|

Winter is dreaded by

the agricultural labourer struggling hard throughout the greater part of

the twenty-four hours for £3 or £l a month, because then, on the prairie

particularly, unemployment becomes bitterly acute. The majority of the

farmers, both native and those who have trekked across the border from

the United States, close their farms after the harvest is garnered. With

the golden coin, or rather sheafs of crisp notes which have been

exchanged for the grains of corn, they hie off to the Sunny South, where

the rimy handshake of King Winter is unknown, to while away the months

in idleness and ease, until the spring arrives to enable them to

reappear upon their Canadian property.

When the wealthy farmer

goes o£l on pleasure bent, the farm-hand his a mighty poor lookout. He

is left to wear the soles from his shoes looking for work. Little wonder

that grain-growing is not regarded altogether as a blessing, and any

agricultural labourer who turns his feet westwards in the search for

work would do well to ignore the huge wheat fields, and to throw in his

lot upon farms where mixed farming is practised. There he is certain to

find employment the whole year round as the stock must be tended.

Still, if he is forced

to tramp, he need not waste very much shoe-leather in seeking for a job,

provided he is robust, active; and energetic. In the winter, when nearly

every other outdoor occupation is driven into a condition of

hibernation, the lumber-camp gets busy. The trees are ripe for felling

and conversion into the thousand and one requirements of commerce.

Logging is to the Canadian winter what cereal-raising is to the Canadian

summer—the staple industry, the life-blood of existence. If there were

no logging industry to keep the drifting shoals of unskilled labour

above water-level, the much-vaunted grain wealth of the great West would

become hypothetical, and an academic subject of discussion. Logging

flourishes actively from the wintry, ice-girt shores of the Atlantic to

the warm chinook-swept coasts of the Pacific, and from end to end the

life is much the same—rough, ready, and to the point.

Down Quebec way the

French Canadian, so picturesquely described in the poems of Professor

Drummond, holds undisputed sway. He is an uncouth individual, though

hospitable, in all conscience, but his boots are shod with vicious

spikes, with which he is ever ready to try conclusions against the soft

flesh of another’s face when provoked to hostility, and he requires but

very little rousing. He is an adept at la savate, and fisticuffs against

murderous spikes embedded in half an inch of leather, carried at the

free end of a muscular log as flexible and as strong as a steel spring,

are unequal odds. In the Middle West the lumber-man of experience is

generally a burly bully, and a sorry specimen of his genus at that,

capable of being brought rudely to his senses by a stiff upper-cut from

the tenderfoot’s fists. In the Far West he is a more tractable

individual, even though he does regard the revolver as an efficient

instrument of argument at times. Lawlessness, however, has been

suppressed almost entirely through the unremitting vigilance and energy

of the authorities.

The lumber-man is

probably the roughest and most uncouth specimen of humanity gracing this

earth. He is taciturn to the degree of moroseness. His life and labour

tend to foster these characteristics. Buried in the snow -bound

wilderness, swinging an axe from morning to night, throwing trunks of

trees about as if they were matches, and fighting the ever-dropping

thermometer, is not kid-glove work. It saps every trace of politeness

from the most cultured frame, giving birth to a new and strange code of

etiquette, which the wilds alone know and recognize.

Lumbering and logging

are the two most despised occupations in the whole of the Dominion. Why

1 No one can say, except that it is manual effort in its most emphasized

form. True, an unsavoury reputation has always lingered about the

logging camp, and this has filtered far and wide, so that the livelihood

is 1 thought within the limits of opprobrium. Yet swinging an axe from

snowy mom to freezing eve, bringing down giants of the forests at £8 a

month, is not to be declined when the stomach is faced with emptiness.

With food of the most strengthening qualities, although limited in

variety, building up bone and sinew, this wintry livelihood is not to be

despised. The average farm-hand, when thrown upon his own resources at

the end of the harvest, is wise if he turns his footsteps towards the

lumber camp. He will earn the same wage during the cold half of the year

as he can command during the moiety when the heat is intense, and the

timber is preferable to starvation. Maybe he will enter a firm which

considers the contract system preferable, and then he will earn just as

much as his muscle will feel disposed to bring him: the more he can do,

the more he will earn.

