|

If one desires to get a

real taste of Canadian life as it was known half a century or more ago,

and to indulge in pioneering work, with all its excitement and

fascination, as well as being able to take money quickly, then the

frontier town is an ideal centre. There is something peculiarly

magnetizing about a small community surveying the even tenor of its way,

and working out its own destiny, two or three hundred miles away from

the click of the telegraph and the throbbing of the railway locomotive.

Under such conditions unique opportunities open up for the display of

ingenuity and master-strokes of policy, whilo the chances for making a

good deal are without a parallel.

The men who establish

those remote new towns are a people apart. They are the slowly

disappearing remnants of that race who tamed, not only the wildest parts

of Canada, but the most inaccessible comers of the United States as

well, in the da3Ts when railways remained to be built. They are sturdy,

self-reliant, and happy-go-lucky specimens of humanity, taking long

chances, and never so content as when they are severed from

civilization’s apron-strings. Town-building is their hobby, and when at

last the railway and telegraph creep up to the front-door, these

worthies steal oxE through the back portal, trek across country, select

another attractive isolated site, and once more set to work at rescuing

a tract of bush from primevalism, and turning it into a throbbing Live

of activity. I struck one frontier town far removed from the railway,

which was going ahead with amazing speed. Down at the lower end of the

main street two waitresses were catering for the needs of the pioneers.

They came up with the first wave of invasion, when the builders of

Empire were still engaged in razing the forest to the ground to make way

for the streets and buildings of the metropolis of to morrow. How they

got up no one seemed to know, but they had roughed it considerably in so

doing. When they reached their destination they took over a shack

recently completed, at a nominal rent, with the option to purchase the

freehold by instalments. They laid out the whole of their slender

capital to advantage, and on the first morning they opened up for the

benefit of the town at large they served 175 meals at 2s. per head. The

first day netted them a gross return of nearly £50, and although the

majority of the customers had to sit upon the ground outside, with their

plates between their crossed legs, and had to provide their own cutlery

in the form of the indispensable jack-knife, using fingers as a fork,

nobody grumbled. It was characteristic of the life. Those two girls

never looked back. At the end of the first month they had acquired the

freehold of their premises, paying off the purchase price in a single

instalment, and the bank up the street could point to a good balance in

their favour or the right side of the profit and loss account.

When I reached the town

after a prolonged imprisonment in the wilds with the pack-train, my

hirsute appendage would have been envied by the most popular virtuoso.

But, unlike the latter, I was anxious to rid myself of this decoration.

There was a tonsorial artist in Main Street, and in company with my

companions who were burdened with a similar superfluous adornment, we

tendered our custom. The artist was out. He was nailing down floorboards

for a fellow-citizen at two shillings an hour over yonder, but would lie

back later, as his Chinese underling explained. We returned in an hour,

but with little success. The barber was busy fixing up a watch, the

mainspring of which had gone awry, while the other mechanical parts of

the timepiece were unable to operate owing to the presence of dust. We

waited. At last the artist appeared on the scene, and we were shorn at

4s. a head. That harbor knew no more of hiss craft than a mouse does

about running a cheese factory. He might have tried a hand at clipping a

horse, and would have done himself better justice. At all events that

was the only hair cutting tool about which he knew anything, and in

about ten minutes he turned us out of his shack, with heads so cleanly

shaven that had we been at homo we should have been held up as escaped

convicts. He had offered to give us a shave, which we needed sadly, but

the experience under the clippers caused us to apprehend the

manipulation of the razor with ill-concealed trepidation. Floorboard

setting, hair-cutting, and watch-mending appear to be a strange

combination of occupations, but the man was meeting with success.

Hair-cutting was slack during the day, so he was quite ready to improve

the vacant hours in any other industrial direction for which there might

be a demand and adequate remuneration !

The storekeeper

flourishes excellently. He has the entire population at his mercy. If

one is dissatisfied with his goods and exorbitant charges, one must

order requirements through the post from, some cheaper provider in the

great cities. But the mail facilities in a frontier town are as

uncertain as an English season. It might be a month or it might be three

months before the goods so ordered would reach their destination. The

local shop keeper is fully aware of this fact, and so is able to assume

the position of a dictator. When a rival appears upon the scene there is

no competition between the two. The twain promptly meet, and over a

bottle of illicit whisky complete a mutual arrangement to maintain

prices for the various commodities.

