|

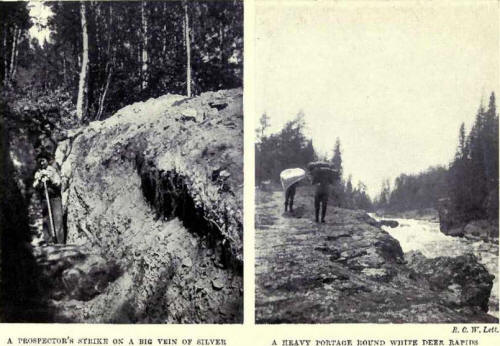

The prospector is the

epitome of honesty. When he strikes a town in the mineral area generally

he is empty in pocket or else his purse is slender in the extreme. Yet,

once his bona fides are established, he is extended almost unlimited

credit, the tradesmen knowing full well that when metal is struck their

accounts will be settled. Many strange worthies of this character may be

mot in British Columbia. There was Archie McMurdo, for instance. A

Scotsman, he was canny to an extreme degree, although he “was broke to

the wide ” when ho came into the town. He had devoted the greater part

of his life to scratching the rocks on the mountain slopes, and success

had attended his perseverance. He staked two rich gold claims. Satisfied

with this measure of success, he returned to the adjacent township to

pass his time in indolence and ease until financiers, came his way and

took over his properties, as he knew would be the case sooner or later.

He would not do a stroke of work; he disarmed of the wealth in the air

which was to materialize. Although he eking to his claim for ten year.

without a sign of development materializing in the meantime he never

grew down hearted.

One day some mining

experts, acting on behalf of financiers who had heard of Archie’s

finds—he took good care that attractive stories as to the value of his

prospects should be sedulously circulated—appeared on the scene. They

were desirous of investigating the McMurdo claims. Archie, as usual, was

ran to earth in the hotel where he had been living gaily and had not

paid a cent for years. Everything he had was written upon the slate, or

rather in a good-sized account book. The mining experts expressed their

intentions, and requested Archie to accompany them.

“I’ll see you to blazer

first!” replied Archie.

“But, man, we cannot do

anything unless we see what, you’ve got,” replied the experts.

“I dinna care,” was

Archie's retort. “Unless you plank down a hundred dollars for my

expenses, and deposit spot cash in the bank to be handed over to me when

you come back, I’m not going. I’ve spent too many years among those

darned mountains to go there again on chance.”

Argument was useless.

The money he demanded had to be deposited, and then he sallied off to

lead the experts to one of his claims. It was far up on the

mountainside, and when they reached the bottom of the trail he told the

experts to go ahead. He would wait for them.

“But you must come and

show us the place,” urged the engineers.

“No, not me! I'm not

going to pull up that slope any more. There’s the trail which I cut

myself. It leads straight to the spot. You can’t miss it, so I’ll sit

down here and wait until you come back.” Saying which, he planked down

on a dead fall and puffed away at his pipe as if the engineers were

miles away.

Having come so far, the

latter did not care to return without having achieved their object. They

could not shake Archie’s obstinacy, so they went alone. He waited

patiently for hours, and upon their return inquired if they were

satisfied. They responded in the affirmative, and Archie accompanied the

party back to the town; highly elated. He went straight to the bank,

and. drew out the £1,000 that had been deposited for his property. He

sailed off to the hotel, called for his account which had been running

for ten year&, and settled it up without a murmur. Then he strode up the

street, and. entered the store where he had obtained unlimited credit

for an equal length of time. It was no easy matter to tot up his debts,

for they occupied a few score pages. But at last the bill was presented,

and, without scanning a sheet, Archie paid the amount. He then returned

to the hotel, completely satisfied with the world at large, and called

for drinks.

His claim was opened

up, and its success prompted another group to approach him for his

second claim. The party were met just as nonchalantly. Archie explained

its position, related how it could be reached, and told the engineers to

start off right away. When they suggested that ho should come along too,

ho laughed them to scorn, and told them point blank that if they

couldn’t find their way with the instructions he had given them, they

had better go back home and leave the claim alone.

Unfortunately, the

rigours of exposure among the mountains, combined with excesses in the

town, had undermined McMurdo’s constitution. He was stricken down with

illness, and was hurried off to the hospital. On the last day of the

year the second claim matured, and £10,000 were handed to the rugged

prospector. But he never saw a penny of it. On the following day he

succumbed, but he died with the satisfaction that he did not owe a

farthing to anyone.

