|

In Canada, as in other

countries, the telegraph is the herald of the settling forces of

civilization. Although the greater part of the telegraphic network

embraces settled country, linking cities, towns, and villager together

iii a continuous chain from coast to coast, yet there are several

hundred miles of line which even yet droop in festoons through virgin

forests forming a hairlike, albeit potential means of communication

between the remote isolated districts and civilization. These are

pioneer telegraphs in the fullest interpretation of the word. They are

laid out by the Government, upon inexpensive lines, being regarded as of

a temporary character, to await the coming of private enterprise as the

country is opened up to establish a permanent, up to date installation.

The Government merely breaks the ground with the initial frail link, and

generally in the end the system is handed over to a railway.

It is along the route

of the pioneer line where the most attractive atmosphere of adventure

and romance is encountered. There is nothing humdrum about the

telegraphist’s life in the lonely cabin on the mountain side, in the

swamp, or forest. “Tapping the key” upon a frontier electric wire had

none of that monotony associated with the selfsame calling in the

crowded cities. It offers an excellent opportunity to make good, not

only in regard to the pocket but to health au well.

It must be confessed

that in some situations the life is terribly lonely, but the wire-tapper

is far better off than his colleagues engaged in other up-country

occupations. He is in touch with the world at large. The ghost of the

wire ticks out in dot and dash precisely what is happening between the

two poles, and very often the operator in his cabin, five or six hundred

miles from the nearest town, will be found to be better posted up with

the affairs of the world, than the city dweller. The key and the sounder

are placed conveniently beside his bunk, and more than one operator has

confessed to me that during the darkest hours of the night, when the

forest is hushed save for the sounds of the prowling animals, and he has

endeavoured to woo sleep in vain, he has merely cut into the wire to

listen to what the world beyond is doing. If the business over the line

is slack, then the operator calls up a “chum” in a distant cabin,

perhaps 100 or 200 miles off, and holds a conversation, with as much

ease as if the two wore chatting round a camp fire.

One of the most

important and busiest of these frontier telegraphs is the “Yukon Wire,”

whereby the Klondyke is hitched up to London. One end of this line taps

the All-red cable route at the station of Ashcroft on the Canadian

Pacific Railway, 204 miles east of Vancouver, so that it cuts into the

main current of conversation between Britain and the Antipodes. From

this point it stretches in an unbroken line northwards through the

length of New British Columbia, piercing dense forests, touching

isolated Hudson Bay trading posts, spanning the wide shadowy valleys of

the north, and topping the snow-crested mountains hemming in Dawson City

and its hoard of yellow metal.

That line has a

history. The wire now trailing across the skyline was born of the

Klondike gold rush, but that wire, for the greater part of its distance,

was laid over the corpse of another brilliant undertaking. In the

sixties of the last century a group of financiers conceived the idea of

linking Now York with Paris and London, not by means of a cable resting

upon the bed of the Atlantic, but by means of an overhead wire running

through Asia. The United States system was to be tapped and led

northwards through British Columbia and Alaska to the shores of the

Behring Straits. A short length of submarine cable was to connect the

shores of the American and Asian continents, and then the wire was to

push its way through Siberia and European Russia to London. It was a

magnificent idea, which ended in a magnificent failure. Le Barge was at

the head of the scheme, and with his little band he set out axing a path

through the wilds with heavy pack-trains laden with wire. The going was

heavy, but by dint of dogged perseverance, the overcoming of prodigious

difficulties, and the experiencing of terrible privations, they hoisted

the wire as far as Telegraph Creek, south of the Klondyke, and clicked

with New York While the men were busily engaged in their round of toil

one day, the temporary sounder at the end of the line ticked out the

message that the Atlantic cable was laid and was working successfully.

The cable sounded the death-knell of the overland wire from New York to

Paris and London. The work was stopped there and then; the men throw

down their tool, the machinery was pitched into the ditch, and the party

made a mournful retreat southwards.

The line was forgotten

almost. It looped mournfully and silently through the trees so long as

the pots upon which it was supported braved the storm, and then came

crashing to the ground. The roaming Indians, when they desired a short

length of wire, clipped it from the overland telegraph, while the

remaining lengths writhed and twisted upon the ground under the

accumulation of falling and decaying vegetation. When 1 made my way

along this telegraph trail more than once my horse tripped over a

protruding loop of wire, and on several occasions while exploring I was

thrown unceremoniously to Mother Earth through my foot fouling the same

obstacle.

