|

The Royal Mail Service,

like time and tide, waits for no man, and will brook no interference

with its ordained movements. No matter whether the round is along city

pavements, across sweltering deserts, through cavernous forests, over

frozen snow bound wastes, or by miasmic swamps, if the fiat has gore

forth that letters are to be delivered to, and collected from, the spot

beyond, the mail service must be maintained at all hazards. He who

enlists in the service, and undertakes to get the bag of correspondence

through, must be prepared to face any contingency; to surmount any

obstacle. The postman must complete his round.

It is one of the

outstanding features of British colonization or settlement and

developing work, that those engaged in pioneering shall not be denied

the postal privileges of civilization. The delivery and collection may

be erratic from causes over which man has no possible control, but the

frontier town accepts the inevitable without a murmur. Directly a little

settlement springs up in the remote wilderness the threads of the postal

service of the country are rewoven, so as to bring the new arrival

within the meshes of the net by mean3 of which letters are swung to and

fro.

Within the purlieus of

the city the postman's round is humdrum, but in the “rural districts,”

as the wilds are euphemistically called in official parlance monotony

gives way to romance and adventure. The round may be one of 200 miles

from end to end; its completion out and home may mean three weeks’ hard

travelling, over a trail which is scarcely recognizable, by any type of

vehicle that may be available, from a raft to horse’s back, and when

transport fails them “Shank’s pony” becomes the only alternative. The

elements may conspire together to defeat the most carefully laid plains

of the authorities and the grim determination of the man on the round—

but he must get through. It may rain as if presaging a second Deluge:

the forest fire may smoke every trace of animal life out of the bush,

converting the country into a scorching inferno; the blizzard may rage

in frigid fury, sucking the life out of all that comes within its rimy

embrace, blotting out the trail beneath a white blanket several feet in

thickness; the rivers may swell and bar the path with a frenzied rush of

white bubbling froth— but the mails, must go on.

It comes as a shock to

the city dweller with the postal service running like a clockwork

machine to strike the conditions which prevail in the wilderness. A

shack, decrepit and tumbling, which would be passed in disdain because

appearance tends to show that it has long since come of age, compels

earnest attention, for there, over the rhomboid shaped doorway are the

magic letters “G. R. Post Office.” Along the trail a slouching figure is

seen mushing with mechanical tread. He is a sorry-looking piece of

humanity when espied in the distance, and with his bag slung over his

shoulder, gives the impression of being a hobo who has struck a rich

vein of bad luck. You give him a cold hail, and the figure answers back

just as monosyllabically and freezingly. As he approaches you are

prompted to hold him up for conversation, but the stranger presses on,

answering questions as he proceeds; and then, as he swings his arm round

you catch sight of the badge “Mailman.” If the country happens to be so

far advanced as to boast a crude frontier road, ever and anon you may

hear the jangle of bells, and a light buggy comes reeling along at a

breezy pace. As the driver lurches by he gives you a nod, but never the

offer of a lift. He has His Majesty's mails aboard, and the bag of

letters is of far greater importance than a hundred pounds or so of

human flesh. Or, perhaps, you have hit the stage coach, as the

tumbling-to-pieces aggregation of rough wood slung on four wheels

without the intermediary of springs, is called. The chances are that: it

is packed to creaking point, with baggage and passengers, but there is

only one bag aboard which occupies the mind of the driver. This is under

his dickey, and he sits on it tightly to make doubly sure of its safety,

because it is the property of the Postmaster-General.

I met one of these

frontier postmen one day on his lonely “rural” round. The trail led

through a swiftly running creek, not very deep, because it could be

forded without one getting wet higher than the thighs, but tricky

because the boulders forming its bed were always about. The postman had

forded this creek safely times without number, but on this particular

occasion he fouled a large, slippery boulder, and before he realized

what had happened, he bad measured his length in the water, while the

mail-bag went careering downstream. With great difficulty he recovered

his charge, and when I came across him, he was seated before a roaring

fire, which he had kindled, drying his precious letters one by one. Some

two or three days later he crawled into the camp where I was staying,

and as he tendered the misives apologetically, explained what had

happened. The boys laughed heartily as they tore their respective

letters open, and although some fearful ejaculations were muttered as

frantic endeavour unravelled the pages stuck together, there was not the

slightest complaint. They thought themselves mighty lucky to have got

their letters at all under the circumstances; a vivid contrast to the

habitual growler in the city, who is ready to send a sour pago complaint

to the authorities because a letter happens to be delayed half a day

through inadvertence. In the wilderness it is far better that a message

from home should be delivered in a semi-mashed-potato state than not at

all.

