|

The agricultural

labourer and small farmer who, dismayed with the slender prospects

confronting him in these islands, decides to try his luck in Britain

across the Atlantic, is sorely perplexed as to where he shall settle in

that vast country, and how he shall set about the land. He is assailed

with the advice "to place his services at the disposal of a Canadian

farmer to learn the business; to become familiar with the Canadian ways

and means of doing things.” In other words, he is urged to teach the

Westerner the science of the soil in return for a starvation wage.

This is about the most

doubtful advice that the new arrival could follow. The average Western

farmer is an overrated personality. He knows nothing about even the

rudiments of his craft; fertilization is an art beyond his knowledge;

while how to obtain the maximum yield from the soil without exhausting

it is a matter about which he is quite in the dark. He boasts about his

bounteous crops, ignoring the circumstance that he himself does not stir

a hand to assist in their propagation. After he has ploughed up the land

with his much-lauded team or petrol-driven plough, and has seeded it to

flax, wheat, oats, and so on, he leaves it to its own devices, to bring

forth what it can. If he wishes to increase his aggregate production he

does not attempt to study the soil to consummate this end, but merely

ropes in a further area of virgin prairie for cultivation.

The Canadian is the

absolute antithesis of the competent fanner—indolent- ignorant, and

conceited to boot. The results he achieves are not due to his own

exertions, but to a kindly pity on the part of Nature, who produces the

maximum in return for the minimum of work on the part of the man in

possession.

Agricultural economists

have realized this attitude of “being proud in his own. conceit” which

is manifested by the Western farmer. The same story is being told in the

United States, so it is not peculiar to the land stretching to the

Arctic circle. These authorities see the day when Nature will tire of

helping the ignorant and incompetent, and will give him a severe kick in

the back to bring him to his senses. It has happened in the United

States, and it will befall Canada. The grain-growing superiority of the

United States has passed to Canada. The last-named country to-day is in

danger of being relegated to a low position by Australia, the Argentine,

Russia, and Siberia, where farming as an art is practised. The Canadian

is mighty proud when quoting wheat statistics, end has been afflicted as

a result of boasting and advertisement with an acute attack of swelled

head. It comes as a nasty shock to his pride to learn that France, with

an area about one-fifteenth that of Canada, and with a population six

times as great, can grow within its own borders, not only more grain

than Canada at present produces, but sufficient to support its own

people; and that Denmark, one of the smallest countries in Europe, as an

exporter of dairying produce, has not a rival throughout the world.

From my own

observations of the wasteful and incompetent methods I would urge the

British emigrant not to follow in the Western Canadian’s footsteps so

far as this Handicraft is concerned, but to resume in his new, just what

ho practised in his old, home. If the Britisher wishes to investigate

Canadian farming as it should be practised, then let him amble through

the maritime provinces, where may be found a liberal commingling of the

best and old-time British and French blood, with all the agricultural

instincts developed to the finest degree, where the practice and produce

is comparable with that of the most important agricultural countries of

Europe.

It is only necessary to

cite one instance of the incompetence of the Western farmer—the “mammoth

grain-grower,” as he is apt to call himself. I was visiting a prairie

homestead, and with that true Canadian hospitality I was invited to stay

to supper—high tea or dinner it would be called in Britain, according to

the social status of the host. There was only one fresh article of diet

on the table! The milk was tinned; the butter came from Nova Scotia via

the jacking building, the vegetables and meats were examples of the

canner’s art; the preserves hailed from California, in tins, or were

preps red in the purlieus of Battersea and Soho. The only local

production was the bread! I questioned the farmer as to the reason for

this state of affairs. He replied that he would see Canada to perdition

before he would raise a hand to cultivate vegetables and fruit, or keep

a mixed farm! When the wheat wan in, he was off, and that was an end to

manual exertion so far as he was concerned. In other words, his yearly

life was four months on the farm watching other people work, and eight

months down south having a roaring time.

The Britisher, in

common with the agriculturist from Northern, Central, and Southern

Europe, has tired of serving such masters as these for £2 or £3 per

month, with every thing found for four months, and being left to his own

devices to ward off starvation for the remainder of the year. Any

newly-arriving back-to-the-lander who knows his business prefers to

settle upon a small tract of land to work out his own destiny. Hard

work, knowledge, and thrift, always bring their own reward, and in

Canada the prizes come home to roost very quickly.

