|

Notwithstanding that

the pack-horse is indispensable, the moment a wide road is driven

through the bush, the packer is superseded by his heavier and bulkier

rival, the freighter. He is practically the carrier of the wilds. In the

past he has been eminently successful in Western Canada. His position

has been somewhat autocratic, his charges high, and his work tolerably

easy. To-day he is suffering from bitter competition, the day is bard

and long, and the prices for the most part rate low, except in the more

remote outlying places.

In the good old

Canadian days, when animals for haulage were scarce, the demand for

waggons was greater than the supply. Accordingly, rising communities in

the bush were entirely at the mercy of the freighter, and provisions

were forced to famine prices owing to his extortionate methods. It cost

more to defray the carriage on articles than their actual value;

foodstuffs were from 300 to 500 per cent, above the prevailing prices in

the cities.

At that time freight

rates ran up to as much as fifteen pence per pound. This seems a

prohibitive figure, but there was no method of bringing about a relief.

Ao the country became more and more settled, the established freighters

found that they were in danger of being undermined by independent units.

Enterprising individuals, realizing the high profits to be made out of

freighting, unostentatiously acquired a team of horses or oxen and a

freight waggon, and, being their own masters, applied for custom by the

simple expedient of cutting prices. The established freighters at first

were disposed to laugh at this effort to deprive them of their traffic.

They had excellent contracts, and the individual freighters were at

liberty to pick up what they could here and there, which crumbs were

thought to be so scarce as to be insufficient to keep a chipmunk alive.

However, the master

freighters received a rude shock as their contracts expired. Their

clients displayed no keen desire to renew them on the old terms. B was

prepared to carry the goods cheaper, so why could not A ? Once the

toppling over of prices commenced, it continued with a run. The number

of individual freighters increased alarmingly, until at last freight

rates reached a level which was absolutely unremunerative except to the

man who only owned a single team and waggon. The freighter who was

content to lounge around the saloon, smoking his cigars, while he paid

labour to carry out his work disappeared in the upheaval, and his demise

passed un mourned.

The competition,

however, has not eased in the slightest. The prosperity of the country,

the extent of railway building operations, the opening up of new

territories, the foundation of new towns at the rate of two or three per

week, has developed a healthy, energetic race of teamsters and

freighters. Many recall the old times with a sad shake of the head, but

they have no time for lamentations, inasmuch as the pace is hot, owing

to the more agile, shrewder, and enterprising young men who are entering

the field, probably only for a time, to enable them to obtain a

financial foothold for other occupations. These tactics, however,

shatter the hopes of the old, grizzled, weather-beaten warriors of the

up-country road, that good times will come back.

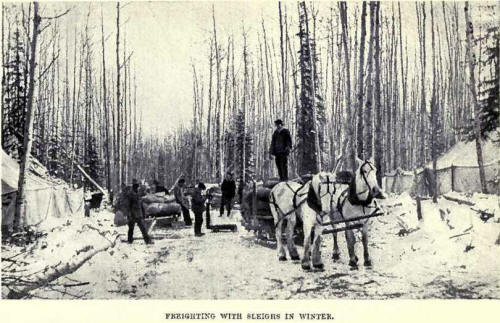

The- freighter’s

stock-in-trade is by no means pretentious. A couple of good, strong

horses or oxen and a substantial waggon will give him a good start. His

capital need not be extensive, as his animals require little fodder

during the months when the ground is green. He will require the

assistance of another pair of hands, and in order to get the utmost from

this system two kindred hard-working spirits will often co-operate. A

supply of provisions must be laid in to carry them over their journey,

with perhaps a bale or two of hay for their stock in case of

emergencies, but that is about all.

The most promising

field of activity for general freighting is in the vicinity of

railway-building operations, such as, for instance, the cons! ruction of

the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. The contractors attack the undertaking

from a hundred or so points at once, scattering their camps about two

miles apart, and driving the grade right and left from these points

simultaneously until the respective links meet and are joined up.

These camps may stretch

over a distance of 100 or 150 miles ahead of the end of steel, as the

temporary limit of the locomotive’s advance is called. Consequently

every ounce of material for feeding and clothing the men, as well as for

building the lines, has to be sent in by road.