When I struck the

booming town of Fort George in its earliest days, I found 320 energetic

souls pushing ahead 320 miles away from the railway as if the latter

were only 320 feet distant. Everything was at famine prices, hut I had

scarcely jumped out of the canoe when a citizen, pausing in his work,

looked up and asked if I would give him a hand. He offered 25s. a day,

but I declined. Without the slightest hesitation he sprung another 5s.,

and could give me three weeks’ work right off! Wages equalling £10 10s.

a week for the most unskilled labour was certainly enticing, and he was

dumbfounded when I shook my head negatively, until 1 explained that I

was on different business bent. He laboured under the impression that I

was looking for work. Here floorboard-bashing, comprising not only tho

nailing down of flooring, but also the erection of side-walls, roofs,

and internal fittings of a timber frame building was the prime

occupation, followed hard by others of a most diversified character. The

population for the most part was recruited from ranks of sourdoughs, who

had tasted the sweets and acids of the famous gold rush to the Klondyke;

Blaguay, Dawson City, and White Horse were mentioned quite as frequently

as Fort George.

The ground-floor

tenants of Fort George had made history. About 155 miles of waterway and

103 miles of the Cariboo road cut them off from the nearest

railway-station— Ashcroft on the Canadian Pacific. When the first rush

started, the stampeders walked, drove, or rode astride a pack-horse over

the stretch of paved highway, and then came up the river ad best they

could under Indian guidance in canoes, with the Red Men netting 15s. a

day or more for their trouble. The population of Fort George concluded

that they were being held up too tightly by the Indians, so, without any

tackle incidental to the task, they set to work to build a

shallow-draught steamboat, launched the hull, installed the requisite

machinery, and soon regarded with great satisfaction the result of their

handiwork. That solved one part of tho transportation problem. Then came

another. The traffic along the Cariboo highroad was by team-waggon, pack

-horses, and by archaic stage coach, reminiscent of the fifties of last

century between San Francisco and Salt Lake City. This vehicle demanded

two days to travel between Soda Creek and Ashcroft. As Fork George

prospered and boomed larger and larger in the public eyes, the

supercession of horse-traction was demanded. The agitation was met.

Motor-cars wore introduced; even then the travelling citizens were not

satisfied until these were speeded up so as to reel off the 163 miles in

about eight or ten hours. It was worth risking the safety of the neck to

save a day in travelling between Fort George and Vancouver, the nearest

city.

Life in a frontier town

is what the inhabitants make it. In the early days the community is a

large family; everyone knows everybody else, and one and all put

together to mould the town and to evolve amusements to while away the

hours which must be passed in enforced idleness. Practical joking is

very rife, although at times it threatens to terminate tragically. One

season the Fort Georgettes were marooned. All the boats had come to

grief by fouling the rocky teeth in the bed of the Fraser River.

Provisions ran short, and the people became anxious about the future.

Whether the steamers had been repaired and were coming up the river or

not no one knew. The town had no telegraphic communication with the

outside world by which to glean any such tidings. Every evening crowds

made their May to the point where the steamers hitched up alongside the

tank, and peered anxiously down the waterway, while rumours fell as

quickly as leaves in autumn.

The whole community was

strung to a high pitch of apprehension. It could not hold out much

longer. Ono evening there came echoing up the waters of the river the

long-drawn-out hoot of a siren. It was the steamer ! Everyone ceased

work and scampered down to the waterside. The hoot was heard again, and

then came a long, long silence. The excited people waited and waited,

but the expected steamer did not heave in sight. While one and ail were

speculating whether the steamboat had come to grief in its last two or

three miles of water journey, there was anothor hoot, and a dugout crept

round the bend of the river, with a Siwash poling desperately, and one

of the townsfolk standing up blowing a horn for dear life! He had

conceived the idea of startling his fellow-citizens into excited frenzy.

As he crept towards the town he was assailed with a volley of threats

and abuse, but he wisely hugged the opposite bank, and did not land

until the temper of the Fort Georgettes had cooled down sufficiently for

them to realize that they had been hoodwinked.

Port George gained

fleeting fame as a goldfield. It happened in this wise:

When the early-risers

came down Mein Street one morning they rubbed their eyes in amazement.

