|

ON entering the camp that

night my first inquiry was for "Frightens Him's" lodge. This was pointed out

to me, and in a moment I stood at the chief's door. The old man was there to

meet me, and I was welcomed most heartily. "Surely the Great Spirit has sent

you, John," was the manner of his greeting; "come into my lodge, behold it

is yours." I pulled my dogs out of their collars, left a message for some

one to pilot my men to where I was, and went in to be given the guest-seat

of honor.

"Sayaketmat," I said,

addressing the chief by his Cree name, "I am here on a mission. I have much

to say to the camps, and I wish you would send messengers to each one,

telling them that John wants to see the chiefs and head men assembled here

the day after to-morrow. Here is tobacco. Word your summons as you please,

but tell them that John brings greetings and messages and help, and fain

would see and speak with them two nights from now."

In a little while the runners

were away, and soon fifteen large camps would know of our arrival, for I

found that this was a big preconcerted rendezvous, and that within twenty

miles of where I sat in Sayaketmat's lodge there were gathered several

thousand Plain and Wood Crees, as well as a number of Saulteaux. The chief

soon let me know that evil counsel was predominating in these camps, but

said, "Who knows but that your visit at this time, coming as you have so

unexpectedly, and so welcome to some of us, will turn the whole tide of

feeling?" I very soon let him know what my programme was, and saw that it

met with his decided approval. In came my men, and we were domiciled in the

big lodge, and until midnight were stared at and interviewed by alternating

crowds who came and went as space allowed, and then, tired and worn with

nervous and physical strain, we slept until the camp stir awakened us on the

early Sabbath morning.

The site of the camp was on

an elevation several hundreds of feet above the surrounding country; at a

glance one could look across an expanse of from fifty to seventy-five miles

of country. A congregation of curious yet earnest listeners gathered for

service in the morning. It was a motley throng; all colors of paint, all

manner of costume, all sorts of men—murderers, horse thieves, warriors,

braves, chiefs and common men, polygamists and monogamists—a strange

mixture, but they behaved wondrously well while I did what I could in

directing their thought Godward. Twice I spoke in the big open, and held

several services in lodges, and thus the day passed while all looked forward

to the general gathering Monday morning. These before us were comparatively

known quantities; the most of them we had met before in divers places and

also in divers conditions; but tomorrow would come the strangers and wild

men who, reasonably or unreasonably, hated the white man and now charged up

to him all trouble and disease and hunger, made him the cause of many

deaths, said he was the evil genius, and were harboring a growing spirit of

revenge in their hearts. How would they receive me on the morning of the day

approaching? I can assure my reader I was a bit nervous that Sunday night,

but was so downright weary that I soon forgot everything in sound sleep,

after leaving the whole matter in the hands of my Heavenly Father.

Monday morning came bright,

cold and calm. I rose early and went out to view my surroundings. Young men

were starting for the distant caches of meat, and women striking out with

dogs and horses harnessed into travois for fresh supplies of wood. Scores of

women also were stretching and scraping robes and hides in the various

processes of preparing and dressing these, when suddenly, like a bolt out of

a clear sky, dark clouds gathered and burst, and a terrible storm was upon

us. In a lifetime on the frontier, and in countless storms, I do not

remember anything quite so sudden or severe as that blizzard which came to

us at the Hand Hills in February of 1871. I thought of the many from the

other camps who in all probability at my request were crossing the prairie

stretches to come to my meeting. In common with hundreds I thought of the

many who had gone forth for wood and meat and in search of horses, many of

whom were women and girls, and poorly clad at that, and my heart went down

in me for a time. I felt in a measure responsible for a lot of this

suffering and possible death, but here was the big storm making everything

hum about us and making every one work to keep lodges erect and fires going.

For six hours this sudden paroxysm of Nature's forces fumed and raged and

tore over our camp, and doubtless over a large area of country about us.

Tens of thousands of millions of sharply frozen moisture assailed us from

every point of the compass. Down went the temperature, and doubtless it was

this action of the Storm King that gave us, about three p.m., a clear sky

and the already guaranteed promise of from forty to fifty below zero for the

night quickly coming.

And now to the rescue! Out in

every direction issued parents and brothers and friends to seek their loved

ones. I fully expected many deaths, and if the people of this camp had not

been prepared by the centuries for the rigors of a northern clime many would

have perished. But these mothers and daughters and sons, the product of

generations of struggling with northern winters and endless plains, did the

best possible to be done under such circumstances, and either went with the

storm or lay quiet under it until the worst was spent. Thus the searchers

and rescuers found them, and by dark began to bring in the numb and frozen

and almost perished victims.

