|

The frontiersman on his

journey of discovery through the wilderness of virgin forest, makes his

way as best as he can. He has no compass ; very often lie has not even a

watch to serve as a makeshift to enable him to pick up his bearings. The

heavens constitute his sole guide. Axe or jack-knife in hand, he blazes

his way as he goes, so that if a retreat is compulsory by the appearance

of some difficult obstacle, he can retrace his footsteps fairly easily

and quickly. Otherwise his tracks are w<)lnigh indiscernible. He crashes

through the bush blindly, shielding his face from the whipping leashes

of branches with his armed hand, and the undergrowth closes up behind

him as waves engulf a wreck. To attempt to follow in his tracks is

wellnigh hopeless, as 1 have found from bitter experience. The blazes on

the trees at places are as thick as leaves in Summer, and they appear to

lead off to all points of the compass. You follow one blazing

laboriously, only to find that it is a blind lead to the brink of a

ravine. You retrace your footsteps, and, picking up another blazing,

trudge off in the opposite direction. That comes to a full stop beside

the wicked, impassable rapids of a skeltiring river. Back once more to

make a third attempt with the same fruitless results. You may have boxed

half the compass before you succeed in picking up the only trail leading

out of the difficulty, at the end of which time many miles have been

covered laboriously. Yet you have only wandered faithfully in the

footsteps of the frontiersman. He made every one of these abortive

journeys, with infinitely more difficulty than you following in his

wake, in search for a passage, and naturally blazed his way every time

from the central point.

Should that trail

become generally used subsequently, the man following it is saved

fruitless expeditions. The blind trails are blocked up by throwing trees

across them, or by forming a rude barricade of brush, while the true

path is blazed more prominently than ever. In course of time, the trail

becomes easier to read, as the signs on the trees are seconded by the

churned-up ground.

Yet the time that can

be lost over blind leads is amazing. Time after time, in making slow

progress through the forest, I have been lured away from the true path

by a promising side trail, and have only found out the mistake when

several miles have been covered to no purpose. The difficulty of picking

up a trail becomes somewhat intense when it leads down to the edge of a

wide, shallow stream. The bushes on the opposite bank press so closely

together, and kiss the water so unbrokenly as to reveal no sign of where

the track re-emerges from the creek. Should a path be seen to lead along

the bank, it is naturally taken only to come to an abrupt termination.

On one occasion no less than six hours were spent in trying to follow a

will-o’-the-wisp trail through a swamp. A trail ran through the morass,

and we followed it to find ourselves wandering round in circles, and

cutting other geometrical designs in 3 feet of stagnant water and

towering sugar-cane grass.

When the country beyond

has opened up, and tho speculators and settlers are surging resistlessly

towards the new magnet, a way must be carved through the silent dark

forest to facilitate their forward movement. First, it is merely a

trail, a narrow pathway cleared of trees, and with the brush cut back,

just wide enough to permit laden pack-horses to walk in Indian fils. So

far as the surface of the ground is concerned, the beasts must boat it

down with their own feet. When the trail lies over high ground, the

going is generally easy, but when it swings down into depressions and

dabs in which the water drains, then the feet of the creatures generally

succeed in churning the mass into quagmires and mud-holes, in which it

is not a difficult matter to sink up to the waist in the stickiest slime

found outside a liquid glue factory.

Cutting the trail is

the first task in the opening-up of a new territory. In the early days,

when the Hudson Bay Trading Company became established in the country,

they drove their own trails from post to post, and these have since

proved invaluable highways through territory in which the company

carries out its operations. But for every mile which this company has

driven through the wilderness, twenty miles of new trails have had to be

cut, and this, when there are no Indian tracks to assist in the

enterprise, is heart - rending work. The cutting gang generally

comprises devil-may-care young fellows, or sourdoughs willing to earn

from 8s. to 20s. or more a day, according to the situation ox the

country to be traversed. They sally out with a small pack-train laden

with provisions, tents, and other necessaries. Their tools comprise for

the most part axes, large jack-knives, with edges as keen as razors, and

coils of rope. As they advance somewhat quickly through the country,

they are lightly equipped to facilitate progress, provisions being sent

in periodically, and cached at frequent intervals, from which immediate

supplies are drawn as required.

