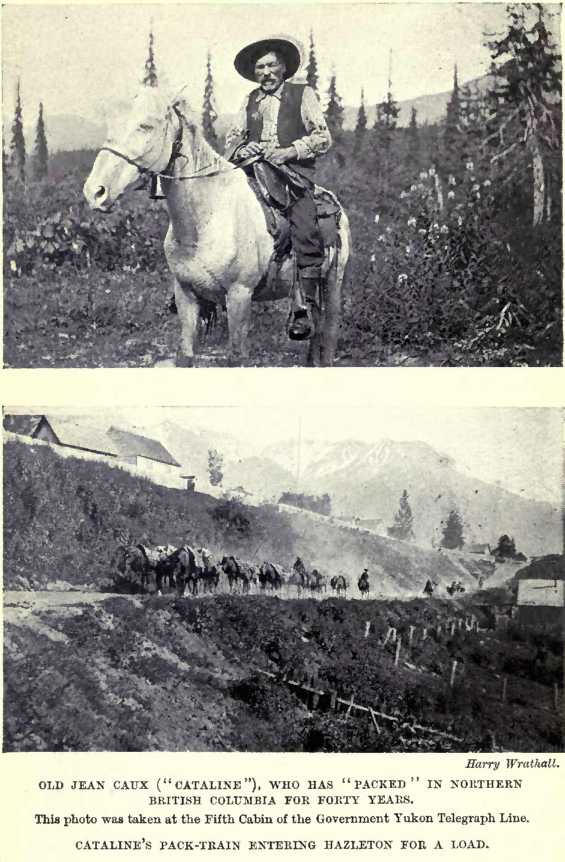

Another well known

packing character in British Columbia is old Jean Caux “Cataline” and

his train. He, likewise, is famous up and down the Pacific coast, and it

was over forty years ago that he pushed his way with his train from San

Francisco through Oregon and Washington into British Columbia, where ho

has stayed, tracking to and fro, ever since. Cataline is a character

such as is seldom seen. lie tells you that he was raised in Catalonia

and as “Cataline” is more tripping than his patronymic, ho has been

dubbed Cataline, and as Cataline he will be known up and down the trail

till he hands in his checks. When I saw him at Hazleton, one could

scarcely believe that he was seventy years of age. He was as upright, as

alert, and as athletic, as a city man a third of his age, a result due

to the trail and the lifelong tracking through the wilds. He spurned the

elements completely. Whether it rained a& if promising a second deluge,

snowed, or the sun blazed down pitilessly from the blue canopy, it was

all the same to him. He was out and about in his shirtsleeves, wearing a

hat that was now possibly a decade or two ago, giving orders and

slinging 100-pound packs about as if they were ounce weights. Nothing

escaped his vigilance. Most of his packers were Chinamen, selected

partly because they were cheaper labour, but mere particularly on

account of their reliability, steadiness, industry, and a natural

bred-and-born capacity to stand roughing it under the worst condition's.

They differed from the white pecker insomuoh as they did not haunt the

saloons from morning to night, when one was in sight; but they had one

pecadillo, and that was gambling. They would sit fer hours playing faro,

blackjack, poker, or any other game of chance, preserving absolute

equilibrium under the varying changes of good and bad fortune, but

invariably stripping the pockets of the white packers.

On the trail they work

more like machines than human beings. Now and again there would be an

upset at Calalmo disagreed with some operation they were performing, and

then a -vociferous hubbub would reign for a few seconds, Cataline’s

excited Spanish blood rising to such a degree as to cause him to drop

his broken English and to let fly violent invective in his

mother-tongue. The “chink” would retaliate in his own jargon, and the

confusion of tongues at Babel could not have been more jarring than a

squabble between Cataline and his packers, especially when one of the

Canadian comrades joined in, and vociferously urged each wordy combatant

to greater effort. The amusing part is that neither understands what the

other is saying, so probably no harm is done.