This is the freighter’s

opportunity. A rate is fixed for the conveyance of all material from the

end of steel to the camps or building sites ahead. The rate may be so

much per load in the case of bulky constructional material like baulks

of timber; or with varied assorted articles, such as foodstuffs and

other necessities, it is so much per pound, the terms varying according

to the distance to be traversed. In one particular case the supplies had

to be shipped in by waggon for 107 miles, and the rate was 10 cents, or

roughly 5d., per pound. By averaging about fifteen miles per day, the

teamster could cover the journey, if the fates were kind, in a week; but

then he had an empty jaunt back, so that the fortnight’s expedition was

not particularly profitable. Yet by working bard, and keeping on the

trail from the first streaks of dawn to the longest shadows of dark, he

might scrape out £6 per week, from which he had to deduct his expenses

for provisions on the way.

So far as the round

trip rate is concerned, this is about equal in its profitable results. A

lofty timber trestle was being erected for the railway twenty-two miles

beyond the railhead, and all pressure was being centred upon this work,

so that it might be completed by the time the nose of steel had crept

forward with its locomotive and trains to that point. The timber baulks

were massive pieces of lumber cut from the tallest forests of British

Columbia, many running up to 60 feet in length. Some of the waggons were

able to carry two baulks at a time ; others h&d to be content with one,

owing to its length and weight. The price paid for hauling m the load

from the end of steel to the site of erection was £3. For this sum the

teamster had got to drive forty-four miles, the homeward journey being

made empty. If the roads were in a clean condition and the weather kept

fine, the round trip could be made under three days, so the freighter

could get in two, or at a tight squeeze three, loads per week. One

hurtling young teamster supplied me with the information that he was

charing up £1 per week clear. This entailed working practically sixteen

out of the twenty-four hours, required a first-class assistant, fine

powerful horses, a. good waggon, and an aptitude for getting through the

mud-holes with which the road abounded.

I had one taste of

freighting. Material was being rushed ahead for the Rocky Mountains

section of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. The waggon was a ricketty

structure, sitting on four wheels. A couple of excellent horses were

hitched to the shafts, and they seemed to possess enough strength to

pull the waggon in twain. Still, the fabric kept together, although I

have half an impression that this was due to the baulks of timber aboard

being lashed, so tightly to the respective axles, that the tatter could

not very well fall apart. The teamster was a young fellow from London,

who had been associated with the horse-omnibus, or some other duty which

brought him into touch with horses, and for which he had received the

scarcely handsome salary of some 25s. per week. Realizing that the fate

of the metropolitan horse was sealed by the motor vehicle, he had wisely

refrained from trying to seek another job in the Great City, and with

his little savings he had taken a steerage passage to Canada, and landed

with the proverbial immigration allowance in his pocket. lie had drifted

farther and farther west, until he had run up against the railway const

motion armies. He got a job at once at 8s. a day all found, at freight

ing, and soon learned the ropes of the game. His knowledge of horses

stood him somewhat in good stead, and the character of the work,

affording no time to thirk or to get home-sick, appealed to him. As he

tersely put it, “When yer wann’t drivin’ yer was sleepin’, and when yer

wasn’t sleepin’ yer was drivin’, and when yer wasn’t doin’ neither, yer

was up to the waist in muskeg, givin’ the horses a lift at the wheel

with yer shoulder.”

His life was typical of

the freighters, whether you find them on the reilw-ay grade, in the east

or the west of the country. Sunday was as a blank day. It gave the

horses a much needed rest, allowed the teamster to sleep off the balance

of hours necessary to keep the human engine going, which he had lost in

the previous six days’ toil. The train came in with its letters. He had

the only chance in the week to write home, could complete his laundry

operations, darn and mend, wash and brush up, and change his

underclothing, these latter tanks being intended to last round till the

following Sunday, as the clothes were not taken off during the ensuing

week. If the waggon required any repairs, this was the time to do it,

unless he wanted to lose some precious hours and dollars on the road. By

the time these various duties were completed, darkness had fallen, and

it was time to turn into the bunk, likewise for the lest occasion until

the following Sunday came round, to get another good rest before

commencing a grinding week.