The vast tract of

wilderness north of the Fraser River stretch ing away to the Arctic

circle, but especially in the watershed of the Peace River, is

associated with much yellow wealth. It has been difficult of access

hitherto, but penetration is becoming easier every day now, owing to the

construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

The Pine River has been

the scene of mining bustle in the past, for the river bed is rich in

colour. The gold-bearing area extends over 100 miles, and miners using

primitive rockers have wrested as much as £3 to £4 worth of gold per day

from the silt. A few miners are to be encountered along its banks

to-day, but its attraction appears to have disappeared. The gold is

worth panning, the metal being in heavy flakes like fish scales, while

in some places quite largo nuggets have been found. The working season

extends from March to October, and certain success attends the

industrious, despite the remote situation of the territory. As the Peace

River country is being settled so rapidly, however, it is probable that

a large number of prospectors and miners will force their way into the

country. It should be a promising undertaking for some energetic

prospectors to trace the part from which this gold is brought down, and

undoubtedly many of the creeks and rivulets feeding the Pine River, and

which rise high up on the mountain crags, would repay exploration. At

the present moment the installation of a dredger should be remunerative

upon this 100 miles of the river. I have been told that such could bo

transported and launched upon the waterway for between £30,000 and

£40,000, and that men competent with such means of extracting the gold,

could make from £5 to £8 apiece per day in wages, doing as much work in

that time as from 800 to 1,000 men with pans and rockers.

The fascination of

prospecting is its glorious uncertainty. One never knows when a strike

is going to be made. There was one coal prospector who had made a study

of the eastern Rocky Mountains coal bed. One day he suddenly announced

his intention of setting off towards Jasper House on the Athabasca

River, to continue his investigations. It seemed a hopeless quest,

because geological knowledge was dead against him. The prospector,

however, had elaborated his own ideas, and he started out. He commenced

operations on the southern side of the river, and he had not gore far

when he struck a rich seam of coal. He probed the country through and

through, and found coal of excellent quality on every hand. As a matter

of fact, he struck one of the finest coal deposits in the West, and

development more than confirmed his prospects. I was taken over the

preliminary works, and the whole mountains seemed to be alive with the

black mineral fuel. Before the prospector had completed his work,

thirteen square miles of land were pegged off for operations, and

geological knowledge was scattered ruthlessly to the four winds. To-day

the Jasper Park Collieries give every indication of becoming one of the

largest and most valuable coal properties in the West.

Yet this discovery was

but a repetition of experience in connection with Cobalt. Geologists

laughed at the mere Idea that silver was likely to be found in thin

district. Why, the very character of the rocks was all against such a

probability! How far geological science was correct one can judge

to-day, because two-thirds of the world’s supply of silver comes from

the very country which was ridiculed as being unable to yield an ounce

of silver.

It is stated that the

Cobalt mineral wealth was discovered by accident. Legend relates that a

deer was being hunted through the bush. In its mad flight it passed near

a blacksmith’s shack. The son of Tubal Cain was at work as the deer

passed, and he flung his heavy hammer at the frightened animal. The

missile missed the target, but struck a large dull-looking stone,

breaking off a fragment. The blacksmith went to pick up his hammer, but

in stooping, noticed that the stone gave a brilliant lustre, where it

had been chipped. The boulder was picked up, and further investigation

revealed the fact that it was a maws of silver!

It is a pretty story,

but as a matter of fact the discovery oi tho metal was stripped of such

romance. The wealth was found during prosaic prospecting by an

industrious individual who cared little for scientific opinion. When he

struck the silver veins, a frantic rush ensued, and in a few weeks, what

was a picturesque sylvan f pot in the beautiful Temagami country, was

stripped of its bush, and was dotted with tents and hastily-built

shacks.

Fortunes have been won

and lost at Cobalt by the score. One man was anxious to get into the

country, but he had not the wherewithal to pay his railway fare farther

than North Bay. He did not cherish the prospect of walking 200 miles, so

he “beat” the train into the country. He landed in Cobalt without a

penny in his pocket. When he returned south, he travelled not on the

roof exposed to the elements, but in the luxury of the Pullman

drawing-room car. Another prospector came into Cobalt with £00 in his

pocket, and having had wide prospecting experience among the mountains

of British Columbia, he soon turned his original capital into between

£40,000 and £60,000. Some of the big finds in Cobalt have been made

quite by accident. Outside one shack a plank-seat was supported on two

largo boulders. One day an occupant of the meat was idly sharpening his

jack-knife upon one of the masses of rock. Presently he became intensely

interested in the stone, and submitted it to a closer inspection. The

ungainly mass of rock supporting the seat turned out to be a silver

nugget weighing over 1,000 ounces and worth about £400.