In the lumber-camp

physical strength and endurance are at a premium, and a goodly stock of

these attributes is certain to spell financial satisfaction by the time

the snow commences to melt. True, the knocks are hard and frequent, but

they only serve to strengthen the constitution and harden the spirit

more and more. The tenderfoot who strikes a lumber- camp in the

anticipation of discovering feather-bed conditions will be disillusioned

very speedily, for he will pitch into a strange world and be buffeted

considerably. But with an equable temper, accommodating manners, and a

bon esprit, he will score, for he will learn to laugh at the roughness

of his companions, and, with the display of a little diplomacy and

resource, will inevitably develop into a favourite among favourites.

There was one young

English fellow whom I can recall. He tumbled into Canada, as so many

have done before him, and will continue to arrive, until “House full” is

signalled far and wide. His pocket was as empty as his stomach. Looking

for work, his feet drew' him to the lumber-camp, where he settled down

to a dreary round of toil. His national obstinacy soon brought him to

loggerheads with his French-Canadian colleagues. Words led to blows, and

one burly wielder of the axe let out with his steel-armoured foot and

the energy latent in the elastic muscles of the giant legs. The kick in

the stomach punched the wind out of the English boy as easily as an

air-balloon collapses under a pin-prick, and the jar of the steel spikes

against his face just as quickly brought it back again. Instinctively he

let out with his left, which pulled up against the hardened jawbone of

his antagonist. Five split knuckles bore testimony to the impact, and a

swift following of the right, with a similar result, brought about the

outstretching of six foot of French-Canadian on Mother Earth. The

discomfited lumber-jack pulled himself to a sitting posture, more in

wonder than in rage, and when he regained his feet he v, as knocked down

again just as unceremoniously. Three times he bumped his head on the

ground, and then, pulling himself to his feet, he buried the young

Britisher’s hand in the five ramrod digits forming the French-Canadian’s

human vice, and shook his opponent’s arm as vigorously as if it were an

axe-handle. Ever after those two were fast friends. They felled trees

together, piled up sleds in company, and accumulated dollar-bills in

concert. The native had been at the game since his earliest days, and

what he could not teach his new pupil about logging -was not worth

knowing. He imparted his knowledge to his new friend with the utmost

frankness, and when the latter, by sheer force of merit, w as shifted a

few rungs up the ladder of success, ho took care that his quondam

antagonist was not forgotten. It must not be inferred from this that an

accomplished knowledge of the noble art is a certain lever to success,

but the factory is narrated for the mere purpose of showing that it is

adaptability to circumstances which is the governing factor in the

lumber camp.

It must not be thought

that the lumber-camp is a hotbed of individualism run riot. It is a

little world where the survival of the fittest is carried to its

bitterest conclusion. Yet at the same time the experience is one which

has often been the means of building up the strength, vim, and

self-reliance of one who has run to seed.

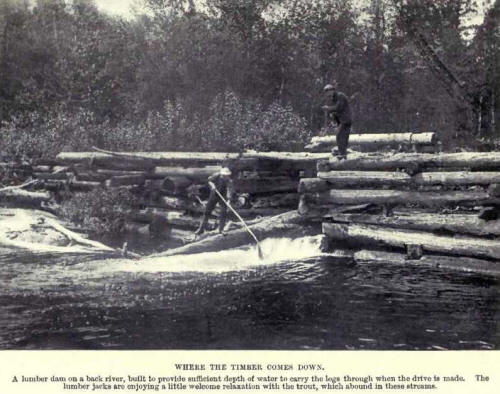

While the work of the

lumber-jack may bo described as uneventful, and to a certain measure

unskilled, this is only true so far as timber-felling is concerned. When

it comes to despatching the logs down the river, the difficulties of the

task commence in real earnest, and no little art is demanded to

circumvent the many and peculiar pitfalls, that lurk on every hand. At

places the stream is so shallow that there is insufficient water to

float the logs. To overcome this drawback the lumber man turns engineer.