At times it is a mighty

hard struggle to get the mail through. We struck one waggon road, and

were held up completely by the devastation wrought by a bush fire. For

half a mile the highway was littered with the trunks of huge trees,

which had crashed to the ground because the flames had undermined their

roots. While we were pondering upon the situation, the mailman in his

buggy came up. lie was not perturbed. He looked at the healthy maze of

trees, and then at his axe. A few seconds’ reflection convinced him that

it would lake him days to clear his way through, so he backed his buggy

into the bush, detached his mount, pulled out the bag of mails, hitched

them on the back of his animal, and shouldering the reins, trudged into

the scrub, following an Indian trail. It was a wide detour, but it led

right round the burnt area for a distance of fifteen miles, to the next

station, which he completed on foot, arriving at his destination about

six hours late. That was all the inconverience the bush fire had caused.

He spent the night at the post, made his collection-performed once every

three weeks--shouldered his bag, and tramped back to the spot where the

buggy had been abandoned temporarily. Once more his horse was harnessed

up, and with a whittle and a “git up,” he started off on the homeward

jaunt, as if bush fires and burnt fall were the very last obstructions

encountered on his journey.

There are plenty of

openings for those who wish to serve His Majesty the King in the humble

role of postmen through the “rural” districts. Periodically

advertisements are issued, calling for men and tenders for the delivery

and collection of letters over a certain distance. The scale of pay

varies. In some cases it will run to £10 per month; in others a higher

rate of wages prevails. It all depends upon the country to be served and

the difficult nature of the task.

For instance, in New

British Columbia I found that the postman started off from Quesnel with

his vehicle bound for Fraser Lake, following the frontier road, and

completing from twenty to thirty miles a day, the night being spent at

the stations of the Yukon Telegraph. The Telegraph cabins serve as

post-offices where stamps may be purchased, letters posted, and parcels

handed in. On the other Land, the Skena River was the highway for postal

communication so far as Hazleton, whence the mails were sent so far

south as Bulkley Cabin, a distance of about 100 miles. For points

between Bulkley on the one, and Fraser Lake on the other side, the

postman had to make a big cross-country jaunt from Bella Coola, a small

cove on the Pacific coast, and consequently the Telegraph cabin at Burns

Lake, which is mid-way between Bulkley and Fraser Lake, was in an

isolated position, and the mails were infrequent—but sure. I posted a

letter home at Bums Lake, while making the North-West Passage by land,

and then pushed on towards the Skeera River. I arrived home about eight

weeks after I left this cabin, and the letter I had posted followed me a

week later—but it reached its destination safely and soundly.

The authorities make a

point that all people engaged in pushing back the veil of the unknown

shall be supplied with a mail service. Accordingly, the very uttermost

camps of those engaged in railway surveying and construction receive

letters as close to a regular schedule as is humanly possible. The

letters are sent forward by train to the railhead. Here they are picked

up by the post-master of the end-of-steel town, and by him handed over

to the postman. The latter starts off on his trudge from camp to camp,

strung out over a distance of 150 miles. The general day’s round is

about twenty miles from one resident engineer's camp to another. He will

breakfast about seven at one camp, start out, reach the next in time for

the midday meal, and pushing on, stop in the succeeding camp for supper.

He will put up for the night at this point, hitting the trail again

about seven the following morning. He is well tended, receives

first-class meals, and a good shake down for the night, these

requirements being supplied free of cost, so that his £10 or thereabouts

is clear, unencumbered pocket money. On the outward jaunt he drops

letters only, collecting correspondence on his return trip.

The scene on the latter

occasion at a camp where the postman is pausing for meals is a busy one.