It seems a simple

calling where there is no demand for any particular skill. This may be

the case, but, on the other hand, the work is hard, the life is

exceedingly rough, and there is always the risk of accident. The

majority of men who have taken one ium at trail-cutting generally make a

vow to avoid it in future, as the loneliness of the forest, the monotony

of the daily round, and the silence that can be felt, knocks all the

sense out of the tenderfoot. On the other hand, there are many

individuals who prefer this type of labour. It is out of doors, healthy,

and full of excitement, especially when the bush is well - filled with

game and there is the likelihood of meeting some spirited encounters

with bears. As a means of drilling the raw material into the ways of the

wilds, it would be difficult to excel. The tenderfoot is brought up

against it at every turn, and the difficulties, piling up on one another

with startling frequency, bring out the man’s temperament to an acute

degree. It gives him such a taste of the bush as to make or mar his

future in the West. If he goes under, he returns to the city with his

air-castles of romance and glory shattered like glass.

In British Columbia the

majority of the roads have been built from a gold rush. When the

wonderful news of rich strikes in the Cariboo country filtered through

in the ’sixties of the last century, gold-seekers, human vultures,

gamblers, and speculators pushed northwards. The prospect confronting

them was even worse than that in the Klondyke half a century later.

There were no railways in the e our try. The fever-stricken pushed their

wav up the Fraser River frc m Vancouver as far as Hop3 or Yale, and

there had to leave the waterway as the endless string of canyons loomed

directly ahead. From that point they had to proceed as best they could,

and how many went, under in the ordeal no one knows. They had to wind

along the brinks of the terrible, deep cracks in the mountains, through

which the river thunders, climbing up and down steep cliffs hand over

hand, in the manner ox the Indians, many slipping and breaking their

necks in the process. At last the Government came to the rescue. A

waggon road was built from Hope into the heart of the Cariboo country.

It was a gigantic undertaking, stretching for several hundred miles. The

grades were terrific, and at places the pathway way hewn out of the face

of the cliff a thousand feet above the foaming waters below. A slip over

the edge, and there was a straight headlong dive into the river. As one

rolls through those gorges in the cars of the Canadian Pacific Railway,

one may catch glimpses of this pioneer road perched on the' sky-line

above.

In a way this road was

useless expenditure, for shortly after it was completed, the gold strike

petered out, and the Cariboo became little more than a memory. During

the past few years, however, its last lap of 150 miles extending

northwards from Ashcroft on the Canadian Pacific Railway, has resumed a

touch of its former activity and bustle. The stage - coach, motor-car,

pack-horses, and freight waggons, jostle and hustle one another on its

surface from morning to night, because the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway

is being built through the heart of the country to the north, where the

wonderful agricultural riches of New British Columbia have been

revealed. Farmers, speculators, traders, and a host of other pioneering

spirits are burging forward to be in on the ground floor, disputing the

passage along the highway with the lumbering waggons taking in

provisions and necessities not only for the new railway, but also for

the numerous communities rising up like mushrooms throughout the length

and breadth of this wonderful mountain-locked, fertile plateau.

