|

When winter spreads her

while mantle over the country, bowing down the trees as if in sorrow at

the braking of the wheels of progress, and the ground is hidden from

sight ; when Jack Frost catches all the waterways in his relentless icy

grip, the wilderness is closed. Those within are incarcerated almost as

lightly as if behind prison bars, while those without are as much

baffled in trying to get in as if the confines bristled with guns

against an invading army. All the occupations of the summer are brought

to a close. The packer has hitched his horses on the home ranch ; the

prospector has struck his camp or locked the door of his shack ; the

surveyor has picked up his transit and level; the timber cruiser has

folded up his notebook and stowed it away in his pocket—all who find a

living in the wilds when the waterways are open, and the trails are

visible in the gloom of the trees, seek sanctuary in the nearest towns,

unravelling the results of the summer’s work, weighing up their chances

of success, all marking time more or less until the winter break3. when

they hark back once more to the fields of their labours.

Everything in a new

country is brought practically to a standstill. Even that native

inhabitant of the woods, the bear, tucks himself away in a snug retreat,

and waits until the clock of springtime recommences ticking. The only

break to the eternal peace and solitude —white as a harbinger of peace

is represented in its most compelling form—is afforded by a stray Indian

with his huskies, or perhaps a dog-train trailing or, as it is locally

called, mushing along with infinite effort through the blizzard, braving

the fates above, with His Majesty’s mails aboard for some remote

settlement, because somehow or other, in the wilderness, as in the

settled country, the mail service must be kept going. The logging camps

are busy, but the circle of their activity is so small as to be an

indecipherable dot upon the enormous landscape.

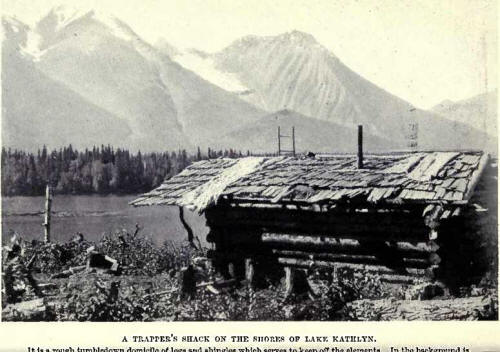

Yet one form of human

life ekes out an existence, and profitably at times. This is tho

trapper. As a rule ho is generally a packer, a prospector, or some other

human denizen of the wilds, who cannot tolerate kicking his heels about

a town for three or four months, and who would rather brave the silent

white tomb in the endeavour to make ends meet than occupy his mind in

the town until he can resume his natural occupation.

It demands no

supernatural powers to distinguish a trapper whenever and wherever you

see him. He betrays his calling whether he is sitting round a camp fire,

on the verandah of a hotel, or in a cosy drawing-room. He is eternally

whittling wood and sharpening his knife. These employments for idle

hands come as naturally to him as it is instinctive to move the teeth in

order to masticate food, or to blink the eyes. Even when he is

conversing ho is incessantly whittling meanwhile.

Why is it? This was the

question asked me by a young lady when her brother came home from Canada

one winter. He had little regard for the drawing-room pile carpet. To

sit down in a chair and pass his time in accordance with time-honoured

etiquette was absolutely impossible to him. He pulled out his knife, and

absent-mindedly ran it up and down the aim of the mahogany chair, to the

intense horror of his mother. When recalled to his senses, he wandered

into the depths of the house, and returned as delighted with a few

sticks of -wood as if he had struck a gold mine. The rest of the evening

he amused himself whittling away, strewing the carpet with chips,

conversing slightly meanwhile. Ever after that a few sticks of wood were

placed prominently on the hearth to amuse him and to save the furniture

from his vandalism. Yet, if that wondering young lady and horrified

mother had been with the young man in the wilds trying to keep body and

soul together during the long winter, 300 miles or more from the nearest

town, they would have understood.

Whittling is the only

thing that keeps the trapper alive when he is not busy with his

captures. And it must be confessed that more time is spent in whittling

wood than in any other occupation. If it were not for whittling, the

trapper •would go mad; it takes Old Father Time off his hands.

Trapping sounds

attractive, and it constitutes a fine romantic peg upon which to hang

adventurous fiction, but when you meet the trapper at his trade in the

silent wilds, there are precious few signs of romance apparent. A grind

on the treadmill is paradise in comparison. Milady bedecks herself in

rich furs and is the envy of her neighbours and friends in the

fashionable city, but does she ever give a thought to the moil, the

wasting of blood and tissue, the stunning of the brain, the blighting of

hopes for which those firs have been responsible ? If she did, they

would not rest so lightly on her shoulders. Isolated confinement in its

worst form, living in such a way that body and soul are just kept

together and no more, the deprivation cf the sight of a human face for

months, more likely than not, has been the price of that gay attire,

with perhaps a life or two that no one cares twopence about thrown in.