The prospecting and

gold-camp of to-day is vastly dissimilar from the hotbeds of debauchery

and crime pictured by Bret Harte. As a ride they are fairly well ordered

communities, thanks to the action of the forces of law and order. Such

tricks as jumping claims are very seldom practised; in fact, they are

practically unknown. The miners are guarded by the Government, through

their licences, which cost but a small sum per year, and these provide

complete protection, as well as affording other benefits.

The wonderful

discoveries of the Klondyke precipitated possibly the greatest rush in

Canadian history. Though the easiest route was by water from western

coasts port to Skaguay, many were lured into the effort to toil 4,000

miles across country from Edmonton. The fever broke out in this town

with tremendous virulence, and some of the strangest vehicles it is

possible to conceive were delivered to carry the gold-seekers through

the most terrible country to be found on the continent. Some set off

with wheelbarrows, undeterred by the prospect of having to trundle the

same for such a tremendous distance, while large numbers set off on

sleighs. It was a disastrous expedition. The majority turned back,

abandoning their vehicles, provisions, and outfits to the mercies of the

elements. The trail was blazed for a considerable distance with these

discarded equipments. Some pushed on, desperately, determined to got to

their destination at all hazards. One prospector was found trundling a

wheelbarrow through the mountains some distance north of the Skeena

River two years after he had set out from Edmonton! He had lost his way,

his chum had died on the trail, and the survivor knew nothing about

time, days, or months. When found, he was pushing forward with more or

less energy. When he learned that he had beer, on the trail for nearly

two years, he gapped, but that did not deter him. Privation and

loneliness had almost deprived him of speech, and had dulled his

intellect to the point that he could not comprehend anything beyond the

fact that he was bound for the Klondyke and its gold. The hoys who found

him, only persuaded him to return to civilization with them by

impressing upon Lim the fact that the gold strike had “petered out,” and

that he was on a lost journey. Two miles a day had been his average

advance, and how he had contrived to cross the rivers single-handed was

a mystery which his rescuers could not fathom.

The discovery at the

Klondyke provoked a situation excelling in lawlessness any that were

incidental to the Californian gold-rush. Ore noted desperado ruled the

whole town of Skaguay. His avariciousness and crime knew no limits.

Before he was shot down, it is stated that over fifty prospectors and

gold-seekers had been sent to their doom after being robbed of their

hard-earned gold. His usual practice was to waylay them on the trail,

and to pitch their bodies into a canyon or gorge, where they were sale

from discovery. When challenged for having caused a man’s health, Soapy

Smith, which was the unpretentious name of this individual, always

replied that he shot in self-defence. In some instances such was the

case, and the desperado himself had many narrow escapes. One day he

waylaid a returning prospector on the mountain pass. The gold-seeker,

however, was not to be despoiled so easily. Ho met the hold-up with a

drive from his rifle, and the bullet went through Smith’s hat. A second

shot was impossible, because Soapy Smith pierced the prospector through

the heart. On another occasion he held up a young English fellow who was

returning to Skaguay. The boy did not take any notice of the challenge,

and Smith fired, knocking him over. The young prospector whipped out his

revolver, and blazed away at his adversary, twice wounding him slightly,

before the desperado settled the boy with his third shot. Smith was a

great anxiety to the Canadian authorities.

The Mounted Police were

stationed on the Boundary at the summit oi the Pass, and received strict

injunctions to arrest Smith if ho attempted any of his tricks on

Canadian territory. In Alaska, which was United States territory, he

could do as he liked or what was permitted —the desperado represented

law and order of his own peculiar formation—but at times he enraged the

honest citizens to such a pitch that ho had to make himself scarce for a

while. On such occasions ho hurried towards the Boundary, hoping to

snatch temporary asylum in Canada, until things quietened down in

Skaguay. But his efforts were fruitless : the Mounted Police always

frustrated his plans. Just as he was on the verge of stepping across the

border, he was confronted by one of these guardians of the Great West.

At last, the latter wearied of watching such a parasite. He was taken

quietly aside by one of the police, and told very significantly that “if

he were seen on Canadian territory he would receive more asylum than he

cleared with a bullet. They would not trouble to arrest and try such

carrion as him, as it would be waste of time and money.” Smith took the

hint, and was never seen to make another attempt to penetrate into

Canada. Shortly afterwards he was shot down by the infuriated townsfolk

of Skaguay, and the reign of terrorism was ended.