When the Yukon

telegraph line was built the same trail was followed. The broad straight

path winding over hill and dale which Le Barge’s forces had cut through

the bush half a century before was followed. It had become somewhat

overgrown with scrub, but this was quickly and easily cleared out, and

down the centre of the cleavage the poles were run, and the wire looped

and strained into position.

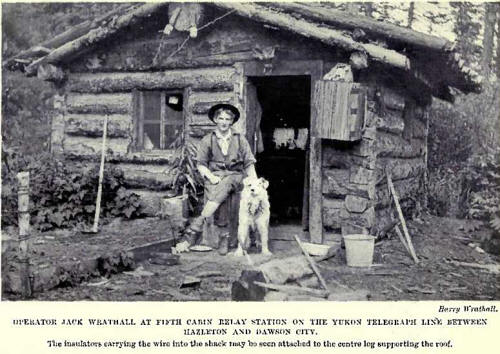

At intervals of about

thirty or fifty miles the operators and their cabin are stationed, the

distances between varying according to the country traversed. The cabin

comprises a wooden shack of the type common to the backwoods, containing

two or three compartments for the purposes of living and sleeping. The

instrument itself is set up on a small bench or even a table in a

convenient corner, lighted possibly by a candle thrust in the neck of a

bottle. Were it not for the two wires trailing from the post outside the

shack into the building, one might be pardoned for conceiving that the

home belonged to a homesteader, especially as it is generally surrounded

by a small well-stocked garden. There is very little evidence within of

the actual purport of the cabin. Possibly it is empty, but if not a

cheery Halloo is sure to be received, as the sight of a stranger is

welcomed by the lonely inmates.

Beside the shack is

another substantial log building. This is the cache, containing 6.000

pounds of supplies— sufficient for twelve months—and as already

mentioned, this larder is restocked once a year by the pack-train. The

Government is exceedingly attentive and liberal in ministering to the

wants of its isolated telegraphic employes, inasmuch as the comestibles

are of infinite variety, so far as is possible with preserved and dried

edibles, and there is very little likelihood of the party ever being

overwhelmed by famine. In regard to the fresh delicacies for the table,

their rest with the operators. Vegetables may be cultivated in the patch

around the shack, while the forest and streams yield abundant supplies

of game. In the more remote districts the table menu may be varied in

season with juicy bear-steaks, venison, grouse, mountain goat and sheep.

salmon and trout, which fall to the telegraph-operator’s rifle, or line.

Each cabin has two men.

Ore is the operator proper, and he is responsible for the transmission

of the messages. He has to be constantly on the alert, as often his

particular cabin has to serve as a relay station. That is to say, the

electric messages received from four or five cabins behind have to be

forwarded onwards, as it is not possible to despatch from Dawson City

direct to Ashcroft with the instruments employed. At first sight it may

seem a somewhat easy life, as there does not appear to be much cause for

heavy business with the Klondyke now that it has quietened down, but

this is far from being the case. At times the traffic is exceptionally

heavy, and the operator may be on relay duty for four or five hours at a

stretch going as hard as he can.

South of the Skeena

River the work is somewhat more arduous, as a branch line from Prince

Rupert, the new terminal port of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway cuts in

at Hazleton, and recently another wire has been carried to Stewart,

tapping the goldfields at that point. This renders Hazleton an important

clearing centre, as railway building operations have kept the line

busily engaged, for the simple reason that Prince Rupert has no other

telegraphic communication with the rest of the country.

The second operator is

the linesman, and his duty is to “ look for trouble,” otherwise to keep

the thin steel thread intact. He generally finds it, and it keeps him

going from morning to night, often the latter as well, as breakdowns

must be repaired instantly, so that the stream of dots and dashes

flashing to and fro may not be interrupted. The task is by no means

pimple, especially when the elements are antagonistic. The line is very

flimsily built, and it does not require a very great jolt upon the part

of the wind to bring the pole crashing to the ground. The forest fires,

however, are the greatest scourge, for they sweep through the parched

country, scorching up the posts by the score, or precipitating “dead

earths,” by which the current runs into the ground, in all directions.