By six o’clock on the

Monday morning the waggon commenced its rush over the road with a fifty

foot stick of timber aboard. But it was not a case of sitting up on the

driving-seat with the reins Wangling idly in the hands and the head

nodding while the hordes ambled along at a snail’s pace. Every

succeeding minute brought a variation ; the development of something

unexpected. Constant vigilance was demanded. A moment’s lapse and the

wandering mind was brought back to the backwoods by the rear wheel

dropping with a wicked lurch and squelch into a four-foot mud-hole, and

nearly throwing him over the side to stick upright head-first in the

mud.

With a hop he was off

the waggon, and the next moment three feet of him were visible above the

viscid, evil-looking water. The horses were kicking and plunging,

warping the vehicle to and fro, and only causing it to sink deeper. He

waded round the almost submerged wheel, summed up the situation in a few

seconds, and then waded out of the mud-hole, catching hold of his axe as

he passed the waggon. The next minute he was making the white chips fly

as he swung his tool with rapidly measured strokes against the trunks of

some jack pines by the wayside, pulled them over to the mud-hole, and

laid them in front of the stranded wheel. Half an hour sped by in this

work, the horses meanwhile standing still. Then, prising his feet

against one of the buried logs, he bent his back like a bow, and as he

yelled out “Git up!” he pulled desperately at the wheel. It moved slowly

but steadily. A tree-log rolled beneath it. Catching something firm to

grip, the wheel flew out of the mud-hole, smothering the teamster from

head to foot. The horses stampeded out of the morass, and when they

regained dry land, stood shivering and snorting after their exertion.

The teamster floundered

out in their wake, the mud streaming from his waist in a black trail

along the ground. Out came a spanner, and soon the wheel cap was lying

on the road, while a bunch of grass was cleaning out the mud from the

bearing. A blob of equally black grease was jerked in, the axle cap was

replaced, the teamster clambered aboard, and once more was jogging

along, the mud on his clothes either drying in the sun or being washed

off by the rain, according to the mood of the elements.

Mile after mile this

round continued. By keeping a sharp eye on the road surface, some of the

obstacles could be avoided. Wherever an innocent puddle of water

stretched across the highway, the teamster gave his horses a turn with

the rein, and urged them to a spring so as to dash headlong through the

bush. The vehicle swept sideways, the heavy load aboard giving the

crazy-locking vehicle sufficient impetus to tear up and break off young

jack pines, and to carry away scrub by the roots. When the bad spot was

passed, the vehicle reeled out on to the road again, and a smart lookout

was kept for the next trial. It was of no avail anticipating any

particular obstacle, because the unexpected lurked everywhere. The

fussing creek appeared as easy to cross a3 a macadam roadway. Only 2 or

3 inches of water babbled over its pebbly bed. With a whoop the waggon

went flying down the declivity, all on board stiffening the limbs to

secure a firm hold. The horses dropped into the water, and the waggon

made a bounce of 2 or 3 feet, coming down with a tremendous crash and a

splash. You expected a healthy jar as the wheels hit the bottom and gave

a smart rebound, or the collapse of a wheel under the strain; but

neither happened. Then you thought the wheels must have struck a

cushion, but looking over the side you could just see 3 inches of steel

rim gloaming above the churned-up water. Ihe horses kept pulling, and

the weight aboard kept the vehicle lumbering forward, so that the

efforts of the animals enabled the unwieldy mass to gain the opposite

bank. Then it stopped ; on dry land it was true, but stalled as

completely as if buried in mud. The acclivity was too steep for the

horses. Off jumped the teamster, a coil of rope in his hand. He fixed

one end to the front of the vehicle, and climbing up the bank, set rope

and tackle to a tree stump in the twinkling of an eye.

“Now then, boys!” We

all gripped the end of the rope, the horses were urged to supreme

effort, and while they lugged and strained, we stuck our heels into the

ground and hauled for all we were worth. It came up inches by inches, a

breather being taken with every slight advance, until at last, when on

the brow, we yanked her over. The best part of an hour was gone in

making 50 yards, and that could not be considered a furious pace.

It was a good

opportunity to have a little lunch. The horses were uncoupled and turned

adrift in the bush to get something to eat. A firo was lighted quickly,

water was soon boiling, and a steaming cup of tea was so irresistibly

fascinating, that they break away from civilization for a time, and

wander around the scenes of their former struggles fraternizing round

the camp fires and exchanging stories with the new men in the fields

where they won their spurs.