Few furs are worn that do not hold the story of a grim fight for life.

Somehow the frost-bound

wilderness calls the young and old. It entices them within its embrace,

often never to let them escape. If the man is on serious business bent,

he perhaps seeks) a chum, not for conversation, because in a week all

topics are worn threadbare, but just to get the sight of a human face.

They gain their centre of activity and camp is pitched. Round this, in a

circle of many miles diameter, a string of traps for the marten, bear,

and other quarries, are set. In the morning the two discuss their sparse

meal of pork and beans, washed down with tea if they have it, otherwise

with luke-warm water. Then the examination of the traps commences. The

circular trail is divided in two. One goes off on the eastern society,

the other takes the western section. Maybe it is a tramp of twenty miles

or so to the outermost point and back. They meet where the semicircles

come together, and one anxiously looks to see if the other has had any

luck. If favourable, they display their prizes for each other’s

approbation; if not, they tramp wearily back to camp as silent as

funeral mutes, and settle down to the evening meal.

The prizes to be won

are not so common as might be supposed. One young fellow related how he

and his chum trod the semicircles day after day for three weeks, and

never found even a rabbit in a. trap. Such ill-luck as this knocks the

heart out of all but the strongest men. He was used to it as he had put

in several winters at the game; but he had a raw lad with him this

winter, and the latter, when he saw how things were going, could not

resist giving way, and curbing the stars above for luring him on to such

a crazy fortune-hunting scheme. They spent four months in this camp, and

when they returned to civilization, they found that their imprisonment

and privations had brought them £20 apiece. The raw lad forswore

trapping ever after, but his older chum gave a short, rasping laugh.

“Why, it’s the luck of the life.” He took the fat with the lean years.

The former three winters in succession had been lucky to him, for he had

netted over £100 in four months on each occasion. He knew he could not

expect to maintain this average, but he confessed that it was rough for

the tenderfoot to have a misdeal on the first round.

Trapping is more a game

of luck than oven gold prospecting. .In the latter instance you have a

chance, perhaps a long one, but knowledge helps you. In trapping you are

at the free end of Fortune’s string. Possibly the Indians have been

ahead of you, and have skinned a promising country of every trace of fur

and feather because the red man is a relentless hunter. He shoots

everything on sight. If a complaint is levelled against his tactics, he

is always ready with the retort that “his existence depends upon

hunting, and he must live.” The Government, however, is realizing the

folly of this truism, and is closing large tracts of land against even

Indian despoliation.

The task of the trapper

has been rendered harder by the march of civilization. As the white

settlers spread out reclaiming the land for agricultural and development

purposes, the game retreats. To-day the trapper is driven almost to the

Arctic circle to prosecute his activities. Then, again, several of the

most valuable animals from the commercial point of view have come under

the protective wing of the Government. The beaver and the moose in

particular are cases in point. This has been done to save these animals

from extermination. For the most part the white man respects the law,

but the Indian does not. I was at one Hudson Bay trading post when a

stranger, who did not know the ropes, called and tried to trade a score

of beaver skins.

The factor looked at

him with ill-concealed contempt.

“What right had a white

man about here with beaver skins?”

The stranger was

nonplussed.

“Say, sonny, you had

better got shot of that load right away,” the factor went on, “or you’ll

get into the cage.”

The man departed

crestfallen. It must be admitted that the authorities press home their

powers with vigilance and severity. One well-known trading company got

enough with a large stock of several hundred beaver skims in a western

town. The whole lot was confiscated and destroyed, while the company was

mulcted ;n several thousand pounds for trading in illicit fur.