Where to settle is a

puzzle which is not to be solved easily and off handedly, and the only

reason for working with a Canadian farmer in the West, so far as I can

see, is to keep things going while marking time, and making up the mind

definitely whether Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, or British Columbia,

or the Maritime provinces shall be the future home. Farming-land of the

most excellent description is still to be obtained fairly cheaply down

Nova Scotia way, and in New Brunswick, Southern Quebec, and Southern

Ontario, developed farms, the owners of which are anxious to get farther

West, may be picked up easily by the man with a small capital. The

British farmer would do well to reflect deeply before he ventures far

West, as in the Maritime provinces there is greater settlement, and the

markets are in closer and quicker communication, while when the moment

comes, and the latest arrival has concluded that he would prefer the

Great West, it is not difficult to dispose of one’s holding at a

remunerative figure.

The great difference

between Eastern and Western Canada is that, while the loner thinks and

transacts in cents, the latter considers the dollar to be the basis for

business. This is attributable to the fact that money is made much more

easily and quickly between the Great Lakes and the Pacific, than between

the Atlantic seaboard and the Lakes. The ninety-fifth meridian west of

Greenwich is practically the dividing between cents and dollars. To the

west rolls the undulating prairie, where one can enter into possession

upon the virgin sod in the spring, and receive the worth of a crop in

the last year; to the east extends the great ocean of forest, where

clearing is slavery, and where one is lucky if one is able to clear and

bring 160 acres under remunerative cultivation in the course of a

generation.

The difference between

Eastern and Western Canada was put very neatly to me by an old farmer

who had tried his luck in both. “On one side I worked not for myself but

for my family, who would fellow me; on the other I started away at once,

and have the prospect of being able to enjoy a little of the evening of

life.”

In the settled parts of

the Eastern states, where development is practically complete, the new

arrival has got to pay just as much for his lard as he would in Britain,

and his taxes are not much easier. The only things which save him are

the increase of markets extending beyond the limits of the country, and

the climate. All phases of farming become remunerative, whether it be

stock-raising, dairying, market-gardening, or fruit growing. If the

British farmer continues in the rut which he practised at home he will

spread his risks over a wide area, and all branches of the craft will be

followed, so that, for instance, if his fruit fails, he will have the

other sheet-anchors upon which to depend. In the Middle West the vogue

is to place all the eggs in one basket, to concentrate all hopes and

failures upon one product. If the fates are kind, the balance at the

bank runs up like a thermometer dipped in boiling water; if a drought or

other untimely visitation makes a stride your way, then you must

consider the advisability of “hitting the hike,” otherwise, moving

elsewhere in search of a job, very thoughtfully.

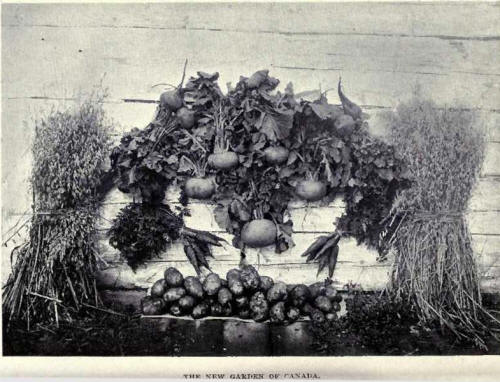

Yet the Middle West

to-day offers the greatest possibilities for mixed, or, to quote the

vernacular, truck-farming. Prosperous towns are going ahead with

astonishing rapidity, and the swelling populations show an ever

increasing and steady demand for the products of the market gardens in

infinite variety. Eggs, poultry, butter, cream, potatoes, cabbages,

lettuces, fresh meat, and flowers are in urgent request at such places

as Winnipeg, Regina, Brandon, Calgary, Edmonton, and so on. As a matter

of fact, the demand still completely, and for many years to come, will

overwhelm the supply. There are more tinned comestibles sold in these

centres to-day than similar edibles in their fresh condition, merely

because the farmers within a stone’s-throw of these markets will cling

to the fallacy that “Wheat is king.”

On the treeless prairie

the period between occupation and production is very brief. The new

arrival need not kick his heels about, nor toil from morning to night

for many mouths, before the sweat of his brow meets with a fitting

recompense. If the practice which 1 saw adopted by a hunting American

family is followed, then this period is reduced to the absolute minimum.