Cataline’s methods are

in keeping with his character. He sits down to his humble fare in the

open air, talking excitedly meanwhile, and at night he disdains tent,

fly, or any other covering or convenience for his couch. He pulls out

one or two horse blankets, spreads them on the ground, tucks an apparejo

under one end to form a pillow, crawls in, and is soon sound asleep

under the starlit sky. Often when he awakes in the morning his beard is

soddened with dew, rain, or decorated with icicles, as the case may be,

according to the vagaries of the weather, but such trifles pass

unheeded. When the pack-train moves off. he gives a spring which would

startle many a younger man, and is astride his tall saddle-horse,

shouting stentorian orders, as upright as a lath, and as quick as a

bushranger. Then he falls into the rear of the train and plods along

musingly, shouting some greeting to everyone he meets. When Cataline is

worried, one never guesses the fact, as he reveals no eight of his

thoughts upon his inscrutable face. He accepts delays and hindrances

more or less in the spirit of the Land of To-morrow.

When I met him at

Hazleton, he was killing time. He had just come in from Cabin 9, as he

had won the contract for delivering the provisions along the Yukon

telegraph line. He was fretting to return south, as winter was

approaching. Ho had no wish to fee caught on the southward jaunt by the

icy grip of old Boreas with his fleecy mantle, for there were horses

worth £2,000 at stake. But he could not go south yet. The Hudson Bay

Company had 12,000 pounds of assorted articles to be taken through the

Babine Mountains to the trading-post, thirty-six miles east. It was not

a long journey as trails go, but it was one of exceptional arduousness,

as the path lay over the mountains and across the watershed feeding the

Skeena River on the northern, and Babine Lake on the southern, side.

Furthermore, it was treacherous going, as the trail was littered with

rock, dead, fallen wood, and mud-holes, so that less than twelve miles a

day could be notched. Five days out and five days back was the schedule,

and it could not be curtailed safely with the load he had aboard.

There was good reason

for Cataline’s anxiety. According to the riddle of the trail, it was not

safe to attempt to reach the Babine post from Hazleton after September

15, and here it was two days over the limit. Every morning Cataline,

when he rose from his open-air couch, cast his eyes anxiously toward the

Skeena Mountains to see if further snow had fallen during the night. I

had come up from the south, and, having passed within sight of the

Babine Range, he inquired if I had seen any new snow down yet.

Considering that a few days before we had been caught in a light

snowstorm in the valley, it wa3 not surprising that the white mantle was

travelling lower and lower from the peaks down the mountain slopes,

while its brilliant -whiteness testified to the fact that it was a

recent garb. Cataline. five tons odd of freight were among the worst to

be handled by a pa retrain at that time of the year. There were

cooking-ranges packed in ungainly sections, piles of soft goods, pots

and pans, as well as foodstuffs of all descriptions. He had been held up

because some of his horses Lad wandered off in the bush. The Chinamen

searched from morning to night for three days, but found no trace of the

wanderers. At last the old packer could wait no longer. He pushed off

with the animals he had rounded up, and left one of the packers behind,

with strict injunctions to find the missing beasts at all hazards, and

to have them to Land by the time he returned, ten days later, so that

they could push south without further delay. The Indians were urged to

participate in the search by the offer of rewards, and the opinion was

ventured among the white men of Hazleton that so soon as Cataline was

clear of the town the missing animals would be found, as the Indian is

expert in corralling pack-horses in the expectancy of a remuneration.

When the dollars are put up, it is astonishing Low quickly lost animals

can be restored.

As may be supposed, a

packer like Cataline, who Las been knocking about the wildest wilderness

for close upon half a century, can relate stories of the trials and

tribulations of the task very vividly. He had a tough tussle to get into

the Babines one year. lie was late in starting, and about halfway on the

outward journey, where the rock is the most slippery, and the road the

steepest and most broken, a blizzard burst upon him. For two days the

train struggled with this implacable enemy, plunging blindly forward,

the men unable to see farther than a pack-horse ahead. It was no use to

camp in the Lope that the blizzard would lift up, as there was the

danger of being snowed in, and the post was waiting for the goods

strapped to the animals backs. By toiling along afoot, guiding the

horses as best they could, suffering many falls and bruises against the

obstacles littering the trail, they emerged from the snow zone on to the

lower levels, and gained the post in safety.

The outlook was far

from alluring. The pack-train had to make Hazleton again, and then had a

dreary 420-mile drag southwards. There was every indication that winter

was arriving before its usual time. The question was: Could they race

the snow to the south? Cataline determined to make a si niggle to that

end, at all events. Directly the packs were stripped, the train retraced

its tracks. All went well for the first, two days, when, as they were

crawling over the summit of the watershed, the Snow King swept down once

more with greater fury, as if bent upon the destruction of the little

band. The horses were scattered, and the men could not distinguish the

equine forms from brush, owing to the whirling, skirling flakes. For

forty-eight hours the packers fought the storm, never resting a minute

for food. Their one thought was the safety of the animals, and the

resistance of the humans was equal to the ferocity of the attacks of the

allied forces of the Snow King and Boreas. Their pluck was rewarded. The

blizzard, as if defeated, held up, and the pack-train strugglod into the

town.

