|

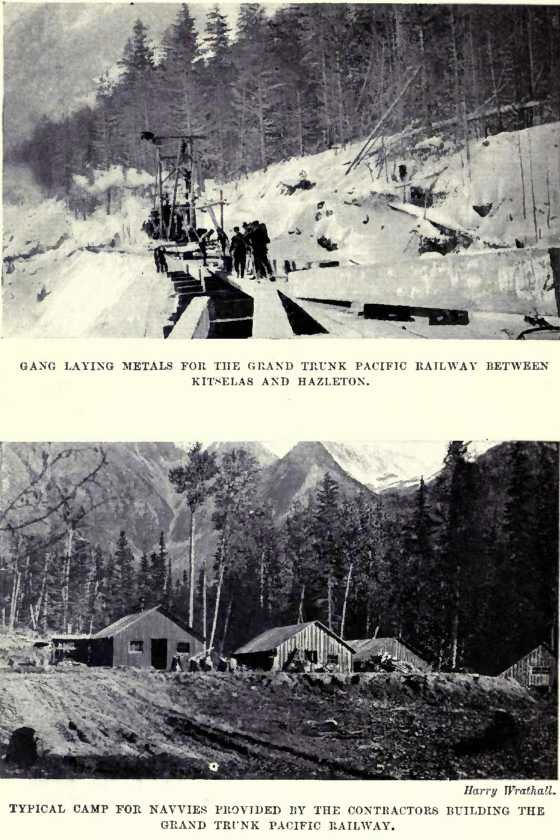

The West to-day offers

great attractions for unskilled labour, or rather for that class of

labour which experiences great difficulty to secure steady and

continuous employment under normal circumstances in crowded centres.

This demand is emphasized most potently in connection with railway

constructional operations, the foundation of new towns, the building of

streets, and so on, where the requisitions for skill are confined to the

manipulation of the pick, shovel, and wheelbarrow. Railway building is

exceptionally active, and will continue to be the first magnet to

attract labour for many years to come, as the steel highway is essential

in development work. Arrangements have been completed for building

several hundred miles of lines to criss-cross the country in all

directions, the greatest undertaking of this character being the

completion of the second and third transcontinental railways. One, the

Grand Trunk Pacific, is rapidly approaching completion, there being only

a gap of about 300 miles in the heart of New British Columbia to be

closed to provide a continuous steel highway 3,556 miles in length from

the Atlantic to the Pacific seaboard. The third transcontinental, the

Canadian Northern, at the moment is engaged busily upon its mountain

section of 600 odd miles from Port Mann, near Vancouver, to the

Yellowhead Pass. These two enterprises alone will command the services

of 10,000 men, fit and able to use the above-mentioned tools. In

addition, the Canadian Pacific Railway is pursuing an active branch-line

policy to tap new and promising districts, as well as the improvement of

its existing system to meet the spirited competition which is

developing.

In the Great West

navvying may be considered as being the most steady form of employment,

because the work is pursued uninterruptedly upon such tasks as railway

construction, the whole, year through, irrespective of the elements and

seasons. The grader, as he is called, is a hard worker, but the pay

taker, on the whole is adequate for the hire. East of the Rockies it

averages about 8s. per day; between the Rockies and the Pacific

seaboard, where labour is somewhat scarcer, the remuneration is

proportionately higher, as much as 12s. a day being offered per man in

return for the sweat of his brow. The reason is that keen competition

for brawn and muscle prevails in the latter new country. During the

summer in Northern British Columbia the navvy has no difficulty to earn

as much as twenty shillings per day when accompanying prospecting and

developing expeditions.

The navvy’s life in the

West is vastly different from tha t which obtains in the Old World. Here

a man can look forward only to a weekly income between 21s. and 25s. per

week, and it is a precarious livelihood at that. Then a third of this

wage approximately has to be expended on rent, so that precious little

is left to keep body and soul together. Contrast this condition of

affairs with a similar situation in Western Canada. The wages average

from 40s. to 45s. for a six-day week, and fully one half of this amount

is available to the worker to spend as he pleases. There is no deduction

for rent, as the grader shakes down in the camp’s bunk-house. Living

expenses absorb about 21s. per week, being an average of Is. per meal,

or 3s. per day. The only remaining essential expenditure is the

deduction of Is. per week, which is levied as a contribution towards

medical attention, and this entitles the mail to the services of a

physician and the supply of medicine during illness, aa well as entry

into the C0mp-ho3pital with attention in cases of accident. The outlay

over and above these two sums is governed entirely by the caprices and

temperament of the worker. Clothes made for wear, ami not appearance,

are the order of the day; alcoholic drink, except in very few instances,

is not to be obtained for love or money except surreptitiously and

illegally, owing to the prohibition law, so that the worker cannot

fritter away his money in excesses. Tobacco is practically the sole form

of enjoyment, unless one except cards and gambling, which, for some

inscrutable reason, appear to be inseparable from the Canadian navvy's

life.