A graphic and intimate

impression of the adventurous life of the mineral prospector was

conveyed to me one right round the blazing camp fire, by my companion on

the trail, Robert C. W. Lett. When he broke away from the lonely calling

of game-warden in Algonquin Park, be embarked upon a prospecting

expedition. Two experienced companions joined him in this pursuit of

fortune, the projected field for their labours being one of the

innermost recesses of Ontario, which has since gained tame at the

Gowganda country.

The definite intention

of this trio was to find silver, if possible, though, of course, they

were quite ready and willing to stake out claims of any other commercial

minerals, should signs thereof present themselves. They started out from

Latchford on the Montreal River, just south of Cobalt, in the early

spring of 1907.

A steady 150 miles pull

along the Montreal River confronted them at the outset, and it proved a

pretty tough undertaking negotiating the fiendish rapids -with which the

upper reaches of this waterway abound, with two heavily-laden canoes,

carrying sufficient foodstuffs and other requisites for three months,

prospecting, as they proceeded. The Cobalt boom was at its height at the

time, and the fever-stricken prospectors, many of them amateurs, were

rambling over the country in all directions. To many of these greenhorns

the Montreal River proved a Waterloo. The stream swings along at a

terrifying pace, bristles with perils of the worst description, and can

only be navigated safely by an old hand. Yet many of the tenderfeet were

foolish enough to attempt to master its idiosyncrasies and dangers

without any previous boating experience whatever, with the inevitable

result—fatalities were numerous.

Lett pushed along in

one canoe, and hi» two companions managed the second boat. This was the

order of the day, but when the long, arduous portages had to be made,

the three boys joined hands, carting the baggage and boats over the

interruption in the water journey. They drove their way for fifty four

miles through swarms of prospectors, feverishly scratching the

hillsides, to Elk Lake, which then was being st arched energetically.

The trio, however, passed on, and once Elk Lake was left behind, they

found the number of mineral-searching rivals grow fewer and fewer in

number. This was not surprising, as the rock formation was extremely

discouraging, and appeared to grow worse, ,so far as mineral wealth was

concerned, the farther they pushed on.

The party reached the

foot of Nine-Mile Rapids, so called because the river rushes through a

narrow gorge at this point. It was late in the day, and a heavy lift of

one mile over a towering hill confronted them. They decided to put off

this stiff job till the morrow, so sneaking up in the eddy at the foot

of the Rapids, the canoes were run ashore, the dunnage was thrown out,

and camp was pitched. While the party were seated round the camp fire in

the gloaming, discussing the next morning’s task, they heard a peculiar

wail above the churning of the waters. It resembled the cry of a cat,

but the idea of seeing this animal in such a wild spot was so

extraordinary. that they dismissed its possibility from their minds,

attributing the wail to the rapids, because one Imagines one can hear

strange and fantastic sounds in the music of the waters. The howl

continued, and grew more nerve-racking. At last, one of the boys,

glancing round in the direction whence the sound came, spied through the

dusk a large black cat perched on the top of a cedar-tree, on the

opposite bank, and apparently calling for help. It was quite impossible

to rescue the animal, as the river could not be crossed unless they

dropped downstream a mile, and then there would have been very heavy

going over rough country to got at the cat’s eyrie. Suddenly, to the

astonishment of the party the cat gave a spring into the maddened

waters, and was lost to sight! It reappeared just as suddenly

downstream, swimming frantically, and as it was swung along in the

swirling waters, it grabbed the stub of a tree with a clutch of death,

pulled itself from the water, gave a bound, and landed on the same bank,

from which it had started. The party thought no more about the incident,

concluding that the cat would not reappear, after one such experience.

But to their amazement,

in the course of a few minutes, the cry broke out again, more

plaintively than ever, and there was the cat on the cedar-tree stamp.

Once more they saw it give a spring to land in the rapids. This time

pussy was taken well downstream, was lost to sight and the party thought

that the last had been seen of it. But just as they were curling up in

their sleeping-bags, the wail broke out for the third time. They were

too tired to keep awake any longer, and fell into the arms of Morpheus,

with the cat’s cry beating into their ears above the droning of the

rapids. For days after they thought they could hear the cat calling, and

wondering how such an animal happened to be so far from the haunts of

men, inquired of the fire-warden, whom they met a few daj s later. Then

the mystery was solved. The black cat belonged to a prospector, who had

lost his mascot some weeks before.