"John, come to my mother!"

"John, come to my sister!" "John, come to my son!" Come quick, John!" came

the appeal to me from all sides, and with a little cayenne pepper, the only

medicine I had, I went around from camp to camp helping to rub back to life,

administering a warm drink, dropping on my knees beside an unconscious

patient and offering a short prayer, which was a new evangel to the hearts

and ears of those who listened around the lodge fires that night. All the

while anxiety was heavy on me concerning the many probable victims of the

storm. About midnight there were arrivals from other camps, in twos and

threes and more, and I listened for the sound of mourning and wailing, and

was in great suspense as to the re- suit of my mission. It was a long, weary

night which preceded the morning of Tuesday, but morning finally came, and

was as if this world never knew a storm so far as sky and sun and landscape

glory were concerned.

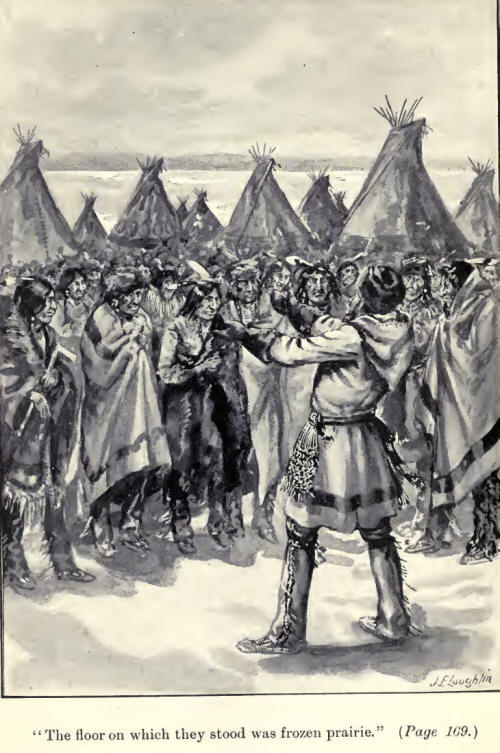

Again the crier went forth,

"Come to the centre of the camp! come and listen to John and in a short time

the large space was filling up. As I stood and looked into the many strange

faces before me, I could not help wondering how these wild, sullen,

disappointed and bereaved and ofttimes hungry men would receive my message.

I often think of the endurance of that audience. The floor on which they

stood was frozen prairie, with ice and snow for paint and varnish. The

temperature was down, I do not know where, for there was no thermometer

within two hundred miles of us. My breath became ice and hung as such upon

moustache and beard. I spoke for a full hour or more. I brought them the

greetings of the northern settlements; told them that both white and red men

were interested in them and sorrowed with them, and that my mission was to

tell them that we, like them, had suffered; that the anxiety about them had

resulted in my being sent by the Church and the great Company which had

dwelt amongst and traded with their people for many generations; that I did

not come empty-handed, or with lip sympathy merely, but I had with me

something for them to smoke, and also ammunition and flints and gun-worms

for their hunting and for protection from their enemies; that it was the

wish of all to help them. Great had been our mutual sorrow; doubtless we all

had sinned, and our Great Father had permitted this disease to come, and we

in common with many others were punished. As brave men it became us to

resignedly accept our punishment, and to repent of our past wrong-doing and

turn unto the great and good Spirit and live. I told them that we had not

been alone: that across the great waters a most fearful war had been going

on; that while we had lost hundreds by disease, over there tens of thousands

had been slaughtered. I gave them a picture of the siege of Paris, the

starvation and death and disease that accompanied it, and the terrible

slaughter of the Franco- Prussian battles, fresh on my brain from the papers

of the last packet. I wound up by saying, "I will gladly carry your messages

to those forts and settlements on the Saskatchewan, and when we are through

my men will distribute the gifts we have brought as the evidence of the

good-will and wishes of your old friends, the Hudson's Bay Company."