When Skookum Jim, the

Siwash, and his colleague, Dawson Charley, discovered the glorious

Klondyke, and the wealth of their discovery hypnotized the whole world,

causing hundreds of gold-eeekers from every country between the two

Poles to hurry to Skaguay, to reach the Bonanza, where gold was to be

picked merely for the stooping, as they thought in their mad delirium,

the thousands of early arrivals trailed over the Chilkoot Pass. The

ranks were so dense that the gold-seekers became a vibrating, heaving

mass of humanity standing out black, like an ugly gash, against the

white background of snow, packed so closely together as to tread almost

upon one another’s heels, and moving forward with mechanical precision

and slow, rhythmic speed. The trail was so narrow that two men could not

walk abreast, and if one dropped cut from exhaustion, those around him

could not pause to render aid, as they were pressed forward relentlessly

from behind. The speed of movement was governed by the pace of the

leading seekers. If they spurted forward, the whole line quickened its

pace ; if they lagged from fatigue, there was an accompanying diminution

in speed behind. The fresh spirits at the tail, fuming at the slow pace,

and anxious to press forward, had to curb their impetuosity. To venture

from the confines of the footprints -winding up over the Lump was to

court disaster ; to leave another batch of bones to bleach in the

following summer’s sun.

The law of the Klondyke

trail was harsh, but it is a country where kid glove methods were

impossible, especially in those days. Horses were prossed freely into

service, being purchased at prohibitive figures at Skaguay, and were

always laden to well above the “Plimsoll” mark of the trail. The animal

surged forward. They could not pause for a breather on the steepest

slopes, but had to keep going somehow. When a beast dropped down from

sheer exhaustion, it had to be got on its feet at once, or it was lost.

The line behind pulled up if it could, and the man was given just enough

time to slip the packs from his horse and no more. If he fumbled on the

task or took too long, he was swept cut of the way, and the procession

moved on. The chances were a thousand to one that the man who had fallen

never reached the Klondyke. The gold-seekers passed him without a

thought of pity, deaf to his entreaties, and blind to his struggles.

Sympathy was wasted. Those who pushed on while he writhed in the agonies

of death never know whether their turn might not come next. At one

point, where the trail was particularly wicked, and where the horses

fell down by the score, it wound round the edge of a fearful ravine. It

became s>o littered with the bones and corpses of the fallen animals,

that the spot received the lugubrious nickname of “Dead Horse Gulch,” by

which it is known to this day, and serves to recall the memories, the

excitement, the castles in the air, and the blasted hopes and miseries

of the Yukon fifteen years ago.

When the rush was at

its height, CaptainMcore, an old pioneer who had navigated the waters of

the Stickine for more years than he could remember, sought for another

entrance to the goldfields from the coast. He knew that the Indians were

following an easier route, and questioned them closely, but they were

astute. They were making money at the expense of the gold-seekers. They

were packing goods and supplies into the Klondyke on their backs for the

miners. With their loads they scurried out of Skaguay, and were not seen

again until they arrived at the Golden City. Where they traversed the

mountains no one knew, and the white men were not sufficiently daring to

attempt to track them, as the Indian reads the forest like a book, and

never gets lost, while the white man was liable to get stranded, and to

be played out before he had gone two score miles. Captain Moore knew the

Chilkoot Pass through and through, having traversed the country long

before gold was discovered, but he was bent on discovering the red men’s

secret, as he was convinced that it was better than the Chilkoot Pass.

The red men hesitated to betray their path, because they feared that the

white man would come along with his pack-trains, and put them out of

business.

Not to be discouraged,

Captain Moore started oxE, and trailed over the mountains, following in

the tracks of the Indians, which he picked up quite easily, and the

White Pass route was found. Then he sailed south to Victoria, and

unfolded his plans to a Development Company. This organization lost no

time in profiting by the discovery. Men were enrolled, and with

pack-horses bearing provisions and tools, they hacked a way from Skaguay

to Lake Bennett. The trail-cutters made money out of the transaction, as

wages ruled high, some of the boys netting a comfortable 16s. per day,

with everything found, during the short Northern summer. It was a trail

in the fullest sense of the word, being a mere clearing about 2 feet

wide, through the bush, with corduroys, or log bridges, over the

mud-holes, and stones thrown into the beds of creeks or rivulets through

which the pack-trains splashed their upward way.