He builds a dam, the opening in which is fitted with a stop-block. be

that the height of the water in the lake formed, by the timber barrage

may be regulated according to requirements. The log-lift is a very

primitive arrangement, and is handled by two men with levers. These fit

into holes in the log. and the men roll alternativly, a chain being

fastened inside the 1 tearing at either end, hooks being on the end of

the chains, which catch on iron pins halfway down in a mortise in the

stop-log. When a timber-drive has to be made, all the stop logs are

lifted, allowing the water to rush through the opening, bearing on its

bosom a jumble of timber. In this way the shallow' stream is given

sufficient water to bear the timber down.

Thrilling, exciting

stories without end may be related of the adventures encountered in

driving the timber down. More than one man. although expert at his work

has been nonplussed for a moment, to be thrown adrift into the raging

waters to dodge the ugly ends of the swirling logs; and more than one

has been brained in the process, to sink beneath the foam to rise no

more. Broken limbs and fractures at least are the positive rewards for

carelessness and it is not surprising, therefore, that the men keep

these penalties in view.

While logging may be

considered the bottom rung of the timber industry, if a man sticks to it

and displays any acumen he can ascend to bigger things just as easily as

smoke will rise upward. His acquaintance with the various trees in the

felling operations familiarizes him with the different woods, so that he

is able to tell at a glance the dimensions, texture, and species of a

tree. The mastery of these details leads to him being able to size up a

standing forest as to its quality of timber, probable yield, and

character, as easily as a stock-raiser can guess the weight of a hog. In

a word, he becomes able to convert so many square miles of standing

timber into its equivalent of pounds, shillings, and pence in the form

of lumber: he is fitted to become a limber-cruiser.

Timber-cruising is the

highest rung of the lumbering industry. It means that the expert must be

a bushranger, but that matters little so long as the end is justified.

The timber-cruiser’s life is without a parallel, unless one places him

in comparison with the prospector. The latter turns over the rocky

ground for monetary value in mineral; the former casts his eyes over the

sea of swaying green to estimate how much it is worth as boards, joists,

and other commercial forms of wood.

The timber-cruiser’s

life, taken on the whole, is full of adventure and thrills. He sallies

off into the heart of a new country, seeking for fresh forests which may

be depleted to satiate the rapacious hunger of the saws in the

lumber-mills, inspects the standing trees, reports upon their soundness,

suitability for certain purposes, character of the wood, stakes out the

claims, and sets forth how such wealth may be felled and brought down to

the sawmills with the minimum of expense.

I was ploughing my way

through a lonely corner of Western Ontario when one evening there was a

“halloo,” and a violent smashing through the scrub. Looking up, I

descried a gaunt, unkempt figure, rifle in hand, his clothes torn to

tatters, and a matted growth of tangled hair straggling over his face.

Across his back was thrown a blanket, which had suffered severely from

contact with thorns in the scrubs. He was a timber-cruiser, making his

way back towards civilization. He had been on a tramp through 200 milts

of wild, comparatively unknown forest in this province, where there were

no trails, and where, water in the form of rushing river, deep lake, or

ugly muskeg was more common than dry land. He had been cut for several

weeks unaccompanied and, truth to relate, no one knew whether he was

alive or dead. He had been searching for fresh supplies for the sawmills

of his firm, and had wandered into as rough a corner of the country as

could be imagined on his quest. He had had to depend upon the game in

the forests and the fish in the rivers for sustenance over the greater

part of the journey, securing a little welcome variety when he struck a

settler’s homestead or a prospector's camp, which was seldom. He had

waded up to his waist through viscous slime, had swum wicked rivers and

creeks, and had made exasperating detours to round wide lakes, or had

built crude rafts to carry him from chore to shore. His sole guide had

been his compass. When he struck the fringe of the country he had

decided to pick up the railway about 200 miles south, had selected his

bearings, and had pushed ahead, keeping hits eyes wide open to take

stock of the timber on all sides. He had not spoken to a soul for nearly

a month when he tumbled into our camp, and his delight at being able to

snatch some conversation with a fellow white man may be better imagined

than described.