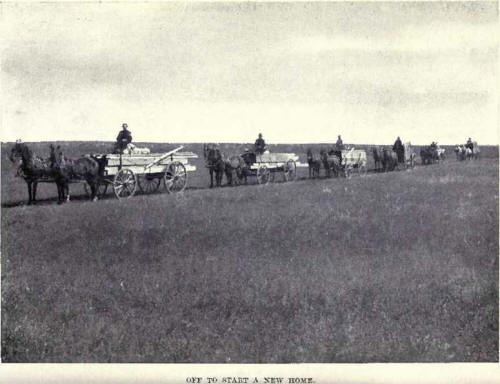

This farmer had sold

out his holdings down in Dakota, and had purchased a new farm of several

hundred acres in Alberta—incidentally making a few thousand pounds over

the transaction, owing to the farm down South fetching about £8 an acre,

while the new one to the North had been purchased for less than £3 per

acre, but had declined to dispose of his agricultural implements, which

comprised a comprehensive power-plant. He saw the tools stowed away on

the railway cars down in Dakota, and arranged that while he and his

three sons of mature age should proceed Albeitawards, his wife, and the

children of younger age, should stay with friends in the United States.

The farmer and sons

started off, and reaching their new home sized up the proposition,

settling the situation for the homestead, and other details. They

received intimation from the railway company that their implemerits bad

reached the station nearest the farm, and the cars were waiting in the

siding. Ere the sun had got above the eastern horizon the party were en

route for the railway-station, the trucks were unloaded, and in a short

time the little party was jaunting homewards. Directly the farm was

gained, all but one, the youngest son, set to work on the land. The

ploughs were hitched to the tractor and the first furrow was started.

The youngest son meanwhile saw to the preparation of the morning meal,

and running up the A-tent, which was to serve as a home until there was

spare time to commence erecting the homestead. By the time the first day

drew to a close a respectably-sized patch of the prairie had been

converted from the primeval green grass to gashes of brown, showing

where the sod had been turned. The family kept at it day after day until

the whole of the available area had been ploughed and seeded to flax.

This accomplished, the party took the home in hand. By the autumn they

told me they expected to have everything completed and in apple-pie

order in readiness for the mother and the younger children. In this

instance, therefore, less than six months were to see several hundred

acres of flat land wrested from virginity, turned to bearing, and a

healthy family settled in a substantial house.

The emigrant who is

likely to succeed to the greatest advantage in the West is he who is

blessed with a large and growing family. In Great Britain children are

regarded as mill-stones around the necks of the parents; in the far West

they are unalloyed assets. One and all represent so much available

labour, and the farmer who has a family of healthy, sturdy sons and

daughters is in a state of independence so far as labour is concerned.

Naturally the children toil hard and long because they realise that

every ounce of exertion they put into the father’s farm is improving the

value of their ultimate inheritance; hence they work not for the present

but for the future.

The man with a family

will come to recognize the benefit of his offspring, if he is possessed

of no, or very little, capital, and acquires a plot of Canadian freehold

through the homestead or pre-emption law. This is the cheapest method

whereby a new arrival may develop into a prosperous farmer. Certainly it

possesses many drawbacks, which in several instances demand revision. At

least five years of heavy gruelling have to be faced in order to receive

the deeds entitling the homesteader to the land, and if fortune is not

kind it is a terrible uphill struggle. But the man with no capital,

although possessed of plenty of brains, brawn, and muscle, has a tight

fit for a time in any country, and the difficulties in Canada are not

much more formidable than those prevailing under similar conditions in

other lands, although at first sight they appear to be. At the same

time, the homesteading law is full of abuses and anomalies, although its

conditions appear to be so simple to fulfil. There is no doubt but that

a very large number of new arrivals who settle upon the land by virtue

of the homestead law become disillusioned and dissatisfied with their

lot within a very short time. Any man who enters into occupation of

Canadian farms upon this principle, who has notched the thirty-fifth

milestone in his life, must become reconciled to the fact that he is not

labouring for himself and his own comfort, but for the next generation.

In other words, he will have the grind and his children will have the

dollars.

This feature is

particularly pronounced in the timbered parts of the Dominion, such as

Northern Ontario and British Columbia, where homesteading or pre-emption

is possible. There clearing is back and heart-breaking work, and the

homesteader is to be pitied, because he is unable to ease up in his

labour owing to lack of capital. To enter into occupation of a

railed-off piece of land half a mile square, where the trees are jammed

so tightly together as to have a stiff struggle for existence, is about

as dismal an outlook as one can conceive. It is little wonder that the

average homesteader, new to the country, when he surveys this aspect, is

smitten with a violent attack of home-sickness, and pauses to think

whether it would not have been better to have stayed at home, despite

the many fetters which shackled him there, than to tackle the Devil he

does not know in the wilds.