The navvy’s existence,

taken on the whole, is enjoyable. The men aro not so isolated or lonely

as one might imagine at first sight. The railway camps are strung out

over a distance of 100 or 150 miles, and are about two miles apart. Each

little community may number from forty to 200 souls or more. The

buildings, are as comfortable as massive logs and moss-chinking,

together with the assistance of a wood-burning stove in winter can make

them. The bunk-house is snug, with the beds cr bunks set out in a row on

either side of a central gangway and in two tiers. The mattresses are

composed of thin willow-poles laid longitudinally, covered with a thick

layer of balsam boughs or loose hay and blankets. At one camp the

contractor indulged the men to an extreme degree. The bunk-house was

equipped with single iron bedsteads and blankets, while a special man

was deputed to attend to the sleeping accommodation and the drawing of

hot and cold water for washing purposes, so that when the men returned

at night they might be able to perform their ablutions without having

“to pack” the hot or cold water. This, however, was an extreme

exception.

The men are torn from

their slumbers about six o’clock in the morning by the clanging of the

cock's gong—a triangular piece of steel fashioned from a bar about an

inch in dir meter, beaten with a steel rod. Tumbling out of their

berths, the men hurriedly don their attire, and, armed with soap and

towels, scurry away down to the creek, beside which the camp is pitched,

to have a wash in the crystal refreshing water. Violent drubbing with

the towel brings a healthy glow to the cheeks, and then there is a

scamper into the dining hall, which is another log-dwelling, to do

justice to a substantial meal. It is safe to say that very few navvies

in the Old World can point to such good square meals as their comrades

receive in a Canadian railway-camp. There is a round of oatmeal or mush,

followed by meat and vegetables in plenty, with a wind-up of pie in

variety. Without the mush and pie no Canadian navvy would think of

starting out upon his day’s work. Pork and beans; invariably figure on

the menu, as they form an excellent support to Little Mary when the toil

is hard and exhausting in the rock-cut or the sand-pit.

Breakfast finished, the

men scatter to their stations on the grade, and by the stroke of seven

have bent their backs to their jobs, continuing without interruption

until midday. The blare of whistles precipitates a stampede to the

dining-room once more, as the keen virgin air and the grinding work

produces a big appetite, which is assuaged by bowls of steaming soup,

with a following of meat and vegetables, pork and beans, or fish. Stewed

fruit and rice, the inevitable pie, bread in plenty, and cheese help to

provide a substantial foundation for the afternoon’s work, which is

started at one o’clock.

There is another five

hours’ pull with the tools until the screech of the sirens at six

o’clock sounds, cessation of work for the day. The men, as a rule, have

a good wash and brush-up on the banks of the creek, and then file into

the dining-hall for the third and last meal, which, in point of variety

and substance, compares with the midday repast. The camps are well

stocked with provisions of a most assorted character, which, though

canned, are invariably of a most tasty description. The only liquors

permitted are lime-juice, which is drank liberally to nullify the

effects of the preserved comestibles impregnated with salt, and thus

tends to counteract the chances of an outbreak of scurvy, together with

tea and coffee ad lib., with as much sugar and milk as fancy dictates.

The meats are not

exclusively of the canned variety, however. These are regarded more in

the light of reserve provisions. When the camps have settled down

steadily to work, facilities are provided whereby the men are insured a

steady supply of fresh meat, cattle being driven along the route and

killed at suitable points for distribution among the scattered

communities. In one instance the builders of the Grand Trunk Pacific

Railway contracted for the supply of no less than 5,000 head of cattle

in the course of one year. These animals had to be driven in huge droves

for over 600 miles across country to the most central point among the

camps. On the Skeena River the contractors set up a large

slaughterhouse, and the meat as dressed was conveyed down the waterway

to a cold storage, which likewise was specially erected to hold the food

in plenty for distribution wherever required, so that there was little

possibility of the men running short of fresh meat. The contractors have

learned from experience that a good meat diet is essential to enable the

labourers to withstand the bard gruelling of five hours’ steady and

unremitting toil, throwing earth anti rock about to make way for the

parallel bands of steel.