Throughout the remote

West and North-West the timber-cruiser is particularly active at the

presentment. The depletion of the known reserves of timber, and the

increasing demand for this commodity, especially for the manufacture of

paper, has drawn attention to the wilder and lesser known parts of the

Dominion, where the forests are known to be interminable, and hoarding

vast supplies of the most valuable woods of commerce. In the Upper

Fraser River valley, which as yet is wellnigh inaccessible, but which is

being penetrated by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, the gropes of the

most stately and valuable trees rise in unbroken seas from the banks of

the waterways to the heights of the mountains. On every hand, however, 1

saw evidences of the timber-cruiser’s activity. Here and there on the

steep mountain flank the prevailing expanse of deep green tone was

splashed by a white mark, where a tree had been felled, to bare a.

whitened stump indicating a timber limit that had been claimed and

possibly granted.

The cruiser in such

difficult country as this may make money rapidly. He may either proceed

out on his journey of discovery at a daily wage, varying according to

his ability from 20s. or more upwards; or he may arrange to scour the

country for a round sum, anticipating that the task will occupy so many

weeks. In the former case the incidental expenses, such as the

commissariat, the chartering of canoes and Indian guides will be

defrayed by those commissioning the enterprise, leaving the sum paid to

the timber-cruiser as a wage free from all deduction, except for what

private necessaries the bushranger may fancy. In the second instance the

cruiser will have to defray all such expenditure from the lump sum

allocated to him for the contract, and he generally contrives to pare it

down to the irreducible minimum, so that as wide a margin may be left to

himself as possible in the form of profit. A bulky pocket-book is

generally the only business impedimenta with which the bushranger

saddles himself, in which he makes copious field notes setting forth the

precise character of the timber investigated, its estimated yield per

acre, and other details which may be required. He will take stock of the

proximity of the reserves to a convenient means of getting the logs from

the forest to the site for a sawmill, selecting an advantageous and

strategical situation for water-driving. If he stakes an area of good

timber, he marks it off, roughly pacing distances, and indicating the

length and breadth of the claim upon a decapitated tree trunk, in much

the same manner as the settler selects and stakes his virgin land.

At times the task is

not to be lightly undertaken, and demand a man of infinite resource and

a robust constitution, who is not very easily lost in the trackless

wilds, and who, if he should get marooned in the ocean of timber, does

not lose his head, but can easily pick up his bearings and find his -nay

out again. The French-Canadian is a born timber-cruiser ; the forest is

his home. There was one of these bushrangers who had trekked to the

extreme West. I met him in the miring country fringing the Canadian

Pacific Railway. He could nose timber as easily as a cat can scent mice.

He had achieved a remarkable reputation for miles around, and was in

keen demand as being a son of the bush. There was never any apprehension

that he would come back from an expedition without very tangible fruits.

One firm suddenly found

themselves in dire need of further supplies of the raw material. In the

vicinity it was unobtainable. There was no alternative but to delve into

the forests farther afield. This cruiser was rounded up and the

situation explained. Haste was every consideration. When the principals

had described their requirements they asked the French Canadian when he

could start out.

“Right now,” was the

retort. “Give me a couple of men, and if you can fit me up with

provisions—well, all the better.”

“How long will you be

about it?”

“I’ll be back in six

weeks.”

“A thousand dollars if

you are,’ ’replied the principals, “end at the same time let us know the

best way to handle the lumber.”

Two hours later the

cruiser, with a couple of companions and a good stock of provisions,

pulled out of that township. The six weeks were almost up, and the

principals were worrying somewhat as to how things had progressed, as

they were nearing a tight comer commercially, when one afternoon in

strode the cruiser. He was considerably battered and dishevelled. He had

been having the toughest six weeks of his life, he stated, and if his

appearance -was any criterion, he certainly was not understating the

case. He had been struggling among the rocky slopes of the Selkirks, and

had succeeded beyond his own anticipations. He would have been back a

fortnight earlier, only he had been troubled by bush fires which

hindered his movements very appreciably. He dumped his rough notes of

the quality and character of the timber upon the table, together with a

crude though full statement of his suggestions for the sawmills. A steam

plant was required. As he had fulfilled his mission and was back on

time, he was handed the thousand dollars, which he pocketed with the

intimation that he “was going down to the hotel to get a drink, a square

meal, and a turn-in for a few hours to get some welcome sleep.”