There, on the vacant lot beside the baker’s shop, was one of the most

respected citizens, sedulously washing with a gold-pan. They thought he

had gone crazy, but when they went up to him he mutely showed his pan,

and the little specks of colour mingled with the muddy silt. They

examined it closely. Gee! It was gold, and the panner pointed

significantly to the ground. In the twinkling of an eye all Fort George

had gone gold mad. Vessels of all descriptions were rummaged up to serve

as pans, and, with cans and jugs of water, the populace fought in order

to get on the small vacant patch. In less than half an hour it was

overrun with a mob, digging, shovelling, and panning, as if their

existence were at stake. The baker came out of his shack, and in broken

German, for he was a stolid Teuton, wanted to know what the “Teffel they

vare doin’ mit his home,” for the excited gold-seekers were undermining

his dwelling, and he feared that every minute would bring about its

collapse. But his frenzied dancing and wringing of hands were of no

avail. The gold-fever had broken out with its characteristic virulence,

and the gold-seekers did not care if they tore the baker’s shop to

pieces so long as they succeeded in their quest.

There were two men who

seemed blind to the golden chance. They lounged around extending advice.

The excitement culminated when one of the citizens bravely produced his

miner’s licence, and gravely announced to one and all that he claimed

the whole lot in accordance with the term of law! As he was the only man

present possessing a licence, he was perfectly right in his action.

After staking his claim he announced that he was off to Vancouver to do

a deal with it. The twain who had been so liberal with suggestions gave

vent to an unbridled shriek of delight, and then hurried away to their

shack, where the rafters rang with their loud guffaws. Suddenly one of

the gold seekers stopped panning, returned to his senses, and blurted

out his opinion that the lot had been salted, and that they had been

fooled! Everyone recalled then that the twain who had been so ready with

advice had been to the Klondyke and had small bags of dust. They

surmised, as was, indeed, the case, that they had mixed their dust with

the sand, and that the man first seen panning was in the joke. The

bubble was pricked; one and all departed sadly from the scene. Thus the

Port George gold-rush petered out, but the three men who had fathered

the enterprise were prostrated with mirth the whole of that day at the

success of their scheme to liven things up.

Once a week the

citizens had a night off. In other words they participated in revelry of

the wildest description. It started off soon after dusk. The members

gathered together, and Terpsichore ran riot in the street. When they

tired of doing the light fantastic they bawled out the latest comic

songs at the tops of their voices to the accompaniment of the wildest

musical instruments, and the result was a good imitation of an Indian

pot-latch or tribal feast. If any member of the community had given

popular offence during the previous week, he was repaid on this

occasion, all the town turning out in force against him and obtaining

reprisals. I recall one incident while I was there. A certain land

speculator had called down the wrath of the smal1 population who did not

regard his methods with favour. He had dragged the fair name of rising

Fort George through the mud, so they said, and confidently believed. So

one night everyone decided to take revenge en masse. The town was

paraded; every notice and advertisement of the offensive speculator was

destroyed. As the streets were unenlighted and practically the whole

town was wrapped in darkness, the attack was successful. In the morning

the offending property presented a sorry sight, a dismal scene of

wreckage, extending to over £100 in value. The aggrieved speculator

promptly offered a reward of £20 for the apprehension of the

ringleaders, but he is still searching for them.

It is impossible to

curb these wild spirits. The pioneer had a strange temperament, and is

offended by the slightest deviation from the “square deal.” The

community working hand in- hard has its own code of honour, and by

pulling together there is no need for the majesty of law and order in

the form of police, crime is unknown or if it should break out, is

suppressed instantly by fellow-citizens, the offender being compelled to

seek safety in flight. Tie majority of these frontier towns are within

what is known as the “Dry District”—that is to say, alcoholic liquors

are forbidden to be sold and drunk by the Inhibition law. Yet there are

many knaves who stoop to any subterfuge to smuggle in liquor and to

dispose of it surreptitiously. If the genuine article cannot be

obtained, then they do not hesitate to brew hideous concoctions from

fruit-juices and nicotine, which is colloquially known as “raw-cut,”

while the establishment at which it is made and sold is the “blind pig.”

In Western Canada the North-West Mounted Police have their own ways and

means of dealing with this despicable individual, and they do not

restrain their hands when they catch a “blind pig” in full swing. The

proprietor is fortunate if he gets off with a fine of £10, a warning to

“get out.” and the pounding of his stock-in-trade to fragments. He

generally follows the advice to make himself scarce, because if he

remains behind he is certain to be a marked man, and always to be under

suspicion. A second offence may moan exile or imprisonment for a long

term, and ho does not consider the illicit traffic to be worth this

risk.