Situate about midway

between each station is a small log shack, which is known as the

“halfway cabin.” This is the limit of the linesman’s patrol north and

south of the station to which he is attached, and as these halfway

houses may bo from fifteen to twenty-five miles apart on either side of

his station he may be responsible for the upkeep of thirty to fifty

miles of wire.

When the line has

broken down, and the fault has been located between two adjacent cabins,

the respective linesmen from each sally out looking for the cause of the

interruption. A few articles of food are slung across a horse’s back,

together with a blanket, and the linesman’s repair outfit, which

comprises the indispensable axe, a shovel, and one or two small tools.

He covers the trail beside the wire on his section where the fault

exists. Maybe he reaches the halfway cabin without discovering any

interruption on his part of the line. With his testing instrument he

taps the wire to call up his colleague. If it is all right and the day

is not too far advanced, he will return homewards straight away. If late

he will shake himself down for the right in the halfway house. The shack

is equipped with a stove, and it is not long before the evening meal is

ready, upon the conclusion of which he shakes up his rude bed in the

bunk and turns in. Maybe his chum from the next cabin who has patrolled

his section of the line for the fault reaches the halfway house the same

evening, and then the time is passed by the exchange of news-items,

anecdotes, and yarn*. The morning sees each remounting his horse, and

departing in an opposite direction back to his respective cabin.

Such a recital of the

day’s routine does not appear to offer much attraction or excitement,

but as a matter of fact, on the exposed stretches of the line the

linesman is out day after day, and sometimes does not pull into his

cabin for a week. Or perhaps, after riding hard for the whole day over

the length of line to the south to locate and repair a break, he reaches

home jaded and worn out, only to find that another interruption has

occurred on the north side, and without delay ho is off again. One of

the boys related to me that on one occasion he did not have a complete

night’s rest for about a month. The forest fires were fierce, and they

brought down the posts one after the other. Seeing that the posts are

slender trees about 4 inches in girth at the butt and about 15 feet in

length, rudely trimmed, they do not offer a very strong resistance to

the flames. As a matter of fact, the wire is far stronger than the

posts, and undoubtedly the wire does as much to hold up the posts as the

latter nerve to support the wire. If a post has collapsed under the

strain, out comes the axe, a young pine is soon levellod to the ground,

and a few minutes later it is stripped of its branches and crown. A

wooden bracket, carrying the glass insulator, is nailed to the top in

the twinkling of an eye, the wire is released from the prostrate post,

attached to the new one, a hole is dug, the pole is warped round until

its base is over the hole, there is a jerk and a hoist, and the next

moment it is standing more or less upright and rammed home.

Some of the experiences

of the linesmen in their search for trouble provide amusing reading. The

telegraph runs through the heart of the Indian country, and one might be

prompted to think that when the Red Men desired a piece of wire to

secure their fences or for some other purpose they might raid the

telegraph system. But it is not so. The Siwash has a profound regard for

that speaking wire; its potentialities have been brought home to him

time after time. Instead of regarding it in the light of a free

ironmongery store, he spares no effort to apprise the linesmen of any

defect that may become manifest, and will himself often re-erect a pole

that has tumbled down without breaking the wire, in order to save the

linesman a journey, and to earn his gratitude. But at times this desire

to be obliging oversteps the bounds of discretion.

The operator at one

cabin one night was relaying away merrily when suddenly to his amazement

he found that he was displaying his energy to no purpose; he was up

against a dead earth. The weather was calm, and outside there was not

the slightest glimmer of a forest fire reflected in the sky. What was

the matter? He roused his companion, the linesman, and the latter, dug

out of his bed, stole off amid many mutterings with the first streaks ox

dawn to ascertain the cause of the breakdown. He jogged along for mile

after mile, but there was no sign of a leak or break anywhere on his

section; the wire was as tight as a drum. In the course of a few hours

he drew up at the door of the halfway cabin, twenty miles distant, and

cut into the wire. He called his mate desperately, but without avail.

Then he tried the next cabin, and got the “O.K.” There was no doubt

about it; the break was somewhere on his own section, and he must have

missed the fault on his outward jaunt.

He turned his horse’s

head homewards, and sauntered slowly along, his eye glued to the wire.

When he reached home without striking success in his trouble, the

operator met him with the remark: “Why, can’t you find it?” The linesman

growled menacingly, and consigned the whole telegraph system to

perdition, for he was dead-beat, and, disgusted, turned into his bunk.