He was aroused from his

slumbers the next morning early. The principals had considered his

notes, with his report., and wanted to see him immediately. He dressed

hurriedly, and was soon back in the office again. They were going to act

upon his instructions, would build a steam plant, but would he supervise

its erection and start it running? The cruiser was agreeable, on terms.

The firm undertook to ship all the material to the point as convenient

to the timber limit as possible, leaving him to contrive its removal

therefrom to the point of erection. They grasped the fact that the

latter part of the work was the most exacting, but they could not brook

the slightest delay. Again came the query, “How long will it take you?”

“If weather holds up,

I’ll have it started in a month from to-day.”

“Another thousand

dollars if you do, and. what’s more, we’ll give you a hundred dollars

for every day you can clip oft that month. Never mind about expense;

we'll attend to that. We want this mill started, and we have got to get

a move on.”

Off went the cruiser

once more. He left instructions as to where and how to ship the

requisite machinery, and with a gang of men he had soon regained the

forest and was cleaving a way through the scrub for the passage of the

bulky boiler and other cumbersome portions of the plant. He was bent

upon that thousand dollars, and as much premium as he could squeeze in,

so he urged his chums with good wages and an enticing bonus to let

themselves go. They went at it day and night. Getting up the boiler and

one or two ether details were exciting and exasperating, but three weeks

from the day the cruiser left the office for the second time the ripping

and buzzing of the circular saw was heard. He had got his thousand

dollars, and something like an additional seven hundred dollars into the

bargain.

It seems a wild manner

in which to do business, since that timber plant cost the round sum of

£2.000 by the time it was set going, of which the cruiser had pocketed a

comfortable £500 odd in the space of three months. But it paid the firm

hand over fist. The lumber commanded from £7 to £10 per thousand lineal

feet, and the mill, though turning out a rough 25.000 feet every day,

could not keep pace with the demand. True, these prices only lasted for

a short while, but in that brief period the owners recouped their

initial outlay comfortably two or three times over.

Many of the lumber

magnates of Canada have sprung from the humble lumber-jack. They gained

sufficient knowledge to enable them to start out as cruisers, and they

promptly went into the wilds and laid hands upon the finest stretches of

timber they could discover, filed their claims and either went off at

once to dispose of their acquisitions at a good price, or sat down and

waited for the day when prices would rise to flood level. There is one

stretch of first-class big timber standing on the Pacific coast to-day.

It was roped in by a long-headed timber-cruiser two or three decades

ago. He determined to hold on to it, and refused the most tempting

overtures for its purchase from the lumber princes. It is standing

unsold to this day, its value still appreciating by leaps and bounds

every year. It is difficult to say offhand what that holding is worth,

but it runs well into five figures.

The enterprising

timber-cruiser, although his operations are limited by more stringent

legislation, inasmuch as Canada has at last realized the significance of

its timber wealth, and is guarding its reserves with a more eagle eye

than formerly, has just as brilliant opportunities as were available

twenty-five years ago. There are certain woods for which almost a

fanciful demand prevails. Take cedar, for instance. The extent of known

and available stretches of this wood on the American continent at the

moment would not be sufficient, if bunched together, to make a

respectable forest fire. This dearth has hit the manufacturers of lead

pencils here. When the early inroads were made upon the cedar groves,

the wood was cut in the most wasteful manner. Now the industry would pay

twice or thrice as much as they gave for the primest wood when they

first set to work. The stumps which were left to rot are now being cut

up, and every square inch of good wood is being carefully cut out. In

Eastern Canada, when the pioneer settlers appeared on the scene, and set

to work to clear the land, the disrupted cedars were used to fashion

saddle fences To-day the fences are being tom down, the cedar fetching

fancy prices, and other cheaper woods, such as jack pine, are being made

to do duty for boundary purposes. On the Pacific seaboard, the discovery

of extensive stretches of hard woods will enable the

furniture-manufacturing industry to be set upon a firm footing in

Vancouver and other west coast cities. At the moment such an industry

cannot get a start, an there is no hard wood available for the industry,

except at prohibitive prices. The western coast has a heavy rainfall,

which is inimicable to the growth of hard woods; one and all are soft

and practically useless, except for timber-frame buildings, pulp-wood,

and the most common commercial uses.