Directly this trail was

opened a rush set in. The fact that the White Pass was easier than the

fearful Chilkoot, with its blood-freezing winds, was noised far and

wide. The volume of traffic was tremendous, and, as may be supposed,

owing to the trail having been cut very rapidly, it broke down. Horses

floundered in the morass, breaking limbs and irrevocably damaging packs

men slipped down steep slopes to pull up with broken necks at the bottom

of rifts; and the contents of packages were scattered in all directions

against tree stumps and boulders. The trail became a churned-up mass of

mud, stones, and falls of de ad wood, and man] pack-trains were held up

for hours while the process of fixing was carried out, to enable the

animals to go forward. Yet, despite these drawbacks, over 3,00(' miners

wrestled with the difficulties during the first season the trail was

open, in their mad haste to gain the coloured creeks and waters of the

Yukon. The Chilkoot Pass slipped from favour, and only the most daring

ventured to scale its summit. And to-day even the White Pass trail is

only a haunting memory. The iron horse has entered the country under

British enterprise. and carries the miners and their belongings to and

fro quickly and in comfort.

Although the building

of the railway wiped out the hazardous track over the mountains, it

comes to a dead stop at White Horse, and from this point there extends a

“road” to Dawson City, over -which the Royal Mail is carried during the

winter to the isolated city on Parallel 64°. It is a busy highway, too,

for the traffic has increased so much that the dog-sleds which formerly

sufficed to carry the letters to and fro, are now replaced by

horse-drawn vehicles.

Yet it is a wicked

road. It exists for the most part in imagination. For sixty-five miles

it extends over an upper layer of moss and decayed vegetation resting on

subterranean springs and lagoons. It is as soft as a halfcooled jelly,

and everything sinks as easily into it as if it were quicksand. It can

onlj be used by the mail for a few months in the year, when the boggy

mass is frozen as hard as a rook to a depth of several feet, and there

is a good layer of snow on top to form an excellent surface for the

sleighs. The grades are back-breaking, and the devastation wrought by

wash-outs has caused the road to be built several times over. It coat

the Canadian Government a solid £5,000 to run those sixty-five miles, if

just merely clearing away the brush over a certain width, easing banks,

and corduroying the worst patches may be termed building a road, and the

men engaged in the task had one ox the stiffest fights against Nature

that has ever been accomplished.

But probably the worst

trail ever carried out in the annals of Canadian history was that from

Edmonton overland to the Klondyke. It involved one of the hardest

journeys on record, tracing a way through unknown country for hundreds

of miles. Private initiative shrank from the perils; men willing to risk

their lives and limbs in cleaving a 2-foot way for the passage of

gold-fever stricken fools were not to bo found at any wage. So the task

fell upon the North-West Mounted Police. This famous corps has achieved

many brilliant exploits, but the cutting of the Klondyke trail stands

out pro-eminent. One of my companions on the trail had assisted in that

undertaking, and had vowed that never more would he be seen swinging an

axe to cut a way through the virgin forest for any pack-train on this

earth. It was a nightmare from start to finish, and the only wonder is

that the task was ever completed. When the police set out, it was hoped

that they would be assisted by the Indians, but the country traversed

proved to be as void of human life as the ice fields around the poles.

The monotony and silence nearly drove the trail-cutters mad. Only at

very rare intervals did they see a face outside the members of their own

party—when the pack-train came up with provisions. Accidents were

numerous, but they had to patch up the sufferers as best they could, aa

there was not a doctor within 2,000 miles. On one occasion, while one of

the party was swinging his axe to bring down a spruce, his numbed

fingers played him false. The razor-edge missed the track and pulled up

short and sharp against his foot, cutting through the leather boot as if

it were paper. His limb was cut wellnigh in half. His comrades picked

him up, and with the cleanest pieces of rag they could find dust-laden

lining tom from their clothes—they bound up the wound, and staunched the

flow of blood. The sufferer grew worse, the loss of blood precipitating

what promised to be a fatal illness. Ha was in need of delicate foods,

but they had nothing but the rough trail fare to offer him, comprised

for the most part of pork and beans. They dreaded blood poisoning, but

were spared this scourge fortunately, as they persistently washed the

wound with pure hot and cold water.