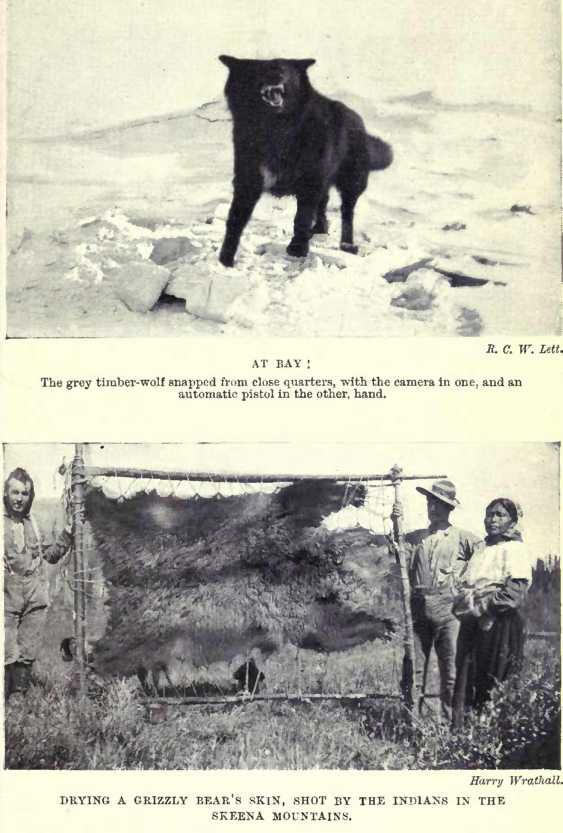

Practically every

animal receives a. certain need of protection during the year, with

perhaps the solitary exception of the wolf family. This animal is

exterminated with as little compunction as therat. The finest specimens

are massive brutes, and tough foes to overcome, while the fact that they

run in pucks during the winter renders them a severe menace to the

safety of small isolated communities. As a rule they are too cunning to

be trapped, and are generally shot down. The bear is a good prize, and

is in his prime in the first stretches of spring, when his pelt is in

magnificent condition. A hole is his favourite hiding place, and in

these pits traps, massive creations of wood, are formed by dint of much

effort on the part of the trapper.

The richest fur centre

in the Hudson Bay Company’s territory is Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie

River. It serves a district extending over 1,200 square miles in length

by as far north as the trapper cares to go, and derives its supply of

furs from thirteen other posts. In the heyday of its prosperity, the

shipment of furs from this post to the value of £20,000 in a season was

considered a poor total, but this aggregate under present prices would

represent over £50,000.

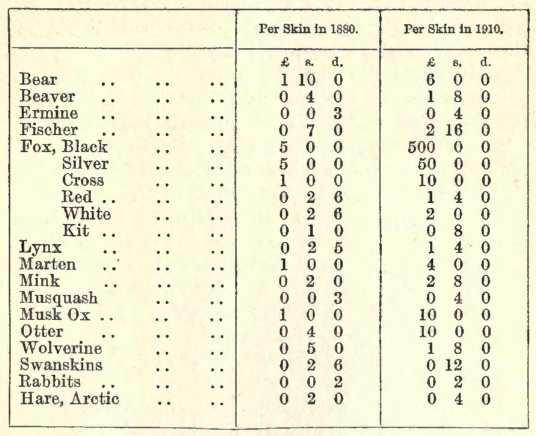

The gradual and

persistent narrowing down of the fur-bearing country, and the coincident

necessity of the trapper to penetrate into more and more inaccessible

regions, has resulted in a pronounced increase in the value of furs. One

of the Hudson Bay trading factors, who has spent some forty years in the

wild frost-bound north, gave me the following table of fur-values, which

shows readily how prices have risen during a period of thirty years:

The black fox is the

Royal fur, and has become exceedingly scarce; so much so, that the

trapper who secures one of these must be considered as having an

unprecedentedly good streak of luck. They come into the market very

seldom indeed. One was sold at Edmonton some two or three years ago, and

before the hammer fell, the bidding had risen to €500.

Many strange adventures

have been written around the trapper’s life, and the romance fires the

imaginative mind. But one experience is generally sufficient for the

tenderfoot, when the calling is found stripped of all its romantic

details. At the present moment it is the most precarious means of

earning a living in Canada, while the chances of coming in at the end of

the winter with insufficient prizes to defray the cost of the

expedition, are overwhelmingly greater than the possibilities of making

a good haul, unless one is prepared to penetrate into the most

inaccessible and more forbidding districts to the extreme north. Then

the difficulties attending transit and the packing of provisions must be

born in mind. There are still some rich fur-bearing districts to the

eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, north of the Fraser River, and

fur bear along the northern coasts favouring the Skeena, Stickine, and

Naas Rivers. Some of the higher slopes of the lower hills of the

interior of British Columbia, such as around Tachick Lake, are thickly

infested with game, but for the most part this more easily accessible

country has been skinned by the Indians.