Every member of the community will be found writing as for dear life, so

as to complete his letter in time, because the postman makes no delays.

He discusses his meal and packs his bag at once, because he knows just

how long it is going to take him to reach the next camp in time for the

evening meal.

I encountered one or

two experiences of this adherence to system, even in the bush. The

engineer at one camp had not completed a report which he was anxious to

mail to headquarters. The postman had started off at his stated hour,

but the engineer, to catch the mail, had paddled a horse and ridden full

tear after the walking mailman, had handed over his letter, and

returned, making a twenty-mile ride. In another case an Indian was

pressed into service. The postman had about four hours’ start. But the

Indian, springing on to his cayouse, as he calls his pony, had sped off

under the incentive of a 5-dollai bill, if he caught the mailman. At

every constructional camp the Indian jerked out the query: “Mailman

gone?” Receiving an acquiescent grunt, he asked: “How long!” The

information forthcoming, the Red rider dug his spurs into the flanks of

his steed, clattered forward over deadfall, and crashed through creeks

as if the going were as easy as galloping over a green sward. But he

caught the mailman in the middle of his supper, handed over the letter,

hastily swallowed a meal himself, and then, jumping astride his mount,

tore off into the waning day, to notify the fact that the letter was

safely mailed, and to pick up his hard earned 5-dollar bill.

The postman, as a rule,

under these conditions, follows the best route open to him. He is not

supplied with any conveyance, so has to walk from point to point

shedding or accumulating his load as he plods through cutting, over

embankment, across swamp, slipping and sliding among boulders, fording

creeks, and braving rushing rivers as best he can.

The mailman’s lot is

facilitated so far as the conditions will admit. If he is forced to

proceed afoot, his load comprises first-class mail only—that is,

letter-packets. Newspaper's, books, and parcels are sent along at

irregular intervals. If a freighting team happens to be going in the

direction of certain camps, and has room aboard for a consignment of

heavier mail-matter, it takes it, but no delivery is guaranteed. Postal

packets, apart from letters, are regarded more in the light of luxuries;

it is the letter which receives such unremitting care, and for the safe

conveyance of which much hardship and toil are suffered. Of course, when

a frontier road, with rivers and creeks spanned by bridges, are open,

then the wheeled vehicle which is pressed into service carries all kinds

and descriptions of mail matter, the contract between the individual and

the Government being drawn up to this end. Even then the undertaking

only holds good throughout the summer months, when wheeled-traffic is

possible. In the winter different arrangements prevail, book packets and

parcels being held up five months or so in some cases.

On the waterways, so

far as possible, the mail is handled by the shallow draft steamboats,

which proceed up and down, the passing vessels being hailed by the

mailman through the intermediary of a flag. Even boats which are not

scheduled to stop at certain points for passengers or freight will halt

momentarily to pick up the mail.