Early the next morning

he was out again, and made another run along the trail to see what was

the matter. He arrived at the halfway cabin as before with no luck. Once

again he went to call up his mate, and found that he was running to

earth. Scratching his head puzzlingly while he stood in the middle of

the shack, his eyes wandered round the gloomy abyss within the four

wooden walls, and then ho gave voice to a healthy curse. There, hung

from the stove, was a piece of wire which had been strung up by an

ingenious Siwash Indian to form a clothes line, and one end of this wire

was tangled round the telegraph wire, giving a “dead earth.” The dots

and dashes which were being poured so valiantly into that wire for

London were running into the ground via the stove! With an oath he

pulled down the offending makeshift, and gave another call through. His

mate answered instantly. Then, as he explained, he gave full vent to his

feelings for a whole five minutes, mounted his horse, and rode off

homewards at a gallop with his gun in his hands. It was fortunate for

the Siwash that the maddened linesman did not meet him, or there would

have been trouble of another description, for the man on the wire rained

curses innumerable upon the Red Man’s head, and would assuredly have

emphasized thorn with a hail of shot had the offender come within sight.

That improvised clothes line had held up the wire for two days, had

demanded a ride of eighty miles, and had ruined two nights’ peaceful

slumber.

Such incidents are a

mere interlude to the daily round, however. As a rule the search for

trouble is far more grim. Between Hazleton and Prince Rupert the slender

link threads heavy country, which is exposed to frequent rainstorms of

torrential fury, which play havoc with what is the hardest worked

section of the line. This stretch is nearly 300 miles in length. I rode

into one of the cabins between Hazleton and Fraser Lake one day, and the

operator, heavy-eyed and sleepy, was pounding away at his key for his

very life. He had been relaying for some few hours without a break. The

night before every man, both operator and linesman, on the stretch

between Hazleton and Prince Rupert, had been out in the pelting rain,

swathed in heavy slickers and top boots, trying to fix up the line which

had come down at a score or more places. When communication was restored

it was found that the Prince Rupert office was simply jammed up with a

heap of messages, and as the men who had been out were in urgent need of

rest, my friend was called upon to take over the duty of relaying for a

few hours.

When the line was first

opened only one man was stationed at each cabin, and he had to act both

as telegraphist and linesman. The result was somewhat disconcerting at

times, as occasionally the operator at a. station fell ill, and then

there was trouble of another description. One evening an operator

between Hazleton and Telegraph Creek endeavoured to call up his chum at

the next cabin north. To his dismay he could get no answer, though the

line was open. lie called and called, wondering what was the matter.

Presently there came a slow, long-drawn-out reply. The operator was

relating that he had been taken ill, and could hardly move the key. The

jerks and slowness with which the dots and dashes were rapped out

testified to the fact only too plainly that it was serious.

The first operator

switched his line through to the next cabin south, intimating the

trouble beyond, and that he was off to lend assistance. He had wellnigh

twenty miles to go through broken, densely forested country, and to make

matters worse the rain was tumbling down in bucketsful. Slipping on his

heavy waterproof, jamming a hunk of bannock and bacon in his pocket, and

with his gun in his hand, he set off. It was as black as pitch, and he

scarcely could keep to the trail, while time after time he made a

graceful toboggan along the ground when he stumbled over s deadfall.

Such unexpected incidents provoked bruises innumerable, and at last,

owing to the darkness, he struck a blind lead. It was some time before

he was able to realize that he had missed the trail owing to the

blackness of the night, but instinctively ho knew he had borne too much

to the west, and endeavoured to make up time by crashing through the

undergrowth to regain the correct path. As a result ho got more tangled

up than ever. He had been wandering around for nearly eight hours

according to his watch, which was nearly four o’clock in the morning. He

was quite lost, but piercing the gloom and spring an eminence rearing

above the trees he climbed to its summit in the hope that he might be

able to pick up his bearings. He was somewhat familiar with the country,

and only required some landmark to regain the trail. To his chagrin when

he gained the crest of the knoll he found that his perspective was

blotted out by the driving rain. Shivering with the cold, he waited some

time, vainly endeavouring to determine his position, but with no luck.