Numerous thrilling

adventures may be recounted of the life and they are mostly of a

desperate character. One old trapper who had established himself

permanently in a good country, had run up a comfortable shack, and dwelt

there with his wife and child; he was out on an expedition with the

latter one day, when, on the homeward journey, and within hailing

distance of his home, he tumbled across a bear with her two cubs. It was

the early spring, the snow still lay in patches under the trees, and the

boar, having her young with her, was both hungry and savage. The trapper

scuttled his son into the bush and then drew on the bear. Ho missed the

mother, but bowled over one of the cubs, wounding it mortally. The bear

tended her shrieking offspring and glancing round caught sight of the

trapper barely twenty paces distant. She made for him. The man stood his

ground, and taking careful aim, let drive. The bullet missed and

evidently the sight on his weapon had become deranged from some cause or

other, because four other shots, while hitting the enraged lady, did not

stop her, but merely increased her fury. They came to close grips, the

trapper discarding his useless firearm and drawing his murderous knife

from its sheath.

A desperate battle for

life ensued, with the odds all on the side of the bear. She endeavoured

to get the man within her deadly embrace, but he kept plunging his knife

up to the hilt in her body, dodging, twisting, and slashing her forepaws

wickedly. Blood coursed from the animal’s body in a dozen streams,

smothering her opponent until he presented a ghastly sight. The

trapper's son, anxious to extend what help he could, ventured from his

concealment and stared in wonder.

The father caught sight

of his terrified boy, and cried excitedly, “Run home, sonny! Tell your

mother I shall not be long!” and the youngster sped homewards as fast as

his little legs could carry him, to relate how father was fighting with

a bear.

The tussle did not last

much longer. The bear overpowered the hunter, hugged, and clawed the

life out of him. When the agonized mother, who, upon hearing her child’s

story, had snatched a gun and rushed off to help her consort, reached

the scene, she found both burner and hunted lifeless. The man was still

in the brute’s deadly embrace, and was scarcely recognizable. The bear

had torn his clothes to ribbons, and his face was scratched to shreds.

His ribs and breastbone were smashed—crushed by the fearful hug of the

boar. Both were reeking with blood. The bear’s skin was absolutely

riddled with knife cuts, showing the terrible character of the man’s

fight for life, and his band was clenched to the knife, which was buried

up to the hilt in the bear’s heart.

Another trapper had

quite as exciting and uncanny an adventure. He was one of a small party

of trappers who had pushed into the far northern country so as to have a

better opportunity to get a good haul. One and all were skilled men,

having followed this pursuit for years. They had pitched an excellent

comp, and their general procedure was to sally out every morning,

returning at nightfall with the pelts of whatever prizes they had snared

in their traps, or brought down with the rifles.

The country was badly

broken, and the snow was thick and heavy. One day, one of the men, about

four miles from the camp, was floundering among the hummocks of snow,

when suddenly he gave a yell as his feet slipped from under him He shot

from brilliant daylight into inky blackness in an instant, and pulled up

with a nasty jar. He had fallen into a hole which he had not seen,

because a fallen tree had covered its mouth; directly he had trodden

upon the covered branches the rotting fabric had given way beneath his

weight.

He lay half-stunned for

some few minutes, and then carefully moving his limbs, was gratified to

find that no bones were broken, though he was sorely bruised. While he

was wondering what he should do. he heard a sound that jerked him bolt

upright as if he had been electrocuted. It was an ominous growl from the

opposite side of the hole. The truth flashed on him in an instant; he

had tumbled into a bear’s lair! He received ample evidence of this

unwelcome fact, for while he was listening intently and endeavouring to

peer through the gloom, he felt a lick at his hands, and a scratching at

his legs. Phew! she had got cubs! This was a desperate position. He

stretched his hand above his head to feel if he could got a foothold in

the rock and thus climb nut, but the wall was as smooth as a board after

a jack-plane had been run over it.

Big beads of

perspiration broke out on his forehead. His gun was twenty feet above,

on the snow outside, as he had involuntarily dropped it when he felt his

feet slipping suddenly from beneath him. He had his knife, but he knew

he would stand very little chance with it against his adversary ii he

provoked her to anger.