The patient’s steel

constitution, tempered by the blasts of winter, and the open air, and

hard life, pulled him round. In the course of a few weeks, he was about

and once be felt his feet he mended rapidly, so that it was not long

before be was once more wielding his axe with his companions.

It is not surprising,

under these circumstances, that men are difficult to obtain for cutting

trails. The wages are high---anything from 8s. to 20s. per day may be

earned, with food—but silent Nature very soon bludgeons the trail-cutter

back to civilization. Some men seem born to this work, but backing brash

from misty morn to dusky twilight in a very short time plays havoc with

a man.

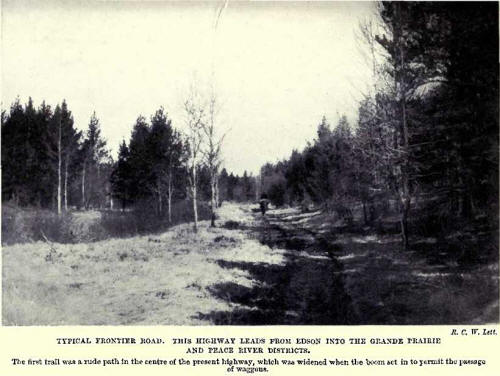

As the new country is

opened up, the traffic becomes too heavy for the pack-train. The 2-foot

pathway must be widened cut to admit of the passage of wheeled vehicles.

The road-builder then appears upon the scene. At the present moment the

driving cf frontier roadways is very active. Both the Dominion, the

Provincial, and the British Columbia Governments are laying out

considerable rum? in this direction. The general practice is to build

the road by direct labour, but now and again private enterprise is

entrusted with the task. The scale of payment varies according to the

country in which the work is being carried out, and the characteristics

of the employer.

The pioneer or frontier

road differs very considerably from that to which the city dweller is

accustomed. In comparison it is not a road at all, but merely a swathe

through the forest. The standard width is 60 feet, and the first

operation is the clearing of the brush and the levelling of the trees

within the confines of this band. The scrub is levelled to within a few

inches of the ground. The undergrowth and tree stumps cannot break out

into fresh growth as the parsing traffic kicks the life out of them.

When the swathe has been driven from point to point, the grading

commences. The tree stumps are pulled out in much the same perfunctory

manner as a dentist removes offending molars, banks have the humps

scraped off by machines hauled by horses so as to reduce the gradients

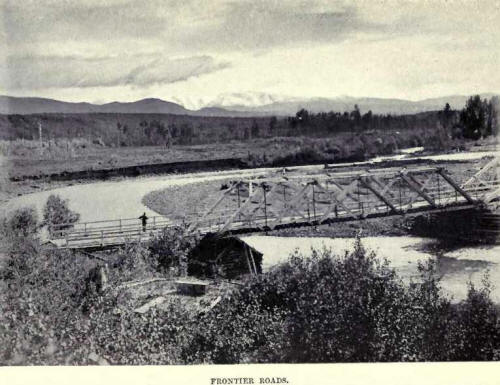

to facilitate the passage of waggons, while creeks and rivers arc

bridged or equipped with current ferries. The backwoods bridge is a

crude, cheap structure, though extremely serviceable. Long strong logs

are laid athwart the waterway, be that the ends rest on either bank.

Upon this foundation other logs, sawn to the right length, are laid

crosswise and close; together. Then two other long logs are laid on

either side parallel to the foundation, and immediately above, with the

ends of the cross piece between. The whole fabric is clinched together

by long, wooden, wedge-like pegs, placed at frequent intervals. The read

surface is formed by the rounded sides of the logs, which, under the

passing traffic, become smoothed off level as if given a Hat surface by

an adze or plane.