When I ceased speaking the

head chief present, Sweet Grass, rose, and addressing the assembly asked,

"Will I voice this multitude?" and there came back a thundering answer,

"Yes!" Then turning to me he said: "We are thankful that our friends in the

north have not forgotten us. In sorrow and in hunger and with many hardships

we have gathered here, where we have grass and timber, and, since we came,

buffalo in the distance, few, though still sufficient to keep us alive. We

have grumbled at hunger and disease and long travel through many storms and

cold; our hearts have been hard, and we have had bitter thoughts and

doubtless said many foolish and bad words, but it is true, as you say, John,

we have sinned, and we must bear our punishment. My people are thankful for

your coming to us; we are thankful that your father sent you, that the

Company chief asked you to come. We believe you, John; you belong to us,

therefore you were not afraid to come the long distance and enter as a

friend into our camp and lodges. Some of us have met you before; we have

listened to you because of what you said, but more because of the way you

have spoken even in our own language and as one of ourselves. Yes, John, all

these men and women and children from to-day are your friends, and as you

leave us we will think of you and wish you prosperity and blessing. Your

coming has done us good; it has stayed evil and turned our thoughts to

better things. We feel to-day we are not alone; man is numerous and God is

great. We are thankful for the gifts you have brought with you. We will

smoke and forget, and if there has been wrong will forgive. These women will

drink the tea, and bless the 'trading chief,' and bless John. Tell the

'trading chief' we thank him, and as in the past will again frequent his

forts and posts. Tell your father we thank him for his son and all his good

wishes for us and our people." Then, turning around in appeal to the crowd,

he asked, Have I spoken your minds ?" and again a great "Yes" came with loud

assent.

And. now we placed the people

in lines and circles, and my men and a few Indians I had selected went at

the work of distribution. Powder and balls and tobacco and tea and sugar and

gun-flints and gun-worms were given out, and never in my life did I witness

a more thankful and delighted crowd. Many a warm grip of the hand came to me

from men whom I had never previously seen. Little Pine, who had been quoted

as saying that he would kill my father the first chance he had, came to me

and said, "You have changed my heart, John; henceforth I will think good of

you and all your people." Ere long the last load of powder was given and the

last pipeful of tobacco carefully wrapped up or put away in the pouch of

some brave, and our present mission was done in this camp. I shouted to the

crowd: "We were five nights corning to see you, and, as you well know, we

travelled hard; but we know that your friends in the north are so anxious to

hear of you and to learn of your condition that my men and self will take

but three nights to reach Edmonton, when we will tell them of how we found

you, and will carry your kindly greetings to the 'trading chief' and in turn

to all the people of the north."

This was received with great

approval and shouts of "You can do it, John, if any one can."

It was late in the afternoon

when we left the rows and circles of lodges and took the trail leading over

the summit of the hills. We carried wood on our sleds and camped for a few

hours as night came on at the foot of the high range, and long before

daylight struck for the "north country." I remember well how my men handled

axes the next night "Now we will have a fire," was the frequent exclamation

from their lips.

Early Saturday afternoon we

were on the brink of the high bank of the noble Saskatchewan. It would seem

that some of the men were watching for and at once recognized us, for up

went the old flag and down the long hill we tobogganed after our eager dogs,

and across the ice and up the bank, to be met at the fort's gates by all the

inhabitants, at the head of them the Chief Factor and my father and

brother-in- law, Hardisty. The two latter had come up all the way from

'Victoria to watch for our coming, so anxious were they, as indeed were all

the settlements along the river. We were many times welcome, and when I had

opportunity to report there was much rejoicing. The dark spell was broken,

and we now looked into the future with hope for brighter days.

The grateful Chief Factor

took me into his office and told me that while he remained in charge of the

Saskatchewan district I should rank as an officer of the Company—that is, I

should have the entry of their forts and posts, be furnished with provisions

and even transports if I should need them, also be given a liberal discount

on any purchase I might make for family or self from any of their stores;

all of which was helpful to my work and gave me as a missionary and man in

the country a standing of respect and influence. Father was delighted with

the success of my mission, and Hardisty warmed to me more than ever.

Monday we started east and

reached Victoria Tuesday evening, and again resumed the routine duties of

our life. A trip to White Fish Like was undertaken, followed by several

trips to Indian camps, where from lodge to lodge we preached and lectured,

sowing the seeds of faith in God and man and country. Many an hour around

the camp-fire the eye glistened and the ear was tense, and the hearts of

strong men were moved, as in answer to some pertinent question we talked of

law and government and civilization and Christianity. No idle time was ours;

father was incessant, and if we had wished to loiter he would have none of

it. |