The homesteader will be

wise indeed if he steers wide of such forbidding country, where a

hand-to-mouth existence, hard knocks, and exasperating kicks from

fortune are certain to be his lot for many years. Getting in on the

ground-floor is a wise stroke of enterprise when one is familiar with

the conditions; but the raw recruit is apt to have his buoyant

enthusiasm knocked out of him when attempting to follow in the expert’s

tracks in this bid for fortune. He had far better cling to the highways

and byways of civilization, where the isolation is not so acute, and

where the loneliness does not precipitate madness. Britain is so densely

populated that one does not experience any feelings of being cut off

from one’s fellow creatures; but when one is dumped into the wilds with

the next door neighbour possibly twenty or more miles away, a railway

twice that distance, and where a newspaper is a luxury, the outlook is

vastly different. Nor must one overlook the fact that the Dominion, in

common with all such Continental countries in a similar latitude, supers

from the extremes of the two opposite seasons of the year. The country

is in its best garb of attractiveness and magnetization in the spring,

when the new arrival strikes it, but when the land is gripped in an

embrace stronger than steel for six months of the year, a vastly

different picture is presented, and which the immigrant does not realize

before he leaves his Homeland.

Of course, one can

pitch into corners of the vast Dominion where the tortures of winter are

mitigated by friendly natural influences. Whereas Northern Ontario, from

its exposure to the north, receives the full brunt of the Arctic cold,

the interior of British Columbia, on the other hand, owing to the

Rockies forming a formidable barrier on the eastern border, thereby

breaking up the cold blasts from the Polar regions, and the warm wind

blowing off the Pacific, finding its way through the rifts in the coast

range, render the inland plateau much more tenable during winter;

indeed, during the average winter it is possible to turn stock out of

doors. The snowfall, on the whole, is not particularly heavy, and

although the mercury in the thermometer at times is smitten with a

desire to sink almost out of sight, such spells are of comparatively

brief duration.

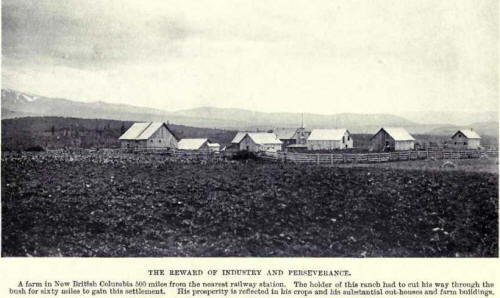

Central British

Columbia, when opened up by the railway, will become the most attractive

tract of the Dominion to the British settler—-a vast country where he

will be able to demonstrate his diversified and capable agricultural

instincts to the full, with every advantage in his favour. Clearing here

for the most part is not a soul-killing undertaking. In years gone by a

terrific forest fire evidently swept the whole plateau, levelling the

heavy timber growth to the ground to rot and to pile up a thick carpet

of nutritive decayed vegetable matter. From the ashes of these destroyed

timber giants has sprung a younger growth of cottonwood. True, it is

very dense, but it may be cleared very readily by fire. If the flames

are driven through one year, at such a time as not to burn up the thick

piling of moss and decayed leaves upon the top soil of silt, no as to

scorch the life from the scrub and then left for the greater part of

twelve months, by the lime a second fire is driven through the mass the

dead dried wood will be consumed like shavings, and the surface of the

ground, with its plant -nourishing wealth, will escape unscathed. The

stumps can be removed readily by the aid of a team of horses and a

puller, which will yank them out just as rapidly one after the other as

the hook can be hitched round them. The plough will find the soil easy

to work, and when the decayed vegetable and moss on top are turned in.

will be found capable of yielding any produce required in prolific

quantities.

Nor is the undergrowth

very regular in its extent. Scattered here and there freely among the

dense brush are small open patches—little prairies—where the settler can

establish himself comfortably and cultivate a small tract of ground

sufficiently to keep him going until the rest of his holding is cleared.

In fact, he should clear his land by instalments, extending his arable

patch year by year by driving the surrounding wall of trees farther and

farther back with the flames.