Every spring these

bridges have to be overhauled. The creeks, swollen by melting snows,

rise, and either lift the structure off its foundations or else break it

up more or less, while the logs themselves, forming the deck, suffer

from the ravages of wear and weather. Then the roadway has to he renewed

at the end of winter, ad it becomes obstructed by the tall 1hick trees,

which have been brought to earth by the wind. Every spring a gang has to

go out to fix the primitive highway. As for its surface, this is as

Nature left it—the day when the steam-roller and macadam will be

required is very remote. The passing wheels of vehicles ram down the

ground on either side, and in time carve out deep ruts, so that no

difficulty is ever experienced in keeping to the right-of-way, though

trouble may be experienced in trying to turn suddenly at right angles.

The muskeg is overcome by means of “corduroying’’—that is, fashioning a

structure similar to that of the log bridge, and laying it upon the

surface of the bog.

In Now Ontario where

the new transcontinental line crosses a 200-mile spur running up from

the south, gold was discovered at Porcupine. Instantly the inevitable

rush set in. When I was there shortly after the strike, the countryside

was littered with goods waiting to go in, but impossible to transport

because the trail was so difficult. The Ontario Government came to the

rescue, and pouring gangs of men up-country, the forest soon resounded

with the savage strokes of the axe, as brawn and muscle cleared the 60

foot wide swathe through the trees for the worst nine miles.

In the West the

authorities, realizing the significance of the boom of the Peace River

country, have widened out and improved the old execrable trail to a

highway, along which a motor-car can rumble so long as it carries rope

and tackle, to haul itself dear of mud-holes, and is fitted with

powerful springs capable of withstanding a mechanical hopping, skipping,

and jumping. In New British Columbia roads are being driven in all

directions, this Government having embarked upon a very frightened and

broadminded road-building policy. The most important highway is the

420-mile track running through the length of the country northwards of

the Cariboo Road. When we swung off the rock-strewn trail and hit this

primitive thoroughfare, we blessed the Government. The pace of the

pack-train quickened from two to nearly three and a half miles per hour.

Numerous laterals are being built on either bide, tapping promising

points, so that the settlers, when they surge in during the next two

years, will find excellent vehicular canals striking through the bush.

The men mot on these

frontier road-building operations are of a peculiar type. Many have

tried their hands at nearly every occupation, and have struck bad luck

at one and all. They could get a better job down in the cities, but they

resent the confinement. Some will tell you harrowing stories cf the

trail in the search for gold, and what an illusion the quest is when the

fields are reached. Others have been out prospecting without spiking a

sign of anything but black sand, which never gave a reflection of

colours; or have been trapping, but the animals could always scent their

traps a mile away, and accordingly gave them a wide berth. Some have put

their hands to farming, but their crops would not grow; or at

fruit-raising, but the trees appeared to be disgusted with the land in

which they were being reared-and died. Some of the younger fraternity

are out to get their first experience of the wilds.

The men roll out of

their tents about seven in the morning, swallow a good hearty breakfast,

and then are on the road hacking down trees, pulling out stumps, or

grading until about six in the evening, with an hour’s break for the

midday meal. Supper over, the time is frittered away according to

individual inclination, a good many sitting round the camp fire swapping

stories of ill luck, between puffs of tobacco, and enlightening the

younger members on the caprices of Fortune.

The pay averages about

11s. per day in the Government employ up-country. The men have to board

themselves, although the services of a cook are supplied at the

Government’s expense, inasmuch as no frontier working camp can be kept

going without an expert master of the canvas kitchen and the

wood-burning range. The men, as a rub, depute the cook to the additional

honorary office of housekeeper, one and all subscribing an equal amount

per day for their upkeep. The Government supply the goods required at

cost price, but when the men are working in a remote territory suffering

from lack of transportation facilities, the freightage charges are

liable to enhance the prices by 50 or more per cent. Still, striking the

average, about 2s. per day per head (to which fund the cook also

contributes) generally suffice to meat the requirements of the table,

giving a varied and plentiful menu. The men themselves in their spare

time arc able to contribute to the fare by means of fish, far, and

feather from the woods and streams, at the same time gaining excellent

sport. Taken on the whole, employment among the road builders in the

frontier districts can be relied upon to bring in a steady 8s. a day;

and as there is no social position to maintain, incidental expenditure

being confined to the purchase of little luxuries such as tobacco, a

single season’s employment should bring in about £80.