On this trip the party

accomplished an apparently impossible task—they built a cabin with

eleven nails. It may seem incredible, but it was an absolute fact, for

the simple reason that no more were available. When they struck a

blacksmith working at his forge, they gave him one of the nails, which

was a pretty big one, and he drew it out thin enough to make three

nails. As may be imagined, the nails were driven home with extreme care,

and in the right place every time. This particular blacksmith, Tom

Sharpe, was a handy man, and one who had been kicked by Fortune pretty

badly. He discovered the big Lawson Vein in Cobalt, which is a solid

streak of silver fully nine inches wide, and polished flush with the

country rock on each side. When Tommy made this find he was so new at

the business that he did not know whether he had struck iron or silver,

and the luck he struck brought him in only a miserable bagatelle of

£140!

The party traversed

country which was sheer wilderness, and which has still to await the

coming of the surveyor with hit, tranbit and level. Their luck appeared

to be dead out; so much so, in fact, that after they had crossed the

height of land between, Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes, they retraced

their steps, owing to the unpromising character of the rock, keeping to

the Montreal River until they gained Wapoose Creek. Here they called a

halt, two resting at the meeting of the waters, while Lett paddled up

the creek to make a reconnaissance for a suitable spot in which to camp.

After making one-and-a-half miles upstream, Lett was brought to a stop

by rapids, and then he decided to wait until his companions came up, as

they had promised to follow him. He kicked his heels idly about on the

bank for half an hour, and then, growing impatient, drew the bow of the

canoe ashore, and with his prospecting pick, decided to pass the time

ferreting round. There was a large talus heap in the vicinity, and he

started turning this over. He found the rock to be diabase, similar to

that found in the Cobalt silver area, and this was very encouraging. He

examined the broken mass carefully, and finally lighted on one piece

which bad evidently broken away from a vein many years before. It proved

to be caleite: the scent grew stronger. Indeed, it was the first

promising find the party had made during many score miles of search, and

this discovery proved that the country might possibly be very rich in

valuable mineralized veins. Lett was so elated with his success, that he

pitched a chunk of the rock into his canoe, and swung downstream to pick

up his companions, to report the result of his find. He found the two

boys slaving for dear life preparing a camping-ground, and having a

lively time. The mosquitoes had turned out in force to repel the white

man’s invasion, and they were about the most ferocious members of their

race that they had ever struck. Before they could obtain the slightest

respite from the vermin’s onslaughts, they had to don buckskin mittens,

to plaster then skin with fly “dope,” as the Halve against bites is

picturesquely termed, and to enclose their heads in miniature meat

safes. Even then they failed to hold their own against the swarms of

formidable insects, but had to abandon their camping-ground, and to

withdraw their forcer, to a flat rock of slate, which projected into the

river, and on which they raised their tent, weighting the ropes with

heavy stones, instead of securing them to pegs.

The calcite find was

discussed very eagerly that night after supper, and under the

circumstances it was decided to follow up these indications in the hope

of striking a rich vein. The next day they pushed towards the foot of

the Wapoose Creek Rapids, and embarked upon a systematic investigation

of the rock formation. Again Lett drew a lucky card, for after two or

three days’ diligent prospecting, he lighted upon a tiny piece of cobalt

bloom, which indicates the presence of smalltite, the ore of cobalt. The

“ strike ” was made, and the trio set to work staking their claim.

The three prospector?

have received the due reward for their temerity in venturing into an

unknown country, and their arduous tracking through mile after mile of

exasperating primeval country, for they hold no less than 410 acres,

containing ample water power and innumerable indications of a rich

deposit of silver, which has been proved in largo quantities by the men

engaged in performing the assessment work required by law. Lett and his

companions not only were among the first to penetrate the Gowganda.

country, but their exploration work was carried out to such distinct

advantage, that their results have become of value to the Government,

and the foundations of a second Cobalt have been built, ready to go

ahead directly the railway reaches it, and permits machinery to be

brought in.

Thus it Will be

realized that systematic search brings its fruits in due time. Yet the

prospector does not always reap the harvest of his hard toil. There was

Vital LeFort for instance. This French-Canadian from the East was among

the first to track gold in British Columbia. A rush ensued to “Vital

Creek,” as the hub of activity was called. Many made money out of that

strike, but not so the man responsible for the excitement. He failed to

rise to the occasion, being content to sit on his claim. When I met

Vital LeFort, he ferried me across the Nechaco River, within sight of

the Hudson Bay trading post at Fort Fraser. This was his only source of

income, the Government having placed Him in charge of the means of

crossing the waterway at this point, with the revenue from the traffic

as his means ox livelihood. Even this calling is in danger of

disappearing, because the iron horse is hurrying rapidly through this

country, and when it arrives, there will be little traffic to be ferried

across the river. |