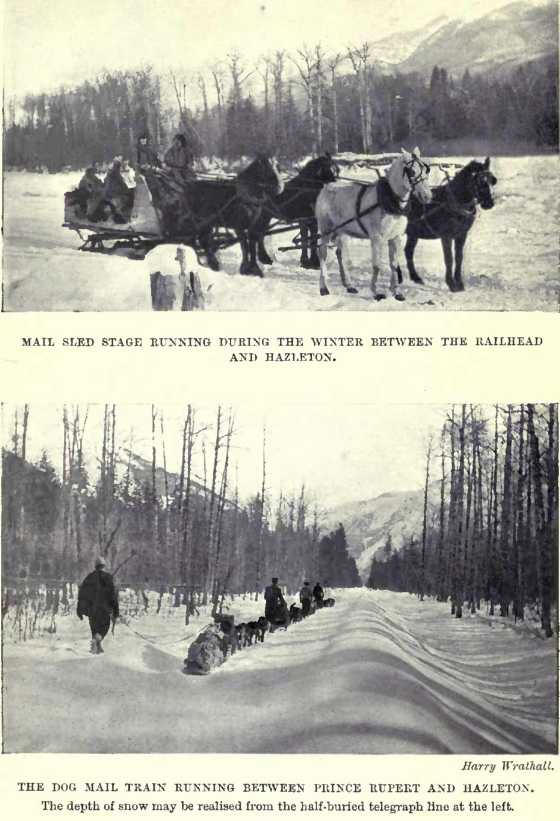

Winter demands the

reorganization of facilities and methods for handling the mail, and this

is the period when the task of the authorities is beset with innumerable

perils and dangers. The rivers being frozen almost into solid blocks of

ice, navigation is out of the question. Delivery on foot is equally

impracticable. On the frontier road it may be possible to maintain a

service with horse-drawn sleds, when all descriptions of postal packets

may be handled with ease, but otherwise there is only one possible means

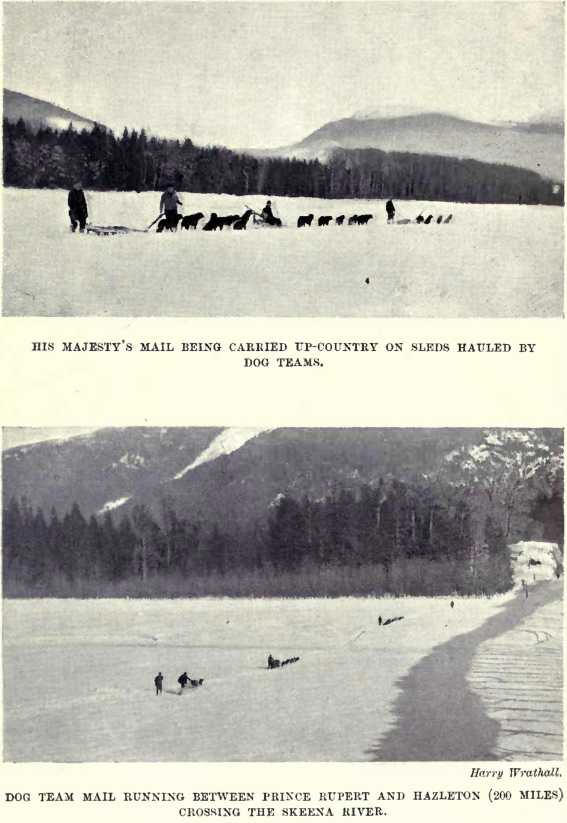

of keeping the service going—by dog trains.

The Government

concludes arrangements with private individuals who are in the

possession of well-equipped vehicles of this description, and the man is

left absolutely to his own devices to complete his undertaking. Rut it

is rough and exciting work. A train of huskies can handle a weight of

200 pounds, but this available weight has to be divided between the

mail-load and the requirements for the man upon his journev. As may be

supposed, nothing but letter packets are handled under these conditions.

While sometimes a single man will set out with his precious load, the

train more often comprises a party of three, each having a team and

train, and with the mail divided between the three sleds, while a fourth

man will go ahead on his snow-shoes to pick up the trail. This method is

preferable, because often the mailmen encounter obstructions or get into

such tight corners that extrication is only possible by combined

superhuman exertion, and would be quite beyond a mailman travelling

alone.

The dogs are powerful

brutes, lithe and active, and able to keep going, when the emergency

arises, upon the most slender fare. Their stamina is wonderful, equalled

possibly only by their ferocity, which occasionally finds an outlet when

the brutes rise in rebellion. Then lively times are witnessed. The

murderous whip is the only means whereby they can be made tractable once

more, but the process of subjugating their tempera is one of

considerable exertion on the part of the mailman. One of the boys who

ran one of these trains on the outskirts of Ontario for three successive

winters, concluded that he had the most unruly and vicious huskies that

ever were harnessed to a sled. When they got into their stride, they ate

up the miles one after the other in fine record-breaking form, but the

great trouble was to get them to start. Every morning there was a row.