The cubs, however, did

not appear to resent his sudden intrusion, and considered him an

excellent plaything. Judging from their size he surmised that they were

about throe months old because the breaking of winter was almost due, at

which time the bears come out of their dens. He concluded that the best

thing would be to take his chance by keeping as quiet as possible,

inasmuch as when he was missed his “pards” would be certain to come out

to search for him. So he drew closer against the wall sat up, and

attempted to amuse the cubs. They were spitefully playful, and were

manifestly very anxious to try their claws upon him. Now and again he

would give one a cuff it did not appreciate, causing it to give vent to

a loud squeal, which was instantly answered by a growl of inquiry from

the other side of the den. The old lady had not observed his entrance,

or if she had scented him as she must have dene, she did not seem

inclined to tackle him. Now and again she would lumber over to where he

sat, knife in hand, ready for an attack, but she always went awav when

she saw her cubs were not being harmed. The latter at periodical

intervals returned to the mother, and thus gave the unfortunate trapper

a slight, well-earned respite from their antics.

When night fell, and he

could not see an inch in front of him, he wondered what was going to

happen. Sleep was impossible; fear kept him awake. Every other minute he

would start up thinking that ho felt the old brute sniffing him over.

Once she did make a close-examination, and when she reared up on her

hind-legs to the fullest extent of her 7-feet stature, he gripped his

knife more tightly than ever, and was ready to slip to one side out of

her deadly embrace.

When the morning broke,

and ho found himself still unscathed save for some scratches from the

cubs, he pulled himself to his feet quietly, and silently glided round

the den, feeling for some means of escape. With one eye on the corner

where the old lady was lurking, and his arm outstretched, feeling the

smooth rocky surface, he did not see where he was stumbling, and his

heart stood still when he trod on one of the cubs and provoked such a

squealing and growling that he thought his time had come. The old lady

evidently now concluded that something serious was the matter and

started off upon a close investigation. This was just what the trapper

did not want, as ho felt mischief was brewing. The mother ambled across

the den, and brushed against him; then she turned round with a fearful

growl. Here was the cause of her youngster’s disquietude. The trapper

saw that a fight was imminent, and, braced up with terror, he decided to

make a bold show. His knife was sharp, long, and his arm was supple and

steady. As the brute wheeled round, he gave a fearful lunge, ripping up

her side. Thoroughly roused, she sprang to the attack. Twice he got the

knife home, but as it was not in a vulnerable spot the blows were worse

than useless. Every time the bear advanced ho dodged her but more than

once it was only at the expense of a terrific drag of her claws, which

stripped his coat to ribbons and tore the flesh in parallel lines.

The fight wont on for

about half an hour—it seemed years to the trapper—and the two dodged

round and round the cave. The din was fearful, the cubs were squealing

at the tops of their voices, and the mother was growling savagely. Her

forepaws were reeking with blood, where the trapper had slashed them

with his knife, and the man was exhausted by his exertions and unequal

fight. Fortunately, the bear was in a similar plight, but she possessed

far more stamina and could keep up the contest for hours yet, whereas

the man felt as if he would fall every minute. While they were sparring

round and round the pit, he suddenly heard his name called. Giving a

glance upwards to the hole through which he had fallen, he saw the faces

of three of his chums who were searching for him. They had followed his

trails, had found his gun. and had observed also the hole in the fanow

from which most unearthly sounds were coming. From the volume of noise

they thought that half a dozen bears were fighting and quarrelling,

until it dawned upon them that their chum was in the pit.

The unfortunate trapper

gave a faint hail in reply, which warned his partners that they were

only in the nick of time. With feverish haste they started slashing away

at the hole with their axes, sending a shower of snow and other debris

into the pit. This development startled the bear and distracted her. The

trappers tore away at the hole as if for dear life, until they had got

an opening some 6 feet square. Then two, gripping their rifles, and able

to see into the pit, yelled to their unfortunate chum to stand clear.

The two rifles barked twice in unison and four shots settled Bruin. The

trapper in the lair was overcome by the reaction and fainted. Instantly

one dropped into the pit, which was about 12 feet deep, despatched both

the cubs, and then got to tending his prostrate chum. With great

difficulty ho was got out of the hole, revived, bound up, and carried

back to camp. The fever laid hold of him, and for over a week he raved

in delirium about hits desperate fight in the den. His wounds were

serious and refused to heal, while as the camp had no medical outfit of

any kind the sufferer’s distress could not be alleviated. As the winter

was breaking, they struck their camp, piled up their sledges, and

returned with extreme difficulty to the nearest settlement. Here they

were able to give their comrade better attention, but unfortunately

erysipelas supervened, and the poor fellow succumbed.

Some of the old

trappers still talk about this story. They do not speculate as to what

they would have done had they been pitched into the same quandary; that

is not the trapper’s wav. They merely relate the story, shrug their

shoulders, and finally dismiss it as “the luck of the life.” |