When a camp is

established, as a rule the community can rely upon being settled there

for eighteen months or two years. The grade is driven outwards from the

camp on each side to meet the highway similarly driven from the adjacent

camp on either hand. Under these circumstances the men can add to their

diet by growing vegetables and ingredients for salads, which form a

welcome change to the canned articles of diet. As a matter of fact, a

large lumber of men turn their leisure time to cultivating small patches

when the soil is suitable, and the succulent lettuces, spring onions,

and radishes arc devoured with ill-disguised relish.

After the evening meal

the men while away the time according to individual inclinations. As a

rule, a couple of hours are beguiled in lounging, reading, and smoking,

or indulgence in some hobby, the arrival of nine o'clock seeing the

majority making way to the bunks for a well-earned rest.

Sunday is a blank day,

the one day’s rest in seven being rigidly enforced, except when

rush-work such an the building of a steel bridge which is holding up the

advance of the track-layer, is necessary. In the morning the banks

beside the little creek are busy with the navvies carrying out their

laundry duties, for every man has to complete his own washing, which,

although not extensive is yet imperative in the interests of health—that

is, if the wage-earner is alive to the advantages of hygiene. In the

afternoon many will wander off to visit pals in other camps, go out on a

hunt for “bar” or any other game in the forests, while others, with a

rod fashioned from a willow-branch, a few feet of cord, and a hook, will

ensconce themselves in shady nooks to indulge in the Waltonian art.

Visitors stray in from neighbouring camps, and around the camp fire peak

of laughter will ring out over anecdotes and reminiscences. The average

grader is a born raconteur, and many and varied are the stories which he

can reel off concerning his own experiences or those of people whom he

has mot. Then various institutions, such as the Young Men’s Christian

Association and Bible Missions pursue active campaigns for the

improvement of the mind, not with vapid discourses upon the differences

between heaven and hell, or an endeavour to lead the rough diamonds from

the latter to the former upon orthodox principles, but in homely talk in

which religion is well veiled. Sometimes a “frock” attached to one or

other of the various denominations will appear in the camp and will make

a special pleading for some purpose or other. Such strangers invariably

meet with a hearty welcome, especially if they are expert in preparing

the mental pabulum for such strange flocks. The services are as unlike

those connected with religious enterprises as it is possible to imagine.

The shepherds for the most part have a wealth of stories which they

relate, seizing every opportunity to drive home the moral unconsciously.

If the preacher is a “great stuff,” his work will not be in vain, for

the navvy is hearty and liberal in his response to the call for

financial assistance. Woe betide the grumbler who displays hostility to

the collection-plate, or is niggardly in his contributions thereto. His

comrades have their own way of bringing him to his senses, and making

him see eye to eye with them in supporting the preacher's claims.

Of course some

temperaments cannot be held in check; the prohibition law hits such

worthies hard, as it means that they have got to make a weary and

expensive journey of perhaps 200 miles to gratify their desires for a

carousal. They set off with a substantial wad of dollar bills

representing several months hard-earned wages, strike the nearest

licensed town, paint it red the first night, get pitchforked into some

dive by the human vultures always on the sharp lookout for such prey,

are robbed of everything, and then are compelled to return to the scene

of their former labours as best they can, probably borrowing the

wherewithal from the contractors to regain the camp, and having it

deducted from their wages when the latter are due.

Yet steady workers have

no difficulty in improving their positions. There always is room higher

up if a man has the capacity to occupy the vacant post. I have met

several who started picking and shovelling on the grade at two dollars a

day, but who soon climbed the ladder to become timekeepers at £14 per

month all found, foremen, and so on. Sir N. D. Mann is a case in point.

It was not many years ago that he was gruelling on the grade and

tumbling sleepers about for less than two dollars a day; now he is one

of the moving spirits in the third trans-continental railway. Many of

the contractors handling large jobs in the West, when they grow

reminiscent, will relate how they struggled hard at the worst work on

the grade for a few shillings to eke out a miserable existence as it was

then.