On the Government

contracts the cost of building the first road averages from £70 to £80

per mile, this expenditure being represented almost entirely by labour.

Now and again the cost will be inflated by the necessary erection of a

somewhat pretentious bridge—in timber— over a river, or the installation

of a ferry, but this is abnormal expenditure. In the first instance the

Government sometimes prefers to permit private enterprise to carry out

the bridge, subsequently settling the bill with those who participated

in the scheme, such as, perhaps, a band of farmers, or settlers, who

have co-operated together in the project to meet general convenience.

At times the

construction of a new road is carried out by contract, and then the

private individual striv3s to make the most out of the undertaking. Some

of these contractors attempt to cut the scale of wages hoping to enrol

Norwegians, Russians, and other foreigners who are not familiar with the

conditions of the country, or will even endeavour to press the Chinaman

into service. But at times these carefully-laid schemes are sent to the

four winds.

There was one

contractor in the West -who, having had his tender accepted, thought he

saw himself well established on the road towards being a millionaire. He

figured it up very carefully, and the paper results were highly

gratifying—to himself. He came to the conclusion that 6s. a day would be

ample for labour, notwithstanding the fact that the ruling scale in his

vicinity was 10s. per diem for the lowest grades of unskilled labour.

He started work, and

the labourers appeared on the scene thinking the general wage was

certain to be paid. When they learned the actual scale a riot almost

broke out. The contractor dared them to do their worst, and he collected

some hard-up emigrants searching for work in a neighbouring town. When

they appeared on the job, the dissatisfied workmen rounded up the new

arrivals, explained the situation, and wooed them away. The contractor

was furious. This was a contretemps ho had not anticipated. He scorned

farther afield, and brought in another large gang of foreigners, even

paying their railway fares. They were intercepted in the same way, and

throw down their tools. The original workmen hung about the contractor’s

place and jeered him “to get a move on” with his job. Thoroughly

infuriated, the latter resolved to employ Chinese labour, and that acted

as the red rag to the bull. Directly the yellow-men, who aro notorious

in undercutting white labour, arrived, there was one long howl. The

contractor laughed and jelled out that he had got the best of the

bargain. But the white men were not going to bo overridden so easily.

Each returned to his shack, routed out his shotgun. revolver, or what

other firearm he could command, and returned to the scene. Things looked

ominous, but there was no intention to promote bloodshed. Ono of the

workmen, a tall, athletic English fellow, was deputed to explain to the

Chinamen that they had belter clear out as soon as they could, or else

his pards would be compelled to indulge in the gentle sport of

“chink-chasing.” The Chinamen took the hint and threw down their tools.

At last the contractor

saw that he would have to cut his paper profits down so he gave in; he

would pay 10s. a day. But the English spokesman shook his head: “No. you

son of a gun! You’ve held us up trying to sweat prices. Now we’re going

to hold you up. Not a move is made on that jot until you agree to pay

sixteen shillings a day. You see, we’ve lost time in hanging out, and

we’ve got to make geed our losses.”

The contractor stormed,

threatened, and cursed. He pointed cut that he would lose over the job

on that scale of pay, but his remonstrances were of no avail. “Sixteen

shillings or nothing,” was the ultimatum. He held out for a few hours,

and then reluctantly agreed. Instantly the dirt began to fly. “We didn’t

see much of the boss on that job,” the young Englishman chuckled. “I

guess he put in most of his time figuring how he would come out of it

when we had finished ” |