In the town which I

remember drunkenness was very rife at times. The well-ordered members of

the community stood aghast at this trend of events. A meeting was held,

and the outcome of the conclave was the issue of a general warning that

if the persons or person responsible for this deplorable condition of

affairs were caught, and summary punishment would follow. But the “blind

pig,” secure in his concealment, laughed at the dire threats of

vengeance, until one night he was rounded up. The citizens took the law

into their own hands, and the spokesman of the town looked prim and

ominous. The “blind pig” was dragged out in an unceremonious manner,

amid cries of “Pitch him into the water.” He squeaked and shrieked

terribly at the prospect of modified lynch-law being practised upon him.

The internal arrangements of Ms shack were tumbled oat into a heap in

the roadway, and four cares of whisky were brought to light, together

with a large quantity of “raw-cut” in various stages of manufacture. The

whole lot was destroyed. Over £50 worth of liquor mingled with the dust,

and the proprietor struggled and kicked as he saw his stook-in-trade

vanishing so unceremoniously. The crowd stuck to their man all night,

and the next morning he was hustled out of the town amid general

execration and howls of what he would get if caught there again. He was

only one offender, but the treatment meted out to this illegal tradesman

sufficed to bring about the demise of the remaining “blind pigs” from

fright.

In the rising town,

however, there is practically an opening for every class of human

activity, and if success cannot be struck in one vein there is always

the chance to fall back upon another career. The lard around the centre

beeomeb opened up, giving scope for the agriculturist; the demand for

timber brings about the establishment of timber-mills; machinery of all

description is soon in urgent request; and when at last the railway

creeps in golden opportunities are presented to the man with a little

capital—he has a virgin and uncompetitive field in which to invest his

savings.

I have had many

glimpses of the frontier town, and as a vortex in which to make money it

eclipses completely the hording city boasting a history of centuries.

The population of the whole place may not number more than 100 persons

all told, yet one and all are as busy as bees from dawn to dusk putting

the place shipshape in readiness for the arrival of the railway or

steamboats. There are no drones in such a spot; the wheels of progress

must not be braked. Labour is at a premium.- and, accordingly, one has

to exercise brawn and muscle in some job or other every day without

ceasing. If the work-shy attempted to thrive in such a community, he

would starve. Provisions generally soar to high prices, as a weary trek

over 200 or 300 miles of rough trail on the backs of pack-horses or in

small canoes is costly, and often enhances the value of an article to

four or five times its intrinsic value. Difficulties of transportation

are responsible for sending bread to Is. a pound loaf, butter to 1s. a

pound, eggs to 6d. or Is. 6d. apiece, tea, coffee, and other necessaries

of life to equally exorbitant figures. The poor man cannot live in a

frontier town, and, in fact, he is quite an unknown genus, because there

is no reason why a man should be poor within its limits.

Though provisions soar

almost to famine prices, wages are commensurately high. Unskilled labour

can command from 20s. upwards per day. I have seen as much as 50s. per

day offered to an English carpenter, and refused. The jack-of-all trades

is in his element, and probably occupies the only notch in this world

that is to be found for him- The artist of craft is not required.

Everything is in the rough; the aesthetic tracery comes later when the

town has shaken down to its position in the world’s affairs. A man must

be prepared to do anything, and the nature of his task may be varied as

many as nix or eight times during the single day.

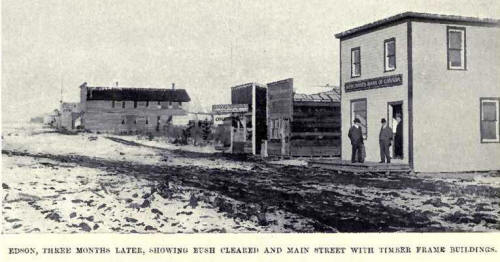

In the early stages, as

may be naturally supposed, building is the absorbing occupation, because

new arrivals must be housed, and shops must be opened to meet the

thousand and one requirements of the townsfolk. The buildings, however,

are rough timber frame structures, where fine work is not desired, and,

indeed, is wasted energy and ability. The logs are hewn up roughly down

at the saw mill, and as they arrive are rudely used to the joist

supports in the unplaned state. Work of this character does not demand

an experienced carpenter. Anyone can do it, and can make from 15s. to

20s. per day at the job, according to the state of the labour-market, in

which the demand generally exceeds the supply.

What becomes of these

hardy pioneers, who risk life and limb and brave hardships untold in

stirring the melting pot of civilisation and moulding the fabric to form

new cities? The end is in harmony with their life; is a fitting

conclusion to an existence devoted to grappling with the forbidding

wilderness. When at last their work is done they find a quiet

resting-place beneath a sheltering tree, under the guardianship of a

crude cross, and with a rude picket fence railing off their last 6 feet

of Canadian freehold. |