This plateau, nestling

between the Rockies and the Cascades on the one hand, and reaching fro

in peak bound Yukon to the Fraser River on the other, will enable the

British farmer to flourish in excel sin. The country is too undulating

to permit the much-vaunted Canadian or American prairie farmer to come

in with his mechanical outfit. He cannot get a long enough straight

level drive to bring these implements to work with remunerative

advantage. New British Columbia will never be overrun by the curse of

wheat, but rather will be to the western coast, and its many cities and

industrial lives, what Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are to the Atlantic

seaboard; where the farmer will turn his attention to the production of

a little of everything, from potatoes to eggs, grain to pigs, turnips to

dairying, and from cabbages to fruit and flowers.

The greater part of

this country has been reserved for pre emption, so that the man without

capital is given a sporting chance in the race for fortune,

Unfortunately, the British Columbia Government displayed tardy interest

in the welfare of this individual, who, in reality, constitutes the

backbone of every country, but let the land-grabbers and the speculators

run riot over the land, looting the cream of the country, and they are

now holding up the man who wants to work upon the soil. Land which these

worthies bought for a paltry 4s. or 10s. per acre—much of it for less—is

being held up for sale at £12 and £20 per acre, and as yet there is no

railway, and no markets for the farmer! If such outrageous prices

prevail under such conditions, what prices will be demanded when the

arteries of communication and the centres of consumption become

established?

The Dominion Government

pursued a more intelligent and far sighted policy when it threw the

Great North-West open for settlement upon its acquisition from the

Hudson Bay Company. The cream of the land was taken over for the settler

without means by the establishment of the Homestead Law. When the

Canadian Pacific Railway was driven through British Columbia, the

Dominion Government reserved all the lands in the province within twenty

miles of the line on either side, this being known as the “Railway

Belt.” Similarly, the Dominion Government railed off 3,500,000 acres of

land in the Peace Fiver country, lying between the 120th and 122nd

meridians, practically keeping the speculator out of business for twenty

miles on either side of the river. The benefit of this astute move is

being reaped by the settler of to-day, now that the Peace River country

is attracting such largo numbers of farmers; indeed, the facility with

which magnificently fertile land in that country can be obtained despite

the fact that the nearest railway line is some 300 miles away, is

responsible for the migration of the best of the farming element from

the more southern parts of the country. In the course of a few years a

little kingdom, entirely self supporting, will be found to be well

established and flourishing without the general handmaids of commerce,

along the banks, of this mighty river within the limits of the

Government reserve.

A practice which is

growing in the Dominion, and which possesses many attractive features,

is the letting of farms which have been acquired under the Homestead

Law. The settler complies with the requisition of this legislative

enactment by improving his property, and in due course secures

unfettered title to his property. The farm is then leased as a going

concern at a remunerative figure, the class of farmer taking avail of

this method being one of small capital, who does not wish to sink his

all in a farm immediately upon arrival, and who yet has no intention of

hiring his labour merely to another farmer. By taking a farm upon a

short tenancy, he is able to become familiarized with the conditions of

Canadian farming. There is no need to touch the capital, and yet it can

be increased from the available balance upon the tenanted farm after

defraying all outgoings, such as rent, as well as living expenses. The

method suits the original settler, as it affords him an opportunity to

get away from the spot to which he has been glued for six years, while

his property is being maintained meanwhile, and also bringing in a

certain income. Many farms have changed hands on this system, the tenant

after a short while concluding that the property which he is working is

lucrative, and accordingly he completes the purchase, tentative terms to

this end being drawn up as a rule at the time the tenancy is taken over.

The system possesses many recommendatory features, because the tenant

fanner !s not compelled to retain possession of the land beyond a

certain period, should he conclude that it does not meet his

requirements. Moreover, when he completes the purchase, he is not

necessarily called upon to invest the whole of his capital therein; but,

owing to the land being improved and developed, is able to negotiate a

mortgage with one of the banks on the property with which to liquidate a

substantial proportion of the purchase price.

During the past twelve

years or so homesteading has been going ahead by leaps and bounds, and

at the present day many settlers who have become freely entitled to

their holding are negotiating its disposal by this system. It offers the

man with small capital an excellent opportunity to become established as

a farmer with the minimum of expense, and without a long wait between

occupation and productiveness, which must necessarily ensue under the

Homestead Law. At the same time, he does not sink his little all in a

speculation which subsequently he may regret. The short tenancy gives

adequate time to turn round and to find out whether one can settle down

into a promising proposition. It is just the same as taking over a house

in England with the option to purchase. |