Yet freighting is not

entirely the dog’s life that it seems upon the railway grade. That

reveals the calling m its most forceful phase. The other side of the

picture is revealed on such journeys as the Peace River trek, the

discovery of the gold mines around Porcupine in Ontario, on the Cariboo

Road in British Columbia , or way down among the spurs being driven by

the Canadian Pacific Railway. As the Grand Trunk Pacific approached New

British Columbia’s fertile plateau, settlers rushed into “ The New

Garden of Canada ” from all parts. The great highway was from Ashcroft

on the Canadian Pacific Railway northwards to a point known as Soda

Creek on the Fraser River, or to Quesnel. From the latter point extends

an excellent frontier road following the Yukon telegraph line. Soda

Creek is the point whence the steamboats run up the Fraser River to Fort

George, as well as the higher reaches of the Nechaco and Stuart Rivers.

Directly the country was opened, an important town was created at Fort

George. Alt hough the nearest railway-station was 318 miles to the

south, people rushed northwards by the hundred, many falling foul of the

hopeless transportation conections at the time, to return southwards,

wiser in knowledge, but poorer in pocket.

Everything from food to

clothes, tools to materials, and general supplies, had to be brought up

overland, and the result was that no one could live in Fort George

unless he had. savings or the means of existence. Flour cost more in

Fort George than it did in Dawson City. To transport this commodity from

Ashcroft to the budding metropolis cost 2½d. per pound.

This was the round day

after day, for six days in the week, with no longer pauses t han were

absolutely necessary. When the destination was gained, the weighty baulk

was whisked o££ the waggon by a derrick, the teamed head was turned, and

all were on back again for another load.

I asked this hustling

young Londoner how long lie thought he would keep up this pace?

“Well, I’ll be going

out next year. By then I reckon I’ll have got a solid hundred pounds

tucked away. I bought this outfit cheap from the fellow I was with. He

got sick of the game. I’ll do the same. Or I might take the beasts with

me. They are two fine pieces of horseflesh. What’ll I do? Heaven alone

knows! But I’ve heard that freighting is good up on the Peace River and

mebbee I’ll go up there for a change. I’d like to see that country.”

This is characteristic

of the new arrival in the West. He stays at one place until he is tired

of the scenery and surroundings, and then hies to pastures new. This is

his round of existence. Piajing football with fortune makes a peculiar

appeal, and it must be confessed that wandering from pillar to post in

this manner, picking up money all the time, offers an excellent

education. Sooner or later some place makes a strong call, and there the

wanderer settles down permanently, unless the restless feeling revives

temporarily, when the appeal is answered and a brief spell is taken in

the wilds just for old time’s sake. There are many people in Canada

to-day in comfortable circumstances in the cities, having earned a

contented position through the gold they struck in the Yukon, or the

money they made “mushing” through the wilds. Periodically the old malady

grips them, becoming so irresistibly fascinating, that they break away

from civilization for a time, and wander around the scenes of their

former struggles, fraternizing round the camp fires and exchanging

stories wi*h the new men in the fields where they won their spurs.

Yet freighting is not

entirely the deg’s life that it seems upon the railway grade. That

reveals the calling in its most forceful phase. The ether side of the

picture is revealed on such journeys as the Peace River trek, the

discovery of the gold mines around Porcupine in Ontario, on the Cariboo

Road in British Columbia, or way down among the spurs being driven by

the Canadian Pacific Railway. As the Grand Truck Pacific approached New

British Columbia’s fertile plateau, settlers rushed into “The New Garden

of Canada ” from all parts. The great highway was from Ashcroft on the

Canadian Pacific Railway northwards to a point known as Soda Creek on

the Fraser River, or to Quesnel. From the latter point extends an

excellent frontier road following the Yukon telegraph line. Soda Creek

is the point whence the steamboats run up the Fraser River to Fort

George, as well as the higher reaches of the Neehaco and Stuart Rivers.

Directly the country was opened, an important town was created at Fort

George. Although the nearest railway-station was 318 miles to the south,

people rushed northwards by the hundred, many sailing foul of the

hopeless transportation conditions at the time, to return southwards,

wiser in knowledge, but poorer in pocket.