He was just on the point of giving up his efforts to pierce the gloom,

and about to trust to fate, when a faint light flickered through the

mist about two miles behind him.

It was the cabin, and

through missing the trail be had blundered beyond it. He strode off

towards this beacon and in less than an hour clicked up the latch. He

found the telegraph operator lying in his bunk almost delirious, in a

raging fever. Without any delay he called up the station south,

explained the situation, and asked for immediate assistance; then he

turned his attention to his companion. It was the hardest night’s work

he had ever put in according to his own statement, although ho had roved

the whole country through between Ashcroft and Dawson City. He had no

palliatives to his hand wherewith to relieve his wring c-hum, but ho did

the best he could until late the next day, when a relief hand and a

doctor pulled in. The operator had been knocked over by pneumonia, but

not realizing the gravity of his illness had held on uncomplainingly

until he collapsed. Under skilled attention he rallied quickly, and a

few days later went out for a rest and to recuperate.

The incident which

brought about the appointment of two men to each station was one of the

most convincing that could ha’s e been advanced for achieving an end for

which the men had agitated for some time previously. One of the

officials was making a journey of inspection over the line, and while

riding along one day his horse tripped over the languishing wire of the

old Overland telegraph, throwing him so heavily to the ground as to

break one of his legs. His companion restored the official as best he

could to Ms saddle, and although suffering excruciating agony, the two

made their way with painful slowness to the nearest cabin, intending to

call up assistance. They gained the shack, and to their dismay found

that the wire was broken down on either side, and that the solitary

operator was out looking for the trouble.

The cabin was as

isolated as if in the middle of the Sahara. It was useless to wait the

operator’s return or the restoration of the communication, so getting

astride his horse once more, despite the terrible pain it caused, the

two pushed on to the next cabin twenty miles away. What the official

suffered on that journey only he himself knew, but the climax wan

reached when the next cabin was gained after a journey of several hours,

because here communication was broken on either side through forest

fires, and the cabin was just as cut off as the next one north.

Fortunately the operator had not started off to repair the trouble, so

he was despatched for help as fast ab his horse would carry him. While

languishing in awful pain, accelerated by the long and aggravating jaunt

in the saddle over an exasperating trail, the official vowed that two

men should be appointed to every station, so that one man might always

be available for any emergency such aw this. It dawned upon him that a

lonely operator would be in a sad predicament if he met with such an

accident under such conditions during his duties. Forthwith each cabin

was given an operator and a linesman.

The wages paid to the

operators upon a frontier line vary according to the situation. On the

Yukon telegraph those engaged on the stretch between the Hkeena River

and Ashcroft receive a dear €15 per month, with everything found. This

country is more accessible than that between the Skeena River and

Klondyke, and the life is not so lonely. To make up for these adverse

influences, therefore, the operators on the latter section receive a

higher salary, averaging about £13 per month, with everything found.

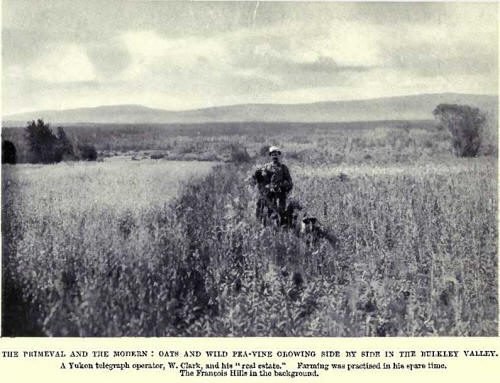

The majority of these

operators who have been able to tolerate the lonely life have made good

in other directions. The telegraph brought them into the country years

before the ordinary settler, speculator, and others who dabble in the

acquisition and disposal of land had learned of its arable fame. In

their leisure they scoured round, and staked fine stretches of Canadian

freehold at the prevailing figure, and by development have been able to

enhance its value very appreciably. More than one operator whom I met

had invested the whole of his salary in stretches of farming land,

buying it at the lowest figure, and to-day is in a position to command

whatever price he cares to demand. The operators have been compelled to

combine agriculture with telegraphy in order to occupy their spare

moments, which are many and frequent, and more than one has found the

job to be a means to an end; he has brought his holding of land to a

fine state of perfection while dwelling in the cabin housing the ticker,

so that in a few years he has been able to forsake the “key” for the

plough. |