Cataline realized that

he had a desperate 420 miles in front of liim, but, as he had weathered

many a disaster in the wilds. he determined to make the risky journey.

With all speed the horses were packed, and they struck the homeward run

with grim determination. It was a desperate race against the elements.

But the latter were wily. They held off until the pack-train had got a

good start, and then bore down with fiendish virulence. Cataline rallied

his forces, and the packers, to a man infected with his determination,

resolved to drive the horses through. They fought the blinding snow for

hour after hour, and then lost the trail. The hardy old packer, though

still infused with plenty of fight, recognized the hopelessness of his

position. Drifts were ahead which were deep enough to engulf both men

and beast, the trail was obliterated, the cold was intense, and, though

they might blunder on, the chances were that they would strike a blind

steer, as the cul-de-sac in the forests is called. lie summoned his

fleetest saddle-horse and packer. “Ride back and say that there is no

chance of our getting through with our packs.”

The rider tore off,

fighting his way foot by foot through the billows of mow which strewed

his path. Ho rode into the post with his horse steaming, and related how

the pack-train was stalled and in jeopardy. There was no alternative.

The train muse return, and those waiting for the goods on the horses’

backs must go without. The rider sped back through the piling drift, and

Cataline, marshalling his pack together, with great difficulty returned

to the town. It was a sore retreat to him; 17,000 pounds of freight were

astride the backs of his train. This represented a solid £130 in cash.

But it was not worth while to risk the safety of the animals for this

sum of money. So he jogged into the town rather disconsolately, his

train knocked about sadly, and shed the precious cargo. Then he turned

his course southwards once more. Now that his animals were travelling

light he cared little for the elements. They were overwhelmed with

blizzards, but they drove their way through, and, somewhat emaciated and

weary, the beasts made the home port safely. The pack-train was safe,

but its owner was poorer by over £100. Such a loss in the pack-train

business is not to be made up again very easily.

The first year Cataline

took over the Yukon telegraph supply contract adversity hit him hard,

and he came oif somewhat badly in the encounter. That is the worst of

Fortune in the wilds : she hits with au iron list, and every blow gets

home. Hia animals were laden to their utmost capacity. The Government

had undertaken to clear the way for Lis team, but the winter had been

hard and spiteful. The creeks were high with the melting snows, and the

fierce torrents had carried away the slender timber bridges. Added to

this, the wind and snows had brought down trees by the hundred, and the

trail was a hopeless tangle of trunks Every lime a bubbling waterway was

met time bad to be wasted in repairing the bridges, and just how much

Cataline spent in this connection no one knows. The Government were

quite prepared to dispense £600 in fixing the trail to facilitate his

advance, but the clearers were late. At one point Cataline’s pack-train

was held up for a solid fortnight, his packers working like Trojans to

repair a rough log bridge that bad been smashed to smithereens by the

raging waters. And in a country where the transport season lasts only

about eight months a fortnight is a substantial loss. As the old packer

related, it was a stem battle every mile of the way, but he gave a grim

smile as he added: “Yet we got through.” That is the packer’s manner. He

may be up against it the whole time, but he is only concerned with

getting to his destination, which, when reached, provokes chuckles and

laughter concerning the trials met on the way.

Cataline has achieved

some smart packing performances in his time. On one occasion he packed

18,000 pounds of flour a matter cf 250 miles, and transporting some tons

in this manner is no light achievement. On another occasion he carried

12,000 pounds of mixed goods of all descriptions, many articles bulky

and awkward to stow on a mule’s back, over a similar distance.

Considering that the load per animal varies from 250 to 350 pounds,

according as to whether the animal is a horse or mule, this performance

is by no means to be disdained.

Such is the packer’s

life. He is one of the heroes of the wilds, keeping the isolated

communities going by hook or by crook. He deserves every penny he earns.

But the life has a peculiar fascination, and so long as new territories

in Canada are opened up, so long will the packer continue to ply his

adventurous and exciting calling.

|