First they started fighting among themselves, letting pandemonium loose

in the heart of the wilderness. The mailman’s usual procedure was to

jump among them with his whip, letting it out right and left

indiscriminately in a determined endeavour to separate the brutes. Ten

minutes exercise of this weapon generally brought about the desired

result. Then came the difficulty of harnessing them up. One and all were

sullen, snarling, and evil-looking. The mailman had to keep both his

eyes and ears open, with whip handy to let fly at the slightest sign of

attack. They watched him to and fro like a coyote stalking the trail,

and he recognized that it was only the fear of the whip which kept them

submissive. The safer practice was for one man to harness up and pack

the sleighs, while the other stood by vigilantly watching the animals

with whip upraised, ready to bring the steel-like thong down with enough

force to cut through a brute’s back-bone.

Another mailman, who

ran the mail by dog train in the Yukon country, related how every

morning there was a tussle between him and the dogs. He had a long pull

of about 300 miles with his train, and sometimes went accompanied and

sometimes alone. Under the latter conditions the brutes thought they had

the upper hand— at least, they fought desperately to gain it. When they

were called to be harnessed up, they point-black refused to stir a

muscle. Even the threat of the whip did not provoke a blink. Every dog

in the team had to be lashed and thrashed before he would submit to

harnessing, and then when the whole train was ready they had to be given

another liberal dose of whip-lash before they would move. When they got

going there was no holding them in, and in favourable weather he was

hard put to it to keep up with them. Those huskies’ interpretation of

the word “kindness” was a sound thrashing of five minutes’ duration, by

the end of which time both animals and man were somewhat distressed.

As may be supposed, the

mail, being consigned to such a tender vehicle as a dog sleigh, and

having to be carried under such adverse conditions, suffers severely

from the ordeal at times. When a dog train gets into its stride, and the

snow has packed hard, it makes a good, healthy pace; but the heavy

carpet of snow conceals dangers untold, and the sled is not built to

withstand too prolonged or heavy a game of battledore and shuttlecock.

It bounces and lurches from side to side, although the mailman tries

valiantly to keep it steady. If it strikes a tree stump smartly it

shoots oft like an arrow shot from a bow glancing off at the most

unexpected angle, often to pull up against another stump on the opposite

side of the narrow pathway. Now and again the sled will give a shoot

into the air, and come down with a healthy crash to hit a tree stump a

fair end-on smashing blow. When 200 pounds is moving at the velocity of

four or six miles an hour and hits an immovable mass, something happens,

and it is not the tree which suffers; then the animals have to be

hitched up while the sled is beirg repaired as best the conveniences at

hand will permit.

Occasionally, as a

result of a collision, the contents get scattered to the four winds. One

of the boys related an experience which befell him during the previous

winter. He had an average load aboard, and had a clear 100 miles run in

front of Mm. The snow was hard, giving a surface like an asphalt

roadway, and the train was making fine time. He calculated that he would

pull into the shack serving as the night camping-place in excellent

time, and be able to get a good rest, which had been denied him for some

nights previously, owing to the thick heavy weather which had rendered

the going slow and arduous. They were sailing along, and he was humming

merrily at the prospect, when suddenly there was a crash, a lurch, the

sleigh flew into the air like a rocket, he measured his length on the

snow, and ploughed along for about three yards on his head. He picked

himself up and found himself being wreathed in what he thought were the

biggest snowflakes he had ever seen in his life; the sleigh had cannoned

a hidden obstruction with healthy force, had leaped into the air, and In

so doing the mail bag had been ripped up by a murderous snag. What he

thought were snowflakes were the letters from the bag! They were

scattered all round him like leaves.

“Three hours that smash

cost me,” he growled, as he related the episode. He hitched up the dogs

and then went very carefully over the ground searching for letters.

Some were caught in the

scrub, others were impaled on snags, while others were blown twenty feet

or more from the point of the smash. Fortunately the weather held up,

and there was very little wind, otherwise, as he significantly muttered,

“I guess some of the stiffs would be still wondering where their letters

had gone astray.” In his own mind, however, he did not think that a

single missive was lost.