Timber-cruising is not

without its need of excitement and adventure. The forest fire is the

greatest terror, and the bushranger is perforcedly exposed to its

perils, as he is compelled to penetrate the bush in his occupation. One

cruiser cherishes vivid memories of a narrow escape from being roasted

to death. It was way up in the mountains, and he had struck a fine patch

of healthy big timber. He was sitting down one evening in his small

A-tent -writing his notes, when a couple of Indians scuttled up. They

were highly excited, and on the run as he could see. A fierce forest

fire was waging and driving their way. The timber-cruiser had observed

the over-hanging cloud of blue smoke wreathing and combing about the

crags of the mountains, but had concluded that the actual scene of the

conflagration was miles and miles away. The Indians estimated that the

lint of fire was from ten to twelve miles in length. They hurried on.

and the cruiser, casting his eyes skywards and noting that there was

very little wind—what breeze there has had half an inclination to swing

round to blow the fire in the opposite direction and away from

him—concluded that he was safe enough for a time. He turned into bed

early, although he gave a somewhat anxious long look at the ruddy glow

overhead, and listened intently to the distant music of the flames.

In the night he woke

with a start. The wind was blowing half a gale, and he could hear the

tiding and falling roaring like rumbling artillery. He knew the meaning

of that sound only too well. He jumped out of his tent, and, to his

astonishment, the very heavens themselves appeared to be on fire. The

flames were on him. In a glance he took in the situation. There was only

one avenue for escape, for the fire was in a semicircle round him.

Without a moment’s hesitation, he grabbed his rifle and started off on

the run. discarding everything— even his precious notebook—as he saw

that his prospective timber limit was doomed. It was a mad headlong

flight for about two miles to the shores of a small lake nestling in the

depression of the mountains. He could feel the scorching lick of the

fire, and saw the angry fonguts darling hither and thither high above

his head amid a shower of sparks, as if a gigantic pyrotechnic display

were in progress. He gained the edge of the lake when the ruddy

devouring ring was no more than a mile behind him, jumped into the

water, and struck boldly out for a little islet. Gaining this refuge, he

crept under a jack-pine, and watched the fury of the fire and the

startled animals, who, driven by the implacable enemy, rushed pell-mell

into the water and struck out for the opposite shore. Ho watched the

Spruce-trees blow up with trepidation, and saw the blast created by the

raging flames snap off half trees and send them flying through the air,

burning as fiercely as petroleum-soaked torches.

These huge firebrands

rained into the lake on every aide, the hissing as the flames kissed the

water to be extinguished rivalling in volume the sputtering, cracking,

and roar of the forest in the throes of hellish agony. Ho dreaded one of

these torches dropping into his refuge, and setting it going to join in

the general disaster. If one did plump into the vegetation on the islet,

then he would have to make another hurried watery departure, as the

trees and bushes around him were being scorched as dry as tinder by the

heat of the fire on the mainland, barely a quarter of a mile distant.

For some six hours he sat there, cooped up under the sheltering tree,

shielding his face from the scorching heat, and striving to breathe

freely in a suffocating atmosphere. Then the fire, unable to proceed any

farther than the water’s edge, died out, leaving a smouldering.

blackened countryside as far as the eye could see in that direction, and

blotting out everything with a nauseating smoke. It was so hot that he

ventured to state that the temperature of the water in the lake had

“shot up twenty degrees.” Leastways, it felt like it to him as he swam

back once more to the scorched, charred shore, and picked his way

delicately over the glowing ashes, dodging falling trees and jumping

spurts of flame smouldering among the blotches of moss littering the

ground. That fire damped his timber-cruising ardour that season. The

castles he had been building in the air while writing his field notes

were just as visionary as when he first struck the country.

Yet the

timber-cruiser’s life is not to be despised. It is one means of making

money, and quickly, too, when the task is associated with a thick slice

of luck. |