As a matter of fact,

there is no reason why a navvy should remain a mere navvy if he has any

initiative and pluck, as well as being thrifty. A few months’ work and

its accumulated equivalent in coin is a positive stepping-stone to

better and more remunerative occupation. The contractors are always

disposed to let out stations, as the lengths of 100 feet into which the

grade is divided are termed, on contract or piece-work. They let the job

tor a certain price, and their profit is represented in the difference

between what they receive for the task and what they pay the

piece-worker. A man with less than £lo can get a start as a

subcontractor. He will either recruit his labour himself, paying the

usual wage, or in turn will put his men upon piece-work rates, and will

take a hand in it himself. Maybe the station is easy, requiring

practically no plant beyond a few planks, picks, shovels, and

wheelbarrows. The chief contractors will let out these requisitions to

him at a low rate. The subcontractor can only hope to make the job

remunerative to himself by getting it through at high pressure, and he

accordingly spares no effort to bring about such a consummation. A man

toiling on piece-work will put more effort into ten hours than a man who

is content to draw a day’s pay, and without any ambition to better his

position. Accordingly, the contractors foster “subbing.” It means that

the job is completed in shorter time than is possible with day labour,

and it is immaterial to them how much the subcontractor makes or loses

over the job, so long as it is carried out in accordance with

specifications. The Scotsmen are particularly keen upon subcontracting,

and many working upon the co-operative principle to complete a station,

have cleared substantial sums as a result of their enterprise.

This tendency is

responsible for reckless plunging at times; the man thinks that he can

see his way to make a good thing out of a station or two, and although

it may involve the laying out of perhaps several hundred pound;! in

plant, he will embark cheerfully upon the enterprise with a capital,

perhaps, of only £30 or £40. If fortune i3 kind, and he works hard, and

knows how to set about the task, he pulls through all right and smiles

satisfactorily as he draws a fat cheque and weighs up the balance

representing profit on the transaction. If he comes a cropper, he turns

over the unfortunate station to the contractors and resumes work at a

daily wage until he has amassed a few more pounds, with which to feel

his feet and try his luck anew.

Subcontracting does not

involve the quotation of a lump sum for the completion of a station.

Such a system is impossible, as no one can tell what is lurking beneath

the surface of the ground. Maybe what looks like soft soil may spring a

surprise in the form of slippery clay, or dense rock, demanding skilled

labour for blasting. The subcontractor works upon the payment by cubic

yard basis. The engineers have plotted the path of the line, and it

demands the removal of so much material to fashion the pathway, either

from the spot to drive a cutting, or from a ballast-pit to build up an

embankment. The debris is divided into three ratings. Ordinary soil is

classified as “common”; earth associated with stones and small boulders

as “loose rock”; while that requiring the aid of explosives is known as

“solid rock.” The first named receives the lowest payment because it is

the easiest to handle, and requires practically no tackle; the latter

receives the highest pay, as it demands first-class skill in boring and

handling the explosives, while the second named receives a price between

the two. The subcontractor’s work is measured by the engineers, who also

decide what is essential to this end in accordance with the

specifications, and for this total the1 man is paid. If he has removed

too much spoil, then his labour has been in vain, and he must pocket his

loss; this is practically whore the risk comes in, especially in rock,

but if a mar. is careful he will not err on the side of doing too much

work; it is his own fault if he does.

The winter is possibly

the worst period for the navvy; then he is often imprisoned virtually by

an encircling wall of snow-bound forest, more effective as a barrier

than steel bars. With the thermometer down so low that to pick up an

iron bar with the naked hand is to produce a blister, and with the blast

so keen that it cuts like a knife unless furs and woollen clothing are

liberally donned, it requires some pluck to rally out into the rock-cut.

In these islands

navvying is regarded practically as being on the lowest rung of human

endeavour, but in the Dominion, where the moulding process is still

being actively pursued, the navvy is regarded as an indispensable unit.

Without him the foundations of the country cannot be laid, and for this

very reason the task is regarded as a positive stepping-stone to better

things, provided the wielder of the pick and shovel has an average

amount of enterprise and brains. As a matter of fact, although he may

arrive in the country with no more ambition than a tramp, this faculty

soon becomes kindled and developed under the spurring effort of his

pals’ successes, so that he labours to attain greater heights on the

ladder of success himself. |