More unfortunate was

the result of another accident. The mailmen reached camp dead beat from

battling with a fierce blizzard for over ten hours. It had been

exhausting work getting the dog train along that day, and even the

animals bore signs of the fight with the elements. The men fed the dogs,

piled up a huge fire, prepared their supper, and before it was completed

they fell asleep. When they woke in the morning they sat, up, looked

round for the laden sleighs, and then rubbed their eyes. The vehicles

were nowhere to be seen! They could not have been stolen in the night,

since the dogs would have given the alarm. What had happened? They

jumped hastily to their feet and rushed to the place where the sleds had

been stacked. The truth was soon told. Being dead-tired they had not

noticed that the vehicles and their precious freight had been left

standing near the fire. The flames being fanned that way by the wind

first had scorched and then had consumed them. Not a letter was left,

only small heaps of ashes, some charred leather, and a few screws and

nails!

Another dog train mail

had a very narrow escape. The party were cutting across a frozen river.

The ice appeared safe enough, for there was not a smirch on the white

covering. The train was about halfway across when the dogs in the front

vehicle gave a loud, frenzied yelp and jumped madly forward; they were

up to their girths in water. The mailman on snowshoes let out with his

whip, and the whole safely cleared the hidden danger; but the following

sleighs did not fare so well. They crashed into the hole left by the

first vehicle, and the dogs were soon swimming madly for their lives, in

danger of being dragged down by the laden vehicles. The mailmen grabbed

the sleighs, and smartly whipping out their jack-knives cut the

mail-bags loose, throwing them clear of the hole, and hacked the traces

in twain to give the dogs a chance. One man slipped through the ice, but

shooting out his arms kept his head above water and was pulled out

shivering with the cold. Two sleighs were lost, but the dogs and mails

were saved. The party, in crossing the frozen river, had stumbled upon

an unseen crack in the ice, and but for the presence of mind of the

mailmen a nasty accident would have had to be chronicled. All they lost

was two sleds, a greater part of their outfit, and half of their

provisions. Regaining the bank they hastily improvised a sled and pushed

ahead. Fortunately they were only about thirty miles from their

destination when the accident occurred.

One of the hardest

stretches of country over which the mails have to be handled at present

in Canada is the winter pull from the inland terminus of the Yukon and

White Pass Railway to Dawson City. During the summer months the waterway

is the channel along which the Royal Mail flows to and fro, but in the

winter, when the Yukon River is gripped in ice, the mails have to be

sent overland. And over what a road! In the summer the mails could not

go that way even if there were no other available because pack animals

would sink to their girths in a slime more tenacious than glue; because

the road traverses wicked muskeg and tundra for practically the whole

distance between the two points. Subterranean springs innumerable, the

thawed snow, and the melting glaciers transform the whole ground into a

kind of soddened sponge, where horses cannot get a foothold, and where

wheels slip out of sight.

When the ground is

frozen hard and is covered with snow, the surface offered for the sleigh

is excellent, but now and again everything is thrown sixes and sevens by

a warm spell which catches the passing traffic at a heavy disadvantage.

Also the grades are fierce, ranging from 1 in 5 to 1 in 10. So heavy is

the travelling that the sleighs carrying the mails have to be drawn by

six horses, and these have to be changed every twenty-two miles, three

relays being made in the course of a single day’s travelling lasting

about twelve hours. The road is well defined so far as this task is

practicable in such a country, though at times it is wiped out of

existence by playful antics of Nature, and it costs the Government a

neat little sum every year to keep it open. At intervals of every twenty

miles there are convenient shacks— memories of the “blood-freezing days

of ’96” when the North-West Mounted Police were keeping law and order,

so far as Canada was concerned, in the Klondyke.

This stretch of mail

road is considered to be about the worst in the whole Dominion.

Certainly it would be difficult to find one more arduous and

exasperating. When first opened, dog trains sufficed to meet the

situation, but the traffic during the winter between the two posts

developed to such a degree that to-day only horses can cope with it. One

is able to mail a letter from London to the Klondyke for a penny, but

every missive must be carried at a dead loss between Whitehorse and

Dawson, owing to the demands upon twenty-four horses, and with hay at

£20 per ton!

The mailman’s life is

decidedly varied and exciting, but apparently there appears to be no

difficulty in getting an adequate supply of right men for the work. It

certainly constitutes a means of earning a respectable living in Canada,

and one which has many decided attractions for men of the true British

temperament. |