Everything from food to

clothes, tools to materials, and general supplies, had to be brought up

overland, and the result was that no one could live in Fore George

unless he had savings or the means of existence. Flour cost more in Fort

George than it did in Dawson City. To transport this commodity from

Ashcroft to the budding metropolis cost 2-Jd. per pound. Oi this total

the steamboat claimed one penny for the journey between Soda Creek and

Fort George, but the freighters on the Cariboo Road received ljd. per

pound for carrying goods over 163 miles.

This road is

excellently built, and taken on the whole, the freighter life over this

highway is attractive and easy. At interval!! of about twenty miles are

well-built log houses and stables—stopping-places or bush “hotels”—

where an excellent meal can be obtained for 2s. per head, ranging

through four or five courses, with bunk sleeping accommodation for the

men, and good, stabling for the horses. The day’s journey is on the

average from one stopping-place to another. A freighting enterprise in

these days which brings in £14 per ton is not to be disdained in Canada,

especially under such first-class travelling conditions. The direct

route from Ashcroft to Soda Creek, while constituting the channel for

the bulk of the traffic, is only one point to which freight is conveyed.

The peoples of Quesnel and Barkorrille are entirely dependant upon the

freighter for their necessities, and he mulcts them 2d. and 3d. per

pound respectively, for the privilege of keeping them alive.

When the New British

Columbia boom set in two or three years ago, the freighters who had been

lamenting their bad straits in other parts of the country, flocked to

Ashcroft. Yet the invasion was not equal to the demand. A £it ring of

waggons laden to breaking-point sprawled out over the 163 miles to Soda

Creek, and another empty procession was drawn cmt in the reverse

direction. The two streams kept in movement like an endless conveyer

belt scooping up the loads at Ashcroft, and disgorging them at Soda

Creek. They travelled as hard as they could go, end yet the pioneers at

Fort George were condemned to short rations at times. The more energetic

freighters who had suffered nothing but losses or merely starvation

pittances out of their toil for years past in the middle west, made good

quickly or the Cariboo Road. They regained a near approach to their old

time autocracy and independence, since, when the railway company desired

its special requirements to be shipped in for the purpose of building

the line through the country, and there was every indication that long

and remunerative contracts could be obtained, the freighters resumed

their avarieicunness. The general rate must bo maintained, they argued.

The railway authorities demurred, and requested special quotations.

Seeing that some of the loads ranged individually up to 5 tons or more,

but; were capable of being handled easily on the well-built road, the

prospect of paying £40 for the transport of one article was somewhat

startling. The freighters condescended to carry out the work for £10 per

ton, but even this figure did nut appeal to the railway contractors, so

the matter was dropped. The requirements for the railway now are being

shipped in from the east over the completed line, and transferred direct

to steamboats on the Fraser River. The freighters have lost a golden

opportunity to reap a rich harvest through their greed, and the result

is that within a few months the traffic on the Cariboo Road will dwindle

to its straggling stream of five years ago. for freight will be landed

in Fort George at £2 per ton by rail and steamer as compared with the

rate of £14 now prevailing.

Other younger and more

enterprising freighters, realizing the situation, have pushed beyond the

Cariboo Road into the heart of the country, and are establishing

themselves firmly for the assistance of the incoming settlers, who are

certain to flock in when the railway is completed. One trader told me

that at the moment he was paying 5½d. per pound for all articles

discharged at his shop and brought up from Ashcroft. What this rate

means to the buyers, when investing in such necessary articles as sugar,

soda, eoap, and so forth, may be easily realized.

Yet, although the

freighter is being driven off the great highways of the bush by the

railway, the future is by no means gloomy. The energetic have the

opportunity to makR good far more easily, quickly, and effectively

to-day than yesterday. But they will have to accommodate themselves to

the conditions. The Government is driving good roads in all directions

to facilitate access to the remote areas. The freighter will have to

emerge from his chrysalis state with horse and. waggon into one

analogous to the British carrier so familiar in our rural districts.

Equipped with motor vehicles so as to cover the ground more quickly, he

will constitute an excellent feeder to the. railway with the certainty

of not travelling empty on one journey, but laden to his fullest

capacity both out and home. The traction freighter has not yet arrived

in Canada. His turn is coming, and the men who have sufficient go, a

headness to keep pace with the wheels of progress, and who will press

the commercial motor into service, arc those who will score success. |